Back to Journals » Advances in Medical Education and Practice » Volume 14

The Primary Care Transformation Executive Fellowship to Develop Community Health Center Leaders

Authors Lewis JH, Appikatla S , Anderson E , Glaser K , Whisenant EB

Received 29 October 2022

Accepted for publication 17 January 2023

Published 12 February 2023 Volume 2023:14 Pages 123—136

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S395394

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Md Anwarul Azim Majumder

Joy H Lewis,1 Surekha Appikatla,1 Eboni Anderson,1 Kelli Glaser,2 Ebony B Whisenant1

1Department of Public Health, A.T. Still University School of Osteopathic Medicine in Arizona, Mesa, AZ, USA; 2Department of Primary Care, Rocky Vista University, Parker, CO, USA

Correspondence: Joy H Lewis, A.T. Still University-School of Osteopathic Medicine in Arizona, 5850 E. Still Circle, Mesa, AZ, 85206, USA, Tel +1 660 626 2121, Fax +1 480 389 3661, Email [email protected]

Introduction: Although many primary care providers from community health centers recognize health disparities and work to transform healthcare, skill gaps and limited support may hinder their ability to be change agents. The Primary Care Transformation Executive (PCTE) Fellowship at A.T. Still University School of Osteopathic Medicine in Arizona (ATSU-SOMA) seeks to address these barriers by providing professional development and support to primary care providers interested in leading change in the nation’s health centers.

Methods: The PCTE Fellowship is a structured, one-year interprofessional learning experience that emphasizes topics such as healthcare transformation, interprofessional practice, leadership development, and systems thinking. Quantitative and qualitative evaluation of the program was accomplished through surveys and semi-structured interviews throughout the fellowship.

Results: Feedback from 18 fellows showed perceived improvements in knowledge and skills related to the various curricular topics, increased engagement in leadership activities, and career advancement. Fellows developed practice and quality improvement projects and successfully implemented the projects within their health systems, addressing observed disparities.

Conclusion: Professional development and directed support for primary care providers can enhance their engagement in healthcare transformation and advance health equity.

Keywords: leadership, healthcare transformation, quadruple AIM, health systems science, social determinants of health, community health center, population health

Introduction

The A.T. Still University School of Osteopathic Medicine in Arizona (ATSU-SOMA) was established in 2007 with an innovative curricular model based on a unique partnership with the National Association of Community Health Centers (NACHC). Through the strong relationship with NACHC, ATSU-SOMA formed partnerships with member Community Health Centers (CHCs) across the United States, from New York to Hawaii. These health centers are community partner sites where ATSU-SOMA students become immersed in contextual learning environments. Students at ATSU-SOMA spend their first year on the Mesa, AZ campus and then travel to CHC communities for years 2–4 of their undergraduate medical education (UME). Students spend these years living, studying, and working in the CHC communities. This distributed model with early clinical training provides students with opportunities to become part of the CHC system and to study the social, economic, and medical needs of patients and communities.

ATSU-SOMA employs a variety of innovations to implement a fully accredited, decentralized curriculum. Embedding students within care delivery systems enables improved continuity-of-care, development of employment bonds, and deeply rooted local connections. ATSU-SOMA students develop an authentic perspective regarding the challenges patients experience when trying to access care (eg, linguistic, cultural, financial, geographic, etc.) and thus learn how to actively contribute to improving the health outcomes of vulnerable individuals and populations. With this innovative total immersion training program, ATSU-SOMA prepares physicians for the unique demands of working in America’s community health centers — the safety net for nearly 30 million patients, who receive care regardless of ability to pay.1,2

This unique medical education program provides an optimal support system for the development of an innovative, distributed, community health center based executive leadership program. Discussions with health center executives identified skill gaps and support needed to develop clinician-leaders who can further health center goals. These discussions combined with exploration of the literature and the team’s expertise provided the basis for fellowship development. The Primary Care Transformation Executive Fellowship empowers adult learners to be health care leaders equipped to inspire and drive a paradigm shift in the healthcare system. This United States Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) funded program is designed to train health center leaders to have the knowledge, skills, and attitudes required to affect health systems change. The program was designed so that post fellowship, the primary care champions would be equipped with enhanced leadership skills, a foundation in implementation science, the ability to conduct community oriented primary care projects, and the ability to address health disparities to meet the needs of vulnerable populations.

This paper describes the rationale for the development of a HRSA-funded Primary Care Transformation Executive Fellowship and outlines the methods used to implement the program. Further, it describes the innovative curriculum, evaluation measures and outcomes from the first four years of implementation.

Rationale and Development of Fellowship

Pervasive primary care workforce shortages stem from increasing numbers of retiring physicians, provider burnout, and a tendency for specialization over primary care for graduating medical students.3–7 The US is anticipated to have a shortage of anywhere from 17,800 to 48,000 primary care physicians by 2034.8 This trend will continue to affect patients and providers and can negatively impact individual and population health. Other health system stressors include an aging population, the COVID-19 pandemic, an ongoing opioid crisis, and the obesity epidemic.3,7,9,10 While these challenges impact all types of healthcare providers and health systems, Community Health Center providers feel the effects acutely. In 2020, Community Health Centers cared for nearly 30 million of the most vulnerable patients, regardless of their ability to pay.1,9,11 Health centers have had increasing difficulty attracting and retaining primary care providers.11,12 To meet the needs of the nation’s underserved, primary care provider recruitment and retention issues must be addressed. With a stable workforce, health center providers can focus on maintaining high-quality, comprehensive care with improved efficiency.13

Patients who have multiple or complex medical problems often receive higher-cost, uncoordinated care with little interprofessional collaboration.14 Studies show that comprehensive primary care reduces instances of illness and death and lowers health care costs.15 To provide this effectively, a paradigm shift will require systemic change that emphasizes cost control, value-based care, improved access, and attention to population health.14 A transformed system will proactively address social determinants of health and link payment to value. Transformed health care must be coordinated across providers and across settings. Successful transformation should be infused with evidence-based population health measures, reliably driven by data, and delivered by prepared providers performing at the top of their licenses in a manner consistent with their board certifications, using integrated and collaborative delivery models across the continuum. This process of leveraging health information can lead to shared decision making that encourages patient engagement and improved outcomes.16

Most critically, transformation requires effective leadership. True transformation addresses health systems and leads to cultural change in health care delivery and training that impacts vision, mission, and approaches to care.17 Effective leaders are needed to inspire and shepherd health center transformation.18–20 Effective health system leaders have the capacity to motivate and inspire change, often emphasizing collaboration and emotional intelligence. The type of leaders called for by the 2018–22 Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) Strategic Goals include individuals with business and financial acumen, evaluation skills, and clinical expertise along with a deep understanding of communication, relationships, and how to motivate, empower, and build a strong team.19,21 Leaders with these attributes are particularly important for health centers.

Many providers wish to lead reform efforts; however, skill gaps can prevent them from feeling empowered to do so.19 Providers are seldom trained in leadership, evaluation, education, or the nuances of a transformed health care system.18,19 Undergraduate and graduate medical education programs often rely on community-based practicing providers who serve as preceptors for students and residents. To develop transformation skills and implement change, these community-based preceptors need training in leadership and collaborative practice.18 Health center leaders trained in these areas can provide needed role-modeling and education for other community providers.

Health center leaders must have a great understanding of the systems in which they work and the pressures exerted on their patients and communities. Health Systems Science (HSS) has become the third pillar of undergraduate medical education. HSS adds a necessary dimension to basic and clinical science. Education in this field provides trainees and practicing providers the knowledge and skills needed to lead patient and systems-level improvements. This education covers areas such as high-value care, quality improvement, population health, informatics, and systems thinking.20,21 While primary care plays a vital role in our healthcare system, large-scale changes, particularly in health systems, are required to facilitate health care transformation.

The ATSU-SOMA undergraduate medical education program trains students at community health centers with the aim of developing the health center physician workforce for the future. Providing this pathway for health center providers is important. Training health center leaders to educate these students is also of critical importance.

The ATSU Primary Care Transformation Executive Fellowship was created to address Community Health Centers’ needs. A team from ATSU-SOMA collaborated with leaders from community health center partner sites and identified specific leadership training needs for their practicing providers. The team also outlined population health issues and areas for health systems improvements. With the support of health center leaders, the ATSU-SOMA team applied for funding to develop a one-year fellowship program to train community-based, practicing primary care physicians and physician assistants to champion healthcare transformation in community-based settings. The ATSU-SOMA health center partner sites were all offered an opportunity to participate in this project. The majority of the partner site entities either signed a pre-award memorandum of understanding or provided a letter of support for this program. The support from the clinical partner sites helped to demonstrate the need for the program and was key in helping to secure funding.

The program development and evaluation plans were submitted to the A.T. Still University, Arizona Institutional Review Board in August, 2018. The project was determined to be “non-jurisdiction” defined by the Codified Federal Regulations, 45 CFR 46 §46.102.

Methods

Recruitment and Outline of Responsibilities and Expectations

Upon notice of the project award, the team implemented a fellow selection process. Leaders from each partner site were sent a letter with details about the curriculum and support provided to fellows. They were offered the opportunity to submit fellowship candidates. Officers queried their clinicians, identified those with interest, and then chose one or two to recommend. Fellows were nominated by the health center officers and each candidate submitted a Curriculum Vitae and a personal statement describing their interest, goals and objectives for the fellowship. The team reviewed all applications and accepted fellows based on their experience, interests, and health center affiliation. A collaboration agreement with each partner site was developed to provide subawards to each health center sponsoring a fellow.

The collaborative agreements outlined the expectations that program Fellows be excused from clinical duty at least one day per month throughout the 1-year Fellowship. This time allowance was designed to ensure the ability of the fellow to participate in program activities and for the development of a local fellow-led health care transformation project to address a transformative need identified within the partnering site. The expectation was further outlined that each fellow would contribute personal time in addition to the protected time. The agreement detailed payments to each health center to partially cover this protected time. Fellows were not paid directly by the Fellowship and ATSU-SOMA did not charge the fellows or their health centers for the program.

In advance of program implementation, the ATSU-SOMA team communicated expectations with the leadership at each health center where the Fellows were employed. This ensured the Fellows would have regular access to their site’s organizational leaders and stakeholders for the thoughtful design of the Fellow-led health care transformation projects.

Annually, the health center partner sites were invited to submit candidates for program participation. With the overall goal of having 20 Fellows complete the program over five years, the aim was to recruit six Fellows in the first year, six in the second and then four each year thereafter. The program team also aimed for a distribution of sites to maximize geographic diversity and to ensure representation from rural and urban centers. Following the application and review process, the Fellows were chosen from the growing number of candidates.

Program Structure

The education format included a combination of weekly guided self-study materials delivered via a learning management system, monthly live virtual speakers and discussion sessions, and frequent 1:1 mentoring. Fellows spent an average of three hours per week on the independent learning activities and approximately four hours per month in the live virtual sessions. Virtual sessions engaged geographically diverse fellows in rich discussions. The curriculum was delivered using google classroom as the content platform. This allowed for ease of information sharing with fellows and communication during and after each fellow’s program year. The project team also employed google groups as a means of building long term networks for continued collaboration and discussion with fellowship completers. Videoconference technology was used to host monthly live sessions, which allowed fellows to hear from experts and to share their ideas in person despite the geographic diversity of the group. The multiple modes of communication helped fellows develop bonds and stronger networks. Because of our familiarity with distance learning, we were able to develop a purposefully distributed model and to adjust the program throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.

Fellowship Curriculum

The curriculum had two main elements. The first was content driven and framed around the health systems science competency domains developed by the American Medical Association.20 The second was the provision of education and support to develop, implement and evaluate a community oriented primary care transformation project.22,23 Within this framework, the curriculum emphasized: 1) population health, 2) health care transformation, 3) leadership skill development, and 4) interprofessional (IP) practice. Woven throughout the curriculum was an emphasis on identifying and addressing the social determinants of health and examining and addressing cultural bias. Fellows further developed their scientific writing and professional presentation skills through project outcomes dissemination.

The topics covered in the curriculum are detailed in Figure 1. Didactic content was distributed on a weekly basis by theme with each new skill building on the prior lessons. Textbooks related to health systems science and leadership development were utilized and woven into a variety of lessons. Program leaders created portions of the content designed to meet the needs of the fellows, with other content curated from a variety of articles, websites and videos. Reflection assignments allowed fellows to process and share what they learned.

|

Figure 1 Curricular Areas. The curriculum framework displays the major curricular areas in the center of the figure and topics covered around the outside. |

The fellows each developed, implemented and analyzed a community oriented primary care (COPC) transformation project. “COPC is a continuous process by which primary care is provided to a defined community on the basis of its assessed health needs through the planned integration of public health practice with the delivery of primary care services.”22 COPC involves using principles of public health, epidemiology, preventive medicine, and primary care to improve the health of a community. The ATSU-SOMA team has been teaching undergraduate medical students how to develop, implement and evaluate COPC projects for over ten years.23

Fellows worked in partnership with community members, health center leaders, and fellowship faculty to identify and address the needs of their community. Together, they worked to follow the steps of COPC; they defined the community of interest, identified health or other problems affecting this community, developed and implemented interventions, and conducted ongoing evaluations of the process and outcomes. Fellows were mentored and supported throughout all stages of their projects.

The ATSU team worked with each fellow and provided help with the tasks that are often difficult for practicing physicians and PAs to complete: protocol development, IRB applications, data analysis, abstract writing, scientific meeting submission and presentation development. The ATSU team worked with each fellow to ensure completion of required documents. The fellows were all closely involved with the conception and implementation of their plans. However, the fellowship team was able to take on administrative burdens to facilitate progress with each fellow’s project. The ATSU team communicated regularly with health center informatics personnel and engaged with each health center team for all project related data and informatics needs. This supported the fellows’ needs assessments and project designs by generating health center uniform data reports and other internal metrics. In addition, the informatics team coordination assisted with project implementation and evaluation. The fellows presented their completed projects to health center leaders and at local and national conferences.

Fellowship Program Evaluation

Evaluation of the PCTE Fellowship program included qualitative and quantitative assessments. The fellows’ perceptions regarding their knowledge and career development were assessed over the course of each year. Focus was placed on understanding the experiences of fellows in the program, and documenting the program outcomes over time.

The first evaluation was a Pre- and Post-Learner Needs Assessment. Each fellow completed a learner needs assessment that documented baseline perceived proficiency levels for curricular areas, including Myers-Briggs' personality types, leadership theory and styles, organizational behaviors, systems thinking, quality improvement, clinical decision support, workflow analysis, IP practice, lean management, quadruple aim, and community-oriented primary care. At the conclusion of the fellowship, fellows completed a post-learner assessment to measure perceived proficiency in the same curricular areas, yielding data and insights to inform the Project Team’s rapid continuous quality improvement.

The second evaluation was a mid-year assessment conducted through a semi-structured interview during the midpoint of the fellowship year. This assessment gathered information related to fellows’ opinions about the curriculum and experience with their transformation project plan.

The third evaluation was a semi-structured group interview conducted at the end of the fellowship year. This interview collected fellows’ feedback on all aspects of the fellowship including curriculum, live sessions, program structure and transformation projects. This also documented their opinions regarding how to improve the program and their perceptions regarding the benefits of participation in this fellowship. The assessment questions are depicted in Figure 2.

The final evaluation method was a Strength, Weakness, Opportunity, and Threat (SWOT) analysis done within the PCTE Team towards the end of each fellowship year. Figure 3 provides the questions used to guide the SWOT analysis discussion and future program planning.

|

Figure 3 SWOT analysis. The figure displays the questions used to guide the Strength, Weakness, Opportunity, and Threat (SWOT) analysis performed yearly for the duration of the PCTE fellowship. |

Data Analysis

The pre-and post-learners needs assessment data were compiled using Microsoft Excel and descriptive statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v28. The responses from the semi-structured interviews and SWOT analyses were compiled using Microsoft Excel. The data obtained from the semi-structured interviews and the SWOT analyses were analyzed using a thematic approach to qualitative analysis. The project team coded the responses, grouped them into broader themes, and summarized them. Two team members independently analyzed the themes and responses. Discussion followed and the full research team agreed with the designations.

Results

Enrollment and Participation

Twenty fellows were recruited and enrolled in the fellowship program from August 2018–2022. Of these, 18 completed the fellowship and two left the program due to other time commitments during the COVID-19 pandemic. The enrolled fellows comprised 15 MDs, two DOs, and three PAs who worked at federally qualified community health centers that provide care for vulnerable populations. All 18 of the fellows who completed the program belonged to the “most needed specialties” identified by NACHC (ie, Family Medicine, Pediatrics, Internal Medicine, and Psychiatry). Figure four displays a map with the community health center locations for the fellows who completed the program (Figure 4).

Program Assessments

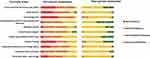

After completing the program most fellows’ perceived proficiency improved substantially in all categories. The pre-and post-learner needs assessments demonstrated fellows’ increased perceived abilities across each curricular area (Figure 5). The areas showing the most perceived improvement were: Interprofessional Practice Communication and Teamwork, Leadership Theories and Styles, Systems Thinking, and Community Oriented Primary Care.

Fellows reported satisfaction with the fellowship program content, delivery and format. Responses from the mid-year and end of fellowship semi-structured interviews are detailed in Table 1. These were grouped into the themes satisfaction with fellowship, experience with processes and professional growth.

|

Table 1 PCTE Fellowship - Mid-Year Assessment and End of Year Feedback from Four Cohorts of Fellows |

In both the mid-year and end of fellowship interviews, fellows reported they enjoyed all components of the program curriculum. The live sessions were reported to be the most valuable part of the fellowship. Fellows appreciated that these sessions allowed them the opportunity to connect with peers from other centers. Fellows expressed that they valued the education provided and particularly appreciated the Myers-Briggs Personality Types and Interprofessional Practice sessions. Fellows reported that the Harvard Clinical Leadership Program Webinars and Leadership Challenge textbook discussions were useful.

Fellows appreciated the diversity within the fellowship team, flexibility with the assignments, and support from the faculty and staff. Fellows appreciated learning how to approach problems and issues that arose related to their COPC projects. They mentioned challenges faced during the design and implementation of their projects and appreciated the support provided by the PCTE team.

Fellows reported that the fellowship helped them engage in difficult conversations and voice concerns in constructive ways. For some, this enhanced their self-confidence, and improved their perceived ability to influence senior leadership.

The fellows were at different experience levels along the continuum of leadership at the onset of their fellowship years. Post fellowship, ten of 18 fellows reported increased leadership responsibilities and career changing benefits. Six of the ten fellows who were in early stages of leadership careers reported that being part of the fellowship helped in the advancement of their career. They reported attaining a more senior role related to clinical care and additional teaching responsibilities. The fellowship helped reinforce the leadership skills of the remaining fellows, many of whom were Chief Medical officers, the highest clinical role within each community health center.

Yearly SWOT analyses completed by the PCTE team showed enrollment, curriculum, networking opportunities, and flexibility of the program and team, as the major strengths. The team identified the importance of increasing quantitative feedback. Difficulty with sustainability and lack of funding to continue the PCTE program after the grant period were identified as the biggest threats. Networking with other community health center providers and leaders, scientific meeting presentations and publishing academic work were seen as important opportunities.

COPC Projects

To date, 18 fellows completed community oriented primary care projects. These projects impact important primary care issues, address social determinants of health and address the needs of vulnerable populations. Fellows presented their COPC projects at 21 peer-reviewed local, regional, and national scientific meetings. A detailed list of project topics is presented in Table 2.

|

Table 2 Community Oriented Primary Care (COPC) Projects |

Discussion

Through its unique distributed model and partnership with community health centers across the nation, the ATSU-SOMA PCTE Fellowship was uniquely situated to address several areas of need including workforce development, health disparities, and interprofessional care coordination by training health care providers how to lead health center transformation. Highly qualified key personnel were appointed within the PCTE team to evaluate the program assessing quantitative and qualitative outcome measures. Evaluation has been, and continues to be, the cornerstone of this program. The PCTE team has evaluated the program by using an outcomes-focused approach, while providing appropriate flexibility in the evaluation process. The PCTE team used assessment and evaluation as an opportunity to acknowledge the lessons learned and to create a space for continuous improvement. Sharing the strengths and weaknesses of the program with other peer institutions at the HRSA Primary Care Training and Enhancement–Training Primary Care Champions (PCTE-TPCC) quarterly meetings kept the PCTE team accountable.

Program requirements have been met so far (after completion of year four of the program) with 18 graduated fellows in four years and outcomes of the program have been disseminated at several national conferences. The geographic diversity was one strength of the program impacting eight distinct communities around the US. Another unique feature of this program was the level of support provided to fellows. This included the curriculum that incorporated several methods and resources for learning, and also support for their transformation projects. Fellows appreciated the ongoing coaching from the PCTE team after fellowship completion and the availability of an ongoing learning network. Fellows reported they appreciated feeling taken care of on a personal and professional level, which is something that practicing health care providers often do not feel from employers.24 The fellows were appreciative of the diversity of the PCTE team and their peers, as they felt this added value to the program. Last, but certainly not least, the fellows reported that they would recommend this program to their colleagues.

Learning outcomes for PCTE program fellows demonstrated growth in knowledge and skill in several areas. Through pre-session assignments, live sessions, and self-reflection, as displayed in the learner pre- and post-assessments, the fellows observed improvement in their knowledge of healthcare transformation, health systems science, leadership theory, and interprofessional practice. They reported and demonstrated enhanced self-confidence to practice quality improvement through their development and implementation of quality improvement transformation projects. Through frequent data collection, results evaluation, and dissemination of the findings, the fellow’s participation in these transformation projects has helped inform best transformation practices for a diverse group of CHCs.

The program emphasizes the need for professional development and all 18 fellows from the first four cohorts have stayed connected with the PCTE team. They serve as Primary Care Champions and continue to be change agents in community-based primary care leadership initiatives. An additional downstream result of their work in this area was that the fellows reported increased comfort levels with writing and public speaking because of their involvement in a wide range of dissemination activities at local, state and national professional meetings and conferences. Fellows’ reported perceived advancement in their learning and that they felt the fellowship was a positive and valuable learning experience.

Implications

Programs, such as the HRSA grant-funded PCTE Fellowship, may help address the social determinants of health and can help health centers work towards lower health system costs, increased patient satisfaction, fewer hospitalizations, lower morbidity and mortality rates, and improved provider work experience.25 However, building strong primary care systems remains challenging.26 One of the goals of the PCTE program is to train primary care clinicians to not only lead healthcare transformation and become leaders within their communities, but to also apply the tools they gained from participating in the fellowship to reduce health disparities in their respective communities. While each project made a specific impact, the knowledge and skills the fellows developed over the course of this program will enable them to continue to drive positive changes for the patients and populations served by their community health centers.

More must be done to develop a sustainable primary care workforce. Of particular importance in achieving this goal is to develop and support primary care leaders. The professional development training provided by the PCTE program empowers leaders to provide community oriented primary care and enhances their clinical practice. Primary care clinicians enrolled in this fellowship relied on the PCTE team for continuous support and a well-rounded training experience. It is important to support this program and other health centers so similar support can be provided for developing leaders.

Limitations

The COVID-19 pandemic negatively impacted fellow retention; however, total enrollment and fellow completion goals were met. The program was funded by HRSA for five years, and the ATSU-SOMA team is working to determine if the program can be sustained without the HRSA funding. Given the time-intensive support provided to each fellow, no methods have been identified to sustain the program without external grant support. This program is unique and was built upon the foundation of the ATSU-SOMA network and partnership with community health centers. While this shows what can be accomplished through program development and support for fellows, the findings cannot be generalized to other primary care enhancement training programs.

Conclusion

The implementation of the ATSU-SOMA PCTE Fellowship Program has contributed to the development of primary care leaders at community health centers across the nation. By using a community-based health systems science approach to addressing health disparities, the fellows have worked towards providing equitable access to care through a population health lens. Further, the PCTE team has emphasized the importance of high-value care throughout their teachings and curriculum. This has been done by offering innovative solutions to improve efficiency and extending the program’s impact. The PCTE team’s ability to offer individualized support in the fellows’ conceptualization, design, implementation, and evaluation of their quality improvement projects has allowed each fellow to implement important health system changes while maintaining busy clinical practices. Fellows grew professionally, experienced career advancement, expressed improvement in their perceived proficiency in curricular areas and expressed feelings of empowerment and motivation for moving forward with future projects and leadership roles.

The lessons learned from this program illustrate the strengths and challenges of training primary care clinician leaders in a complex and rapidly evolving healthcare environment within the US. We found that individual mentorship and consistent communication with fellows enhanced their learning and personal growth. The processes employed in our fellowship included both group and individual meetings, with flexible scheduling to allow fellows to do the work of the program on their own time. This flexibility is particularly important for training programs with adult learners who have demanding jobs.

The individual mentorship and support also helped each fellow achieve success with their individual projects. The fellows’ transformation projects addressed a variety of important problems facing the communities they serve. While each project made a specific impact, the benefits from this program do not end with each project. The knowledge and skills the fellows developed over the course of this program will allow them to continue to drive positive changes for the patients and populations served by their community health centers. Overall, the program has advanced the work of building robust primary care systems at community health centers to address the social determinants of health for underserved and marginalized communities in targeted areas across the US.

Funding

This project was supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of an award totaling $1,999,650 with 0% percentage financed with nongovernmental sources. The contents are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by HRSA, HHS or the U.S. Government.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Heath Resorces & Services Administration. Health Center Program: Impact and Growth; 2020. Available from: https://bphc.hrsa.gov/about-health-centers/health-center-program-impact-growth.

2. National association of community health centers. Community Health Center Chartbook; 2022. Available from: https://www.nachc.org/research-and-data/research-fact-sheets-and-infographics/2021-community-health-center-chartbook/.

3. IHS Markit Ltd The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand 2016 Update: Projections from 2014 to 2025, final report. Washington, DC: AAMC; 2016.

4. Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD, Sinsky CA, et al. Burnout among health care professionals: a call to explore and address this underrecognized threat to safe, high-quality care. Discussion Paper. Washington, DC: Nat’l Academy of Medicine, NAM Perspectives; 2017.

5. Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple AIM: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):573–576. doi:10.1370/afm.1713

6. Shannon SC. Supporting clinician and medical student well-being. AACOM News; 2017.

7. Petterson SM, Liaw WR, Tran C, Bazemore AW. Estimating the residency expansion required to avoid projected primary care physician shortages by 2035. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(2):107–114. doi:10.1370/afm.1760

8. IHS Markit Ltd. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2019 to 2034. Washington, DC: AAMC; 2021.

9. Rosenbaum S, Paradise J, Markus A, et al. CHCs: Recent Growth and the Role of the ACA. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2017.

10. US Department of Health and Human Services. Opioid Abuse in the US and HHS Actions to Address Opioid-Drug Related Overdoses and Deaths. Washington DC: US Department of Health & Human Services; 2015.

11. National Association of Community Health Centers. Staffing the Safety Net: Building the Primary Care Workforce at America’s Health Centers. Bethesda, MD: National Association of Community Health Centers; 2016.

12. National Association of Community Health Centers. Community Health Center Workforce and Staffing Needs. Bethesda, MD: National Association of Community Health Centers; 2016.

13. PwC Health Research Institute. Top Health Industry Issues of 2018: A Year for Resilience Amid Uncertainty. New York, NY: PwC Health Research Institute; 2017.

14. HRSA/DHHS Advisory Committee on Training in Primary Care Medicine and Dentistry. Training Health Professionals in Community Settings During a Time of Transformation: Building and Learning in Integrated Systems of Care. Rockville, MD: HRSA/DHHS Advisory Committee on Training in Primary Care Medicine and Dentistry; 2014.

15. Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457–502. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x

16. CMS, Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation. State Innovation Models: Round Two, Initial Announcement for Funding Opp. # CMS-1G1-14-001. Woodlawn, MD: CMS, Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation; 2014.

17. Herring L. Lean experience in primary care. Qual Prim Care. 2009;12:271–275.

18. HRSA/HHS Advisory Committee on Interdisciplinary, Community-Based Linkages. Transforming IPE and Practice: Moving Learners from the Campus to the Community to Improve Population Health. Rockville, MD: HRSA/HHS Advisory Committee on Interdisciplinary, Community-Based Linkages; 2014.

19. American Hospital Association. Physician Leadership Education. Chicago, IL: American Hospital Association; 2014.

20. Skochelak SE, Hawkins RE, Lawson LE, Eds. AMA Education Consortium Health Systems Science. Elsevier; 2017.

21. Gonzalo JD, Chang A, Dekhtyar M, Starr SR, Holmboe E, Wolpaw DR. Health systems science in medical education: unifying the components to catalyze transformation. Acad Med. 2020;95(9):1362–1372. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003400

22. Mullan F, Epstein L. Community-oriented primary care: new relevance in a changing world. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(11):1748–1755. doi:10.2105/ajph.92.11.1748

23. Lewis JH, Whelihan K. Chapter 10: community health in action: the A.T. Still University’s school of osteopathic medicine in Arizona. In: Gonzalo JD, Hammoud MM, Schneider GW, editors. Value-Added Roles for Medical Students.

24. Sovold LE, Naslund JA, Kousoulis AA, et al. Prioritizing the mental health and well-being of healthcare workers: an urgent global public health priority. Front Public Health. 2021;9(679397). doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.679397

25. Bazemore A, Petterson S, Peterson LE, Bruno R, Chung Y, Phillips RL

26. O’Malley AS, Gourevitch R, Draper K, Bond A, Tirodkar MA. Overcoming challenges to teamwork in patient-centered medical homes: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(2):183–192. doi:10.1007/s11606-014-3065-9

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

Recommended articles

The Untapped Potential of the Quadruple Aim of Primary Care to Foster a Culture of Health

Rangachari P

International Journal of General Medicine 2023, 16:2237-2243

Published Date: 3 June 2023

Saudi Women’s Views on Healthcare Leadership in the Era of Saudi 2030 Health Transformation

Aldekhyyel RN, Alhumaid N, Alismail DS

Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare 2024, 17:237-249

Published Date: 16 January 2024

The Tensegrity Curriculum: A Comprehensive Curricular Structure Supporting Cultural Humility in Undergraduate Medical Education

Jones AC, Bertsch KN, Williams D, Channell MK

Advances in Medical Education and Practice 2024, 15:381-392

Published Date: 3 May 2024