Back to Journals » Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment » Volume 18

Psychological Disturbances and Their Association with Sleep Disturbance in Patients Admitted for Arrhythmia Diseases

Authors Hu LX, Tang M, Hua W, Ren XQ, Jia YH, Chu JM, Zhang JT, Liu XN

Received 9 April 2022

Accepted for publication 21 July 2022

Published 17 August 2022 Volume 2022:18 Pages 1739—1750

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S370128

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Yuping Ning

Li-xing Hu, Min Tang, Wei Hua, Xiao-qing Ren, Yu-he Jia, Jian-min Chu, Jing-tao Zhang, Xiao-ning Liu

Center of Arrhythmia, Fuwai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, 100037, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Xiao-ning Liu, Center of Arrhythmia, Fuwai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Peking Union Medical College, No. 167 North Lishi Road, Xicheng District, Beijing, 100037, People’s Republic of China, Tel/Fax +86 10 8839 6965, Email [email protected]

Objectives: This study aimed to assess the depression and anxiety status and their association with sleep disturbance among one single center Chinese inpatients with arrhythmia and help cardiologists better identify patients who need psychological care.

Methods: A cross-sectional survey was conducted among 495 inpatients with arrhythmia treated in Fuwai Hospital from October to December 2019. The psychological status and sleep quality were assessed using the Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS), the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). Multivariate logistic regression was used to identify the potential risk factors for anxiety and depression.

Results: The mean age of the participants was 52.8 ± 14.4 years, and 58.0% were male. Approximately 18.3% were in an anxious state, and 33.5% were in a depressive state. In multivariate logistic regression, age from 50 to 59 (p = 0.03), unemployment (p = 0.026) and sleep disturbance (p < 0.001) were the risk factors for anxiety status. Cardiac implanted electronic devices (CIEDs) (p = 0.004) and sleep disturbance (p < 0.001) were the risk factors for depression status. A total of 150 patients (30.3%) were categorized as having poor sleep quality (PSQI > 7). The adjusted odds ratio (OR) of having poor sleep quality was 4.30-fold higher in patients with both anxiety and depression (OR: 4.30; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.52– 7.35); 2.67-fold higher in patients with depression (OR: 2.67; 95% CI: 1.78– 4.00); and 3.94-fold higher in patients with anxiety (OR: 3.94; 95% CI: 2.41– 6.44).

Conclusions: Psychological intervention is critical for Chinese inpatients with arrhythmia, especially for patients aged 50– 59, unemployed, or those using CIEDs. Poor sleep quality could be an important risk factor linked to psychological disturbances.

Keywords: anxiety, depression, arrhythmia, sleep disturbance

Introduction

Arrhythmia is a common disease, and its incidence is increasing. Patients with arrhythmia often suffer from palpitations, chest tightness, and dizziness. Some types of arrhythmias can induce sudden cardiac death or seriously endanger human life and health.1 The pathogenesis of arrhythmia is very complex; treating abnormal rhythm only cannot solve the fundamental problem. The efficiency of existing treatments, including anti-arrhythmic drugs, is quite variable, and their scope is limited due to the adverse effects.2,3

Depression and anxiety are frequently encountered mental health problems associated with increased morbidity and mortality, greater financial burden, and reduced quality of life.4,5 According to studies based on the general population, insomnia was independently associated with the development of anxiety and depression.6,7 It is an exciting era in the field of behavioral cardiology as research that integrates the brain and the heart has opened new visions of investigation. Psychological factors may exhibit both substrate and triggering relationships with arrhythmia.8 Depression has been studied more frequently for its association with adverse endpoints such as sudden cardiac death.9 Patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) more often develop anxiety disorders, have a higher burden of depressive symptoms, and psychological functioning consistently predicts their symptoms and quality of life.10 Previous studies have shown that anxiety and depression symptoms can be used as predictors of future morbidity and mortality among patients with cardiac issues.11,12 Patients with severe mental disorders have a reduction in life expectancy by 10 years on average.13,14 Early evidence suggests that therapies aimed at decreasing the experience of negative emotion may decrease arrhythmia frequency in individuals with an anatomic substrate for atrial or ventricular arrhythmias.15 The Very Anxious Group Under Scrutiny study suggested that depression and anxiety may act via common pathways to increase the risk of arrhythmia, and that arrhythmia may explain the mortality risk associated with these factors in patients.16 Chronic sleep deprivation or fragmented sleep can increase cardiovascular events. If the sleep disorder persists for a long time, it will seriously affect the patient’s quality of life and effectiveness of treatment. Therefore, improving a patient’s psychological status may be a complementary strategy for arrhythmia treatment and a prospective way to reduce the related medical burden. Depression and anxiety are common mental health problems that are strongly associated with sleep disturbances, according to community-based researchers. However, this association has not been investigated among patients admitted for arrhythmia diseases.

Even with emerging evidence demonstrating associations between psychosocial factors and cardiac arrhythmias worldwide, few studies have demonstrated the psychological status of anxiety and depression associated with sleep disturbances among patients with arrhythmia in China, particularly in inpatients who required extra care. China is a populous country, and disease spectrums do not completely match those of populations abroad. Understanding the prevalence of anxiety and depression in Chinese patients not only provides guidance for the medical staff in China but also provides some reference for medical workers in other countries. Therefore, we conducted this cross-sectional study among inpatients with arrhythmia to assess their anxiety and depression status and their relationship with sleep disturbances to help cardiologists better identify patients who need psychological care. Depending on the results, we expect to provide preliminary data support for improving the comprehensive management of patients with arrhythmia and hope to improve the therapeutic effect of current arrhythmia treatments.

Materials and Methods

Patients

This cross-sectional study was conducted in the cardiovascular department of the Fuwai Hospital, a tertiary center in China, from October to December 2019. This was a convenience sample. The inclusion criteria were (a) inpatients diagnosed with an arrhythmia and (b) patients who were able to fluently read and write Chinese. The exclusion criteria were patients with problems of consciousness, cognition, vision, language, hearing, or understanding, or who were too severe or unable to complete the questionnaire survey or scale evaluation, or who disagreed to participate in the study, had a history of substance abuse and withdrawal, intoxication, medication abuse, or trauma. The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of the Fuwai Hospital, with an approval number of 2016–780. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. The work was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1989) of the World Medical Association.

Demographic features (age, gender, height, weight, marital status, and occupational status) and clinical features (complications, years having the disease, arrhythmia type) were systematically reviewed and recorded from the patients’ hospital charts and assessed by two cardiologists in face-to-face interviews. Marital status was classified as either currently having or not having a life partner, and occupational status was classified as either currently having or not having a job. All inpatients with arrhythmia diseases were divided into two subgroups based on their arrhythmia type: paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia, AF/atrial flutter without bradycardia, and premature ventricular contraction/ventricular tachycardia (VT) were merged into one large group as patients under radiofrequency catheter ablation (RFCA). Another group was patients who needed cardiac implanted electronic devices (CIEDs).

Measures

All participants were asked to complete self-report questionnaires, including the Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) to evaluate their anxiety and depression status. The SAS is a self-rating scale used to evaluate the subjective feelings of patients’ anxiety status and comprises 20 questions. Patients are rated as having anxiety with a score ≥50, and scores 50–59, 60–69, and 70+ indicate mild, moderate, and severe anxiety, respectively.17 The SDS is a self-rating scale used to evaluate the subjective feelings of patients’ depression status and comprises 20 questions. Similarly, scores are proportional to depression intensity, where scores ≥50 indicate depressed mood, and scores 50–59, 60–69, and 70+ indicate mild, moderate, and severe depression, respectively.18 Both SAS and SDS were proven to be reliable in the evaluation of anxiety and depression status in some inpatient groups.19 These scales are standard mental health assessment instruments, and the reliability and validity of the Chinese versions have been evaluated in a Chinese population.20,21

The sleep quality of all enrolled inpatients was assessed using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). The PSQI includes subjective sleep quality, sleep time, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep disorders, hypnotic drug use, and daytime dysfunction. It is used to evaluate the sleep status of patients in the past month. The scores of all aspects are added up to the total score. The higher the score, the worse the sleep quality. The reliability and validity of the Chinese versions have been evaluated in a Chinese population, and Translational version was validated in local language.22 The Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.84, the split half reliability of odd and even is 0.87, and the test–retest reliability of 2 weeks was 0.82. In this study, a total PSQI score of >7 was defined as indicating a sleep disorder or sleep disturbance or poor sleep quality.22 If the overall score is >7, the patients are shown to be suffering from a sleep disorder, and the higher the score is, the lower the sleep quality.23

Patients completed these questionnaires during their index hospitalization. They were measured and recorded by two trained psychologists. Data quality was assured by providing one week of training to data collectors and supervisors.

Statistical Analysis

All data analysis was performed using the statistical package SPSS™ Statistics, version 26 (IBM® SPSS™ Statistics, Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and nominal variables were presented as absolute and relative frequencies. The Student’s t-test and the Mann–Whitney U-test were used to compare the normally or non-normally distributed variables. The single-sample t-test was used to compare the score values of the arrhythmia sample with the general population. To explore factors associated with anxiety and depression, univariate analyses were assessed using the χ2 test or the t-test. Multivariate logistic regression was performed when p values of independent variables were ≤0.20 or clinically significant to prevent missing significant findings. As age and gender may have an influence on both dependent and independent variables, any variables that had univariate associations with p values ≤0.20 were adjusted for age and gender and also included. Differences were considered statistically significant at the 5% level (p < 0.05). Odds ratio (OR) estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are presented from the logistic regression analysis. Spearman’s correlation analysis was conducted to find the correlation relationship between anxiety and depression.

Results

Participant Characteristics

The study population consisted of 495 inpatients with arrhythmia. The mean age of the participants was 52.8 ± 14.4 years, 36.5% were over 60 years, and 58.0% were male. Moreover, 90.1% of the participants were married, 41.2% were unemployed, 43.0% had hypertension, 42.8% had hyperlipidemia, and 15.3% had diabetes mellitus. Over half of the patients were overweight or obese (64.4%). Just over half of the sample size had symptoms for <2 years (52.9%). The mean PSQI score was 6.2 ± 3.8, and 30.3% were in sleep disturbance. In addition, 99 patients (20%) had a CIED, and 396 (80%) patients were under RFCA. Table 1 presents sociodemographic variables, clinical factors, and comorbidities stratified by CIED and RFCA. Patients under CIED were more likely to be older, to have hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and coronary artery disease.

|

Table 1 Patients’ Characteristics (N=495) |

Overall Psychological Disturbances in Inpatients with Arrhythmia Diseases

Figure 1 displays the prevalence of anxiety and depression among different inpatients with arrhythmia.

|

Figure 1 The prevalence of different levels of anxiety and depression in different arrhythmia categories. |

According to the SAS, 18.3% were in an anxious state, including mild anxiety (13.7%), moderate anxiety (3.4%), and severe anxiety (1.2%). In the RFCA group, this was 13.6% (mild), 3.0% (moderate), and 1.0% (severe). In the CIED group, this was 14.1% (mild), 5.0% (moderate), and 2.0% (severe). The overall anxiety score was significantly higher (41.2 ± 9.4) than the Chinese norm (29.8 ± 10.5; t = 27.08, p < 0.001, Table 2).1

|

Table 2 Comparison of SAS and SDS Score Values Between Arrhythmia Inpatients and the Chinese Norm |

According to the SDS, 33.5% were in a depressive state, including mild depression (20.2%), moderate depression (12.1%), and severe depression (1.2%). In the RFCA group, this was 18.4% (mild), 11.4% (moderate), and 1.0% (severe). In the CIED group, this was 27.3% (mild), 15.1% (moderate), and 2.0% (severe). The overall depression score was much higher (44.1 ± 12.1) than the Chinese norm (33.5 ± 8.6), and a significant difference was observed (t = 34.38, p < 0.001, Table 2).2

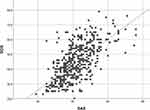

The comorbidity of anxiety and depression was 14.7% (RFCA 14.1%, CIED 17.2%), and having one condition was 37.2% (RFCA 34.3%, CIED 48.5%). According to Spearman’s correlation analysis, the SAS and SDS scores were correlated with each other (r = 0.675, p < 0.001, Figure 2).

|

Figure 2 Spearman’s correlation analysis self-rating anxiety scale scores and self-rating depression scale scores. Abbreviations: SDS, Self-Rating Depression Scale; SAS, Self-Rating Anxiety Scale. |

Associations of Demographic, Clinic Characteristics, and Arrhythmia Type with Anxiety and Depression

Results of univariate analysis are shown in Table 3. The potential independent variables with p ≤ 0.20 associated with anxiety or depression were selected for multivariable logistic regression. As we show special attention to the relationship between arrhythmia type and mental disorders, the arrhythmia subgroup was also selected for multivariable logistic regression. Previous studies showed that gender and social support might be related to mental disorders, so gender and occupational status were also selected for multivariable logistic regression.24,25

|

Table 3 Univariate Analysis of Patients’ Characteristics Associated with Anxiety and Depression |

As to anxiety status, 91 patients were included in the anxiety group and 404 in the non-anxiety group. There were significant differences in marital status (p = 0.03), occupational status (p = 0.01) and sleep disturbance (p < 0.001), but there was no significant difference in arrhythmia types according to univariate analysis. In multivariate logistic regression, age from 50 to 59 (p = 0.03), unemployment (p = 0.026), and sleep disturbance (p < 0.001) were the risk factors for anxiety status (Table 4).

|

Table 4 Multivariable Regression of Patient Characteristics Associated with Anxiety, Depression and Sleep Disorder |

In terms of depression status, 166 patients were included in the depression group and 329 in the non-depression group. There were significant differences in arrhythmia type (p = 0.01), gender (p = 0.002), marital status (p = 0.046), and sleep disturbance (p < 0.001) according to univariate analysis. In multivariate logistic regression, CIED (p = 0.004) and sleep disturbance (p < 0.001) were the risk factors for depression status (Table 4). The depression rate was higher among patients with CIED as compared with those under RFCA (44.4% vs 30.8%, χ2 = 6.61, p = 0.01).

The Relationship Between Psychological Disturbances and Sleep Disturbances

We then analyzed the relationship between psychological disturbances and sleep disturbances. This showed 150 patients (30.3%) were categorized as having a poor sleep quality (PSQI >7). Many insomniacs (46.7% or 70/150) did not have a comorbid mood disorder, a significant proportion (37% or 53/144) had a comorbid anxiety disorder, and a few had a comorbid mood disorder (26.7% or 40/150). Of all participants with an anxiety disorder (n = 90), a majority also had insomnia (53.3% or 48/90); by level of anxiety, this was mild (47.8% or 32/67), moderate (64.7% or 11/17), and severe (83.3% or 5/6). Of all participants with a depression disorder (n = 165), a majority also had insomnia (43.7% or 72/165); by level of depression, this was mild (45% or 45/100), moderate (40.7% or 25/59), and severe (50% or 3/6). However, we observed a moderately positive correlation between PSQI and SAS score for anxiety (r = 0.31, p < 0.001) and SDS score for depression (r = 0.31, p < 0.001).

Based on the presence of anxiety and depression, we created another two groups; there were 311 patients (62.8%) who had neither depression nor anxiety, and 73 (14.7%) who had both. The prevalence of poor sleep quality was 22.5% and 55.6%, respectively. The adjusted OR of having poor sleep quality was 4.30-fold higher in patients with both anxiety and depression (OR: 4.30; 95% CI: 2.52–7.35). The adjusted OR of having poor sleep quality was 2.67-fold higher in patients with depression (OR: 2.67; 95% CI: 1.78–4.00). The adjusted OR of having poor sleep quality was 3.94-fold higher in patients with anxiety (OR: 3.94; 95% CI: 2.41–6.44) (Table 5).

|

Table 5 The Frequency of Poor Sleep Quality in Patients Without Psychological Disturbances (None) and Those with Depression Alone, Anxiety Alone, and Both |

Discussion

Our study aimed at exploring anxiety and depression status and the related risk factors in Chinese inpatients with arrhythmia. The results showed that the prevalence of anxiety and depression were more common in inpatients with arrhythmia in China than the Chinese norm; about 18.3% were in an anxious state, and 33.4% were in a depressive state. Age 50–59 and unemployment seemed to be the risk factors for anxiety, and CIED seemed to be a risk factor for depression. These patients should be given more psychological care.

It should be noted that, in general, depression and anxiety are highly comorbid; there is evidence that half to two-thirds of adults with anxiety also suffer from depression.26 Twin and family studies suggest that their comorbidity is largely explained by shared genetic risks.27 Consistently, recent genome-wide association studies have showed a high genetic correlation (rG: 0.75–0.80) among people with anxiety disorders, major depressive disorder, and neuroticism,28,29 which supports the existence of a general genetic risk factor that could explain their high rate of co-occurrence. As regards pathophysiology mechanisms, it is well established that anxiety and depressive disorders share some risk factors, such as heightened stress responsivity.30

Despite the differences in methodologies, most published studies indicate some type of indistinct relationship between arrhythmia and mental disorders. Polikandrioti et al surveyed permanent AF; approximately 34.9% of the patients had high levels of anxiety, and 20.2% had high levels of depression.24 Implanted cardiac defibrillator (ICD) treatment was found to be closely related to anxiety and depression. In Bilge et al’s study, 46% had anxiety, and 41% had depression.31,32 According to prospective cohort studies, psychological factors, such as depression and anxiety, significantly increased the vulnerability of VT in patients with heart problems.15

From previous studies, elderly patients with AF and those with ICD were more likely to suffer from depression or anxiety.24,33 This is partially because of physical impairment, unhealthy lifestyle, poor treatment adherence,35 or cognitive impairment in those patients.36 Conversely, in our study, patients aged 50–59 years were more likely to suffer from anxiety. One explanation is that our patients between the ages of 50–59 were just retired or about to retire, which may increase anxious feelings as they adapt to various changes in lifestyle and roles.

Our study showed that unemployed patients were more likely to be anxious. Occupational status is one aspect of socioeconomic status. In cardiovascular disease, socioeconomic status is an important predictor.37 Perpetual low social status was associated with a two-fold increase in cardiovascular mortality.38 Data from the Swedish Longitudinal Occupational Survey of Health study showed that job strain was a highly significant predictor of AF (OR: 1.93) when the exposure time was more than 10 years.39 There was evidence in a cardiovascular disease study that objective or subjective lack of social support was associated with a higher risk of developing cardiovascular diseases and a higher risk of mortality,40 so it should be reasonable that enhancing social support for patients with arrhythmia diseases could at least partially improve their prognosis. Therefore, it is necessary that medical staff pay more attention to unemployed patients. Also, it might be a good choice for government and social workers to provide jobs for suitable patients to reduce the burden of anxiety in patients with arrhythmia.

Data also revealed that gender had no relationship with mental health disorders. However, gender-specific factors are found in congestive heart failure, which manifests more frequently as tiredness and exhaustion in women41 and, in turn, can be misinterpreted as depression. Dabrowski’s study also showed a significant association between women and depression in patients with AF.42 The female preponderance to depression was partially explained by the well-documented gender differences in the pattern and outcomes of cardiac disease ranging from genetic factors to differences in daily living or health behaviors, delays in responding to symptoms, and several other factors.43

Likewise, we noted no relationship between mental health disorders and marital status. Polikandrioti et al surveyed AF and found marital status had no relationship with either anxiety or depression.24 Wong et al also found no relationship between marital status and mental health disorders among patients with ICD.33 Wong reported that married patients with ICD tend to be less depressed. In theory, marriage is a resilient factor because the spouse may provide physical, emotional, and social support to help patients cope with difficulties in their daily activities.33 However, the rate of individuals being alone in our study was too low, so the bias couldn’t be neglected. Additionally, cultural differences may be another reason for these findings. In China, married people undertook more responsibilities for their family, and they were afraid of increasing the burden for family members.

In this study, we found that inpatients with arrhythmia, especially patients with CIEDs, had a higher prevalence of depression. This may be partially explained by the age difference between the CIED and RFCA groups. However, depression had no significant correlation with age in our study. Patients under CIED were more likely to suffer from hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and coronary artery disease, while none of them were risk factors for depression. From a pathophysiological perspective, comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidaemia and systemic inflammation as well as age and multiple stressors may impact on both cardiac and mental health conditions, and genetic or epigenetic mechanisms may affect the heart and brain in a comparable fashion.34 A frequently postulated mechanism relating the risk of arrhythmia to psychological distress is cardiac autonomic dysfunction, so the autonomic system imbalance may play an important role.8

Sleep disturbances involve the genesis and perpetuation of anxiety and depression.44 In this study, we investigated patients with arrhythmia to confirm the association between poor sleep and the risk of depression or anxiety. We show, for the first time, that a comorbidity of poor sleep increased the risk of depression in patients with a chief complaint of headache (OR: 2.907) than without, as well as an increased risk for an anxiety disorder (OR: 2.661). These results suggest that cardiologists should pay close attention to sleep problems and evaluate their patients early for proper treatment. Of course, the relationship between sleep and anxiety is complex, and some studies suggest that anxiety and depression may also contribute to sleep disorders. Thus, the relationship between sleep and anxiety may be bidirectional.45

In this study, anxiety and depression were comorbid, and both were the risk factor for each other. This can be considered as an argument to support the hypothesis that these two symptoms share common pathophysiological mechanisms. However, depression can be present in the absence of anxiety and vice versa, except for some general factors related to oxidative stress and inflammation.

There were several limitations to this study. The studied population was in a single medical center under one evaluation, and the convenience sample restricted the generalization of study findings on all the patients with arrhythmia diseases. Some potential correlation factors, such as education level and income level, were unavailable. This study did not focus on these patients’ quality of life, which limited the clinical value and application. And there is no objective index to evaluate the sleep status of all patients. Also, it should be stressed that the relationship between depression, anxiety, and arrhythmia is complicated. In the future, more studies will need to be implemented to focus on these aspects.

Despite these limitations, our study is novel as we systematically investigated the profiles of patients with arrhythmia, depression, and anxiety. It should be stressed that the relation between depression, anxiety, and arrhythmia is complicated. Although in our study the results showed that the prevalence of anxiety and depression were more common in inpatients with arrhythmia in China than the Chinese norm, it is still unclear whether depression contributes to arrhythmia or vice versa. Our results will provide a useful reference for further longitudinal studies of arrhythmia attributed to a psychiatric disorder or psychiatric comorbidity of arrhythmia. This study will raise the awareness of cardiologists to identify the pathogenesis of arrhythmia overlapping with depression or anxiety and facilitate appropriate treatments or referral for psychological care. Whether or not remedies implicated in the treatment of patients with anxiety/depression might deteriorate the arrhythmia status of the patients - or are safe to use is still obscure. We hope that more cohort studies with large populations will focus on this issue in the future.

Conclusion

This study indicates that anxiety and depression are widely spread among inpatients with arrhythmia in China. Age from 50 to 59 and unemployment were positively associated with anxiety. Patients with CIEDs were more likely to suffer from depression as compared with patients under RFCA. Therefore, the identification and treatment of co-occurring psychological disorders in those patients, especially for those who are unemployed, aged 50–59, or with CIEDs, are urgent in China. Future studies with chronological designs investigating the progression of mental health symptoms post-treatment of arrhythmia and their predictors and experimental studies targeting treatment approaches are encouraged.

Ethics approval

This study was conducted with approval from the Ethics Committee of Fuwai Hospital (2016-780). This study was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 6152 7811 and U1913210).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in relation to this work.

References

1. Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2020 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141(9):e139–e596. doi:10.1161/cir.0000000000000757

2. AFFIRM First Antiarrhythmic Drug Substudy Investigators. Maintenance of sinus rhythm in patients with atrial fibrillation: an affirm substudy of the first antiarrhythmic drug. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(1):20–29. doi:10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00559-x

3. Torp-Pedersen C, Møller M, Bloch-Thomsen PE, et al. Dofetilide in patients with congestive heart failure and left ventricular dysfunction. Danish investigations of arrhythmia and mortality on dofetilide study group. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(12):857–865. doi:10.1056/nejm199909163411201

4. Vos T, Allen C, Arora M. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1545–1602. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31678-6

5. Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Wittchen HU. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012;21(3):169–184. doi:10.1002/mpr.1359

6. Jaussent I, Bouyer J, Ancelin ML, et al. Insomnia and daytime sleepiness are risk factors for depressive symptoms in the elderly. Sleep. 2011;34(8):1103–1110. doi:10.5665/sleep.1170

7. Neckelmann D, Mykletun A, Dahl AA. Chronic insomnia as a risk factor for developing anxiety and depression. Sleep. 2007;30(7):873–880. doi:10.1093/sleep/30.7.873

8. Peacock J, Whang W. Psychological distress and arrhythmia: risk prediction and potential modifiers. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;55(6):582–589. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2013.03.001

9. Rea TD, Eisenberg MS, Sinibaldi G, White RD. Incidence of ems-treated out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in the United States. Resuscitation. 2004;63(1):17–25. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2004.03.025

10. Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, et al. 2020 Esc guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (Eacts): the task force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (Esc) developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (Ehra) of the Esc. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(5):373–498. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa612

11. Kikkenborg Berg S, Caspar Thygesen L, Hastrup Svendsen J, Vinggaard Christensen A, Zwisler AD. Anxiety predicts mortality in icd patients: results from the cross-sectional national copenhearticd survey with register follow-up. PACE. 2014;37(12):1641–1650. doi:10.1111/pace.12590

12. Berg SK, Thorup CB, Borregaard B, et al. Patient-reported outcomes are independent predictors of one-year mortality and cardiac events across cardiac diagnoses: findings from the national denheart survey. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2019;26(6):625–637. doi:10.1177/2047487318769766

13. Wahlbeck K, Westman J, Nordentoft M, Gissler M, Laursen TM. Outcomes of Nordic mental health systems: life expectancy of patients with mental disorders. Br j Psych. 2011;199(6):453–458. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.110.085100

14. Gale CR, Batty GD, Osborn DP, Tynelius P, Rasmussen F. Mental disorders across the adult life course and future coronary heart disease: evidence for general susceptibility. Circulation. 2014;129(2):186–193. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.113.002065

15. Lampert R. Behavioral influences on cardiac arrhythmias. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2016;26(1):68–77. doi:10.1016/j.tcm.2015.04.008

16. Watkins LL, Blumenthal JA, Davidson JR, Babyak MA, McCants CB

17. Zung WW. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics. 1971;12(6):371–379. doi:10.1016/s0033-3182(71)71479-0

18. Zung WW, Richards CB, Short MJ. Self-rating depression scale in an outpatient clinic. Further validation of the Sds. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;13(6):508–515. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1965.01730060026004

19. Tian J, Li L, Tao CL, et al. A glimpse into the psychological status of E.N.T inpatients in China: a cross-sectional survey of three hospitals in different regions. World J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;5(2):95–104. doi:10.1016/j.wjorl.2018.11.002

20. Tao M. The revised self rating anxiety scale (Sascr) the reliability and validity. Chin J Neuropsyc Dis. 1994;4:e34.

21. Peng H, Zhang Y, Ji Y, et al. Reliability and validity analysis of Chinese version of self-rated depression scale for women in rural areas. Shanghai Med Pharm J. 2013;14:20–22. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1006-1533.2013.14.011

22. Liu XC, Tang MQ, Hu L, et al. Reliability and validity of Pittsburgh sleep quality index. Chinese J Psych. 1996;29(2):103–107.

23. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF

24. Polikandrioti M, Koutelekos I, Vasilopoulos G, et al. Anxiety and depression in patients with permanent atrial fibrillation: prevalence and associated factors. Cardiol Res Pract. 2018;2018:7408129. doi:10.1155/2018/7408129

25. Thrall G, Lip GY, Carroll D, Lane D. Depression, anxiety, and quality of life in patients with atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2007;132(4):1259–1264. doi:10.1378/chest.07-0036

26. Lamers F, van Oppen P, Comijs HC, et al. Comorbidity patterns of anxiety and depressive disorders in a large cohort study: the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (Nesda). J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(3):341–348. doi:10.4088/JCP.10m06176blu

27. Middeldorp CM, Cath DC, Van Dyck R, Boomsma DI. The co-morbidity of anxiety and depression in the perspective of genetic epidemiology. A review of twin and family studies. Psychol Med. 2005;35(5):611–625. doi:10.1017/s003329170400412x

28. Forstner AJ, Awasthi S, Wolf C, et al. Genome-wide association study of panic disorder reveals genetic overlap with neuroticism and depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26(8):4179–4190. doi:10.1038/s41380-019-0590-2

29. Nagel M, Jansen PR, Stringer S, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies for neuroticism in 449,484 individuals identifies novel genetic loci and pathways. Nat Genet. 2018;50(7):920–927. doi:10.1038/s41588-018-0151-7

30. Janiri D, Moser DA, Doucet GE, et al. Shared neural phenotypes for mood and anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis of 226 task-related functional imaging studies. JAMA psychiatry. 2020;77(2):172–179. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3351

31. Bilge AK, Ozben B, Demircan S, Cinar M, Yilmaz E, Adalet K. Depression and anxiety status of patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillator and precipitating factors. PACE. 2006;29(6):619–626. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8159.2006.00409.x

32. Amiaz R, Asher E, Rozen G, Czerniak E, Glikson M, Weiser M. Do implantable cardioverter defibrillators contribute to new depression or anxiety symptoms? A retrospective study. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2016;20(2):101–105. doi:10.3109/13651501.2016.1161055

33. Wong MF. Factors associated with anxiety and depression among patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillator. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(9–10):1328–1337. doi:10.1111/jocn.13637

34. Schnabel RB, Hasenfuß G, Buchmann S, et al. Heart and brain interactions: pathophysiology and management of cardio-psycho-neurological disorders. Herz. 2021;46(2):138–149. doi:10.1007/s00059-021-05022-5

35. Chatap G, Giraud K, Vincent JP. Atrial fibrillation in the elderly: facts and management. Drugs Aging. 2002;19(11):819–846. doi:10.2165/00002512-200219110-00002

36. Wozakowska-Kapłon B, Opolski G, Kosior D, Jaskulska-Niedziela E, Maroszyńska-Dmoch E, Włosowicz M. Cognitive disorders in elderly patients with permanent atrial fibrillation. Kardiol Pol. 2009;67(5):487–493.

37. Tang KL, Rashid R, Godley J, Ghali WA. Association between subjective social status and cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular risk factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;6(3):e010137. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010137

38. Stringhini S, Zaninotto P, Kumari M, Kivimäki M, Lassale C, Batty GD. Socio-economic trajectories and cardiovascular disease mortality in older people: the English longitudinal study of ageing. Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(1):36–46. doi:10.1093/ije/dyx106

39. Fransson EI, Nordin M, Magnusson Hanson LL, Westerlund H. Job strain and atrial fibrillation - results from the Swedish longitudinal occupational survey of health and meta-analysis of three studies. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2018;25(11):1142–1149. doi:10.1177/2047487318777387

40. Valtorta NK, Kanaan M, Gilbody S, Ronzi S, Hanratty B. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart. 2016;102(13):1009–1016. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308790

41. Regitz-Zagrosek V, Seeland U. Sex and gender differences in myocardial hypertrophy and heart failure. Wiener medizinische Wochenschrift. 2011;161(5–6):109–116. doi:10.1007/s10354-011-0892-8

42. Dąbrowski R, Smolis-Bąk E, Kowalik I, Kazimierska B, Wójcicka M, Szwed H. Quality of life and depression in patients with different patterns of atrial fibrillation. Kardiol Pol. 2010;68(10):1133–1139.

43. Ball J, Carrington MJ, Wood KA, Stewart S. Women versus men with chronic atrial fibrillation: insights from the standard versus atrial fibrillation specific management study (Safety). PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e65795. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0065795

44. Castro MM, Daltro C. Sleep patterns and symptoms of anxiety and depression in patients with chronic pain. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2009;67(1):25–28. doi:10.1590/s0004-282x2009000100007

45. Alvaro PK, Roberts RM, Harris JK. A systematic review assessing bidirectionality between sleep disturbances, anxiety, and depression. Sleep. 2013;36(7):1059–1068. doi:10.5665/sleep.2810

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.