Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

Towards the Contributing Factors for the Inconsistency Between English as a Foreign Language (EFL) Teachers’ Equity-Oriented Cognition and Practices

Authors Chen F , Abdullah R

Received 3 March 2023

Accepted for publication 28 April 2023

Published 3 May 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 1631—1646

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S409680

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Mei-Chun Cheung

Feifei Chen,1,2 Rohaya Abdullah2

1Department of College English, Zhejiang Yuexiu University, Shaoxing, Zhejiang, People’s Republic of China; 2School of Educational Studies, Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM), Penang, Malaysia

Correspondence: Feifei Chen, Zhejiang Yuexiu University, Shaoxing, Zhejiang, People’s Republic of China, Tel +8013957567140, Email [email protected]

Backgrounds and Aims: Though EFL teachers now generally hold an equity-oriented mindset, they are often blamed for not implementing equitable practices in the actual teaching. The contributing factors causing cognition-practice inconsistency should be recognized and highlighted to ensure equitable teaching. Therefore, by taking an interpretative qualitative approach, this study explored in-depth the contributing factors that caused the mismatch between EFL teachers’ equity-oriented cognition and practices.

Methods: We adopted classroom observation and stimulated recall interviews with 10 university teachers to examine the contributing factors that lead to cognition-practice inconsistency.

Results: Our results showed two experiential factors (unpleasant schooling experiences and limited effective training) and five contextual factors (unfavorable student factors, inharmonious classroom climate, toxic school contexts, equity-deficient education system, and negative social cultures) mediated the relationship between teachers’ equity-oriented cognition and practices.

Conclusion: The findings shed light on an association between influential factors and teachers’ equity-oriented cognition-practice mismatch. Moreover, an equity-oriented teaching framework was thus proposed to help eliminate the constraining effect of these factors.

Keywords: educational equity, English as a Foreign Language, EFL, contributing factors, cognition-practice inconsistency

Introduction

Educational equity, as a mandate in Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4), has long been a major subject on the global agenda in the 21st century.1,2 As OECD defines, educational equity contains two dimensions, fairness and inclusion.3 Being compulsory in many non-English-speaking nations, English language teaching is seen as a primary communication medium in the global educational space.4 In the context of prioritizing equity and excellence in education, as scholars5,6 argue, English as a Foreign Language (EFL) teaching is strongly tied to the equity goal and thus exerts a substantial impact on the grand course of closing educational and social disparities. Therefore, primacy should be given to achieve equity in EFL teaching by creating a fair and inclusive learning environment where equal learning opportunities for all can be provided and diversified needs of students from different backgrounds can be fulfilled.7–9

To reach the grand aim of enhancing equity in the educational arena, the role teachers play in the actual classroom has been recognized and highlighted.10–12 As a moral and political undertaking, equity can be effectively achieved through teachers’ equitable classroom teaching13 since teachers play a crucial role in students’ lives and even can be a deciding factor for students’ success. Equitable teaching should adhere to the principles of fairness and inclusion, and this can be achieved by implementing strategies at three levels: instructional, cognitive, and affective. To ensure educational equity, teachers should use instructional strategies such as incorporating diverse learning materials14,15 and providing opportunities for collaboration and hands-on activities.16,17 Cognitive strategies, such as encouraging diverse perspectives from students18,19 and promoting critical thinking skills among students20 are recommended. Additionally, at the affective level, it is advised that teachers should demonstrate cultural sensitivity and responsiveness21 and show care and love for every student.22,23 As supported by empirical data from multiple studies,24,25 teachers’ equity-oriented pedagogical practices do largely influence students’ learning behavior and psychological engagement, facilitating learners to be intellectually, socially, and psychologically engaged.26 However, though EFL teachers should shoulder the responsibilities as equity agents,10,27,28 inequities are still evident in EFL teachers’ classroom teaching,29 which mainly reflect in teachers’ dominance in the discourse power over the classroom30,31 and their weak awareness to cater to students’ learning needs.32,33

So, why EFL teachers’ practices are not equitable and inclusive? As Borg’s34 teacher cognition framework illustrates, teachers’ practices are influenced by their cognitions and a series of experiential and contextual factors existing in and outside of the classroom. Specifically, teacher cognition refers to mental constructs, such as thoughts, knowledge, and beliefs, which are pertinent to teachers’ pedagogical practices. Experiential factors relate to the previous personal experiences of teachers, both as learners and educators while contextual factors include social, psychological, and environmental elements that are beyond teachers’ control, such as curricula, materials, colleagues and class size. Conceivably, there is an interrelationship between teachers’ cognition and practices regarding equity. However, it has been conclusively assumed that though teachers in this transformative age generally hold a strong belief that they should act as equity agents10,28,35 and have enhanced their equity consciousness and equity literacy,36 EFL teachers still fail to practice equity well in their actual teaching.37,38 Empirical findings from studies conducted by Chen,39 Erling et al,40 and Sulistyowardani et al41 have indicated that, even though EFL teachers claim to be devoted to equity in their teaching, their actions are not always consistent owing to the interplay of various factors such as insufficient training programs on equity and justice,42,43 lack of support from school authority27,44 and exam-oriented doctrines.30,45 In a word, though EFL teachers attempt to fulfill their obligation as equity agents, they are inevitably restricted by a series of influential factors within their teaching context.

Since equity is a “moral obligation” in a society founded on democratic morality,2 the intricate relationship between EFL teachers’ cognition and practices of equity deserves more scholarly attention. However, though there is a mounting number of studies focused on exploring EFL teachers’ equitable teaching in an ever-changing world within educational scope, little academic attention has been paid to illuminating the complexity of teacher cognition and practices from an equity lens5,46 and there is still little agreement on what factors contribute to the cognition-practice inconsistency in the EFL teaching context. Therefore, in this study, an equity perspective is adopted as a response to the increasing attention on identifying the factors that constrain teachers’ equitable teaching in the EFL teaching context, calling for collective efforts to address these factors so that a more “democratic, participatory, equitable, professional, and egalitarian future” for all learners can be built.47 This study has the potential to contribute to existing theories by providing empirical support that EFL teachers’ practices of equity are significantly influenced by their cognition and a variety of experiential and contextual factors. Additionally, this study proposes an effective framework for equity-focused EFL instruction that explicitly outlines the four key elements: experiential and contextual factors, teacher beliefs, and teaching practices.

Literature Review

The Definition of Educational Equity

The definition of educational equity has been much discussed over the decades. According to OECD,3 educational equity is broadly defined in two dimensions-fairness for “achieving the educational potential” and inclusion for “ensuring a basic minimum standard of education for all”. Similarly, in the definition given by Blankstein et al,48 equity is viewed as a commitment to guarantee all learners obtain what they need for achieving academic success. Though with a close relation to the three concepts - equality, justice and fairness in its nature,49,50 equity does not mean everyone should receive equal treatment or obtain the same academic results, instead, with richer connotation than equality,51,52 it outlines a scenario in which all the learners, even from marginalized groups, can have access to equal educational opportunities to learn and flourish, despite their race, gender, socioeconomic status or any other individual differences.53

In the EFL teaching context, the attainment of educational equity requires instructors to establish a fair and inclusive learning environment that addresses the diverse needs of every student. This involves adhering to the principle of fairness, which seeks to guarantee that every student has an equitable opportunity of realizing their educational potential, as well as promoting inclusion, which ensures that no student is excluded from accessing education on account of their background or circumstances. Accordingly, teachers should implement strategies across three levels: instructional, cognitive, and affective. Instructional strategies, including diverse learning materials14,15 and collaborative activities,16,17 can help ensure equity. Cognitive strategies such as eliciting diverse perspectives from students through open-ended questions18,19 and enhancing students’ critical thinking20 are also effective. Additionally, being culturally sensitive and responsive21 as well as showing care and love for students22,23 are crucial at the affective level.

Theoretical Background-Language Teacher Cognition Framework

The research on language teacher cognition today has grown into a sprawling field of inquiries,54 attracting greater attention to examining the intricacies of teachers’ cognitive worlds rather than solely concentrating on their pedagogical instruction.55 In the language teacher cognition framework developed by Borg,34 cognition is an immense concept that encompasses many constructs such as knowledge, belief and thoughts. Being tacit, systematic, and dynamic, cognition is initially shaped by teachers’ respective educational and professional experiences34,56 and its relationship with teachers’ practices is inevitably mediated by a series of contextual factors within the teaching context.57–59

Numerous empirical studies57,60,61 have examined the complex interplay between teachers’ implicit cognition and explicit practices, suggesting the significant role cognition plays in shaping their instructional practices. However, more studies62,63 have reported a distinctive discordance between teachers’ cognition and practices and identified a series of influential factors that mediate the cognition-practice relationship.

EFL Teachers’ Cognition of Equity

Given the significant role teachers’ cognition play in directing their practices of equity, a few studies have been done to illuminate the nature of equity-oriented cognition.64–67 Teachers with equity consciousness in mind hold the belief that students with diverse identity markers should be provided with equal access to academic success.66 Adopting a similar position, Ramaley67 emphasized that an equity mindset requires teachers to consistently think about what is truly needed to benefit their students’ academic progress, which is similar to the statement that teachers with equity in mind should “empower each student to transform themselves”.64

By surveying 452 American teachers with qualitative and quantitative approaches, Nadelson et al65 have further identified six attributes of teachers’ equity mindset, they are success for all, student-centered learning, understanding of student needs, responsibility for promoting equity and informal leadership. The findings not only clarify what constitutes teachers’ equity mindset but also suggest that teachers may hold completed or fragmented perspectives towards equity. Though a continued exploration of constructing an effective model of teachers’ equity mindset should be warranted,65 a consensus has been reached on the significance to urge teachers to develop a deeper understanding of issues and practices in terms of equity.68

When defining teachers’ equity-oriented cognition based on Borg’s cognition framework, the three main constructs, namely, knowledge, belief and pedagogical thinking34,56 were taken into account in this study. Accordingly, a teacher with equity cognition should have sufficient knowledge of equity, hold a strong belief in enhancing equity and form proper pedagogical thinking in implementing equity.

Without enough equity consciousness, equity may only become an empty buzzword.69 Thus, in response to the urgent need of addressing the educational concerns of equity, many EFL teachers have realized the significance of equity and have developed the correct cognition of equity. In a study conducted in Chile context, the findings revealed that EFL teachers could discern the differences between equity and equality which indicates that they possess some knowledge of equity.29 In terms of teachers’ belief in improving equity, the qualitative data extracted from three Hong Kong primary EFL teachers showed that teachers’ belief in equity is to provide support and care, especially for those who are disadvantaged and marginalized in the EFL classroom.27 Compared with the findings from previous studies claiming that EFL teachers only know little about equity as they define it merely from the dimension of equality29 and show no willingness to integrate equity in their teaching,70 teachers now are more equipped with equity-oriented cognition.

Equity-Oriented Cognition-Practice Inconsistency

Previous studies37,38 have reported that though holding a belief in equity, EFL teachers’ teaching is far from fairness and inclusion. An early study conducted by Lucas and Schecter71 has already reported an inconsistency between teachers’ cognition and practices in terms of equity, claiming that though teachers self-reported to be well aware of equity, what they do in the classroom is a different story. The mismatch between teacher cognition and practices is further supported by more recent studies done by Erling et al,40 Irgin72 and Sulistyowardani et al.41

Having recognized the discord existing in EFL teachers’ cognition and practices of equity, the factors that result in teachers’ lack of equity consciousness are also examined. As Chan and Lo27 and Wang and Gao43 argue, the concept of equity is rarely integrated into teacher education preparation programs. In a qualitative study, Buechel73 found that pre-service teachers often received insufficient training on reflecting their practices in terms of equity, and equality, which made it hard for them to enact equitable teaching. By acknowledging the role professional training plays in teachers’ cognition, more should be done to uphold equity in teacher education programs.74 In addition to the experiential factors, researchers also identified several contextual factors such as insufficient support from the school authority27,44 and exam-oriented doctrines27,30,45 that may contribute to the discordance of their cognition and practices.

Despite holding equity-oriented cognition, teachers are still not capable of integrating fairness and inclusion into classroom practices.42 Therefore, it is imperative to examine the contributing factors that caused EFL teachers’ cognition-practice inconsistency regarding equity. The conceptual framework for this study posits that teachers’ equity-oriented cognition and practices are influenced by a range of factors, including both experiential and contextual elements. Specifically, experiential factors such as teachers’ previous and professional experiences related to educational equity shape their initial cognition of equity in the classroom. In addition, contextual factors involving social, psychological and environmental elements that are beyond teachers’ control may also have an impact on their equity-oriented cognition and practices. Thus, a thorough understanding of these factors is essential for advancing equitable practices in EFL teaching, as it can assist in identifying areas where interventions and support may be needed to address disparities and promote more equitable outcomes. Besides, the analytical framework involves identifying specific variables related to experiential and contextual factors and analyzing their relationship with teachers’ equity-oriented cognition and practices, ultimately shedding light on the factors that impact equitable practices in EFL teaching.

Materials and Methods

Research Design

An interpretive qualitative research design75 was adopted to explore in depth the factors that contribute to the mismatch between teachers’ equity-oriented cognition and practices. According to interpretivism, knowledge is constructed when interpreting new experiences or concepts in the social context.76 As one common type of qualitative study, this research design is suitable for investigating how individuals experience and interact with the social context they are surrounded in. Therefore, it can allow the researchers to illuminate the factors that contribute to the inconsistency between teachers’ cognition and practices of equity in a systematic and profound manner.

Besides, in a qualitative study, the researcher acts as the main research instrument in the whole process,77 which means the researchers can immerse themselves into the particular natural setting and interpret what they observe through unique personal emic perspectives. In this study, the researcher chose to be an on-site nonparticipant, staying open-minded and objective to the emerging themes.

Research Context and Respondents

Since context is critical in studies involving teachers’ mental world, describing the context clearly can make the research process, methodological approaches and findings understandable and trustworthy. This study was conducted at MT University (a pseudonym) in the eastern part of China. MT University is widely recognized for its excellence in teaching the English language, as well as its unique local characteristics and global perspective. The university has solidified its reputation by offering a range of majors and disciplines that integrate English language instruction with specialized subjects. Notably, MT University was chosen for its emphasis on transforming conventional teaching approaches and cultivating teachers’ sense of equitable and quality teaching. Since 2016, MT University has implemented various educational reforms in response to the equity initiatives advocated by the Chinese government and the Ministry of Education (MOE). These reforms have been centered on promoting a student-centered educational philosophy, such as outcome-based education (OBE), and implementing student-oriented instructional approaches, including blended teaching and graded teaching. In addition, the university has encouraged teachers to attend equity-related seminars and training programs to enhance their cognition and instructional abilities. These efforts have inspired EFL teachers to pursue equity and excellence. However, despite the strong advocacy for equity in EFL teaching, teachers still encounter numerous challenges when attempting to integrate equity-oriented cognition into their instructional practices.

As for recruiting the respondents, criterion sampling, the common type of purposive sampling that select the samples according to the pre-set criteria,78 was adopted. To keep in line with the research aim, the inclusion criteria are set as follows:

- Engaging in EFL teaching

- Holding equity-oriented cognition

- Claiming to face challenges in practicing equity

- Volunteering to participate in the whole research process

- Aged from 25 to 60 years old

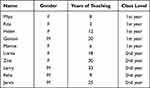

To recruit the respondents, a semi-structured interview was conducted to ask specific questions about what respondents know, believe and think about educational equity, whether they faced challenges in practicing equity in the classroom and whether they were willing to participate in the study. Eventually, we selected 10 EFL teachers with varying demographic profiles in terms of gender, years of teaching experience, and class level who demonstrated equity-oriented cognition as defined by OECD but also faced difficulties in integrating it within classrooms (see Table 1).

|

Table 1 Profiles of the Respondents |

Data Collection and Analysis

Grounded in Borg’s34 teacher cognition framework, the qualitative data about the contributing factors for teachers’ cognition-practice inconsistency were gathered from classroom observation and 60-minute stimulated recall interviews. In the first phase, the researchers observed the two sessions of the respondents’ class. As a crucial means of collecting firsthand data by investigating research subjects and sites,79 classroom observation is chosen for its efficacy in evaluating teaching practices and enhancing the instructional prowess of educators. During non-participant classroom observation, the researcher video-recorded the whole session for transcription. Besides, field notes were used to document instructional details and personal interpretations. The researcher focused on whether respondents had employed strategies at three levels. Indicators for instructional strategies included the utilization of varied learning materials14,15 and the integration of collaborative activities.16,17 Indicators of cognitive strategies were the use of open-ended questions18,19 and the emphasis on students’ critical thinking.20 Additionally, exhibiting cultural sensitivity and responsiveness21 and demonstrating care and love for students22,23 were deemed crucial at the affective level. To facilitate this process, the researcher employed a three-column format, with the left column recording the timing of events, the middle providing indicators of equity from the above-mentioned three dimensions (instructional, cognitive, and affective strategies) and descriptions of relevant classroom events, and the right reserved for reflective thoughts and comments. The researcher promptly wrote field notes during each observation, supplementing them with additional information from lesson recordings when necessary. Also, the classroom transcripts were prepared for analysis to triangulate the data.

Subsequently, based on the description of teaching episodes in the field notes, the researchers formulated the interview protocol (see Appendix 1) for the stimulated recall interviews, aiming to investigate the potential factors that shaped teachers’ actual practices. The stimulated recall interview was chosen because of its ability to extract real-time and interactive thoughts from teachers, as well as to obtain self-reflective insights into the intricate and unconscious nature of their pedagogical practices. Audétat et al80 argue that this methodology helps explore respondents’ cognitive processes by triggering their memories of concurrent thoughts. The protocol was originally written in Chinese and then back-translated into English, which was carefully examined by three experts in the English teaching area to ascertain its content and construct validity. After incorporating the experts’ suggestions, the protocol was refined into three phases. The first phase involved the replaying of selected episodes to stimulate respondents’ memory. This was followed by specific inquiries on the reasons behind the respondents’ practices. Finally, the protocol included some open-ended questions such as “What factors do you think may improve equity in classroom teaching?” and “What factors do you think may undermine equity in classroom teaching?” to elicit the respondents’ perceptions of the factors that influenced their pedagogical practices.

The interviews were performed in a quiet meeting room and a digital voice recorder was used to record the whole process. To obtain authentic and reliable data, the language used in the interview was their mother tongue - Chinese, then the researcher translated verbatim to ensure equivalency. During the interview, the researcher stayed attentive to the responses from the respondents and raised a series of prompts to elicit information as much as possible. Data saturation was achieved in these 10 respondents. All the interview data were transcribed into English for further analysis.

The collected observation and interview data were meticulously analyzed through thematic analysis conceptualized by Braun and Clarke.81 Given that most thematic analyses require the integration of both inductive and deductive components,82 this investigation adopted a combination of these two coding approaches to analyze the qualitative data. Specifically, the deductive aspect drew on pre-existing themes of experiential and contextual factors from the teacher cognition framework, while the inductive component facilitated the identification of new sub-themes.

The researchers first got familiar with the classroom observation transcripts, field notes and interview transcripts, then formulated initial codes and classified them into broader categories. Through rounds of careful review and an iterative process of analyzing the transcripts, these terms were regrouped again into more comprehensive themes. Additionally, Nvivo 12 was used to manage and process extensive qualitative data to visualize the findings.

To confirm the reliability of the findings, three experts were invited for checking the inter-rater reliability of the coding work. 50 coded samples were randomly selected and reviewed by the experts for measuring the agreements. The total reliability value was 94% which was in the acceptable range according to Miles and Huberman.83

Ethical Considerations

We certify that the study was conducted by the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. The study was initiated after getting approval from the official Ethics Committee named Jawatankuasa Etika Penyelidikan Manusia (JEPeM) in the Universiti Sains Malaysia (Ethical code: USM/JEPeM/21120837). And MT University has approved the study by providing a statement of academic integrity. To ensure every respondent’s willingness to participate in this study, written informed consent was obtained before the study. Also, the written material publication consent was included to confirm that the respondents agree to publish the study findings without disclosure of their identities.

Results

The observation data revealed that respondents’ classroom practices were not equitable and there does exist a discord between their cognition and practices. Further analysis was made through both observation and interview data to determine the underlying factors contributing to this discordance. Altogether 7 sub-themes under two themes experiential factors and contextual factors were identified (see Table 2).

|

Table 2 Final Coding Systems of Contributing Factors for Respondents’ Cognition-Practice Inconsistency |

Experiential Factors

The experiential factors that contribute to the cognition-practice inconsistencies were classified into two sub-themes, unpleasant schooling experiences and limited effective training.

Unpleasant Schooling Experiences

When relating to their former schooling experiences, some respondents talked about their unpleasant experiences of being treated unfairly by their teachers when learning English, wherein most of them were attributed to teachers’ adoption of self-centered teaching approaches, the exhibition of authority within the classroom environment and display of bias towards students. Respondents admitted that though they disliked being treated that way, they were inevitably affected by these negative influences and followed what their teachers did subconsciously in their teaching, as some stated:

When I was a college student, my teacher always dominated the classroom, giving us little time to think, talk and communicate with each other. We seemed to be dumb machines without any feelings. Ironically, my teaching has become that way too! (Zoe)

From my overseas learning experiences, I learned that being a student of a dictator is horrible and unbearable. My teacher never cared about what we wanted to learn, she forced us to take her views. Her style of teaching is by no means equitable and inclusive. I have to admit that I’ve been deeply influenced by her way of teaching. (Marcie)

When I studied abroad, my English teacher gave more attention to those who were native and often neglected Chinese students like me. I could sense the difference. But now when I become a teacher, I also have preferences for students who share the same origin as me. (Jarvis)

Limited Effective Training

The other contributing factor identified in respondents’ former experiences was limited effective training. Respondents acknowledged the significance of attending professional training programs in enhancing teachers’ equity pedagogy. However, training programs at or above the university level were still in scarcity and the training outcome was not satisfying. As Gaston revealed when asked why he did not practice equity in the classroom:

A lot of publishers have hosted many types of training for teachers and educators during holidays. I have attended some of them, I have to say, most of the programs are not useful for enhancing equity-related teaching philosophy and skills. Equity is not the goal of these programs. I don’t think attending these boring programs can enhance my teaching for equity. (Gaston)

In Gaston’s mind, most of the training programs offered by publishers were like “a paid vocation” which mainly provided an opportunity for teachers to relax instead of assisting them in learning the updated teaching philosophy or skills. Though having attended training programs many times, Gaston perceived that his attendance was mandatory by the university rather than for his personal growth and development. And he found no point in attending these training programs as they could hardly enhance his teaching for equity.

Contextual Factors

As for the contextual factors that exist in and outside of the classroom, five sub-themes, namely, unfavorable student factors, inharmonious classroom climate, toxic school contexts, equity-deficient education system, and negative social cultures were identified.

Unfavorable Student Factors

During observation, the researcher noticed that some students displayed a limited level of engagement with classroom activities and exhibited low motivation to share their ideas, despite the teacher’s efforts to provide interesting activities and encourage equal participation amongst all students. Upon being prompted to give presentations, these students either remained silent or simply responded with “Sorry, I don’t know”, which made it difficult for teachers to ensure fairness and inclusion in their teaching. As identified in the interview data, respondents reported their equitable teaching was affected by several unfavorable student factors such as students’ poor English language proficiency, low motivation and a weak sense of equity to some degree. For a start, students’ poor English language proficiency was considered one of the leading factors that kept them from being equitable. Zoe’s narration exemplifies the difficulty she encountered in ensuring equity in her classroom due to the inadequate English language proficiency of some of her students. Despite her efforts to provide equal opportunities to everyone, those with weak English language skills were unable to avail themselves of these opportunities, which made her wonder how could she maintain equity if the disadvantaged students could not enjoy the opportunities, as she put it:

Students’ poor English skills may impact my equitable teaching. Sometimes when I try to give opportunities for them to talk, some of them with weak English skills can’t take it. It’s hard to maintain equity if they are not able to take chances. (Zoe)

Besides, some respondents admitted their passion for equitable teaching died out when noticing students’ low motivation and passive participation in the whole teaching process. As in Lorna’s statement, she felt dismayed when seeing her students showing low motivation in the English classroom and admitted the dilemma she had encountered in the course of implementing equity, as she mentioned:

Another factor is students’ low motivation. Some students are indifferent to any activities I arranged for them. How can I practice equity when nobody even cares? (Lorna)

Students’ weak sense of equity may also result in their inequitable practices. In Gaston’s classroom, he was observed to only interact with active students in his class. As he explained, in his class, students would act as tamed sheep, showing no interest in taking initiative in their roles. The lack of sense of equity in students’ mindsets failed him to implement equity pedagogy efficiently.

It is a pity that some of our students don’t care about being put in such a tense and unequal situation, they are just like tamed sheep, following the lead. They just have no sense of equity and there is no atmosphere of healthy competition. I don’t know how to respond to such a phenomenon. (Gaston)

Inharmonious Classroom Climate

According to the observation data, the classroom climate of some respondents was not harmonious, mainly reflected in weak teacher-student bonds and detached peer relationships. Some respondents were found to have a poor rapport with their students. For instance, when questioned about why she called her students by their numbers, Marcie stated that she did not wish to build connections with her students for the belief that “teachers will run into trouble if they get too close to their students” as in the following statements. Her weak connection to her students resulted in a classroom climate that was far from fairness and inclusion.

I don’t want to remember students’ names. I don’t need to be their friend. Teachers will run into trouble if they get too close to their students. (Marcie)

In addition to the weak teacher-student bonds, according to the respondents’ accounts, the detached peer relationships that shaped the inharmonious classroom climate would also influence teachers’ equitable teaching. A healthy and amiable peer relationship can facilitate the learning atmosphere in the class. However, it is observed that in many respondents’ classes, students were reluctant to collaborate with their peers which made it difficult to promote collaboration among them. As in Larry’s case, he felt at a loss when his students were detached from others in group discussions.

When I asked my students to do group discussions, there are always some students who just sit there and can not find partners to share. I know I need to engage everyone in it, but I don’t know what I can do when they were so detached from each other. This is not my mistake, right? (Larry)

Toxic School Contexts

Notably, respondents’ teaching was greatly impacted by toxic school contexts including a lack of support from leaders and unfair evaluation mechanisms on teachers. During the process of classroom observation, the researcher detected that the majority of the respondents dominated the classroom by focusing primarily on analyzing the grammatical structure and displayed minimal involvement in utilizing activities that could foster critical thinking skills in students. When answering why so much attention had been paid to teaching grammar and vocabulary, Lorna revealed that the school leaders emphasized more on improving students’ college English tests (CET) pass rates instead of ensuring their sustainable development. The University did not prioritize equitable teaching, therefore, even equity-minded teachers had to follow the traditional teaching pattern since that “won’t go wrong”, as Lorna put it:

In our university, our leaders care more about the CET pass rates instead of students’ overall development. Though we know we should maintain equity, fulfilling their requirement can ensure that we “won’t go wrong”. (Lorna)

Besides, many respondents mentioned the unfair evaluation mechanisms on teachers made them disheartened and passive to enhance their teaching philosophy and skills. As Miya complained, the unfair evaluation mechanisms of the university should be blamed for making teachers exhausted from fulfilling other tasks rather than enhancing the teaching quality.

I think I should blame the unfair evaluation mechanisms of the university. They don’t see the value of good teachers. We are so exhausted from fulfilling the requirements like publishing papers and applying for grants. I hope the university can provide an equitable environment for teachers so that teachers can implement it in their teaching. (Miya)

Equity-Deficient Education System

The cognition-practice inconsistency was also caused by the current equity-deficient education system reflected in the exam-oriented doctrine and improper talent-training objectives. As observed, some respondents frequently raised the subject of CET exams and devoted a substantial portion of time to teaching exam skills to the students. It was expressed by the respondents that the exam-oriented doctrines still prevailed in China’s education system, as Helen stated, both teachers and students in China were over-focused on the academic results. Even though she knew the doctrines might keep her away from equitable practices, she had no clue how to change what was already rooted deeply in her teaching.

Chinese teachers and students have been plagued a lot by exam-oriented doctrines. Students were over-focused on their scores for they need a good academic background to secure a good job. Teachers were also keen on improving students’ scores since they were trained to do so. Even though I know being exam-oriented is improper, I don’t know how to change the status quo. (Helen)

The improper talent-training objectives also contribute to the cognition-practice discordance. Respondents like Jarvis and Gaston thought that higher education should not train people to think identically but inspire them to think innovatively. However, though many Chinese educators and policy-makers have highlighted the concept of educational equity in actual teaching, the talent-training objectives were still unchanged, meaning that teachers were trained to cultivate students for what society needs, not for what students want to be. The fact that it is difficult to cultivate talents with individuality through a standardized training approach made the equity goal in teaching hard to achieve, as exposed in Gaston’s statement:

Sadly, teachers are not trained for cultivating a free person, but a uniformed one. We have to stress more on making students the needed talents for social and economic development, do we ever care about what kind of persons our students want to be? How can teachers promote equity when they are required to cultivate students uniformly? (Gaston)

Negative Social Cultures

The most macroscopic factor is the negative social cultures in the specific Chinese context such as teacher authority embedded in Confucianism, demotivational culture as well as cell phone culture. As is known, Confucianism, the philosophical foundation of Chinese culture, has had a profound impact on education. Though Confucianism advocates loving students and teaching according to their aptitudes, the teacher authority embedded in it has put a threat to equitable teaching. While observing the class, the researcher noted that the majority of the respondents assumed a position of authority, which consequently led to the students following their lead and hesitating to question their instructions or decisions. As Lorna pointed out, English classrooms were featured with teachers’ dominance and students’ obedience.

Chinese people are deeply influenced by traditional Confucian culture in which the teacher represents the authority. Teachers often dominate the class and even demonstrate hegemony during teaching while students dare not to question or challenge teachers with different voices. (Lorna)

Moreover, another unfavorable culture – the so-called demotivational culture which has become prevalent in China is also closely related to teachers’ inequitable teaching. It was noted that a considerable number of students demonstrated a lack of interest in participating in classroom activities. Worse still, some students were observed to sleep through the whole class. In the interview, Marcie and Helen both mentioned the term demotivational culture. Marcie explained that demotivational culture reflects the Chinese young generations’ frustration and hopelessness. They lost motivation and passion for everything, as she described:

Being situated in a society with so much pressure and so many competitors, a lot of young Chinese seem to hold a ‘Lie Down’ mentality, nothing interests them. Influenced by such a negative mindset, they show no motivation in the classroom. (Marcie)

Worse still, such negative culture also dampened teachers’ passion for being qualified teachers. As Helen pointed out, teachers were also the victim of it since being a teacher is quite stressful these years due to the sudden change in the world context. She noticed that some teachers had also been influenced by the “demotivational culture” and lost their passion for work.

Additionally, many respondents highlighted the negative impact of the overwhelming cell phone culture, which was consistent with the researcher’s observation of many students indulging in the use of their mobile phones. Being addicted to their phones, students seldom show interest in English class. Larry expressed concerns about cell phone addiction as he felt powerless to turn his class into an active one where all students could get engaged, as he put it:

Students are now being slaves to their phones. My students can’t live without their phones, they seldom read books anymore, instead, they read on micro-blog. I don’t know what else I can do to involve them in my class… (Larry)

Discussion

From the observation and interview data, two sub-themes under the theme of experiential factors (unpleasant schooling experiences and limited effective training) and five under the contextual factors (unfavorable student factors, inharmonious classroom climate, toxic school contexts, equity-deficient education system, negative social cultures) were identified as the contributing factors for causing the inconsistency between teachers’ equity-oriented cognition and practices. Discussions are presented in the following sections.

On Experiential Factors

The findings that experiential factors may mediate the relationship between teacher cognition and practices correspond to the results in recent studies.84–86 The conclusion that respondents’ learning experiences affect their teaching is consistent with Rahman et al’s qualitative study,86 which found that past learning experiences did have an impact on English teachers’ cognition and practices. In a similar vein, the results of a quantitative study by Wei and Cao63 investigating the self-reported strategies of 254 EFL lecturers from universities in Thailand, China, and Vietnam lend credence to the claim that teachers’ pedagogical practices are somehow connected to their prior professional training experiences. Similarly, the findings of this current study corroborate Golombek’s87 assertions on the crucial role teachers’ previous experiences play in forming their cognition and affecting their practices.

Specifically, the experiential factors identified that have impacted EFL teachers’ equity-oriented practices are also reported in the previous findings. For instance, the results of Sulistyowardani et al’s study41 on two Indonesian English teachers’ cognition in integrating equity and justice in the classroom validated that teachers’ schooling experience was one of the major factors influencing their cognition about justice. Similarly, Mo30 pointed out that the EFL teachers may prioritize teaching reading skills solely to help students achieve high scores on tests rather than promoting students’ holistic development due to their own learning experiences.

The findings offer more substantial empirical evidence to support Llovet Vilà’s88 claim that teachers’ prior learning and professional experiences have a significant impact on their cognition and practices. However, it is notable that professional training on educational equity is still insufficient which is corroborated by the statement that the lack of training on improving equity may account for teachers’ inequitable teaching.42,43

On Contextual Factors

Notably, while acknowledging the importance of experiential factors, the study confirms that teachers’ experiences were not the sole source of teachers’ cognition and practices, as Gordon85 posits, the factors influencing and shaping teachers’ practices are complex and intertwined. The findings mirror those of the previous studies34,58 which have examined the association between context and teachers’ practices. For a start, most respondents mentioned how student individuality such as students’ poor English language proficiency, low motivation and a weak sense of equity may impact their practices of equity. Previous research30,59,89 has revealed similar findings. For instance, in qualitative research on Malaysian English teachers’ cognition of reading instruction, Philip et al89 emphasized that students’ academic levels might alter teachers’ instructional practices.

Secondly, in accordance with the present results, previous studies have supported the conclusion that respondents’ cognition-practice inconsistency may be attributed to the classroom climate.90,91 Respondents believed that a positive and encouraging teacher-student bond and peer relationship might help build a democratic classroom environment for learning and teaching while unpleasant relationships can inhibit the growth of both parties. This finding is consistent with that of Salinas,90 who discovered that the teaching environment and the connection between teachers and students might influence teachers’ practices. Likely, the empirical data of Gabryś-Barker’s91 study also demonstrated that a supportive classroom environment might enhance the well-being of both teachers and students which in turn could alter teachers’ pedagogical practices.

Thirdly, the study demonstrated that teachers’ teaching was somehow related to the school contexts, which collaborates with the results of earlier studies conducted by scholars like Luo et al58 and Woulfin and Gabriel.92 According to Cho,44 a democratic school atmosphere is recommended for enhancing justice and equality in teaching. Yet, some respondents claimed that a lack of support from the school leaders prevented them from maintaining equitable teaching, just as Chan and Lo27 found in their study that school leaders who were influenced by an exam-focused curriculum did not support their teachers to teach toward equity and excellence. This is also consistent with the findings of an empirical study by Oranje and Smith93 who discovered that insufficient support for equity-based teaching might explain the mismatch between their cognition and practices.

Fourthly, the findings can broadly support the work of other studies associating the Chinese education system, especially the exam-oriented education doctrines with EFL teachers’ inequitable practices.27,30,92 The majority of respondents agreed they had been affected by exam-oriented philosophies and as a result, they focused more on teaching skills to help students get high scores in exams. According to Liu et al,45 Mo,30 and Zhu and Shu,94 EFL teachers in China continue to place a high priority on passing the CET exams as their main goal. Yet, such an exam-focused mentality is in opposition to the equity goal advocated in SDG 4.

Finally, the findings also showed that respondents had been significantly impacted by Chinese social-cultural aspects, such as Confucianism, cell phone culture, and demotivational culture. Regarded as the cornerstone of traditional Chinese culture, Confucianism exerts great influence on Chinese teachers’ practices of equity. Previous investigations95,96 have found a complicated impact Confucianism has on changing teachers’ practices in the EFL teaching context. Confucian values, such as “education for all” and “worrying about unequal distribution but not scarcity”, can inspire teachers to employ suitable teaching strategies that address the varying learning needs of students. However, the centrality of teachers’ power and authority in Confucianism may also result in a more authoritarian teaching style.97 Furthermore, the findings indicated that the current mobile phone culture in the EFL classroom influenced respondents’ equity-related practices. The use of mobile phones created a new culture or subculture for teenagers which revolutionized teenage life across diverse cultures.98 Although previous studies99,100 have indicated the prevalence of the cell phone culture among students, no empirical investigation has yet explored the potential correlation between students’ addiction to this culture and EFL teachers’ equitable teaching practices. Another factor that was shown to have a detrimental impact on respondents’ equity-based practices was the demotivating culture. The term ‘demotivational culture’ refers to the negative psychological effects experienced by young individuals due to the stress, injustice, and disappointment they face in their social lives. This phenomenon is quietly emerging in today’s EFL classrooms in China. Nevertheless, prior research has not covered whether such culture has threatened teachers’ practices of equity, which requires more empirical evidence.

Implications and Conclusion

By taking a close look at teachers’ cognition and practices about equity, this interpretative qualitative study identified some key factors that contribute to equity-oriented cognition-practice inconsistency. Situated in the Chinese EFL context, the study offers valuable insights into Borg’s framework of language teacher cognition by providing empirical evidence that a range of experiential and contextual factors play a significant mediating role in the relationship between EFL teachers’ equity-focused cognition and their instructional practices. Notably, holding correct cognition of equity alone cannot guarantee the realization of equitable teaching for teachers. As Ladson-Billings101 argues, equity will only be realized when teachers have a clear understanding of what equity entails and become determined to take action to eliminate the injustices that hinder students’ development.

Therefore, to help teachers in the transformative age who are confronted with unprecedented challenges and opportunities to eliminate the negative effect of these factors and successfully translate their equity-bound cognition into practices, an equity-oriented teaching framework was proposed (see Figure 1). As Figure 1 illustrates, the framework contains all the elements needed for ensuring equity-oriented teaching. First of all, to cultivate correct cognition of equity, teachers should examine their knowledge, beliefs, and pedagogical thinking related to educational equity. In the meantime, the experiential factors and contextual factors that may harm teachers’ cognition and practices of equity should be meticulously recognized and carefully addressed within their teaching context. When ensuring that teachers are equipped with equity-based cognition and can mitigate the negative effect of potential constraining factors, they also need to employ instructional, cognitive and affective equitable strategies for building a fair and inclusive learning environment for all to flourish in quality learning experiences.

|

Figure 1 Equity-oriented teaching framework. |

In addition to enriching the existent literature on teachers’ cognition and practices of equity, the research findings can also be thought-provoking for urging teachers to reflect on their own beliefs, values, bias and pedagogical practices from an equity lens and for educators, policy-makers and any stakeholders to highlight equity in the future teacher education programs. Ensuring equity among all learners is the guarantee for a sustainable education102 and an important vehicle for reducing poverty and socioeconomic inequality across the globe.3 To answer Gorski’s103 call for educators to be transformational and equity-focused agents, the necessity of enhancing teachers’ equity-oriented practices in a world that is becoming more diverse, unequal and globalized, cannot be overstated. Therefore, given the crucial role equity plays in upholding social justice and creating a more inclusive and democratic society, due attention should be devoted to further uncovering more effective approaches to addressing factors causing equity-related cognition-practice mismatch in diverse educational contexts from interdisciplinary perspectives.

Data Sharing Statement

Original data related to the current study can be obtained by making a reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincerest gratitude to all the respondents for their participation in the study.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Jacob WJ, Holsinger DB. Inequality in education: a critical analysis. In: Holsinger DB, Jacob WJ, editors. Inequality in Education. CERC Studies in Comparative Education. Dordrecht: Springer; 2008:1–33.

2. Martínez Alemán AM. Reclaiming the moral case for educational equity. Change. 2020;52(2):95–98. doi:10.1080/00091383.2020.1732797

3. OECD. Policy Brief: Ten Steps to Equity in Education. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2008.

4. Sinagatullin IM. Developing preservice elementary teachers’ global competence. Int J Educ Reform. 2019;28(1):48–62. doi:10.1177/1056787918824193

5. Chen F, Abdullah RB. Teacher cognition and practice of educational equity in English as a foreign language teaching. Front Psychol. 2022;13:1–7. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.820042

6. Erling EJ, Radinger S, Foltz A. Understanding low outcomes in English language education in Austrian middle schools: the role of teachers’ beliefs and practices. J Multiling Multicult Dev. 2020;1–17. doi:10.1080/01434632.2020.1829630

7. Abdelmoula EK, Samira R, Abdelmajid B. A case study of differentiated instruction in the EFL reading classroom in one high school in Morocco. Int J Eng Lit Soc Sci. 2019;4(6):1862–1868. doi:10.22161/ijels.46.38

8. Al-Seghayer K. The central characteristics of successful ESL/EFL teachers. J Lang Teach Res. 2017;8(5):881–890. doi:10.17507/jltr.0805.06

9. Peng JE. The roles of multimodal pedagogic effects and classroom environment in willingness to communicate in English. System. 2019;82:161–173. doi:10.1016/j.system.2019.04.006

10. Boyd AS. Social Justice Literacies in the English Classroom: Teaching Practice in Action.

11. Crawford-Garrett K. The problem is bigger than us”: grappling with educational inequity in Teach First New Zealand. Teach Teach Educ. 2017;68:91–98. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2017.08.010

12. Murray DE. The world of English language teaching: creating equity or inequity? Lang Teach Res. 2020;24(1):60–70. doi:10.1177/1362168818777529

13. Montgomery PS, Roberts M, Growe R. English Language Learners: An Issue of Educational Equity. Lafayette: University of Lafayette; 2004.

14. Matuk C, Hurwich T, Spiegel A, Diamond J. How do teachers use comics to promote engagement, equity, and diversity in science classrooms? Res Sci. 2021;51:685–732. doi:10.1007/s11165-018-9814-8

15. Zhang X. Understanding reading teachers’ self-directed use of drama-based pedagogy in an under-resourced educational setting: a case study in China. Lang Teach Res. 2021;1–22. doi:10.1177/13621688211012496

16. Alrabah S, Wu S, Alotaibi AM. The learning styles and multiple intelligences of EFL college students in Kuwait. Int Educ Stud. 2018;11(3):38–47. doi:10.5539/ies.v11n3p38

17. Thorius KAK, Santamaría GC. Extending peer-assisted learning strategies for racially, linguistically, and ability diverse learners. Interv Sch Clin. 2018;53(3):163–170. doi:10.1177/1053451217702113

18. Hakim LN, Rachmawati E, Purwaningsih S. Teachers’ strategies in developing students’ critical thinking and critical reading. Pedagogia. 2020;10(1):11–19. doi:10.21070/pedagogia.v10i1.1036

19. Tang L. Exploration on cultivation of critical thinking in college intensive reading course. Engl Lang Teach. 2016;9(3):18–23. doi:10.5539/elt.v9n3p18

20. Haberlin S. Problematizing notions of critical thinking with preservice teachers: a self-study imparting critical thinking strategies to preservice teachers: a self-study. Action Teach Educ. 2018;40(3):305–318. doi:10.1080/01626620.2018.1486751

21. Meihami H. Culturally responsive teaching in TEFL programs: exploring EFL teachers’ experiences. Eng Teach Learn. 2023;47:119–144. doi:10.1007/s42321-022-00108-7

22. Xie X, Jiang G. Chinese tertiary-level English as a foreign language teachers’ emotional experience and expression in relation to teacher-student interaction. Front Psychol. 2021;12:759243. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.759243

23. Wang YL, Derakhshan A, Zhang LJ. Researching and practicing positive psychology in second/foreign language learning and teaching: the past, current status and future directions. Front Psychol. 2021;12:731721. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.731721

24. Ehrhardt-Madapathi N, Pretsch J, Schmitt M. Effects of injustice in primary schools on students’ behavior and joy of learning. Soc Psychol Educ. 2018;21(2):337–369. doi:10.1007/s11218-017-9416-8

25. Sun RY. EFL learners’ perceptions of classroom justice: does teacher immediacy and credibility matter? Front Psychol. 2022;13:1–6. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.925441

26. Schreiner LA. Different pathways to thriving among students of color: an untapped opportunity for success. About Campus. 2014;19(5):10–19. doi:10.1002/abc.21169

27. Chan C, Lo M. Exploring inclusive pedagogical practices in Hong Kong primary EFL classrooms. Int J Incl Educ. 2017;21(7):714–729. doi:10.1080/13603116.2016.1252798

28. Ham M. Nepali primary school teachers’ response to national educational reform. Prospect. 2020;5:1–22. doi:10.1007/s11125-020-09463-4

29. Leiva LR, Miranda LP, Riquelme-Sanderson M. Social justice in the preparation of English language teachers. Mextesol J. 2021;45(2):1–14.

30. Mo X. Teaching Reading and Teacher Beliefs: A Sociocultural Perspective.

31. Wu H. Reticence in the EFL Classroom: voices from Students in a Chinese university. J Appl Linguistics English Lit. 2019;8(6):114–125. doi:10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.8n.6p.114

32. El Khdar A, Rguibi S, Bouziane A. The need for educational equity through multimethodology and differentiation in the Moroccan EFL classroom. Stud Angl Resoviensia. 2019;16:33–47. doi:10.15584/sar.2019.16.3

33. Qi D, Rajab A, Haladin NB. From intensive reading teaching to outcome-based teaching: an empirical study on English reading in China. Int J Electr Eng. 2021;1–10. doi:10.1177/0020720920983510

34. Borg S. Teacher Cognition and Language Education: Research and Practice.

35. Guo L, Huang J, Zhang Y. Education development in China: education return, quality, and equity. Sustainability. 2019;11(13):1–20. doi:10.3390/su11133750

36. Bukko D, Liu K. Developing preservice teachers’ equity consciousness and equity literacy. Front Educ. 2021;6(3):1–11. doi:10.3389/feduc.2021.586708

37. Chen X, Vibulphol J. An exploration of motivational strategies and factors that affect strategies: a case of Chinese EFL teachers. Int Educ Stud. 2019;12(11):47–58. doi:10.5539/ies.v12n11p47

38. Xiong T, Xiong X. The EFL teachers’ perceptions of teacher identity: a survey of Zhuangang and Non-zhuangang primary school teachers in China. English Lang Teach. 2017;10(4):100–110. doi:10.5539/elt.v10n4p100

39. Chen FF. An empirical study of teacher-student interaction in college English classroom from the perspective of educational equality. Rev de Cercet Si Interv Soc. 2020;71:41–58. doi:10.33788/rcis.71.3

40. Erling EJ, Foltz A, Wiener M. Differences in English teachers’ beliefs and practices and inequity in Austrian English language education: could plurilingual pedagogies help close the gap? Int Multiling Res J. 2021;18(4):1–16. doi:10.1080/14790718.2021.1913170

41. Sulistyowardani M, Mambu JE, Pattiwael AS. Indonesian EFL teachers’ cognitions and practices related to social justice. Indones J Appl Linguistics. 2020;10(2):420–433. doi:10.17509/ijal.v10i2.28614

42. Grudnoff L, Haigh M, Hill M, Cochran-Smith M, Ell F, Ludlow L. Teaching for equity: insights from international evidence with implications for a teacher education curriculum. Curric J. 2017;28(3):305–326. doi:10.1080/09585176.2017.1292934

43. Wang D, Gao M. Educational equality or social mobility: the value conflict between preservice teachers and the Free Teacher Education Program in China. Teach Teach Educ. 2013;32:66–74. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2013.01.008

44. Cho H. Navigating social justice literacies: the dynamics of teacher beliefs in teaching for social justice. Asia Pac Educ Rev. 2018;19(4):479–491. doi:10.1007/s12564-018-9551-8

45. Liu D, Xue S, Hu R. A preliminary study on challenges and solutions for college EFL education in ethnic minority regions of China. English Lang Teach. 2019;12(3):15–25. doi:10.5539/elt.v12n3p15

46. Van Vijfeijken M, Denessen E, Van Schilt-Mol T, Scholte RHJ. Equity, equality, and need: a qualitative study into teachers’ professional trade-offs in justifying their differentiation practice. Open J Soc Sci. 2021;9:236–257. doi:10.4236/jss.2021.98017

47. Hult FM, Hélot C, Lin A, Kong H, Pennycook A. Criticality, Teacher Identity, and (In) equity in English Language Teaching.

48. Blankstein AM, Noguera P, Kelly L. Excellence Through Equity: Five Principles of Courageous Leadership to Guide Achievement for Every Student.

49. Panthi RK, Luitel BC, Belbase S. Teachers’ perception of social justice in mathematics classrooms. Math Educ Res J. 2018;7(1):7–37. doi:10.17583/redimat.2018.2707

50. Shaeffer S. Inclusive education: a prerequisite for equity and social justice. Asia Pac Educ Rev. 2019;20(2):181–192. doi:10.1007/s12564-019-09598-w

51. Barrow M, Grant B. The uneasy place of equity in higher education: tracing its (in) significance in academic promotions. High Educ. 2019;78:133–147. doi:10.1007/s10734-018-0334-2

52. Papastavrou E, Igoumenidis M, Lemonidou C. Equality as an ethical concept within the context of nursing care rationing. Nurs Philos. 2020;21(1):1–7. doi:10.1111/nup.12284

53. Klenowski V. Australian indigenous students: addressing equity issues in assessment. Teach Educ. 2009;20(1):77–93. doi:10.1080/10476210802681741

54. Burns A, Freeman D, Edwards E. Theorizing and studying the language-teaching mind: mapping research on language teacher cognition. Mod Lang J. 2015;99(3):585–601. doi:10.1111/modl.12245

55. Kyriakides L. Promoting equity in education. In: Mcelvany N, Holtappels HG, Lauer F, editors. Against the Odds: (In) equity in Education and Educational Systems. Münster: Waxmann; 2020:13–54.

56. Borg S. Teacher Research in Language Teaching: A Critical Analysis.

57. Gao LX, Zhang LJ, Tesar M. Teacher cognition about sources of English as a foreign language (EFL) listening anxiety: a qualitative study. Linguist Philos. 2020;19:64–85. doi:10.22381/LPI192020

58. Luo M, Main S, Lock G, Joshi RM, Zhong C. Exploring Chinese EFL teachers’ knowledge and beliefs relating to the teaching of English reading in public primary schools in China. Dyslexia. 2019;26(3):266–285. doi:10.1002/dys.1630

59. Sa’adah N, Maylawati DS, Sumardi D, Syah M. Teachers’ cognition about teaching reading strategies and their classroom practices.

60. Alzaanin EI. An exploratory study of the interplay between EFL writing teacher cognition and pedagogical practices in the Palestinian university context. Arab World Engl J. 2019;10(3):113–132. doi:10.24093/awej/vol10no3.8

61. Clark T, Yu G. Test preparation pedagogy for international study: relating teacher cognition, instructional models and academic writing skills. Lang Teach Res. 2022;1–19. doi:10.1177/13621688211072381

62. Ahmad I. Teacher cognition and grammar teaching in the Saudi Arabian context. English Lang Teach. 2018;11(12):45–57. doi:10.5539/elt.v11n12p45

63. Wei W, Cao Y. Written corrective feedback strategies employed by university English lecturers: a teacher cognition perspective. SAGE Open. 2020;10(3):1–12. doi:10.1177/2158244020934886

64. Brinegar K, Harrison L, Hurd E. Becoming transformative, equity-based educators. Middle Sch J. 2018;49(5):2–3. doi:10.1080/00940771.2018.1524253

65. Nadelson LS, Miller RG, Hu H, Bang NM, Walthall B. Is equity on their mind? Documenting teachers’ education equity mindset. World J Educ. 2019;9(5):26–40. doi:10.5430/wje.v9n5p26

66. Skrla L, McKenzie KB, Scheurich JJ. Using Equity Audits to Create Equitable and Excellent Schools.

67. Ramaley J. Educating for a changing world: the importance of an equity mindset. Metrop Univ. 2014;25(3):5–15.

68. Dawson E. Social justice and out-of-school science learning: exploring equity in science television, science clubs and maker spaces. Sci Educ. 2017;101(4):539–547. doi:10.1002/sce.21288

69. Williams D, Brown K. Equity: buzzword or bold commitment to school transformation. Instruc Leader. 2019;32(1):1–3.

70. Barahona M, Ibaceta-Quijanes X. Chilean EFL student teachers and social justice: ambiguity and uncertainties in understanding their professional pedagogical responsibility. Teach Teach. 2022;1–15. doi:10.1080/13540602.2022.2062726

71. Lucas T, Schecter SR. Literacy education and diversity: toward equity in the teaching of reading and writing. Urban Rev. 1992;24(2):85–104. doi:10.1007/BF01239354

72. Irgin P. Exploring teachers’ beliefs about listening in a foreign language. In: Turel V, editor. Exploring Teachers’ Beliefs About Listening in a Foreign Language. Hershey: IGI Global; 2021:199–220.

73. Buechel LL. Teachers as agents of change: unpacking EFL lessons through an anti-bias lens. In: Crawford J, Filback R, editors. TESOL Guide for Critical Praxis in Teaching, Inquiry, and Advocacy. Hershey: IGI Global; 2022:85–107.

74. Hu A, Verdugo RR. An analysis of teacher education policies in China. Int J Educ Reform. 2015;24(1):37–54. doi:10.1177/105678791502400104

75. Merriam S. Qualitative Research in Practice: Examples for Discussion and Analysis.

76. Hay C. Interpreting interpretivism interpreting interpretations: the new hermeneutics of public administration. Public Admin. 2011;89(1):67–82. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9299.2011.01907.x

77. Yin RK. Qualitative Research from Start to Finish.

78. Patton MQ. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods.

79. Creswell JW. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research.

80. Audétat MC, Cairo Notari S, Sader J, et al. Understanding the clinical reasoning processes involved in the management of multimorbidity in an ambulatory setting: study protocol of a stimulated recall research. BMC Med. 2021;21(1):1–7. doi:10.1186/s12909-020-02459-w

81. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

82. Braun V, Clarke V, Weate P. Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research. In: Smith B, Sparkes AC, editors. Routledge Handbook of Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise. London: Routledge; 2016:191–205.

83. Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook.

84. Çimen ŞS, Daloğlu A. Dealing with in-class challenges: pre-service teacher cognitions and influences. J Lang Linguist Stud. 2019;15(3):754–772. doi:10.17263/jlls.631499

85. Gordon J. Implementing explicit pronunciation instruction: the case of a nonnative English-speaking teacher. Lang Teach Res. 2020;1–28. doi:10.1177/1362168820941991

86. Rahman MM, Singh MKM, Salman Fersi M. Multiple case studies on the impact of apprenticeship of observation on novice EFL teachers’ cognition and practices. Mextesol J. 2020;44(4):1–11.

87. Golombek PR. Redrawing the boundaries of language teacher cognition: language teacher educators’ emotion, cognition, and activity. Mod Lang J. 2015;99(3):470–484. doi:10.1111/modl.12236

88. Llovet Vilà X. Language teacher cognition and curriculum reform in Norway: oral skill development in the Spanish classroom. Acta didact Norg. 2018;12(1):1–25. doi:10.5617/adno.5443

89. Philip B, Hua TK, Jandar WA. Exploring teacher cognition in Malaysian ESL classrooms. 3L. 2019;25(4):156–178. doi:10.17576/3L-2019-2504-10

90. Salinas D. EFL teacher identity: impact of macro and micro contextual factors in education reform frame in Chile. World J Educ. 2017;7(6):1–11. doi:10.5430/wje.v7n6p1

91. Gabryś-Barker D. Caring and sharing in the foreign language class: on a positive classroom climate. In: Gabryś-Barker D, Gałajda D, editors. Positive Psychology Perspectives on Foreign Language Learning and Teaching. Second Language Learning and Teaching. Berlin: Springer; 2016:155–174.

92. Woulfin S, Gabriel RE. Interconnected infrastructure for improving reading instruction. Read Res Q. 2020;55(S1):S109–S117. doi:10.1002/rrq.339

93. Oranje J, Smith LF. Language teacher cognitions and intercultural language teaching: the New Zealand perspective. Lang Teach Res. 2018;22(3):310–329. doi:10.1177/1362168817691319

94. Zhu Y, Shu D. Implementing foreign language curriculum innovation in a Chinese secondary school: an ethnographic study on teacher cognition and classroom practices. System. 2017;66:100–112. doi:10.1016/j.system.2017.03.006

95. Ding XW. The effect of WeChat-assisted problem-based learning on the critical thinking disposition of EFL learners. Int J Emerg Technol. 2016;11(12):23–29. doi:10.3991/ijet.v11i12.5927

96. Kung FW. Teaching and learning English as a foreign language in Taiwan: a socio-cultural analysis. TESL-EJ. 2017;21(2):1–15.

97. Gao HB. Confucianism. In: Yaden D, Zhao Y, Peng K, Newberg A, editors. Rituals and Practices in World Religions. Berlin: Springer; 2020:88–98.

98. Nurullah AS. The cell phone as an agent of social change. Rocky Mt Com Rev. 2009;6(1):19–25.

99. Roberts JA, Yaya LHP, Manolis C. The invisible addiction: cell-phone activities and addiction among male and female college students. J Behav Addict. 2014;3(4):254–265. doi:10.1556/JBA.3.2014.015

100. Yang Z, Asbury K, Griffiths MD. Do Chinese and British university students use smartphones differently? A cross-cultural mixed methods study. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2019;17(3):644–657. doi:10.1007/s11469-018-0024-4

101. Ladson-Billings G. “Makes me wanna holler”: refuting the “culture of poverty” discourse in urban schooling. Annals Am Acad Pol & Soc Sci. 2017;673(1):80–90. doi:10.1177/0002716217718793

102. Muyor-Rodríguez J, Fuentes-Gutiérrez V, De la Fuente-Robles YM, Amezcua-Aguilar T. Inclusive university education in Bolivia: the actors and their discourses. Sustainability. 2021;13(19):1–20. doi:10.3390/su131910818

103. Gorski PC. Reaching and Teaching Students in Poverty: Strategies for Erasing the Opportunity Gap.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.