Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

The Nexus Between High-Involvement Work Practices and Employees’ Proactive Behavior in Public Service Organizations: A Time-Lagged Moderated-Mediation Model

Authors Mehmood K, Iftikhar Y, Khan AN, Kwan HK

Received 8 December 2022

Accepted for publication 28 March 2023

Published 1 May 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 1571—1586

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S399292

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Mei-Chun Cheung

Khalid Mehmood,1 Yaser Iftikhar,2 Ali Nawaz Khan,1 Ho Kwong Kwan3

1Research Center of Hubei Micro & Small Enterprises Development, School of Economics and Management, Hubei Engineering University, Xiaogan, 432100, People’s Republic of China; 2AFPGMI, National University of Medical Sciences, Rawalpindi, 46000, Pakistan; 3Organizational Behavior and Human Resource Management Department, China Europe International Business School (CEIBS), Shanghai, 201206, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Ho Kwong Kwan, Organizational Behavior and Human Resource Management Department, China Europe International Business School (CEIBS), Shanghai, 201206, People’s Republic of China, Tel +86-13482520465, Email [email protected] Ali Nawaz Khan, School of Economics and Management, Hubei Engineering University, Xiaogan, 432000, People’s Republic of China, Tel +86-15695656712, Email [email protected]

Purpose: Public service organizations may improve the quality of services they offer citizens by instilling proactive behavior in their employees. This study aimed to provide insights on how high-involvement work practices may indirectly facilitate proactive behavior in frontline government employees via employee commitment.

Methods: A time-lagged approach was used to collect data from 542 frontline employees in three waves at 3-week intervals. We tested the hypothesized moderated mediation model using a PROCESS macro bootstrap approach.

Results: A moderated-meditation model was applied in which public service motivation was theorized to increase the mediating effect of employee commitment on the relationship between high-involvement work practices and employee proactive behavior. As predicted, the findings show that supervisor’ deviant behavior attenuated the mediating effect of employee commitment on the relationship between high-involvement work practices and employee proactive behavior.

Conclusion: The findings of this research contribute to the emerging literature on public management and have implications for public sector organizations seeking to improve the quality of services they offer citizens.

Keywords: public service motivation, supervisors’ deviant behavior, employee commitment, high-involvement work practices, employee proactive behavior, public sector

Introduction

This study examined an important question in public management: do high-involvement work practices (HIWPs) instill proactive behavior in public services organizations’ frontline employees in a transitioning economy? The success of China’s transition from a command economy to a free market economy is not yet universally heralded within the country, and the ethos of the former economic regime is firmly rooted.1 To a significant degree, the success of this transition depends on the success of human resources (HR) practices at the organizational level. Simply demanding compliance with governmental rules and organizational statutes and regulations is not enough to keep pace with the changing needs of a transitioning society. Rather, public service organizations must find ways to bridge the gap between themselves and citizens by encouraging their employees to engage in proactive work behavior, ie, to challenge the status quo and be more responsive to the needs of the public.2–4 The aim of this study is to examine the role of HIWPs in instilling such behavior in public service employees.

It has been established that HR practices not only affect employee behavior in general but can also encourage proactive behavior in employees.5 While proactive work behavior can vary in response to different HR practices, the common thread in all such behaviors is social exchange as an embodiment of organizational investment in HR practices. In particular, HIWPs, which represent an investment in human capital,6,7 are characterized by the sharing of decision-making powers and information (eg, business processes, business results, ensuing rewards, and work-system knowledge). HIWPs can thus prompt social exchange between employers and employees in public service organizations8,9 and motivate employees to work proactively for the common good of the organization, its customers, and themselves, rather than merely perform the tasks assigned by their managers.

Social exchange theory (SET) holds that employees perceive HR practices as an investment in themselves and therefore exhibit positive attitudes and behaviors—ie, commitment and proactive work behavior—in response to such practices.10 Hence, it can be said that the proactive work behavior of public servants is a reflection of their commitment that stems from their involvement in HIWPs. Such employees are more committed to their organizations and more likely to proactively challenge the status quo to improve public services than employees not involved in HIWPs. Moreover, public service motivation (PSM), ie, the altruistic intention to serve the public interest,11,12 adds to the effect of employee commitment (EC). Thus, it is reasonable to expect that PSM and EC may both interact with HIWPs to instill proactive work behavior, ie, employee proactive behavior (EPB), in public servants.

In China, managers have adapted their work behaviors to a free market framework, but the ethos of a command economy remains entrenched in many employees.13 Supervisors’ deviant behavior (SDB) is characterized by hostile verbal and non-verbal communication,14,15 in the form of shouting and angry outbursts, negative comments, public degradation, coercion, and the humiliation and belittling of employees.16 SDB can also manifest through behaviors such as taking credit for others’ efforts, blaming others for personal failures, and working with intentional slowness.17 SDB has been observed in public service organizations,18 and undermines the social exchange between employees and supervisors/managers. As supervisors represent an organization in the eyes of its employees, SDB is likely to weaken the social exchange between employees and the organization, even in the presence of HIWPs. Employees may take supervisor behavior into account when evaluating HIWPs, and distance themselves from their organization and its goals if they observe SDB. The resulting weakened social exchange is likely to undermine employee commitment and lead to a low valence of proactivity in response to HIWPs.

Drawing upon SET,10 this study examined the relationships between HIWPs, EC, EPB, PSM, and SDB. The primary objective was to investigate how HIWPs in public sector organizations influence EPB via EC. While several studies have researched the link between HR practices and proactivity in private sector employees,19,20 how this link manifests in public sector employees is underexplored, especially in transitioning economies such as that of China. As such, this study helps to fill an important gap in the public management literature. Another unique contribution of the study is its examination of the mediation effect of employees’ commitment between the HIWPs and EPB. One unique aspect of this study is that it focused on HIWPs (instead of general HR practices, as in previous studies) and their role in fostering EC and EPB. Parallel to the primary objective, this study also aimed to explore the moderating role of PSM in intensifying the links between HIWPs, EC, and EPB. Moreover, this study used a moderated-mediation mechanism to determine how PSM moderated EC’s mediation of the relationship between HIWPs and EPB (see Figure 1). This aspect is unique to this study, and it is a key contribution of this study to public management literature. Finally, whereas most studies have focused on the positive effects of leadership and HR practices on employee outcomes,20–23 this study explored the moderating effect of SDB in attenuating the impact of HIWPs on EC and, in turn, on EPB. Thus, this study is unique in considering a negative variable (ie, SDB) as a moderator that may reduce the effect of HIWPs on employee outcomes.

|

Figure 1 Conceptual Framework. |

Literature Review and Development of Hypotheses

HIWPs and EC

HIWPs are a set of HR practices that foster trust, commitment, motivation, and performance.24 The combination of these practices results in synergistic effects that improve employees’ communication, empowerment, and participation, and thus build their investment (physical and emotional) in their employer.25 HIWPs strengthen connections between employers and employees by aligning their goals, leading to more positive attitudes and behaviors in employees.26 For instance, an organization that invests in worker training is not only cultivating employees as a resource but is also increasing their skills and productivity, thus enhancing their development and promotion opportunities. Such initiatives increase employees’ involvement in an organization without external stimuli.27 HIWPs therefore empower and encourage employees to contribute in a participatory way to their organization, including through incentives and compensation.24 Overall, HIWPs enhance workers’ skills, sense of empowerment and participation, and alignment with organizational goals.

EC reflects the emotional attachment workers feel toward their employer and the alignment of their personal goals with their organization’s goals and also entails learning, excitement, collaboration, optimism, and enthusiasm.28 The social exchange between employees and their organization may leverage EC. For instance, given that EC is characterized by affection for one’s organization and pride in being part of it,29 committed employees are likely to stay with their organization because they want to, not because they must or should. Furthermore, the social exchange perspective suggests that when employees perceive that their organization is investing in them through HIWPs, they will reciprocate by working to benefit the organization.30,31 Specifically, when an organization engages in HIWPs, employees are likely to perceive that the organization is investing in their skill development (through training), involving them in organizational decisions, and rewarding them for their contribution.32 Employees may reciprocate by working to support organizational goals and being more committed.33 In short, employees are likely to be more committed to their organization when the organization is more committed to them.34 Therefore, we formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: A perception of greater HIWPs is associated with greater EC in public service organizations.

EPB and EC

The concept of EPB encompasses inner drive and personal initiative in pursuit of futuristic personal goals aligned with organizational goals.35 Thus, challenging the status quo instead of submitting to the current circumstances is a characteristic of EPB; a proactive individual takes the initiative in anticipation of a change in circumstances or even in his own person.36 EPB can manifest as whistleblowing; voicing crucial issues;37 pursuing issues until they are taken up seriously; proactively indulging in problem-solving exercises;38 striving for continuous improvements in work structures, designs, processes, and routines;39 proactively communicating, such as through feedback;40 or giving a helping hand to others.41 EC is demonstrated by employees behaving in ways that reflect attachment, such as by engaging in activities that advance organizational goals and serve organizational interests. EC is also likely to be reflected in behaviors such as dedicating oneself to goals, missions, and activities that serve the organization and its stakeholders.42 Therefore, EC can also translate into EPB.43

As SET extends the concept of exchange, HIWPs that generate EC in employees are likely to be reflected in their behavior. Specifically, committed employees are likely to behave in ways that embody their affective bond with the organization, supporting the best interests of the organization and its stakeholders. With their improved work ethic and dedication to the greater good, they are likely to act in support of organizational goals, activities, and strategies.44 Their commitment may translate into voluntary and proactive behavior to serve the public interest,45,46 even in the absence of rewards.47,48 Following this logic, we can anticipate a link between EC and EPB in public service organizations. Thus, we make the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2: Greater EC is positively related to EPB in public service organizations.

Mediator and Moderators for HIWPs and EPB

HIWPs, EC, and EPB: A Social Exchange Perspective

From the above discussion, social exchange in an organization can instill commitment, which, in turn, may foster EPB.49 Hence, from an SET perspective, the link between HIWPs and EPB can be explained by the mediating role of EC. HIWPs are a type of organizational investment in employees,50 reflecting an organization’s long-term focus on its human capital. Employees may feel obliged to reciprocate by viewing their organization as being worthy of their commitment, such that they form an affective bond with it.51 They may even feel gratitude and work to benefit the organization in return for its investment in them. As SET explains, this dynamic reflects the formation of a relationship in which there is exchange and reciprocity.52 In response to the benefits they reaped from HIWPs, employees will feel obligated to perform well in their jobs.53 If they feel that the organization has added to their well-being, they will feel a need to adopt behavior more favorable to the organization as a form of repayment.10 The more they feel that their organization is expressing care for them through HIWPs, the more obligated they will feel to reciprocate by exhibiting such favorable behavior. Therefore, HIWPs can help shape employee behavior that is beneficial to an organization, such as by making employees desirous of their organization’s success and empathetic toward its goals.

From a social exchange perspective, employees that benefit from HIWPs are likely to work proactively to contribute to their organization’s success. HIWPs such as training can teach employees about new opportunities for growth and instill new values in them.54 The alignment of the goals and values of employees and their organization is likely to expedite the social-exchange process.55 When an organization places trust in employees’ decision making, it gives them the courage to contribute proactively to such common goals. Empowered employees may behave proactively by redesigning processes for better performance.56,57 To summarize, HIWPs are an investment in employees, empowering them to be proactive in contributing to their organizational and personal goals by improving their public service.

Drawing upon SET, the link between HIWPs and EPB can be better explained indirectly by involving EC as an explanatory mechanism. Examining the effect of HIWPs on EC allows us to better explain their effect on EPB. As EC means that employees maintain their behavioral direction even in the absence of rewards,58 committed employees are likely to meet organizational goals while going above and beyond their normal duties and responsibilities to serve the public interest. Such EPB is a way for committed employees to contribute voluntarily to their organization. We can therefore predict a link between EC and EPB, and that EC mediates the interaction between HIWPs and EPB. Thus, we hypothesize as follows.

Hypothesis 3: EC mediates the positive link between HIWPs and EPB in public service organizations.

PSM

PSM is a prosocial value that induces employee behavior that is beneficial for the community and is distinct from employee outcomes.59 It also affects the performance of public service organizations.60 Public servants with higher PSM serve people without prejudice or favor, practice self-sacrifice, and show compassion in serving civic interests.61 They are committed to public service, public values, and public interests.

We can anticipate from an SET perspective that employees whose organizations involve them in HIWPs feel obligated to reciprocate this investment by becoming committed to their organization’s goals and desirous for their organization’s success, and that PSM may moderate this relationship between HIWPs and EC. Public service is based on notions of love, care, and duty toward a higher calling, as manifests as commitment beyond the need of the hour.62 PSM can be viewed as a general selfless motivation to act for the sake of a community, state, or society, outside of personal or organizational goals.63 The higher the PSM, the higher the commitment.64 Therefore, when public servants who are high in PSM find an organization worthy of their commitment, due to its involving its employees in HIWPs, these public servants’ desire to serve the public means that they will commit to this organization more strongly than would public servants with a lower PSM. High-PSM employees display characteristics such as self-sacrifice,65 which is likely to result in their commitment being manifest as positive behavior that benefits their organization and community. Hence, EPB can also arise due to the influence of PSM: highly committed employees with PSM may take part in changing and challenging the status quo to improve public services.

Moreover, employees with PSM, ie, a predisposition to act out of selfless motives, may derive a greater emotional impact from HIWPs.66 A stronger sense of social exchange emerges in such instances, leading to a stronger response to HIWPs. As a result, such employees may exhibit higher EPB, as their greater sense of being cared for by their organization may increase their EC and thus also increase their EPB. On this basis, we formulate our next hypothesis, as follows.

Hypothesis 4a: PSM moderates the positive link between HIWPs and EC in public organizations, such that the link is stronger for employees with high PSM levels than for those with low PSM levels.

Thus far, we suggest a moderated mediation model in which EC mediates the link between HIWPs and EPB and PSM moderates the relationship between HIWPs and EC. Building on the logic of Edwards and Lambert,67 we assume that PSM also moderates the strength of the EC-mediated relationship between HIWPs and EPB. Thus, we make a further hypothesis, as below.

Hypothesis 4b: PSM moderates the indirect effect of EC on the link between HIWPs and EPB in public service organizations, such that the indirect effect is stronger for employees with high PSM levels than for those with low PSM levels.

SDB

Not all supervisors or managers engage in positive behavior toward employees at all times.68 At times, some may exhibit SDB, by damaging equipment, leaving early, taking kickbacks, or showing favoritism.69,70 SDB may also involve supervisors verbally abusing, ignoring, or scorning their subordinates, or taking credit for others’ ideas or job performances.71 SDB is therefore detrimental to an organization and its other employees. Employees react to SDB by becoming negatively disposed toward managers breaching social norms15 and the reaction is amplified when workers are treated unfairly or without dignity.

SDB such as abuse may reduce EC,72 as due to the psychological distress such behavior causes in employees, they may reduce their efforts related to achieving organizational goals.71,73 As supervisors or managers represent the organization in the eyes of employees,74 employees deem the organization to be responsible for SDB. Just as positive treatment from managers makes employees feel cared for by their organization, the converse is also likely to occur: employees may blame the organization for letting them be treated badly by a misbehaving manager.75 Such perceptions may lead employees to doubt their organization’s intentions and HR practices.76 Hence, SDB (or such behavior by managers) can be expected to negatively affect EC. Even if HIWPs are implemented, EC may be impaired in the presence of SDB, and employees’ motivation to work toward organizational goals may be weakened. SDB is contrary to the organizational values that HIWPs attempt to impart.71 Thus, it signifies a gap between what an organization is trying to practice (HIWPs) and what is actually being practiced (SDB). If SDB persists, employees may come to regard their organization as insincere and its values as hypocritical. Witnessing SDB or perceiving that one is being treated unfairly is enough to demotivate an employee77 and make them feel detached from their organization and its mission.

Deviant behavior also harms social exchange relationships15 between employees and their managers and those between employees and their organization.74 As supervisors or managers represent an organization in the eyes of its employees, supervisors’ or managers’ behavior is taken as a signal of how the organization views its employees, who then use this signal information to judge whether to invest in a social exchange relationship with their organization.78 Deviant behavior by supervisors or managers may therefore lead employees to reduce their efforts and not invest in a social exchange relationship with the organization. In addition, if other members of a group or organization observe supervisors or managers exhibiting deviant behaviour, these members may also take part in shaping employees’ negative perceptions of their employer.79 As such, although employees may appreciate being involved in HIWPs, if they observe [or hear from others who observe) such deviant behaviour by their supervisor or manager, they may be less inclined to reciprocate being involved in HIWPs by showing EC and EPB in their organization. Thus, we make the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 5a: SDB negatively moderates the positive relationship between HIWPs and EC in public organizations, such that higher the level of SDB the weaker the relationship.

Thus far, we suggest a first-stage negatively moderated mediation model in which EC mediates the relationship between HIWPs and EPB, and SDB moderates the relationship between HIWPs and EC. Building on the logic of Edwards and Lambert,67 we assume that SDB also negatively moderates the strength of the EC-mediated link between HIWPs and EPB. Thus, we make the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 5b: SDB negatively moderates the indirect effect of EC on the link between HIWPs and EPB in public service organizations, such that the indirect effect is weaker in organizations with high levels of SDB than in those with low levels of SDB.

Methodology

Sample and Procedures

For this study, data were collected from frontline employees working in public service organizations in major municipalities located in the Yangtze River Delta region of the People’s Republic of China. Frontline employees act as a bridge between a public service organization’s internal operations and external customers and thus serve a vital function.20 One of the authors visited the public service organizations and contacted frontline employees, who were then briefed on the purpose of the study and the data collection procedures. The time-lagged approach was used in this study to collect data at different time intervals. The time-lagged method is widely used in the latest studies since it allows researchers to conduct several surveys for specific research.80–82 Scholars may collect data from multiple sources in this manner, eliminating the likelihood of common source bias.83–85 Moreover, this approach allows for data gathering at multiple time intervals, thus reducing the possibility of common method bias.86,87 Furthermore, before recording their final response, participants can reflect and take action on their behavior using this method. A pilot test of 50 respondents was conducted to assess the reliability of the scales used in the questionnaire, and minor modifications were made based on the respondents’ feedback. The theoretical constructs and items were checked for content validity. The items were firstly purified using corrected item-total correlation, and secondly, the unidimensionality were assessed using exploratory factor analysis with varimax rotation and principal components extraction. Furthermore, the intraclass correlation was calculated, and all the values were above 0.5, indicating an acceptable inter-rater agreement. The Cronbach’s alpha of all scales was found to be more than 0.7, which is acceptable.88

To reduce social desirability and the likelihood of common method variance,84 we collected data in three waves at three-week intervals. We targeted 1250 frontline employees working in these organizations. 1250 frontline employees were surveyed in the first wave (T1) of the study. There was a total of 958 questionnaires that were completed and returned with response rate of 76.64%. The employees were requested to answer the questions about HIWPs, PSM, and SDB, and provide their demographic information. Three weeks later, the 958 employees who had completed the first-wave survey were given the second-wave survey (T2), which concerned their EC. The number of usable responses returned was 750 with response rate of 78.29%. In the third-wave survey (T3), the employees who had completed the second-wave survey were requested to answer questions about their EPB, and 542 valid responses were received with response rate of 72.27%. The study sample comprised 70.1% males and 29.9% females, with an average age range of 31 to 40 years and an average tenure range of 6–10 years. The majority of the respondents had earned a bachelor’s degree or higher. The sample was composed mainly of frontline employees with a university degree. Before data collection, we conducted a statistical power analysis to establish the minimal sample size necessary to estimate the proposed model. With an anticipated effect size of 0.150, a desired statistical power of 80%, four predictors, and a confidence level of 0.95, the minimum needed sample size to estimate the model was 103.89,90 Our sample size was 542, satisfying this condition. According to this analysis, our study had the sufficient statistical power to detect the effects of interests.

Measures

All of the materials were presented in Chinese. Using the back-translation procedure, a management professor translated the materials from English into Chinese, and then two independent bilingual doctoral students back-translated the materials into English. All of this study’s responses were scored on a five-point Likert-type scale from “1 representing strongly disagree” to “5 representing strongly agree”. All scale items can be found in Appendix A. HIWPs were measured using nine items adapted from Searle et al,24 and the alpha value was 0.92. PSM was assessed using five items adapted from Miao et al,61 and the alpha value was 0.91. SDB was assessed using a six-item measure from Harris Harvey, and Kacmar,91 and the alpha value was 0.94. EC was assessed using six items adapted from Allen and Meyer,92 and the alpha value was 0.92. EPB was measured using eight items adapted from Parker, Williams, and Turner,93 and the alpha value was 0.87.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations of Variables

Table 1 shows the internal reliabilities of the predictors, outcome variables including means and standard deviations. HIWPs (r = 0.33, p < 0.01) and EC (r = 0.50, p < 0.01) was positively correlated with EPB. PSM was positively correlated with EC (r = 0.36, p < 0.01). In addition, SDB was negatively correlated with EC (r = −0.13, p < 0.05). All of the values of the correlation coefficients between the variables were less than 0.70, indicating that multicollinearity was not a serious problem. Thus, as these correlations were supported, we can analyze our hypotheses further.

|

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Matrix |

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

To measure the dimensionality of the data, CFA were performed using AMOS 24.0 to investigate the distinctive features of our model. The findings of the CFA revealed that the proposed five-factor model offered an acceptable fit to the data (see Table 2): a chi-square divided by the degrees of freedom (χ2/df) = 1143/517=2.21; a comparative fit index = 0.945; a Tucker–Lewis index = 0.941, and a root-mean-square error of approximation = 0.048. To examine discriminant validity of the hypothesized five-factor model, we compared it with four alternative models. HIWPs and PSM were combined into one factor in model four [χ2diff (4) = 1028, p < 0.01]; HIWPs, SDB, and PSM were combined into one factor in model three [χ2diff (7) =3743, p < 0.01]; HIWPs, SDB, PSM, and EC were combined into one factor in model two [χ2diff (9) =5074, p < 0.01]; and HIWPs, SDB, PSM, EC and EPB were combined into one factor in model one [χ2diff (10) = 6082, p < 0.01]. These alternative models did not produce acceptable fits, indicating that the model we used had discriminant and convergent validity (see Table 2). Furthermore, as shown in Appendix A, the composite reliabilities and factor loadings for our model were well above the acceptable ranges (greater than 0.80 and 0.60, respectively), thereby meeting the criteria recommended by.94 Hence, our statistical model was suitable for hypothesis testing.

|

Table 2 Results of Confirmatory Factor Analyses |

Hypothesis Testing

As exhibited in Table 3, HIWPs were found to be positively associated with EC (M2: β = 0.49, p < 0.001), which confirms Hypothesis 1. As expected, EC was positively associated with EPB (Model 7: β = 0.43, p < 0.001), which confirms Hypothesis 2. Hypothesis 3 suggested that EC mediates the relationship among HIWPs and EPB. As displayed in Table 4, when the EC factor was entered as an exclusive mediator between HIWPs and EPB, the results showed that there was a significant indirect effect of HIWPs on EPB via EC (β = 0.24, standard error (SE) = 0.03, p < 0.05, 95% confidence interval (CI) (0.18, 0.30)], thus confirms Hypothesis 3.

|

Table 3 Results for Hypotheses Testing for Direct and Moderating Relationship |

|

Table 4 Moderated-Mediation Results for Conditional Indirect Effects at the Values of Moderators |

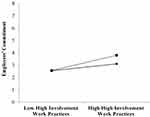

Hypothesis 4a posits that at higher levels of PSM, the positive link HIWPs and EC will be stronger. As displayed in Table 3, the interaction between HIWPs and PSM predicted EC significantly (M4: β = 0.17, p < 0.05). Furthermore, we plotted the interaction in accordance with at two PSM levels (± 1 standard deviation (SD)).95 Figure 2 reveals that the relationship between HIWPs and EC was stronger at higher levels of PSM, confirming Hypothesis 4a. Specifically, HIWPs were more positively related to EC when the level of PSM was high (β = 0.29, p < 0.05) rather than low [β = 0.15, p < 0.05). To examine Hypothesis 4b’s moderated mediation, we utilized Edwards and Lambert’s67 moderated path-analysis technique to estimate PSM (ie, the moderating variable]. Hypothesis 4b anticipated that PSM moderates the indirect effect of employee commitment on the link between HIWPs and EPB via EC. The results displayed in Table 4 indicate that the mediating effect HIWP on EPB via EC was significantly moderated by PSM (β = 0.17, p < 0.05). When the level of PSM was high, the mediating effect was 0.29 (p < 0.05), whereas when the level of PSM was low, the mediating effect was 0.15. Thus, Hypothesis 4b was supported. In addition, the index of moderated mediation did not include zero [index: 0.073; Boost SE = 0.029; 95% CI (0.017, 0.130)]; suggesting that the effect of PSM (ie, the moderator) on the indirect effect was significant.

Hypothesis 5a posited that SDB moderates the link between HIWPs and EC, with the association being weaker when the SDB level is high. The interaction between HIWPs and SDB was significantly and negatively related to EC (M6: β = −0.16, p < 0.05) (see Table 3). Furthermore, we plotted the interaction in accordance with Aiken and West’s (1991) at two SDB levels (± 1 standard deviation (SD)). The relationship between HIWPs and EC became weaker at higher levels of SDB, supporting Hypothesis 5a (see Figure 3). To examine Hypothesis 5b’s moderated mediation, we utilized Edwards and Lambert’s67 moderated path-analysis technique to estimate SDB (ie, the moderating variable). Hypothesis 5b anticipated that SDB moderates the link between HIWPs and EPB via EC. The results displayed that the mediating effect of HIWP on EPB via EC was significantly moderated by SDB (β = −0.16, p < 0.05) (see Table 3). When the level of SDB was high, the mediating effect was 0.15 (p < 0.05), whereas when the level of SDB was low, the mediating effect was 0.30. Thus, Hypothesis 5b was supported. In addition, the index of moderated mediation did not include zero [index: −0.07; Boost SE = 0.28, 95% CI (−.128, −0.019)]; suggesting that the effect of SDB on the indirect effect was significant.

Discussion

The findings of this study support the hypotheses regarding the associations between HIWPs, EC, PSM, SDB, and EPB. The results from the time-lagged study indicate that EC mediated the relationship between HIWPs and EPB. Moreover, SDB attenuated the relationship between HIWPs and EC, while PSM strengthened the relationship between HIWPs and EC. Furthermore, PSM moderated the mediating effect of EC on the link between HIWPs and EPB, such that the indirect effect was stronger when the level of PSM was high. In addition, SDB moderated the indirect effect of EC on the link between HIWPs and EPB, such that the indirect effect was weaker when the level of SDB was high. These findings have several theoretical and practical implications.

Theoretical Implications

The findings of this study contribute to the public management literature in several ways. First, they shed light on the link between HIWPs and EPB by exploring the mediating role of EC in the context of SET.10 SET is typically used to explain the mutual relationships between supportive top-down forces (transformational leadership or organizational support) and employees’ extra-role performance behaviors; however, less attention has been paid to the link between HR practices and EPB.96 As this study explored links between HIWPs and EPB through the mediating role of EC in public services organizations, the findings augment the power of SET to explain the link between HIWPs and EPB. Moreover, the finding that there was moderating role of PSM between HIWPs and EC in context of SET contributes to our understanding of the mechanism by which HIWPs affect EC. The social exchange between an organization and its employees involves a mutual exchange over and above personal interests and economic aspects.10 In addition, PSM refers to an altruistic intention to serve the public interest and embodies characteristics such as a commitment to public values, selflessness, and self-sacrifice.97 When extended toward a public service organization’s goals and mission, PSM generates the emotions and values necessary for employees to serve stakeholders over and above their personal interests.98 Hence, public servants with PSM respond positively to HIWPs and work proactively to serve stakeholders.

Our research also contributes to the literature on public value management. Recently, there has been an emphasis on empirical investigations into the effect of HR practices on employee outcomes in public service organizational settings.99 Therefore, our examination of PSM as a moderator of the commitment-mediated relationship between HIWPs and EPB via EC is timely. Previous studies have examined the moderating role of PSM in the relationship between leadership and job performance in public service organizations,100 but our work advances this stream of research by building on the idea that HIWPs also affect employee outcomes.101 Specifically, we posit that because HIWPs are a way for organizations to invest in their employees50 and align employee goals with organizational goals, such practices can strengthen public service values in employees, particularly those that already have PSM. In countries such as China, where a slow economic transformation process is underway,102 EPB can help overcome the slowness of change by improving public services and, in turn, public value management. Therefore, such countries should pay keen attention to EPB, which they have so far tended to neglect.103 In this work, we extended EPB research to the public sector, and introduced PSM to explain its mechanism.

Additionally, our research contributes to the HR management literature in the public service management context. Our results indicate that HIWPs can instilling EPB in public service employees by fostering EC. Our results also support previous findings; for example Gavino, Wayne, and Erdogan,50 showed that HR practices such as decision-making, performance management, and promotion opportunities have positive effects on employees outcomes. Their findings suggest that decision-making is more effective in inducing EPB than performance management, promotion opportunities, and training and development. Many public service organizations in China are continuing to use the traditional appraisal system, and thus employees in these organization have little decision-making power; moreover, this traditional system is not properly designed to reward EPB. Finally, our study included SDB in its analysis. Thus, this our findings expands the stream of literature on SDB research and extends it to the public sector. In the Chinese context, studying SDB in the public service management context is important due to the unfortunately frequent occurrence of SDB.104 This study was a pioneering foray into the study of SDB as a moderator between HIWPs and EC, which revealed that EC is a mediator between HIWPs and EPB.

Practical Implications

Our research also has important practical implications for management professionals in public service organizations. Supervisors or managers in such organizations can leverage EC and EPB by using HIWPs designed to stir such behavior in employees. First of all, training should be designed not merely to impart knowledge of organizational rules and regulations but also to instill public interest values, such as going above and beyond one’s statutory duties to provide better services to citizens, showing care for citizens, listening patiently, communicating with compassion, and patiently guiding citizens through complex procedures. At the same time, organizations should invest significantly in employees with respect to their performance improvement and career opportunities, so that employees will reciprocate by exhibiting higher EC and EPB. Second, Chinese organizations that still rely on traditional HR practices should complement them with suitable HIWPs to encourage employees to take a more active part in reaching organizational goals. For example, in China, the recruitment process relies heavily on guanxi, the system of social networks and relationships that can affect interactions and outcomes;105 public service organizations should complement this system with training and other HIWPs that can help align the goals and interests of organizations and their employees, thus facilitating higher EC. Third, public service organizations should develop strategies to increase their employees’ capabilities and motivation to serve the public, as higher PSM can lead to higher EC and EPB. For instance, inviting change agents from other successful organizations can help lift the level of EPB in an organization.106 Employees that exhibit high EPB may go beyond the call of duty to serve citizens, such as by going door-to-door to help the elderly, needy, and disabled. Fourth, offering appropriate training and opportunities for development and career growth can play an important role in an organization’s succession planning, whereby retiring employees are replaced by internally trained staff through promotion and succession. Organizations engaged in succession planning should work to cultivate public service values in employees, who can eventually become supervisors with a deep understanding of public policy and an ability to devise effective policies to contribute to China’s changing institutional framework. Fifth, in their performance appraisals, public service organizations should include measures to evaluate whether organizational investments in HIWPs have helped employees gain the desired knowledge, skills, and public service values. Whether they have become more proactive in response to HIWPs should also be measured. Moreover, performance systems should include measures to assess if HIWPs increase employees’ wish to strive toward their organization’s goals rather than their own goals, and compensation systems should be aligned with performance measurement such that they appropriately reward EPB through financial and non-financial means.

Through such well-designed HIWPs, supervisors or managers in public services organizations in China and other transitioning economies can leverage EC and EPB in their frontline employees. In addition, training and mentoring designed to overcome SDB can help to build a trained generation of supervisors who show genuine care for the public and their employees. As SDB can be an outcome of top-down appraisal systems, such systems should be amended to take feedback from diverse sources, including peers, colleagues, subordinates, and the public, and not just top management. This will inform those supervisors who exhibit SDB, thereby encouraging them to adjust their behavior to be more inclusive and caring toward subordinates.

Limitations

Our study has a few limitations. First, a study based on objective measures instead of perceptual measures may have resulted in better observability of variables such as SDB, HIWPs, and EPB. Hence, future research based on data from HR reports should be conducted. Similarly, EPB should be evaluated through organizations’ internal performance appraisal systems.107 However, future studies should further investigate PSM in different contexts, including various other public service organizations in China. Moreover, as the participants for this research were recruited from public service organizations in China, the findings cannot be generalized to other industries and cultural contexts.108 Therefore, further studies are necessary to broaden the scope and generalizability of the model to different geographical areas, cultures, and times.

Conclusion

With an aim to provide insights on how high-involvement work practices indirectly facilitate proactive behavior in frontline employees through their commitment, this study collected data from the frontline employees of public service organizations in China and empirically analyzed to test the proposed conceptual framework. The major insights from the study suggest that in the public service context, empowering employees to make decisions for the effective delivery of services to the public can increase EPB. In this regard, training and development can be useful in instilling skills relevant to public service and in fostering public service values that can strengthen employee commitment. Thus, compared to the traditional approach of merely imparting knowledge of public service policies, HIWPs can foster commitment through carefully designed training. Performance appraisal, a critical component of HIWPs, should also be amended to take feedback from multiple sources instead of merely relying on a supervisor’s evaluation. This study contributes to the existing body of knowledge and research on the public service management. We hope that our research may serve as a springboard for future research on the antecedents of EPB in public services organizations.

Data Sharing Statement

Data generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author by request.

Ethical Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and School of Economics and Management, Hubei Engineering University reviewed and approved the study protocol. All participants read and signed a consent form before they participated in the study. All participants read and signed a consent form before they participated in the study.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 71672108, 71672053) and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (grant number: 2020M671236).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Christodoulakis N. How Crises Shaped Economic Ideas and Policies: Wiser After the Events? In How Crises Shaped Economic Ideas and Policies: Wiser After the Events? Springer; 2015:155–170. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-16871-5

2. Fay D, Strauss K, Schwake C, Urbach T. Creating meaning by taking initiative: proactive work behavior fosters work meaningfulness. Appl Psychol. 2022;1–29. doi:10.1111/apps.12385

3. Hall EC, Cooper AA, Watter S, Humphreys KR. The role of differential diagnoses in self-triage decision-making. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2010;2(1):35–51. doi:10.1111/j.1758-0854.2009.01021.x

4. Sonnentag S. Recovery, work engagement, and proactive behavior: a new look at the interface between nonwork and work. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(3):518–528. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.3.518

5. Escrig-Tena AB, Segarra-Ciprés M, García-Juan B, Beltrán-Martín I. The impact of hard and soft quality management and proactive behaviour in determining innovation performance. Int J Production Economics. 2018;200:1–14. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2018.03.011

6. Thompson PS, Bergeron DM, Bolino MC. No obligation? How gender influences the relationship between perceived organizational support and organizational citizenship behavior. J Appl Psychol. 2020;105(11):1338–1350. doi:10.1037/apl0000481

7. Vranjes I, Notelaers G, Salin D. Putting workplace bullying in context: the role of high-involvement work practices in the relationship between job demands, job resources, and bullying exposure. J Occup Health Psychol. 2022;27(1):136–151. doi:10.1037/ocp0000315

8. Lavelle JJ, Rupp DE, Brockner J. Taking a Multifoci Approach to the Study of Justice, Social Exchange, and Citizenship Behavior: the Target Similarity Model. J Manage. 2007;33(6):841–866. doi:10.1177/0149206307307635

9. Mehmood K, Jabeen F, Iftikhar Y, et al. Elucidating the effects of organisational practices on innovative work behavior in UAE public sector organisations: the mediating role of employees’ wellbeing. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2022;1–19. doi:10.1111/aphw.12343

10. Blau PM. Exchange and Power in Social Life. New York: Wiley; 1964.

11. Kang YA, Baker MA. Which CSR message most appeals to you? The role of message framing, psychological ownership, perceived responsibility and customer altruistic values. Int J Hospitality Manage. 2022;106:103287. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2022.103287

12. Wright BE, Moynihan DP, Pandey SK. Pulling the Levers: transformational Leadership, Public Service Motivation, and Mission Valence. Public Adm Rev. 2012;72(2):206–215. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02496.x

13. Guiheux G. The ethos of Chinese capitalism: lessons from the career paths of Shanghai white-collar workers. Asian J German Eur Studies. 2018;3(1):1–18. doi:10.1186/s40856-018-0030-0

14. Ertz E, Becker L, Büttgen M, Izogo EE. An imitation game – supervisors’ influence on customer sweethearting. J Services Marketing. 2022;36(3):432–444. doi:10.1108/JSM-08-2020-0369

15. Zhang Y, Bednall TC. Antecedents of Abusive Supervision: a Meta-analytic Review. J Business Ethics. 2016;139(3):455–471. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2657-6

16. Dhanani LY, Beus JM, Joseph DL. Workplace discrimination: a meta-analytic extension, critique, and future research agenda. Pers Psychol. 2018;71(2):147–179. doi:10.1111/peps.12254

17. Stinglhamber F, Nguyen N, Ohana M, Lagios C, Demoulin S, Maurage P. For whom and why organizational dehumanization is linked to deviant behaviours. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2023;96(1):203–229. doi:10.1111/joop.12409

18. Rai A, Agarwal UA. A review of literature on mediators and moderators of workplace bullying. Manage Res Rev. 2018;41(7):822–859. doi:10.1108/MRR-05-2016-0111

19. Batistič S, Černe M, Kaše R, Zupic I. The role of organizational context in fostering employee proactive behavior: the interplay between HR system configurations and relational climates. Eur Manage J. 2016;34(5):579–588. doi:10.1016/j.emj.2016.01.008

20. Mehmood K, Jabeen F, Al Hammadi KIS, Al Hammadi A, Iftikhar Y, AlNahyan MT. Disentangling employees’ passion and work-related outcomes through the lens of cross-cultural examination: a two-wave empirical study. Int J Manpow. 2022;71672053. doi:10.1108/IJM-11-2020-0532

21. Bailey C, Madden A, Alfes K, Fletcher L. The Meaning, Antecedents and Outcomes of Employee Engagement: a Narrative Synthesis. Int J Manage Rev. 2017;19(1):31–53. doi:10.1111/ijmr.12077

22. Li W, Abdalla AA, Mohammad T, Khassawneh O, Parveen M. Towards Examining the Link Between Green HRM Practices and Employee Green in-Role Behavior: spiritual Leadership as a Moderator. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2023;16:383–396. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S396114

23. Lu Y, Zhang MM, Yang MM, Wang Y. Sustainable human resource management practices, employee resilience, and employee outcomes: toward common good values. Hum Resour Manage. 2022;1–23. doi:10.1002/hrm.22153

24. Searle R, Den Hartog DN, Weibel A, et al. Trust in the employer: the role of high-involvement work practices and procedural justice in European organizations. Int J Human Resource Manage. 2011;22(5):1069–1092. doi:10.1080/09585192.2011.556782

25. Boxall P, Macky K. Research and theory on high-performance work systems: progressing the high-involvement stream. Human Resource Manage J. 2009;19(1):3–23. doi:10.1111/j.1748-8583.2008.00082.x

26. Boon C, Den Hartog DN, Lepak DP. A Systematic Review of Human Resource Management Systems and Their Measurement. J Manage. 2019;45(6):2498–2537. doi:10.1177/0149206318818718

27. Brockner J, Flynn FJ, Dolan RJ, Ostfield A, Pace D, Ziskin IV. Commentary on “radical HRM innovation and competitive advantage: the Moneyball story”. Hum Resour Manage. 2006;45(1):127–145.

28. Hill NS, Seo M-G, Kang JH, Taylor MS. Building Employee Commitment to Change Across Organizational Levels: the Influence of Hierarchical Distance and Direct Managers’ Transformational Leadership. Org Sci. 2012;23(3):758–777. doi:10.1287/orsc.1110.0662

29. Meyer JP, Becker TE, Vandenberghe C. Employee Commitment and Motivation: a Conceptual Analysis and Integrative Model. J Appl Psychol. 2004;89(6):991–1007. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.89.6.991

30. Clausen T, Borg V. Psychosocial Work Characteristics as Predictors of Affective Organisational Commitment: a Longitudinal Multi-Level Analysis of Occupational Well-Being. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2010;2:182–203. doi:10.1111/j.1758-0854.2010.01031.x

31. Gould-Williams J, Davies F. Using social exchange theory to predict the effects of hrm practice on employee outcomes. Public Manage Rev. 2005;7(1):1–24. doi:10.1080/1471903042000339392

32. Zhong L, Wayne SJ, Liden RC. Job engagement, perceived organizational support, high-performance human resource practices, and cultural value orientations: a cross-level investigation. J Organ Behav. 2016;37(6):823–844. doi:10.1002/job.2076

33. Kehoe RR, Wright PM. The Impact of High-Performance Human Resource Practices on Employees’ Attitudes and Behaviors. J Manage. 2013;39(2):366–391. doi:10.1177/0149206310365901

34. Kuvaas B. An Exploration of How the Employee?Organization Relationship Affects the Linkage Between Perception of Developmental Human Resource Practices and Employee Outcomes. J Manage Studies. 2007;45(1):1–25. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.2007.00710.x

35. Anderson N, Potočnik K, Zhou J. Innovation and creativity in organizations: a state-of-the-science review, prospective commentary, and guiding framework. J Manage. 2014;40(5):1297–1333. doi:10.1177/0149206314527128

36. Grant AM, Ashford SJ. The dynamics of proactivity at work. Res Org Behav. 2008;28:3–34. doi:10.1016/j.riob.2008.04.002

37. Parker SK, Bindl UK, Strauss K. Making Things Happen: a Model of Proactive Motivation. J Manage. 2010;36(4):827–856. doi:10.1177/0149206310363732

38. Bakker AB, Tims M, Derks D. Proactive personality and job performance: the role of job crafting and work engagement. Human Relations. 2012;65(10):1359–1378. doi:10.1177/0018726712453471

39. Wrzesniewski A, Dutton JE. Crafting a Job: revisioning Employees as Active Crafters of Their Work. Acad Manage Rev. 2001;26(2):179–201. doi:10.5465/amr.2001.4378011

40. Zhang Z, Wang M, Shi J. Leader-Follower Congruence in Proactive Personality and Work Outcomes: the Mediating Role of Leader-Member Exchange. Acad Manage J. 2012;55(1):111–130. doi:10.5465/amj.2009.0865

41. Ilgen DR, Hollenbeck JR, Johnson M, Jundt D. Teams in Organizations: from Input-Process-Output Models to IMOI Models. Ann Rev Psychol. 2005;56(1):517–543. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070250

42. Mathieu JE, Zajac DM. A review and meta-analysis of the antecedents, correlates, and consequences of organizational commitment. Psychol Bull. 1990;108(2):171–194. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.108.2.171

43. Strauss K, Griffin MA, Parker SK. Future work selves: how salient hoped-for identities motivate proactive career behaviors. J Appl Psychol. 2012;97(3):580–598. doi:10.1037/a0026423

44. Steers RM, Mowday RT, Shapiro DL. The Future of Work Motivation Theory. Acad Manage Rev. 2004;29(3):379–387. doi:10.5465/amr.2004.13670978

45. Dai Q, Dai Y, Zhang C, Meng Z, Chen Z, Hu S. The Influence of Personal Motivation and Innovative Climate on Innovative Behavior: evidence from University Students in China. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2022;15:2343–2355. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S381494

46. Salmela-Aro K, Upadyaya K. Role of demands-resources in work engagement and burnout in different career stages. J Vocat Behav. 2018;108:190–200. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2018.08.002

47. Meyer JP, Allen NJ, Smith CA. Commitment to organizations and occupations: extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. J Appl Psychol. 1993;78(4):538–551. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.78.4.538

48. Wiedemann AU, Gardner B, Knoll N, Burkert S. Intrinsic Rewards, Fruit and Vegetable Consumption, and Habit Strength: a Three-Wave Study Testing the Associative-Cybernetic Model. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2014;6(1):119–134. doi:10.1111/aphw.12020

49. Wilmot MP, Wanberg CR, Kammeyer-Mueller JD, Ones DS. Extraversion advantages at work: a quantitative review and synthesis of the meta-analytic evidence. J Appl Psychol. 2019;104(12):1447–1470. doi:10.1037/apl0000415

50. Gavino MC, Wayne SJ, Erdogan B. Discretionary and transactional human resource practices and employee outcomes: the role of perceived organizational support. Hum Resour Manage. 2012;51(5):665–686. doi:10.1002/hrm.21493

51. Erdogan B, Bauer TN, Taylor S. Management commitment to the ecological environment and employees: implications for employee attitudes and citizenship behaviors. Human Relations. 2015;68(11):1669–1691. doi:10.1177/0018726714565723

52. Cropanzano R, Anthony EL, Daniels SR, Hall AV. Social Exchange Theory: a Critical Review with Theoretical Remedies. Acad Manage Ann. 2017;11(1):479–516. doi:10.5465/annals.2015.0099

53. Xu T, Lv Z. HPWS and unethical pro-organizational behavior: a moderated mediation model. J Managerial Psychol. 2018;33(3):265–278. doi:10.1108/JMP-12-2017-0457

54. Gavino MC, Lambert JR, Elgayeva E, Akinlade E. HR Practices, Customer-Focused Outcomes, and OCBO: the POS-Engagement Mediation Chain. Employee Responsibilities Rights J. 2021;33(2):77–97. doi:10.1007/s10672-020-09355-x

55. Backes-Gellner U, Veen S. Positive effects of ageing and age diversity in innovative companies - large-scale empirical evidence on company productivity. Human Resource Manage J. 2013;23(3):279–295. doi:10.1111/1748-8583.12011

56. Chang PC, Ma G, Lin YY. Inclusive Leadership and Employee Proactive Behavior: a Cross-Level Moderated Mediation Model. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2022;15:1797–1808. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S363434

57. Fernandez S, Resh WG, Moldogaziev T, Oberfield ZW. Assessing the Past and Promise of the Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey for Public Management Research: a Research Synthesis. Public Adm Rev. 2015;75(3):382–394. doi:10.1111/puar.12368

58. Marques JMR, La Falce JL, Marques FMFR, De Muylder CF, Silva JTM. The relationship between organizational commitment, knowledge transfer and knowledge management maturity. J Know Manage. 2019;23(3):489–507. doi:10.1108/JKM-03-2018-0199

59. Sun JY, Gu Q. For public causes or personal interests? Examining public service motives in the Chinese context. Asia Pacific J Human Resources. 2017;55(4):476–497. doi:10.1111/1744-7941.12119

60. Wright BE, Grant AM. Unanswered Questions about Public Service Motivation: designing Research to Address Key Issues of Emergence and Effects. Public Adm Rev. 2010;70(5):691–700. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2010.02197.x

61. Miao Q, Newman A, Schwarz G, Cooper B. How Leadership and Public Service Motivation Enhance Innovative Behavior. Public Adm Rev. 2018;78(1):71–81. doi:10.1111/puar.12839

62. Denhardt RB, Denhardt JV. The New Public Service: serving Rather than Steering. Public Adm Rev. 2000;60(6):549–559. doi:10.1111/0033-3352.00117

63. Wright BE. Public Service and Motivation: does Mission Matter? Public Adm Rev. 2007;67(1):54–64. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00696.x

64. Ritz A, Brewer GA, Neumann O. Public Service Motivation: a Systematic Literature Review and Outlook. Public Adm Rev. 2016;76(3):414–426. doi:10.1111/puar.12505

65. Moynihan DP, Pandey SK. The Role of Organizations in Fostering Public Service Motivation. Public Adm Rev. 2007;67(1):40–53. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00695.x

66. Bos-Nehles AC, Meijerink JG. HRM implementation by multiple HRM actors: a social exchange perspective. Int J Human Resource Manage. 2018;29(22):3068–3092. doi:10.1080/09585192.2018.1443958

67. Edwards JR, Lambert LS. Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: a general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychol Methods. 2007;12(1):1–22. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.1

68. Xu AJ, Loi R, Lam LW. The bad boss takes it all: how abusive supervision and leader–member exchange interact to influence employee silence. Leadersh Q. 2015;26(5):763–774. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2015.03.002

69. Liem A, Renzaho AMN, Hannam K, Lam AIF, Hall BJ. Acculturative stress and coping among migrant workers: a global mixed‐methods systematic review. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2021;13(3):491–517. doi:10.1111/aphw.12271

70. Wang W, Mao J, Wu W, Liu J. Abusive supervision and workplace deviance: the mediating role of interactional justice and the moderating role of power distance. Asia Pacific J Human Resources. 2012;50(1):43–60. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7941.2011.00004.x

71. Tepper BJ. Abusive Supervision in Work Organizations: review, Synthesis, and Research Agenda. J Manage. 2007;33(3):261–289. doi:10.1177/0149206307300812

72. Schyns B, Schilling J. How bad are the effects of bad leaders? A meta-analysis of destructive leadership and its outcomes. Leadership Quarterly. 2013;24(1):138–158. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2012.09.001

73. Li L, Huang G, Yan Y. Coaching Leadership and Employees’ Deviant Innovation Behavior: mediation and Chain Mediation of Interactional Justice and Organizational Identification. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2022;15:3861–3874. doi:10.2147/prbm.s381968

74. Biron M, Bamberger P. Aversive workplace conditions and absenteeism: taking referent group norms and supervisor support into account. J Appl Psychol. 2012;97(4):901–912. doi:10.1037/a0027437

75. Barnes CM, Lucianetti L, Bhave DP, Christian MS. “You Wouldn’t Like Me When I’m Sleepy”: leaders’ Sleep, Daily Abusive Supervision, and Work Unit Engagement. Acad Manage J. 2015;58(5):1419–1437. doi:10.5465/amj.2013.1063

76. Farh CIC, Chen Z. Beyond the individual victim: multilevel consequences of abusive supervision in teams. J Appl Psychol. 2014;99(6):1074–1095. doi:10.1037/a0037636

77. Hannah ST, Schaubroeck JM, Peng AC, et al. Joint influences of individual and work unit abusive supervision on ethical intentions and behaviors: a moderated mediation model. J Appl Psychol. 2013;98(4):579–592. doi:10.1037/a0032809

78. Martinko MJ, Harvey P, Brees JR, Mackey J. A review of abusive supervision research. J Organ Behav. 2013;34(S1):S120–S137. doi:10.1002/job.1888

79. Ostrom E. Collective Action and the Evolution of Social Norms. J Eco Perspectives. 2000;14(3):137–158. doi:10.1257/jep.14.3.137

80. Haider S, Heredero C, Ahmed M. A three-wave time-lagged study of mediation between positive feedback and organizational citizenship behavior: the role of organization-based self-esteem. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2019;12:241–253. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S192515

81. Mehmood K, Alkatheeri BH, Jabeen F, Iftikhar Y. The impact of IT capabilities on organizational performance: a Mediated Moderation Approach. Acad Manage Proce. 2021;2021(1):13737. doi:10.5465/ambpp.2021.13737abstract

82. Ullah F, Wu Y, Mehmood K, et al. Impact of Spectators’ Perceptions of Corporate Social Responsibility on Regional Attachment in Sports: three-Wave Indirect Effects of Spectators’ Pride and Team Identification. Sustainability. 2021;13(2):597. doi:10.3390/su13020597

83. Begum S, Xia E, Mehmood K, Iftikhar Y, Li Y. The Impact of CEOs’ Transformational Leadership on Sustainable Organizational Innovation in SMEs: a Three-Wave Mediating Role of Organizational Learning and Psychological Empowerment. Sustainability. 2020;12(20):8620. doi:10.3390/su12208620

84. Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

85. Yu X, Mehmood K, Paulsen N, Ma Z, Kwan HK. Why Safety Knowledge Cannot be Transferred Directly to Expected Safety Outcomes in Construction Workers: the Moderating Effect of Physiological Perceived Control and Mediating Effect of Safety Behavior. J Constr Eng Manag. 2021;147(1):04020152. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0001965

86. Alkatheeri HB, Jabeen F, Mehmood K, Santoro G. Elucidating the effect of information technology capabilities on organizational performance in UAE: a three-wave moderated-mediation model. Int J Em Markets. 2021. doi:10.1108/IJOEM-08-2021-1250

87. Mehmood K, Jabeen F, Iftikhar Y, Acevedo-Duque Á. How Employees’ Perceptions of CSR Attenuates Workplace Gossip: a Mediated- Moderation Approach. Acad Manage Proce. 2021;2021(1):13566. doi:10.5465/AMBPP.2021.13566abstract

88. Nunnally JC An overview of psychological measurement. In: Wolman BB, editor. Clinical Diagnosis of Mental Disorders. Boston, MA: Springer;1978:97–146.

89. Shang Y, Mehmood K, Iftikhar Y, Aziz A, Tao X, Shi L. Energizing Intention to Visit Rural Destinations: how Social Media Disposition and Social Media Use Boost Tourism Through Information Publicity. Front Psychol. 2021;12. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.782461

90. Shang Y, Rehman H, Mehmood K, et al. The nexuses between social media marketing activities and consumers’ engagement behaviour: a two-wave time-lagged study. Front Psychol. 2022. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.811282

91. Harris KJ, Harvey P, Kacmar KM. Abusive supervisory reactions to coworker relationship conflict. Leadership Quarterly. 2011;22(5):1010–1023. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.07.020

92. Allen NJ, Meyer JP. The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. J Occupational Psychol. 1990;63(1):1–18. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8325.1990.tb00506.x

93. Parker SK, Williams HM, Turner N. Modeling the antecedents of proactive behavior at work. J Appl Psychol. 2006;91(3):636–652. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.91.3.636

94. Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2010.

95. Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage;1991.

96. Tavares SM, van Knippenberg D, van Dick R. Organizational identification and “currencies of exchange”: integrating social identity and social exchange perspectives. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2016;46(1):34–45. doi:10.1111/jasp.12329

97. Bozeman B, Su X. Public Service Motivation Concepts and Theory: a Critique. Public Adm Rev. 2015;75(5):700–710. doi:10.1111/puar.12248

98. Vandenabeele W. Government calling: public service motivation as an element in selecting government as an employer of choice. Public Adm. 2008;86(4):1089–1105. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9299.2008.00728.x

99. Perry JL, Vandenabeele W. Public Service Motivation Research: achievements, Challenges, and Future Directions. Public Adm Rev. 2015;75(5):692–699. doi:10.1111/puar.12430

100. Miao Q, Eva N, Newman A, Schwarz G. Public service motivation and performance: the role of organizational identification. Public Money Manage. 2019;39(2):77–85. doi:10.1080/09540962.2018.1556004

101. Mumtaz S, Rowley C. The relationship between leader–member exchange and employee outcomes: review of past themes and future potential. Manage Rev Quarterly. 2020;70(1):165–189. doi:10.1007/s11301-019-00163-8

102. Chen S, Jefferson GH, Zhang J. Structural change, productivity growth and industrial transformation in China. China Economic Rev. 2011;22(1):133–150. doi:10.1016/j.chieco.2010.10.003

103. Kearney C, Hisrich RD, Roche F. Public and private sector entrepreneurship: similarities, differences or a combination? J Small Business Enterprise Dev. 2009;16(1):26–46. doi:10.1108/14626000910932863

104. Huang J, Shi L, Xie J, Wang L. Leader–Member Exchange Social Comparison and Employee Deviant Behavior: evidence from a Chinese Context. Soc Behav Personality. 2015;43(8):1273–1286. doi:10.2224/sbp.2015.43.8.1273

105. DiTomaso N, Bian Y. The Structure of Labor Markets in the US and China: social Capital and Guanxi. Manage Org Rev. 2018;14(1):5–36. doi:10.1017/mor.2017.63

106. Pascale RT, Sternin J. Your company’s secret change agents. Harv Bus Rev. 2005;83(5):72–81.

107. Guenther TW, Heinicke A. Relationships among types of use, levels of sophistication, and organizational outcomes of performance measurement systems: the crucial role of design choices. Manage Account Res. 2019;42:1–25. doi:10.1016/j.mar.2018.07.002

108. Mehmood K, Li Y, Jabeen F, Khan AN, Chen S, Khalid GK. Influence of female managers’ emotional display on frontline employees’ job satisfaction: a cross-level investigation in an emerging economy. Int J Bank Marketing. 2020;38(7):1491–1509. doi:10.1108/IJBM-03-2020-0152

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.