Back to Journals » Journal of Healthcare Leadership » Volume 15

Preventing and Mitigating Inter-Professional Conflict Among Healthcare Professionals in Nigeria

Authors Adigwe OP , Mohammed ENA, Onavbavba G

Received 19 October 2022

Accepted for publication 2 December 2022

Published 6 January 2023 Volume 2023:15 Pages 1—9

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JHL.S392882

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Pavani Rangachari

Obi Peter Adigwe,1 Elijah N A Mohammed,2 Godspower Onavbavba1

1Office of the Director General, National Institute for Pharmaceutical Research and Development, Abuja, Federal Capital Territory, Nigeria; 2Office of the Registrar, Pharmacists Council of Nigeria, Abuja, Federal Capital Territory, Nigeria

Correspondence: Obi Peter Adigwe, Office of the Director General, National Institute for Pharmaceutical Research and Development, Abuja, Federal Capital Territory, Nigeria, Email [email protected]

Introduction: The primary obligation of healthcare professionals is the well-being of patients. Inter-professional conflict can prevent the achievement of this goal, thereby potentially putting patients in peril. This study aimed at articulating contextual strategies to mitigate and prevent inter-professional conflict among healthcare workers in Nigeria.

Methods: A cross sectional study was undertaken in various health facilities in Nigeria. Questionnaires were administered to healthcare professionals. Completed questionnaires were analysed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences. Descriptive and inferential statistical analyses were undertaken.

Results: A total of 2207 valid responses were included for analysis. Findings revealed that almost all the respondents (92.9%) indicated that the Ministry of Health has a key role in resolving conflict in the healthcare sector. Close to three quarters (70.4%) of the study participants disagreed that leadership of hospitals and health agencies be limited to a particular profession. Almost all the participants (90.15%) indicated that cognate administrative expertise and experience are critical for leadership. A strong majority of the sample (93.5%) opined that reforms are required in the leadership selection process of hospital and other healthcare agencies.

Conclusion: Due to the criticality of this issue to patients’ access to healthcare, findings from this study can underpin a proactive evidence based strategy that can comprehensively address inter-professional conflict among healthcare workers in Nigeria.

Keywords: inter-professional, conflict, healthcare, professionals, Nigeria, leadership

Introduction

Conflict can be described as a social situation where two parties struggle with one another due to incompatibilities in perspectives, beliefs, goals, or values.1 This struggle can consequently impede the achievement of predetermined goals. Although knowledge and value based interdisciplinary conflict is evident in many sectors, it appears to be more common in the healthcare setting.2

The occurrence of inter-professional conflict among healthcare professionals in Nigeria seems to have increased in recent years. The phenomenon has been reported to be widespread and dysfunctional, occurring at all levels of the healthcare system.3 Violence between different professional groups has been reported in some cases,4 and disharmony in the health sector has adversely affected the system. The lack of team spirit and claims of superiority of a particular group of professionals over others has impacted negatively on team spirit as well as the deployment of optimal professional services.5 The implied consequence is a reduction of quality of healthcare services alongside poorer health outcomes for Nigerians.

Interdisciplinary collaboration leveraging on expertise and knowledge of different health professionals offers better value for patient care.6 However, contrary to best practices in developed countries,7 collaboration among healthcare professionals in Nigeria is less than optimal. Conflict and interdisciplinary rivalry within health institutions have been implicated in setbacks to delivery of optimal care,8 whilst severe disruptions to healthcare service delivery in Nigeria have been reported in the past as a result of inter-professional conflict.9 Available evidence suggests that rivalry is more apparent in countries where the management of healthcare services rely on healthcare professionals rather than hiring specialist managers.10 This practice effectively extends the scope of inter-professional rivalry from service delivery to the managerial domain. Therefore, avoiding the negative consequences to health systems governance may require a contextualised understanding of how inter-professional dynamics have evolved.

A review of the literature revealed that within the Nigerian context, there has been little focus on undertaking an empirical understanding of conflict management among Nigeria healthcare workers with a view to developing contextual prevention and mitigation mechanisms. A significant proportion of research in this area seemed to have focused on causes of inter-professional conflict in the health sector.3,11–13 Undertaking a critical assessment of healthcare workers’ perspective on conflict management in the healthcare system can provide a bottom-up strategy for policy reforms which will create a better working milieu in Nigerian healthcare sector. This will in turn improve service delivery to patients. This study, therefore, aimed at better understanding the phenomenon from practitioners’ perspectives, whilst developing evidence based robust and contextual strategies to prevent and mitigate conflict in the Nigerian healthcare industry.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was developed to assess views of Nigerian healthcare professionals on strategies to mitigate and prevent inter-professional conflict and rivalry in the healthcare sector. A questionnaire (see Supplementary Material) was designed for the study following an extensive literature review.14–18 An iterative process involving a panel of researchers with research activities in this area was used to develop the items on the data collection tool. A draft version of all the items on the instrument was reviewed by the panel; each person reviewed the items independently and suggested changes, additions, and deletions. The process continued until a consensus was achieved. The items on the questionnaire were structured to gain insights on measures that could help in preventing and mitigating inter-professional conflict among healthcare professionals.

Following the questionnaire design, the tool was exposed to face and content validation using an expert model. The questionnaire was assessed for appropriateness, complexity, attractiveness and relevance. Some of the statements were edited and reworded, whilst content validity was evaluated by quantitative method. Content validity ratio and content validity index were tested for each item, and only those that passed these tests were included in the final questionnaire. Pretesting of the questionnaire was undertaken by administration to an initial cohort of 30 participants comprising different healthcare professions that were randomly selected. The feedback received did not result in any major changes. These 30 questionnaires were therefore included in the final analysis.

Data were collected using online and physical methods, this was to ensure that a good number of healthcare professionals participated in the study. The participants were selected using a stratified sampling method. Two states were selected randomly from six geopolitical zones in Nigeria. Snowball sampling strategy was employed during the online data collection process,19,20 and this involved the use of WhatsApp. The link to the survey was sent to various groups made up of current practicing healthcare professionals, participants were asked to send the questionnaire to their colleagues practicing in the same state with them. Healthcare professionals who clicked on the link were directed to Google forms to complete the questionnaire. Paper-based questionnaires were administered physically to doctors, pharmacists, medical laboratory scientists, nurses, and other healthcare workers in several healthcare facilities that were randomly selected from each state using a convenience sampling method.21 The physical administration commenced after the link to online data collection was closed. Prior to the paper-based questionnaire administration, participants were requested to indicate if they had previously responded to the online version of the questionnaire, and only healthcare practitioners who did not participate during the online data collection process were given hard copies of the questionnaire to complete. The data collection was undertaken from April to June 2021.

Inclusion criteria were healthcare professionals who are currently practicing in Nigeria, and with current annual license to practice. And all participants who did not meet these criteria were excluded from the study.

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the National Health Research Ethics Committee of Nigeria prior to the commencement of data collection. Participation in this study was voluntary as informed consent was sent along with the online questionnaire, whilst for physical respondents, consent was obtained from them before administering the questionnaires. Confidentiality was maintained by not including the names of the study participants in the data collection tool.

Data retrieved from the survey were prepared in Microsoft Excel format and rechecked for accuracy. The data were then imported into Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 25, for analysis. Descriptive statistical analyses were undertaken, and chi square test was used to determine the association between responses and socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants. A p-value of 0.05 or less represented the threshold for statistical significance.

Results

Demography

A total of 2207 valid responses were received. Of the total number of respondents, two-thirds were males, a third of the participants (34.3%) were educated up to Master’s degree level. Professionally, a third of the sample (33.9%) were physicians, whilst a similar proportion were pharmacists (31.5%). A significant proportion of the sample were in the senior cadre (68.2%) whilst a strong majority of the study participants worked in the public sector (82.5%). Further details on socio-demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1.

|

Table 1 Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Respondents |

Role of Regulation and Legislation

Almost all the participants (92.9%) in this study indicated that the Ministry of Health had a key role in resolving inter-professional conflict, and a strong majority of the respondents (86.5%) were in consensus that professional registration boards and councils were critical in ending conflict in the healthcare sector, whilst a similar proportion (86.6%) agreed that legislation was required to end inter-professional conflict. It also emerged, that the management of agencies was implicated in inter-professional conflict. Figure 1 gives an overview of role of government ministries and agencies in preventing conflict among healthcare professionals.

|

Figure 1 Role of government in preventing conflict. |

Findings in this study suggest the need for an integrated multi-pronged strategy involving all critical stakeholders in the healthcare sector, as it is clear that leadership of the healthcare and other relevant actors have various roles to play in preventing conflict in the Nigerian healthcare system.

Leadership Requirements for Hospitals and Health Agencies

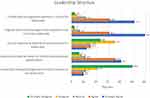

In this study, it emerged that more than two thirds of the study participants (70.4%) disagreed that leadership of hospitals and health agencies be limited to one profession. A slightly higher proportion (75.8%) of the sample indicated that leadership should be based on relevant post graduate qualifications. Regarding clinical expertise and leadership, more than a quarter of the participants (26.9%) indicated that experience in this area was necessary for leadership, whilst over half of the respondents (58.2%) disagreed with this phenomenon. Interestingly, almost all respondents (90.15%) indicated that cognate administrative expertise and experience were critical for leadership. Other relevant details pertaining to leadership requirements for hospitals and health agencies are presented in Figure 2.

|

Figure 2 Leadership requirements for hospitals and health agencies. |

Findings from this study have provided insights into key areas requiring reforms. Therefore, evidence from this study can underpin future policy and practice reforms in the Nigerian healthcare system and appropriately address conflict among healthcare workers.

Leadership Reforms

As indicated in Figure 3, a strong majority of the study participants (93.5%) supported the introduction of reforms into the leadership selection process of hospitals and health agencies. Similarly, almost all the participants (97.9%) were of the view that collaborative working was key to the prevention of rivalry and conflict. In continuation of the same sentiment, the majority of the respondents (92.8%) agreed that organisational diversity should be considered in leadership reforms. Further details on views of the participants about leadership reforms are presented in Figure 3.

|

Figure 3 Leadership reforms. |

From the findings presented in Figure 3, evidence from the professionals’ perspective indicates that the indicated critical leadership reforms can underpin policy and practice initiatives to improve health systems delivery.

Conflict Prevention Strategies During Undergraduate Training

The majority of the study sample (95.2%) indicated that a deliberate emphasis on collaboration at undergraduate level of professional study can facilitate harmony. A similar proportion (95.9%) supported the need to indoctrinate mutual respect in healthcare training so as to prevent conflict. Other relevant details are presented in Figure 4.

|

Figure 4 Training requirements for conflict prevention. |

The emergent findings from this study can underpin conflict prevention strategies during undergraduate training which will consequently enhance inter-professional collaboration among healthcare workers at various professional practice levels. This novel strategy can improve patient centred care alongside the achievement of overarching health sector objectives.

Cross Tabulations

More physicians (34.5%) were of the view that leadership of hospitals/agencies should be limited to one profession, compared to pharmacists (6.3%), medical laboratory scientists (6.8%), nurses (16%), and other healthcare workers (26%). This finding was statistically significant (p < 0.001; X2 = 619.67; df = 20).

Whilst only a few pharmacists (11.1%), medical laboratory scientists (13.6%), and nurses (8.1%) indicated that clinical expertise and experience were necessary for leadership, about half (48.5%) of the physicians indicated that clinical expertise and experience were important for leadership. This finding, too, was statistically significant (p < 0.001; X2 = 645.48; df = 20).

A strong majority of pharmacists (77%), medical laboratory scientists (82.4%), and nurses (78.5%) indicated “strongly agree” to the item “reforms are required in leadership selection of hospitals/agencies” as compared to only 41.5% of physicians that indicated “strongly agree” to the item (p < 0.001; X2 = 318.33; df = 20). This novel, statistically significant, finding provides fresh insights as to professional proclivities with respect to potential reforms to the leadership structure in the Nigerian healthcare industry.

Discussion

In this study, a strong majority of the participants indicated that the Ministry of Health had a key role to play in resolving inter-professional conflict in the Nigerian healthcare sector. This suggests that from the perspective of Nigerian healthcare professionals, the Ministry was saddled with the obligation for contextual reforms that can prevent interdisciplinary conflict in the sector. Similarly, the participants were of the view that professional registration boards and councils had a critical role in ending inter-professional conflict in Nigeria whilst a considerable proportion of the respondents perceived that the Ministry of Labour also had a role to play in resolving conflict among healthcare professionals. These findings suggest that the responsibility of reforming healthcare leadership lies with the government, as its role in repositioning the sector cannot be overemphasised. Conflict among healthcare professionals can be detrimental to patients and the healthcare system. Conversely, timely and effective resolution has been associated with performance enhancement, increased patient safety, and improved healthcare outcomes.22 The promotion of a healthcare system underpinned by collaboration and cooperation between healthcare personnel can be headlined by the actors identified by this study’s novel findings. This crises prevention strategy has been adopted in many developed country settings and has been associated with positive outcomes for the healthcare sector.23,24 Findings in this study imply that a multidisciplinary policy backed intervention is needed to address conflict in the healthcare sector.

A strong majority of the respondents indicated that legislation was required to end inter-professional conflict. What this means is that there is a desperate need for a robust collaboration between the executive and legislative arm of government to articulate contextual policies which promote harmony in the Nigerian health care space. In other settings, this strategy has been used to achieve collaboration among healthcare workers.25 Also, findings from this study suggest that the management of respective health agencies may be implicated in fostering inter-professional conflict. The reason behind this is, however, not clear and further research based on this study’s results can provide more insights into this critical area.

This study also revealed that the majority of participants disagreed with the notion that the leadership of hospitals and health agencies be limited to one profession. This finding is in line with international best practices which requires that such leadership should be on the basis of competence, rather than professional affiliation.26,27 In Nigeria, the healthcare leadership sphere is dominated by physicians.28 This current practice has contributed significantly to conflict and rivalry in the sector.16,29 A review of leadership selection processes that prioritises management skills underpinned by necessary expertise and experience, is therefore critical at this point. Interestingly, more physicians in the study cohort were of the view that leadership be limited to one profession. This however may be due to the fact that the current leadership structure favours the medical doctors over other health care professionals that practice in the sector.

In a similar vein, three quarters of the study sample indicated that leadership be based on relevant post-graduate qualifications. This finding suggests that reforms in the healthcare sector considers the prioritisation of individuals with higher requisite academic qualifications. Also, a strong majority of the participants agreed that cognate administrative expertise and experience were critical for leadership. This finding is particularly important for policy reforms, as a previous finding suggests most challenges in the Nigerian health industry revolve around poor management.30 This position was validated in a study by Oleribe,31 where it was reported that a considerable proportion of healthcare managers in Nigeria lack adequate administrative knowledge and skills. Whilst the majority of the participants indicated that clinical expertise and experience were not necessary for leadership, a quarter of the participants disagreed with this perspective. Further chi square analysis revealed that the majority of those that indicated the criticality of clinical expertise and experience for leadership were physicians. The reason behind this may be based on the status quo ante where medical doctors dominate the leadership of healthcare establishments.

Further findings from this study revealed the need for leadership selection reforms for hospitals and other health agencies. However, only a few medical doctors supported leadership reforms in the healthcare sector as compared to other healthcare workers. Almost all the participants supported the need for collaborative working to be reflected in policy reforms. The finding aligns with other international studies that linked collaborative working with higher quality care and improved clinical outcomes.32,33 Whilst this study has identified that organisation diversity should be considered for leadership selection, the participants also agreed that leadership training is critical for all healthcare workers. Organising seminars, courses, and workshops pertaining to healthcare administration can help enhance the leadership skills of healthcare professionals.34,35

Regarding the training of healthcare professionals, findings from this study indicate that emphasising collaboration at undergraduate level can facilitate harmony among healthcare personnel, and this is in line with previous international work on this topic.36 Also, indoctrinating mutual respect in healthcare training was identified as an important means of preventing conflict in the healthcare industry. Nigerian healthcare sector is already faced with various challenges including Medicines’ Security,37 failing to appropriately address inter-professional conflict has tendency to exacerbate the challenges in the healthcare sector.

Conclusion

This study has provided insights on strategies to mitigate and prevent inter-professional conflict among healthcare workers. Findings from this study can underpin comprehensive and contextual policy reforms that can address conflict and rivalry in the Nigerian setting and consequently contribute to the achievement of Universal Health Coverage. Empirical evidence from the study indicated that the Ministries of Health and Labour, as well as other government agencies can play critical roles in preventing and resolving inter-professional conflict in the healthcare sector. What this means is that urgent reforms led by these entities can go a long way in repositioning the entire system for effective service delivery.

For the headship of healthcare agencies, a majority of healthcare professionals exhorted that rather than limiting selection to particular professions, appointments should be based on merit underpinned by competence, skills and relevant expertise. Collaboration among all healthcare professionals should also be deliberately encouraged, even from undergraduate professional training. Due to the criticality of this important issue, necessary further research needs to be undertaken to deepen these emergent findings.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. African Factory OO. Management: a study of some factories in Southern Nigeria. Afr Soc Rev. 1999;3(1):94–110.

2. Kazimoto P. Analysis of Conflict Management and Leadership for Organizational Change. Int J Res Soc Sci. 2013;3(1):16–25.

3. Mayaki S, Stewart M. Teamwork, professional identities, conflict, and industrial action in Nigerian Healthcare. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2020;13:1223–1234. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S267116

4. News Agency of Nigeria. JOHESU strike: NMA decries attacks on doctors, patients in Enugu. The guardian; 2018. Available from https://guardian.ng/features/johesu-strike-nma-decries-attacks-on-doctors-patients-in-enugu/.

5. Osaro E, Charles AT. Harmony in health sector: a requirement for effective healthcare delivery in Nigeria. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2014;1(7):S1–S5. doi:10.1016/S1995-7645(14)60196-6

6. Miller R, Combes G, Brown H, Harwood A. Interprofessional workplace learning: a catalyst for strategic change? J Interprof Care. 2014;28(3):186–193. doi:10.3109/13561820.2013.877428

7. Davies C. Getting health professionals to work together. BMJ. 2000;320(7241):1021–1022. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7241.1021

8. Astbury J, Yu VYH. Determinants of stress for staff in a neonatal intensive care unit. Arch Dis Child. 1982;57(2):108–111. doi:10.1136/adc.57.2.108

9. Adeloye D, David RA, Olaogun AA, et al. Health workforce and governance: the crisis in Nigeria. Hum Resour Health. 2017;15(1):1–8. doi:10.1186/s12960-017-0205-4

10. Kirkpatrick I, Dent M, Jespersen PK. The contested terrain of hospital management: professional projects and healthcare reforms in Denmark. Current Soc. 2011;59(4):489–506. doi:10.1177/0011392111402718

11. Ogbonnaya LU, Ogbonnaya CE, Adeoye-Sunday IM. The perception of health professions on causes of interprofessional conflict in a tertiary health institution in Abakaliki, southeast Nigeria. Nig J Med. 2007;16(2):161–168. doi:10.4314/njm.v16i2.37300

12. Iyoke CA, Lawani LO, Ugwu GO, et al. Knowledge and attitude toward interdisciplinary team working among obstetricians and gynecologists in teaching hospitals in South East Nigeria. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2015;8:237–244. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S82969

13. Olajide AT, Asuzu MC, Obembe TA. Doctor-nurse conflicts in Nigerian hospitals: causes and modes of expression. Br J Med Med Res. 2015;9(10):1–12. doi:10.9734/BJMMR/2015/15839

14. Stecker M, Epstein N, Stecker MM. Analysis of inter-provider conflicts among healthcare providers. Surg Neurol Int. 2013;4(Suppl 5):S375. doi:10.4103/2152-7806.120781

15. Aberese-Ako M, Agyepong IA, Gerrits T, Van Dijk H, Dalal K. ‘I used to fight with them but now I have stopped!’: conflict and Doctor-Nurse-Anaesthetists’ motivation in maternal and neonatal care provision in a specialist referral hospital. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0135129. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0135129

16. Omisore AG, Adesoji RO, Abioye-Kuteyi EA. Interprofessional rivalry in Nigeria’s health sector: a comparison of doctors and other health workers’ views at a secondary care center. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2017;38(1):9–16. doi:10.1177/0272684X17748892

17. Archambault‐Grenier MA, Roy‐Gagnon MH, Gauvin F, et al. Survey highlights the need for specific interventions to reduce frequent conflicts between healthcare professionals providing paediatric end‐of‐life care. Acta Paediatrica. 2018;107(2):262–269. doi:10.1111/apa.14013

18. Oluyemi JA, Adejoke JA. Rivalry among health professionals in Nigeria: a tale of two giants. Int J Dev Manage Rev. 2020;15(1):343–352.

19. Goodman LA. Snowball sampling. Ann Math Statist. 1961;1:148–170. doi:10.1214/aoms/1177705148

20. Sedgwick P. Snowball sampling. BMJ. 2013;20:347.

21. Yates DS, David SM, Daren SS. The Practice of Statistics.

22. Sexton M, Orchard C. Understanding healthcare professionals’ self-efficacy to resolve interprofessional conflict. J Interprof Care. 2016;30(3):316–323. doi:10.3109/13561820.2016.1147021

23. Dixon J, Dewar S. The NHS plan: as good as it gets—make the most of it”. BMJ. 2000;321(7257):315–316. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7257.315

24. Badejo O, Sagay H, Abimbola S, Van Belle S. Confronting power in low places: historical analysis of medical dominance and role-boundary negotiation between health professions in Nigeria. BMJ Global Health. 2020;5(9):e003349. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003349

25. Regan S, Orchard C, Khalili H, Brunton L, Leslie K. Legislating interprofessional collaboration: a policy analysis of health professions regulatory legislation in Ontario, Canada. J Interprof Care. 2015;29(4):359–364. doi:10.3109/13561820.2014.1002907

26. Ham C, Clark JM, Spurgeon P, Dickinson H, Armit K. Medical chief executives in the NHS: facilitators and barriers to their career progress; 2010.

27. Warren OJ, Carnall R. Medical leadership: why it’s important, what is required, and how we develop it. Postgrad Med J. 2011;87(1023):27–32. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2009.093807

28. Alubo O, Hunduh V. Medical dominance and resistance in Nigeria’s health care system. Int J Health Serv. 2017;47(4):778–794. doi:10.1177/0020731416675981

29. Oleribe OO, Udofia D, Oladipo O, et al. Healthcare workers’ industrial action in Nigeria: a cross-sectional survey of Nigerian physicians. Hum Resour Health. 2018;16(1):54. doi:10.1186/s12960-018-0322-8

30. Osemwota O. Some Issues in Nigerian Health Planning and Management. Benin, Nigeria: Omega Publishers; 1992.

31. Oleribe OO. Management of Nigerian health care institutions: a cross sectional survey of selected health institutions in Abuja Nigeria. J Public Administr Policy Res. 2009;1(4):63–70.

32. Vyt A. Interprofessional and transdisciplinary teamwork in health care. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2008;24(S1):S106–S109. doi:10.1002/dmrr.835

33. Rosen MA, DiazGranados D, Dietz AS, et al. Teamwork in healthcare: key discoveries enabling safer, high-quality care. Am Psychologist. 2018;73(4):433. doi:10.1037/amp0000298

34. Harkins D, Butz D, Taheri P. A new prescription for healthcare leadership. J Trauma Nurs. 2006;13(3):126–130. doi:10.1097/00043860-200607000-00011

35. Yuin YS, Sze GW, Durganaudu H, Pillai N, Yap CG, Jahan NK. Review of leadership enhancement strategies in healthcare settings. Open Access Lib J. 2021;8(6):1–4.

36. Wang Y, Liu YF, Li H, Li T. Attitudes toward physician-nurse collaboration in pediatric workers and undergraduate medical/nursing students. Behav Neurol. 2015;2015:1.

37. Adigwe OP. Stakeholder’s perspective of role of policy and legislation in achieving medicines’ security. Int J World Policy Dev Stud. 2020;6(6):66–73. doi:10.32861/ijwpds.66.66.73

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.