Back to Journals » Risk Management and Healthcare Policy » Volume 15

Job Motivation and Satisfaction Among Female Pharmacists Working in Private Pharmacy Professional Sectors in Saudi Arabia

Authors Al-Omar HA , Khurshid F, Sayed SK, Alotaibi WH, Almutairi RM, Arafah AM, Mansy W , Alshathry S

Received 5 April 2022

Accepted for publication 12 July 2022

Published 21 July 2022 Volume 2022:15 Pages 1383—1394

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S369084

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Jongwha Chang

Hussain Abdulrahman Al-Omar,1 Fowad Khurshid,1 Sarah Khader Sayed,1 Wedad Hamoud Alotaibi,1 Rehab Mansour Almutairi,1 Azher Mustafa Arafah,1,2 Wael Mansy,1 Sultan Alshathry3

1Department of Clinical Pharmacy, College of Pharmacy, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; 2College of Pharmacy, Almaarefa University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; 3Ministry of Health, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence: Hussain Abdulrahman Al-Omar, Department of Clinical Pharmacy, College of Pharmacy, King Saud University, P.O. Box 2457, Riyadh Zip, 11451, Saudi Arabia, Tel +966- 11-4673637, Fax +966 − 11- 4677480, Email [email protected]

Background: Pharmacists’ job satisfaction has been of interest for many years and is of great importance in several respects, such as productivity and ultimately organizational performance.

Objective: This study aimed to investigate the perceived motivational factors and levels of job satisfaction of female pharmacists working in private pharmaceutical sectors.

Methods: This was a cross-sectional study using a web-based survey of randomly selected female pharmacists working in different private settings including community pharmacies, pharmaceutical companies, private hospitals, and other private sectors using a pre-validated satisfaction scale (Warr–Cook–Wall scale).

Results: A total of 232 female pharmacists participated in the study with a mean age of 26.1± 2.4 years. Of the total respondents, more than half (58%) worked for pharmaceutical companies, 25% worked in community pharmacies, and 16.8% were from hospital pharmacies. The most attractive motivating factors that encourage female pharmacists toward better performance were having the opportunity to learn new skills, being in contact with people both locally and internationally, gaining a sense of achievement, and being recognized, appreciated, and rewarded. The participants of this study were shown to have a moderate job satisfaction level.

Conclusion: This study revealed that the non-Saudi, part-time pharmacists who never expected a promotion were less satisfied than the Saudi, full-time employees who expected a promotion within a year.

Keywords: motivation, satisfaction, female, job, pharmacists, Saudi Arabia

Introduction

Job motivation and satisfaction are complex phenomena that have been of concern to behavioral scientists for many years. Job satisfaction is an individual’s emotional response to his or her current job condition, while motivation is the driving force to pursue and satisfy one’s needs. The two concepts are symbiotic in that the more an employee is invested in doing their job well, the happier they tend to be, and vice versa. The level of motivation that employees receive from their employers could correlate with their job satisfaction and turnover intention. High job satisfaction is directly tied to high motivation and vice versa.1,2 Increased job satisfaction, therefore, leads to a heightened sense of both personal and professional motivation, and likewise, strong motivation results in more satisfaction in a particular job. Unhappy employees have diminutive reason to help an organization to succeed and therefore display low motivation or interest in organizational goals.1,2 Behavioral theorists have linked job satisfaction to motivation and, consequently to productivity.3 It is desirable for managers to understand this construct4,5 as several studies have shown the vital relationship that links job satisfaction with motivation, which in turn has a major positive impact on productivity, innovation, and overall organizational performance.6–8 As would be expected, the reverse is true, too: having employees who are dissatisfied at work has negative consequences, such as increased rates of absenteeism, work fatigue, and burnout, decreased work quality and loyalty to the organization, and counterproductive work behavior, all of which leads to decreased turnover and additional cost.

Job satisfaction, which is expressed through positive behavior—it is called job dissatisfaction when expressed through negative behavior9—can be defined in different ways. According to Vroom, job satisfaction is “the positive orientation of an individual towards all aspect of the work”.10 Similarly, McCormick and Tiffin define it as “the total of [an employee’s] sentiments related [to] the job conducted”.11 If workers perceive that their values are realized, they adopt a positive attitude toward their job and become more satisfied. These different definitions of job satisfaction add to the complexity of examining it in the workplace.12

In their study, Seashore and Taber were able to divide the factors affecting job satisfaction as falling into two main categories: individual factors such as age, background, abilities and learning styles, mental stability including any transient personality traits, situational personality, perceptions, and expectations—and environmental factors such as political, economic, organizational, and job environments.13 Locke took a different approach, dividing influences on job satisfaction into events/conditions and agents.4 Other factors that have since been found to have a bearing on employees job satisfaction are the role itself, as well as the hours and workload involved; whether they have a good relationship with their manager; whether they are able to make decisions and work independently; whether they work in a pleasant setting or, where relevant, a safe one; how much they are paid and what benefits they get, including the amount of holiday they are entitled to each year; whether they have any chance of promotion; and whether their job is secure. Laurence Siegel suggested that a few more personal characteristics should be added, such as gender, level of intelligence, and ability to adapt.14 There are certainly factors here that organizations can improve; doing so will likely increase their employees’ morale and, consequently, their performance.

When it comes to pharmacy, both the scope of pharmacy as a profession and the primary role of the pharmacist have evolved a great deal. Part of this is pharmacy being actively promoted as a female-friendly, well-paid, higher-status career profession that is more compatible with family responsibilities than many other professions.15,16 In recent years, a growing number of female pharmacists have joined the wide-ranging private pharmacy profession, which is both rewarding and challenging.16 In Saudi Arabia, according to the 2020 healthcare professional taskforce census, there are 27,529 pharmacists, of whom 35.2% are Saudi. Among those are 4977 female pharmacists, 77.4% of whom are Saudi, with almost 52% of the total number of female pharmacists working in governmental healthcare sectors.17 In 2016, a directive was issued permitting private pharmacies in Saudi Arabia to employ Saudi female pharmacists.

Pharmacists’ job satisfaction has been of interest for many years and is of great importance in several respects. An examination of job satisfaction among female pharmacists is likely to take into account humanitarian factors such as whether they are treated fairly, honorably, and respectfully. High levels of job satisfaction could also be a sign of pharmacists’ mental and emotional wellness in addition to being able to boost organizational turnover and decrease absenteeism.9,18

Pharmacists cannot meet their jobs’ needs if their own needs are not met. This challenge puts pressure on organizations’ managers and leaders to take responsibility for employees’ satisfaction; managerial attitudes, especially those of upper managers, significantly affect employee satisfaction. Job satisfaction can be enhanced by attending to motivational factors such as making the work environment more attractive, requiring more initiative, and fostering creativity, innovation, and planning.9 Paying attention to job satisfaction is especially relevant when budget constraints limit increases to pay and benefits. Employees who feel valued are more likely to work harder toward furthering the organization’s aims;18 thus, understanding what motivates their employees will help organizations keep their staff loyal, committed, and high-performing.19 Equally true is that employees who do not feel satisfied or supported at work often lose faith in the organization and are more likely to argue with colleagues.20

Given that much of the limited published evidence about job satisfaction among female pharmacists in Saudi Arabia is out of date following recent policy and practice changes, it was considered time to revisit the subject to determine current levels of job satisfaction among female pharmacists. These women have not only experienced much upheaval of late but are also finding that their work has intensified. The present study has a threefold objective: to explore factors motivating the work patterns of females in private workplaces; to determine the level of job satisfaction among female pharmacists working in private pharmaceutical sectors; and to examine what relationship links female pharmacists’ socio-demographics with their workplace characteristics and job satisfaction.

Methods

Study Design

This cross-sectional study involved a self-administered online questionnaire, via Google Forms, that was made available to female pharmacists working in Saudi Arabia in various private workplaces including community pharmacies, pharmaceutical companies, private hospitals, and pharmaceutical industry. The study used convenience sampling to select participants based on availability and accessibility. Before the start of the study, each participant was informed about the purpose of the questionnaire and asked to complete and return it within 14 days. All participants were requested to sign and submit electronic informed consent prior to study commencement.

The questionnaire consisted of three main sections. The first section asked participants to answer items related to their sociodemographic, workplace, and job characteristics. Workplace and job characteristics are on the top list of the most crucial elements which can impact the level of satisfaction as well as motivation of organization employees including salary, working hours, workload, promotion, organizational structure and organization nature.21 The second section provided participants with a list of factors related to job motivation. The list was developed based on a literature review22–25 and sorted into five major groups: (1) workplace characteristics; (2) work conditions; (3) personal characteristics; (4) individual priorities; and (5) internal psychological states. The first two sections were multi-choice, with participants given a number of responses or ranges to choose from. The third section included items related to participants’ job satisfaction. It measured them using a pre-validated 16-item instrument, the Warr–Cook–Wall (W–C–W) scale, where each item is rated on a 7-point Likert scale, with a high score indicating a high level of item satisfaction.26 The W–C–W scale measures overall job satisfaction as well as satisfaction with certain aspects of work, including chances of promotion, amount of variety in the job, opportunity to use abilities, attention paid to the employee’s suggestions, freedom to choose work methods, relationship generally between managers and employees, and with immediate manager or director, colleagues, and fellow employees, amount of responsibility, workplace management style, physical work conditions, hours of work, remuneration, job security, recognition for work, and overall feeling about the job. In this section, participants were requested to choose their answers from options extremely satisfied, very satisfied, moderately satisfied, not sue, moderately dissatisfied, very dissatisfied, and extremely dissatisfied to reflect on their level of satistificantion on each statement of W–C–W scale.

Ethical Consideration

This study was approved by College of Pharmacy, Almaarefa University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia – college research committee with approval number MCST (AU)-COP 1902/RC.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics including frequency, percentage, inter-quartile range, mean, and standard deviation (SD) were calculated for the demographics, workplace characteristics, and job motivation factors, as well as for the W-C-W scale score. Associations between the demographic and workplace and job characteristics of the survey respondents and the W-C-W scale were examined in two stages. The first stage examined the separate association between each factor of participants, workplace and job characteristics and the summary score obtained from the W-C-W scale in a series of univariable analyses. The W-C-W score was found to be normally distributed. As a result, the unpaired t-test was used to compare between characteristics with only two categories. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for characteristics with three or more categories. The results from the first stage were presented in a table format as mean ±SD of W-C-W score in each category, with p-values, indicating the significance of the difference in scores between categories. The second stage of the analysis examined the joint association of the participants, workplace and job characteristics in a multivariable analysis. This has the advantage that the association between each factor and the outcome is adjusted for the other included factors. This stage of the analysis was performed using multiple linear regression. Only factors showing some association with the outcome from the initial analyses (p < 0.2) were included in this stage of the analysis. A backwards selection was performed to retain only the significant factors associated with the outcome in the final model. This involved omitting non-significant factors, one at a time, until all remaining factors were significant. The results from the second stage are presented in a table format as regression coefficients, along with corresponding confidence intervals. These represent the mean difference in W-C-W score between each category and a baseline category, with p-values, indicating the significance of the results.

In all analyses, response categories with small numbers were combined together with a similar category, where appropriate, in order to boost the numbers in each category and increase the statistical power of the analyses. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. The analysis was performed using IBM® SPSS® software Version 24.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corporation, 2016).

Results

A total of 232 female pharmacists participated in the study with a mean age of 26.1±2.4 years. Table 1 shows the sociodemographic, workplace and job characteristics of the participants. The data suggested that the majority of the respondents were Saudi (90.1%). More than three-quarters (80%) were single, and a higher percentage (88%) had no children. Fewer than 10% had a graduate degree. Of the total respondents, more than half (58%) worked for pharmaceutical companies, 25% worked in community pharmacies, and 16.8% were from hospital pharmacies. The median time with the current employer was 12 months overall, with a median of 10 months in their current position. Around 80% of respondents earned 15,000 Saudi Riyals per month or lower. The majority of staff (95%) held full-time positions.

|

Table 1 Sociodemographic Characteristics of Study Participants |

Factors Affecting Work Motivation

The factors affecting female pharmacists’ work motivation were divided into five categories: (1) workplace characteristics; (2) working conditions; (3) personal characteristics; (4) individual priorities; and (5) internal psychological state (Table 2). Questionnaire responses related to factors influencing female pharmacists’ job motivation are presented in “Supplementary Table 1”.

|

Table 2 Factors Influencing Job Motivation of Female Pharmacists |

Considering workplace and job characteristics, female pharmacists were motivated by recognition, appreciation, and reward (88.8%), job accessibility (87.1%), work location (83.6%), and opportunity for continuous training (83.2%). In term of working condition, female pharmacists’ work motivation was affected by contact with people locally and internationally (90.5%), job opportunity (88.8%), independence/flexibility in the job (85.8%), and career advancement and promotion opportunities (84.9%). In view of personal characteristics, it was noticed that the desires for gainful employment (88.8%), respect (88.8%), and skills, competencies, and abilities (88.4%) were related to the work motivation of female pharmacists’ employed in the private sector. As individual priority, female pharmacists appeared to be motivated if their work met certain individual needs and values that were important to them, including the opportunity to learn new skills (93.5%), enhanced social status (88.8%), the opportunity to test ideas in work (82.8%), and the ability to generate income to secure their future financially (82.8%). By way of internal psychological state, gaining a sense of achievement (89.2%), and furthering their career (88.8%) all affected their work motivation (Table 2).

Job Satisfaction

The W-C-W scale results suggest that female pharmacists in general had moderate levels of job satisfaction. Overall, the mean total score was 74 [SD: ± 27.7; range = 16-112]. Female pharmacists derive the highest satisfaction from their colleagues, from having attention paid to their suggestions, from having opportunities to use their abilities, from enjoying good relationships with their managers and co-workers, and from being given a good amount of responsibility (Table 3).

|

Table 3 Responses of Female Pharmacists on Warr–Cook–Wall Satisfaction Scale |

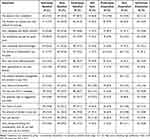

Associations Between Respondent, Workplace, and Job Characteristics and W-C-W scores—univariable Analyses

Table 4 summarizes the results of the univariable analyses. The results suggest that the majority of respondent characteristics were not significantly associated with the W-C-W scores. However, some significant associations were observed. Significant results were found for nationality (p = 0.03), employment status (p = 0.002), and when the next promotion was expected (p = 0.002). There was also some evidence of a difference in scores among different workplace settings, although this result was only of borderline statistical significance. There were only a relatively small number of non-Saudi in the sample; however, these had lower W-C-W scores than Saudi, on average. The mean score was 75 for Saudi, but only 62 for non-Saudi. Part-time workers were also small in number; however, these had substantially lower scores than their full-time equivalents. The mean value for part-time workers was 51, compared to 75 for full-time workers. There was little difference in scores between those who expected a promotion within a year and those who considered they would have to wait more than a year. However, the small group who did not expect any promotion at any time had much lower scores. The mean value of the W-C-W for this group was 50, compared to 77 and 75 for the other two groups.

|

Table 4 Associations Between Respondent, Workplace, and Job Characteristics and Warr-Cook-Wall Score (Univariable Analyses) |

Associations Between Respondent, Workplace, and Job Characteristics and W-C-W scores—multivariable Analysis

A multivariable analysis of the respondent, workplace, and job characteristics and the W-C-W scores is shown in Table 5. The results suggested some evidence that the province in which the participants worked, their employment status, and when they next expected a promotion were associated with the W-C-W score. The result for the province worked was only of borderline statistical significance, but it was chosen to retain this variable in the final model. After adjusting for these three variables, there was no significant additional effect of nationality, which was found to be significant in the initial analyses. As in the univariable analyses, part-time workers had significantly lower scores. After adjusting for the other factors, these were, on average, 22 units lower than scores for full-time workers. The results for the next promotion were also similar to those observed previously. Those who never expected a promotion also had the lowest scores. The scores for this group were, on average, 26 units lower than for respondents who expected a promotion within a year. Respondents in the Western and Central regions had the highest scores, with lower values in the Eastern, Northern, and Southern regions.

|

Table 5 Associations Between Respondent, Workplace, and Job Characteristics and Warr-Cook-Wall Score (Multivariable Analyses) |

Discussion

Job motivation and satisfaction have been extensively studied in various contexts, but investigation into female employees has always been poor. As a step toward filling this void, this paper reports the results of a cross-sectional study that investigated the motivational factors and assessed the levels of job satisfaction of female pharmacists working in private pharmaceutical sectors. To the authors’ knowledge, this study is among the first to explore female pharmacists’ job motivation and satisfaction in the private sector in Saudi Arabia.

Any job—and the performance of it—can be optimized by reducing its negative aspects and boosting its positive ones, and understanding the impact of job motivation and satisfaction is a crucial part of achieving this. Supporting employees to feel driven and inspired in their jobs makes for a more productive and loyal workforce and higher turnover. Furthermore, identifying the influencing factors and maintaining job satisfaction in the workplace can have a significant effect on staff retention and their ability and willingness to provide appropriate care. Likewise, as shown in a cross-sector study of pharmacists in Saudi Arabia, measuring, analyzing, and improving employees’ engagement at work can help organizations to foster motivation, productivity, and retention.27

The results of the present study show that the motivational factors most likely to encourage female pharmacists to perform better were opportunity to learn new skills and being able to interact and communicate with experts both locally and internationally. Nowadays, there is much more of a culture of workforces regularly undertaking new training and learning.28 Being able to assimilate new skills has become essential for advancing in almost any career; the more competencies an employee has, the more likely they are to be promoted and to earn a higher salary. Someone who is highly motivated at work is always on the lookout for opportunities to develop their talents and become more valuable as an employee; from the opposite viewpoint, employers tend to give more in terms of promotion and other rewards to employees who demonstrate this kind of initiative and commitment to both the job and the organization.

Other important motivational factors for female pharmacists revealed by this study were gaining a sense of achievement, recognition, and fulfillment;29 being offered job opportunities; being recognized, appreciated, and rewarded; enjoying enhanced social status; being gainfully employed; being respected; and having opportunities to add something to their career.

Findings from this study indicated that responding pharmacists who worked in different settings had a moderate level of job satisfaction. These findings are consistent with those of previously published research.30–33 However, this finding could also be attributed to female employees’ lower job expectations. One study showed that women have lower expectations than men about employment outcomes, so their goals are fulfilled more easily.34

In the regression model, the significant determinants of job satisfaction were nationality, employment status, and timing of likely next promotion. The study revealed that Saudi female pharmacists were more satisfied than their non-Saudi counterparts. The differences denote the possible existence of wage disparity among Saudi and non-Saudi pharmacists as the salaries offered by firms to non-Saudi pharmacists are lower than those received by Saudi pharmacists.35

Job dissatisfaction impacts job performance, resulting in an increased number of work mistakes and stress.36 Likewise, our findings show that part-time female pharmacists were less satisfied with their jobs than full-time workers, and this low satisfaction level was possibly because of low pay/compensation and/or fewer promotion opportunities. The results of this study are consistent with the findings of some previous studies.37,38

Promotions are an important aspect of a pharmacist’s career. This study found that participants who expected to be promoted within the upcoming year were much satisfied at work than those who felt certain that they would never be promoted; in fact, it was found to be one of the biggest influences on job satisfaction.39 Pharmacists who earned less and/or felt that they were not promoted enough were not satisfied with their jobs and, consequently, demonstrated higher professional negligence. Another cross-sectional survey that was carried out among pharmacists to measure perceptions of job satisfaction reported fewer promotion opportunities (42%) as one of the main reasons for poor job satisfaction.40

As with all studies, this one had some limitations. First, the convenience sampling, selecting only participants who were available, restricted the generalizability of the results. Second, the participants were mostly young females working in the private pharmaceutical sector—this also limited the generalizability of the results by not including more senior-level female pharmacists and those working in other settings. Third, the lack of similar researches on this subject have limited comparison being made.

Conclusion

According to the study results, the main factors that motivate female pharmacists to perform better at work were being able to learn new skills; feeling that they were achieving something; getting promoted; and being recognized, appreciated, and rewarded. Our findings indicate different levels of job satisfaction among female pharmacists of different nationality (Saudi vs non-Saudi), employment status (full-time vs part-time), and promotion expectation (next promotion expected). The participating female pharmacists were shown to have moderate job satisfaction. We found that non-Saudi female pharmacists, part-time employees, and those who never expected a promotion were less satisfied than those who were full-time, Saudi employees who expected a promotion within a year. These findings are important for pharmaceutical firms’ leaders as they will enable them to focus on policies, management, and environmental issues, with the purpose of increasing the level of satisfaction among their employees. Future studies are needed to explore the motivation and satisfaction of female pharmacists with a wider range of participants and more indicators of motivation and job satisfaction, and to identify the underlying reasons for job dissatisfaction, so that appropriate strategies can be adopted to improve the situation.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from any funding agencies in the public, commercial or nonprofit sectors.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Pleşa R. Relationship between motivation, satisfaction and performance in work. Ann Univ Petrosani Economics. 2019;19(2):119–124.

2. Rožman M, Treven S, Čančer V. Motivation and satisfaction of employees in the workplace. Bus Syst Res. 2017;8(2):14–25. doi:10.1515/bsrj-2017-0013

3. Likert R, Katz D. Supervisory Practices and Organizational Structures as They Affect Employee Productivity and Morale. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Organizational Behavior, Prentice-Hall, Inc; 1979:56–57.

4. Locke EA. The nature and cause of job satisfaction. In: Dunnette MD, editor. Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Chicago: Rand Mc Nally; 1976.

5. Herzberg F, Mausner B, Snyderman BB. The Motivation to Work. Transaction Publishers; 2010.

6. Aziri B. Job satisfaction: a literature review. Manag Res Pract. 2011;3(4):77–86.

7. de Oliveira Vasconcelos Filho P, de Souza MR, Elias PE, D’Avila Viana AL. Physicians’ job satisfaction and motivation in a public academic hospital. Hum Resour Health. 2016;14(1):75. doi:10.1186/s12960-016-0169-9

8. Kitsios F, Kamariotou M. Job satisfaction behind motivation: an empirical study in public health workers. Heliyon. 2021;7(4):e06857. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06857

9. Mishra L. Job satisfaction: a comparative analysis. Int Soc Sci J. 2013;29(2):283–295.

10. Vroom VH. Work and Motivation. Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1995.

11. McCormick EJ, Tiffin J. Industrial Psychology. Prentice-Hall; 1974.

12. Weiss HM. Deconstructing job satisfaction. Hum Resour Manag Rev. 2002;12(2):173–194. doi:10.1016/S1053-4822(02)00045-1

13. Seashore SE, Taber TD. Job-satisfaction indicators and their correlates. Am Behav Sci. 1975;18(3):333–368. doi:10.1177/000276427501800303

14. Siegel L. Industrial Psychology. R.D. Irwin; 1969.

15. Janzen D, Fitzpatrick K, Jensen K, Suveges L. Women in pharmacy: a preliminary study of the attitudes and beliefs of pharmacy students. Can Pharm J. 2013;146(2):109–116. doi:10.1177/1715163513481323

16. Youdovin S, Eldridge H, Maher A, Madell R. The POWER Study Pharmaceutical Company Climate for Women; 1999.

17. Statistical Yearbook 2020 Chapter II: health Resources. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/Statistics/book/Documents/Chapter_2_2020.xlsx.

18. Spector PE. Job Satisfaction: Application, Assessment, Causes, and Consequences. Vol. 3. Sage; 1997.

19. Rhoades L, Eisenberger R. Perceived organizational support: a review of the literature. J Appl Psychol. 2002;87(4):698–714. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.698

20. Bobbio A, Bellan M, Manganelli AM. Empowering leadership, perceived organizational support, trust, and job burnout for nurses: a study in an Italian general hospital. Health Care Manage Rev. 2012;37(1):77–87. doi:10.1097/HMR.0b013e31822242b2

21. Raziq A, Maulabakhsh R. Impact of working environment on job satisfaction. Procedia Econ Financ. 2015;23:717–725. doi:10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00524-9

22. Toode K, Routasalo P, Suominen T. Work motivation of nurses: a literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48(2):246–257. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.09.013

23. Jamieson I, Kirk R, Wright S, Andrew C. Generation Y New Zealand registered nurses’ views about nursing work: a survey of motivation and maintenance factors. Nurs Open. 2015;2(2):49–61. doi:10.1002/nop2.16

24. Benslimane N, Khalifa M. Evaluating pharmacists’ motivation and job satisfaction factors in Saudi hospitals. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2016;226:201–204.

25. Perreira TA, Innis J, Berta W. Work motivation in health care: a scoping literature review. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2016;14(4):175–182. doi:10.1097/XEB.0000000000000093

26. Hassell K, Seston E, Shann P. Measuring job satisfaction of UK pharmacists: a pilot study. Int J Pharm Pract. 2007;15(4):259–264. doi:10.1211/ijpp.15.4.0002

27. Al-Omar HA, Arafah AM, Barakat JM, Almutairi RD, Khurshid F, Alsultan MS. The impact of perceived organizational support and resilience on pharmacists’ engagement in their stressful and competitive workplaces in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm J. 2019;27(7):1044–1052. doi:10.1016/j.jsps.2019.08.007

28. Shkoler O, Kimura T. How does work motivation impact employees’ investment at work and their job engagement? A moderated-moderation perspective through an international lens. Front Psychol. 2020;11:38. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00038

29. Franco LM, Bennett S, Kanfer R. Health sector reform and public sector health worker motivation: a conceptual framework. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54(8):1255–1266. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00094-6

30. Carvajal MJ, Popovici I. Gender, age, and pharmacists’ job satisfaction. Pharm Pract. 2018;16(4):1396. doi:10.18549/PharmPract.2018.04.1396

31. Carvajal MJ, Popovici I, Hardigan PC. Gender differences in the measurement of pharmacists’ job satisfaction. Hum Resour Health. 2018;16(1):33. doi:10.1186/s12960-018-0297-5

32. Carvajal MJ, Popovici I, Hardigan PC. Gender and age variations in pharmacists’ job satisfaction in the United States. Pharmacy. 2019;7(2). doi:10.3390/pharmacy7020046

33. Mattsson S, Gustafsson M. Job satisfaction among Swedish pharmacists. Pharmacy. 2020;8(3). doi:10.3390/pharmacy8030127

34. Clark AE. Job satisfaction and gender: why are women so happy at work? Labour Econ. 1997;4(4):341–372. doi:10.1016/S0927-5371(97)00010-9

35. Suleiman AK. Stress and job satisfaction among pharmacists in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Med Med Sci. 2015;3(3):213–219. doi:10.4103/1658-631X.162025

36. Al Khalidi D, Wazaify M. Assessment of pharmacists’ job satisfaction and job related stress in Amman. Int J Clin Pharm. 2013;35(5):821–828. doi:10.1007/s11096-013-9815-7

37. Ibrahim IR, Ibrahim MI, Majeed IA, Alkhafaje Z. Assessment of job satisfaction among community pharmacists in Baghdad, Iraq: a cross-sectional study. Pharm Pract. 2021;19(1):2190. doi:10.18549/PharmPract.2021.1.2190

38. Belay YB. Job satisfaction among community pharmacy professionals in Mekelle city, Northern Ethiopia. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2016;7:527–531. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S116147

39. Slimane NSB. Motivation and job satisfaction of pharmacists in four hospitals in Saudi Arabia. J Health Manag. 2017;19(1):39–72. doi:10.1177/0972063416682559

40. Ahmad A, Patel I. Job satisfaction among Indian pharmacists. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2013;5(4):326. doi:10.4103/0975-7406.120069

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.