Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

How Parasocial Relationship and Influencer-Product Congruence Shape Audience’s Attitude Towards Product Placement in Online Videos: The Mediation Role of Reactance

Received 31 January 2023

Accepted for publication 14 April 2023

Published 20 April 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 1315—1329

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S406558

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Mei-Chun Cheung

Yuetong Du,1 Jian Raymond Rui,1 Nan Yu2

1Department of New Media and Communication, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, Guangdong Province, People’s Republic of China; 2Nicolson School of Communication and Media, University of Central Florida, Orlando, FL, USA

Correspondence: Jian Raymond Rui, Tel +86 178 1972 0631, Email [email protected]

Introduction: Social media enable advertisers to promote products by placing ads into videos posted by social media influencers. However, according to psychological reactance theory, any persuasive attempt may evoke reactance. Therefore, how to minimize the audience’s potential resistance to product placements is important. This study investigated how the parasocial relationship (PSR) between audiences and influencers as well as the extent to which the influencer’s expertise matched the product (termed as influencer-product congruence) shaped audience attitude towards the product placement and their purchase intention through reactance.

Methods: The study conducted a 2 (PSR: high vs low) × 2 (influencer-product congruence: congruent vs incongruent) between-subjects online experiment (N = 210) to test hypotheses. SPSS 24 and PROCESS macro by Hayes were used to analyze the data.

Results: The results demonstrate that PSR and influencer-product congruence enhanced the audience’s attitude and purchase intention. Moreover, these positive effects were mediated by lowering levels of the audience’s reactance. Additionally, we found preliminary evidence suggesting that PSR moderated the effect of perceived expertise of the influencer on reactance. Specifically, this effect was stronger among those reporting a low level of PSR compared to a high level.

Conclusion: Our findings reveal how PSR and influencer-product congruence are intertwined to shape audience evaluation of product placement via social media and highlight the central role of reactance in this process. This study also provides advice on the selection of influencer when promoting product placement on social media.

Keywords: product placement, psychological reactance, parasocial relationship, match-up hypothesis, influencer marketing

Introduction

Social media enable advertisers to place ads in the videos created by social media influencers. These influencers are usually considered amateur, so they tend to be perceived as more credible and engage more with users online.1 Additionally, most influencers charge less for advertising than professional media.2 Thus, online videos posted by influencers have become an appealing option for advertisers.

While studies explored the factors or strategies that boost the persuasive effect of product placement in online videos from a positive perspective,3 we need to be wary of its potential backfire effect. Given the persuasive nature of product placement, it has the potential to trigger the audience’s reactance due to their perceived threat to freedom,4–7 which may cause rejection and negative evaluations of the product. Therefore, how to minimize audience reactance is essential to product placements.

Influencers differ from traditional professional media agencies as the new source for product placement in two following ways. First, the interactivity of social media makes it possible to facilitate the parasocial relationship (PSR) between the influencer and the audience. PSR was found to enhance audiences’ evaluations of products or brands8–10 and has the potential to mitigate reactance as it was proven to be associated with the recipients’ lower perception of persuasive and controlling intention,11–13 sales attempt14 and other outcomes related to reactance. Second, unlike mass media production providing content with diverse backgrounds, social media influencers usually have expertise within only one or several domains. According to the match-up hypothesis, when there is an incongruence between the product and the influencer’s characteristics, it could lead to a decline in the audience’s attitude,15,16 or lead to an attribution of the influencer’s recommendation to a persuasion-based financial gain which is potentially related to reactance.14,15

Most studies that discussed the impact of reactance on social media product placement were conducted in Western countries with individualistic cultures.5,8,17,18 However, cross-cultural studies contended that consumers in countries with collectivistic cultures were less likely to evoke reactance towards persuasion.19–21 Therefore, the present study would be conducted with Bilibili, one of the biggest video-sharing platforms in China, to explore whether psychological reactance still plays an important role in shaping the audience’s attitude towards product placement in a country with collectivistic culture. Moreover, prior research explored the negative effect of the product placement posted by social media influencers from a content-oriented perspective (eg, prominence or disclosure of the product placement),5,16,18,22,23 but the new source features of influencers, compared to the traditional media, received little attention, and this would be the focus of our research.

Through an online experiment in China, we examined how PSR and influencer-product congruence played an important role in enhancing the audience’s response to the product placement videos via lowering their reactance. The results of this study provide empirical evidence that reactance can powerfully influence persuasion outcomes and reveal the theoretical relations between PSR, match-up hypothesis, and psychological reactance theory. Practically, this study provides possible solutions for brands on how to hedge the risk of product placement failures through proper influencer selection.

Literature Review

Psychological Reactance and Product Placement

Brehm24 posited that when individuals think their freedom is threatened, they may feel motivated to reestablish their freedom, termed as reactance.24–26 Reactance can lead to various freedom restoration acts and eventually cause the failure of persuasion.26,27 Therefore, reducing consumers’ reactance to advertisements is important, especially when they are considered as forced exposure like pop-up advertisement and product placements.8,28,29

Reactance can be closely related to product placements.30,31 Balasubramania32 defined product placement as

A paid product message aimed at influencing movie (or television) audiences via the planned and unobtrusive entry of a branded product into a movie (or television program). (p. 31)

Subsequent research has investigated this concept in other media contexts.33–35 When product placements are integrated into media programs, audience’s freedom to choose whether to view the advertisement is restricted, which may evoke reactance.

Research noted that reactance can shape audience attitudes, responses and behaviors towards product placement. For instance, Chang30 found that for those with a high level of reactance, exposure to an episode with a higher level of brand saturation was less likely to cause product purchase. Boerman et al23 suggested that longer sponsor disclosures led to higher levels of attitudinal persuasion knowledge, which caused the audience’s reactance and subsequently a worse brand attitude. Although how reactance affects the persuasive effect of product placement has rarely been discussed in new media, a few studies still provided insights. For example, Carlitz18 found that reactance mediated the relationship between online video advertisement placement and advertisement avoidance. Hence, video advertisement placement can trigger reactance, perhaps because audience thinks their freedom of media use is limited.

Given the negative effect of reactance on audience attitude towards product placement, it is necessary to examine how to mitigate reactance. Previous research has discussed the factors that influence psychological reactance to advertisements.8,31 However, as argued earlier, the heightened level of interactions between social media influencers and their followers and the lack of diversity of expertise provide a unique opportunity to examine what factors may affect reactance of product placement via social media.

Additionally, prior research that tested the negative effect of psychological reactance on advertisement, especially product placement and other types of forced exposure advertisement,8,18,23,28,29 were mostly conducted in western countries with individualistic culture (eg, the United States and the Netherlands). By contrast, collectivistic cultural context was less included. However, some cross-cultural studies contend that consumers in countries with collectivistic cultures like China and South Korea are less likely to be influenced by their perceived threat to freedom and experience reactance towards advertisement,19–21 since collectivistic cultures do not encourage autonomy, freedom and independence as much as individualistic cultures. For example, research revealed that East Asian consumers showed lower levels of reactance to the advertisement that contained freedom-threatening elements than consumers in Western countries.21 Moreover, Kim et al20 found that while American consumers had a stronger perceived threat to freedom for assertive information than for nonassertive information, there was no significant difference in Korean consumers’ perceptions of the two types of information. However, research findings are inconsistent, since Quick and Kim36 contended that even in a collectivist country (ie, South Korea), people also perceived the threat to freedom and thus a psychological reactance to the advertisement that used controlling language. The present study seeks to examine if psychological reactance plays a key role in influencing persuasive effect during product placement in China, a country with collectivistic culture.

PSR

The audience on user-generated content platforms like YouTube and Bilibili may have established a strong virtual relationship with the influencer.9 Previous research has termed this seemingly face-to-face or interpersonal unilateral relationship between audience and media characters as PSR.9,37 Horton and Wohl37 argued that PSR functions similarly to interpersonal relationships and forms through an illusion of interactions with media characters,38 making the audience develop an intimacy with these characters.39

User-generated content platforms provide many opportunities which may facilitate PSR development. Followers can interact with influencers by commenting on, “liking” their videos and even receiving feedback from influencers. Furthermore, influencers usually present themselves as ordinary individuals and make themselves approachable to followers by sharing their personal life. Hence, audience may think that they have developed friendships with these influencers.40

Empirical research has offered volumes of evidence on the power of PSR. For example, Hwang and Zhang9 demonstrated that PSR enhanced both the audience’s purchase intention and online word-of-mouth. Likewise, Torres and colleagues16 found that the more followers liked and were familiar with the influencer, the more credible they perceived the influencer’s recommendations.

The present study operationalized audience evaluations of product placement as their attitudes and their purchase intention. Based on the positive relationship between PSR and persuasive effect in previous research, the first set of hypotheses were raised as follows.

H1: The PSR between audience and influencer positively predicts audience’s (a) attitude towards the product placement and (b) purchase intention.

Moreover, the relationships raised in H1 might occur through a reduced level of reactance. People are usually less vigilant to those who are closer to them. As Tukachinsky and Sangalang41 found, when the audience had a distant PSR with the media character, the interaction during media exposure increased the degree of reactance to the media message. Moyer-Gusé and her colleagues found that as PSR became closer, audiences perceived lower levels of persuasive and controlling intention from influencers, thereby reporting lower levels of reactance.11–13 Thus, PSR changes audience interpretation of the recommendation of social media influencers by minimizing negative connotations related to these recommendations. Hence,

H2: Audience’s reactance to the product placement video mediates the positive effect of the PSR between audience and influencer on the audience’s (a) attitude towards the product placement and (b) purchase intention. Specifically, PSR exhibits a negative effect on audience reactance, which predicts a positive effect on their (a) attitude towards the product placement and (b) purchase intention.

The Match-Up Hypothesis

The match-up hypothesis posits that the endorsement is perceived more effective when they match the advertised products.15,42,43 Prior research has discussed the “match-up” effect between products and various features of media characters, including endorsers’ appearance features like attractiveness or their personal style,42,44 the endorser’s expertise on the type of product,43 and the advertisement character’s identity.45 The present study focuses on the expertise dimension of the match-up between influencers and products.

Since influencers tend to post videos on one or a few given topics, audience may naturally associate their expertise with these domains. Thus, audience may expect their endorsed products to be in these fields as well.46,47 Recent studies revealed that when the influencer’s characteristics matched the product, the audience exhibited more interest, more positive attitude and higher purchase intention towards the advertisement or the product.15,16,46,47 Therefore,

H3: Product placement video with higher levels of influencer-product congruence generate (a) better attitude towards the product placement and (b) higher purchase intention than the product placement video with lower levels of influencer-product congruence.

Attribution theory suggests that individuals may infer the causes of a behavior and develop attitudes, feelings, and actions towards the behavior based on their perceptions of the causes.48 According to the attribution theory, when the product matches the influencers’ expertise, the audience may believe that the recommendation is motivated by their sincere approval of the product.14,15 Conversely, when the influencer is promoting a product that seems irrelevant to his/her domain, audiences may consider the influencer’s recommendation is motivated by financial incentives.14 In this case, audiences might think the influencer is trying to benefit him/herself by shaping followers’ attitudes towards the product.

Psychological reactance theory contends that any persuasive intent may evoke a motivation to reject the advocacy.26 As the influencer-product incongruence may lead the audience to attribute their product promotion to financial benefits and thus perceive a strong advertising intent, we can speculate that reactance may be triggered by influencer-product incongruence, which can cause negative evaluations toward the product and the advertisement. Hence,

H4: Audience’s reactance to the product placement video mediates the effect of influencer-product congruence on the audience’s (a) attitude towards the product placement and (b) purchase intention. Specifically, the level of influencer-product congruence exhibits a negative effect on reactance, which then enhances their (a) attitude towards the product placement and (b) purchase intention.

Finally, the potential interaction effect between PSR and influencer-product congruence also merits discussions. As previous research stated, PSR may enhance the audience’s evaluation of source credibility,49 trustworthiness,50 product interest,51 and can lower the audience’s resistance towards the persuasion message.50 Hence, if the audience already establishes a close PSR with the influencer, they may naturally trust the influencer more. Moreover, Breves et al15 revealed that the PSR could weaken the impact of influencer-brand fit by an experiment. Thus, if the PSR between the audience and the influencer is closer, no matter whether the influencer endorses a product that matches or mismatches their expertise, the audience may always hold a positive attitude towards the product placement. By contrast, if the PSR between the audience and the influencer is more distant, the audience might leverage the cues of influencer-product congruence to evaluate the expertise of the influencer, which may affect their attitude towards the product placement. Therefore,

H5: The PSR between audience and influencer moderates the effect of influencer-product congruence on the audience’s (a) attitude towards the product placement and (b) purchase intention. Specifically, when the audience exhibits a high level of PSR with the influencer, influencer-product congruence has no significant effect on the audience’s (a) attitude and (b) purchase intention. Yet when the audience exhibits a low level of PSR with the influencer, influencer-product congruence has a positive effect on the audience’s (a) attitude and (b) purchase intention.

As mentioned earlier, when audiences feel the influencer is recommending a product that does not match his/her expertise, they might attribute this recommendation to financial incentives and perceive persuasive intent,14 which could evoke reactance. However, this negative impact due to the knowledge of persuasive intent also has the potential to be mitigated by a close PSR. Boerman and van Reijmersdal52 found that the negative indirect influence of sponsor disclosure on brand attitude via the selling intent perception disappeared among those children who experienced a close PSR with the YouTuber. Hence, we expect that a high level of PSR may counteract the reactance caused by the mismatch between influencers and products, which then predicted audience’s attitude and purchase intention. A moderated mediation hypothesis was thereby proposed.

H6: The PSR between audience and influencer moderates the mediations between influencer-product congruence and the audience’s (a) attitude towards the product placement and (b) purchase intention via psychological reactance. Specifically, the proposed mediation effects are only significant when the audience exhibits a low level of PSR with the influencer.

Method

Procedure

An online experiment was conducted to test all the research hypotheses in this study. The experiment employed a 2 (the level of PSR: high vs low) × 2 (influencer-product congruence: congruent vs incongruent) between-subjects factorial design. Two well-known food influencers on Bilibili and their videos involving product placement content were selected as the experimental stimuli. To minimize the potential influence of confounding variables derived from the experiment design, we chose two similar food influencers. They are both females, appear solo, and the majority of their videos were cooking tutorials. We selected two videos from each influencer. One video featured food-related product, whereas the product featured in the other video was not food (skincare product and digital product). To manipulate the level of PSR, we randomly asked participants to choose the influencer they liked/disliked from the two selected influencers, representing high/low level of PSR. We also manipulated the influencer-product congruence by randomly assigning participants to watch a video involving food-related or non-food-related product placement. After watching the video, participants were asked to complete a questionnaire.

Ethics Statement

This study received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee at College of Journalism and Communication, South China University of Technology. Participants were first exposed to the information sheet which informed them of the aim, procedure, benefits and risks of this study. They indicated their consent to participate in the study by clicking the “agree” button to proceed to the experiment stimulus and the survey.

Sample

A total of 244 students from a large university in South China participated in the experiment. All the participants were recruited from the campus WeChat groups. They must know the two influencers we mentioned. After respondents indicated their consent to participate, they were directed to the webpage of the questionnaire. Attention check questions were set to test the validity of the responses, and responses that failed the test were excluded. This led to a final sample of 210.

There were more females (58.6%) than males (41.4%). The frequency of grade distribution was listed as follows: freshman (20.0%), sophomore (19.5%), junior (26.2%), senior (17.6%), and graduate student (16.7%). Most participants (72.4%) reported as urban residents and 27.6% reported as rural residents. More than half of the students (58.1%) reported a monthly income (or living expenses) of 1001–2000 CNY, followed by 22.9% for 2001–3000 CNY, 10.0% for less than 1000 CNY, 5.2% for more than 4000 CNY, and 3.8% for 3001–4000 CNY.

We also measured participants’ daily time spent on Bilibili. Most participants reported they used more than 30 minutes per day to watch videos on Bilibili, specifically, with 39.0% reporting an average of 31–60 minutes per day, 23.8% for 61–90 minutes, 5.2% for 91–120 minutes, and 8.6% for more than 120 minutes. Only 23.3% of participants reported that they spent less than 30 minutes a day watching videos on Bilibili. Therefore, the general sample had a high involvement with Bilibili.

Measures

The operationalization of psychological reactance proposed by Dillard and Shen26 has been widely used in the past research, especially in health communication research.53 However, their measurement of anger described the emotion as “irritated, angry, annoyed, and aggravated” (p. 153), which could be too intense for small-value product recommendations such as food, skincare and digital products. Therefore, given the similarity of the research contexts, this study adapted a reactance scale by Bleier and Eisenbeis,54 which focuses on online advertisements. A 7-item Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) was used to measure the participants’ psychological reactance to the product placement video. Items included, “the product placement in the video disturbs me from watching the video/ I feel that the product placement in the video is trying to interfere with my freedom to purchase/ I find it intrusive to place product advertisement in the video/ placing product in the video is like forcing product information upon me/ product placement is unwelcomed/ I resist the product placement in this video/ I would like to dismiss or skip the part containing the product placement content when watching the video” (Cronbach’s α = .93, M = 3.96, SD = 1.31).

Participants’ attitude toward the product placement was assessed by a scale adapted from the scale testing consumer attitude toward social network advertising.55 A 4-item Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) was used to measure the attitude toward the product placement “(I find the product placement content in the video pleasant/ I find this kind of product placement enjoyable/ my general opinion about this kind of product placement is favorable/ I am positive toward the product placement in the video”; Cronbach’s α = .92, M = 4.58, SD = 1.37).

Based on a study about social media effects on user’s purchase intention,10 a 4-item Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) was adapted to measure the audience’s purchase intention for the product placed in the video. Items included, “after watching the video, I am interested in buying the product that was mentioned in the video/ I expect to buy the product similar to the influencer in her video/ I’d like to buy the product similar to the influencer in her video/ I plan to buy the product similar to the influencer in her video” (Cronbach’s α = .94, M = 3.22, SD = 1.30).

We also measured participants’ levels of PSR and influencer’s expertise for manipulation checks. The scale developed by Rubin and Perse56 is the most frequently used measurement of PSR.39 However, it was designed to measure PSR through traditional mass media, so we modified the wording to fit the context of the present research. In addition, since the scale by Rubin and Perse56 primarily measured the audience’s PSR with soap opera characters, the present study also included two items from a scale by Kim and colleagues10 reflecting the audience’s PSR with social media influencer. The final scale included 12 items (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Sample items included “the influencer in the video makes me feel comfortable, as if I am with a friend”, “I look forward to watching the video updated by this influencer”, “I would like to meet this influencer in person”, “I think the video content posted by this influencer is helpful for my interest in a certain area” (Cronbach’s α = 0.94, M = 4.52, SD = 1.06). Considering the measurement of PSR integrated items from two established research, we tested the construct validity of this scale, which demonstrated satisfactory results, χ2/df = 1.84, TLI = 0.97, CFI = 0.09, RMSEA = 0.06.

Till and Busler43 operationalized the congruence between media characters and products as the character’s perceived expertise regarding the type of products they endorsed. Following Till and Busler43 this study modified a semantic differential scale by Ohanian57 to test influencer’s perceived expertise. Expertise was measured with three 7-point semantic differential items included “as a food influencer, regarding to the product she recommended in the video, she is/is not an expert, experienced/inexperience, knowledgeable/unknowledgeable” (Cronbach’s α = 0.94, M = 4.00, SD = 1.47).

Results

Manipulation Checks

The manipulations of PSR and influencer-product congruence were checked prior to the data analysis. The result of independent-sample t tests showed that the level of PSR was successfully manipulated (M high PSR= 4.91, M low PSR= 4.11; t (208) = −6.19, p < 0.001). The manipulation of the influencer-product congruence was also successful (M high congruence= 5.03, M low congruence = 2.96; t (208) = −14.32, p < 0.001).

Main Effects of PSR, Influencer-Product Congruence and Their Interactions (H1, H3, and H5)

A multivariate analysis of variances (MANOVA) was conducted to test H1, H3, and H5. The result indicated the significant main effects of PSR (Wilks’ λ = 0.95, F (2, 205) = 5.82, p < 0.01, partial η2 =0.054) and influencer-product congruence (Wilks’ λ= 0.83, F (2, 205) = 20.77, p < 0.001, partial η2 =0.168). However, the interaction effect was nonsignificant (Wilks’ λ= 0.99, F (2, 205) = 0.68, p = 0.51, partial η2 =0.007). Thus, the PSR between the audience and the influencer could not moderate the effect of influencer-product congruence on the audience’s attitude and purchase intention, H5 was rejected.

As shown in Figure 1, the audience’s attitude towards the product placement was better when the PSR was closer (M = 4.96, SD = 1.23) than the PSR was more distant (M = 4.20, SD = 1.39; F (1, 206) = 11.73, p < 0.01). H1a was supported. The audience’s purchase intention was marginally significantly higher when the PSR was closer (M = 3.43, SD = 1.28) than the PSR was more distant (M = 3.01, SD = 1.27; F (1, 206) = 3.79, p = 0.053), so H1b received partial support.

|

Figure 1 The audience’s attitude towards the product placement and purchase intention in different psr conditions. Abbreviation: PSR, Parasocial Relationship. |

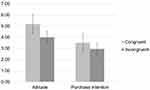

Furthermore, the audience’s attitude towards the product placement with influencer-product congruence (M = 5.17, SD = 1.23; Figure 2) was significantly better than that of the product placement without influencer-product congruence (M = 3.99, SD =1.24; F (1, 206) = 41.29, p < 0.001), supporting H3a. The audience’s purchase intention was higher when the influencer-product was congruent (M = 3.50, SD = 1.34) than when it was incongruent (M = 2.95, SD = 1.20; F (1, 206) = 7.75, p < 0.01). Thus, H3b was supported.

|

Figure 2 The audience’s attitude towards the product placement and purchase intention in different influencer-product congruence conditions. |

The Mediating Role of Psychological Reactance on the Effect of PSR (H2)

The simple mediation model via PROCESS macro for SPSS58 was used to test the mediation hypotheses (H2 and H4). Gender, grade, monthly income, urban/rural residency, daily time spent on Bilibili were controlled.

We first tested the mediation effect of psychological reactance on the relationship between PSR and the audience’s attitude towards the product placement itself. According to Table 1, PSR and control variables explained 8% of the total variances in the audience’s reactance (R2 = 0.08, F (6, 203) = 3.08, p < 0.01). PSR was negatively associated with audiences’ reactance (β = −0.50, p < 0.001). When reactance was considered, along with PSR and control variables, they explained 49% of the total variances in the dependent variable (R2 = 0.49, F (7, 202) = 28.12, p < 0.001). Reactance was negatively related to the audience’s attitude towards the product placement (β = −0.66, p < 0.001). Both the direct effect (direct effect = 0.29, SE = 0.14, 95% CI = 0.01 to 0.57) and the indirect effect of PSR on the audience’s attitude towards the product placement were significant (indirect effect = 0.33, SE = 0.08, 95% CI = 0.16 to 0.50). The above analysis demonstrates that the audience’s reactance mediated the positive effect of PSR on the audience’s attitude towards the product placement, such that the PSR between the audience and the influencer negatively affected the audience’s reactance to the product placement video, and the reduction of reactance made the audience hold a better attitude towards the product placement. Thus, H2a was supported.

|

Table 1 The Mediation Effect of Psychological Reactance on the Effect of PSR on the Audience’s Attitude Towards the Product Placement and Purchase Intention |

When testing the mediation effect of psychological reactance on the relationship between PSR and purchase intention, the negative effect of PSR on reactance was confirmed again (β = −0.50, p < 0.001, Table 1). Again, the level of reactance predicted the audience’s purchase intention (β = −0.26, p < 0.001). However, PSR, reactance and control variables only explained 12% of the total variances in the purchase intention (R2 = 0.12, F (7, 202) = 4.02, p < 0.001). The indirect effect of PSR on purchase intention was significant (indirect effect = 0.13, SE = 0.05, 95% CI = 0.04 to 0.25) but the direct effect was nonsignificant (direct effect = 0.24, SE = 0.18, 95% CI = −0.10 to 0.59). Therefore, the PSR between the audience and the influencer raised the audience’s purchase intention by mitigating their reactance; conversely, while the audience perceived a more distant PSR with the influencer, this enhanced their reactance to the product placement and thus reduced their purchase intention. H2b was supported.

The Mediating Role of Psychological Reactance on the Effect of Influencer-Product Congruence (H4)

Influencer-product congruence was negatively associated to the audience’s reactance to the product placement (β = −0.66, p < 0.001, see Table 2), with 13% of the total variances explained in the level of reactance (R2 = 0.127, F (6, 203) = 4.90, p < 0.001). Next, reactance, influencer-product congruence, and control variables explained 53% of the total variances in the attitude towards the product placement (R2 = 0.53, F (7, 202) = 32.79, p < 0.001). The audience’s reactance to the product placement was negatively related to the audience’s attitude (β = −0.61, p < 0.001). Both the direct effect (direct effect = 0.64, SE = 0.14, 95% CI = 0.37 to 0.92) and the indirect effect of influencer-product congruence on the audience’s attitude (indirect effect = 0.40, SE = 0.08, 95% CI =0.24 to 0.56) were significant. Thus, reactance partially mediated the positive relationship between influencer-product congruence and audience attitude. More specifically, influencer-product congruence reduced the audience’s reactance to the product placement video and therefore improved their attitude. H4a was supported.

|

Table 2 The Mediation Effect of Psychological Reactance on the Effect of Influencer-Product Congruence on the Audience’s Attitude Towards the Product Placement and Purchase Intention |

Moreover, the negative effect of influencer-product congruence on reactance was supported again (β = −0.66, p < 0.001, Table 2). The level of reactance was again negatively related to purchase intention (β = −0.24, p < 0.001). The independent variable, mediator and control variables significantly explained 13% of the total variances in the purchase intention (R2 = 0.129, F (7, 202) = 4.28, p < 0.001). The indirect effect of influencer-product congruence on purchase intention was significant (indirect effect = 0.16, SE = 0.06, 95% CI =0.05 to 0.29), whereas the direct effect was not (direct effect = 0.34, SE = 0.18, CI = −0.02 to 0.70). Hence, the relationship between influencer-product congruence and purchase intention was fully mediated by reactance. Influencer-product congruence negatively influenced the audience’s reactance to the product placement and thereby enhanced their purchase intention. H4b was supported.

The Moderating Role of PSR on the Mediating Effect of Psychological Reactance (H6)

We analyzed whether the PSR between audience and influencer (1 = low, 2 = high), moderated the mediating effect of psychological reactance between influencer-product congruence (1 = low, 2 = high) and the audience’s attitude towards the product placement and purchase intention by using the PROCESS macro model 7.58 Gender, grade, monthly income, urban/rural residency, daily time spent on Bilibili were controlled.

Both moderated mediation models showed that different levels of PSR did not change the effect of influencer-product congruence on audience’s reactance to the product placement, since the interaction term was not significant (B = 0.05, SE = 0.34, t = 0.15, p = 0.88, see Table 3). Thus, H6 was rejected.

|

Table 3 Regressing Two-Way Interaction Between Influencer-Product Congruence and the Level of PSR on Reactance |

Additional Analysis

We replicated the moderated mediation analysis by replacing the categorical variables of PSR and influencer-product congruence with their measured continuous variables. PSR significantly moderated the negative effect of expertise (the operational variable of influencer-product congruence) on reactance (B = 0.09, SE = 0.04, t = 2.02, p < 0.05, see Table 4). The effect of expertise on the audience’s reactance was weaker among those reporting a high level of measured PSR (1 SD above the mean of the measured level of PSR; B = −0.14, SE = 0.07, t = −1.92, p = 0.056) compared to those reporting a low level of measured PSR (1 SD below the mean of the measured level of PSR; B = −0.33, SE = 0.08, t = −4.09, p < 0.001).

|

Table 4 Regressing Two-Way Interaction Between Expertise and the Measured Level of PSR on Reactance |

In addition, the moderated mediation effect of PSR on the relationship between expertise and attitude towards the product placement via reactance was significant (95% CI = −0.10 to −0.002, effect size: −0.05, SE = 0.02). The conditional indirect effect was only significant among those experiencing low levels of PSR (effect = 0.18, SE = 0.04, 95% CI = 0.10 to 0.26). Therefore, for the audience who perceived a close PSR with the influencer, their evaluation of the influencer’s expertise might not affect their reactance to the product placement; for those who perceived a distant PSR with the influencer, their low evaluation of expertise might trigger their reactance to the product placement and thus cause a bad attitude towards the product placement. However, the moderated mediation effect of PSR on the relationship between expertise and purchase intention via psychological reactance was nonsignificant (95% CI = −0.03 to 0.003).

Discussion

Product placements are not always welcomed because they try to persuade audiences to purchase. This could cause a perception of freedom restriction, which we should seek to minimize. This study examined two influencer-related factors which might enhance audience attitude towards the product placement and their purchase intention by lowering their level of reactance: PSR and influencer-product congruence. Overall, our findings suggest that PSR and influencer-product congruence could enhance the audience’s attitude toward product placement and their purchase intentions, and these positive effects occurred through lowered levels of audience’s reactance. Additionally, we found that the level of expertise predicted reactance differently among those reporting a high versus low level of measured PSR. Our results show that reactance can remain functional in a collectivistic country such as China, and explicate the mechanism by which individual and relational characteristics related to social media influencers affect audience attitudes towards product placements and offer practical implications on product promotion via social media.

Major Findings

First, we found that when audiences recognize a close relationship with social media influencers, even if this relationship is imagined and one-sided, they likely show more acceptance of the product placement and more willingness (although only marginally significant) to buy the product. This finding echoes the existing studies that reported a positive relationship between PSR and the audience’s response.9,10,15,16,40 Further, product placements via online videos can have advantages compared to traditional mass media. This is because when the connection between the audience and the source of an advertisement is beyond momentary exposure,59 the relation between them may change from media-audience to a semi-interpersonal, influencer-follower relation, which exhibits more resemblance with “friendship”.59,60 Therefore, audiences may evaluate the product placement as they evaluate the recommendation from a “friend” rather than a sale attempt from a brand. Thus, as an example of relational factors, a close PSR can be leveraged to shape audience attitude and their purchase intention. Thus, an interesting question for future research is what strategies influencers use to nurture PSR with their followers, which can be examined from the perspectives of self-presentation and linguistics.

Furthermore, we extended the aforementioned findings by explicating that these effects occur through attenuating audiences’ reactance. As Lou60 found, when the audience has established a close PSR with the influencer, they may not question that the influencer gains economic benefits by violating ethics when posting an advertisement and therefore diminish the value of the content posted by the influencer. Hence, as mentioned earlier, when individuals perceived a closer PSR with the influencer, they reported a lower level of reactance probably because they interpreted the influencer’s recommendation as genuine suggestions. Besides, Breves, Liebers, et al50 argued that PSR with social media influencers were usually derived from repeated user interactions. These interactions may cause a positive schema of the influencer such as being trustworthy.50 This schema can change audience’s appraisal of the product placements by making them feel less limited.49,50

In addition to PSR, our results show that when influencers recommend products within their own expertise, the audience may demonstrate more preference and a higher level of purchase intention. This finding aligns with previous studies that emphasized the persuasive effect of influencer-product congrence15,16,46,47 and confirms the match-up hypothesis.42 Besides, the present study successfully replicated the manipulation of congruence by Till and Busler43 and extended their argument that emphasized the match between the character’s expertise and the feature of products in the social media context. Furthermore, we found that the positive effect of influencer-product congruence was a result of lowered levels of reactance. Prior research demonstrated that influencer-product congruence boosted advertising effects because congruence led to positive impressions of the influencers.15,46,47 We extended these studies by explaining how this process might happen which centers on psychological reactance. One possible explanation is that the influencer-product congruence may affect people’s attribution of the product exposure. In particular, when an influencer’s expertise fits the product, audiences likely think that the influencer recommends the product out of his/her genuine approval of the product14 or affectionate intention.61 Conversely, when the influencer is promoting a product outside his/her expertise, audiences might attribute the product placement to a calculative motive, that is, recognizing the advertising intent or even assuming an “ulterior motive of marketing communication”61 behind the recommendation.14,62 Consequently, this incongruence might make them feel their freedom of choice was limited.

We also tested whether PSR moderated the relationship between influencer-product congruence and audience’s attitude and purchase intention. We did not find any significant moderation effects. Yet the measured level of PSR moderated the effect of the influencer’s perceived expertise on psychological reactance, which further predicted audience attitude. Likewise, this moderated mediation effect was confirmed such that the audience perceiving a closer relationship with the influencer were less likely to demonstrate reactance because of the mismatch between the influencer and the product and thereby hold a worse attitude towards the product placement. This suggests that individuals might be more lenient to the influencers they liked. Notably, this does not mean that audience disregards the expertise of the influencers they like. In fact, in a recent study some consumers reported that although they trusted their favorite influencers, they would remain rational in their consumption.60 Besides, the marginally significant effect of perceived expertise on reactance among those reporting a closer PSR also suggests that individuals still evaluated the expertise of the influencer, only to a lesser extent.

If PSR did moderate the effect of influencer-product congruence on psychological reactance (or even attitude and purchase intention), one possible reason for the nonsignificant interaction effects between the categorical variables of PSR and influencer-product congruence was that the distance between high and low levels of PSR in the present study was close. In other words, our participants did not demonstrate too much enthusiasm for or aversion against the influencer. Furthermore, although social media influencer’s expertise plays an important role in persuasion, heightened levels of PSR did lower the impact of the expertise. Thus, purchase decision making may be a joint product of central and heuristic processing. On the one hand, individuals can be influenced by their evaluations of the influencer’s expertise, which suggests the role that central processing plays in purchase decision making. On the other hand, individuals can also be influenced by their imagined, one-sided relationship, representing heuristic processing of decision making. More importantly, this heuristic processing based on audience affection can affect the impact of central processing, which suggests the boundary limitation of the role that cognitive evaluations play in purchase decision making.

Theoretical Implications

This research provides important theoretical implications on how social media users may be influenced by product placements in online videos. Specifically, our findings highlight the key role that psychological reactance plays in shaping individuals’ attitudes towards product placements and purchase intention. Hence, this study provides a perspective which centers on psychological reactance for explicating how affective (ie, PSR) and cognitive (ie, influencer-product congruence) evaluations of social media influencers may shape audience attitude and purchase intention.

Moreover, through an experiment conducted in China, we provided evidence showing that even in a collectivist culture, the persuasive attempt still has the potential to evoke one’s reactance and thereby the failure of persuasion. This study supports the finding by Quick and Kim36 but contradicts the other cross-cultural studies19–21 we mentioned earlier. Although we did not compare our findings with research in the individualistic culture, we still call for scholarly attention to the effect of reactance on consumer attitude in the East Asian context.

In addition, the present study sheds light on the source-related factors (ie, PSR and influencer-product congruence) that affect the persuasive effect of the product placement posted by influencers. Product placement is not a type of advertisements that only appear in the era of social media. The two-way interactivity of social media and individualization of the advertisement source calls for future attention to the source features of the product placement rather than content features.

Besides, our results suggest how PSR and influencer-product congruence might interact to predict psychological reactance. Although individuals evaluated the product based on their perception of the expertise of the influencer, this effect could be compromised by affective factors such as their imaginary relationship with the influencer, perhaps because technological factors have reshaped consumers’ relationships with the products and their endorsers. Specifically, consumers might make different attributions of the recommendation by different influencers, depending on their level of PSR. Future research should examine the potential mediation effect of attribution in this process.

Practical Implications

This study provides practical implications for advertisers. First, prior to placing product commercials in online videos, advertisers need select target influencers carefully. Advertisers should have a basic level of knowledge of the influencers’ expertise and select those whose expertise match their product.

In addition, fame does not equal the level of impact of social media influencers on their followers. Advertisers should pay attention to the cues suggesting the extent to which the influencers are close to their followers. Examples of these cues include followers’ comments and the interactions initiated by the influencers.

Finally, given the key role that psychological reactance played in shaping audience attitude and purchase intention, advertisers should be particularly alert to users’ negative responses to product placements and adjust marketing strategies accordingly, even in the context of collectivist cultures that place less emphasis on freedom or autonomy.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study has some limitations which need to be addressed in future research. First, we used a convenience sample of college students, which limits the generalizability of the current findings. Second, although the manipulation of PSR was successful, the mean difference in the level of PSR between the high and low conditions was relatively small, which might account for the nonsignificant interaction effect between PSR and influencer-product congruence.

As mentioned earlier, previous research on the match-up hypothesis suggested that the influencer-product congruence may involve multiple characteristics,42–44,63 yet we only focused on the expertise. It is interesting to examine whether multiple dimensions of influencer characteristics interact to affect perceived influencer-product congruence.

Moreover, this research focuses exclusively on food-related products. Future studies can benefit in terms of generalizability if other types of products can be included.

Finally, as explained earlier, we speculated that PSR and influencer-product congruence may affect psychological reactance by affecting individual attribution of product placements. Future research should test the potential connection between attribution and psychological reactance and examine what factors may affect attribution.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Gerhards C. Product placement on YouTube: an explorative study on YouTube creators’ experiences with advertisers. Converg Int J Res New Media Technol. 2019;25(3):516–533. doi:10.1177/1354856517736977

2. Rasmussen L. Parasocial interaction in the digital age: an examination of relationship building and the effectiveness of youtube celebrities. J Soc Media Soc. 2018;7(1):280–294.

3. Hudders L, De Jans S, De Veirman M. The commercialization of social media stars: a literature review and conceptual framework on the strategic use of social media influencers. Int J Advert. 2021;40(3):327–375. doi:10.1080/02650487.2020.1836925

4. Chan FFY, Lowe B. Placing products in humorous scenes: its impact on brand perceptions. Eur J Mark. 2021;55(3):649–670. doi:10.1108/EJM-10-2018-0701

5. Jin SV, Muqaddam A. Product placement 2.0:“Do brands need influencers, or do influencers need brands? J Brand Manag. 2019;26(5):522–537. doi:10.1057/s41262-019-00151-z

6. Marchand A, Hennig-Thurau T, Best S. When James Bond shows off his Omega: does product placement affect its media host? Eur J Mark. 2015;49(9–10):1666–1685. doi:10.1108/EJM-09-2013-0474

7. Tessitore T, Geuens M. Arming consumers against product placement: a comparison of factual and evaluative educational interventions. J Bus Res. 2019;95:38–48. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.09.016

8. Farivar S, Wang F, Yuan Y. Opinion leadership vs. para-social relationship: key factors in influencer marketing. J Retail Consum Serv. 2021;59:102371. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102371

9. Hwang K, Zhang Q. Influence of parasocial relationship between digital celebrities and their followers on followers’ purchase and electronic word-of-mouth intentions, and persuasion knowledge. Comput Hum Behav. 2018;87:155–173. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2018.05.029

10. Kim H, Ko E, Kim J. SNS users’ para-social relationships with celebrities: social media effects on purchase intentions. J Glob Sch Mark Sci. 2015;25(3):279–294. doi:10.1080/21639159.2015.1043690

11. Moyer-Gusé E. Toward a theory of entertainment persuasion: explaining the persuasive effects of entertainment-education messages. Commun Theory. 2008;18(3):407–425. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.2008.00328.x

12. Moyer-Gusé E, Jain P, Chung AH. Reinforcement or reactance? Examining the effect of an explicit persuasive appeal following an entertainment-education narrative. J Commun. 2012;62(6):1010–1027. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01680.x

13. Moyer-Gusé E, Nabi RL. Explaining the effects of narrative in an entertainment television program: overcoming resistance to persuasion. Hum Commun Res. 2010;36(1):26–52. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.2009.01367.x

14. Mishra AS, Roy S, Bailey AA. Exploring brand personality–celebrity endorser personality congruence in celebrity endorsements in the Indian context. Psychol Mark. 2015;32(12):1158–1174. doi:10.1002/mar.20846

15. Breves P, Liebers N, Abt M, Kunze A. The perceived fit between Instagram influencers and the endorsed brand: how influencer–brand fit affects source credibility and persuasive effectiveness. J Advert Res. 2019;59(4):440–454. doi:10.2501/JAR-2019-030

16. Torres P, Augusto M, Matos M. Antecedents and outcomes of digital influencer endorsement: an exploratory study. Psychol Mark. 2019;36(12):1267–1276. doi:10.1002/mar.21274

17. van Dam S, van Reijmersdal EA. Insights in adolescents’ advertising literacy, perceptions and responses regarding sponsored influencer videos and disclosures. Cyberpsychology J Psychosoc Res Cyberspace. 2019;13(2). doi:10.5817/CP2019-2-2

18. Carlitz A. The Impact of Video Advertisement Placement and Video Advertisement Transparency on Video Advertisement Avoidance: Pre-Rolls, Mid-Rolls, and Psychological Reactance [Dissertation]. Ohio University; 2020.

19. Bang H, Choi D, Yoon S, Baek TH, Kim Y. Message assertiveness and price discount in prosocial advertising: differences between Americans and Koreans. Eur J Mark. 2021;55(6):1780–1802. doi:10.1108/EJM-10-2019-0791

20. Kim Y, Baek TH, Yoon S, Oh S, Choi YK. Assertive environmental advertising and reactance: differences between South Koreans and Americans. J Advert. 2017;46(4):550–564. doi:10.1080/00913367.2017.1361878

21. Xu J. The impact of self-construal and message frame valence on reactance: a cross-cultural study in charity advertising. Int J Advert. 2019;38(3):405–427. doi:10.1080/02650487.2018.1536506

22. Chan FFY, Petrovici D, Lowe B. Antecedents of product placement effectiveness across cultures. Int Mark Rev. 2016;33(1):5–24. doi:10.1108/IMR-07-2014-0249

23. Boerman S, van Reijmersdal E, Neijens P. Sponsorship disclosure: effects of duration on persuasion knowledge and brand responses. J Commun. 2012;62:1047–1064. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01677.x

24. Brehm JW. A Theory of Psychological Reactance. Academic Press; 1966.

25. Brehm SS, Brehm JW. Psychological Reactance: A Theory of Freedom and Control. Academic Press; 1981.

26. Dillard JP, Shen L. On the nature of reactance and its role in persuasive health communication. Commun Monogr. 2005;72(2):144–168. doi:10.1080/03637750500111815

27. Reynolds-Tylus T. Psychological reactance and persuasive health communication: a review of the literature. Front Commun. 2019;4. doi:10.3389/fcomm.2019.00056

28. Edwards SM, Li H, Lee JH. Forced exposure and psychological reactance: antecedents and consequences of the perceived intrusiveness of pop-up ads. J Advert. 2002;31(3):83–95. doi:10.1080/00913367.2002.10673678

29. van Reijmersdal EA, Tutaj K, Boerman SC. The effects of brand placement disclosures on skepticism and brand memory. Commun - Eur J Commun Res. 2013;38(2). doi:10.1515/commun-2013-0008

30. Chang S. Psychological Reactance and Branded Product Placement [Dissertation]. East Lansing: Michigan State University; 2005.

31. Li C, Meeds R. Factors affecting information processing of internet advertisements: a test on exposure condition, psychological reactance, and advertising frequency. In:

32. Balasubramanian SK. Beyond advertising and publicity: hybrid messages and public policy issues. J Advert. 1994;23(4):29–46. doi:10.1080/00913367.1943.10673457

33. Chan FFY. Product placement and its effectiveness: a systematic review and propositions for future research. Mark Rev. 2012;12(1):39–60. doi:10.1362/146934712X13286274424271

34. Guo F, Ye G, Hudders L, Lv W, Li M, Duffy VG. Product placement in mass media: a review and bibliometric analysis. J Advert. 2019;48(2):215–231. doi:10.1080/00913367.2019.1567409

35. Gupta PB, Gould SJ. Consumers’ perceptions of the ethics and acceptability of product placements in movies: product category and individual differences. J Curr Issues Res Advert. 1997;19(1):37–50. doi:10.1080/10641734.1997.10505056

36. Quick BL, Kim DK. Examining reactance and reactance restoration with South Korean adolescents: a test of psychological reactance within a collectivist culture. Commun Res. 2009;36(6):765–782. doi:10.1177/0093650290346797

37. Horton D, Wohl RR. Mass communication and para-social interaction. Psychiatry. 1956;19(3):215–229. doi:10.1080/00332747.1956.11023049

38. Reinikainen H, Munnukka J, Maity D, Luoma-aho V. ‘You really are a great big sister’ – parasocial relationships, credibility, and the moderating role of audience comments in influencer marketing. J Mark Manag. 2020;36(3–4):279–298. doi:10.1080/0267257X.2019.1708781

39. Dibble JL, Hartmann T, Rosaen SF. Parasocial interaction and parasocial relationship: conceptual clarification and a critical assessment of measures. Hum Commun Res. 2016;42(1):21–44. doi:10.1111/hcre.12063

40. Lee JE, Watkins B. YouTube vloggers’ influence on consumer luxury brand perceptions and intentions. J Bus Res. 2016;69(12):5753–5760. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.04.171

41. Tukachinsky R, Sangalang A. The effect of relational and interactive aspects of parasocial experiences on attitudes and message resistance. Commun Rep. 2016;29(3):175–188. doi:10.1080/08934215.2016.1148750

42. Kamins MA. An investigation into the “match-up” hypothesis in celebrity advertising: when beauty may be only skin deep. J Advert. 1990;19(1):4–13. doi:10.1080/00913367.1990.10673175

43. Till BD, Busler M. The match-up hypothesis: physical attractiveness, expertise, and the role of fit on brand attitude, purchase intent and brand beliefs. J Advert. 2000;29(3):1–13. doi:10.1080/00913367.2000.10673613

44. Solomon MR, Ashmore RD, Longo LC. The beauty match-up hypothesis: congruence between types of beauty and product images in advertising. J Advert. 1992;21(4):23–34. doi:10.1080/00913367.1992.10673383

45. Kim S, Wang K, Jhu W, Gao Y. The best match-up of airline advertising endorsement and flight safety message. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag. 2016;28(11):2533–2552. doi:10.1108/IJCHM-03-2015-0130

46. Janssen L, Schouten AP, Croes EA. Influencer advertising on Instagram: product-influencer fit and number of followers affect advertising outcomes and influencer evaluations via credibility and identification. Int J Advert. 2022;41(1):101–127. doi:10.1080/02650487.2021.1994205

47. Schouten AP, Janssen L, Verspaget M. Celebrity vs. influencer endorsements in advertising: the role of identification, credibility, and product-endorser fit. Int J Advert. 2020;39(2):258–281. doi:10.1080/02650487.2019.1634898

48. Kelley HH, Michela JL. Attribution theory and research. Annu Rev Psychol. 1980;31(1):457–501. doi:10.1146/annurev.ps.31.020180.002325

49. Breves P, Amrehn J, Heidenreich A, Liebers N, Schramm H. Blind trust? The importance and interplay of parasocial relationships and advertising disclosures in explaining influencers’ persuasive effects on their followers. Int J Advert. 2021;40(7):1209–1229. doi:10.1080/02650487.2021.1881237

50. Breves P, Liebers N, Motschenbacher B, Reus L. Reducing resistance: the impact of nonfollowers’ and followers’ parasocial relationships with social media influencers on persuasive resistance and advertising effectiveness. Hum Commun Res. 2021;47(4):418–443. doi:10.1093/hcr/hqab006

51. Yuan S, Lou C. How social media influencers foster relationships with followers: the roles of source credibility and fairness in parasocial relationship and product interest. J Interact Advert. 2020;20(2):133–147. doi:10.1080/15252019.2020.1769514

52. Boerman S, van Reijmersdal EA. Disclosing influencer marketing on youtube to children: the moderating role of para-social relationship. Front Psychol. 2020;10. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.03042

53. Quick BL. What is the best measure of psychological reactance? An empirical test of two measures. Health Commun. 2012;27(1):1–9. doi:10.1080/10410236.2011.567446

54. Bleier A, Eisenbeiss M. The importance of trust for personalized online advertising. J Retail. 2015;91(3):390–409. doi:10.1016/j.jretai.2015.04.001

55. Luna-Nevarez C, Torres IM. Consumer attitudes toward social network advertising. J Curr Issues Res Advert. 2015;36(1):1–19. doi:10.1080/10641734.2014.912595

56. Rubin AM, Perse EM. Audience activity and soap opera involvement a uses and effects investigation. Hum Commun Res. 1987;14(2):246–268. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.1987.tb00129.x

57. Ohanian R. Construction and validation of a scale to measure celebrity endorsers’ perceived expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness. J Advert. 1990;19(3):39–52. doi:10.1080/00913367.1990.10673191

58. Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. Guilford publications; 2017.

59. Bond BJ. Following your “friend”: social media and the strength of adolescents’ parasocial relationships with media personae. Cyberpsychology Behav Soc Netw. 2016;19(11):656–660. doi:10.1089/cyber.2016.0355

60. Lou C. Social media influencers and followers: theorization of a trans-parasocial relation and explication of its implications for influencer advertising. J Advert. 2022;51(1):4–21. doi:10.1080/00913367.2021.1880345

61. Kim DY, Kim HY. Influencer advertising on social media: the multiple inference model on influencer-product congruence and sponsorship disclosure. J Bus Res. 2021;130:405–415. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.02.020

62. De Cicco R, Iacobucci S, Pagliaro S. The effect of influencer–product fit on advertising recognition and the role of an enhanced disclosure in increasing sponsorship transparency. Int J Advert. 2021;40(5):733–759. doi:10.1080/02650487.2020.1801198

63. Kamins MA, Gupta K. Congruence between spokesperson and product type: a matchup hypothesis perspective. Psychol Mark. 1994;11(6):569–586. doi:10.1002/mar.4220110605

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.