Back to Journals » Advances in Medical Education and Practice » Volume 9

Who are the right teachers for medical clinical students? Investigating stakeholders’ opinions using modified Delphi approach

Authors Shaterjalali M , Yamani N, Changiz T

Received 12 June 2018

Accepted for publication 8 September 2018

Published 8 November 2018 Volume 2018:9 Pages 801—809

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S176480

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Md Anwarul Azim Majumder

Maria Shaterjalali, Nikoo Yamani, Tahereh Changiz

Department of Medical Education, Medical Education Research Center, Isfahan University of Medical Science, Isfahan, Iran

Purpose: The purpose of this study was to realize that learning in a clinical setting, the interactions of the students with teachers, learning materials, and learning environments are essential. In clinical education, different groups may play the role of the teacher for medical students. This study was designed to determine the optimal characteristics for medical clinical teachers, their selection criteria, and their responsibilities.

Methods: The modified Delphi technique was used in this study. Participants comprised vice-chancellors of education, deans of medical schools, and deputies of education in medical schools across Iran. This study was conducted in three rounds. In the first round, the participants were selected using purposive sampling, and the data were collected through focus group discussions and analyzed through content analysis. The data collection tool in the second and third rounds involved a questionnaire derived from the first round, and the consensus criterion to accept or reject the questionnaire items was frequency distribution.

Results: The final number of statements in the first round was 157. The second-round questionnaire was designed in the four sections of teaching team, selection criteria, task description of the teaching team (including faculties, specialist staffs, residents, general practitioners, and health and treatment staff), and incentives separately for the specialist staff, residents, general practitioners, and health and treatment staff. The third-round questionnaire included feedback and items that were not agreed upon in the second round.

Conclusion: The results of this study indicated the necessity of forming a teaching team, paying attention to the selection criteria, and planning requirements for assigning responsibilities to the teaching team in accordance with the objectives, programs, and requirements of medical schools, along with using strategies to attract participation and create motivation in the teaching team.

Keywords: clinical education, clinical teachers, clinical staff, residents, general practitioners

Introduction

As a major component of the medical curriculum, clinical education entails many objectives. While the students mature their medical knowledge and clinical practice during the clinical course, they also develop communication skills. Moreover, along with the progress in clinical thinking and the ability to interact with other professions, they acquire their role as a physician.1

Teachers, the learning material, and the learning environment are essential to the realization of the learning process in the clinical setting. Evidence suggests that the interactions between students and these components determine students’ learning. As a result, learning during clinical education is partly related to the teachers’ characteristics. What characteristics does an excellent clinical teacher have? Irby et al (1978, 1991) suggested the six factors of knowledge, organization, teaching enthusiasm, supervision skills, clinical competence, and professionalism as contributory parameters to excellent clinical education.2–4 Harden also mentioned 12 roles for teachers in the six domains of “information provider, role model, facilitator, examiner, planner, and resource developer’’.5 According to Harden, the quality with which a clinical teacher performs is the most important factor in students’ learning in clinical education.5 The perspectives of assistants and faculties were enquired by Stenfors-Hayes et al6 concerning characteristics of ideal clinical teachers. They reported similar criteria in two studies including passion, commitment, supportiveness, role model, offering the content in an organized and clear manner, active researcher, clinically empowered, and teaching enthusiasm.6

Education in clinical setting, however, faces many challenges, and despite the specialists’ preparedness for teaching, the existing challenges may lead to ignoring educational tasks7 or make difficulties in coordinating multiple tasks with them.8 Clinical teachers have challenges such as time constraint, clinical research and executive roles along with their educational role, unpredictable clinical settings, and the related problems, simultaneous presence of learners of different levels, lack of motivation and rewards for teaching, inappropriate clinical setting, and challenges related to patients.9,10

It is obvious that the presence of creative and eminent clinical teachers, who both supervise the development of clinical skills in students and simultaneously manifest significant professional features, is necessary to make changes in students.11 Presupposing that learning of students is not merely subsequent to faculties but a bigger community, and quoting Hoffman and Donaldson, Pratt et al12 stated that students’ learning depends on many factors, including the number of health care team members and students’ conflicting roles in rotations. With regard to role of other health team members along with faculties, such as nurses, health and treatment staffs, assistants, and so on, in helping students’ learning, the participating students in Pratt et al’s study believed that these underlying factors were contributory.12

The increasing focus on the role of residents as teachers indicates the existence of a problem with the teacher-centered approach. In the clinical setting, residents play their roles as teachers very effectively,13 and medical students often refer to them as their teachers. In addition, while transferring knowledge and skills, residents also play an important role in teaching values and professionalism.13–17 Carney et al reflected the better performance quality of students trained by preceptors in community clinics affiliated with academic centers.18 Quoting from Silverstone’s qualitative research concerning the cooperation of general practitioners (GPs) in education, van der Zwet et al19 state that the GP instructors play important roles in effective teaching in community. Students mention features such as good teacher, role model, and provider of a positive learning atmosphere for a good GP.19 van der Hem-Stokroos et al also state that nurses’ participation in teaching clinical skills to medical students can be valuable and should be taken into account.20

The challenges faced by clinical teachers and the obligation of medical schools to be accountable for the knowledge, attitudes, skills, and abilities of their graduates led us to conduct a study to identify the features of excellent clinical teachers (all effective tutors in learning) in the clerkship and internship, to prepare a list of and describe optimal characteristics of these teachers, to give suggestions for the improvement of the existing conditions in Iran, and to draft a proposal for the improvement of the standards of clinical education plan in the general medicine program. Modified Delphi is suggested in cases where the purpose is to discover perspectives, to identify all decision-making ideas,21 to write a draft, or to make a decision.22 We have chosen the modified Delphi technique in order to explore the ideas of experts and their professional judgments throughout Iran. Our aim in this study was to extract the opinions of experts and planners in this field, to prepare a list of local optimum conditions considering the diversity of resources and facilities of medical schools in Iran, and to reach an agreement on these opinions and suggestions.

Methods

Participants and study design

We used the modified Delphi technique in this study. Consensus group methods are systematic approach and are based on the idea that a more accurate and reliable evaluation will be obtained employing the experts panel. This method is employed to make decisions in a group, to use experts’ knowledge on an extensive area, and to give more credibility to group agreements.23 Participants of this study comprised vice-chancellors of education, deans of medical schools, and deputies of education in medical schools throughout the country. All of them were clinical teachers in medical schools. They have multiple executive, educational, treatment, and research responsibilities. General medicine planners with the above-mentioned positions were eligible to enter the study. This study was conducted in three rounds from June 2016 to August 2017.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research is part of the research project approved under No. 395055 with the ethics code IR.MUI.REC.1395.3.55 in the Vice-chancellery for Research of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. Since the study did not include personal data or clinical trials, approval was deemed not to be necessary. Verbal (audio-recorded) and/or written consent to participate was obtained from all participants in the first round. This consent form was approved by the medical education research center, Isfahan University of Medical Science. In the second and third rounds, participants were informed about the study at the time of data collection and were made aware that participation in the study, which involved completing survey, was completely voluntary.

Delphi’s first round

The first round was conducted using directed content analysis method,21,24,25 to provide a list of optimal conditions for undergraduate clinical medical teachers. Participants in this round included 20 vice-chancellors of education in medical sciences universities and deputies of education in medical schools who were selected using purposive sampling with maximum variation. The questions posed in this round were designed using experts’ opinions that were subsequently applied in a pilot study on a group comprising some deputies of education in medical schools. The questions were revised and asked in the form of general questions followed by probing questions. In Iran, clinical teachers, mostly faculties, are responsible for education in clinical setting, consisting of hospital ward, hospital ambulatory, community ambulatory, and skill lab for clerkship and internship. In probing question, we separately asked questions about all these settings.

Data collection methods included online focus group discussions (webinars) and telephone or face-to-face individual semi-structured interviews. Overall, data collection was performed through two online focus group discussions, four face-to-face interviews, and eight telephone interviews. After extracting the semantic units, the generated statements in this step were classified (Table 1). When the resulting statements were categorized, the classes were set up in such a way that in addition to answering the basic questions, they could be used for designing the questionnaire to be employed in the next round. Moreover, the four criteria proposed by Lincoln and Guba26 were employed to determine the rigor and trustworthiness of the data.27

| Table 1 Main category, subcategory, and subclasses of optimal clinical teachers Note: Motivation and financial and non-financial incentives. |

Delphi’s first-round questions were:

- Who is (are) the best teacher(s) for clerkship and internship?

- What is your opinion about the teaching of students by a structured team of faculties, specialist staffs, residents, GPs, nurses, and other health care system staffs?

- In case of need for a teaching team, how should it be tailored and prepared?

- Should non-faculty teachers (eg, residents, specialist staffs, GPs) be given an official letter for teaching and receive payments for their work?

Delphi’s second round

Building on the results from the first round, a questionnaire with 41 statements was designed in four sections. A proper scale was considered for each section. Sampling for this round was done via census. First, the electronic questionnaire was sent to the email address of the vice-chancellors of education in medical sciences universities, the deans, and the deputies of education of medical schools throughout Iran. Two weeks after the first email, a reminder was sent to them. Because of the low number of replies, paper questionnaires were distributed among the participants after a month, and they were asked to complete the questionnaires if they had not responded to the electronic mails. The level of agreement was to obtain a 70% frequency. In cases where there was a 70% agreement in the responses, that item was accepted; and in cases of 70% disagreement on an item, it was discarded. Options that did not meet these criteria were again raised in the third round.23

Delphi’s third round

The third-round questionnaire consisted of feedback on the second-round responses and other questions. The questionnaire comprised 22 questions in the three domains of selection criteria, task description of the teaching team, and incentives. All the second-round participants received the questionnaire for this round. The agreement criterion was the same as that of the second round.

Validity and reliability of the tool

To determine the face and content validity of the second and third rounds of Delphi, the questionnaires of both the rounds were assessed and reviewed by experts in several stages. To confirm the reliability of the questionnaires, the alpha coefficient with an emphasis on internal consistency was used.

Results

The number of participants in the first round was 20, 54 returned the questionnaire in the second round, and 20 completed the questionnaire in the third round. There were 223 statements in the first round, which reduced to 157 after eliminating or merging similar statements. In the first round, there were 25 statements in response to the first question, 42 in response to the second question, 59 in response to the third question, and 31 in response to the fourth question (Table 1).

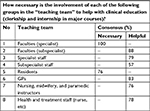

The second round was designed in the following four sections: 1) teaching team with eight items; 2) selection criteria with 12 items; 3) task description and empowerment of the teaching team including faculties, specialist staffs, residents, GPs, nursing, midwifery and paramedical instructors, and health and treatment staffs with 16 items; and 4) incentives separately devised for specialist staffs, residents, GPs, nursing; midwifery and paramedical instructors; and health care and treatment staffs with five items. The final results (rounds) are presented in Tables 2–5.

| Table 2 Teaching team Abbreviation: GPs, general practitioners. |

| Table 3 Selection criteria Abbreviation: GPs, general practitioners. |

| Table 4 Task description of the teaching team Abbreviations: GP, general practitioner; NG, nasogastric. |

| Table 5 Incentives Abbreviation: GP, general practitioner. |

Discussion

While there are studies exploring the viewpoint of teachers and students on clinical education provided by faculties and residents, as well as some studies that implicitly address the role of other members of the health care team in education, no studies were found to have addressed the role of teachers as a team with a structured performance and specific task descriptions. We inquired the extent to which the participating experts agreed upon the formation of a teaching team, selection criteria of team members, the formulation of a framework for responsibilities and tasks, and the way to attract the participation of team members.

Teaching team

The first finding of the study is concerned with the formation of the teaching team. The key feature to form a teaching team is the synergy created in team activities. The combination of capabilities, skills, and energy of the team members is used maximally in teamwork. The purpose of the teaching team in this study was coordinated, structured, and programed engagement of team members in education to enhance the efficacy of the education process. The results showed that, from the viewpoints of the participants in this study, the presence of faculties and assistants in the undergraduate clinical teaching team is essential. On the other hand, they found it helpful to have the subspecialist faculties, specialist and subspecialist staffs, GPs, nursing, midwifery and paramedical instructors, and health and treatment staffs in the teaching team.

Subspecialist faculties are extensively engaged in undergraduate clinical education in most of the Iran-based medical schools. Given that and considering the agreement of the participants on their helpful but not necessary presence, it seems that the roles and tasks assigned to this group of faculties need to be revised. Moreover, general medicine planners should pay attention to the participation of all groups proposed for membership in the teaching team and determine their roles and positions in the teaching team in accordance with the requirements of any university. The national standards of medical doctor program in Iran (edited in 2017) underlines the use of faculties and other instructors in line with the mission of schools and regional features and highlights the establishment of constructive interactions and collaboration with other health sectors for GP training in order to meet the needs of the community.28 The results of this study can be used to realize that aim. In similar lines, findings of Pratt et al’s study indicate that the presence of underlying factors such as residents, nurses, and staffs could be helpful in education from the viewpoint of students.12 Studies have also shown that medical students believe that residents are involved in their education,17,29 and their interactions with assistants in the teaching–learning process have been more important than their communications with the specialist staff and faculties. They considered residents as a complement to the faculties’ teaching methods,30 which is consistent with the view of our participants about the presence of residents in the teaching team. In a qualitative study on the role of residents in clinical education, Busari et al stated, however, that despite the general assumption that teaching is an important role for residents, they do not believe this themselves, and although they will like to have an educational role determined by the educational department for themselves, they do not want it to be included in their evaluation.16 Another study on the educational role of faculties and staffs (specialists and GPs) showed that according to the students, there was no significant difference between these two groups in terms of level of knowledge, teaching of physical examination, interpretations, and patient management.31 This can confirm the helpful presence of specialists and GPs in the teaching team.

Selection criteria

The selection criteria for the members of the teaching team was another parameter that was considered and agreed on in this study. Our participants agreed on the selection of subspecialist and specialist staffs, GPs, nursing, midwifery and paramedical instructors, and health and treatment staff in the teaching team. Nevertheless, everyone agreed on the collaboration of all residents in the teaching team. Approving the scientific and educational competence of specialist staffs and GPs by the relevant department requires the formation of an expert panel at medical schools in order to establish clear criteria for the selection and assessment of their competencies. Also, simultaneous provision of education and treatment by specialist staffs is another point that requires a proper interaction between education and treatment vice-chancelleries of medical sciences universities. The qualification of the nursing, midwifery, and paramedical instructors by their respective schools as well as their introduction to join the teaching team also requires the elaboration of clear task descriptions and confirmation of their capabilities. Participants did not agree on the selection criteria for the health and treatment staffs (66.7%).

The obtained frequency distribution in relation to the specified cutoff limit requires further study. Despite studies on the selection of residents or other groups mentioned above, we did not find any studies on the selection criteria for the teaching team. The participants in this study also agreed on the necessity of formulating clear task descriptions for the teaching team and their empowerment for education and assessment. Medical clinical teachers have a bilateral role in providing services to patients and education. Although all physicians are prepared for the clinical role, few are prepared for the educational role. Lack of adequate knowledge regarding education and teaching and learning strategies leads to insufficient preparation for this professional role.9 Other studies also show that 20%–25% of the work time of residents is spent on education. They must prepare for the role of teaching while preparing for clinical work. Accreditation agencies such as ACGME, in addition to considering the important role of teaching for residents, also support the educational empowerment of them.14,15

Task description of the teaching team

The next finding that was assessed to reach an agreement was the task description of the teaching team members. The results of the study showed that our participants agreed on the implementation of the mentioned task by the faculties. From their point of view, faculties seemed to have a key role in medical education and should be at the head of the teaching team. The study of Ayatollahi et al regarding the viewpoints of interns about the quality of services offered by faculties (on a 5-point Likert scale) showed that faculties obtained a mean of 2.93±1.13 in terms of student preparation for the future job by providing theoretical and practical educations.32 The results of our research showed agreement on participation of residents in describing the rules to students, practical teaching, teaching the procedures, participation in teaching of medical records, collaborating in teaching evidence base medicine, participation in student assessment, and monitoring students’ communications. The results of a self-assessed study on residents in relation to teaching characteristics also showed that they rated their teaching qualities from slightly good to good and evaluated their attitude and technical skills as good.29 In addition to supervising students, they can teach basic clinical skills and patient management to students.30 However, the lack of a clear definition of the role of residents in education, the absence of a detailed task description, or the oversight of their assigned roles can be the reasons for the lack of a positive attitude toward the teaching role of residents in a number of studies.33

The participants in our study agreed on the participation of general physicians of the teaching team in familiarizing interns with common diseases, patient management in health centers, and ultimately the role of a GP in the real workplace. Community health care centers are the real workplace for most GP graduates, and the use of empowered and trained teachers in these settings will be helpful in promoting education. Quoting from the Silverstone’s qualitative research, van der Zwet et al consider GP teachers as an important determinant of the effectiveness of education in community health care centers.19 The study of Vazirinejad et al on the effectiveness of the participation of GP instructors in the internship MD program in health care centers also indicated an increase in the mean score of student assessment and their satisfaction in health care centers with trained GPs.34 The low number of faculties in some medical schools in Iran has necessitated the use of specialist and subspecialist staffs in undergraduate medical education. The lack of definite selection criteria or the lack of their permanent presence has left medical schools with problems in planning to properly benefit from them. The results of this study showed that our participants did not agree on the tasks assigned to specialist and subspecialist staffs, which could be due to the absence of specific rules for employing them. There was little agreement on the task assigned to nursing, midwifery, and paramedical instructors, and health and treatment staffs. It seems that recruiting them should be tailored to curriculum objectives and needs of medical schools. The selection criteria and task descriptions of the teaching team are two areas in our findings that can be used as an implementation procedure to fulfill a number of the national standards of the MD program (edited in 2017).28 These standards are concerned with the assurance of medical schools about the educational qualifications of faculties or instructors, sufficient knowledge of faculties or instructors about the curriculum, devotion of enough time and energy to MD education, and faculty and instructor empowerment.28

Incentives

In order to motivate participation in the teaching team, we investigated the ways to use incentives. The results indicated consensus on issuing official notifications for specialist staffs and GPs participating in the teaching team. There was also agreement on awarding certificates to all members of the teaching team. Participants agreed on giving financial incentives to the teaching team, including specialist staffs; GPs; nursing, midwifery, and paramedical instructors; and health and treatment staff, with the exception of residents. There was also agreement on giving non-financial incentives to the teaching team. Regarding the reduction in the therapeutic activity of the teaching team, no agreement was reached on reducing the activities of residents and GPs. With regard to what the residents think about the added educational program to the residency program, Busari et al declared that they would prefer to teach students if medical responsibilities are decreased.29 Also, in the early clinical exposure, GPs working in community settings and specialists working in hospital clinics were recruited for clinical education. Participants in this educational program reduced their routine work during the teaching time and empowerment sessions were held for them by the university.35 Planners can use the results of this part of our study to fulfill national standards concerning the presence of a medical school that can motivate faculties and instructors.28

One of the limitations of this study was the incorporation of only the experts to learn about the conditions of the clinical teachers and the lack of access to the opinions of the students and staff. The breadth and diversity of the research community in comparison with the participating sample was another limitation of this study. In order to reduce the impact of this limitation on the results, the studied schools were selected from all medical schools throughout the country. Nevertheless reduced response rate in the third round was another problem with this research, which may be due to repetition of rounds and the extent of the research community. Shortage of time of the research participants was another limitation in the collection of data as the participants were infused with multiple executive, educational, and treatment responsibilities.

Assigning some of responsibilities to team members can lead to a reduction in faculty workload and, as a result, to devote more time to teaching to students. Also, using other members of teaching team with definitive tasks will prevent the overlapping of teaching team tasks and education is fully accomplished. It is recommended to medical school deans to consider forming a teaching team while planning for a general medical course. Also evaluation study on the performance of team members in inpatient and outpatient settings and how to participate together is recommended. The studies about effective incentives for continued collaboration in the teaching team and student review are recommended.

Conclusion

Teachers and their quality of performance are among the most influential components in promoting clinical education. The results of this study showed the opinions of our participants on the formation of a teaching team consisting of specialist faculties and residents as essential members on the one hand and subspecialist faculties, specialist staffs, GPs, nursing, midwifery and paramedical instructors, and health and treatment staff as helpful members on the other hand. Other findings of our research were selecting the teaching team according to the agreed specific criteria and determining their responsibilities in the teaching team tailored to the objectives, plans, and requirements of the medical schools. Also, we showed strategies to attract collaboration and motivation for teaching team members. All of these need specific planning. It falls within the authority of policy makers and planners of the schools to plan for implementation of each part of the results.

Data sharing statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available, but can be obtained from the authors on reasonable request. All questionnaires and other materials are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The researchers are grateful to the vice-chancellors of education in medical universities, the MD program deputies of education, and the clinical education deputies, who helped us in this study despite their hectic work schedules. The study was supported by medical education research center, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

Author contributions

MS, TC, and NY developed the design of this study. MS performed statistical analyses. All authors contributed to the analyses and writing of the paper. All authors read and approved the final version. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper, gave approval for the final version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Scheffer C, Edelhäuser F, Tauschel D, Riechmann M, Tekian A. Can final year medical students significantly contribute to patient care? A pilot study about the perception of patients and clinical staff. Med Teach. 2010;32(7):552–557. | ||

Alweshahi Y, Harley D, Cook DA. Students’ perception of the characteristics of effective bedside teachers. Med Teach. 2007;29(2-3):204–209. | ||

Irby DM. Clinical teacher idealness in medicine. J Med Educ. 1978;53: 808–815. | ||

Irby DM, Ramsey P, Gillmore J, Schaad D. Characteristics of ideal clinical teachers of ambulatory care medicine. Acad Med. 1991;66:54–55. | ||

Harden RM, Crosby J. AMEE Guide No 20: The good teacher is more than a lecturer - the twelve roles of the teacher. Med Teach. 2000; 22(4):334–337. | ||

Stenfors-Hayes T, Hult H, Dahlgren LO. What does it mean to be a good teacher and clinical supervisor in medical education? Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2011;16(2):197–210. | ||

Régo P, Peterson R, Callaway L, Ward M, O’Brien C, Donald K. Using a structured clinical coaching program to improve clinical skills training and assessment, as well as teachers’ and students’ satisfaction. Med Teach. 2009;31(12):e586–e595. | ||

Kumar K, Greenhill J. Factors shaping how clinical educators use their educational knowledge and skills in the clinical workplace: a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):68. | ||

Ramani S, Leinster S. AMEE Guide no. 34: Teaching in the clinical environment. Med Teach. 2008;30(4):347–364. | ||

Gandomkar R, Salsali M, Mirzazadeh A. Factors Influencing Medical Education in Clinical Environment: Experiences of Clinical Faculty Members. IJME. 2011;11(3):279–290. | ||

Sutkin G, Wagner E, Harris I, Schiffer R. What makes a good clinical teacher in medicine? A review of the literature. Acad Med. 2008;83(5):452–466. | ||

Pratt DD, Harris P, Collins JB. The power of one: looking beyond the teacher in clinical instruction. Med Teach. 2009;31(2):133–137. | ||

Doumouras A, Rush R, Campbell A, Taylor D. Peer-assisted bedside teaching rounds. Clin Teach. 2015;12(3):197–202. | ||

Mann KV, Sutton E, Frank B. Twelve tips for preparing residents as teachers. Med Teach. 2007;29(4):301–306. | ||

Pasquale SJ, Cukor J. Collaboration of junior students and residents in a teacher course for senior medical students. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):572–576. | ||

Busari JO, Prince KJ, Scherpbier AJ, van der Vleuten CP, Essed GG. How residents perceive their teaching role in the clinical setting: a qualitative study. Med Teach. 2002;24(1):57–61. | ||

Garakyaraghi M, Sabouri M, Avizhgan M, Ebrahimi A, Zolfaghari M. Interns’ Viewpoints toward the Student of Training by Residents in Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. IJME. 2008;7(2):361–369. | ||

Carney PA, Ogrinc G, Harwood BG, Schiffman JS, Cochran N. The influence of teaching setting on medical students’ clinical skills development: is the academic medical center the “gold standard”? Acad Med. 2005;80(12):1153–1158. | ||

van der Zwet J, Hanssen VG, Zwietering PJ, et al. Workplace learning in general practice: supervision, patient mix and independence emerge from the black box once again. Med Teach. 2010;32(7): e294–e299. | ||

van der Hem-Stokroos HH, Scherpbier AJ, van der Vleuten CP, de Vries H, Haarman HJ. How effective is a clerkship as a learning environment? Med Teach. 2001;23(6):599–604. | ||

Keeney S, Hasson F, McKenna H. The Delphi Technique in Nursing and Health Research. Wiley-Blackwell, West Sussex; 2011. | ||

Waggoner J, Carline JD, Durning SJ. Is there a consensus on consensus methodology? Descriptions and recommendations for future consensus research. Acad Med. 2016;91(5):663–668. | ||

Humphrey-Murto S, Varpio L, Gonsalves C, Wood TJ. Using consensus group methods such as Delphi and Nominal Group in medical education research. Med Teach. 2017;39(1):14–19. | ||

Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–115. | ||

Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. | ||

Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Sage Publications, New Dehli. 1985. 416pp. | ||

Wildemuth B.M, Zhang Y. Qualitative Analysis of Content. Available from: http://old-classes.design4complexity.com/7702-F12/qualitativeresearch/content-analysis.pdf. Accessed December 20, 2015. | ||

Ministry of Health and Medical Education [homepage on the Internet]. National Standards of General Medical education doctors of Islamic Republic of Iran. Available from: http://scume.behdasht.gov.ir/. Accessed 20 Nov, 2017. | ||

Busari O, Scherpbier Albert JJA, van der Vleuten Cees PM, Essed Gerard EJ. Residents’ perception of their role in teaching undergraduate students in the clinical setting. Med Teach. 2000;22(4):348–353. | ||

Weinholtz D, Edwards JC. Teaching during Rounds: A Handbook for Attending Physicians and Residents. 1st ed. Tehran: Hayan; 2003. | ||

Woodley N, Mckelvie K, Kellett C. Bedside teaching: specialists versus non-specialists. Clin Teach. 2016;13(2):138–141. | ||

Ayatollahi J, Sharifi MR, Marjani N, Ayatollahi F. Assessing quality of education services at Yazd University of Medical Sciences in 2010. Jmed. 2012;7(2):21–30. | ||

Vahidshahi K, Mahmoudi M, Shahbaznejad L, Zamani H, Ehteshami S. The Attitude of Residents, Interns and Clerkship Students towards Teaching Role of Residents. IJME. 2009;9(2):147–155. | ||

Vazirinejad R, Soltani M, Tagavi M, Rezaeian M. The Efficacy of Participation of Trained General Practitioners on Promoting the Quality of Educational Curriculum of Health Internship Students Working at Health Centers- Rafsanjan 2009. JRUMS. 2011;10(1):19–30. | ||

von Below B, Rödjer S, Wahlqvist M, Billhult A. “I couldn’t do this with opposition from my colleagues”: a qualitative study of physicians’ experiences as clinical tutors. BMC Med Educ. 2011;11(1):79. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.