Back to Journals » Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment » Volume 19

Prescribing Trends for the Same Patients with Schizophrenia Over 20 Years

Authors Yasui-Furukori N , Kawamata Y , Sasaki T, Yokoyama S, Okayasu H , Shinozaki M, Takeuchi Y, Sato A, Ishikawa T, Komahashi-Sasaki H, Miyazaki K , Fukasawa T, Furukori H, Sugawara N , Shimoda K

Received 19 September 2022

Accepted for publication 7 April 2023

Published 17 April 2023 Volume 2023:19 Pages 921—928

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S390482

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Taro Kishi

Norio Yasui-Furukori,1,2 Yasushi Kawamata,1,3 Taro Sasaki,1,4 Saaya Yokoyama,1,5 Hiroaki Okayasu,1,6 Masataka Shinozaki,1,7 Yoshitaka Takeuchi,1,8 Aoi Sato,1,9 Takaaki Ishikawa,1,10 Hazuki Komahashi-Sasaki,1,11 Kensuke Miyazaki,12 Takashi Fukasawa,13 Hanako Furukori,14 Norio Sugawara,1,2 Kazutaka Shimoda1

1Department of Psychiatry, Dokkyo Medical University, School of Medicine, Tochigi, Japan; 2Department of Psychiatry, TMC Shimotsuga, Tochigi, Japan; 3Department of Psychiatry, Kikuchi Hospital, Tochigi, Japan; 4Department of Psychiatry, Asahi Hospital, Tochigi, Japan; 5Department of Psychiatry, Aoki Hospital, Tochigi, Japan; 6Department of Psychiatry, Fudogaoka Hospital, Saitama, Japan; 7Department of Psychiatry, Takizawa Hospital, Tochigi, Japan; 8Department of Psychiatry, Okamotodai Hospital, Tochigi, Japan; 9Department of Psychiatry, Muroi Hospital, Tochigi, Japan; 10Department of Psychiatry, Saitama-Konan Hospital, Saitama, Japan; 11Department of Psychiatry, Kanuma Hospital, Tochigi, Japan; 12Department of Neuropsychiatry, Hirosaki-Aiseikai Hospital, Aomori, Japan; 13Department of Psychiatry, Seinan Hospital, Aomori, Japan; 14Department of Neuropsychiatry, Kuroichi-Akebono Hospital, Aomori, Japan

Correspondence: Norio Yasui-Furukori, Department of Psychiatry, Dokkyo Medical University, School of Medicine, Mibu, Shimotsuga, Tochigi, 321-0293, Japan, Tel +81-282-86-1111, Fax +81-282-86-5187, Email [email protected]

Background: Recent pharmacoepidemiology data show an increase in the proportion of patients receiving second-generation antipsychotic (SGA) monotherapy, but no studies have analyzed the same patients over a long period of time. Therefore, in this study, we retrospectively evaluated schizophrenia patients with available data for 20 years to determine whether the drug treatments in the same patients have changed in the past 20 years.

Methods: The study began in April 2021 and was conducted in 15 psychiatric hospitals in Japan. Schizophrenia patients treated in the same hospital for 20 years were retrospectively examined for all prescriptions in 2016, 2011, 2006, and 2001 (ie, every 5 years).

Results: The mean age of the 716 patients surveyed in 2021 was 61.7 years, with 49.0% being female. The rate of antipsychotic monotherapy use showed a slight increasing trend over the past 20 years; the rate of SGA use showed a marked increasing trend from 28.9% to 70.3% over the past 20 years, while the rate of SGA monotherapy use showed a gradual increasing trend over the past 20 years. The rates of concomitant use of anticholinergics, antidepressants, anxiolytics/sleep medications, and mood stabilizers showed decreasing, flat, flat, and flat trends over the past 20 years, respectively.

Conclusion: The results of this study showed a slow but steady substitution of SGAs for first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) over time, even in the same patients.

Keywords: pharmacoepidemiology, prescription, antipsychotics, trends, schizophrenia

Introduction

Many guidelines state that pharmacotherapy is important in the treatment of schizophrenia, and from various perspectives in these guidelines, monotherapy with an SGA is considered ideal.1–5 Previous studies have shown that SGAs are more commonly used than FGAs; an international study examined international trends in antipsychotic use in 16 countries in 2005 and found an increase in SGA use in all study populations in 2014, but the pattern of antipsychotic use varied widely across countries.6 From the database of prescription data of the international drug safety program, the prescription data of inpatients with schizophrenia from 2000 to 2015 showed that the use of SGAs significantly increased from 62.8% to 88.9%, and the prescription rate of FGAs decreased from 46.6% to 24.7%.7 Such previous studies looking at trends in prescribing have been limited to comparisons of cross-sectional data from period to period. Some of these data may or may not include the same patients. However, there are currently no studies that follow prescribing trends over a long period of time for the same patients.

In actual clinical practice, few drug-naïve patients start treatment with FGAs.6 However, once FGA treatment is switched to SGA treatment in chronically ill patients who had been treated for a long time with FGA, the mental state of the patient often becomes unstable, and for many such patients, FGAs are continued.

Therefore, we hypothesized that patients whose symptoms stabilized on FGAs would be less likely to switch to SGAs and that the proportion of patients using SGAs would be lower than those since many patients who easily switch from FGA to SGA and worsen their psychiatric symptoms have been reported.8,9 Therefore, in this study, we examined whether the medication regimens of schizophrenia patients with available data for the past 20 years changed over this time period.

Methods

In this pharmacoepidemiological study, we investigated real-life prescribing trends related to psychotropic drugs in schizophrenia patients at Dokkyo Medical University Hospital and its affiliated hospitals. The study was initiated in April 2021 and was conducted in 15 psychiatric hospitals. Three hospitals are in Aomori Prefecture, two in Saitama Prefecture, and the rest in Tochigi Prefecture. Because they are geographically separated by 700 km, patients are not sampled from the same region. In addition, there is variation in the patient population because two of the hospitals are general hospitals with a psychiatry department, and the others are single-department psychiatric hospitals. In addition, clinics were not included in the participating facilities because no clinic could be found that had been seeing a certain number of the same patients for 20 years. To avoid sampling bias, we enrolled up to 70 consecutive outpatients with schizophrenia attending each hospital from April 1, 2021, whose prescriptions could be traced over the past 20 years; for institutions that did not reach 70 patients, all patients were enrolled. Some patients have been hospitalized several times over the past 20 years. We retrospectively examined all prescriptions and hospitalizations as of April 1, 2016, 2011, 2006, and 2001, every 5 years starting in 2021, for this population. Consensus meetings were held at each site prior to the study to discuss issues related to data collection and the uniformity of data entry. The participating patients met the diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia in the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10)10 or the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5).11 Patients with clinically significant medical illnesses or active psychotic symptoms related to comorbid substance use disorders were excluded. In addition, exclusion criteria included neurological disorders such as dementia, concomitant organic psychiatric disorders, and severe intellectual disability. Patients were excluded if they had a condition that might take them outside of standard schizophrenia treatment. We excluded patients who had been off antipsychotic medication for more than two years in the past 20 years or who were untraceable because they had been treated at another hospital in the past 20 years.

The data collected included basic sociodemographic information and information on all prescribed medications. Data were obtained for 812 cases in total, but since there were 96 cases with missing data, 716 cases with complete data were included in the analysis. We defined FGA as the following 31 types of drugs that patients were taking during the 20-year period: bromperidol, carpipramine, chlorpromazine, clocapramine, clotiapine, fluphenazine, haloperidol, levomepromazine, moperone, mosapramine, nemonapride, oxypertine, perazine, perphenazine, pimozide, pipamperone, prochlorperazine, propericyazine, reserpine, spiperone, sulpiride, sultopride, thioridazine, tiapride, timiperone, thiothixene, trifluoperazine, zotepine, haloperidol decanoate, fluphenazine enanthate, and fluphenazine decanoate. SGA was defined as the following 13 types of drugs that the patients were taking during the 20-year period: aripiprazole, blonaserin, brexpiprazole, clozapine, lurasidone, olanzapine, paliperidone, perospirone, quetiapine, risperidone, asenapine, risperidone long-acting injection, and paliperidone palmitate. The rates of antipsychotic monotherapy were obtained by dividing the number of people treated with only one antipsychotic by all subjects. The rates of dual-agent antipsychotic use were obtained by dividing the number of people treated with two antipsychotic medications by all subjects. The rates of patients taking three or more drugs were obtained by dividing the number of people treated with three or more antipsychotic drugs in combination by all subjects. The complete monotherapy rate was defined as the rate of patients using only one antipsychotic drug and no other psychotropic drugs. Daily doses of antipsychotic drugs were calculated using the equations in the Inada & Inagaki article as average daily CPeq, imipramine equivalents, and diazepam equivalents.12

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Japanese Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects. Prior to the initiation of the study, the study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of the ethics committee of Dokkyo Medical University School of Medicine (Ref. R-54-3J). Since this was a retrospective medical record survey, it was exempted from the requirement for informed consent; however, we released information on this research so that patients were free to opt out. Administrative permissions and licenses were acquired by our team to access the data used in our research.

Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 28 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for analysis. The Cochran Q test and repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to determine the differences among the five groups. Although statistical significance required a two-sided P<0.05, these were adjusted by Bonferroni correction to avoid multiplicity, and P < 1.92×10−3 (0.05/26) was defined as significant. The Cochran–Armitage trend test was used to determine the trends. Statistical significance required a two-sided P<0.05.

Results

The mean (SD) age of the 716 patients in the study in 2021 was 61.7 (11.5) years; 51.0% (n=365) of patients were males, and 49.0% (n=351) were females. The proportion of patients with a history of hospitalization was 51.1% (n=366), and the number of hospitalizations ranged from 1–17, with a median of 3.

Trends of Antipsychotic Prescriptions

The rates of antipsychotic monotherapy in 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 and 2021 were 32.0%, 33.7%, 32.8%, 37.6% and 41.5%, respectively, with an increasing trend (χ2 = 16.3, df = 1, p = 5.4×10−5) (Table 1). The rates of dual-agent antipsychotic use were 36.7%, 37.4%, 39.4%, 41.9% and 41.9%, respectively. The rates of patients taking three or more antipsychotics were 18.7%, 18.5%, 18.0%, 14.0% and 9.4%, respectively. The rates of patients receiving complete antipsychotic monotherapy without psychotropic medications other than antipsychotics in 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 and 2021 were only 2.5%, 4.5%, 5.9%, 7.7% and 8.8%, respectively, with an increasing trend (χ2 = 32.3, df = 1, p = 1.3×10−8) (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Characteristics of Prescription in the Same Patients with Schizophrenia (N=715) |

The rates of SGA use in 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 and 2021 were 28.9%, 49.2%, 61.4%, 65.4% and 70.5%, respectively (Table 1 and Figure 1A), with an increasing trend (χ2 = 286.2, df = 1, p < 2.2×10−16). The rates of SGA monotherapy use in 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 and 2021 were only 9.1%, 16.3%, 18.9%, 23.2% and 29.3%, respectively (Table 1), with an increasing trend (χ2 = 102.5, df = 1, p < 2.2×10−16). The complete monotherapy rates for SGAs without other psychotropic medications in 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 and 2021 were only 0.7%, 2.7%, 3.5%, 5.0% and 6.3%, respectively (Table 1), with an increasing trend (χ2 = 37.6, df = 1, p = 9.0×10−10).

The rates of FGA use in 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 and 2021 were 85.6%, 77.5%, 70.7%, 65.1% and 54.7%, respectively (Table 1 and Figure 1A), with a decreasing trend (χ2 = 190.2, df = 1, p < 2.2×10−16). The rates of FGA monotherapy use in 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 and 2021 were 23.3%, 18.0%, 15.1%, 14.9% and 13.0%, respectively (Table 1), with a decreasing trend (χ2 =28.7, df = 1, p = 8.4×10−8). The complete monotherapy rates for FGA without other psychotropic medications in 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 and 2021 were 1.8%, 1.8%, 2.4%, 2.7% and 2.5%, respectively (Table 1) (Cochran Q = 2.05, df = 4, p = 0.728).

Trend of Dose of Antipsychotics

The average daily doses of SGAs prescribed to the patients increased from 432 mg to 559 mg (CPeq) over 20 years (Table 1 and Figure 1B). On the other hand, the average daily dose of FGAs prescribed to the patients decreased from 433 mg to 230 mg (CPeq) over 20 years (Table 1). The mean daily CPeq dose of all antipsychotics prescribed to the patients was unchanged (F = 2.24, df = 4, p = 0.062) over the past 20 years (Table 1 and Figure 1B).

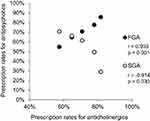

Trend of Concomitant Psychotropic Agents

The rates of concomitant use of anticholinergics in 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 and 2021 were 81.7%, 77.9%, 70.8%, 64.8% and 57.4%, respectively (Table 1), with a decreasing trend (χ2 = 133.4, df = 1, p<2.2x10−16) (Table 1). There was a significant negative correlation (r = −0.914, p = 0.030) between SGA and anticholinergic prescription rates (Figure 2) and a significant positive correlation (r = 0.993, p<0.001) between FGA and anticholinergic prescription rates (Figure 2). Those of antidepressants in 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 and 2021 were 7.3%, 7.8%, 8.2%, 7.5% and 8.2%, respectively (Cochran Q = 1.57, df = 4, p = 0.820) (Table 1). Those of anxiolytics/sleep medications in 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 and 2021 were 71.1%, 70.0%, 71.5%, 68.0% and 66.1%, respectively (Cochran Q = 15.2, df = 4, p = 0.04) (Table 1), but without any trend over the 20 years (χ2 = 4.86, df = 1, p = 0.028). Those of mood stabilizers and antiepileptics in 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 and 2021 were 19.1%, 23.3%, 25.7%, 24.4% and 21.9%, respectively (Cochran Q = 23.6, df = 4, p = 9.75×10−5) (Table 1), but there was no trend over the past 20 years (χ2 = 1.82, df = 1, p = 0.177).

Discussion

This study is the first in the world to follow the same patients with schizophrenia for 20 years in terms of the antipsychotics prescribed. The results of this study showed a slow but steady substitution of FGAs for SGAs over time. In addition, the rate of FGA monotherapy prescription was still quite high but decreased, whereas the rate of SGA monotherapy prescription gradually increased, but by less than half. The fact that SGA prescription has become mainstream since 2016, although this study did not incorporate new patients and, in 2001, SGA was not yet popular in Japan, so at this point in time, the study population was less likely to take SGA, may be due to the guidelines and other educational activities. This result is particularly positive even in Japan, a conservative country that favors multidrug therapy. In addition, although the dosage of the antipsychotics did not change, the ratio of SGAs to FGA dose was clearly elevated. This suggests that even if FGA was used in combination with SGA, the dosage would be kept small. Furthermore, this result is a corollary of the fact that SGA has replaced FGA as the mainstay of treatment, even for the same patients, over the past two decades.

Although guidelines recommend monotherapy with antipsychotics, the most frequently chosen treatment strategy internationally was combination antipsychotic therapy, prescribed in 49% of all patients.1,13 Combination antipsychotic therapy is recommended only as a last resort when clozapine has not been successful,14,15 although the use rate of clozapine is low in Japan.16 Despite these recommendations, adjunctive treatment strategies are often used in schizophrenia before trials of clozapine.17 Combination antipsychotic therapy is prescribed to 10–20% of outpatients, and as many as 50% of inpatients require two or more antipsychotics.18 Another study showed that combination antipsychotic therapy is prescribed to 10–20% of outpatients, and as many as 50% of inpatients require two or more antipsychotics. Furthermore, a study reported that combination therapy was prescribed to 42.5% of patients and augmentation therapy to 70% of patients.19 Combination therapy for schizophrenia in the “real world” may be aimed at enhancing the efficacy of antipsychotics and reducing side effects by utilizing the different receptor binding profiles of various medications.

The results of this study showed lower SGA and monotherapy rates than the results of other cross-sectional studies. The results of comparisons of combination antipsychotic therapy with monotherapy remain controversial. Combination antipsychotic therapy has shown little evidence of superior efficacy20,21 and is associated with a cumulative risk of adverse effects,22 pharmacokinetic interactions, mortality23 and increased costs compared with monotherapy.24

Because concomitant use of anticholinergic drugs has been associated with many problems in cognitive function and peripheral side effects, such as constipation and urinary retention,25,26 the guidelines recommend that anticholinergic drugs should not be used in combination. In this study, the results showed that the concomitant use rate and the average dosage used gradually decreased over a period of 20 years. This finding may reflect the increasing use of SGAs (Figure 2) and the increasing use of FGA (Figure 2), which have fewer extrapyramidal side effects, in addition to the widespread use of guidelines. These results were partially in line with our previous study using other samples.27

On the other hand, concomitant use of antidepressants increased even though antidepressants are not recommended by the guidelines. The addition of antidepressants to antipsychotic therapy for the treatment of schizophrenia is rather routine in clinical practice,28 but evidence on the efficacy of antidepressants is still limited and inconsistent.29 A recent comparative effectiveness study using US Medicaid national data found a reduced risk of psychiatric hospitalization and emergency room visits among outpatients with schizophrenia who were prescribed adjunctive antidepressants.30 In a recent meta-analysis, the concomitant use of antidepressants proved to be partially effective.14 Another factor may be that the widespread use of mirtazapine, which is less likely to cause side effects, instead of antidepressants such as tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which are more likely to cause activation syndrome, has reduced concerns about the concomitant use of antidepressants.

The prescribing rate of benzodiazepines did not change in this study. A recent systematic review did not test the efficacy of concomitant use of benzodiazepines with antipsychotics.29 Furthermore, a recent meta-analysis of 16 randomized controlled trials confirmed the lack of efficacy data.31,32 Therefore, in various guidelines, benzodiazepines were recommended for very short-term sedation of acutely agitated patients but not as an augmentation to antipsychotic therapy in the medium- to long-term pharmacotherapy of patients with schizophrenia and related disorders.

In a recent review, Carton et al estimated that 40–75% of all antipsychotic prescriptions are for off-label use.33 Mood disorders, anxiety disorders insomnia, and agitation were the main indications for antipsychotic use. A study in primary care in the United Kingdom found that a significant proportion of people prescribed antipsychotics had no record of psychosis or bipolar disorder, ie, the “classic” indications for antipsychotics.34 Similarly, only approximately 30% of antipsychotic prescriptions in Belgium were for psychotic disorders.35 In addition, a recent study of elderly patients in Taiwan suggested that approximately 80% of atypical antipsychotic users had a psychotic disorder, but only approximately 20% of typical antipsychotic users had a psychotic disorder. Only approximately 20% of atypical antipsychotic users had underlying psychiatric disorders.36 On the other hand, in our study, only schizophrenia was evaluated, the patients were followed in one hospital for 20 consecutive years, and the diagnosis and prescriptions were confirmed by their attending physicians. The findings from our study are more reliable than those of studies that include many patients who use antipsychotics for other psychiatric disorders.

There are several limitations to this study. First, our study looked at prescribing rates every 5 years; therefore, we cannot rule out the possibility that prescribing rates may have changed during the 5-year intervals. We also cannot rule out the possibility that the prescriptions were switched during that time. It is common in practice for patients to request to return to their original medications due to side effects after attempting to change to different medications. Second, in this study, we did not evaluate symptoms over a 20-year period. In particular, the analysis of various covariates needs to be considered, but it does not adequately pick up patient characteristics such as severity of illness and subgroups, which should help identify trends. Therefore, the causal relationship between the reason for change and the change in prescription cannot be clarified because it is unclear whether the change in prescription was due to unchanged symptoms or side effects. Third, important information is missing, such as the age of the physician prescribing the medication (younger physicians tend to have less experience with FGAs), which SGA or FGA is used more frequently, preference trends, patient complications, and reasons for switching. Finally, there is a bias in that patients who were transferred to other hospitals or died during the 20-year study period were not tracked, which is called panel mortality. In addition, this study was retrospective in design, whereas in the majority of published studies, panel studies were performed prospectively. The retrospective design of the study was because only the past trends in prescribing rates were investigated. In the future, prospective trend studies and cohort studies are necessary.

In conclusion, the results of this study showed a slow but steady substitution of SGAs for FGAs over time, even in the same patients. However, monotherapy with SGA has remained low, albeit with a slight upward trend. The rates of concomitant use of anticholinergics decreased, but those of antidepressants, anxiolytics/sleep medications, and mood stabilizers were unchanged.

Data Sharing Statement

Although the data underlying the study’s findings are anonymized, they contain potentially identifying or sensitive patient information. Under the ethical restrictions and legal framework of Japan, the data are unsuitable for public deposition. Please contact the Ethics Committees of Dokkyo Medical University School of Medicine and Hirosaki University School of Medicine, which have set restrictions on data sharing. Upon request, the ethics committees will assess whether researchers meet the criteria for access to confidential data.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. Kazuyoshi Kawai for his invaluable assistance.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclosure

Dr. Kensuke Miyazaki reports personal fees from Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co., Ltd., outside the submitted work. Professor Kazutaka Shimoda reports grants from Novartis Pharma KK, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma Co., Astellas Pharma Inc., Meiji Seika Pharma Co., Ltd., Eisai Co., Ltd., Pfizer Inc., Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Daiichi Sankyo Co., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; personal fees from Eisai Co., Ltd, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Meiji Seika Pharma Co., Ltd., Janssen Pharmaceutical Co., Shionogi & Co. Ltd., Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma Co., Daiichi Sankyo Co., and Pfizer Inc., outside the submitted work. The remaining authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Buchanan RW, Kreyenbuhl J, Kelly DL, et al. The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychopharmacological treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:71–93. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbp116

2. Hasan A, Wobrock T, Gaebel W, et al. Germany Society of Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics (DGPPN); German Association of Psychiatry. Nervenarzt. 2013;84:1359–60, 1362–4, 1366–8. doi:10.1007/s00115-013-3913-6

3. NICE. Psychosis and Schizophrenia in Adults: The NICE Guideline on Treatment and Management. NICE Clinical Guideline 178; 2014. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178.

4. Remington G, Addington D, Honer W, et al. Guidelines for the Pharmacotherapy of Schizophrenia in Adults. Can J Psychiatry. 2017;62:604–616. doi:10.1177/0706743717720448

5. Japanese Society of Neuropsychopharmacology. Japanese Society of Neuropsychopharmacology: “Guideline for Pharmacological Therapy of Schizophrenia”. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep. 2021;41:266–324. doi:10.1002/npr2.12193

6. Halfdanarson O, Zoega H, Aagaard L, et al. International trends in antipsychotic use: a study in 16 countries, 2005-2014. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;27:1064–1076. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2017.07.001

7. Toto S, Grohmann R, Bleich S, et al. Psychopharmacological Treatment of Schizophrenia Over Time in 30 908 Inpatients: data From the AMSP Study. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019;22:560–573. doi:10.1093/ijnp/pyz037

8. Lindenmayer JP, Czobor P, Volavka J, et al. Olanzapine in refractory schizophrenia after failure of typical or atypical antipsychotic treatment: an open-label switch study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63::931–5. doi:10.4088/JCP.v63n1011

9. Pae CU, Chiesa A, Mandelli L, Patkar AA, Gibiino S, Serretti A. Predictors of early worsening after switch to aripiprazole: a randomized, controlled, open-label study. Clin Drug Investig. 2010;30:187–193. doi:10.2165/11533060-000000000-00000

10. Keith SJ, Matthews SM. The diagnosis of schizophrenia: a review of onset and duration issues. Schizophr Bull. 1991;17:51–67. doi:10.1093/schbul/17.1.51

11. Tandon R, Gaebel W, Barch DM, et al. Definition and description of schizophrenia in the DSM-5. Schizophr Res. 2013;150:3–10.

12. Inada T, Inagaki A. Psychotropic dose equivalence in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;69:440–447. doi:10.1111/pcn.12275

13. Lehman AF, Kreyenbuhl J, Buchanan RW, et al. The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT): updated treatment recommendations 2003. Schizophr Bull. 2004;30:193–217.

14. Conley RR, Kelly DL. Management of treatment resistance in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50:898–911. doi:10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01271-9

15. Moore TA, Buchanan RW, Buckley PF, et al. The Texas Medication Algorithm Project antipsychotic algorithm for schizophrenia: 2006 update. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1751–1762. doi:10.4088/jcp.v68n1115

16. Yasui-Furukori N, Muraoka H, Hasegawa N, et al. Association between the examination rate of treatment-resistant schizophrenia and the clozapine prescription rate in a nationwide dissemination and implementation study. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep. 2022;42:3–9. doi:10.1002/npr2.12218

17. Buchanan RW, Kreyenbuhl J, Zito JM, et al. Relationship of the use of adjunctive pharmacological agents to symptoms and level of function in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1035–1043.

18. Stahl SM, Grady MM. A critical review of atypical antipsychotic utilization: comparing monotherapy with polypharmacy and augmentation. Curr Med Chem. 2004;11:313–327. doi:10.2174/0929867043456070

19. Pickar D, Vinik J, Bartko JJ. Pharmacotherapy of schizophrenic patients: preponderance of off-label drug use. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3150. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003150

20. Freudenreich O, Goff DC. Antipsychotic combination therapy in schizophrenia. A review of efficacy and risks of current combinations. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;106:323–330. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.01331.x

21. Stahl SM. Antipsychotic polypharmacy: evidence-based or eminence based? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;106:321–322. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.2e011.x

22. Correll CU, Frederickson AM, Kane JM, et al. Does antipsychotic polypharmacy increase the risk for metabolic syndrome? Schizophr Res. 2007;89:91–100. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2006.08.017

23. Joukamaa M, Heliovaara M, Knekt P, et al. Schizophrenia, neuroleptic medication and mortality. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:122–127. doi:10.1192/bjp.188.2.122

24. Stahl SM. Antipsychotic polypharmacy: squandering precious resources? J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:93–94. doi:10.4088/jcp.v63n0201

25. Georgiou R, Lamnisos D, Giannakou K. Anticholinergic burden and cognitive performance in patients with schizophrenia: a Systematic Literature Review. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:779607.

26. Rodríguez-Ramallo H, Báez-Gutiérrez N, Prado-Mel E, et al. Association between Anticholinergic Burden and Constipation: a Systematic Review. Healthcare. 2021;9:581. doi:10.3390/healthcare9050581

27. Hori H, Yasui-Furukori N, Hasegawa N, et al. Prescription of Anticholinergic Drugs in Patients With Schizophrenia: analysis of Antipsychotic Prescription Patterns and Hospital Characteristics. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:823826. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.823826

28. Zink M, Englisch S, Meyer-Lindenberg A. Polypharmacy in schizophrenia. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2010;23:103–111.

29. Hinkelmann K, Yassouridis A, Kellner M, et al. No effects of antidepressants on negative symptoms in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33:686–690.

30. Stroup TS, Gerhard T, Crystal S, et al. Comparative effectiveness of adjunctive psychotropic medications in patients with schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76:508–515. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.4489

31. Sim F, Sweetman I, Kapur S, et al. Re-examining the role of benzodiazepines in the treatment of schizophrenia: a systematic review. J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29:212–223. doi:10.1177/0269881114541013

32. Dold M, Li C, Gillies D, Leucht S. Benzodiazepine augmentation of antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis and Cochrane review of randomized controlled trials. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23:1023–1033. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.03.001

33. Carton L, Cottencin O, Lapeyre-Mestre M, et al. Off-Label prescribing of antipsychotics in adults, children and elderly individuals: a systematic review of recent prescription trends. Curr Pharm Des. 2015;21:3280–3297. doi:10.2174/1381612821666150619092903

34. Marston L, Nazareth I, Petersen I, et al. Prescribing of antipsychotics in UK primary care: a cohort study. BMJ open. 2014;4:e006135-2014–006135. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006135

35. Morrens M, Destoop M, Cleymans S, et al. Evolution of first-generation and second-generation antipsychotic prescribing patterns in Belgium between 1997 and 2012: a population-based Study. J Psychiatr Pract. 2015;21:248–258. doi:10.1097/PRA.0000000000000085

36. Kuo CL, Chien IC, Lin CH. Trends, correlates, and disease patterns of antipsychotic use among elderly persons in Taiwan. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2016;8:278–286. doi:10.1111/appy.12230

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.