Back to Journals » Advances in Medical Education and Practice » Volume 12

Ongoing Value and Practice Improvement Outcomes from Pediatric Palliative Care Education: The Quality of Care Collaborative Australia

Authors Slater PJ , Osborne CJ, Herbert AR

Received 20 August 2021

Accepted for publication 28 September 2021

Published 10 October 2021 Volume 2021:12 Pages 1189—1198

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S334872

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Prof. Dr. Balakrishnan Nair

Penelope J Slater,1 Caroline J Osborne,1 Anthony R Herbert2,3 On behalf of the Quality of Care Collaborative Australia

1Oncology Services Group, Queensland Children’s Hospital, Children’s Health Queensland, South Brisbane, Queensland, Australia; 2Paediatric Palliative Care Service, Queensland Children’s Hospital, Children’s Health Queensland, South Brisbane, Queensland, Australia; 3Centre for Children’s Health Research, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia

Correspondence: Penelope J Slater

Oncology Services Group, 12b, Queensland Children’s Hospital, 501 Stanley Street, South Brisbane, Queensland, 4101, Australia

Tel +61 7 3068 5785

Fax +61 7 3068 4139

Email [email protected]

Purpose: Novice and experienced professionals who care for children with life limiting conditions throughout Australia were provided with pediatric palliative care (PPC) education through the Quality of Care Collaborative Australia (QuoCCA). Impact evaluation has shown this education to be beneficial. This study examines the longer term outcomes reported by the participants more than 4 months following education.

Methods: An online survey measuring quantitative and qualitative education outcomes was sent to all participants of QuoCCA 2 education throughout Australia, at least 4 months following their education. There were 152 respondents between February 2018 and June 2020.

Results: More than 4 months after the QuoCCA education, 98% of respondents rated it as extremely valuable or valuable and 78% of respondents rated it extremely or very helpful in improving clinical practice. Improvements in knowledge, skills or confidence were reported by 90% or more respondents in the areas of PPC referral, responding to psychosocial needs, the benefits of the PPC approach, PPC resources and communication skills. Between 84% and 89% of respondents reported improvements in advance care planning, assessment and intervention, responding to physical needs, supporting spiritual needs and supporting health professionals and self care. Providing bereavement care improved in 85% of responses. The most valuable aspects of the education, changes in practice and barriers to the implementation of learning were discussed.

Conclusion: The interprofessional QuoCCA education in PPC continued to provide value and clinical practice improvements for the majority of respondents more than four months after the session. Respondents particularly mentioned improvements in awareness of the network of care, the practical management of patients and communication skills. Reflection on clinical practice, in a proactive clinical learning environment, enabled the translation of education into improvements to the quality of PPC.

Keywords: education outcomes, evaluation, practice improvements, medical education, palliative care

Introduction

The Quality of Care Collaborative Australia (QuoCCA), funded through the Australian Government Department of Health’s National Palliative Care Projects, has been rolling out education in pediatric palliative care (PPC) throughout Australia since May 2015. A learning needs analysis was conducted with Queensland multidisciplinary health professionals in 2016.1 The top learning needs were used to develop the QuoCCA continuous practice development curriculum, and ongoing evaluation and refinement achieved national harmonization of the curriculum.2

For the first three-year round of funding, 337 education sessions were completed around Australia by QuoCCA funded educators based in tertiary PPC services in Brisbane, Melbourne, Adelaide and Perth; involving 767 hours of education and 5773 participants. Regional and remote locations received 40% of the QuoCCA education sessions. Its versatility was demonstrated through successful implementation in a wide range of settings from home visits with families, hospital rooms, meeting rooms, staff rooms and lecture halls. The education was sometimes didactic, but also involved a large amount of interactive group work, discussing case studies, mentoring and follow up support.2

Impact evaluation has shown immediate benefits of QuoCCA education for both novice and experienced professionals who care for children with a life limiting condition and their families.2 There were significant improvements in scores of all self-reported measures collected immediately following education. Dosage of education drove improvements in knowledge, skills and confidence; in that repeated and longer education sessions with previous palliative care experience produced a greater effect. Education tailored to the needs of the participants and interactive education that included storytelling, case studies and parent experiences was more effective.2

Interviews with QuoCCA participants and educators emphasised the importance of building capacity in pediatric palliative care and developing inter-professional relationships through building networks, establishing communication pathways and ongoing mentoring.3 Learning from children and families was of special significance for health professionals; as family centered care is a core principle of PPC.

With these encouraging results, after the project commenced its second round of 3-year funding (QuoCCA 2), it was pertinent to investigate the longer term outcomes of the education for the participants. A review of long term retention of medical education showed that learning can be quickly lost in the months following education unless there is opportunity to practice and apply it in the clinical setting.4 The objectives of this study were to survey QuoCCA participants more than 4 months following their education, to determine the ongoing value of the education, if it had made a difference to their practice in caring for PPC patients, the barriers that existed to applying the education, their self-reported improvement in knowledge, skills or confidence, and other topics they would like to see in future education.

Method

Between July 2017 to June 2020, 449 QuoCCA 2 education sessions were delivered to 7152 participants over 901 hours, including 209 scheduled and 185 pop up education sessions (as well as 60 incidental sessions). Scheduled education was pre-planned general PPC education which addressed the needs of the participants and was delivered in any location. Pop up education was related to the care of a specific patient, supporting local services away from a tertiary center to care for the child and family. In this education type, a small interprofessional team of health professionals travelled to a center to deliver education, responding in a timely way to patient/family needs.5 Each participant was invited to complete an impact survey immediately following education and provide their email address on an attendance list to enable follow up via the survey for this study.

Between February 2018 and June 2020, an online survey measuring quantitative and qualitative education outcomes was emailed to all participants of QuoCCA 2 education throughout Australia, at least 4 months following their education. Inclusion criteria were professionals who had registered and attended the QuoCCA 2 education, had supplied their email to be contacted for further evaluation, and were over the age of 18. The sampling involved emailing 3929 participants during that time and all responses received were included in the study. As people moved roles some participants were more difficult to contact, and some email addresses were followed up through phone calls and internet searches. Participants who had a common statewide email system, such as government emails, were easier to trace.

Questions in the survey are shown in Table 1. Quantitative questions were scored with a Likert scale. The scores for the value of the education were: no value, minimal value, neutral, valuable and extremely valuable. Helpfulness of education in improving self efficacy related to knowledge, skills or confidence in PPC were scored as: not at all, a little, moderately, very, or extremely helpful, not applicable for me and not covered in the session. Survey validity was facilitated through the use of questions and constructs used through the QuoCCA impact evaluation from 2015, as well as the use of recognised areas of PPC that were used in the evaluation of the Program of Excellence in Palliative Approach (another national project).6 Some open qualitative questions provided a greater insight into the responses, information on barriers and suggested future topics. The survey results were exported and descriptive statistics constructed through Microsoft Excel and chi-squared tests of independence conducted between proportions. The location of respondents was classified according to the Australian Statistical Geographical Classification - Remoteness Area 2016.7

|

Table 1 The Questions Included on the QuoCCA Outcome Survey |

The 152 respondents came from Queensland (n=79), Western Australia (19), South Australia (16), Victoria (15) and 22 from other states visited by QuoCCA educators (8 in Tasmania, 6 in Australian Capital Territory, 6 in New South Wales and 2 in Northern Territory).

The protocol for the evaluation of this national collaborative in education was approved by the Children’s Health Queensland Human Research and Ethics Committee (HREC/16/QRCH/60/AM02). Participants were provided with information about the project, including that participation was voluntary and the results were confidential, and they provided informed consent, which included publication of anonymized responses, in completion of the questionnaires.

Results

There were 152 respondents to the survey between February 2018 and June 2020, 71% who had received education less than 1 year prior, and 29% had education more than a year prior. Survey responses occurred throughout the period of the study, including 24% in 2018, 46% in 2019 and 30% in 2020 (to end of June). Respondents were 67% nursing, 13% allied health, 9% medical and 12% administration/other. The 2018 national registered health workforce in Australia included 57% nurses, 23% allied health and 17% medical,8 which demonstrates an over-representation of nurses in survey respondents (chi squared p<0.05), which is also seen in the specialist palliative care workforce.9 Respondents worked in various roles including public health services (81%), private health services (3%), general practice (1%) and other areas (16%).

As there had been close collaboration between the QuoCCA Educators from 2015 in the development of education modules and methods, this ensured harmonization of education throughout the country and enabled comparison of respondents from different states.

The respondents were located in major city (47%), inner regional (28%), outer regional (17%), remote (5%) and very remote (3%) areas. These proportions were not significantly different to those of the total QuoCCA 2 participants (chi-squared test p = 0.22).

Of the different QuoCCA education types, the respondents had attended scheduled education sessions (74%), pop up sessions (22%), both pop up and scheduled education sessions (1%), and other sessions (2%).

Value of Education

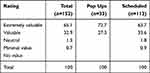

Despite the passing of some time since the education, it was still highly valued, with 98% of respondents rating it extremely valuable or valuable (Table 2). There was no significant difference in the rating of value reported by occupation (medical, nursing, allied health, administration or other; chi-squared p=0.28). A greater percentage of attendees of pop up education found it extremely valuable (73% of pop up versus 64% of scheduled attendees) however, this was not a significant difference (chi-squared p = 0.43).

The follow up question was “What were the most valuable aspects of the QuoCCA education session?” Table 3 shows the most valuable aspects were building the relationship with the tertiary PPC service and knowing about the support they provided as well as the general information about PPC. Presentation and discussion of case studies continued to be a valuable mode of education. The team building resulting from the QuoCCA education session was valuable as the respondents found out more about the local resources and services available for families and helped them approach the care of the child as a multidisciplinary team.

|

Table 3 Top 20 Themes from 139 Responses Related to the Most Valuable Aspects of the QuoCCA Education |

Making a Difference to Practice

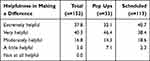

In total, 78% of respondents stated that the QuoCCA education session was extremely or very helpful in making a difference to their practice in caring for patients, at the same level for pop ups or scheduled sessions (chi-squared p=0.50) (Table 4). The responses were dependent upon occupation (chi squared p = 0.025), mostly due to a greater proportion of nurses finding the education extremely helpful in changing their practice. The percentage of responses of “extremely helpful” varied from 70% for nursing, 60% for other (including educators, chaplains and administration staff), 55% for allied health and 53% for medical.

|

Table 4 Percentage of Responses for the Question “How Helpful Overall Was the QuoCCA Education in Making a Difference to Your Practice in Caring for Pediatric Palliative Patients?” by Education Type |

The follow up question was “If QuoCCA education has made a difference to your practice and care of patients and families, describe this.” Themes in these self-reported changes in practice are shown in Table 5. Again, it made a difference for the care team to know the local and statewide services and resources available, and the education provided an opportunity to improve collaboration, communication and understanding of roles between those services. Also improved was early referral to, and awareness of, the support provided by the tertiary PPC service (PPCS). Generally, respondents reported increased knowledge, skills and confidence in caring for the patient and supporting the family. Respondents were able to offer better patient centered care, with empathy and compassion. Many respondents had improved their communication with families, being able to listen better, answer difficult questions and normalise PC for families. The practical side of care had also improved, such as symptom management, care planning, and spending quality time with patients. Some quotes are shown below:

As a regional facility with limited experience with pediatric palliative care, the QuoCCA education is very important for awareness, enhancement and equipping staff with information and knowledge gained from education.

More knowledgeable so can educate parents better and have a better understanding of the service our children and families are involved in. I now see this service as a positive thing for parents instead of a thing to be afraid of and can encourage them to be involved with the service where appropriate.

This education came when I was involved in the care of a palliative patient, this being the second palliative pediatric patient I had been involved with. The education really helped to break down barriers in discussing palliation of children, and I had a better idea of what to expect and how the patient would be managed. The training gave me more confidence in communicating with the parents at an extremely difficult time for them.

|

Table 5 Top 20 Themes from 109 Responses Related to Changes to Practice as a Result of the QuoCCA Education |

Barriers to Applying the Education

Respondents provided some insights into the barriers of applying the education (Table 6). These were mostly around the rarity of cases requiring PPC, time constraints and lack of resources. Four respondents reported PC being a taboo subject for clinicians and having a stigma for families, leading to reluctance or delay in referral. Others referred to a lack of coordination of care between services, including the multidisciplinary team and the general practitioner. Another respondent mentioned the barrier of their own emotions. Some quotes are show below:

Death and dying is a taboo subject that few really want to discuss. More education is needed and especially the doctors. We need to make families more aware of what we can do to support them.

I have previously had difficulty getting medical teams to commence palliative care earlier than just prior to death; still find certain teams reluctant to see palliative care's bigger roles.

|

Table 6 Themes from 46 Responses Related to Barriers in Applying QuoCCA Education |

Improvement in Knowledge, Skills and Confidence

Improvements in self efficacy related to knowledge, skills or confidence were reported by more than 90% of respondents regarding PPC referral, responding to psychosocial needs, the benefits of the PPC approach, PPC resources and communication skills (Table 7). Between 84–89% of respondents reported improvements in advance care planning, assessment and intervention, responding to physical needs, supporting spiritual needs, providing bereavement care and supporting health professionals and self care. There was no significant difference between pop up and scheduled sessions for any of these results (chi-squared p>0.05).

Future Education

Respondents provided suggestions for future education topics (Table 8). The most popular were symptom/pain management, ethics and case study discussions.

|

Table 8 Top 20 Themes Related to Topics That Responders Would Like to See in Future Sessions (40 Responders) |

General Comments

Some general comments from respondents are included below:

This was a terrific session and was taught by very knowledgeable and helpful presenters.

This is a wonderful service and has been very beneficial to our pediatric ward team and families in palliative care. I believe that it is vital to have this education available to regional areas who otherwise would not receive any education.

I found both sessions extremely informative and really helped me when working with our palliative care families.

It was good to be participate in that education alongside my team, and for them to have confidence in my knowledge, skills and ability to lead them in caring for this child.

Discussion

This paper has shown longer term positive outcomes of an interprofessional educational intervention in PPC. It explored how the education facilitated these outcomes and what barriers existed to applying the learnings in the workplace. There was value related to both pop up education supporting the management of specific patients and for scheduled education applied to the general context of the service. A large majority of the respondents in this study reported ongoing value and improvements to clinical practice, similar to other studies that showed benefits of education in palliative care up to 4 years after the education.10 Nursing staff reported a slightly higher level of helpfulness of the QuoCCA education in making a difference to their practice, and this may be a reflection of greater system flexibility for nurses both individually and organizationally to be able to apply these new learnings. As the majority of QuoCCA education sessions were led by nurse educators, it may also reflect that bias in the material presented.

An important value provided through QuoCCA education was to raise awareness of the local and statewide network of professionals and resources and improving relationships between them. QuoCCA participants included hospital based and community health professionals, education providers, funeral services, ambulance services and pastoral carers. These networks of care encouraged informal working relationships based on collegiality and common goals of care. They have been found to assist in the delivery of coordinated care and help individual services to maintain quality of care through combined education and regional service development.11 Respondents in this study also reported that practice improvements resulted from this increased knowledge of the network of care.

Respondents found value in being educated about the delivery of holistic palliative care, especially through examples provided from case studies, sharing experiences and discussing issues, boundaries and ethics. Education on practical symptom management also provided high value.

Practice improvements arising from the education included improved communication skills with patients and families, increased confidence in caring for these families, insights into meeting the families’ needs, and a general increase in knowledge, skills and understanding of practical management of the patients. Communication skills were often taught through skills practice (eg role play), videos of clinical interactions, and case-based studies. Experiential learning, and reflection upon such experiences, lead to improvements in both confidence and capacity to provide palliative care, supporting patients and families and providing compassionate communication.12

There were some barriers to improving PPC practice following the education, mostly due to the very small number of cases that were seen in regional areas. When a patient was present, there were constraints around time, rostering and resources that prevented the respondents applying their new practice knowledge. This low-frequency but high-need situation encouraged a focus on the more responsive pop up education in regional areas, as it provided very relevant education to a team who was highly involved with a patient and motivated to learn.

The stigma of PPC for families and a reluctance to refer by the families and the medical professionals resulted in late PPC referrals and reduced service provision in regional areas. There was a need for increased awareness of the contribution of PPC to support families, and tertiary PPC services to support local staff. The respondents reported an emotional toll of being involved in the PPC cases, highlighting the importance of ongoing support for sustainable practice through the tertiary team and local wellbeing strategies.

Similar barriers to implementation were found in general nursing education in Australia, including changing staff practices and culture, sufficient time, a combination of work-related issues and hospital procedures and policy.13 Even if participants were motivated to implement their learnings from QuoCCA education when they returned to their workplaces, the barriers may be beyond their control. Collaboration between education participants and their managers to proactively plan for translation of learnings to practice, and ongoing coaching and support would be beneficial.13 Workplace mentoring could also be facilitated through a network of subject champions, such as the Lead Pediatricians and Regional Case Managers that have been situated in Regional Shared Care Units through the Queensland Paediatric Palliative care, Haematology and Oncology Network since 2016.14 They work in close collaboration with the tertiary children’s hospital and train and mentor staff in their hospital and smaller regional hospitals, where a champion model may be useful.15,16

Through the progressive QuoCCA projects since 2015, the aim has been to evaluate the effectiveness of education by assessing it at all levels using Kirkpatrick’s Model17 based on a project logic.2,18 Outputs were measured from QuoCCA education reports around Australia. As health professionals were the direct QuoCCA client, we have evaluated the impacts of QuoCCA through their level of satisfaction and changes in knowledge and attitudes.2,3 This paper has reported on longer term outcomes through assessment of value and self reported practice changes following QuoCCA education. A future paper will also report on the impacts and outcomes of mentoring of medical fellows and nurse practitioner candidates through involvement in QuoCCA.

The ultimate measure of the project success is related to patient/family outcomes, via the quality of care provided by health/human service professionals to children and families. When the target of the evaluation is further away from the actual participants, it becomes more difficult to demonstrate a causal link. However, the QuoCCA collaborative is currently reviewing interviews from families who have received pop up education around their palliative care needs. This evaluation will take into account individualised care and the unique experience of each family in the context of the seamless provision of services to a uniform standard across the state. The family experiences will inform gaps that may exist in education aligned to the wide range of family needs. It would also be possible to expand on the interviews of education participants regarding how involvement in the QuoCCA collaboration and education has impacted outcomes for children and families in their area.2 The addition of a reconciliation of the learning needs analysis would complete this picture.1 It is recommended that the future development of QuoCCA education will include co-design, analysis and interpretation with stakeholders to allow deeper evaluation of how the education has met their needs.19 The Jacobs’ Model17,20 recommended the use of the context and policy framework, the goals, and stakeholder consultation to inform the evaluation. The fulfilment of the National Palliative Care Strategy 2018 would be important in this context.21

The QuoCCA Outcomes Survey was designed to measure the participant’s self-reported value in the QuoCCA education and any resulting changes in clinical practice. Positive impact may only be truly demonstrated by actual measured change in behavior in the clinical area.22,23 To demonstrate a causal relationship between the QuoCCA education and clinical practice improvement, a complex array of variables would need to be controlled. However, self-reported education value can be a proxy for long term satisfaction with the education, and self-reported practice improvements can be considered a proxy to increased clinician self-efficacy in delivering PPC care. Both are important outcomes of the QuoCCA education.

In what ways were QuoCCA education participants supported to translate their learnings to improvements in the quality of their practice? The QuoCCA Educators had previously reported that participants learnt more effectively with interactive techniques and methods such as storytelling, case studies and parent experiences.2 The respondents in this study cited excellent education provided by knowledgeable and experienced presenters, creating a relationship with the tertiary team from whom they received ongoing support and mentoring, having access to resources and attending the education as a team. Although this study showed that both pop up and scheduled education were extremely valuable and improved the participants’ knowledge, skills and confidence; anecdotally, pop up education related to a real case with an in-time response to an educational need was a very powerful mode of education. This will be investigated in more detail by the QuoCCA collaborative.

A key domain of core competencies for education in PPC is professional practice; including research, evaluation, policy and training and education.24 It is important to teach the skills of quality improvement and to ensure health professionals undertake self- directed lifelong learning to improve their ability to cope with complexities and uncertainties through clinical reasoning.25,26 For continued improvement in the quality of their practice, the PPC education participants would benefit from increased competency in reflective practice, lifelong learning, service evaluation and research, to continue to apply what they have learnt on both an individual and service level.

A study of ward nurse perceptions of continuing education found they “yearned for changes to facilitate lifelong learning and cultivate a learning culture”.27 The participants’ organizational environment needs to take advantage of that motivation of clinicians to improve their practice. The development of clinical learning environments would support the improvement of quality of care.28

Evaluation processes following education have been shown to trigger participants to reflect on their practice.13 It is hoped that the follow up evaluation of QuoCCA education assisted participants to reflect on how to improve their service and translate the QuoCCA learnings to the care of patients and families. Education has long term value when the clinicians are enabled to drive positive change from what they have learnt. Reflection on clinical practice as an outcome of education, in a proactive clinical learning environment, are important enablers for the translation of education into improvements to the quality of PPC care for patients and families.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank the respondents in this study for their input around the value that pediatric palliative care education had provided. We also thank the QuoCCA Educators throughout Australia for their dedication in providing this education and collecting data that supports the ongoing evaluation of the project, and the members of the Collaborative: Sarah Baggio, Leigh Donovan, Alison McLarty, Julie Duffield, Lee-Anne Pedersen, Kerry Gordon, Jacqueline Duc, Angela Delaney, Susan Johnson, Melissa Heywood, Charlotte Burr, Sara Fleming, Jenny Hynson, Marianne Phillips, Sharon Spence, Lisa Cuddeford, Suzanne Momber, Sharon Ryan, Susan Trethewie and Ashka Jolly.

Funding

The QuoCCA Project was undertaken through Australian Government Department of Health funding provided from the National Palliative Care Projects operating under the Chronic Disease Prevention and Service Improvement Fund, grant funding round H1314G012.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflict of interest in this work.

References

1. Baggio S, Herbert A, Delaney A, et al. A national quality of care collaboration to improve paediatric palliative care outcomes.

2. Slater PJ, Herbert AR, Baggio SJ, et al.; on behalf of Quality of Care Collaborative Australia. Evaluating the impact of national education in pediatric palliative care: the Quality of Care Collaborative Australia. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2018;9:927–941. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S180526

3. Donovan LA, Slater PJ, Baggio SJ, McLarty AM, Herbert AR; on behalf of Quality of Care Collaborative Australia. Perspectives of health professionals and educators on the outcomes of a national education project in pediatric palliative care: the Quality of Care Collaborative Australia. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2019;10:949–958. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S219721

4. Butler AC, Raley ND. The future of medical education: assessing the impact of interventions on long-term retention and clinical care. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(3):483–485. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-15-00236.1

5. Mherekumombe MF, Frost J, Hanson S, Shepherd E, Collins J. Pop Up: a new model of paediatric palliative care. J Paediatr Child Health. 2016;52(11):979–982. doi:10.1111/jpc.13276

6. Program of excellence in the palliative approach. [Homepage on the internet]. Brisbane: PEPA Education; 2021. Available from: https://pepaeducation.com.

7. Commonwealth of Australia. Department of Health. [homepage on the Internet]. Australian statistical geography standard - Remoteness area. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2019. Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/health-topics/health-workforce/health-workforce-classifications/australian-statistical-geographical-classification-remoteness-area.

8. Health workforce. Snapshot. [Homepage on the internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2021. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/health-workforce.

9. Palliative care services in Australia. Palliative care workforce. [Homepage on the internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2021. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/palliative-care-services/palliative-care-services-in-australia/contents/palliative-care-workforce.

10. Fortin Magaña M, Diaz S, Salazar-Colocho P, et al. Long-term effects of an undergraduate palliative care course: a prospective cohort study in El Salvador. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2020:

11. Spruyt O. Team Networking in Palliative care. Indian J Palliat Care. 2011;17(4):S17–S19. doi:10.4103/0973-1075.76234

12. Yates P, Clinton M, Hart G. Improving psychosocial care: a professional development programme. Int J Palliat Nurs. 1996;2(4):212–215. doi:10.12968/ijpn.1996.2.4.212

13. Wellings CA, Gendek MA, Gallagher SE. Evaluating continuing nursing education. A qualitative study of intention to change practice and perceived barriers to knowledge translation. J Nurses Prof Dev. 2017;33(6):281–286. doi:10.1097/NND.0000000000000395

14. Slater PJ. Supporting collaborative care - The Queensland paediatric palliative care, haematology and oncology network.

15. Engel M, van Zuylen L, van der Ark A, van der Heide A. Palliative care nurse champions’ views on their role and impact: a qualitative interview study among hospital and home care nurses. BMC Palliat Care. 2021;20(1):34. doi:10.1186/s12904-021-00726-1

16. Kamal AH, Bowman B, Ritchie CS. Identifying palliative care champions to promote high-quality care to those with serious illness. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(S2):S461–S467. doi:10.1111/jgs.15799

17. Kirkpatrick D. The four levels of evaluation. In: Brown S, Seidner C, editors. Evaluating Corporate Training: Models and Issues. Norwell, MA: Kluwer Academic; 1998:95–112.

18. Centre for Epidemiology and Evidence. Developing and Using Program Logic: A Guide. Evidence and Evaluation Guidance Series, Population and Public Health Division. Sydney: NSW Ministry of Health; 2017.

19. Vassar M, Wheller DL, Davison M, Franklin J. Program evaluation in medical education: an overview of the utilization- focused approach. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2010;7:1. doi:10.3352/jeehp.2010.7.1

20. Jacob C. The evaluation of education innovation. Evaluation. 2000;6(3):261–280. doi:10.1177/13563890022209280

21. Australian Government. National Palliative Care Strategy 2018. Canberra: Department of Health; 2019.

22. Heick MA. Continuing education impact evaluation. J Cont Educ Nurs. 1981;12(4):15–23. doi:10.3928/0022-0124-19810701-04

23. Ellis LB. Evaluating the effects of continuing nurse education on practice: researching for impact. Cont Nurs Educ. 1996;1(4):296–305.

24. Downing J, Ling J, Benini F, Payne S, Papadatou D. A summary of the EAPC white paper on core competencies for education in paediatric palliative care. Eur J Palliat Care. 2014;21(5):245–249.

25. Rosenberg ME. An outcomes-based approach across the medical education continuum. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2018;129:325–340.

26. Jones R. Medical education research: evidence, evaluation and experience. Educ Prim Care. 2019;30(6):331–332. doi:10.1080/14739879.2019.1687336

27. Govranos M, Newton JM. Exploring ward nurses’ perceptions of continuing education in clinical settings. Nurs Educ Today. 2014;34(4):655–660. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2013.07.003

28. Ferguson A. Evaluating the purpose and benefits of continuing education in nursing and the implications for the provision of continuing education for cancer nurses. J Adv Nurs. 1994;19:640–646. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.1994.tb01133.x

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.