Back to Journals » Advances in Medical Education and Practice » Volume 12

Longitudinal Outcome of Programmatic Assessment of International Medical Graduates

Authors Parvathy MS, Parab A, R Nair BK , Matheson C, Ingham K, Gunning L

Received 15 June 2021

Accepted for publication 8 September 2021

Published 23 September 2021 Volume 2021:12 Pages 1095—1100

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S324412

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Md Anwarul Azim Majumder

Mulavana S Parvathy,1,2 Aditee Parab,3 Balakrishnan Kichu R Nair,1– 3 Carl Matheson,4 Kathy Ingham,1 Lynette Gunning1

1Centre for Medical Professional Development, Hunter New England Local Health District, Newcastle, NSW, Australia; 2School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, Newcastle, NSW, Australia; 3John Hunter Hospital, Hunter New England Local Health District, Newcastle, NSW, Australia; 4The Australian Medical Council, Canberra, ACT, Australia

Correspondence: Mulavana S Parvathy Email [email protected]

Introduction: Australia depends on international medical graduates (IMGs) to meet workforce shortages. The current standard assessment for IMGs is by clinical examination in observed structured clinical encounter (OSCE) format lasting 200 minutes. There are concerns about adequateness of this assessment as it does not test the qualities required to practice in a new country. We introduced a programmatic performance-based assessment for IMGs to prepare them to meet these challenges. The workplace-based assessment (WBA) program involves six-month longitudinal programmatic assessments comprising of 12 mini-clinical evaluation exercises (Mini-CEX), five case-based discussions (CBD), two in-training assessments (ITAs) and two sets of multisource feedback (MSF) assessments. We assessed 254 IMGs since 2010. We conducted a survey to evaluate the satisfaction with the program and the outcomes of these doctors.

Methods: We surveyed 254 candidates from 2010 to 2020. The survey used “SelectSurvey” tool with 12 questions and free-text comments. All candidates were sent the survey link to their last registered mobile phone using “Telstra Instant Messaging Service”. We analysed the data using Microsoft “Excel”.

Results: We received 153 (60%) responses. Amongst them, 141 (92%) candidates did not require further supervised practice for general registration and 129 (84%) candidates hold general/specialist registration. The candidates found the program useful and felt well supported. They appreciated real patient encounters. The feedback with positive critiquing was helpful in improving their clinical practice. The negative themes were program costs and frustration with the length of the program.

Conclusion: Upon completion of the WBA program and obtaining the AMC certificate, most of the doctors were able to gain general registration. Seventy-eight (50%) candidates chose to continue their careers within the local area with 124 (80%) of them within the state. Our survey shows a comprehensive assessment program with immediate constructive feedback produces competent doctors to fill the medical workforce shortages.

Keywords: programmatic assessment, workplace based assessment, feedback, international medical graduates, foreign medical graduates

Introduction

Australia, like many other developed countries, depends on international medical graduates (IMGs) to meet workforce shortages. The proportion of doctors in the Australian medical workforce who obtained their initial qualification overseas increased by three per cent from 2013 to 2016.1 In 2016, statistics from the Medical Board of Australia indicated 32.2% of all the registered and employed medical workforce obtained their initial qualification overseas.1 IMGs are a key part of Australian medical workforce, most notably in rural areas.1 The above statistics indicate that 44.9% of the medical workforce working in outer regional areas and 43.1% in remote areas obtained their initial qualification overseas.1 This dependency is expected to continue for many more years.

The March 2012 Australian Federal Government report titled “Lost In The Labyrinth: Report on the inquiry into registration processes and support for overseas trained doctors” by the House of Representatives Standing Committee for Health and Ageing points to many issues that needed rectification.2 It made 45 recommendations including Workplace-Based Assessment (WBA), cross cultural orientation, and clinical supervision both before and after placement, especially for IMGs in regional, rural and remote areas.2 Medical migration, is an international issue and many of the recommendations are also generalizable to other countries.

The Australian Medical Council (AMC) provides several pathways for IMGs to obtain registration with the Medical Board of Australia/Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (MBA/AHPRA). The standard pathway of assessment for IMGs includes verification of qualifications as a doctor to practice medicine in their country of training, a MCQ delivered as a computer adaptive test followed by clinical skills assessment by an Observed Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) format or Workplace-Based Assessment (WBA).3,4 The OSCE assesses the candidates, using reliable and valid methods broadly accepted in medical education. However, an OSCE is only able to assess a candidate at moment-in-time. It is conducted over 200 minutes in a testing centre with 16 stations.3 Most of the stations use role players/actors with occasional real patients and some simulation equipment.

WBA is a novel method of programmatic assessments that provides an alternative pathway for IMGs working in the Australian healthcare system.5 The WBA program in Newcastle was developed in 2010 with the aim of addressing the problems associated with assessing and integrating IMGs into the Australian healthcare system.6 This is a proactive approach. It was developed in consultation with the AMC, the University of Newcastle and the Hunter New England Local Health District (HNELHD). WBA programs have high levels of validity because they are conducted in the workplace and are executed as part of normal clinical practice with real patients.7–10

From our literature search, this is the first programmatic assessment for IMGs anywhere in the world. The aim of this study was to evaluate the long-term outcome of the candidates, their satisfaction with the program and find out their professional trajectory.

Methods

The WBA Program in Newcastle is a six-month longitudinal programmatic assessment process focusing on clinical performance. The aim of this comparatively long assessment process is to provide assessors with multiple opportunities to assess the performance of IMGs.6 This in turn, provides the IMGs with the opportunity to improve their performance. The assessment includes 12 Mini-Clinical Evaluation Exercises (Mini-CEXs), five Case-based Discussions (CBDs), two In-training Assessments (ITAs) and two sets of 360-degree Multisource Feedback (MSF) assessments (one formative and one summative) (see Table 1). The disciplines covered are medicine, surgery, emergency, paediatrics, mental health and obstetrics and gynaecology.6 Candidates who pass this assessment program are eligible for AMC certification.4 Since its commencement in 2010, this program has assessed over 250 candidates in six hospitals within the Hunter New England Local Health District (HNELHD).11 The WBA Program is supported by the International Medical Graduate Unit (IMG Unit), which provides targeted IMG orientation, ongoing education, mentoring and linguistic support. Thus, the IMG Unit helps IMGs assimilate into the local medical workforce. A previous study assessing the composite reliability of WBA, found that it is a reliable assessment.12

|

Table 1 Tools and Criteria for Pass in WBA (Have to Pass All 4 Segments) |

The WBA team developed a survey using the “SelectSurvey” tool, with 12 questions and a section for free-text comments (see Table 2). This survey was piloted and then all the 254 candidates who completed the program were sent the survey link to their last registered mobile phone using “Telstra Instant Messaging Service” (TIMS). Follow-up reminder messages were sent every two weeks during the survey period. The survey was open for six weeks.

|

Table 2 Twelve Survey Questions |

The responses were collected and collated in Microsoft “Excel”. The data was analysed using the statistics tools (pivot table function) available within Microsoft “Excel”. As there was limited qualitative data, we did not undertake qualitative data analysis. However, we have included some of the free-text comments.

Results

Two hundred and fifty-four WBA candidates were surveyed during the time period of the audit. We received 153 (60%) responses.

Positive Themes

The candidates highlighted the following ‘positive themes’ a) acceptability of the program, “Best program, best people I am very thankful”, “Excellent program to help doctors and to help health workforce”; b) educational value and the immediate feedback “Great program, very educational” “I think the program was great with every mini CEX and case based discussion the examiner provided great feedback and I think that has helped me improve.”; c) enabled better integration into the Australian Health Care System and made it a learning experience “WBA program worked as an educational experience and helped with better integration into Australian health system” and d) appreciated real patient encounters rather than simulations. “It feels more realistic for me to talk to an actual patient than a pretend one”, “Very helpful programme for IMG, better assessment process than AMC clinical exam”. (See Table 1).

Negative Themes

The major ‘negative themes’ were, a) costs of the program and b) frustration with the length of the longitudinal assessment. (See Table 3 and Supplementary Table 3).

|

Table 3 Candidates Free-Text Feedback |

During the decade of implementation of the WBA Program, candidates from 32 countries were assessed. Of these, 35 (22.6%) had under one year of experience working in an Australian medical system, 80 (51.6%) had between 1–3 years’ experience, 40 (25.8%) had more than 3 years’ experience working under provisional registration. (See Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 for further details).

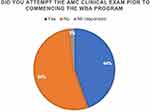

Sixty-nine (45%) candidates who did WBA had previously attempted the Australian Medical Council (AMC) clinical exam [Figure 1]. Of these, 59% of the candidates had attempted the clinical exam more than once [Figure 2].

|

Figure 1 Previous attempt at AMC clinical exam. |

|

Figure 2 Number of times AMC clinical exam was attempted. |

After completion of the WBA program, 141 (92%) of the candidates did not require supervised practice to apply for general registration. One hundred and twenty-nine candidates (84%) currently hold general and/or specialist registration with AHPRA and 134 (87%) candidates did not have any restrictions/conditions on their registration.

Currently, 15 (10%) candidates are practising as specialists and 40 (26%) are in a specialist training program. Thirty-eight (25%) are general practitioners and 22 (14%) are in general practice training program.

After completion of the WBA program, 78 (50%) of the candidates continue to work in the local health district and a further 46 (30%) are working within the state [Figure 3].

|

Figure 3 Current location of practice. |

Eighty-four (54%) of the candidates are working in a hospital setting, 46 (30%) are working in general practice and 12 (8%) are working in a hospital as well as general practice.

Discussion

This survey had a response rate of 60%. A sizeable number of the candidates who undertook WBA had previously attempted the AMC clinical exam. About 59% of them had multiple unsuccessful attempts at the AMC clinical exam. This seems to be consistent with a recent paper that showed that the pass rate in the AMC clinical exam was between 35% and 45% from 2010 to 2019.13 The AMC annual report in 2019 shows an AMC clinical examination pass rate of 27.1%.14 The pass rate of the HNELHD WBA program is 99%.

Given that six months of prior Australian medical workforce experience is a pre-requisite for enrolment in the program, most of the candidates did not require further supervised practice in order to be eligible for general/specialist registration. This is in contrast to the candidates who passed the AMC clinical examination, who are usually required to complete supervised practice before being eligible for general registration.3

Upon completion of the WBA program and acquisition of the AMC certificate, 90% of candidates were able to achieve general and/or specialist registration. The remaining 10% had limited registration and were in the process of completing their requirements for general/specialist registration as per the AHPRA regulations.

The survey indicates that 50% of the WBA candidates chose to continue their medical careers within the local area and a total 80% of the respondents are working in New South Wales. All the respondents are working either in a hospital setting or general practice providing medical care to the Australian community. Thus, these additional, well assessed and competent doctors are now filling the gaps in the health-care system in NSW.

A key principle of WBA is assessment of several domains by multiple different assessors with feedback requirement built into each assessment encounter.6,8 The qualitative comments indicated that this focused feedback with positive critiquing was found to be a crucial element that helped candidates improve their clinical and interpersonal skills. The candidates found the feedback to be relevant to working in the Australian medical workforce and helped them progress professionally. This has been consistent since the inception of the program in 2010.15

Limitations

A Workplace-based assessment program by its nature can only be offered to the doctors already employed in the Australian medical workforce. It requires an extensive administrative setup, multiple assessors in various disciplines to be calibrated/re-calibrated and be available to conduct these comprehensive assessments.6,7

The six-month program means a time commitment is required from the program coordinators, assessors and the candidates. Some other WBA programs in Australia extend up to or over 12 months.4,14 Most programs require six months of Australian medical experience prior to enrolment as well.4,6,14

The cost of the program was also thought to be one of its limitations. In a study in 2014, the actual cost (AUD $16,226) of the program outweighed the fees paid (AUD $6000) by the candidates.16 A large portion of this program works on the goodwill of the assessors. Currently, the HNELHD candidates pay $10,000 for a six-month program. The program is supported by the local health district, since it appreciates the benefit of well-trained and assessed IMGs to practice in the same local health district or within the region. The local health district recognises this to be a long-term investment for the welfare of the community.

The limitation of the survey was the inability to contact all the candidates. Some candidates had changed their contact information. The email addresses or mobile numbers of some others were not up to date. There were no in-depth interviews built in, and the researchers did not have the opportunity to further question the respondents.

Conclusion

The WBA program was found to be valid, reliable and acceptable to the learner from our previous work and this current evaluation. The nature of the program made it an educational experience as an “assessment for learning” as opposed to “assessment of learning”. Our literature review found this to be consistent with the experience in other countries/healthcare settings.14–16 Our survey shows that having such an assessment program produces competent doctors. The feedback from this survey and the success of the candidates indicate programmatic assessment is an authenticated way of IMG assessment, this will prepare them for the workplace for the next several decades to provide better health care for the population.

Ethics

Ethics approval for collecting and analysing the data was obtained from the Hunter New England Health Human Research Ethics Committee in 2010 (reference, AU201607-03 AU). All candidates provided consent for analysing their de-identified data.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to all the participants who gave their valued responses.

The Figures 1–3 were created by the authors using Microsoft Excel.

Funding

No funding to report.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Australian Government Department of Health. Medical workforce 2016 factsheet. Available from: https://hwd.health.gov.au/webapi/customer/documents/factsheets/2016/Medical%20workforce%20factsheet%202016.pdf.

2. Lost in the Labyrinth: report on the inquiry into registration processes and support for overseas trained doctors. Available from: http://www.cpmec.org.au/files/http___woparedaphgovau_house_committee_haa_overseasdoctors_report_combined_full_report1.pdf.

3. Australian Medical Council. Standard pathway. Available from: https://www.amc.org.au/assessment/pathways/standard-pathway/.

4. Australian Medical Council. Workplace based assessment (Standard Pathway). Available from: https://www.amc.org.au/assessment/pathways/standard-pathway/workplace-based-assessment-standard-pathway/.

5. Norcini J, Burch V. Workplace-based assessment as an educational tool: AMEE Guide No. 31. Med Teach. 2007;29:855–871. doi:10.1080/01421590701775453

6. Nair Balakrishnan BR, Hensley MJ, Parvathy Mulavana S, et al. A systematic approach to workplace-based assessment for international medical graduates. Med J Aust. 2012;196:399–402. doi:10.5694/mja11.10709

7. Singer A. The potential of workplace-based assessment of international medical graduates. Med J Aust. 2016;205:209–210. doi:10.5694/mja16.00794

8. Barrett A, Galvin R, Steinert Y, et al. A BEME (Best Evidence in Medical Education) review of the use of workplace-based assessment in identifying and remediating underperformance among postgraduate medical trainees: BEME Guide No. 43. Med Teach. 2016;38(12):1188–1198. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2016.1215413

9. Miller A, Archer J. Impact of workplace-based assessment on doctors’ education and performance: a systematic review. BMJ. 2010;341:c5064–c5064. doi:10.1136/bmj.c5064

10. Mortaz Hejri S, Jalili M, Masoomi R, et al. The utility of mini-clinical evaluation exercise in undergraduate and postgraduate medical education: a BEME review: BEME Guide No. 59. Med Teach. 2020;42(2):125–142. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2019.1652732

11. Nair BK, Moonen‐van Loon JM, Parvathy M, et al. Composite reliability of workplace based assessment of international medical graduates. Med J Aust. 2017;207(10):453. doi:10.5694/mja17.00130

12. Nair BR, Moonen-van Loon JMW, Parvathy MS, et al. Composite reliability of workplace-based assessment for international medical graduates. Med J Aust. 2016;205:212–216. doi:10.5694/mja16.00069

13. Yeomans ND, Sewell JR, Pigou P. Demographics and performance of candidates in the examinations of the Australian Medical Council, 1978–2019. Med J Aust. 2020;214:54–58. doi:10.5694/mja2.50800

14. Australian Medical Council limited. Annual report 2019. Available from: https://annual-report.amc.org.au/assessment-and-innovation/clinical-examinations/index.html.

15. Nair B, Parvathy M, Wilson A, et al. Workplace-based assessment; learner and assessor perspectives. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2015;6:317–321. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S79968

16. R nair BK, Searles AM, Ling RI, et al. Workplace-based assessment for international medical graduates: at what cost? Med J Aust. 2014;200(1):41–44. doi:10.5694/mja13.10849

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.