Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

Exploring the Mechanisms of Well-Being Occurrence Among Event Tourists: Mixed Empirical Evidence from Positive Psychology

Authors Zhang J, Li F , Xiang K

Received 11 April 2023

Accepted for publication 22 June 2023

Published 12 July 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 2581—2597

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S413012

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Mei-Chun Cheung

Jiankang Zhang,1 Fuda Li,2 Keheng Xiang1

1Zhejiang International Studies University, Hangzhou, People’s Republic of China; 2Hunan Normal University, Changsha, Hunan, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Jiankang Zhang; Keheng Xiang, Email [email protected]; [email protected]

Introduction: This study explores the well-being dimensional components of event tourists and their identification processes in validating the well-being occurrence mechanism of event tourism and the correlation between the well-being of event tourists and the frequency and length of event tourism.

Methods: This study adopted a sequential mixed-methods design that followed a pragmatic paradigm through a photo interview with event tourists and festival travel organizers (N=16). The qualitative research method provided evidence to explore the framework of content and dimensional identification of event tourists’ well-being according to Seligman’s PERMA model. The quantitative research phase (N=475) focused on identifying and validating the PERMA model in the event tourist well-being dimension through descriptive statistical analysis and validated factor analysis, followed by a one-way analysis of covariance to explore the effects of the frequency and endurance of FSE tourism.

Results: The results show quantitative differences in the well-being dimensions and framework presentation of the PERMA model (Positive emotion, Engagement, Relationship, Meaning, and Achievement). R (relationship) and A (achievement) are identified and validated as dimensions of well-being outcomes for event tourists, while single-day or short trips of 2– 3 days were most significant for event tourists’ perceived well-being.

Conclusion: This study provides an empirical argument, thus providing an empirical argument for uncovering the deeper influencing and exhibiting factors of the PERMA theoretical framework and a research paradigm for PERMA theory in more tourism behaviors and psychology. Second, this study provides an in-depth explanation of the five dimensions of well-being in the PERMA model. The findings show the salience of the relationship and achievement in FSE tourism well-being, providing theoretical insight into existing studies integrating positive psychology models for in-depth tourism well-being research.

Keywords: well-being, event tourists, mixed method, positive psychology, event tourism

Introduction

Academic attempts to explore the field of the festival and special events have existed for a long time, but a discipline of “studies of festivals and special events” began in the early 21st century, when social, cultural, environmental, and economic phenomena related to planned festivals were discussed, and the theoretical and academic institutional foundations of the field were established.1 Current research on the association between events and tourism shows that despite originating from different fields, they share a changing theme with a similar pattern.2 Existing research paradigms on Festival and Special Event (FSE) tourism include an interorganizational relationship approach3 using stakeholder theory to describe related FSE organizations or individuals;1 however, more studies are still based on descriptive cases.4 Event tourism, as a subsequent FSE concept, has been widely recognized,5 and event tourists have received academic attention. Gibson and Gibson6,7 identified active and passive event tourists, and Robinson and Gammon7–9 explored primary and secondary motivations for sports event tourism. Despite the continued focus on FSE and tourists, the existing research lacks theoretical rigor from a more established research field.4 Event tourism-related research is biased toward serving as a key marketing proposition for promoting places (Gatz and Page, 2016). Consequently, research related to the psychology, behavior, and value perceptions of event tourists has not yet been conducted at the micro level. Regarding research methodology, existing event tourism research lacks the interpretation and deepening of mixed research methods, which may provide greater flexibility for engaging in interdisciplinary research.4

Based on existing research, there is an urgent need for event tourism research to conduct deeper research on the micro psychology perspective of event tourists and using mixed research methods should be considered. Researchers have begun to use theories from positive psychology, such as happiness and well-being, as a lens to examine events in terms of their potential contributions to a good life and a life worth living.8 Several researchers have adopted the summative model of PERMA to conceptualize well-being.9,10 Thus, conceptualizing the well-being of event tourists and interpreting the hedonic form of well-being as a subjective feeling, including the positive emotional state of the individual,11 was a novel addition to the argument of FSE tourism for different types of participants. This study examined the mechanisms of well-being occurrence and well-being dimension identification of event tourists through a mixed study based on positive psychology, starting from the four common elements of well-being: growth, authenticity, meaning, and excellence.12

Therefore, to explore the mechanisms underlying the well-being of event tourists and the associated influencing factors, three key research questions were raised. First, from a positive psychology perspective, how will the PERMA dimensions of the tourism well-being of event tourists take effect? Second, how are the well-being framework dimensions of PERMA identified in the mechanisms of the tourism well-being of event tourists? Third, how does the well-being of event tourists relate to the frequency and duration of FSE tourism? This study combined qualitative and quantitative analyses using photo interviews to construct a well-being dimension identification and intrinsic framework for event tourists, guided by Seligman’s13 PERMA well-being framework. This study provides a research context for applying and deepening the theory of positive psychology in events and FSE tourism. In the context of the growing interest in FSE events, especially in the hosting of major sports events such as the Beijing Winter Olympics and the Hangzhou Asian Games in China, this study provides a positive psychological perspective on the well-being research and micro-psychological behavior of event tourists centered on large events, as well as empirical evidence for the mechanism and intrinsic interrelation of well-being in FSE tourism.

Literature Review

Progress and Review of FSE Tourism Research

While academic attempts to explore FSE tourism have existed for a long time, the recognition of “festival tourism” as a distinct form of tourism began in the early 21st century. Social, cultural, environmental, and economic factors related to planned festivals were explored by which theoretical structure was gradually established.1 FSE tourism has been conceptualized as encompassing all planned festivals and as an integrally developed marketing model. However, it is not usually considered a separate area of specialization. In most cases, FSE tourism is seen as an application or specialty of national tourism boards and destination marketing and management organizations.1 Events related to FSE tourism, such as cultural celebrations, festivals, carnivals, religious events, and arts and entertainment, are often categorized in the literature on cultural tourism14 The most frequently investigated aspect of FSE tourism is its economic and financial impact, and many existing studies have focused on the organizational aspects of FSE tourism. For example, a review by Formica15 found that 62 of 83 studies were related to organizational factors such as impact assessment, marketing, event profile, sponsorship, management, and trend forecasting.

There are three main streams of research on event tourism: the intrinsic mechanism between FSE tourism and individuals, the factors influencing supply and demand, and segmentation studies on festival tourism. In the first stream, festivals create opportunities for production and consumption by connecting experiences with tourists and residents, thereby setting expectations for individual experiences.16 Lee et al17 confirmed through empirical research that satisfied tourists develop a moderate emotional attachment to the host place and eventually become loyal visitors to the destination. Events provide not only material outcomes such as money but also intangible benefits stemming from positive tourist experiences, explaining the popularity of investigating individual experiences and perceptions.1 An increasing number of countries have hosted grand FSE tourism to attain legitimacy and prestige, attract tourist attention to their achievements, and promote trade and tourism.1

Regarding the second stream, studies have shown that hosting an event has a positive effect on the image of the host location. Most cities that have hosted major festivals have unique opportunities for transformation and revitalization. With the globalization of tourism and business, technological developments and increased revenues brought to tourism by distribution mechanisms have intensified competition among FSE tourism destinations and companies that provide FSE tourism products.18 Thus, FSE tourism destinations are challenged to offer attractive and memorable tourism experiences.19

In the third stream, an increasing number of studies have investigated the role of sporting event networks.20,21 Sports event tourism is recognized globally as a segment of FSE tourism.5 While the audience for sports events comprises tourists and residents of the host city, residents’ positive perceptions impact the quality of services and products.22 Visitor satisfaction is considered the primary accomplishment of event tourism, which motivates visitors to participate in similar events within the same destination and increases their intention to recommend the city to others as a tourist destination.23 Chen24 reviewed the behaviors, experiences, and values of sport event fans and concluded that personal values and “identity” explain why they are highly committed to the team, while Funk25,26 used the concept of self as a component of the “psychological continuum model” and found that awareness, attraction, attachment, and loyalty were progressive steps in hosting sport event visitors.

In summary, existing studies explore the organizational network, destination management, and marketing of FSE tourism according to three research approaches; however, most researchers explore organizational behavior from a macro perspective, and the exploration of tourists’ micropsychology remains relatively limited. In fact, theories from positive psychology, such as happiness and well-being, have been applied to examine FSE tourism.8 Research on event tourists’ well-being may expand the experiential meaning and value transformation of FSE tourism for tourism destinations.

Positive Psychology and Well-Being

Positive psychology is “the study of the conditions and processes that help people, groups, and institutions to flourish or function optimally”.27 It aims to “begin to catalyze a change in the focus of psychology from the previous focus on fixing the worst things in life to now building positive qualities”,13 Huta and Waterman12 suggested four common elements of well-being: growth, authenticity, meaning, and excellence.

There was no universally acknowledged definition of well-being in the literature,28 as “The understanding of the concept of well-being varies from discipline to discipline”.29 Pearce30 was among the first to acknowledge the positive psychology movement. Filep31 offered positive psychology in an explanation with relevant theoretical constructs (positive emotions, engagement, and meaning) that could better explain the relationship between positive psychology and tourism and provide a basis for explaining tourists’ well-being. In terms of conceptualizing the dimensions of well-being from a positive psychology perspective, the dominant taxonomy is realization and hedonism.12,32 This classification can be assessed at global, experiential, and motivational levels.29 The hedonism of well-being refers to “the reflection of virtue, excellence, the individual’s inner best, and the full development of the individual’s potential”,12 and focuses on “understanding happiness as a feeling of pleasure, enjoyment, and as a subjective emotional state” (Huta and waterman, 2014, p.1427). Thus, the conceptualization of well-being progresses into self-actualization in the state of “striving for excellence based on one’s unique potential”33 and what is primarily defined as three elements: pleasure, enjoyment, and life satisfaction.12 A follow-up study showed that realization had a lesser effect and lagged impact on well-being in the tourism experience than hedonism. Emotion and meaning represented the well-being of both hedonistic and self-actualized tourists.34

Based on the above discussion, the existing research and classification of the intrinsic association between positive psychology and well-being have been relatively clear, but the well-being specific to event tourists has not received much attention as a research subject; thus, our study aimed to investigate the well-being of event tourists from a positive psychology perspective. A review of the existing conceptual framework of well-being provides an adequate research context and basis for arguments regarding event tourists’ well-being.

Conceptual Framework of the Tourist Well-Being

Emotion and meaning represent the well-being of hedonic and growth-oriented visitors34 Positive emotions represent a fully hedonic dimension, whereas the remaining emotions are partially hedonic dimensions.35 Filep35 argued that the conceptualization of tourist well-being is complex. The hedonistic and growthist models currently accepted for summarizing the dimensions of the tourism experience seem to overlap. To explore the conceptual framework of tourism well-being, researchers have conceptualized well-being through summative models, the most classic of which are PERMA13 and DRAMMA (Detachment-Recovery, Autonomy, Mastery, Meaning, and Affiliation).36 Despite being a generic lifestyle model not originally designed for tourism research, PERMA remains popular in conceptualizing tourist well-being.9 Seligman13 first proposed the PERMA model, which incorporates hedonistic and happiness perspectives, with P representing positive emotions and an obvious hedonic element, including pleasure, ecstasy, intoxication, warmth, and comfort.

The PERMA model has been widely applied to tourism and entertainment research. Saunders et al37 conducted qualitative research to explore transformations in the daily lives of those who took long walks in natural environments, thus reinterpreting and connecting qualitative evidence with the five elements. The results of the use of PERMA in spectator sports,38 the development of specific mobile applications based on the model, and creative social media projects, will create opportunities for them to build closer connections and enhance positive emotions and connections to strengthen relationships and boost engagement with events. Huang et al39 identified consistency in applying PERMA to study the well-being of Chinese religious tourists. The results showed that their conceptualization of well-being was consistent with the dimensions of PERMA. Zhou et al40 explored how lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) activities affected the hedonic well-being of LGBT participants under the PERMA framework. However, a limitation of PERMA is its sensitivity to gender and social class, as these two factors can strongly influence people’s overall life experiences and how they make sense of different activities, places, and social interactions.41

Another widely accepted DRAMMA model by Newman et al36 proposes five dimensions of well-being for leisure experiences (including those of tourism). Detachment-recovery (DR) is a hedonic sense of separation from work and relaxation. As with PERMA, the remaining pillars of well-being are partially hedonic. Autonomy (A) is a feeling of willingness to engage in an activity, mastery (M) is about honing one’s skills to achieve success, meaning (M) is a sense of purpose, and affiliation (A), as in PERMA, is defined as social connection. In comparison, an overlap of dimensions was observed between PERMA and DRAMMA. The R (relationship) dimension in PERMA is similar to the last A (affiliation) in DRAMMA, M (meaning) in PERMA is similar to M (significance) in DRAMMA, and Achievement (A) in PERMA seems to include mastery (M) from DRAMMA.36 The only mechanism in DRAMMA that did not appear to have a precise counterpart in PERMA was disengagement recovery, although both may arguably play a role in generating positive emotions, engaging in leisure activities, or achieving PERMA.42

More recently, Filep et al43 integrated the different dimensions of PERMA and DRAMMA to include social connections as part of affiliation (A), which covers the experience of the basic human emotions of love, kindness, and friendship, thus emphasizing the social nature of most tourism experiences.44 In addition, the natural environment dimension is included as another part of affiliation (A) on the basis that connection to nature is positively associated with higher hedonism and higher well-being.45 The innovation of DREAMA is to expand the conceptualization of tourism well-being beyond human contact. DREAMA recognized that the relationship with the natural environment is as important as tourists’ psychological well-being, clarifying the core elements of visitor psychological well-being.43

In summary, the dimensions of the PERMA model, as a classical conceptualization of the three relevant models, provide a theoretical framework for our study of tourist well-being. Based on the qualitative aspects of the PERMA model, this study identifies whether the dimensions can be quantitatively verified by combining the DRAMMA and DREAMA models for dimensional-level theoretical inquiries to provide a theoretical framework. We are convinced that this theoretical inquiry will reveal the intrinsic mechanisms of event tourists’ well-being and provide a human-centered practical orientation and reference for the intelligent operation of large-scale sports events in the context of rapid technological development.

Based on this, this study reviewed past event tourism research and found a disconnect between the rapid growth of the event and festival-related industries and the progress and depth of existing research. The fragmented nature of existing research poses a challenge to researchers who consistently try to identify existing knowledge and research gaps.46 Although existing event-related research has addressed some theoretical perspectives, it has more often taken a business orientation, focusing on topics such as management and marketing,47 with little attention to the psychological mechanisms in tourists’ well-being, echoing Getz and Page’s48 suggestion that there is a need to better understand event regrouping with different groups (eg tourists and residents). Therefore, this study argues in the literature review section for advancing research on event tourists, FSE tourism, and integration with positive psychology and frameworks to bridge the research gap in existing event-related research on tourists’ micro psychology and behavior.

Methods

Design

This study used an exploratory qualitative approach combined with a quantitative approach to identify the mechanisms of well-being among FSE tourists. Through a photo interview method with event tourists and festival travel organizers (N=16), the qualitative research method provided qualitative evidence to explore the framework of the content and dimensional identification of event tourists’ well-being according to Seligman’s13 PERMA model. The quantitative research phase (N=475) focused on identifying and validating the PERMA model in the event tourist well-being dimension through descriptive statistical analysis and validated factor analysis, followed by one-way analysis of covariance to explore the effects of the frequency and endurance of FSE tourism. To ensure reliability and validity, this study simultaneously adopted research data triangulation of mutual evidence, constant comparison, and reflection through reviews and travelogues on travel social content portals and informed interviewees that all interview materials and representative photos were for scientific and academic purposes only, ensuring that interviewees’ personal and private information would not be disclosed to third parties.

This study adopted a sequential mixed-methods design that followed a pragmatic paradigm in which mixed methods provided a comprehensive and in-depth assessment of the research questions and increased the accuracy of the findings through a combination of exploratory and confirmatory analyses. A mixed-methods design enables researchers to address different research questions and use different development tools.49 A mixed-methods design is ideal for this study because it allows for a better resolution of interpretive research questions and draws valuable insights from existing theoretical and practical perspectives.50 The mixed methods approach used in this study was divided into three phases. The first phase was a qualitative study that explored the dimensions of event tourists’ well-being using the conceptual framework of well-being under positive psychology. The second phase was an in-depth study of the first phase to validate the dimensions of event tourists’ well-being framework in the occurrence mechanism of tourism well-being. The third phase was a further study to explore the relationship between the well-being of event tourists and the frequency and duration of FSE tourism.

Photo Interview and Data Collection

Collier51 first proposed the photo-elicitation method, in which photos helped capture the memory of the interviewee and improved the clarity of the conversation by providing visual cues. Accurate and rich data can be obtained by applying this method, which not only bridges cultural differences between informants and researchers52 but also balances the power asymmetries between them.53 Representative photographs can convey multiple levels of meaning,54 and researchers can use narratives inspired by photographs as a key data source.55 Photo interviews can further enhance the validity of interviews based on interviewees’ mindsets, experiences, and stories that can be fully shared and elaborated with the support of visual clues. Understanding the meanings associated with photographs can help researchers reconstruct travel experiences. The criticality of using photo interviews lies in the use of photographs provided by the participant, which are taken by the participant with instructions provided by the researcher56 and are, therefore, somewhat subjective, requiring the researcher to continually reflect on the implicit content of the photographs during the photo interviews.

The data collection for this study was divided into two phases, the first phase was from August 2022 to September 2022, in which eight interviewees who had more than three event trips in one year and eight event trip organizers were invited to conduct photo interviews, combined with the five dimensions of well-being proposed by Seligman13 and interviewees were invited to provide representative photos containing the PERMA dimensions. Each interviewee was required to collect 5–8 photos for the photo elicitation method. In the second phase (September–October 2022), the context and story behind each photo were presented. Each dimension was measured on a 7-point Likert scale and information such as the interviewees’ travel insurance, travel frequency, travel patterns, and demographic statistics. Before respondents began participating in the anonymous questionnaire, all respondents signed an informed consent form to ensure that their personal privacy would not be compromised. A total of 325 questionnaires were collected through the online questionnaire system, excluding samples that took less than 20 seconds to fill in, multiple-choice, wrong-choice, etc. Finally, 299 questionnaires were entered into the data analysis stage (92% retrieval rate).

Data Analysis

In this study, 158 photos were received during the qualitative research phase—9 photos per person—and 56 were entered into the representative photo analysis phase. There are no rules regarding sample size in qualitative research. Optimal sample size depends on various factors, including data saturation, accessibility of the target sample, and available time and resources.

The researcher repeatedly read the interview transcripts of the interviewees to become familiar with the content and obtain the data structure and framework during the reading process to make sense of the data and to describe, interpret, and summarize the data results.57 The qualitative coding in this study followed the five elements of problem solving proposed by Yussen and Ozcan58—role, situation, problem, action, and outcome—configured as contributors to the advancement of the storyline to form a representative photo-narrative structure map as a means of identifying the dimensions of the well-being of event tourists. Figure 1 shows an example of the coding results of the representative photo narrative structure maps of the two interviewees. In Figure 1, R1, as a representative of FSE travelers, narrates through representative photos the impact of career on event tourism and how to find individual value through event tourism, while Z4, as an FSE tourism organizer and practitioner, narrates through representative photos how to find a sense of control by breaking through the bottleneck of work.

|

Figure 1 Interviewees’ representative story narrative structure diagram (R1, Z4). |

Measurement

To identify the role of PERMA’s five dimensions of well-being among event tourists, this study referred to a 15-item scale of good validity and reliability measuring well-being,59 which validated the research context of snow sports tourists.59 Mirehie and Gibson60 also applied this scale to identify the PERMA dimensions of tourism well-being among female ski tourists. In this study, a change in the presentation of the questionnaire scale was made in conjunction with the research context of festival tourism, adopting a 7-point Likert scale, with 1 representing least likely and 7 representing most likely. The study also investigated factors influencing the well-being of festival tourism, such as the type of peers for festival tourism, the type of accommodation chosen for festival tourism, and the duration, frequency, and destination of FSE tourism participation. Demographic statistics, including the interviewees’ age, marital status, education level, and annual household income, were also considered. In this study, the questionnaire was pretested to reduce measurement and response errors, and 120 copies were placed among interviewees with festival travel experience. The measurement options of the questionnaire were modified and optimized, and the final version was placed as follows.

Results

Qualitative Research Findings: Dimensions of PERMA’s Framework

Dimension 1: Positive Emotions

Positive emotions can increase spiritual potential61 and contribute to an enhanced sense of meaningfulness in life.62 Interviewees’ expressions of positive emotions through the angle and content of their photos were shown in the representative photos, while the three positive emotions of interest, belief, and love were reflected in the representative photos and story structure diagrams of R1 and Z2. As shown in the interview with R1 in Appendix A, R1 was a freelancer and an avid follower of event tourism. As a freelancer, she often felt stress and anxiety about life. Still, her constant interest in event tourism provided her with positive emotions, strengthening her beliefs and allowing positive emotions to advance her immersion and integration into event tourism. Her love of her job kept her motivated to overcome life’s difficulties.

Z2’s expression of positive emotions as an FSE tourism organizer originated from the industry and his own work experience.

I have been working in festival organization and planning for the fifth year. I have kept my energy and spirit high because this job involved dealing with randomly changing situations that need to be grasped by ability and experience. I remember there was a time when our business was not possible due to COVID-19 measures, but we provided new ideas in designing the pre-sale type of FSE tourism products and believe that with positive emotions and moods, we can feel the joy of work and the happiness of life. (Z2)

In summary, this study compared the narrative storytelling of positive emotions by event tourists and festival organizers and found that the dimensions of positive emotions for event tourists were interest, belief, and love, whereas the dimensions of positive emotions for festival organizers were emotion, vitality, and spirit.

Dimension 2: Engagement

Engagement is another important dimension of PERMA. Seligman13 argued that people’s investment in valuable activities contributes to their life satisfaction and well-being. In this dimension of well-being, FSE tourists and festival organizers have different dimensions of engagement, as shown in Appendix A. R5, as a participant and tourist in the G20 Summit in Hangzhou, was full of spirit and pride and developed a sense of immersion in the experience. This deep involvement allowed her to perceive a sense of “flow”. As described in R5, during the reception and participation in the G20 Summit in Hangzhou, the interviewee sometimes felt alone in the world, and this “flow” of energy made them more proactive and involved in deeper participation. (R5)

Z3’s interviewees served as festival organizers and mentioned the interactivity and optimism of the participation dimension, as shown in Z3’s interview transcripts. We have been dealing with tourists who have many needs and our product supply is limited, but with healthy communication and interaction, we can feel the positive and optimistic spirit of loving this festival. (Z3)

In summary, event tourists and festival organizers have different emphases on the engagement dimension of well-being, with tourist interviewees favoring mainly the rituals of festival participation. In contrast, festival organizers favored the effectiveness of interaction with tourists.

Dimension 3: Relationships

Through the lens of positive psychology, people embrace, share, and spread positivity by building relationships that promote well-being. As shown in the representative picture of R3 interviewee in Appendix Q, he is an avid e-sports fan who attends and interacts with e-sports events at high frequencies, has an attachment to fellow attendees who attend events together and new strangers he meets on site, and is more proactive in creating social relationships with the same avid people so that such relationships sustain energy.

The importance of community and frequent interactions is also reflected in interviewee Z6’s interview transcript, which describes the value of building community relationships and frequent interactions with FSE tourism organizations from the perspective of festival organizers. We deal with visitors constantly; therefore, we constantly absorb their opinions to improve our festival products. We have many WeChat user groups where people build virtual social relationships and diversify their interactions. (Z6)

Thus, at the relational dimension level, event tourists and festival organizers have a common sense of well-being, construct physical and virtual relationships through different physical and emotional interactions, and derive positive emotional rewards from such relationships.

Dimension 4: Meaning

This is the first award our team received, for which we have put a lot of time, and at the end of every year, we evaluate our festival project. We are a team, and this constant awakening of our collective consciousness makes us realize the value of our profession’s existence. (Z2)

I learned about my interests and perceived my plans and goals by participating in festival tours. I will know what I want to do, how to do it, and how to develop in the future. I also know who I am, what I am doing, and what kind of person I want to become in the future. The festival tour brings me these perceptions so that I can face myself more clearly. (R4)

Thus, meaning (purpose) carries a strong value base that motivates one’s goal achievement.63 In the dimensional construct of meaning, the perceived direction of the well-being of event tourists and tourism organizers is egoistic and altruistic, respectively, with the former rationalizing and realizing the meaning of goals through individual perceptions and the latter enhancing the meaning of work well-being through team cohesion and collective consciousness.

Dimension 5: Achievement

Achievement is the outcome dimension of the PERMA framework and can be functional, hedonic, or social.64 Individual and organizational achievements were found in both types of interviewees in this study, as shown in the representative picture and interview data provided by interviewees in Appendix A for Z4 and in the interview transcripts for interviewees in R2.

I have been promoted in a festival-planning company, with my picture on the company logo wall: I feel my sense of achievement and self-efficacy; I have a closer relationship with this company; I grow with the company; I would like to work in this company for another ten years; I am very happy here because I have a particular achievement at each stage, which brings me constant recognition in the industry. (Z4)

I feel calm after each event, even when surrounded by noise because I know that I love the event more. I follow the event and cover a lot of news, and my sense of accomplishment is indescribable, allowing me to connect my identity as a festival traveler with that of a working journalist, where the happiness of life and work can be oriented towards the results of my contribution. (R2)

Thus, two dimensions of achievement are consistently found, where event tourists carry multiple identities and focus on the achievements that come with life and work: peace of mind, recognition, and commitment, while professional commitment, organizational commitment and industry recognition become the segmentation directions of the achievement dimensions for festival organizers.

PERMA Model of Event Tourists’ Well-Being

Based on the above findings on PERMA dimensions in qualitative research, this study formed a PERMA model for FSE tourism based on the five elements of the original framework, as shown in Figure 2. Event tourists and festival organizers generated different well-being outcomes due to differences in their roles and participation, with the larger difference being M (significance) for the two different group samples of the well-being dimension. In terms of constructing the well-being dimension, the tourism well-being of event tourists is egoistic. In contrast, the well-being of FSE tourism organizers is altruistic, which reflects the variability in the perception and dimensional interpretation of the well-being of the respondent group sample.

|

Figure 2 PERMA framework for the content of well-being interactions between FSE visitors and FSE organizers. |

This study uses a photo-elicitation qualitative interviewing method to trigger interviewee memory and improve the dynamics of the interviewee-researcher relationship with each other,65 generating unpredictable answers66 complementing the narrative to convey the meaning of the experience67 and reducing the power imbalance between the researcher and interviewees,53 as in the first phase of this study, where the interviewees provided representative photographs and interpreted and described them to explore the metaphors behind them, enabling a multidimensional interpretation and analysis of the interviewees’ tourism well-being from multiple research perspectives, diverse data, etc., allowing the interviewees and the researcher to be on a platform that facilitates contextual clues to the dialogue.68

Quantitative Findings: Dimensional Identification of the PERMA Model

Descriptive Analysis

A total of 375 questionnaires (N=375) were obtained from online data collection, and 299 were entered into the data analysis (N=299) after removing the results of invalid questionnaires. Most interviewees were married (55%) and had a bachelor’s degree (72%). Regarding employment status, 70% worked full-time, 4% were freelancers, and the higher proportion of annual household income was less than 200,000 (37%) and 200,000 to 300,000 (33%). Therefore, the sample used in this study conformed to the characteristics of heterogeneity and was suitable for subsequent quantitative analyses. A descriptive statistical analysis of the interviewees is presented in Table 1. In Table 1, all respondents’ information is anonymized in order to ensure that the respondents’ private information is protected, ensuring that each respondent is aware that all subjects of the collected information are anonymous.

|

Table 1 Descriptive Statistical Analysis of Interviewees’ Information |

Identification and Validation of PERMA’s Well-Being Framework Dimensions Among Event Tourists

The study first conducted a reliability test on the 15 options of the five dimensions of the PERMA scale. The test results showed that Cronbach’s alpha was 0.875, in the range of 0.80–0.90, and the questionnaire had good reliability. Next, this study conducted a CFA analysis on the five dimensions of PERMA, as shown in Table 2. To examine the differential validity of the five variables PP, EE, RR, MM, and AA, this study conducted a validation factor analysis using Mplus software. The results showed p<0.01, indicating significant relationships between the variables, χ2 = 163.169, df = 80, CFI = 0.936>0.9, TLI = 0.916>0.9, SRMR = 0.047< 0.5, RMSEA = 0.059<0.08, indicating that the model fit was good and well differentiated. In addition, the p-values from all five dimensions were less than 0.01, presenting high significance, but only R2, A2, and A3 of the indicators had factor loadings greater than 0.7. Therefore, the division of dimensions by PERMA was not ideal.

|

Table 2 CFA Analysis Results |

The Relationship Between the Frequency and Length of Travel and Event Tourists’ Well-Being

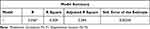

To explore the factors influencing the frequency and length of travel that affect the well-being of event tourists, this study used multivariate hierarchical regression analysis, where control variables such as age, education, annual income, and occupation were put into the model in the first step. The insignificant control variables age and education were removed in the second step, and then F1-F4 of the frequency of travel were put into the model, as summarized in Table 3.

|

Table 3 Model Summary Results |

The results of the ANOVA analysis are shown in Table 4. Significance of 0 < 0.05 indicated a statistically significant comparison between groups, so it can be concluded that there was a significant relationship between the frequency and length of tours and event tourists’ well-being. The effects of the frequency and length of tours on the well-being of event tourists are shown in Table 4.

|

Table 4 Results of ANOVA Analysis |

According to Table 5, F1 and F2 had a significant effect on the well-being of event tourists; that is, one-day trips and 2–3-day trips brought the most significant well-being perceptions and experiences of event tourists, while F3 and F4 had p-values greater than 0.1, that is, not significant, on the well-being of event tourists, which supports Mirehie and Gibson’s6 study of female ski travelers’ association between travel time and well-being.

|

Table 5 The Effect of Travel Length on the Well-Being of FSE Tourists |

Discussion

This study explored the dimensional presentation of the five dimensions of PERMA in event tourists and festival organizers using the positive psychological well-being model PERMA as a framework, measured the PERMA framework in event tourists’ well-being through scales, and explored the significance of tour length on event tourists’ well-being.

The results showed that there were differences in the PERMA well-being dimensions and framework presentation between event tourists and festival organizers, with event tourists favoring self-interested individualism on well-being dimensions and festival organizers favoring altruistic collectivism on well-being components; among the quantitative findings, R (relationship) and A (achievement) were identified and validated as dimensions of well-being outcomes for event tourists, while short trips of one day or 2–3 days were most significant for event tourists’ well-being perceptions.

For the research question of the dimensions of tourism well-being, the findings of this study’s guiding model of the PERMA framework echoed Zhou et al’s40 findings for LGBT activities affecting the hedonic and well-being of LGBT participants and organizers, highlighting the variability of well-being subjects and validating that positive emotions are dynamic and variable and that PERMA’s altruistic achievements reflect organizers’ positive influence and way of helping others.40 In research question 1 regarding the A (achievement) dimension of well-being, this study is consistent with the findings of Laing and Frost,42 confirming the increase in the positive emotion dimension and the importance of identity as a support mechanism, highlighting that the professional identity of FSE tourism organizers can be extended to tourism behavior. Unlike previous studies, this study challenges the inadequacy of PERMA’s R (relationship) well-being dimension explored in previous studies, in which PERMA’s affiliation with the relationship was too narrowly understood as a relationship with other people.36 In contrast, this study found that the relational dimension of event tourists and organizers is an active, communal, and diverse interaction and that the nature of this interaction affects the psychological or sensory state of the individual, which affects well-being.69

For the research question of the mechanisms of occurrence of tourism well-being, the quantitative study revealed that of the five dimensions of PERMA, only the sub-options R (relationship) and A (achievement) were significant, similar to Fredrickson and Kurtz’s70 study, highlighting that individuals receive, share, and spread positivity by building relationships over time, thereby contributing to their well-being, and that the interactive nature at the core of relationship construction allows deep engagement to influence individuals’ mental and sensory states, thus shaping the impact pathways of well-being.69 In terms of the A (achievement) dimension, this study echoes the findings of Voss et al64 in deepening the categorization of achievement as functional, hedonic, and social, which indirectly reflects the explanatory arguments of altruism in achievement. Thus, the two dimensions of relationship and achievement were identified in quantitative research to highlight the mechanisms at play in generating well-being in event tourists who achieve gains in achievement through interactive relationship construction, thus reflecting the quest for success and mastery.13

For research questions on the frequency and duration of event tourism, excessive duration is detrimental to the well-being of event tourists due to the specific context of festival tourism. This finding differs from previous research on the potential cumulative effect of participation in ski tourism,19 where travel-generated well-being accumulates over time and frequency. However, this study confirms that excessive travel duration is not associated with increased well-being in FSE tourism contexts,60 which may be explained by travel stress and fatigue in tourism.71 Thus, the relationship between the well-being of event tourists, time, and frequency was revealed, providing a basis for subsequent research to explore other important influences on the well-being of event tourism.

The theoretical contributions of this study are three-fold. First, this study confirmed the diversity of the sample of the five dimensions of PERMA as a positive psychology framework and explored the variability of PERMA in the five dimensions of FSE tourists and FSE organizers through the photo citation talk method, thus providing an empirical argument for uncovering the deeper influencing and exhibiting factors of the PERMA theoretical framework and a research paradigm for PERMA theory in more tourism behaviors and psychology. Second, this study provided an in-depth explanation of the five dimensions of well-being in the PERMA model, and the findings show the salience of relationship and achievement in FSE tourism well-being, which provided theoretical insight into existing studies integrating positive psychology models for in-depth tourism well-being research. Newman et al36 highlight the R (relationship) dimension in PERMA through a rigorous assessment. Similar to the dimension of A (affiliation) in the DRAMMA model, A (achievement) corresponds to DRAMMA’s mastery (M); therefore, the parsing and judgment of the theoretical framework in this study provide a theoretical basis for the construction of the direction and subdivision indicators of the dimensions of tourism well-being. Third, this study adds physical and sensory subdimensions to the original PERMA framework, supporting Matteucci and Soncini’s72 finding that short periods of FSE tourism can generate physical stamina and mental energy regulation that can produce relatively significant perceptions of well-being, providing new arguments and directions for the physical dimension of future tourism well-being research dimensions.

This study contributes to the study of event tourists from a positive psychological perspective. While previous studies of event tourists have focused on marketing and business management perspectives, the present study uses the dimensions developed by the model of happiness conceptualized in positive psychology for event tourists to demonstrate that true well-being is more refined than psychological pleasure and enjoyment levels of meaning and fulfillment and more systematically reflect the quality of the individual experience.13 This study explored some specific well-being triggers, such as reconnection, gratitude, taste, and mindfulness.34 In addition, the broadened interpretation of the dimensions of the PERMA framework model reflects that tourism well-being can be enhanced by one’s inner self and sense of belonging to the social world to cope with the stresses of daily life,34 which gradually extends beyond the individual to society and manifests itself in positive attitudes towards social development issues73 and value co-creation with the participation of multiple subjects in FSE tourism.74 Ultimately, this study echoes the positive psychology research outlook proposed by Fliep31 an pathways to enhance tourists’ meaning and self-transformation through positive tourism experiences.

This study also makes a methodological contribution by adopting a mixed-methods design incorporating elements of both qualitative and quantitative methods (Tashakkori & Teddlie).75 Previous studies have been limited to the depth of exploration of the topic of event tourists, and the mixed-methods design of this study is therefore valuable for generating rich insights and informing theory and practice development.76 In this study, the findings of the well-being dimensions and framework based on the qualitative study of event tourists were validated by an in-depth analysis of the significance and relevant influences of the dimensions of the well-being framework through quantitative analysis, which achieved a “complementary” implementation of the research questions. Exploring different aspects of the same complex phenomenon provides a deeper understanding and interpretation of the research questions and permits “triangulating the evidence” through the corroboration of data.75,77

Practical Implications

The empirical contributions and research implications of this study, in terms of FSE tourism organization and planning, suggest that event organizers should approach the design and development of tourism products in terms of the well-being dimension of event tourists’ participation, giving full consideration to the time interval and duration of FSE tourism products and starting from the physical strength and energy of tourists so that tourists can the greatest well-being at the appropriate time. As for the excavation of the tourism well-being experience for event tourists, FSE tourism organizers pay attention to the physical and mental health issues of event tourists and provide the differences and highlights of well-being dimensions in the marketing copy design, which can match event tourists with different needs and adequately orient technology utilization to improve the well-being of event tourists.

For the government, in the process of developing event tourism planning and support policies, it is important to pay attention to the characteristics of the regional market and users to segment planning and marketing of the psychology and behavior of event tourists with the dimensions in the framework of positive psychology, to focus on the deep excavation of the well-being of event tourism product suppliers and event tourists in the policy, to improve well-being as the goal, and to enhance the well-being of multiple stakeholders. Thus, event tourism policy can be integrated and developed with other cultural tourism modules to jointly promote the strategic planning of regional event tourism and produce positive effects.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Studies

This study has research limitations in terms of sample size. Although it has ensured the heterogeneity of the sample, the quantitative limitations and quality of the sample need further refinement. Regarding research methodology, this study tapped into interviewees’ reports through the citation of representative photos and triangulated mutual evidence through a third-party content operation platform; however, the formation of evidence chains and the adequacy of arguments must be verified by further quantification. Future research can focus on other influencing factors and mechanisms that affect tourists’ well-being and explore the process of well-being changes in FSE tourism through experimental methods and longitudinal tracking studies to provide richer arguments and research paths for studying event tourists’ well-being.

Ethics Statement

We declare that the participants in our study allowed us to use their data for academic research and publications. All participants were anonymous, and their data were protected. All programs in our study were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Zhejiang International Studies University, and all participants obtained the privacy protection policy and process of this research.

Funding

The research was supported by the Philosophy and Social Science Planning Program of Zhejiang Province of China (No. 20NDJC159YB) for Deconstruction and Practice Orientation of Communication Technologies of “Intelligent Asian Games” By Professor Jiankang Zhang.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest for this work.

References

1. Getz D. Event tourism: definition, evolution, and research. Tourism Manag. 2008;29(3):403–428. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2007.07.017

2. Kim JD, Wang Y, Yasunori Y. The Genia event extraction shared task. In:

3. Stokes R. Relationships and networks for shaping events tourism: an Australian study. Event Manag. 2006;10(2):145–158. doi:10.3727/152599507780676652

4. Laing J. Festival and event tourism research: current and future perspectives. Tourism Manag Perspect. 2018;25:165–168. doi:10.1016/j.tmp.2017.11.024

5. Presenza A, Sheehan L. Planning tourism through sporting events. Int J Event Fest Manage. 2013;4(2):125–139. doi:10.1108/17582951311325890

6. Gibson HJ. Sport tourism: a critical analysis of research. Sport Manag Rev. 1998;1(1):45–76. doi:10.1016/S1441-3523(98)70099-3

7. Gibson EL. Emotional influences on food choice: sensory, physiological and psychological pathways. Physiol Behav. 2006;89(1):53–61. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.01.024

8. Filep S, Volic I, Lee IS. On positive psychology of events. Event Manag. 2015;19(4):495–507. doi:10.3727/152599515X14465748512687

9. Dillette A, Douglas A, Martin D. Do vacations really make us happier. Exploring the relationships between wellness tourism, happiness and quality of life. J Tourism Hospit. 2018;7(355):2167–2269. doi:10.4172/2167-0269.1000355

10. Pourfakhimi S, Duncan T, Coetzee WJL. Electronic word of mouth in tourism and hospitality consumer behaviour: state of the art. Tour Rev. 2020;75(4):637–661. doi:10.1108/TR-01-2019-0019

11. Haybron DM. Two philosophical problems in the study of happiness. J Happiness Stud. 2000;1(2):207–225. doi:10.1023/A:1010075527517

12. Huta V, Waterman AS. Eudaimonia and its distinction from hedonia: developing a classification and terminology for understanding conceptual and operational definitions. J Happiness Stud. 2014;15(6):1425–1456. doi:10.1007/s10902-013-9485-0

13. Seligman M. PERMA and the building blocks of well-being. J Posit Psychol. 2018;13(4):333–335. doi:10.1080/17439760.2018.1437466

14. McKercher B, Du Cros H. Cultural Tourism: The Partnership Between Tourism and Cultural Heritage Management. Routledge; 2002.

15. Formica S. The development of festivals and special events studies. Fest Manag Event Tour. 1998;5(3):131–137.

16. Snepenger D, Murphy L, Snepenger M, Anderson W. Normative meanings of experiences for a spectrum of tourism places. J Travel Res. 2004;43(2):108–117. doi:10.1177/0047287504268231

17. Lee J, Kyle G, Scott D. The mediating effect of place attachment on the relationship between festival satisfaction and loyalty to the festival hosting destination. J Travel Res. 2012;51(6):754–767. doi:10.1177/0047287512437859

18. Mariani M, Baggio R, Buhalis D, Longhi C. Tourism management, marketing, and development: volume I. In: The Importance of Networks and ICTs (Vol. 1). Springer; 2014.

19. Filo K, Coghlan A. Exploring the positive psychology domains of well-being activated through charity sport event experiences. Event Manag. 2016;20(2):181–199. doi:10.3727/152599516X14610017108701

20. Cobbs J, Hylton M. Facilitating sponsorship channels in the business model of motorsports. J Mark Channels. 2012;19(3):173–192. doi:10.1080/1046669X.2012.686860

21. Mackellar J, Nisbet S. Sport events and integrated destination development. Curr Issues Tourism. 2017;20(13):1320–1335. doi:10.1080/13683500.2014.959903

22. Wall G, Mathieson A. Tourism: Change, Impacts, and Opportunities. Pearson Education; 2006.

23. Shonk DJ, Chelladurai P. Service Quality, satisfaction, and intent to return in event sport tourism. J Sport Manag. 2008;22(5):587–602. doi:10.1123/jsm.22.5.587

24. Chen PJ. The attributes, consequences, and values associated with event sport tourists’ behavior: a means–end chain approach. Event Manag. 2006;10(1):1–22. doi:10.3727/152599506779364651

25. Funk D. Consumer Behaviour in Sport and Events: Marketing Action. Oxford: Elsevier; 2008.

26. Funk D. Consumer Behaviour in Sport and Events. Abingdon: Routledge; 2012.

27. Gable SL, Haidt J. What (and why) is positive psychology? Rev Gen Psychol. 2005;9(2):103–110. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.103

28. Dodge R, Daly AP, Huyton J, Sanders LD. The challenge of defining wellbeing. Int J Wellbeing. 2012;2(3):222–235. doi:10.5502/ijw.v2i3.4

29. Voigt C. Employing hedonia and eudaimonia to explore differences between three groups of wellness tourists on the experiential, the motivational and the global level. In: Filep S, Laing J, Csikszentmihalyi M, editors. Positive Tourism. London: Routledge; 2017:

30. Pearce PL. The relationship between positive psychology and tourist behavior studies. Tourism Anal. 2009;14(1):37–48. doi:10.3727/108354209788970153

31. Filep S. Positive psychology and tourism. In: Handbook of Tourism and Quality-of-Life Research. Dordrecht: Springer; 2012:31–50.

32. Ryan RM, Deci EL. On happiness and human potentials: a review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:141–166. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141

33. Ryff CD, Singer BH. Know thyself and become what you are: a eudaimonic approach to psychological well-being. J Happiness Stud. 2008;9(1):13–39. doi:10.1007/s10902-006-9019-0

34. Vada S, Prentice C, Scott N, Hsiao A. Positive psychology and tourist well-being: a systematic literature review. Tourism Manag Perspect. 2020;33:100631. doi:10.1016/j.tmp.2019.100631

35. Filep S. Moving beyond subjective well-being: a tourism critique. J Hosp Tourism Res. 2014;38(2):266–274. doi:10.1177/1096348012436609

36. Newman A, Ucbasaran D, Zhu FEI, Hirst G. Psychological capital: a review and synthesis. J Organiz Behav. 2014;35(S1):S120–S138. doi:10.1002/job.1916

37. Saunders R, Laing J, Weiler B. Personal transformation through long- distance walking. In: Filep S, Pearce P, editors. Tourist Experience and Fulfilment: Insights from Positive Psychology. United Kingdom: Routledge; 2014:127–146.

38. Doyle L, Brady AM, Byrne G. An overview of mixed methods research–revisited. J Res Nurs. 2016;21(8):623–635. doi:10.1177/1744987116674257

39. Huang K, Pearce PL, Wu MY, Wang XZ. Tourists and Buddhist heritage sites: an integrative analysis of visitors’ experience and happiness through positive psychology constructs. Tourist Stud. 2019;19(4):549–568. doi:10.1177/1468797619850107

40. Zhou PP, Wu MY, Filep S, Weber K. Exploring well-being outcomes at an iconic Chinese LGBT event: a PERMA model perspective. Tourism Manag Perspect. 2021;40:100905. doi:10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100905

41. Abbas G, Khalily MT, Riaz MN. Mediating role of work-related attitudes between leadership styles and well-being. Pak J Com Soc Sci. 2016;10(2):257–273.

42. Laing JH, Frost W. Journeys of wellbeing: women’s travel narratives of transformation and self-discovery in Italy. Tourism Manag. 2017;62:110–119. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2017.04.004

43. Filep S, King B, McKercher B. Reflecting on tourism and COVID-19 research. Tourism Recreat Res. 2022;1–5. doi:10.1080/02508281.2021.2023839

44. Singh SK, Pradhan RK, Panigrahy NP, Jena LK. Self-efficacy and workplace well-being: moderating role of sustainability practices. BIJ. 2019;26(6):1692–1708. doi:10.1108/BIJ-07-2018-0219

45. White MP, Alcock I, Wheeler BW, Depledge MH. Coastal proximity, health and well-being: results from a longitudinal panel survey. Health Place. 2013;23:97–103. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2013.05.006

46. Duffy M, Mair J. Future trajectories of festival research. Tourist Stud. 2021;21(1):9–23. doi:10.1177/1468797621992933

47. Park SB, Park K. Thematic trends in event management research. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag. 2017;29(3):848–861. doi:10.1108/IJCHM-09-2015-0521

48. Getz D, Page SJ. Progress and prospects for event tourism research. Tourism Manag. 2016;52:593–631. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2015.03.007

49. Bryman A. Telling technological tales. Organization. 2000;7(3):455–475. doi:10.1177/135050840073005

50. Bryman A, Brown S, Sullivan Y. Guidelines for conducting mixed-methods research: an extension and illustration. JAIS. 2016;17(7):435–494. doi:10.17705/1jais.00433

51. Collier JC. Photography in anthropology: a report on two experiments. Am Anthropol. 1957;59(5):843–859. doi:10.1525/aa.1957.59.5.02a00100

52. Collier J, Collier M. Visual Anthropology: Photography as a Research Method. UNM Press; 1986.

53. Packard J. ‘I’m gonna show you what it’s really like out here’: the power and limitation of participatory visual methods. Vis Stud. 2008;23(1):63–77. doi:10.1080/14725860801908544

54. Jokinen E, Veijola SEJ. Mountains and landscapes: towards embodied visualities. In: Visual Culture and Tourism. Berg Publishers; 2003:259–278.

55. Can D, Taylor C, Ricoeur P. Ricoeur on narrative. In: Ricoeur OP, editor. Discussion. Routledge; 2002:174–201.

56. Wagner WJ. Photography and the right to privacy: the French and American approaches. Cath Law. 1979;25:195.

57. Creswell JW, Tashakkori A. Editorial: differing perspectives on mixed methods research. J Mixed Methods Res. 2007;1(4):303–308. doi:10.1177/1558689807306132

58. Yussen SR, Ozcan NM. The development of knowledge about narratives. Issues Educ. 1997;2:1–68.

59. Butler J, Kern ML. The PERMA-Profiler: a brief multidimensional measure of flourishing. Intnl J Wellbeing. 2016;6(3):1–48. doi:10.5502/ijw.v6i3.526

60. Mirehie M, Gibson HJ. The relationship between female snow-sport tourists’ travel behaviors and well-being. Tourism Manag Perspect. 2020;33:100613. doi:10.1016/j.tmp.2019.100613

61. Smith BW, Ortiz JA, Wiggins KT, Bernard JF, Dalen J. Spirituality, resilience, and positive emotions. 2012.

62. King LA, Hicks JA, Krull JL, Del Gaiso AK. Positive affect and the experience of meaning in life. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2006;90(1):179–196. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.90.1.179

63. Shamir B. Meaning, self and motivation in organizations. Organ Stud. 1991;12(3):405–424. doi:10.1177/017084069101200304

64. Voss KE, Spangenberg ER, Grohmann B. Measuring the hedonic and utilitarian dimensions of consumer attitude. J Mark Res. 2003;40(3):310–320. doi:10.1509/jmkr.40.3.310.19238

65. Prosser J. Image-Based Research: A Sourcebook for Qualitative Researchers. Psychology Press; 1998.

66. Collier D, Cardoso FH. The New Authoritarianism in Latin America. Princeton University Press; 1979.

67. Weade R, Ernst G. Pictures of life in classrooms, and the search for metaphors to frame them. Theor Pract. 1990;29(2):133–140. doi:10.1080/00405849009543444

68. Folkestad H. Getting the picture: photo‐assisted conversations as interviews. Scand J Disabil Res. 2000;2(2):3–21. doi:10.1080/15017410009510757

69. Vittersø J. Handbook of Eudaimonic Well-Being. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2016:253–276.

70. Fredrickson BL, Kurtz LE. Cultivating positive emotions to enhance human flourishing. In: Applied Positive Psychology: Improving Everyday Life, Health, Schools, Work, and Society. Routledge; 2011:35–47.

71. Wicker P. The carbon footprint of active sport participants. Sport Manag Rev. 2019;22(4):513–526. doi:10.1016/j.smr.2018.07.001

72. Matteucci MC, Soncini A. Self-efficacy and psychological well-being in a sample of Italian university students with and without Specific Learning Disorder. Res Dev Disabil. 2021;110:103858. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2021.103858

73. Pearce PL. Tourists’ written reactions to poverty in Southern Africa. J Travel Res. 2012;51(2):154–165. doi:10.1177/0047287510396098

74. Lin Z, Chen Y, Filieri R. Resident-tourist value co-creation: the role of residents’ perceived tourism impacts and life satisfaction. Tourism Manag. 2017;61:436–442. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2017.02.013

75. Tashakkori A, Teddlie C. Integrating qualitative and quantitative approaches to research. SAGE Handbook Appl Soc Res Methods. 2009;2:283–317.

76. Shi S, Leung WKS, Munelli F. Gamification in OTA platforms: a mixed-methods research involving online shopping carnival. Tourism Manag. 2022;88:104426. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104426

77. Greene JC. Mixed Methods in Social Inquiry. Vol. 9. John Wiley & Sons; 2007.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.