Back to Journals » Advances in Medical Education and Practice » Volume 7

Emotional maturity of medical students impacting their adult learning skills in a newly established public medical school at the east coast of Malaysian Peninsula

Authors Bhagat V, Haque M , Bin Abu Bakar YI, Husain R, Khairi CM

Received 22 July 2016

Accepted for publication 2 September 2016

Published 14 October 2016 Volume 2016:7 Pages 575—584

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S117915

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Md Anwarul Azim Majumder

Video abstract presented by Yasrul Izad Bin Abu Bakar.

Views: 179

Vidya Bhagat,1 Mainul Haque,2 Yasrul Izad Bin Abu Bakar,3 Rohayah Husain,1 Che Mat Khairi1

1The Unit of Psychological Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin, Kuala Terengganu, Terengganu, Malaysia; 2The Unit of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine and Defense Health, National Defense University of Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; 3The Unit of Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin, Kuala Terengganu, Terengganu, Malaysia

Abstract: Emotional maturity (EM) is defined as the ability of an individual to respond to situations, control emotions, and behave in an adult manner when dealing with others. EM is associated with adult learning skill, which is an important aspect of professional development as stated in the principles of andragogy. These principles are basically a characteristic feature of adult learning, which is defined as “the entire range of formal, non-formal, and informal learning activities that are undertaken by adults after an initial education and training, which result in the acquisition of new knowledge and skills”. The purpose of this study is to find out the influence of EM on adult learning among Years I and II medical students of Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin (UniSZA). The study population included preclinical medical students of UniSZA from Years I and II of the academic session 2015/2016. The convenient sampling technique was used to select the sample. Data were collected using “EM scale” to evaluate emotional level and adult learning scale to assess the adult learning scores. Out of 120 questionnaires, only six response sheets were not complete and the remaining 114 (95%) were complete. Among the study participants, 23.7% (27) and 76.3% (87) were males and females, respectively. The data were then compiled and analyzed using SPSS Version 22. The Pearson’s correlation method was used to find the significance of their association. The results revealed a significant correlation between EM and adult learning scores (r=0.40, p<0.001). Thus, the study result supports the prediction, and based on the current findings, it can be concluded that there is a significant correlation between EM and adult learning and it has an effect on the students. Medical faculty members should give more emphasis on these aspects to produce health professionals. Henceforward, researchers can expect with optimism that the country will create more rational medical doctors.

Keywords: adult learning skill, emotional maturity, medical students, UniSZA, Malaysia

Introduction

Emotional intelligence (EI) and emotional maturity (EM)

EI is the skill to recognize and accomplish one’s personal emotions and the emotions of others.1 EI is also demarcated as an ability-based skill that permits for training in precise proficiencies that can be directly useful to a particular arena.2 Emotionally intelligent people have good emotional awareness, which includes social and personal intelligence. Therefore, they have the ability to connect emotions and to think to solve problems, in managing interpersonal relationships and interactions, especially in the business and educational spheres.1,3 Consequently, emotionally intelligent people possess professional personalities needed, especially, in medical education, to ensure proper health care of any community.4 Multiple studies have recommended that medical schools are interested in developing EI in their undergraduates to ensure better health care.5–8 EI of medical students paves the way to the transition of medical students from their pedagogy to andragogy learning.2,9 Lecturers who possess and utilize EI are always in an advantageous position to communicate and resolve the educational and social problems of their students.3 Maturity is a wide-ranging term and considered as a psychological term used to specify how a person reacts to the situations or background in a suitable way. There is one more term EM that is a part of the term maturity, which means the state at which the mental and emotional capabilities of an individual are fully developed.10 Therefore, it has been suggested that it would be more reasonable to emphasize EM than EI. EM travels much more than only intelligence. EM means a “higher state of consciousness, guided by what one senses, feels, and intuits, and one’s heart”.11 EM is also defined as how well one is able to respond to situations, control emotions, and behave in an adult manner when dealing with others.12 EMs go along with the following five principles: 1) every negative emotion in a person is a consequence of his or her past experiences, 2) adults are also fixated with emotions of their childhood, 3) a person’s feelings are individualized, 4) adults being emotionally mature and childlike is a universal fact, and 5) mindfulness, attentional focus, and self-awareness are the key facts about EM.13

Adult learning theories and andragogy

Adult learning is defined as the whole range of official, unofficial, and casual learning events that are undertaken by adults after discontinuing preliminary education and training, which results in the gaining of new information and benefits.14 It has been reported that by adopting older instructional methods, there was a very insignificant development noticed at the completion of the teaching session among adults.15 The worst part of the traditional teaching model has been revealed in the reputed journal Academic Emergency Medicine, in 2014, that learners often feel they already possess more knowledge and skill than their instructor. Thereafter, both learners and instructors of US Army medical school wish to have more proficient and more meticulous instructional strategy to harmonized adult-learning model.15 There is a strong interrelationship between self-directed learning (SDL) readiness and EI.16,17 Similarly, research also establishes the fact that provision of SDL style increases learners’ capability to become strong, self-directed learners.17 It has been reported that emotionally intelligent people are able to lead themselves toward the desired direction, which is actually the contribution of SDL. Again, SDL is an integral part of adult learning.17–20 Andragogy is one of the popular theories among adult learning theories. Andragogy assumes that adults are experienced, independent, and self-directed. Therefore, they can integrate in the learning demand of their everyday need, are interested in immediate problem-centered approaches, and are motivated more internally.21 Globally, medical education involves adults, and it is logical to focus on adult learning theories, especially andragogy.21–25 There are a number of traversing adult learning theories, which can be grouped into six main classes.21,26,27 These include instrumental learning, humanistic transformative learning, social theories of learning, motivational models, reflective models, and situated cognition.21,26,27 SDL and andragogy are considered under humanistic learning theory26 and reported to be the top of the mentioned theories.21,28–32 The term andragogy was first used by the German scholar Alexander Kapp in 1833 to describe the educational theory of the Greek philosopher Plato.33,34 Alexander Kapp used the word andragogy to mention the regular procedure by which adult learners are involved in continuing education to build themselves.35 Furthermore, Kapp did not mention whether he developed the word or borrowed; he also did not develop the theory but rationalizes “andragogy” as the practical necessity of the education of adults.35 The word andragogy resurfaced in 1921 in a statement by Rosenstock in which he contended that adult education required distinct instructors, approaches, and philosophy, and he used the term andragogy to refer comprehensively to these different prerequisites.36 The lookouts of adult learners are significantly different from children; adults learn efficiently when they have a strong internal inspiration to grow a new skill and proficiency to exist in their profession.37 The Canadian Literacy and Learning Network describes the following seven principles of adult learning: 1) adults must want to learn; 2) adults will learn only what they feel they need to learn; 3) adults learn by doing; 4) adult learning focuses on problems and the problems must be realistic; 5) experience affects adult learning; 6) adults learn best in an informal situation; and 7) adults want guidance.37 Andragogy is equally important in medical education like any education, as medical students need to be self-motivated in their education and also in the professional field. Increasing evidence suggests that by adopting andragogy, health care has been improved substantially.26,38,39 Andragogy is the art and science of helping an adult to learn as defined by the eminent scientist Knowles.40 It has been described that instructional efficacy of the teachers and self-motivation of the learners were upgraded and reached the high standard by adopting andragogy.40 There are five conventions upon which andragogy is founded; they are SDL; experience as a source for learning; readiness to learn that becomes oriented to the development of social roles; problem-centered learning; and internal motivation to learn.41 Any experienced medical teacher or facilitator will agree at once that these qualities will always enhance and promote medical education to produce a high-quality holistic doctor.

Adult learning theories and the relation between EI and EM

All these aspects help the students to enhance their motivation as an adult learner; however, the motivated behavior is toned by their emotions.42 Therefore, the importance of their EM needs to be recognized with adult learning and academic achievement. A number of studies suggested to focus on EM than on EI, as EM explores beyond intelligence and refers to a higher state of self-awareness, guided by what one senses, feels and intuits, and one’s heart.11,13,43 It has also been reported that minor portions of common people actually process all their decisions on the basis of true emotion.43 Therefore, it has been noticed that a majority actually kills their emotion alive for existence.43 EI is the understanding of emotions; EM is the application of that knowledge. EI and EM are comparable to knowledge and wisdom.44 Nevertheless, two eminent scientists, Dr Jeffrey A Cantor and Dr Patricia Cranton, sketched into five different points regarding adults’ learning styles; 1) adults are autonomous and self-directed; 2) goal oriented; 3) relevancy oriented or problem centered, therefore, they need to know why they are learning something; 4) practical and problem solvers; 5) accumulated life experiences.45,46 Andragogy is the instruction method planned for adults to emphasize more on the process and less on the content. Case studies, role playing, simulations, and self-evaluations were reported as the most useful methods, and teachers should play a role of a facilitator but not as a professor with the high level of knowledge.47–49 Definitely, these strategies of action in any classroom in medical education will be extremely helpful. Furthermore, it has been pointed out that adults are natural and have dissimilar motivations for learning than children. Motivations are required: 1) to develop or uphold social relationships; 2) to encounter external anticipation, such as the supervisor expresses that you have to upgrade skill X to save your career; 3) to acquire extraordinary qualities to oblige others, such as administrators frequently attain fundamental skill of first aid to protect their employees; 4) professional advancement; 5) escape or stimulation and 6) “pure interest”.45 It was further deduced that self-actualization was the major cause of adult learning, and the task of the educator was to promote adult learners to grow and accomplish their full potential as emotional, psychological, and intellectual beings.50 It was further prophesied that andragogy would be considered by the “tension between human agency and social structures as the most potent influences on adult learning. Here, andragogy is unconditional, on the side of humanity and the power of the individual to shed the shackles of history and circumstance, in pursuit of learning”.51

Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin (UniSZA)

The Faculty of Medicine, UniSZA, is scheduled to conduct a major revision in the next few years of the undergraduate medical curriculum.52,53 The medical faculty of the UniSZA has evolved with time. It initially started as a faculty of health sciences, offering three diploma programs in radiography, medical laboratory technology, and nursing science. UniSZA was honored with the trust given by the Ministry of Higher Education of the Government of Malaysia to contribute toward the development and improvement of health care by the approval of the University’s medical program in Kuala Terengganu, Terengganu, Malaysia. The approval was granted by the Ministry of Higher Education on February 3, 2009. Faculty had already started the one-degree program, Dietetics (Honors) in 2008; MBBS (Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery) became a part of the program in 2009. In 2011, a Diploma in Physiotherapy was added to the existing diploma programs. It was planned that the faculty of medicine would start to admit new groups of students in another three new programs by 2015 but actually started admittance from the current year 2016. Programs are: 1) Bachelor of Biomedicine, 2) Bachelor of Medical Imaging and Diagnostics, and 3) Bachelor of Nutrition. The first group of 30 MBBS students, admitted in 2009, graduated in August 2014. Therefore, UniSZA medical graduates started working as house officers and serving Malaysia from early 2015. UniSZA has successfully graduated another two batches in 2015 and 2016. Therefore, around 140 medical graduates are serving in Malaysian health system as house officers. Malaysian medical education is usually of 5-year program and 2-year housemanship in hospitals owned by the Ministry of Health, Government of Malaysia.54–57

The purpose of the study

It has been viewed as there is a close association between EM and adult learning skills. Thereafter, the current study intended to evaluate EM scores of the preclinical medical students of Faculty of Medicine, UniSZA and also, to assess the adult learning skills in these subjects and to find out the association between EM and adult learning skills in these medical students. The data were collected using two standardized and validated instruments: 1) EM scale and 2) the adult learning questionnaire. Details of questionnaires are in the “Materials and methods” section. The findings of this study will provide suitable data to redesign the novel educational program to enrich personalities of the medical students. Consequently, these data will be more helpful for UniSZA and Faculty of Medicine to produce high quality professional medical doctors for Malaysian community.

Materials and methods

Study type, population, sampling, and ethics

This was a cross-sectional study conducted on medical students of UniSZA. The study population was from the Faculty of Medicine, UniSZA, preclinical medical students, from Years I and II of academic session 2015/2016. The Universal sampling method was applied as total population was less; at UniSZA, Faculty of Medicine, each year average intake was only 60 for MBBS program. Therefore, the total study population was 126 but only 120 self-administered questionnaires were distributed to the preclinical students of the Faculty of Medicine, UniSZA, because six students participated in the pretested program. Both the questionnaires were in the English language; Malaysian medical students are quite fluent in the English language. Furthermore, in Malaysian medical school as per Malaysia Medical Council and Malaysian Quality Assurance Authority the language of instruction is English. This exercise was carried out soon after the professional development classes, which were part of their curriculum by extending the time for half an hour. Research ethics were strictly maintained, especially regarding confidentiality. Explanation concerning the purpose of the study was given to the participants to utilize their data for research purposes. Prior to data collection, informed written consent was obtained from the management as well as the students of this study. The period of study was from October 2015 to April 2016. This research obtained the ethical approval from UniSZA Research Ethics Committee (UniSZA. C/1/UHREC/628-1 (30); June 16, 2015). The current research was totally anonymous and voluntary.

Questionnaires validation and statistical issue

The data were collected using two standardized and validated instruments. Both the questionnaires were initially developed by other institutes.58,59 1) EM scale was developed by National psychological corporation Kacheri Ghat, Agra, India.58 The principal author Dr. Vidya Bhagat bought the questionnaire from the mentioned institute. 2) The second questionnaire – adult learning questionnaire – was developed by Dr. Muhamad Saiful Bahri Yusoff, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Malaysia.59 The researchers of the present study obtained formal permission to use the validated instrument of adult learning. The instruments were validated many times in different universities of foreign countries and Malaysia, but questionnaires were again pretested and validated for the medical students of UniSZA. Most of the sections of both questionnaires demonstrated acceptable values, with a range between 0.672 and 0.882, which indicated that both instruments possessed good internal consistency and reliability. The evidence of convergent validity was shown by the significant correlations between the items of each section and the overall mean in each section (rs=0.332–0.718; p<0.05).60,61

The “EM scale” contains 48 questions, with 5-point Likert scale (very much =5, much =4, undecided =3, probably =2, and never =1) giving a maximum score of 240 (≥115 = higher EM; 100–115 = normal EM; and <100 = lower EM). The “adult learning questionnaire” contains only six questions, similar to 5-point Likert scale (1= least like you, 2= in between scores of 1 and 3, 3= 50% like you, 4= in between scores of 3 and 5, and 5= most like you). Adult learning scale is a 15-point scale, which varies from -15 to +15 scores distributed on the probability scale. Here, positive scores are the “X” scores and the negative scores are the “Y” scores. Zero is the cutoff point and the scores above the cutoff point are andragogy learning skills and below the cutoff point are pedagogy skills (adult learning score = X - Y). The data were compiled and analyzed using SPSS Version 21. The independent t-test and Pearson’s correlation were used for comparing the data, especially mean. The mean is the average of the numbers: a calculated central value of a set of numbers.

Results

Sociodemographic data

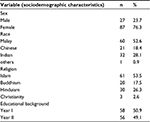

Out of 120 questionnaires distributed among Years I and II preclinical medical students of UniSZA, 114 were returned with a response rate of 95%, excluding the six preclinical students (Years I and II) of the Faculty of Medicine, UniSZA, who participated in the validation program. Among the study participants, 23.7% (27) and 76.3% (87) were males and females, respectively. A total of 52.6% (60), 18.4% (21), 28.1% (32), and 0.9% (1) of the study participants were from Malay, Chinese, Indian, and other races, respectively. A total of 53.5% (61), 17.5% (20), 26.3% (30), and 2.6% (3) study participants have their religion as Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, and Christianity, respectively. Again, the study participants were 50.9% (58) and 49.1% (56) from Years I and II, respectively (Table 1).

| Table 1 Sociodemographic profile of the study participants (n=114) |

Emotion maturity and adult learning scores

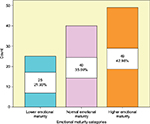

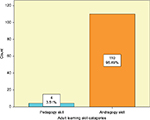

The mean (SD) scores of males and females are 25.70 (4.99) and 25.39 (5.36) for emotional instability, 24.81 (5.54) and 23.91 (5.32) for emotional regression, 24.59 (5.46) and 22.75 (4.59) for social adjustment, 20.22 (4.53) and 19.29 (3.92) for personality disintegration, and 19.15 (3.72) and 19.40 (3.16) for lack of intelligence, respectively. The total mean (SD) scores for EM in males and females are 113.63 (16.72) and 110.86 (15.85), respectively. The mean (SD) scores for adult learning skills in males and females are 4.52 (2.34) and 4.67 (2.80), respectively. There were no statistically significant (p>0.05) mean difference of these aforementioned (EM [p=0.436], adult learning [p=0.804], emotional instability [p=0.788], emotional regression [p=0.445], social maladjustment [p=0.083], personality disintegration [p=0.300], and lack of independence [p=0.727]) scores between males and females (Table 2). UniSZA medical students can be categorized according to the EM level: 21.9% (25), 35.1% (40), and 43% (49) were with low, normal, and high EM, respectively (Figure 1). Again, UniSZA medical students can be categorized according to adult learning skills: 3.5% (4) and 96.5% (110) were under pedagogy and andragogy skills, respectively (Figure 2).

| Figure 1 Emotional maturity categories (n=114). |

| Figure 2 Adult learning skill categories (n=114). |

Correlation between EM and adult learning scores

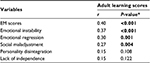

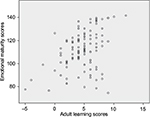

The result showed that there was a statistically significant correlation (Table 3 and Figure 3) between adult learning scores and EM scores (r=0.40, p<0.001). Thereafter, statistically significant (Figure 4) correlation was also observed in emotional instability (r=0.37, p<0.001), emotional regression (r=0.30, p=0.001), and social maladjustment (r=0.27, p=0.004). However, there was no statistically significant correlation (Table 3 and Figure 5) between adult learning scores and personality disintegration (r=0.15, p=0.108) and lack of independence (r=0.15, p=0.122).

| Figure 3 Correlation between adult learning scores and EM scores (n=114). Abbreviation: EM, emotional maturity. |

| Figure 4 Correlation between adult learning scores and emotional instability, emotional regression and social maladjustment (n =114). |

| Figure 5 Correlation between adult learning scores and personality disintegration, and lack of independence (n=114). |

Discussion

The present study group included 114 premedical students of UniSZA, which comprises a larger part of female students. The sociodemographic profile of these study participants includes participant’s racial and religious background. The results of the present study show that irrespective of their demographic background, the study participants showed significantly affected EM, particularly at the initial stage, when they enter the medical realm and try to fit in. A number of earlier studies have supported the findings of the present study.62,63 Similar earlier study also suggested that this process of “fitting in”, stirred heightened sense of anxiety, and sense of escaping.63 As newly admitted students had to make some new tunings in their university life, some new outlines of behavior and social order started, which lead to experience emotional instability.63 These emotions were frequently intense, uncontrolled, and seemingly irrational.63 Time is the best healer, and with time, these emotional behaviors improve as students move to senior levels.63 A number of studies reported that medical students also follow pedagogy learning pattern.64–66 Another study reported that EM was a principal aspect especially as a forecaster of success in essay tests among medical students.67 It also reported that medical students especially undergraduates suffer from high levels of emotional distress, low level of EM, and psychosocial intervention, resulting in improved EM.68,69 Therefore, emotional immaturity takes its toll in learning, transitioning from pedagogy into andragogy.

The forecasted views in the hypothesis that EM has an impact on adult learning skills of medical students were statistically analyzed. The study result shows the significance as per the predicted hypothetical views. The study result has been supported by a number of studies that state that the adult learning is self-directed of the knowledge about the impact of emotion on learning broadly.70–72 Thereafter, emotion cannot be considered to be detached from the learning setting, even evidences suggest that emotion is equally acting in the online situation as an essential component.70–73

Another study compared “young students” and “mature students” and concluded that the senior pupils were more encouraged with modern pedagogical methods such as those concentrating on “employability and immediately relevant competencies are required”.74 Andragogy also shoulders that there are different education physiognomies and necessities for adults than for children, and therefore, instructional strategy for adults must be different from the pedagogical ones used for children.32 Accordingly, medical schools should encourage adult learning in budding medical professionals. Psychological maturity has an impact on entering into andragogy learning type.32,75,76 As a person matures emotionally and intellectually, his or her self-concept moves from dependency to self-directing human being.77–80 EM is an integral part of adult learning.81

The five important areas of EM were measured in the present study and correlated. Out of the five major areas of emotional immaturity, two areas, independence and personality disintegration show no statistically significant (p>0.05) correlation. Other areas, emotional instability, emotional regression, and social maladjustment, were statistically significantly (p<0.05) correlated with adult learning. The area of EM that has significantly impacted emotional instability affects the learning area of medical students; this fact has been supported by one of the earlier studies in which neuroticism (emotionally unstable) reacts negatively to academic stress; this factor must have contributed to the low academic performance.81 Social maladjustments also due to immaturity pave a way to pedagogy. One Indian study reported that the prevalence rate of EM (average to low) was 63.38% among health science students,68 whereas the prevalence rate of EM in the present study findings was 78.1%, which was much higher (normal to high maturity level). It has been reported that “medical students who were more intelligent emotionally performed better in both the continuous assessments and the final professional examination”.82 Most of the study participants were found to be either normal (35.1%) or high (43%) in EM.

Therefore, from the study results, researchers can expect that with a high level of maturity UniSZA medical graduates will perform better academically and in real life scenarios as mature practitioners and rational prescribers. In other studies, it was claimed that emotionally mature people are self-aware and possess supervisory skills, improving health care quality.4,83 Hence, UniSZA medical students can be on the good side in Malaysia and hopefully a time will come they will lead health care in Malaysia. “Andragogy – the study of adult education – has been endorsed by many medical educators throughout North America”.9 Another study revealed that medical teachers “need to stop rationalizing our traditional, teacher-centered efforts at the cost of our adult learners and start viewing the adult learner as more than an imaginary character”.84 In the present study, the majority (96.49%) of the respondents follow andragogy. Therefore, the respondents were in the same line of Knowles,50 the “guru of the adult education”.85

Limitations

This is a cross-sectional study and has its inherent limitation. Moreover, the sample size was only 114. Therefore, it is quite difficult to generalize the study findings for the whole country. On the other hand, students’ genetic and intellectual aspects also contribute to their adult learning skills. The present study did not explore these areas because of insufficient time, and no research fund was obtained. Therefore, new extensive research in this regard is advocated to promote and produce more holistic medical doctors for the community.

Conclusion

This research concludes with suggestions that developing awareness of EM and its influence on adult learning will pave a way to develop enriched professional personalities among the medical students. The introduction of such programs may also develop the insight among the mentors of students; thereby, they can mend their mentees’ emotional behavior. The study results support the hypothetical view that there is an association between EM and adult learning skill. Consequently, this result strengthens the hypothetical view of the researchers. The correlation between andragogy and developing awareness regarding EM will then reinforce its application in developing adult educational module, strengthened by leading-edge studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors are much grateful to those medical students of UniSZA, who participated in this study. The authors would also like to extend their heartfelt thanks to all members of UniSZA Human Research Ethical Committee (UHREC), especially to the Chairman Professor Dato’ Dr Ahmad Zubaidi Abdul Latif, MD (UKM), MMED (UM), FRCS (Edinburgh). Dato’ Zubaidi currently holds the position of the Vice-Chancellor of the UniSZA. The authors would also like to express special thanks to Dr. Myat Moe Thwe Aung for her help in analyzing the data obtained in this study. As a final point, the authors express their gratitude to Dr. Zubair M Kamal, Coordinator, Sleep Research Unit, Toronto Western Hospital, University Health Network, Toronto, ON, Canada, for his comment and notes. This research was funded by UniSZA DPU grant.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Psychology Today [webpage on the Internet]. Emotional Intelligence. What Is Emotional Intelligence? Available from: https://www.psychologytoday.com/basics/emotional-intelligence. Accessed July 15, 2016. | ||

Johnson DR. Emotional intelligence as a crucial component to medical education. Int J Med Educ. 2015;6:179–183. | ||

Esposito M. Emotional Intelligence and Andragogy: The Adult Learner. Thonburi: 2005:1–14. Available from: https://belleville.lindenwood.edu/education/andragogy/andragogy/2011/Esposito_2005.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2016. | ||

Birks YF, Watt IS. Emotional intelligence and patient-centred care. J R Soc Med. 2007;100(8):368–374. | ||

Monroe ADH, English A. Fostering emotional intelligence in medical training: the select program. Am Med Asso J Ethics. 2013;15(6):509–513. | ||

Jansen CA, Moosa SO, Van Niekerk EJ, Muller H. Emotionally intelligent learner leadership development: a case study. S Af J Educ. 2014;34(1):1–6. | ||

Uchino R, Yanagawa F, Weigand B, et al. Focus on emotional intelligence in medical education: from problem awareness to system-based solutions. Int J Acad Med. 2015;1(1):9–20. | ||

Jensen S, Kohn C, Rilea S, Hannon R, Howells G. Emotional Intelligence: A Literature Review. Department of Psychology, University of the Pacific; 2007. Available from: http://www.pacific.edu/Documents/library/acrobat/EI%20Lit%20Review%202007%20Final.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2016. | ||

Misch DA. Andragogy and medical education: are medical students internally motivated to learn? Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2002;7(2):153–160. | ||

Aggarwal H. Emotional Intelligence: What’s the Difference between Maturity and EQ? Available from: https://www.quora.com/Emotional-Intelligence-Whats-the-difference-between-maturity-and-EQ. Accessed August 26, 2016. | ||

TrueNorthPartnering. Emotional Intelligence Vs Emotional Maturity. Available from: http://www.truenorthpartnering.com/sites/default/files/Emotional%20%20intelligence%20vs.emotional%20maturity.pdf. Accessed August 26, 2016. | ||

Your Dictionary [webpage on the Internet]. Emotional Maturity; 2016. Available from: http://www.yourdictionary.com/emotional-maturity. Accessed August 26, 2016. | ||

Vajda P [webpage on the Internet]. Emotional Intelligence or Emotional Maturity? Management Issues. Available from: http://www.management-issues.com/opinion/6811/emotional-intelligence-or-emotional-maturity/. Accessed August 26, 2016. | ||

Institute of Education. Study on European Terminology in Adult Learning for a Common Language and Common Understanding and Monitoring of the Sector. University of London; 2010:1–6. Available from: http://languageforwork.ecml.at/Portals/48/documents/lfw-web_item-3a_nrdc_european-adult-learning-glossary-rept_en.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2016. | ||

De Lorenzo RA, Abbott CA. Effectiveness of an adult-learning, self-directed model compared with traditional lecture-based teaching methods in out-of-hospital training. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11(1):33–37. | ||

Yang GF, Jiang XY. Self-directed learning readiness and nursing competency among undergraduate nursing students in Fujian province of China. Int J Nurs Sci. 2014;1(3):255–259. | ||

Radnitzer KD. Emotional Intelligence and Self-Directed Learning Readiness among College Students Participating in a Leadership Development Program. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; 2010. | ||

Akerjordet K, Severinsson E. Emotionally intelligent nurse leadership: a literature review study. J Nurs Manag. 2008;16(5):565–577. | ||

Cadman C, Brewer J. Emotional intelligence: a vital prerequisite for recruitment in nursing. J Nurs Manag. 2001;9(6):321–324. | ||

Vitello-Cicciu JM. Exploring emotional intelligence: implications for nursing leaders. J Nurs Adm. 2002;32(4):203–210. | ||

Abela J. Adult learning theories and medical education: a review. Malta Med J. 2009;21(1):11–18. | ||

Cantillon P, Hutchinson L, Wood D. ABC of Learning and Teaching in Medicine. John Wiley & Sons; 2011. Available from: http://edc.tbzmed.ac.ir/uploads/39/CMS/user/file/56/scholarship/ABC-LTM.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2016. | ||

Knowles MS. The Adult Learner: A Neglected Species. Huston: Gulf Publishing Company; 1973. Available from: http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED084368.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2016. | ||

Knowles MS, Holton IIIEF, Swanson RA. The Adult Learner: The Definitive Classic in Adult Education and Human Resource Development. 8th ed. New York: Routledge; 2015. | ||

Barr RB, Tagg J. From teaching to learning – a new paradigm for undergraduate education. Change. 1995;27(6):12–26. | ||

Taylor DC, Hamdy H. Adult learning theories: implications for learning and teaching in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 83. Med Teach. 2013;35(11):e1561–e1572. | ||

Amstutz DD. Adult learning: moving toward more inclusive theories and practices. New Dir Adult Contin Educ. 1999;1999(82):19–32. | ||

Wilcox S. Fostering self-directed learning in the university setting. Stud High Educ. 1996;21(2):165–176. | ||

Merriam SB. Andragogy and self-directed learning: pillars of adult learning theory. New Dir Adult Contin Educ. 2001;2001(89):3–14. | ||

Ong I. Andragogy and self-directed learning: pillars of adult learning theory. UPLB J. 2009;6:1–2. | ||

TEAL Center Staff. The U.S. Department of Education, Office of Vocational and Adult Education. Adult Learning Theories. 2011. Available from: https://teal.ed.gov/sites/default/files/Fact-Sheets/11_%20TEAL_Adult_Learning_Theory.pdf. Accessed July 16, 2016. | ||

Clardy A. Andragogy: Adult Learning and Education at Its Best? ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED492132. Towson, MD: Psychology Department, Towson University; 2005. Available from: https://www.lindenwood.edu/education/andragogy/andragogy/2011/Clardy_2005.pdf. Accessed July 16, 2016. | ||

Henschke JA. Beginnings of the history and philosophy of andragogy 1833–2000. In: Wang VCX, editor. Integrating Adult Learning and Technologies for Effective Education: Strategic Approaches. New York: Information Science Reference; 2010:1–30. Available from: https://www.lindenwood.edu/education/andragogy/andragogy/2011/Clardy_2005.pdf. Accessed July 16, 2016. | ||

Smith MK [webpage on the Internet]. Andragogy, the Encyclopaedia of Informal Education; 1996, 1999, 2010. Available from: http://infed.org/mobi/andragogy-what-is-it-and-does-it-help-thinking-about-adult-learning/. Accessed July 16, 2016. | ||

Knowles MS [webpage on the Internet]. Theory Name: Andragogy; 1984. Available from: http://web.cortland.edu/frieda/id/IDtheories/42.html. Accessed July 16, 2016. | ||

Nottingham Andragogy Group. Towards a Developmental Theory of Andragogy, Adults: Psychological and Educational Perspective. Nottingham: Department of Adult Education, University of Nottingham; 1983. Available from: https://www.lindenwood.edu/education/andragogy/andragogy/2011/Nottingham_1983.pdf. Accessed July 16, 2016. | ||

Canadian Literacy and Learning Network [webpage on the Internet]. Principles of Adult Learning; 2016. Available from: http://www.literacy.ca/professionals/professional-development-2/principles-of-adult-learning/. Accessed July 16, 2016. | ||

Koons DC [webpage on the Internet]. Applying Adult Learning Theory to Improve Medical Education. UCHC Graduate School Masters Theses; 2004:1–73. Available from: http://digitalcommons.uconn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1050&context=uchcgs_masters. Accessed July 16, 2016. | ||

Aziz VM. Andragogy, and Psychiatric Workplace-Based Assessments. Available from: http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/pdf/Andragogy%20and%20WPBAs%20-%20RCPsych%20in%20Wales%20%20summer%20newsletter%202015%20Victor%20Aziz.pdf. Accessed July 16, 2016. | ||

Knowles MS. Andragogy in Action. Applying Modern Principles of Adult Education. San Francisco: Jossey Bass; 1984. | ||

Knowles MS. The Adult Learner: A Neglected Species. 6th ed. Houston, TX: Gulf Publishing; 1990. | ||

Bhagat V. Appreciation and recognition of professional skill and its impact on emotional toning of motivational behavior. Int J Humanit Soc Sci Invent. 2014;3(3):47–50. | ||

TrueNorthPartnering. Emotional Intelligence and Emotional Maturity. Available from: http://www.truenorthpartnering.com/sites/default/files/Emotional%20%20intelligence%20and%20emotional%20maturity_0.pdf. Accessed on August 28, 2016. | ||

Beard M. What is the Difference between Emotional Intelligence and Emotional Maturity? 2012. http://inspirebusinesssolutions.com/blog/what-is-the-difference-between-emotional-intelligence-and-emotional-maturity. Accessed August 28, 2016. | ||

Cantor JA. Delivering Instruction to Adult Learners. Toronto: Wall & Emerson; 1992:35–43. | ||

Cranton P. Working with Adult Learners. Toronto: Wall & Emerson; 1992:13–15;40–63. | ||

Kearsley G. Andragogy (M. Knowles). Washington, DC: George Washington University; Available from: http://web.stanford.edu/dept/SUSE/projects/ireport/articles/general/Educational%20Theories%20Summary.pdf. Accessed July 16, 2016. | ||

Kearsley G [webpage on the Internet]. Explorations in Learning & Instruction: The Theory into Practice Database; 2000. Available from: http://www.media.gwu.edu/~tip/. Accessed July 16, 2016. | ||

Kearsley G [webpage on the Internet]. Explorations in Learning & Instruction: The Theory into Practice Database; 1998. Available from: http://www.gwu.edu/~tip/index.html. Accessed July 16, 2016. | ||

Knowles MS. The Modern Practice of Adult Education: From Pedagogy to Andragogy. 2nd ed. New York: Cambridge Books; 1980. | ||

Pratt DD. Andragogy after twenty-five years. In: Merriam SB, editor. Update on Adult Learning Theory. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1993. | ||

Malaysian Qualifications Agency. Code of Practice for Program Accreditation. 2nd ed. Petaling Jaya, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia: Malaysian Qualifications Agency; 2008. | ||

Malaysian Qualifications Agency. Code of Practice for Institutional Audit. 1st ed. Petaling Jaya, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia: Malaysian Qualifications Agency; 2008. | ||

Rahman NI, Aziz AA, Zulkifli Z, et al. Perceptions of students in different phases of medical education of the educational environment: Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2015;6:211–222. | ||

Ismail S, Salam A, Alattraqchi AG, et al. Evaluation of doctors’ performance as facilitators in basic medical science lecture classes in a new Malaysian medical school. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2015;6:231–237. | ||

Bhagat V, Haque M, Simbak NB, Jaalam K. Study on personality dimension negative emotionality affecting the academic achievement among Malaysian medical students studying in Malaysia and Overseas. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2016;7:341–346. | ||

Haque M, Zulkifli Z, Haque SZ, et al. Professionalism perspectives among medical students of a novel medical graduate school in Malaysia. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2016;7:1–16. | ||

National Psychological Corporation (NPC) [homepage on the Internet]. Largest House of Developing the Various Psychological and Educational Tests. Available from: http://www.npcindia.com/. Accessed June 17, 2016. | ||

Yusoff MSB. Reliability and validity of the adult learning inventory among medical students. Educ Med J. 2011;3(1):e22–e31. | ||

Nunnally JC. Psychometric Theory. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1978. | ||

Barman MP, Hazarika J, Kalita A. Reliability, and validity of Assamese version of EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire for studying the quality of life of cancer patients of Assam. World Appl Sci J. 2012;17(5):672–678. | ||

Extremera N, Fernández-Berrocal P. The role of student’s emotional intelligence: empirical evidence. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa. 2004;6(2):1–16. | ||

Sharma B. Adjustment and emotional maturity among first year college students. Pak J Soc Clin Psychol. 2012;9(3):32–37. | ||

Nilsson MS, Pennbrant S, Pilhammar E, Wenestam C-G. Pedagogical strategies used in clinical medical education: an observational study. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:9. | ||

Halari MM, Halari CD, Olaleye AO, Williams IE. Identifying learning pattern among medical students and their preferred mode of study. Am Sci Res J Eng Tech Sci. 2016;18(1):142–152. | ||

Beetham H, Sharpe R. Rethinking Pedagogy for a Digital Age: Designing for 21st Century Learning. London: Routledge; 2013. | ||

Singh D, Kaur S, Dureja G. Emotional maturity differentials among university students. J Phys Educ Sport Manag. 2012;3(2):41–45. | ||

Swamy SV, Rao S, Ancheril A, Vegas J, Balasubramanian N. Prevalence of emotional maturity and effectiveness of counselling on emotional maturity among professional students of selected institutions at Mangalore, South India. J Biol Agric Healthc. 2014;4(6):33–36. | ||

Sarita, Kavita, Sonam. A comparative study of an emotional maturity of undergraduate & postgraduate students. Int J Appl Res. 2016;2(1):359–361. | ||

Brookfield SD. The Skillful Teacher: On Technique, Trust and Responsiveness in the Classroom. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Inc; 2006. | ||

Lehman R. The role of emotion in creating instructor and learner presence in the distance education experience. J Cognit Affect Learn. 2006;2(2):12–26. | ||

Lipman M. Thinking in Education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1991. | ||

Cleveland-Innes M, Campbell P. Emotional presence, learning, and the online learning environment. Int Rev Res Open Distrib Learn. 2012;13(4):269–292. | ||

Yoshimoto K, Inenaga Y, Yamada H. Pedagogy and andragogy in higher education – a comparison between Germany, the UK and Japan. Euro J Educ. 2007;42(1):75–98. | ||

Cercone K. Characteristics of adult learners with implications for online learning design. AACE J. 2008;16(2):137–159. | ||

Herod L. Adult Learning from Theory to Practice. 2012. Available from: http://learn.coleggwent.ac.uk/pluginfile.php/86374/course/section/7450/adult_learning.pdf. Accessed June 17, 2016. | ||

Knowles M. Andragogy: An Emerging Technology for Adult Learning. London: Routledge; 1996. Available from: https://www.nationalcollege.org.uk/cm-andragogy.pdf. Accessed June 17, 2016. | ||

Sabbaghian Z [webpage on the Internet]. Adult Self-Directedness and Self-Concept: An Exploration of Relationship. Available from: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=8244&context=rtd. Accessed June 17, 2016. | ||

Bejot DD [webpage on the Internet]. The Degree of Self-Directedness and the Choices of Learning Methods as Related to a Cooperative Extension Program. Available from: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=7870&context=rtd. Accessed June 17, 2016. | ||

Knowles MS. The Modern Practice of Adult Education (Revised and Updated). New York: Cambridge; 1980. Accessed from: http://www.dehfsupport.com/Andragogy.pdf. Accessed June 17, 2016. | ||

Bhagat V, Nayak RD. Neuroticism and academic performance of medical students. Int J Humanit Soc Sci Invent. 2014;3(1):51–55. | ||

Chew BH, Zain AM, Hassan F. Emotional intelligence and academic performance in first and final year medical students: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13:44. | ||

Bulmer Smith K, Profetto-Mcgrath J, Cummings GG. Emotional intelligence and nursing: an integrative literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46(12):1624–1636. | ||

Vaughn LM, Baker RC, DeWitt TG. The adult learner: a misinterpreted species? Acad Med. 2000;75(3):215–216. | ||

Norman GR. The adult learner: a mythical species. Acad Med. 1999;74(8):886–889. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.