Back to Journals » Advances in Medical Education and Practice » Volume 12

Comparisons Between Preclinical and Clinical Dental Students’ Perceptions of the Educational Climate at the College of Dentistry, Jazan University

Authors Aldowsari MK , Al-Ahmari MM , Aldosari LI, Al Moaleem MM , Shariff M, Kamili AM, Khormi AQ, Alhazmi KA

Received 20 October 2020

Accepted for publication 1 December 2020

Published 11 January 2021 Volume 2021:12 Pages 11—28

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S287741

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Md Anwarul Azim Majumder

Mannaa K Aldowsari,1 Manea M Al-Ahmari,2 Lujain I Aldosari,3 Mohammed M Al Moaleem,4 Mansoor Shariff,5 Ahmed M Kamili,6 Abdullah Q Khormi,6 Khaled A Alhazmi6

1Department of Pediatric Dentistry and Orthodontics, College of Dentistry, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; 2Department of Periodontics and Community Dental Sciences, College of Dentistry, King Khalid University, Abha, Saudi Arabia; 3Prosthetic Department, College of Dentistry, King Khalid University, Abha, Saudi Arabia; 4Department of Prosthetic Dental Science, College of Dentistry, Jazan University, Jazan, Saudi Arabia; 5Department of Prothetic Dentistry, King Khalid University, Abha, Saudi Arabia; 6College of Dentistry, Jazan University, Jazan, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence: Mohammed M Al Moaleem

Department of Prosthetic Dental Science, College of Dentistry, Jazan University, Jazan, Saudi Arabia

Tel +966 550599553

Email [email protected]

Purpose: The aim of this study was to compare the preclinical and clinical undergraduate dental students’ perceptions of their educational climate (EC). In addition it will be compared with other local and international studies.

Materials and Methods: Students enrolled in their third and fourth years (preclinical phase) and students in their fifth and sixth years (clinical phase) of the Bachelor of Dental Science at the University of Jazan, Saudi Arabia, were invited to complete a WhatsApp media survey, which included demographics and the Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure (DREEM). This scale measured students’ overall perceptions of the EC in five domains: learning, teaching, academic self-perception, atmosphere, and social self-perception. Data were analyzed with Student’s t-tests and ANOVA to compare between and within groups.

Results: A total of 272 participants, 140 (51.5%) preclinical and 132 (48.5%) clinical students,took part in the study. Students were generally positive about their learning climate, with overall DREEM scores of 125.19 and 126.21 (preclinical) to 124.10 (clinical) out of a possible score of 200 phases. Student’s perceptions of teaching (26.18± 3.24/72.72%) and atmosphere (28.08± 5.29/63.82%) were the highest and lowest scores, respectively, and both scores were positive.

Conclusion: No differences between the preclinical and clinical phases of the curriculum point to the structure of learning, teaching, academic, social self-perception in health professional degrees. Further research should investigate the weak points in the social and atmospheric climate.

Keywords: educational climate, teaching, DREEM, student perception, education programs

Background

Educational climate (EC) is a broad concept. Here, education encompasses teaching and learning, whereas the environment encompasses everything that surrounds these factors. EC can be described as anything involved with educational institutions.1 In 1998, the World Federation of Medical Education highlighted EC as a target area for the evaluation of health and dental education programs.2

In 1997 Roff et al developed the Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure (DREEM). It is a multidimensional and multicultural instrument that can measure the five separate fundamentals of EC, namely, students’ perceptions of learning (SPL), students’ perceptions of teachers (SPT), students’ perceptions of atmosphere (SPA), students’ academic self-perception (SASP), and students’ social self-perception (SSSP).3,4 DREEM can be used to highlight the weaknesses and strengths of an educational institution, compare the performance and success of dental schools, and contrast the different levels of study and gender among students.2,4 In addition, this tool can be used to help amend the curriculum, compare present and past programs, and evaluate the effectiveness of college curriculums.5,6 Furthermore, DREEM can help health and dental schools to distinguish their priorities,4–8 while comparing their performance and productivities against their peers. The results of this comparison can be educationally insightful.7,9

The College of Dentistry in Jazan University was established in 2006. It is one of three governmental dental schools in the southern part of the KSA. The Bachelor of Dental Science (BDS) program consists of six years, which are divided into the following: two years of premedical/dental preparatory and basic medical subjects and four additional years consisting of two years for preclinical subjects, and two years related to the clinical subjects. The total credit hours for the BDS program is 197, divided into three parts, 59 credit for the first two years, and the remaining credit hours are divided into 72 credit hours for the preclinical phase, and the residual 66 credit hours are for the clinical phase subjects. Most of those subjects consist of theory lectures, seminars, practical, clinical simulation, and clinical subjects.10 In addition, all dental students must complete a full year in an internship program, in which the graduated dentist will practice the different dental specialties as a general practitioner.

The use of DREEM is important in providing a consistent method for global comparisons among dental schools, thereby leading to the standardization of ECs.3,8 DREEM has been successfully used in studies of heath science institutes throughout the world. It carried out studies of the EC in dental colleges in Saudi Arabia,9,11–17 Europe,18–23 Asia,24–31 Africa,32 North America, and the Caribbean.33–35 Previous dental local and worldwide studies are presented in (Table 1).

|  |  |  |  |  |  |

Table 1 Summary of Dental Student’s Perception Using DREEM Inventory for EC at Different Local and Worldwide Studies |

A major drawback has always been insufficient knowledge of students’ perceptions about their academic learning and instruction in the BDS program as well as the overall educational atmosphere of the institution. The objectives of the current study were to build a reference point of information of the student’s perceptions of their educational climate by using DREEM inventory in the College of Dentistry, Jazan University. Another goal was to identify whether there were any differences between preclinical and clinical phases in students’ perceptions in EC. In addition, this study sought to understand the association between variables, such as age, secondary school type, gender, total cumulative grade point average (CGPA), and family monthly income of the students. Finally, we aimed to assess the strengths and weaknesses of the institution’s EC and compare our results with local and international studies.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants

All dental students at the College of Dentistry, Jazan University from the third to sixth (final) year in the BDS programs were the target of the study population and participated in this cross-sectional descriptive study. The DREEM questionnaires were distributed via WhatsApp to the study subjects who had been enrolled at the end of the 2019–2020 academic year. Consent forms were signed by all students at the beginning of the questionnaire. Ethical approval was gained from the Ethical Committee of the College of Dentistry, Jazan University (CODJU, 19,211). This study is in accordance with the guidelines of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.36

Inclusion Criteria and Participant Collection

The inclusion criteria for this study included participants over 18 years of age, in the third year or above in the BDS program, and present at the time of the study. The participants were asked to evaluate the EC. The DREEM questionnaires were distributed to all participating students via WhatsApp through group leaders of both the male and female students.

Instruments and Outcome Measures

The validated Arabic version of the DREEM questionnaire was used as recommended by Al-Namankany et al,37 and Al-Nasser et al.38 The Arabic translation of the 50-item DREEM questionnaire was used to measure students’ perceptions of the educational climate in this study.9,12–16 The DREEM contains 50 questions relating to a range of topics directly relevant to EC.3–6 The inventory was delivered through student’s WhatsApp media. Students were asked to read each statement carefully and to respond using a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.” It was emphasized that each participant should apply the items to their current learning situation and respond to all 50 questions.

Items were scored as follows: 4 for “strongly agree”; 3 for “agree”; 2 for “uncertain”); 1 for “disagree”; and 0 for “strongly disagree”. However, nine of the 50 items (numbers 4, 8, 9, 17, 25, 35, 39, 48, and 50) were negative statements and should be scored as (0 for strongly sgree), (1 for agree), (2 for uncertain), (3 for disagree), (4 for strongly disagree). The 50-item DREEM has a maximum score of 200 indicating the ideal EC as perceived by the registrar.3,4 The total or overall DREEM score (Table 2) consisted of five subscales (Table 2) and items (Table 2), which provides an approximate guide for interpreting the subscales below the appendix.

|

Table 2 Guide for the Interpretation of the Total DREEM and the Five DREEM Subscales and 50 Items.3,4,38,39 |

Data Statistical Evaluations

The completed questionnaires were collated form the WhatsApp social program via the phone for both preclinical and clinical students. The answers to each question were entered using codes 0 to 4. The responses of the nine negative items were reverse coded to analyze the results appropriately.3,4,6,33 We used the IBM Statistical Package for alsothe Social Sciences (SPSS) Statistics version 22 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) program for statistical analysis. The parameters were assessed via the Shapiro–Wilks test, and the results showed that the parameters conformed to the normal distribution. During the evaluation of the study data, the comparisons of quantitative data, descriptive statistical methods (mean, standard deviation), and categorical variables were presented in frequencies and percentages. One-way ANOVA was used in the intergroup comparisons of parameters, and the Tukey's HDS test was used to determine the differences among the group parameters (CGPA and monthly income). Student’s t-test was used in the intergroup comparisons of parameters (gender, age, type of school, level of education). The Fisher–Freeman–Halton test and the chi-squared test were used to compare the qualitative data, and the statistical significance was evaluated at the level of p<0.05.

Results

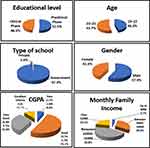

Out of 300 questionnaires that were disseminated by WhatsApp, only 272 completed questionnaires were collected from the students with a total response rate of 91%. The highest response rate was among the clinical phase students at 94%. Demographic data are presented in (Figure 1). There were 140 (51.5%) preclinical respondents and 132 (48.5%) clinical phase students. The age of participants ranged from 19 to 25 years. The average age was 22.4±1.4, with 46.3% between 19 and 22 years of age, and 53.7% between 23 and 25 years of age. Based on the type of high school, 97.4% and 2.6% of the students graduated from government and private high schools, respectively. As for gender, 156 (57.4%) were male, and 116 (42.6%) were female. The response rates based on CGPA were 18 (6.6%); 139 (51.1%); 86 (31.6%), and 29 (10.7%) for pass, good, very good and excellent, respectively. Based on monthly family income, 3.7% were below SAR 3000; 30.5% were from SAR 3000 to 10,000; 43.8% were from SAR 10,000 to 15,000; and 22.1% of the participants were over SAR 15,000.

|

Figure 1 Demographic profiles of respondents (n=272). |

The total mean and SD of the DREEM items was 125.19±15.11, although it was slightly higher among preclinical 126, 21±16, 02 than the clinical phase 124,1±14,0. The mean and SD of subscales based on the original values of the overall DREEM, preclinical and clinical subscales ranged between 63.82% and 74.08% (Table 3).

|

Table 3 Mean Scores of the Total DREEM, Preclinical and Clinical Phases and Its Subscales |

Table 4 shows the mean and SD of the DREEM items and subscales for items scoring the highest and <2. The highest recorded value was 3.17±0.57 for question number two regarding SPT (“The teachers are knowledgeable”). The minimum registered value was 1.35±0.92 for question number 35 in the SPA subscale (“I find the experience disappointing”). Other item scores ranged between two and three.

|

Table 4 Dental Students’ Mean Item DREEM Scores (n=272) |

The results of Student’s t-test showed that the overall mean of DREEM items and subscales SPL, SPT, SASP, SPA, and SSSP had no statistically significant differences in terms of gender, age groups (19–22 and 23–25), type of high school (government or private) and educational level (preclinical or clinical phase), and the p-values were >0.05 (Table 5). Moreover, no statistically significant difference was observed between the total mean of DREEM items and subscale scores of SPL, SPT, SPA, and SSSP in relation to the UGPA (p>0.05). A significant difference was observed between the UGPA of SASP scores (p:0.021; p<0.05). Post hoc comparisons were conducted to determine the origin of significance. The SASP mean scores of “pass” were statistically significantly lower than those of “very good” and excellent (p1:0.048; p2:0.016; p<0.05) (Table 5). Regarding the family’s monthly income level, the results of the ANOVA test showed that the total mean score of DREEM items was significant at (p:0.032; p<0.05). Post hoc comparisons were conducted to determine the origin of significance. The overall DREEM score of families with monthly income of over SAR 15,000 was significantly higher than families with incomes of SAR 10,000–15,000 (p:0.024; p<0.05). There was no significant difference between other income levels in terms of overall DREEM scores (p>0.05) (Table 5). A significant difference was observed between the family’s monthly income level in terms of SASP scores (p:0.004; p<0.05). The average SASP score of students whose family’s monthly income was above SAR 15,000 was significantly higher than the students whose family’s monthly income was between SAR 3000 and 10,000, and SAR 10,000 and 15,000 (p1:0.007; p2:0.017; p<0.05). There was no significant difference between other income levels in terms of SASP scores (p>0.05) (Table 5). According to the family’s monthly income level, the SPA score was significant at (p:0.032; p<0.05). Post hoc comparisons were conducted to determine the origin of significance. The SPA score of families with monthly income of over SAR 15,000 was significantly higher than families with income of SAR 10,000–15,000 (p:0.022; p<0.05). There was no significant difference between other income levels in SPA scores (p>0.05) (Table 5), nor any statistically significant difference were detected between SPL, SPT and SSSP scores according to the family’s monthly income level (p>0.05) (Table 5).

|

Table 5 Mean Score of DREEM Based on the Demographic and Education Characteristics of Dental Students (n=272) |

No statistically significant differences were observed between the preclinical and clinical phase (Table 6) and between genders in terms of total DREEM score and all the subscale scores of the SPL, SPT, SASP, SPA, and SSSP distributions with (p>0.05).

|

Table 6 Association Between Preclinical and Clinical Phase Students and Educational Characteristics (DOMINE) with the Mean Overall Score of DREEM and Subscale of Dental Students (n=272) |

Discussion

The DREEM is a multidimensional and multicultural tool that can measure the five separate basics of EC namely, learning, teachers, atmosphere, academic, and social self-perception.3 DREEM has been used to highlight the weaknesses and strengths of an EC in several countries, and it has been translated and copied to many languages, such as Arabic,9,12–16 Turkish,18 Romanian,19 Spanish,21 Greek,22 Dutch23 and Urdu.24–30 The current study measured the perceptions of the learning climate among a sample of Saudi dental students from the University of Jazan. Overall, students across preclinical and clinical phases of the BDS program were more positive than negative about the domains of their EC as measured by the DREEM (Table 3). The mean value of DREEM for all dental students (125.19±15.11) was higher than their counterparts in other local dental colleges in Saudi Arabia,9,12–16 in the college of medicine and medical science at Umm Al-Qura University, Saudi Arabia,39 and in other colleges in Turkey, Greece, and India.18,22,30 However, it was equal to other countries using the same instrument’s rating scale in Romania, Spain, Germany, Nepal, Pakistan, India, and Australia.19,21,23–25,28,29,

The mean DREEM values for preclinical and clinical phases were 126.21±16.02 and 124.1±14.0 (Table 3), which are lesser values than those recorded among similar phases in studies conducted by Al-Saleh et al,9 in King Saud University (KSU) Riyadh. It was, however, near to the scores obtained among preclinical dental students by Kossioni et al,22 in Greece, Chandran and Ranjan29 in India, Stormon et al,30 in Australia, and by Tisi Lanchares et al,34 in Chile. Higher DREEM scores were registered in preclinical and clinical dental students in Spain by Tomas et al,21 130.6 and 140.0, and New Zealand 143±15.4 and 134±16.5. All the previous studies conducted among dental students, which have used the DREEM scales, found students’ perceptions of the EC were more positive than negative, except for some studies in SA.12,14,15 Those scores were less than 100 and indicated a considerable number of problems.

All students were recruited in this study, except first and second year students and the response rate was 91%, which was significantly higher than some of the earlier studies conducted in SA, KSU-Riyadh which recorded response rates of 60.73% and 52%,9,11 Dammam University reported 72% and 81.7%,13,15 but equal or slightly lower than studies conducted at Taibah University Al Madinah, and Al Munawara with 91%, 97–100% and 97%.12,14,16 A high response rate was also recorded in dental schools worldwide (Turkey 96.69%;18 Spain 80%;21 Nepal 100%;24 Pakistan 70%;25 India 96%,26 87%28 and 83.7%,29 Nigeria 95%;28 Australia 90%,33 Chile 91.1%,34 and New Zealand 82–94%).35

Figure 1 and Table 5 show that there were no significant differences between the two phases of the dentistry curriculum, ie, the preclinical phase (years 3 and 4) and the clinical phases (years 5 and 6). The DREEM values for the preclinical students’ scores were higher (more positive) in the domains of the learning and atmospheric climate. This parallels with the research findings reported among dental professions previously in Greece, Germany, India, Australia, and Chile.22,23,30,33,34 This is an important finding because of the association between students’ perceptions of their learning climate and their well-being as they transition to the clinical years of the program.

Changes in perceptions between the preclinical and clinical phases are not surprising as learning, teaching, atmosphere, and social climate in dentistry shift from mostly lecturing and tutoring modalities in preclinical years (years 3 and 4) to the addition of clinical teachers in a clinical patient-based setting in later clinical years (years 5 and 6) of the BDS program. These are very different learning environments with different requirements and expectations for students compared with other nonclinical degrees. Clinical-based requirements, working hours, and examinations are more in the clinical years and may influence the student’s perceptions of their EC as well as their stress levels. Previous literature has found that both academic and clinical requirements and workload were a significant source of stress for students.31 The addition of clinical-based learning, which mainly depends on more patient contact, responsibility, and requirements may introduce stressors for dental students and could result in a more negative perception of the climate.33

The relation of different demographic parameters of our participants regarding the total DREEM scores, EC subscales, and specific items and are presented in Figure 1 and Table 5. No significant differences existed in terms of secondary school type, different age groups, CGPA, and family monthly income. This finding is consistent with those of previous studies.13,18 However, significant differences (p=0.021) were observed between CGPA students in SASP between the different levels of family monthly incomes in the overall total DREEM and SASP and SPA scores. A similar finding was detected by Jnaneswar et al,28 in relation to the SPT subscale. Al-Ansarie et al,15 stated that improved SPL increased the number of high achievers, whereas increased perception of problems in SPA and SSSP, resulted in a greater number of low achievers and failing students.

Regarding gender, no significant differences affecting the EC of students’ self-perceptions in this college. Similar findings were obtained among dental students in SA,9,12,15 and worldwide in Turkey,18 Greece,22 and Pakistan.25 However, gender differences were found in other dental studies using DREEM scales and carried-out in India;28,29 Australia,33 and New Zealand.35

The scores recorded for the DREEM subscales were 31.36±4.69; 26.18±3.24; 21.92±3.52. 28.08±5.29; and 17.64±3.03 for SPL, SPT, SASP, SPA, and SSSP, respectively. Those values were slightly higher than the values recorded in studies carried out in SA,12–16 and equal or parallel with the values recorded by Al-Saleh et al,9 in Riyadh, SA and outside SA in the European countries of Romania,19 Spain,21 Greece,23 Germany,23 in Pakistan,25 in India,27,30 and in Chile.34 The DREEM subscales scores of the current study were lesser than that values documented in Nepal, India, Nigeria, Australia, and in New Zealand.24,26,29,32

In the preclinical phase, the student perception for their DREEM subscales values were 31.88±4.99; 26.26±3.44; 21.98±3.77; 28.26±5.40; 17.83±3.08 for SPL, SPT, SASP, SPA, and SSSP, respectively Table 5. Those values are equal or in the same range of values recorded in Greece, India, Australia, Chile,22,30,33,34 and lesser than values in Nigeria.32 Values of SPL/30.82±4.29; SPT/26.09±3.03; SASP/21.86±3.25; SPA/27.89±5.18; and SSSP/17.45±2.97 of the DREEM subscales for the clinical phase students were close to or the same as in studies conducted in Spain,21 India,30 and Chile,34 but higher than in Greece,22 India,27 and lesser than values recorded in Nigeria.32 The interpretation of all the abovementioned values or scores for DREEM subscales are in the more positive perception. These values were moving in the right direction; feeling on the positive side; a more positive attitude; and not too bad for SPL, SPT, SASP, SPA and SSSP, respectively.

Among the 50 DREEM questions, only a few items received scores under two, and the lowest scored questions was related to SPA Table 4, in which the student’s experiences were disappointing. One possible reason for this is that our students are studying separately; it may also be related to the social habits of the country. Other items were related to the SPT. This is not surprising since most of the teachers are not Arabic speakers. The teaching methodology is completely in English and most of our students (97.4%) graduated from governmental high schools. The important point is in that most of the previous local,12–15 and international,18,21,23,24,27,30,32,34,35 studies concluded that preclinical and clinical dental students face stress during their studies. This is in total agreement with the results of this study, since the score of the question in relation to the support of stressed students was 1.87 to 0.98, which is considered problematic. Studies published in SA by Ahmed et al,14 and Mahrous et al,16 recorded a score of <1 for the same question. In addition, a single study in SA by Al-Ansari et al,15 recorded less than <1 in a question related to the same issue, which was “”Enjoyment outweighs the stress of the courses in the college“.

In the current cross-sectional questionnaire-based study, we compared the EC between preclinical and clinical dental students. The DREEM scale and its subscales did not contain questions directly related to the dental educational program and climate, such as items including such clinical requirements as “”filling of carious teeth, removable and fixed prostheses, extraction of badly broken down teeth, root canal treatments, and a community program of services, and preventive programs of oral hygiene.” The lack of these items was considered a limitation in this study and in the design of DREEM items and subscales.

Conclusion

The following conclusions can be drawn from this cross-sectional study:

The overall, preclinical and clinical students DREEM scores for dental students perceived the EC to be positive and without any significant differences between gender and phases of study.

Our scored values were equal or higher than those of local and international dental studies.

No association between variables such as age, secondary school type, gender, total CGPA, and family monthly income of the students was determined for SPs.

Future studies should focus on Items that revealed negative aspects, such as the experiences with the registrar, irritation with course organizers and the level of students’ stress. It was indicated by participants that teachers ridiculed the registrars, they were authoritarian, and became angry during teaching sessions.

A change in attitude and style is necessary to make the EC congenial for the students and to mold them into competent authorities. Furthermore, improved support systems for staff and preclinical/clinical students would help to overcome most of the deficiencies in the institution.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Salam A, Akram A, Bujang AM, et al. Educational environment in a multicultural society to meet the challenges of diversity. J App Pharm Sci. 2014;4(09):110–113.

2. The Executive Council of WFME. International standards in medical education, assessment and accreditation of medical schools’- educational programs. A WFME position paper. Med Educ. 1998;32(5):549–558. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2923.1998.00302.x

3. Roff S, McAleer S, Harden RM, et al. Development and validation of the Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure (DREEM). Med Teach. 1997;19(4):295–299.5. doi:10.3109/01421599709034208

4. Roff S, McAleer S, Ifere OS, Bhattachar S. A global diagnostic tool for measuring educational environment: comparing Nigeria and Nepal. Med Teach. 2001;23(4):378–382. doi:10.1080/01421590120043080

5. Al-Hazimi A, Al-Hyiani A, Roff S. Perceptions of the educational environment of the medical school in King Abdul Aziz University, Saudi Arabia. Med Teach. 2004a;26(6):570–573. doi:10.1080/01421590410001711625

6. Bassaw B, Roff S, McAleer S, et al. Students’ perspectives on the educational environment, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Trinidad. Med Teach. 2003;25(5):522–526. doi:10.1080/0142159031000137409

7. Al-Hazimi A, Zaini R, Al-Hyiani A, et al. Educational environment in traditional and innovative medical schools: a study in four undergraduate medical schools. Educ Health. 2004b;17(2):192–203. doi:10.1080/13576280410001711003

8. Hammond SM, O’Rourke M, Kelly M, Bennett D, O’Flynn S. A psychometric appraisal of the DREEM. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12:2–6. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-12-2

9. Al-Saleh S, Al-Madi EM, AlMufleh B, Al-Degheishem A. Educational environment as perceived by dental students at King Saud University. Saudi Dent J. 2018;30:240–249. doi:10.1016/j.sdentj.2018.02.003

10. Jazan University. Vice Deanship For Development, Policies and Procedures Manual, College of Dentistry, Jazan University, Saudi Arabia. Available from: https://www.jazanu.edu.sa/dent/media/sites/9/2020/09/Policy-and-Procedure-Manual-2019-2020-%D9%85%D8%B6%D8%BA%D9%88%D8%B7.pdf?x98620. Accessed January 6, 2021.

11. Halawany HS, Al-Jazairy YH, Al-Maflehi N, Abraham NB, Jacob V. Application of the European-modified dental clinical learning environment inventory (DECLEI) in dental schools in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Eur J Dent Educ. 2017;21(4):e50–e58. doi:10.1111/eje.12218

12. Al-Samadani KH, Ahmad MS, Bhayat A, Bakeer HA, Elanbya M. Comparing male and female dental students’ perceptions regarding their learning environment at a dental college in Northwest, Saudi Arabia. Eur J Gen Dent. 2016;5:80–85. doi:10.4103/2278-9626.179556

13. Farooqi FA, Moheet IA, Khan SQ. First year dental students’ perceptions about educational environment: expected verses actual perceptions. Inte J Development Research. 05(06):4735–4740.

14. Ahmad MS, Bhayat A, Fadel HD. Comparing dental students’ perceptions of their educational environment in Northwestern Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2015;36(4):477–483. doi:10.15537/smj.2015.4.10754

15. Al-Ansari MA, Tantawi M. Predicting academic performance of dental students using perception of educational environment. J Dent Educ. 2015;79:30. doi:10.1002/j.0022-0337.2015.79.3.tb05889.x

16. Mahrous M, Al Shorman H, Ahmad MS. Assessment of the educational environment in a newly established dental college. J Educ Ethics Dent. 2013;3:6–13. doi:10.4103/0974-7761.126935

17. Al-Shamrani SM. Evaluation of the unified pre-health sciences program by dental students and interns in the College of Dentistry, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. S Dent J. 2002;14:3–6.

18. Alraweei MA, Shahin S, Al Moaleem MM. Analyzing students’ perceptions of educational environment in New Dental College, Turkey using DREEM Inventory. Biosci Biotechnol. 2020;13.

19. Stratulat SI, Octav Candel S, Tăbîrţă A, Checheriţă LE, Costan VV. The perception of the educational environment in multinational students from a dental medicine faculty in Romania. Eur J Dent Educ. 2020;24:193–198. doi:10.1111/EJE.12484

20. Batra M, Malčić AI, Shah AF, et al. Self-assessment of dental students’ perception of learning environment in Croatia, India and Nepal. Acta Stomatol Croat. 2018;52(4):275–285. doi:10.15644/asc52/4/1

21. Tomas I, Millan U, Casares MA, et al. Analysis of the ‘educational climate’ in Spanish public schools of dentistry using the Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure: a multicenter study. Eur J Dent Educ. 2013;17:159–168. doi:10.1111/eje.12025

22. Kossioni AE, Varela R, Ekonomu I, Lyrakos G, Dimoliatis IDK. Students’ perceptions of the educational environment in a Greek Dental School, as measured by DREEM. Eur J Dent Educ. 2102;16:e73–e78. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0579.2011.00678.x

23. Ostapczuk MS, Hugger A, de Bruin J, Ritz-Timme S, Rotthoff T. Students’ perceptions of the educational environment in a German dental school as measured by the Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure. Eur J Dent Educ. 2012;16(2):67–77. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0579.2011.00720.x

24. Vakil N, Singh A. Student’s perceptions of the educational environment at a Dental College of Jammu region, using Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure (DREEM) inventory. Global Research Analysis. 2019;8:146.

25. Zafar U, Daud S, Shakoor Q, Chaudhry AM, Naser F, Mushtaq M. Medical students’ perceptions of their learning environment at Lahore Medical and Dental College Lahore. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2017;29(4):328–334.

26. Motghare V, Upadhya S, Senapati S, Lal S, Paul V. Perceptions of freshman dental students regarding academic environment. J Indian Assoc Public Health Dent. 2019;17:224–229. doi:10.4103/jiaphd.jiaphd_179_18

27. Methre ST, Methre TS, Borade NG. Educational environment in first year BDS and BPT students. Int J Contemporary Med Res. 2016;3(11):3163–3166.

28. Jnaneswar A, Suresan V, Jha K, Das D, Subramaniam GB, Kumar G. Students’ perceptions of the educational environment measured using the Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure inventory in a dental school of Bhubaneswar city, Odisha. J Indian Assoc Public Health Dent. 2016;14:182–187. doi:10.4103/2319-5932.181899

29. Chandran CR, Ranjan R. Students’ perceptions of educational climate in a new dental college using the DREEM tool. Adv Med Educ Prac. 2014;5:177–184.

30. Thomas BS, Abraham RR, Alexander M, Ramnarayan K. Students’ perceptions regarding educational environment in an Indian dental school. Med Teach. 2009;31:e185–e188. doi:10.1080/01421590802516749

31. Babar MG, Hasan SS, Ooi YG, Ahmed SI, Wong PS, Ahmad SF. Perceived sources of stress among Malaysian dental students. Int J Med Educ. 2015;6:56–61. doi:10.5116/ijme.5521.3b2d

32. Idon PI, Suleiman IK, Olasoji HO. Students’ perceptions of the educational environment in a New Dental School in Northern Nigeria. J Educ Practice. 2015;6(8):139–147.

33. Stormon N, Ford PJ, Eley DS. DREEM‐ing of dentistry: students’ perception of the academic learning environment in Australia. Eur J Dent Education. 2018;1–7.

34. Tisi-Lanchares JP, Barrios-Piñeiro L, Henríquez-Gutiérrez I, Durán-Ojeda G. The learning environment at a public university in Northern Chile: how is dental education perceived by students? Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq. 2017;29(1):36–50. doi:10.17533/udea.rfo.v29n1a2

35. Kang LA, Foster VR. Changes in students’ perceptions of their dental education environment. Eur J Dent Educ. 2015;19(2):122–130. doi:10.1111/eje.12112

36. World Medical Association. Declaration: WMA Declaration of Helsinki-ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects; 2008. Available from: http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/index.html.

37. Al-Namankany A, Ashley P, Petrie A. Development of the first Arabic cognitive dental anxiety scale for children and young adults. World J Meta-Anal. 2014;2(3):64–70. doi:10.13105/wjma.v2.i3.64

38. Al-Nasser L, Yunus F, Ahmed A. Validation of Arabic version of the modified dental anxiety scale and assessment of cut-off points for high dental anxiety in a Saudi population. J Int Oral Health. 2016;8(1):21–30.

39. Zaini R. Use of Dundee Ready Educational Environment (DREEM) for Curriculum Needs Analysis in the Faculty of Medicine and Medical Sciences at Umm Al-Qura University, Saudi Arabia. Masters dissertation, Centre for Medical Education, University of Dundee; 2003.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.