Back to Journals » Advances in Medical Education and Practice » Volume 14

Call the on-Call: Authentic Team Training on an Interprofessional Training Ward – A Case Study

Authors Zelić L, Bolander Laksov K, Samnegård E , Ivarson J , Sondén A

Received 20 April 2023

Accepted for publication 29 July 2023

Published 11 August 2023 Volume 2023:14 Pages 875—887

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S413723

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Prof. Dr. Balakrishnan Nair

Lana Zelić,1 Klara Bolander Laksov,2 Eva Samnegård,1 Josefine Ivarson,3 Anders Sondén1

1Department of Clinical Science and Education, Karolinska Institutet, Södersjukhuset, Stockholm, Sweden; 2Department of Education, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden; 3Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

Correspondence: Lana Zelić, Department of Clinical Science and Education, Karolinska Institutet, Södersjukhuset, Alfred Nobels allé 23, 141 52, Huddinge, Stockholm, Sweden, Tel +46 708777459, Email [email protected]

Purpose: There is a disconnect between how healthcare teams commonly are trained and how they act in reality. The purpose with this paper was to present a learning activity that prepares healthcare students to authentic teamwork where team members are fluent and move between different localities, and to explore how this setting affects learning.

Methods: A learning activity “Call the On-Call” consisting of two elements, workplace team training where team members are separated into different locations, and a telephone communication exercise, was created. A case study approach using mixed methods was adopted to explore medical-, nurse-, physiotherapy- and occupational therapy students and supervisor perspectives of the effects of the learning activity. Data collection involved surveys, notes from reflection sessions, a focus group interview, and field observations. Thematic analysis was applied for qualitative data and descriptive statistics for quantitative data. The sociocultural learning theory, social capital theory, was used to conceptualize and analyse the findings.

Results: The majority of the students (n=198) perceived that the learning activity developed their interprofessional and professional competence, but to a varying degree. Especially nursing students found value in the learning activity, above all due to increased confidence in calling a doctor. Physio- and occupational therapy students lacked the opportunity to be active during the telephone exercise, however, they described how it increased their interprofessional competence. Authenticity was highlighted as the key strength of the learning activity from all professions. Concerns that team building would suffer as a result of splitting the student team proved unfounded.

Conclusion: The learning activity created new opportunities for students to reflect on interprofessional collaboration. Constant physical proximity during training is not essential for effective healthcare team building. Splitting the student team during training may in fact enhance interprofessional learning and lead to progression in interprofessional communication.

Keywords: interprofessional training, interprofessional communication, learning activity, authentic teamwork, social capital theory

Introduction

Healthcare of the future requires interprofessional collaboration.1 As a consequence, several interprofessional education (IPE) initiatives have been taken in medical schools globally.2 The educational initiatives include lectures, seminars, simulation exercises and clinical placements in, for example, interprofessional training wards (IPTWs).2 At IPTWs, supervised students from two or more healthcare professions train together, taking care of real patients, with the objective of developing collaborative competencies and, in the end, improving health outcomes.2–4 A core idea behind IPTWs is that “interprofessional skills cannot be taught by others, but be learnt in interaction with others”.5 This is consistent with Kolb’s theory, experiential learning, that active engagement in real-world experiences and reflection is critical to fostering clinical skills and critical thinking, as well as shaping attitudes.6

Social capital theory is the learning theory commonly used to justify IPE.7 According to this theory, if students are given the possibility to invest in social relations, their social capital will promote knowledge sharing between the members of the healthcare team.7 For such a sharing of knowledge to happen, a safe learning environment at the IPTW is essential.8 In line with this, it has been considered vital that students work together in stable student teams in the IPTW without competing activities.9 Stable healthcare teams are, however, not an authentic setting, because the only team member that is normally anchored to the ward is the nurse. Physicians, physiotherapists, and occupational therapists commonly have parallel duties outside the ward, and even more so during on-call hours.10 The fact that team members are seldom in the same location, places special demands on the members’ professional skills and interprofessional collaboration – not least the ability to communicate. Structured communication over the phone eg in patient reports according to SBAR (Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation) has proved to be of great importance for patient safety, but health profession students are insufficiently prepared for such interprofessional communication.11,12 Thus, the established organisation of the IPTW does not prepare students for the complexities of authentic teamwork. When searching the literature, however, it becomes evident that this is not a problem only connected to IPTWs. In general, there is a lack of knowledge on how healthcare teams are trained, or should be trained, given complexities such as team membership fluidity, rotation of members, and multiple forms of communication.13

To address this problem, we created a new learning activity (LA), Call the On-Call, where team members are fluent and move between different localities. The focus of Call the On-Call was collaboration when not all team members were present on the ward, including interprofessional communication over the telephone. The aim of this paper was to present and to explore students’ and supervisors’ feedback and perspectives about Call the On-Call. Furthermore, to understand in a broader sense how splitting the healthcare team during training can affect professional and interprofessional learning and team development. Social capital theory was used to conceptualise the challenges and understand the results.7

Context of the Study

The study was conducted on an IPTW at Södersjukhuset, a large general hospital with approximately 560 beds in Stockholm, Sweden. At the ward during the study period, students from four professions were taking care of patients by working side by side in two teams for two weeks taking care of patients who underwent planned orthopaedic surgeries. Each team consisted of four nursing students, one physiotherapy student, two medical students, and one occupational therapy student. The students came from three different medical universities. The nursing, physiotherapist and occupational therapy students were all in their final (sixth) semester of undergraduate education. The medical students were in the seventh semester of eleven of their undergraduate education. Both nursing students and medical students had prior training in using SBAR during simulation, but not in authentic interprofessional setting in practise.

The supervisors on the ward were two nurses, one resident orthopaedic surgeon, one physiotherapist, and one occupational therapist. The nurse, physiotherapist and occupational therapist supervisors were permanent supervisors at the IPTW, while the resident surgeon supervisors were placed according to a rolling schedule. In the evening, the nurses supervised all student professions. The learning outcomes of the IPTW specified that the students, together with their team, should be able to analyse and meet the patients’ needs and evaluate their treatment, nursing, and rehabilitation. In addition, they had to show the ability to communicate and collaborate with patients and family members, as well as with their own and other professions.14 At the end of each shift students reflected on their own and other professions’ competence, using Gibbs´ reflection cycle to increase learning.15

Like in all experiential workplace-based learning, learning at an IPTW depends on the context in which the students find themselves.16,17 At the IPTW at Södersjukhuset, the medical students had fewer profession-specific tasks on the ward during the evenings, especially compared to the nursing students, and reported in local surveys that the evening shift was not as relevant for them. This was reinforced by the fact that the medical students did not have a medical supervisor present during the evening shifts.

Methods

Study Design

A case study approach was adopted to explore the effects of the LA using a mixed-method strategy.18–20 The case was defined as what happened all the way from when the students started the evening shift up to when they left the ward after the evening reflection session. Abduction was used as the research logic, ie deduction and induction were alternated to gain a deeper understanding of the LA.20 Deduction was used to formulate research questions and a questionnaire with Likert scales, based on the authors’ propositions about how the LA could influence team building and learning. Induction was used at a later stage to work through open answers, reflections, the focus group interview, and observations. From these empirical data, new understandings were formed. Detailed, in-depth data were obtained through multiple sources, using mixed methods as described below.21,22 The data were studied and analysed by applying a sociocultural lens.

Participants in the Study

All students (n=325) that were placed at the IPTW during two semesters were invited to participate in the study.

The Learning Activity: Call the on-Call

The intended learning outcomes of the LA are shown in Box 1. The LA began with a joint afternoon patient handoff report given by the students who had the day shift at the IPTW. Thereafter, the student healthcare team was split up, with the medical students following the evening on-call orthopaedic surgeon around the hospital, and the others continuing to work in the ward in accordance with the authentic organisation. The medical students’ learning activities during the evening shift included assessing patients in the orthopaedic wards and emergency department and assisting surgery – all under the supervision of the on-call orthopaedic surgeon. All the medical students carried their own pagers, through which they always had to be reachable. If the remaining students (primarily the nursing students) needed to consult a physician, they were instructed to first call the medical students. There were also simulated short written cases relating to real patients at the IPTW in case there was no real need to consult the medical students. The focus of the LA was on medical students and nurses for two reasons, firstly, the LA intended to counteract the lack of professional activities for medical students during the evening shift, secondly, it is common for nurses to call doctors during on-call hours, while physiotherapists and occupational therapists rarely need to make such emergency phone calls. It was decided, however, that the physio- and occupational therapist students would be observers during the telephone exercise to learn more about the role of the nurse and the doctors during the on-call work and the importance of structured patient reports. The simulated cases concerned common acute conditions such as postoperative infections, urinary retention, anaemia, etc. The over-The-phone patient reports had to be structured according to SBAR.11 To enable the nursing supervisor and the rest of the student team to follow the communication, a speakerphone was used by the nursing student on the ward calling the medical student. Feedback was given to the nursing students at the end of the phone call according to a structured template. At the end of the evening shift, the medical students joined their original student team at the IPTW for feedback, to have their questions answered, and to participate in an evening reflection. The reflection session was done without a supervisor present, it was semi structured with pre-written questions setting focus on interprofessional telephone communication, how the learning activity had affected teamwork and what they had learned.

|

Box 1 The Intended Learning Outcomes for the Learning Activity Call the On-Call |

Data Collection

The research questions were examined through the collection of both quantitative and qualitative data. Questionnaires with open-ended questions were given to students and supervisors. The questionnaires were specifically designed for the purpose, one for students and one for supervisors (see Supplement 1). Face and content validity of the questionnaires was ensured by testing the questionnaires on representative responders in a pilot study. The questionnaire responses were tied to a five‐point Likert scale, ranging from 5 (strongly agree) to 1 (strongly disagree). The students´ questionnaires were filled in and collected on the last day of each IPTW period. The questionnaire forms and informed consent were placed in the same envelope. The supervisors’ questionnaires were collected continuously during the semesters. To gain deeper understanding of students´ perspectives of the LA, students (eight at a time) were asked to write down their reflections at the LA’s evening reflection session. These notes were collected after each reflection session. To gain similar in-depth data from the supervisors a semi-structured focus group interview was conducted with the supervisors (3 nurses, 1 physiotherapist and 2 physicians) took place on one occasion at the end of the study period. The interview guide was constructed with a basis in the thematic analysis of the student data and focused on how supervisors experienced the implementation of the activity, their reflections on how students reacted to it, student learning and professional development. The focus groups interview was conducted in Swedish, recorded and was transcribed verbatim.

The observations were made during the first semester of the study. The final material consisted of field notes from 75 hours of observations of three different teams at the IPTW.

Data Analysis

The data analysis was an iterative process, using all data sources to refine the results.23 A thematic analysis was used to analyse the qualitative data from the evening reflections, the open answers from the supervisors’ and students’ questionnaires, and the interview and observation data.24 The data from each source were initially analysed separately. By reading and re- reading each data set, emerging patterns were condensed into codes and themes. To discuss and reach agreement on the codes and evolving themes, two to three from the research team along with the author held meetings on numerous occasions. The subcategories and themes from the different sources, including observations, began to converge and were not seen as separate entities, thus creating new themes. Descriptive statistics were used for the quantitative data from surveys. The qualitative and quantitative data were set against each other in a triangulation to increase validity and reduce the risk of making systematic errors.22 Citations used in this paper were translated and discussed by the research group, after which a professional language expert was consulted, and proposed changes were discussed in the group again.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical permission for the study was obtained by Swedish Ethical Review Authority, Region Stockholm, Department 5, (2016/1425-31). Participation in the study was voluntary and all participants signed informed consent forms. In particular, the students were informed that a refusal to participate in the study would not affect their grades in the course. Data anonymization was maintained throughout. The informed consent included publication of anonymized responses. The participants were informed that they could withdraw their consent at any time and suspend their participation in the study.

Results

All students (n=325) that were placed at the IPTW during two semesters were invited to participate in the study, of which n=198 (61%) accepted after giving their informed consent. The response rate for nursing students, medical students, physiotherapy students, and occupational therapy students were 58%, 67%, 64% and 54%, respectively. Of the 198 students who responded to the questionnaire, 109 (55%) were nursing students, 50 (25%) were medical students, 25 (13%) were physiotherapy students, and 14 (7%) were occupational therapy students. One physiotherapist, one occupational therapist and seven nurse supervisors also responded to the survey. Entirely simulated cases were used in 94 (58%) of the telephone exercises, a combination of real problems and simulated cases were used in 41 (25%), and entirely real problems were used in 27 (17%). Based on the results Call the On-Call can be divided into two elements: the communication exercise and the divided team. Both parts generated learning and had effects on the interprofessional team. Qualitative and quantitative data from both elements were categorised into the five main themes presented below: “Development of professional competence”, “Development of interprofessional competence” and “Effects on teamwork”, “Strengths of the LA” and “Weaknesses of the LA”.

Development of Professional Competence

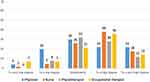

In the survey, 60% (n=54) of the nursing students stated that the exercise had developed their professional knowledge and skills to a high or very high degree (see Figure 1). The corresponding figure for medical students was 47% (n=19), for occupational therapy students 39% (n=5), and for physiotherapy students 19% (n=4).

What the students learned was revealed through observations during the LA, through reflection seminars, and also through the students’ answers to the questionnaire (see Table 1). The following quotes exemplify the learning gained from the communication exercise and the divided team respectively.

Good practice, important to practice communication by telephone and in urgent and unexpected situations. (Medical student, questionnaire)

We felt that we had to make medical priorities ourselves when the medical student was gone. (Nursing student, reflection seminar)

|

Table 1 Professional Competences Developed During the Call the on-Call |

Themes identified in the students’ learning and examples of each theme are shown in Table 1.

Six out of the nine supervisors felt that the exercise developed the students’ professional knowledge and skills to a high or very high degree. The supervisors all highlighted knowledge and skills linked to the telephone communication exercise. The following quote is from one of the nurse supervisors:

Just like practicing technical medical skills, students need to practice making and receiving calls in order to get better at it. (Nursing supervisor, questionnaire)

Development of Interprofessional Competence

Sixty-nine percent (n=9) of the occupational therapy students perceived that the exercise, to a high or very high degree, increased their knowledge of other professions’ skills (see Figure 2). The corresponding figure for nursing students was 60% (n=56), for physiotherapy students 54% (n=12), and 52% for medical students (n=23).

Examples of the interprofessional abilities the students developed from Call the On-Call are presented in Table 2.

|

Table 2 Interprofessional Competences Developed by the Call the on-Call |

Despite the fact that the occupational therapy and physiotherapy students did not actively participate in the communication exercise, they described it as enlightening.

It was instructive to discuss the doctor’s and nurse’s perspective of the conversation. (Occupational therapy student, reflection seminar)

At the reflection seminars, several examples emerged of the students gaining an increased understanding of the importance of collaboration between the professions, and how important communication was for the quality of care and patient safety.

I learned how important it is to communicate with each other and that you take help from each other and each other’s experiences. (Medical student, questionnaire)

Five of the nine supervisors felt that the LA, to a high or a very high degree, increased the students “knowledge of other professions’ skills”. The focus of the supervisors’ comments was the professional roles during on-call work and the changed conditions when the healthcare team was divided during Call the On-Call:

Call the On-Call creates a greater understanding of the need for each other, what knowledge the others have, and what you can ask the other professions to do. (Nursing Supervisor, questionnaire)

Effects on Teamwork

In the survey, 56% (n=60) of the nursing students stated that the LA developed their abilities for teamwork to a high or very high degree (see Figure 3). The corresponding figure for occupational therapy students was 50% (n=7), for medical students 44% (n=22), and for physiotherapy students 40% (n=10). The LA drew the students’ attention to the difficulties caused by the members of the healthcare team not all working in the same physical space. The following quotes came from a medical student and a nursing student respectively:

I could not answer because I was doing surgery, which meant that my answer was delayed by about 30 minutes. This would have affected the team’s work if the case had been genuine. (Medical student, questionnaire)

I was OK considering the planned care. It was a little stressful when unexpected events and situations happened. (Nursing student, reflection seminar)

Despite this, the students perceived that the work and teamwork worked well on the ward – even when the team was divided. The reasons given for this by the students was categorised into safe space, team collaboration, and preparedness. The students said that they trusted the team, that they felt safe with the team and the supervising nurse, and that they could always call the medical student on-call.

Yes, we helped each other based on the skills we have together. (Physiotherapy student, questionnaire)

The students said the fact that everyone in the team was a student at the same level aided the collaboration – not least when it came to making the telephone call. They also mentioned the importance of the supervisors being close at hand, but at the same time the value of working independently and making their own decisions.

The students said that, through team exercises and working at IPTW before Call the On-Call, they had become aware of, and gained confidence in, the different competencies that existed in the team, which had a central role when the team was divided. They highlighted on several occasions how valuable the entire team’s skills were and that together they came to good and important decisions.

Through collaboration, our experiences complement each other, which means that patients receive good care. (Nursing student, reflection seminar)

When problems arose on the ward, the team solved them by discussing solutions or calling the on-call medical student.

The patient handoff report, given according to the SBAR criteria by the students who had the day shift before the LA, ensured that all the students on the evening shift knew what to do. They planned together and coordinated continuously, which gave them clear goals for the evening. All this contributed to a better preparedness for expected and unexpected situations, which they frequently reflected on at the end of the exercise.

The supervisors did not feel that the LA hampered teamwork at the IPTW. On the contrary, they felt the exercise developed the students’ abilities for teamwork:

They have started talking and laughing with each other. They dare to ask those important questions that are on the tip of the tongue and must come out. The opportunity to reason and make decisions via only verbal communication gave many students increased self-confidence and insight into the skills of others. I believe this insight contributed to many students gaining a greater understanding of what it means to work in teams. (Nursing supervisor, questionnaire)

In the survey, five out of nine supervisors stated that the LA, to a high or very high degree, developed the students’ ability to work as a team.

Strengths of the Learning Activity

The students felt the primary strength of Call the On-Call was its authenticity:

What we train during Call the On-Call will happen all the time. (Nursing student, questionnaire)

The students said that the LA prepared them for future work. Although the IPTW was an authentic ward, they also perceived it was an educational environment adapted to them that made emergency calls feel real, but not too scary. They highlighted the benefits of communication training per se and appreciated how it drew attention to the need for interprofessional collaboration and strengthening of the team.

I learned how important it is to communicate with each other. (Medical student, questionnaire)

Even the students who were not active in the telephone conversations, such as the occupational therapy and physiotherapy students, valued that they could participate and listen to the conversations.

It was exciting to hear what they have been through. Even if you just listen, you learn from other professions. (Occupational therapy student, questionnaires)

The supervisors also emphasised the authenticity and relevance for the various professions of the LA:

The exercise sheds light on the real-life situations to which they will be exposed. (Nursing supervisor, questionnaire)

Weakness of the Learning Activity

The weaknesses of the LA described by the students and supervisors were primarily of an organisational nature, such as staff shortages, inexperienced supervisors on-site, stressful situations in the operating room, or technical problems linked to the authentic environment.

It was difficult to find a time that was purely pedagogical – to find time for learning instead of rushing to the next task. (Nursing supervisor, focus group interview)

Something that also emerged was that the students felt an injustice in the fact that not everyone was could to participate actively in the telephone exercises, and they also wanted to practice these skills more.

Discussion

In this article, we presented and explored a new learning activity (LA) Call the On-Call at an IPTW. The LA consists of two elements: workplace team training where team members are separated into different locations, and a telephone communication exercise. Our main findings are that, even though the LA involved splitting up the student team, it did not impair interprofessional learning (IPL) or team building. On the contrary, it created new situations for IPL and developed the healthcare team.

Students of all professions highlighted authenticity and relevance as primary strengths of the LA. The students also described how the authenticity motivated them to take on the challenges posed by the exercise. The students’ perceptions, therefore, aligned with the previous literature on authenticity and relevance in experiential learning.17,25 Equally convincing as the positive reviews was the absence of negative comments regarding idleness and irrelevant tasks that had previously been common amongst the medical students at Södersjukhuset when evaluating the evening shifts at the IPTW. In reflections, and open answers, the medical students indicated they were given opportunities to develop their medical competences and how to act in different environments during Call the On-Call. Their stories related the practical and cognitive challenges they faced, such as how to handle clothes changes and sterility, as well as incoming phone calls while doing another task. The medical students’ journey through the hospital with the physician gave them an opportunity to develop a deeper understanding of their own profession and of nurses’ role at the ward. The students remaining at the IPTW described increased knowledge of the physician’s role and responsibilities, even regarding things that did not directly affect the activities of IPTW.

Effects on the Student Healthcare Team

Our results imply that the student healthcare team was strengthened by the LA even though the LA involved splitting up the student team. This conflicts with previous studies that emphasise the need for constant physical proximity between students for effective learning at the IPTW.8 To interpret and understand these seemingly contradictory results, social capital learning theory is useful.7 According to social capital learning theory conditions for social relations between the students are created as they learn from and with each other at the IPTW. Investing in these relationships creates social capital, which provides an advantage in the form of knowledge transfer between members of the group. The new knowledge of other professions’ competences provides a basis for understanding how the interprofessional team can collaborate and creates better conditions for defining their own professional role. Greater overall confidence in the professions is created, which students can bring to their future work.

Knowledge of the importance of social relations for learning has led to efforts at most medical universities to strengthen students’ social relationships at the IPTW.8 At the IPTW at focus for this study, the entire first day is devoted to social bonding between student team members. Student teams are stable in the sense that the members are the same during their two weeks at the IPTW, where social ties are strengthened through joint activities such as ward rounds and reflection sessions. Moreover, supervisors work hard to create a permissive learning environment in which everyone can progress. We argue that this set the stage for interprofessional learning and creates the “safe space” that the students highlight in their reflections.26 When the team is divided between different locations during Call the On-Call, the safe space makes them feel confident in their new situations. The students’ invested social capital7 also causes them to spontaneously exchange experiences at the end of their shift.27 Hence, we interpret our results that stable teams are important and have an impact on the “safe space” and learning at the IPTW. What we add to previous understanding is that constant proximity is not necessary if students’ social capital is large enough before the team split up. We look upon Call the On-Call as a LA that deepens students’ knowledge of the different competences in the team and leads to new interprofessional learning, eg, around the difficulties of making decisions when not everyone is present and difficulties with telephone communication.

Social capital is important for telephone calls between nurses and doctors about emergency patients. In previous studies, nurses describe how they dislike calling doctors for various reasons, such as becoming stressed during the conversation, the doctor being difficult to reach, doctors not taking the nurse’s competence seriously, and feeling like they are interfering.28,29 Similar sentiments were expressed by the nursing students in this study. We connote that the gains in social capital contributed a lot to the nursing students valuing the LA higher than the other student professions.

It has been shown that phone calls in healthcare education are of great value, not only for developing skills in communication, but also for learning in general.30 In this study Eppich et al30 argued that learning connected to their learning exercise was driven by positive tensions between those involved. However, the authors raised the possibility that hierarchical differences between professions could have negative effects on learning in similar situations and pointed to the need for studies focusing on interprofessional phone calls. In this study we did not find hierarchical barriers, but, instead, the communication exercise highlighted how dependent each profession was on other professions and how important it was to know how to ask the other professions for help. This is in perfect agreement with Kostoff et al, who show that increased interprofessional competence and improved attitudes toward interprofessional collaboration can be achieved by using the SBAR communication tool.31 Looking beyond IPTWs, the results of this study highlight the potential of social bonds to improve team training, as social capital creates the conditions for introducing complex team exercises similar to Call the On-Call.

The LA activated the students to varying degrees. While this may be seen as a weakness, it was a necessity as one of the rationales of the LA was to even out an uneven distribution of profession-specific tasks among the students. In its design, the LA entailed active learning primarily for the medical students, and, to some lesser extent, for the nursing students. Activity or active experimentation is linked to learning.16,17,32 In line with this, it was the nursing students and medical students who felt that the learning activities developed their professional competence to the highest degree. For the same reason, it was not surprising that only a few physiotherapy students thought their professional competence was enhanced by the LA. This should be borne in mind when introducing similar learning activities. Unless there are good reasons not to, we recommend learning activities that activate student professions equally, for as long as authenticity is kept in focus.

Although the occupational therapy and physiotherapy students were not active during the LA, they still perceived it had developed their interprofessional skills. The reason for this may be that they rarely got to see what happens at evenings and nights between these two other professions. Occupational therapists are usually quite separated from nurses and doctors and therefore probably have a lot to learn from the activity. While these students were not active during the phone call, it was nevertheless a concrete experience of a real situation, followed up with a reflection that had the potential to enhance learning further.30,33 The use of the speakerphone meant that even the professionals who were not active in the conversation learned something by observing and being involved in the feedback and reflection sessions afterwards.

Methodological Considerations

One strength of this study was that the researcher LZ understood the whole context. This was partly due to her role as former supervisor with many years of experience on that particular IPTW, and partly due to her being one of the developers of Call the On-Call. However, it may also be considered a limitation that LZ, who was directly involved with the students and supervisors, could be biased and that this influenced the results. To limit such bias, the interviews were conducted by KBL and the observations were made by JI, who were not directly involved in teaching or supervision at the IPTW. The trustworthiness of the data was maximised by collecting data from several sources. A weakness of the study was that, for mostly unknown reasons, almost a third of the students did not participate in the survey. One reason given for this by the supervisors distributing the questionnaires was the lack of time for the students to fill in the questionnaire in the afternoon when they were distributed. It is difficult to discern how this loss of data may have affected the results, however, since the survey was only one of many data sources included in the analysis to draw conclusions about the LA, it is likely to have had only a minor effect on the results.

The fact that our study only assessed students learning at level 1, according to Kirkpatrick Model of program evaluation, may also be seen as a limitation of the study. However, this study was no designed to evaluate how much student learned from the Call the On-Call and what effect their learning might have on their future work. Instead, our focus was what and how student learned, and how the learning activity affected learning and team building at the IPTW in general. Future studies using different methods will have to address how much learning Call the On-call generates and if students can apply what they learned in practice.

Conclusion

In conclusion we have presented a new learning activity that can be integrated into clinical practice to enhance interprofessional learning. We have shown that all students independent of profession appreciated and learned from the new learning activity, albeit in slightly different ways. Our study highlights authenticity as a key factor for successful experiential learning, and the importance of social capital for effective team training. It is also shown that constant physical proximity of the team members is not essential for effective interprofessional team building if the students have been given the opportunity to invest social capital in the student team.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank all the staff and students at the IPTW who so generously allowed access to their educational practice.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

Miss Lana Zelic and Dr Anders Sondén report grants from The Swedish Research Council, Region Stockholm, during the conduct of the study. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Gilbert JH, Yan J, Hoffman SJ. A WHO report: framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. J Allied Health. 2010;39(Suppl 1):196–197.

2. Thistlethwaite J. Interprofessional education: a review of context, learning and the research agenda. Med Educ. 2012;46(1):58–70. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04143.x

3. Oosterom N, Floren LC, Ten Cate O, Westerveld HE. A review of interprofessional training wards: enhancing student learning and patient outcomes. Med Teach. 2019;41(5):547–554. doi:10.1080/0142159x.2018.1503410

4. Jakobsen F. An overview of pedagogy and organisation in clinical interprofessional training units in Sweden and Denmark. J Interprof Care. 2016;30(2):156–164. doi:10.3109/13561820.2015.1110690

5. Wilhelmsson M, Pelling S, Ludvigsson J, Hammar M, Dahlgren LO, Faresjo T. Twenty years experiences of interprofessional education in Linkoping--ground-breaking and sustainable. J Interprof Care. 2009;23(2):121–133. doi:10.1080/13561820902728984

6. Kolb DA. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Prentice-Hall; 1984.

7. Hean S, Craddock D, Hammick M, Hammick M. Theoretical insights into interprofessional education: AMEE Guide No. 62. Med Teach. 2012;34(2):e78–e101. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2012.650740

8. Hallin K, Kiessling A. A safe place with space for learning: experiences from an interprofessional training ward. J Interprof Care. 2016;30(2):141–148. doi:10.3109/13561820.2015.1113164

9. Pelling S, Kalen A, Hammar M, Wahlström O. Preparation for becoming members of health care teams: findings from a 5-year evaluation of a student interprofessional training ward. J Interprof Care. 2011;25(5):328–332. doi:10.3109/13561820.2011.578222

10. Fernando O, Coburn NG, Nathens AB, Hallet J, Ahmed N, Conn LG. Interprofessional communication between surgery trainees and nurses in the inpatient wards: why time and space matter. J Interprof Care. 2016;30(5):567–573. doi:10.1080/13561820.2016.1187589

11. Müller M, Jürgens J, Redaèlli M, Klingberg K, Hautz WE, Stock S. Impact of the communication and patient hand-off tool SBAR on patient safety: a systematic review. BMJ open. 2018;8(8):e022202. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022202

12. Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet. 2010;376(9756):1923–1958. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(10)61854-5

13. Varpio L, Hall P, Lingard L, Schryer CF. Interprofessional communication and medical error: a reframing of research questions and approaches. Acad Med. 2008;83(10 Suppl):S76–S81. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e318183e67b

14. Ponzer S, Hylin U, Kusoffsky A, et al. Interprofessional training in the context of clinical practice: goals and students’ perceptions on clinical education wards. Med Educ. 2004;38(7):727–736. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01848.x

15. Paterson C, Chapman J. Enhancing skills of critical reflection to evidence learning in professional practice. Phys Ther Sport. 2013;14(3):133–138. doi:10.1016/j.ptsp.2013.03.004

16. Dornan T, Tan N, Boshuizen H, et al. How and what do medical students learn in clerkships? Experience based learning (ExBL). Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2014;19(5):721–749. doi:10.1007/s10459-014-9501-0

17. Yardley S, Teunissen PW, Dornan T. Experiential learning: AMEE Guide No. 63. Med Teach. 2012;34(2):e102–e115. doi:10.3109/0142159x.2012.650741

18. Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:100. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-11-100

19. Järvensivu T, Törnroos J-Å. Case study research with moderate constructionism: conceptualization and practical illustration. Ind Mark Manag. 2010;39(1):100–108. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2008.05.005

20. Rashid Y, Rashid A, Warraich MA, Sabir SS, Waseem A. Case study method: a step-by-step guide for business researchers. Int J Qual Methods. 2019;18:1609406919862424. doi:10.1177/1609406919862424

21. Östlund U, Kidd L, Wengström Y, Rowa-Dewar N. Combining qualitative and quantitative research within mixed method research designs: a methodological review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48(3):369–383. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.10.005

22. Jick TD. Mixing qualitative and quantitative methods: triangulation in action. Adm Sci Q. 1979;24(4):602–611. doi:10.2307/2392366

23. Hammersley M, Atkinson P. Ethnography [Elektronisk Resurs] Principles in Practice. Routledge; 2007.

24. Maguire M, Delahunt B. Doing a thematic analysis: a practical, step-by-step guide for learning and teaching scholars. All Ireland J High Educ. 2017;9(3):1.

25. Lidskog M, Löfmark A, Ahlström G. Students’ learning experiences from interprofessional collaboration on a training ward in municipal care. Learn Health Soc Care. 2008;7(3):134–145. doi:10.1111/j.1473-6861.2008.00181.x

26. Shrader S, Zaudke J. Top ten best practices for interprofessional precepting. J Interprof Educ Pract. 2018;10:56–60. doi:10.1016/j.xjep.2017.12.004

27. Ivarson J, Zelic L, Sondén A, Samnegård E, Bolander Laksov K. Call the on-call: a study of student learning on an interprofessional training ward. J Interprof Care. 2020;1–9. doi:10.1080/13561820.2020.1725452

28. Cadogan MP, Franzi C, Osterweil D, Hill T. Barriers to effective communication in skilled nursing facilities: differences in perception between nurses and physicians. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(1):71–75. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01903.x

29. Tjia J, Mazor KM, Field T, Meterko V, Spenard A, Gurwitz JH. Nurse-physician communication in the long-term care setting: perceived barriers and impact on patient safety. J Patient Saf. 2009;5(3):145–152. doi:10.1097/PTS.0b013e3181b53f9b

30. Eppich WJ, Dornan T, Rethans -J-J, Teunissen PW. “Learning the lingo”: a grounded theory study of telephone talk in clinical education. Acad Med. 2019;94(7):1033–1039. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002713

31. Kostoff M, Burkhardt C, Winter A, Shrader S. An interprofessional simulation using the SBAR communication tool. Am J Pharm Educ. 2016;80(9):157. doi:10.5688/ajpe809157

32. Dornan T, Conn R, Monaghan H, Kearney G, Gillespie H, Bennett D. Experience Based Learning (ExBL): clinical teaching for the twenty-first century. Med Teach. 2019;41(10):1098–1105. doi:10.1080/0142159x.2019.1630730

33. Schmutz JB, Eppich WJ. Promoting learning and patient care through shared reflection: a conceptual framework for team reflexivity in health care. Acad Med. 2017;92(11):1555–1563. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001688

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.