Back to Journals » Advances in Medical Education and Practice » Volume 12

An Induction Programme Used to Improve Confidence General Practitioner Trainees in Managing Hospital Ear, Nose and Throat Emergency Presentations

Authors Kucheria A , Bastianpillai J , Khan S, Acharya V

Received 13 July 2021

Accepted for publication 11 October 2021

Published 8 November 2021 Volume 2021:12 Pages 1285—1291

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S329159

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Dr Md Anwarul Azim Majumder

Anushree Kucheria,1 Johan Bastianpillai,2 Shaharyar Khan,3 Vikas Acharya4

1Royal Berkshire Hospital, Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust, Berkshire, UK; 2Northwick Park Hospital, London North west University Healthcare NHS Trust, London, UK; 3London North west University Healthcare NHS Trust, London, UK; 4Department of ENT Surgery, Northwick Park Hospital, London North west University Healthcare NHS Trust, London, UK

Correspondence: Anushree Kucheria Email [email protected]

Introduction: General practitioners (GPs) encounter many adult and paediatric patients presenting with ear, nose and throat (ENT) complaints. There is a paucity of learning opportunities to develop knowledge and skills in ENT at undergraduate and postgraduate level. GP trainees starting an ENT rotation have very little prior experience, and therefore we recognise a need for an introduction through a focused induction programme. The aim of this study was to understand whether a GP trainee focussed induction programme can improve the confidence of these doctors in managing emergency hospital presentations in ENT.

Methods: An ENT-focussed induction program was created: a didactic teaching program, shadowing period and supervised on-calls. Five GP trainees completed the induction programme. Questionnaires assessed the GP trainees’ confidence in managing common emergency presentations and performing common procedures before and after the induction program. For comparison, questionnaires were given to seven GP trainees who did not complete induction program before starting the rotation and 2 weeks subsequently.

Results: With no induction in place, the mean increase in confidence was by 0.81. In comparison, the GP trainees who did complete the induction program had a mean increase in confidence by 1.2. The induction program had a dramatic increase in confidence in ENT-specific skills which would not have been experienced in other specialties such as flexible nasal endoscopy, post-tonsillectomy bleeding, neck sepsis, stridor and periorbital cellulitis.

Limitations: A small cohort of participants in one hospital were included, thus affecting the reliability of the results.

Conclusion: There was a greater level in confidence in managing ENT presentations of those who completed the induction program, and we recommend a similar structured programme for GP trainees who rotate in ENT. This may have wider implications in fostering interest in postgraduate degrees in ENT and improving the quality of primary care management of ENT complaints.

Keywords: otolaryngology, ENT, general practitioner trainees, induction programs, confidence

Introduction

GP Curriculum and Ear, Nose and Throat

In the National Health Service, general practitioners (GPs) conduct over 300 million consultations per year, with a large proportion of their workload involving patients suffering from ear, nose and throat (ENT) problems. These are estimated to account for around 25% of the adults and 50% of the paediatric presentations to primary care.1

ENT as a curriculum is wide-ranging and includes adult and paediatric cases with an overlap into medicine, surgery, public health, oncology, respiratory and palliative care all of which are relevant for aspiring GPs.2 Therefore, incorporating ENT into education and training programs for GPs may be successful in managing ENT problems in primary care. It is important to have increased ENT exposure as it has shown be to beneficial in that it led to early recognition of difficult problems and therefore, making sure that patients are being appropriately referred for specialist opinion and further investigation. It was shown that less ENT training led to increased referrals to specialists, thus leading to insufficient experience, which can also result in an increased burden on ENT outpatient clinics and referral systems, with patients whose treatments should be well within the competence of a trained GP.3 Therefore, a robust knowledge of common conditions is essential in their training and can ultimately improve patient safety.

Confidence and Competence

Currently, ENT teaching is a formal part of the GP training curriculum, and trainees are expected to attend weekly teaching sessions. This has been set out by the Royal College of General Practitioners.4 The three opportunities to train GPs are, at undergraduate level, during foundation training and in specialty training. Literature suggests that there is a deficit in the content, context and variety of teaching at all three levels, especially compared to other medical and surgical specialties, where more emphasis is placed during undergraduate teaching.4

Powell et al showed that mean duration of ENT training was 8 days and the mean confidence in performing an ENT examination and patient management was significantly lower for ENT in comparison to specialties like cardiology.5

Weekly didactic teaching sessions alone may not be sufficient in aiding GP trainees with the tools to in-run their own ENT emergency clinics and safely manage on-call shifts. The learning curve is steep, and apprenticeship-style “learning-on-the-job” without any formal introduction may push the GP trainees into the deep end too quickly, therefore reducing their confidence and not making full use of their short placement. In the long term, a patient’s first port of call for acute ENT symptoms will often be primary care, therefore there needs to be confidence and competence in assessment and management.2

Confidence and competence are important measures used for appraising their own performance. In the context of doctors in training, competence is defined as what doctors know about their ability and therefore feel comfortable performing these tasks. Confidence is influenced when the doctor’s willingness to complete a task, which is unfamiliar to them. The lack of exposure to the ENT field during doctors’ undergraduate and postgraduate curriculum signifies an unfamiliarity on handling acute emergencies and core skills in this field. Therefore, it seems confidence is more appropriate measure of self-evaluation.6

Induction Programmes in the Literature

Transitions from different parts of training for example from medical student to junior doctor can be tough. Therefore, the advent of induction programs allows doctors to ease into their new roles in an unfamiliar environment. Didactic lectures with two on-call shifts with no previous shadowing for GP trainees rotating through ENT are not sufficient to prepare doctors for their new clinical positions. There is a need for induction programs to evolve. Berridge et al trialled an extended preparation programme combining life support, emergency, clinical skills training and shadowing the outgoing house officer.8

While GP trainees rotate on ENT, they run their own emergency clinics as part of their training. An extended induction program can help them prepare for this. The aim is to perform ENT examinations with confidence, recognising common emergency presentations and their immediate management as well as knowing when to escalate. These emergency clinics are important to their future training as they are similar to GP clinics. Exposure to hospital acute ENT presentations will aid their ultimate roles as GPs and their experience will allow them to recognise red flag signs and symptoms and therefore know when to refer.8 Alongside this, shadowing can help incoming doctors become comfortable with their new role and environment. The shadowing period could be further improved by increasing responsibility in a gradual, progressive fashion. This is based on the principles of Wenger’s social learning theory, where “legitimate peripheral participation” and active engagement is key to successful workplace satisfaction for team members.9 This will allow new doctors to contribute to the patient’s care, initially these tasks do not need to be as central to the function of the team. This will let incoming doctors feel integrated as part of the team and have enhanced participation and preparedness for when they formally start their clinical post.

The aim of this study was to understand whether a GP trainee-focused induction programme can improve the confidence of these doctors in managing emergency hospital presentations in otolaryngology.

Methods

An ENT-specific 2-week induction program was created to aid GP trainees starting their ENT rotation at Northwick Park Hospital to improve their confidence in managing ENT primary as well as secondary care scenarios. Twelve GP trainees took part in this study and completed the questionnaire. This was introduced in accordance with previous trainee feedback who did not feel adequately supported at the start of their post. This was created by the ENT team at Northwick Park Hospital.

This induction program entailed a one-day didactic teaching course on common ENT presentations to primary and secondary care, shadowing a senior for the first 2 weeks during on-call shifts and in clinics, and undertaking their first on-call with a senior SHO shadowing them for support. To evaluate the efficacy of the induction program, pre- and post-induction program questionnaires were made. This questionnaire was specifically created to be able to measure the GP trainees’ self-confidence for these acute emergencies. Questionnaires were also given to GP trainees who had not taken part in the induction program and assessed their confidence before and after their first 2 weeks on the job. GP trainees (n=12) had to rate their confidence in managing different ENT on-call pathologies using a 1–5 Likert scale as shown in Figure 1. The questionnaires were given on the first day of starting their job or the induction program and after 2 weeks of starting the job or last day of the induction program.

Results

Before starting their ENT rotation, seven GP trainees completed the questionnaire and it was found that the mean confidence 1.81 with a standard deviation ± 0.48. After being 2 weeks on the job and not completing the induction programme, the mean confidence rose to 2.61 with a standard deviation ± 0.66 (Figure 2). There was a mean increase in confidence by 0.81. In comparison, before the induction programme and at the start of their ENT rotation, five participants completed the questionnaire and their mean confidence was 1.51 with a standard deviation of ± 0.25. After completing the 2-week induction program, their confidence rose to 3.58 with a standard deviation of ± 0.50 (Figure 2). There was a mean increase in confidence by 2.07.

|

Figure 2 Comparison between overall confidence scores of GP trainees who underwent the induction program and those who did not. |

Overall, this shows that there was an improvement in GP trainees’ confidence scores after 2 weeks on the job regardless of an induction program. There was a greater improvement in confidence seen after induction than without an induction program in place.

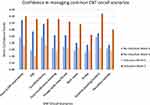

In both groups of GP trainees, Figure 3 shows that baseline confidence in managing these on-call scenarios: flexible nasal endoscopy, post-tonsillectomy bleeding, neck sepsis, stridor and periorbital cellulitis ranged from 1/5 (no confidence at all) to 2/5 (minimal confidence). In contrast to this, baseline confidence for performing general ENT examination, recognising and managing tonsillitis was much higher; trainees were 3/5 (moderately confident).

|

Figure 3 Comparing confidence scores for each ENT scenario with and without induction program. |

The GP trainees completed the induction program had a dramatic improvement to their confidence scores to around 4/5 (highly confident). In comparison, those who did not have an induction, did increase in their confidence to around moderate confidence. This improved induction program seemed to build their confidence to around 4/5 (highly confident) in ENT-specific pathologies and skills. In this induction program, not only were acute ENT pathologies addressed but basic ENT examinations such as otoscopy, neck and lump assessment, throat and nose examination. The same was found for GP trainees with no induction program in place.

Discussion

Induction programs have been useful tools in helping new trainees feel more confident in their new speciality that they are rotating into. Traditional induction programs comprise didactic lectures and perhaps, occasionally skills training. Before this induction program was implemented, didactic lectures about ENT were given and the new GP trainees were to do two on-call shifts with no previous shadowing.

However, induction programs are evolving now by putting the theoretical knowledge into practice in a supported framework. Applying Lave et al’s peripheral participation learning model, this new induction program was created.10 This involves a senior and a senior house officer colleague is available for any queries, shadowing predecessors for on-calls and emergency clinics with interactive teaching sessions. The core curriculum is covered with mixed teaching styles from bedside teaching, case-based discussions and covering the curriculum of common ENT emergencies. This wide variety of teaching styles within this learner-focussed induction program has proven to be beneficial to the GP trainees, which can be seen in the higher increase in their confidence after this induction program in comparison to those who did not.

The largest rise in confidence was seen in ENT-specific pathologies and skills especially after the implementation of the induction program. This specifically includes post-tonsillectomy bleeding, epistaxis, neck sepsis, flexible nasal endoscopy and foreign body extraction. Low baseline confidence in these ENT emergencies could be due to the previous lack of exposure to these pathologies as well as clinical skills training during medical school and foundation training. This is supported by Khan and Saeed that showed that otolaryngology is underrepresented in the medical school curricula.7 Confidence in managing stridor was the lowest of all acute emergencies after the induction program was introduced. Stridor is a real airway emergency. People feel out of their depth and comfort zone, without experiencing this themselves it can be hard to feel confident managing this.

The dramatic increase in confidence after induction program could be due to the shadowing predecessors element of the induction. This was a principle suggested by Berridge et al, which allows incoming trainees to gain helpful tips based on their experiences.8 This allows them to familiarise themselves with a new environment and therefore feel less overwhelmed and focus on the emergency that they are presented with in their initial solo on-calls.

The induction program improved trainees confidence significantly in performing a basic ENT examination. This is especially important for budding GPs who need to be able to differentiate between minor ailments and acute pathologies. Therefore, knowing the fundamentals is important to be able to refer patient appropriately to secondary care. This increase in confidence after induction program can be built upon during their 3-month placement as well as for their future training. Specifically, this induction programme may inspire GP trainees to pursue a special interest in ENT. Therefore, in the long term, inspiring them to gain postgraduate ENT qualification and enabling them to work in hospital and run their own emergency ENT clinics.

Limitations

This study was conducted in one hospital with a small cohort of participants. Baseline confidence scores may have been skewed as we could not account for the GP trainees’ previous experience in ENT. Furthermore, to improve this study, it should be carried out with larger number of participants with multiple different hospitals.

Moreover, confidence was used to measure the success of the induction program using a Likert scale. However, can confidence be used to measure competence? This subjective scale may impact the usefulness of the induction program. Going forward, an objective questionnaire should be designed to help mitigate this. Collecting feedback from the GP trainees’ supervisors would allow us to assess competence as well as confidence.

GP trainees filled their post-induction program when they are starting their 3-month placement. Therefore, to make a good impression for their seniors, they may fill in the questionnaire keep that in mind. This can lead to social desirability bias, and to rectify this, induction program questionnaire could be given at the end of the placement as well as anonymising responses as well.

To further improve this induction program, opinions of other healthcare professionals such as nurses who encounter ENT conditions regularly as well as fully qualified general practitioners to shape the teaching design. Another suggestion is that theoretical knowledge can be delivered online so all trainees start their in-person induction program with similar baseline knowledge. In addition, trainees can spend more time shadowing and having interactive learning experiences.

Conclusion

ENT emergency pathologies commonly present to primary care and therefore it is important GP trainees are confident and competent in discharging as well as referring appropriately. This tailored GP induction program has allowed them to have the confidence to manage the acute pathologies within ENT in a supported network. Ultimately, this supported induction program will hopefully translate in overall improving patient care by reducing inappropriate secondary care referrals and improving efficacy and efficiency of primary care for patients.

Ethics Approval

This research was exempt from ethics approval as it did not use any patient identifying data or undertake work requiring formal ethical approval.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Farooq M, Ghani S, Hussain S. Prevalence of ear, nose and throat diseases and adequacy of ENT training among general physicians. Int J Pathol. 2016;14(3):113–115.

2. Acharya V, Haywood M, Kokkinos N, Raithatha A, Francis S, Sharma R. Does focused and dedicated teaching improve the confidence of GP trainees to diagnose and manage common acute ENT pathologies in primary care? Adv Med Educ Pract. 2018;9:335–343. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S155424

3. Bhalla RK, Unwin D, Jones TM, Lesser T. Does clinical assistant experience in ENT influence general practitioner referral rates to hospital? J Laryngol Otol. 2002;116(8):586–588. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1258/00222150260171542

4. Royal College of General Practitioners. The RCGP curriculum: clinical modules [webpage on the Internet]; 2015. Available from: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/GP-training-and-exams/~/media/Files/GP-trainingand-exams/Curriculum-2012/RCGP-Curriculum-3-15-ENT-Oral-andFacial-Problems.ashx.

5. Powell J, Cooles FA, Carrie S et al. Is undergraduate medical education working for ENT surgery? A survey of UK medical school graduates. J Laryngol Otol .2011;15:896–905. doi:10.1017/S0022215111001575

6. Stewart J, O’Halloran C, Barton JR, Singleton SJ, Harrigan P, Spencer J. Clarifying the concepts of confidence and competence to produce appropriate self-evaluation measurement scales. Med Educ. 2000;34(11):903–909. PMID: 11107014. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00728.x.

7. Khan MM, Saeed SR. Provision of undergraduate otorhinolaryngology teaching within General Medical Council approved UK medical schools: what is current practice? J Laryngol Otol. 2012;126(4):340–344. PMID: 22336001. doi:10.1017/S0022215111003379

8. Berridge E-J, Freeth D, Sharpe J, Roberts CM. Bridging the gap: supporting the transition from medical student to practising doctor – a two-week preparation programme after graduation. Med Teach. 2007;29(2–3):119–127. doi:10.1080/01421590701310897

9. Vijendren A, Trinidade A, Ngu A. Is an ‘Introduction to ENT course’ the answer for safe ENT care? Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;272(4):1021–1025. doi:10.1007/s00405-014-3362-2

10. Lave J, Wenger E Legitimate peripheral participation in communities of practice; 2000:111–126.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.