Back to Journals » Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare » Volume 15

A CiteSpace-Based Analysis of the Development Trends Affecting Clinical Research Nurses in China: A Systematic Review

Received 11 March 2022

Accepted for publication 23 June 2022

Published 17 October 2022 Volume 2022:15 Pages 2363—2374

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S363741

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Ning Wu,1 Mingzi Li2

1Department of Nursing, Shanxi Provincial People’s Hospital, Taiyuan, 030012, People’s Republic of China; 2Peking University, School of Nursing, Beijing, 100191, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Mingzi Li, Peking University, School of Nursing, No. 38 Xueyuan Road, Haidian District, Beijing, 100191, People’s Republic of China, Tel +86 010-82805230, Email [email protected]

Objective: To examine the developmental characteristics and trends affecting clinical research nurses (CRNs) in China and provide a reference for the training and employment of nursing talents in this specialty.

Methods: Literature pertaining to CRNs published from the year in which the database was constructed to 2020 was searched. The databases used were the China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Wanfang, Chinese Biomedical Literature and Weipu, while CiteSpace software was used to conduct a bibliometric analysis of literature quantity, annual distribution, literature journals and regional distribution, literature authors, subject funding status and literature type and keywords. The characteristics and trends affecting CRNs in China were then evaluated using a descriptive analysis.

Results: A total of 3735 pieces of literature were retrieved, and after deduplication and screening, 199 pieces of literature were retained for this study. Overall, the number of publications increased year-on-year. Of these publications, 17 papers (8.5% of the retained papers) were published in the Chinese Journal of Modern Nursing and 9138 papers (69.3%) were published in the top 10 regions according to the location of the first author (of these, 31 [15.6%] were published in Beijing and 42 [21.1%] were funded by scientific research funds). The research fell mainly in the experience summary category, with 107 articles (53.8%) taking this approach. The top five research hotspots were clinical research, good clinical practice (GCP), research nurses, management and clinical trials. The practice and exploration of CRNs were regionalised, accounting for varying degrees of development. CRNs were found to be at the forefront of developments in oncology specialties.

Conclusion: In China, CRNs are currently in a period of rapid development. Research into CRNs mainly involves single-centre studies and lacks financial support. In the future, it will be necessary to increase capital investment, strengthen cross-regional cooperation between authors and institutions to narrow the regional development gap, and promote strict and standardised CRN training models and qualification certification to improve the quality of clinical research nursing.

Keywords: clinical research nurses, CRNs, clinical trials, bibliometric analysis, CiteSpace, development trends

Introduction

With the advent of research-oriented medical care, nursing research has become the main driving force behind the development of the nursing discipline, and the scientific research abilities of nursing staff have attracted much attention. The World Health Organization observes that increasing investment and training in nurses’ scientific research capacities can improve the quality of nursing services and allow the implementation of health strategies.1 Scientific research nurses first originated in the United States (US); the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) defined the term clinical research nurse (CRN; also known as clinical nurse consultant [CNC]). The term CRN relates to nurses who participate in clinical research to a certain extent and who are authorised to represent researchers and participate in the organisation, operation, coordination and management of research projects.2 The position of research coordinator first appeared in the US in the 1980s; this position was mainly held by doctors, inspectors or pharmacists, all with medical backgrounds. The literature on this topic suggests that nurses are the best candidates for research coordinator roles.3 Research coordinators in Europe, the US and other countries have nursing as their professional background. In addition to participating in clinical research to varying degrees, they also engage in researchers’ communication, management and supervision, as well as monitoring the quality of clinical research to ensure that it is properly scientific and of a suitable quality and quality.4 A survey in Japan has found that more than half of medical institutions have research nurses; even smaller medical clinics working on pilot projects will employ research nurses.5 The United Kingdom (UK) and the US clearly stipulate that scientific research nurses must receive relevant training; they can only work after being certified to do so. The NIH, Clinical Research Association, Research Site Management Organization, Cancer Nursing Society and other such institutions have training and qualification certification methods for scientific research nurses.6 Previously, research nurses in the UK, US, Japan and several other countries have played an indispensable role in clinical trials. Chinese nurses’ overall scientific research ability is low; this is mainly related to their lack of scientific research awareness, retrieval skills and statistical knowledge, as well as the limitations presented by their foreign language levels.7 Studies have noted that, in China, the majority of project research conducted in clinical drug trials is undertaken by clinical nurses.8 The training offered to scientific research nurses in China is still at an exploratory stage; however, it appears that scientific research nurses are the inevitable solution to how to solve clinical problems scientifically and effectively.

The CRN role is an emerging profession in China; as such, CRN recruitment and competencies are not yet supported by standardised regulations. Although the history of CRN development in China is not a long one, many questions still need to be answered due to the dramatic increase in clinical drug trial research in China.9 Namely, is the development of China’s CRN workforce commensurate with this increase? What are the CRN-related research hotspots in China? What are the current problems facing the CRN workforce? What are the likely future development trends? With these questions in mind, this paper aims to use CiteSpace bibliometric software to conduct a systematic and comprehensive review of the published literature. The aim is to answer the above questions, examine the development trends and provide a reference for the professional training and employment of CRNs in China.

Data and Methods

Sources

The China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Wanfang, Chinese Biomedical Literature (CBM) and Weipu (VIP) databases were used as literature sources. The search strategy was finalised and constructed after several pre-searches ([subject = nurse] AND [title, keyword and abstract = clinical trial OR clinical study OR drug trial OR new drug]). The matching method was an exact search and the time range was from the year in which the database was constructed to December 2020. All searches were completed on 30 June 2021. A total of 3735 documents were retrieved, and after deduplication and screening, 199 documents were retained as this paper’s research objects.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: the content of the literature had to be relevant to CRNs. There were no limitations placed on the type of study reviewed. The search excluded the following: newsletters, notices, announcements, calls for papers and conference papers; the same study or duplicate publications; literature with incomplete data and literature where the full text was unavailable.

Research Methods

In this paper, we used CiteSpace software to conduct a bibliometric analysis of literature quantity, annual distribution, literature journals and regional distribution, literature authors, subject funding status, literature type and keywords.

The specific parameters of the CiteSpace software were set as follows: time-slicing used the year in which the database was constructed to 2020; years per slice was one; node types were keywords; the threshold was set to the top 50 results (Top50); and a Pathfinder network was applied to the results to show the important features more intuitively.

Statistical Analysis

IBM’s Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) 22.0 was used for statistical analysis. The linear regression equation was fitted with the publication time as independent variable X and the annual literature quantity as dependent variable Y. Indexes such as the number of documents, annual distribution, periodical and regional distribution, authors of documents, funding status of disciplines, types of documents and keywords were described by their frequency and constituent ratio.

Results

Spatio-Temporal Knowledge Mapping of Research Areas

Time-Distribution Mapping

The number of annual publications is an important indicator of the hotness of and development trends affecting related research. The literature, varying with chronology, reflects the overall development of CRNs in China to some extent. The statistical results show that there were 199 publications relating to CRNs in China published between 1992 and 2020. The regression analysis, which has ‘publication time as the independent variable X and annual literature volume as the dependent variable y, shows that R2 = 0.707, indicating that the model fits the data well. The linear regression equation is y = 0.7244 x –1446.5 (F = 48.369, P < 0.01), while the literature volume has increased year-on-year (Figure 1). Further analysis has revealed that the earliest literature that met the criteria appeared in 1992, with only one publication in this year. Since then, the volume of literature has gradually increased, showing a growing trend. The number of publications was highest between 2011 to 2020, with 149 publications accounting for 75% of the total literature. According to Price’s four-stage theory of scientific and technical literature growth, the absolute number of research papers relating to CRNs in China is small, with unstable growth; thus, it belongs to the first stage (ie, the development stage). The current year’s (2022) papers are in the process of being published (five have already been published), so the literature written in 2021 is not included in the yearly analysis.

|

Figure 1 Flow chart of literature selection. |

Spatial Distribution Map

Author Distribution

The 199 papers included in this study involve 539 authors; Table 1 lists the 26 scholars with more than three publications, out of which Chunmei Yang, who published eight papers, is ranked highest. In terms of cross-institutional research, the authors and institutions in each study area show a fragmented distribution, with no obvious clustering and very few collaborations. Additionally, the sharing and mobility of the knowledge and research results are not strong.

|

Table 1 Core Authors and Number of Articles Published in China on CRN |

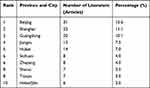

Regional Distribution

Among the institutions occupying the top 10 positions in terms of number of publications (Table 2), seven are general hospitals and three are specialist oncology hospitals. The 199 papers included in this study were counted according to the first author’s region; these 199 papers were written by authors from 180 provinces, cities and autonomous regions. Regarding the number of publications by area, the top 10 regions published 138 papers, accounting for 69.3% of the literature volume (Table 2).

|

Table 2 Top 10 Institutions (Regional Distribution) in Terms of the Number of Publications on CRN |

Published Journals

The 199 papers included in this study have come from 86 journals; of these, the top 10 (in terms of publication volume) account for 63 publications (38%). Most of the journals with a high publication volume are special journals with a great influence in the field of nursing and pharmacology (Table 3); they include Chinese Nursing Research, Chinese Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, Chinese Journal of New Drugs and Chinese Journal of New Drugs and Clinical Remedies, all of which are core journals produced by Peking University.10

|

Table 3 Statistics of Journals Published About CRN with High Publication Volume in China |

Funding Support

Scientific research funding is an important indicator used to evaluate the academic quality and level of journals.11 Financial support for CRN research in China is as follows: among the literature included in this study, there were 42 funded papers, and the ratio of funded papers was 21.1% (funded papers ratio = number of funded papers/total papers x 100%), out of which 10 papers were at the national level (5.02%), 23 at the provincial level (11.56%) and seven at the institutional level (3.52%). These figures show the lack of financial support for CRN research in China.

Types of Literature

For the types of literature relating to CRN research in China, see Table 4.

|

Table 4 Types of Literature on CRN Published in China |

Hotspots in the Research Field

Research Hotspots Based on Keyword Frequency and Mediated Centrality

Authors use keywords to favourably summarise their core arguments; these keywords’ distribution frequency and characteristics reflect the general characteristics of the research field, the interconnection between research hotspots, and development trends. In this study, a keyword co-occurrence analysis was performed by CiteSpace software to generate a knowledge graph (Figure 2). The main idea of an intermediate centrality algorithm is to measure the extent to which a node is located in the middle of the shortest path between two other nodes, as a “traffic hub”. This paper counted the top 20 keywords (in terms of frequency and intermediary centrality) from 1992 to 2020; the keywords with the highest frequency were clinical trials, clinical research and CRNs.

|

Figure 2 Trend of annual number of documents on CrN in China from 1992 to 2020. |

Research Hotspots Based on a Keyword Clustering Analysis

A keyword clustering analysis was performed by CiteSpace software to generate a knowledge map (Figure 3). A keyword clustering knowledge map can classify hot keywords according to their scope and facilitate the identification of hot areas of research. The clustering analysis, combined with the keywords contained in the clustered content, provides further insight into the specific content of a given topic. There are two important indicators in the clustering view: the Q value of modularity, and silhouette values. The Q value of modularity is an indicator of network modularity evaluation; Q > 0.3 is generally considered to mean a significant clustering structure. The silhouette value is used to measure network homogeneity; here, S > 0.5 is generally considered reasonable, and S > 0.7 is considered convincing.12 The Q value of 0.791 and an S value of 0.949 in the automatic clustering label view generated by the software indicates that this study’s clustering results are highly credible.

|

Figure 3 Knowledge map of keyword co-occurrence in CrN research field in China. |

The keywords appearing in the literature on CRNs published in China from 1992 to 2020 can be roughly clustered into 10 major categories (Figure 3). These keywords are not completely independent of each other, with overlaps and crossovers. The analysis results based on the clustering were then summarised, and four specific research issues highlighted by different keywords were discussed.

The keywords in the first category concern clinical research (including drug clinical trials, GCP, clinical trials and new drugs); the literature within this cluster primarily focuses on the exploration and analysis of the roles, responsibilities and functions of CRNs at different stages and in different types of clinical trials. Keywords in the second category concern CRNs (including research nurses and clinical research coordinators [CRCs]). The literature within this cluster is mostly a reflection of the current status of CRN development in China and a discussion of the construction and practice aspects of CRN training models. Keywords in the third category concern influencing factors. The literature within this cluster focuses on the factors affecting the trial quality, effectiveness and level of CRNs in clinical trial implementations from different perspectives. Keywords in the fourth category concern management; the literature within this cluster includes studies on CRN management, with a focus on the training, assessment and promotion of CRNs. Analyses of CRNs’ management of trial quality, ward standardisation, and practice and effectiveness in clinical trials also exist. Most of the literature under this cluster was published in the last five years.

Trends Based on Keyword Emergence

Identifying and tracking research frontiers can provide researchers with the latest evolutionary developments in disciplinary research, allowing them to predict trends in research areas and identify issues that need further exploration. In CiteSpace, research frontiers are rising theoretical trends and emergent new topics that should be synthesised and judged based on an analysis of growing bodies of literature and terms.13 In this study, the 25 nodal emergent words with highly developing values were obtained by running the CiteSpace software (Figure 4); the top five keywords in terms of the strength of keyword emergence were new drugs (3.44), clinical research assistants (2.78), nursing staff (2.10), bioequivalence (2.06) and nurses (1.88).

|

Figure 4 Keyword clustering knowledge map in the literature on CrN published in China. |

|

Figure 5 Keyword emergence rate in CrN literature published in China (top 25). |

At the time when each keyword emerged, early-stage literature relating to CRNs and published in China was mostly about practical experience in clinical/new drug research (Figure 5). The middle stage mainly concerns discussions of CRNs’ capabilities in various aspects of clinical trials (such as the management of adverse reactions, drugs and standard operating procedures), which indicates that CRNs were becoming more involved in clinical trials and playing an increasing function and role in this area. The later published literature focuses more on clinical drug trials and on bioequivalence studies; as such, it pays more attention to the quality and level of trials, indicating that the level of clinical trials in China has reached a new high standard. Generally speaking, the keywords that have emerged to date can be regarded as forming the current research frontier in this field.14 The prevalence of the terms “clinical research nurse”, “bioequivalence” and “clinical research coordinator” highlighted in this study continues today. This indicates that cutting-edge topics in the clinical research nursing field in China are more concerned with the development of CRNs and CRCs than bioequiavailability.

Discussion

The Development of and Increasing Attention Paid to CRNs in China

CRNs first appeared in the US in the 1970s, in university-affiliated hospitals, large public hospitals and large research institutions. Such institutions are mainly served by research doctors, pharmacists, testers, nurses and other personnel with biomedical professional backgrounds. Nurses are the best choice for this role,15 which has been widely accepted and developed in Europe, the US and Japan because of CRNs’ great contribution to the quality and efficiency of clinical trials.16 Since the 1990s, there has been a global boom in clinical research, and the development of multinational and multicentre collaborative clinical studies has led to prosperous growth in the number of CRNs. In 2007, the US began to build a conceptual model of clinical research nursing practice areas and standardised and described the work of CRNs; thus, the education and training concepts and CRN management decision-making mechanisms are relatively mature.17 In addition, the definition, job content, inclusion and training standards for CRNs have been practised and explored to varying degrees in the UK, Japan, New Zealand and Italy.16,18,19

CRNs in China emerged around the 1990s, with a late start and slow development.20 This process can also be seen in the content of the literature published between 1992 and 2003, which mainly offers basic information about the working experience of foreign CRNs in the medical nursing branch. The earliest report regarding CRN practice in China was published during a clinical trial for a new Class Ι drug invented in China in 1999; this suggests that nurses played an essential role in ensuring the smooth conduct of the trial from a nursing perspective.21 In 2005, at the National Oncology Nursing Society’s academic exchange meeting with the Chinese Nursing Association, the term CRN was used for the first time, and the role and professional characteristics of CRNs in drug clinical trials were standardised.22 Since then, the exploration of the CRN role and the practice of clinical research nursing in China have entered a new stage. Since 2005, the number of articles on CRNs has increased significantly; issues of concern include the problems facing CRNs in clinical trials and the role CRNs play at various key points during trials. In addition, the literature introduces and reflects on domestic and foreign experiences and offers an in-depth discussion on the cultivation and management of CRNs in China. The role played by CRNs in China has gradually developed towards a move from part-time to full-time staff,2 who work at all levels within hospitals and who have national clinical trial qualifications.

An overview of the development of CRNs in China reveals that the number and quality of studies that focus on these nurses have increased significantly; this reflects how the status and role of CRNs in clinical trials are becoming more recognised, more valued and more likely to play an important role in guiding both the summary of the initial exploration work and the direction of future development. However, it is clear from the characteristics of the authors and institutions that are producing this literature that both the practices and exploration of CRNs in China are regionalised and unevenly influenced by various factors such as the level of urban development and health policy orientation. It is also apparent that the overall level of research still needs to be improved, with more exploratory and empirical articles published and less empirical research in line with China’s national conditions. Therefore, generally speaking, the development of CRNs in China is still in its initial stage, but both the attention paid to these nurses and their importance are increasing.

Clarifying the Role and Scope of Work: A Central Theme in CRN Development

Whether through keyword frequency statistics and mediated centrality or through the interpretation of keyword clustering and emergence, “clinical research”, “research nurse”, “drug clinical trial” and “management” are all hot words in the literature on CRNs that has been published in China. Through an analysis of these hot terms and of the literature where the keywords can be found, it becomes apparent that most of the studies are discussions of the professional orientation and job responsibilities of CRNs. This literature includes both references to the advanced experience of CRNs in foreign developed countries and a practical summary of localisation in China.

In fact, at the early stage of clinical drug trial development in China, CRNs and CRCs were not distinguished and were defined in general terms as staff members authorised by the principal investigator and trained to coordinate investigators in clinical research for non-medical matters of judgement.6,23 However, this definition does not reflect the importance of CRNs in ensuring the quality of clinical research and the safety of subjects; therefore the above perception of the role of CRNs is ambiguous and not conducive to their development.24 A clear professional orientation is essential if nurses are to actively participate in clinical practice, establish positive self-understanding and improve their professional identity, further enhancing the quality of care and their professional satisfaction.3,25–28 Clarifying the role and scope of work of CRNs is of great significance to the development of this professional field. The role’s orientation and functions and the practice areas for CRNs were all explored and studied by researchers from developed Western countries in the early 1990s.29

With the introduction and implementation of CRC industry guidelines in China, the occupational scope of CRNs and CRCs has been further defined; the occupational scope of CRNs is now more inclined towards protecting subjects and nursing operations related to clinical trials. Some domestic scholars3,30–33 have already investigated and practised CRN job categories that meet China’s national conditions and hospital development needs and have constructed an initial framework for CRN core job competencies. In addition, Consensus of experts on clinical research nurse management in China, released in June 2021, offers a detailed description of the definition, job settings and qualifications, duties and tasks, training and assessments, job quantifications and manpower allocation performance assessments and promotion of CRNs. This is a milestone on the road to the standardised development of CRNs in China and lays the foundation for its future standardised management and employment.

Specialisation: The Future Direction of CRN Development

In this study, the keywords related to CRNs in China that have a high emergence intensity are “new drug”, “nursing staff”, “clinical research assistant”, “bioequivalence” and “clinical research nurse”. “Bioequivalence” and “clinical research coordinator” continued to emerge so far, which indicates that nurses play an essential role in China’s clinical drug trials. This puts forward higher requirements for CRN practice and the exploration of the professional development of CRN positions, with considerations including position management, performance appraisal and promotion. The exploration of this field will offer a future research direction for the development of CRNs in China.

CRN nursing practice is focused on maintaining a balance between trial subject care and compliance with the study protocol.34 The CRN plays the role of educator, advocate, partner, data collector, direct caregiver, liaison, interpreter and observer in clinical trials; this is all very challenging and complex, requiring leadership and organisational skills.35 However, the above skills are beyond the scope of traditional specialty nursing, and there are no arrangements to teach them in China’s current nursing education system. Throughout the development of research nurses in Europe, the UK, Japan and other developed countries, the countries have established and continuously improved their education and training systems,36 not only by increasing the number of practical research training courses and the provision of internship opportunities in universities and colleges to develop practical nursing skills, but also through the provision of online training and continuing education courses in various institutions to improve students’ critical thinking skills. This approach will help CRNs better adapt to their roles and career development. Therefore, there is an urgent need for nursing institutions in China to construct relevant education and training programmes and courses based on the core competencies and developmental needs of CRNs.

The development of the profession cannot be separated from a sound management system for inclusion, training and assessment. A sound management system can include more excellent talents for the CRN team and bring ongoing vitality to the profession. With the flourishing development of clinical trials in China and the emergence of more full-time CRNs as an extension of the field of nursing specialties, questions arise as to how to select, train, employ and evaluate the management of CRNs, as well as how to adopt a reasonable incentive mechanism to bring the role of CRNs in nursing work and research into play. The field of practice for CRNs is unlike that of clinical wards, and there are differences between various specialties; thus, requirements for CRN core job competencies will vary. This situation urgently requires health administration departments and medical institutions to establish sound job inclusion criteria, evaluate CRN work and provide continuing education and performance appraisals. Improving the appraisals plays a crucial role in the career development of this profession.37,38

As an emerging professional nursing role, the development of the CRN role also requires the establishment of an academic community that can promote the sharing of research results and practical experience among peers both at home and abroad, so that the training, employment and management of CRNs can gradually move along a scientific and standardised path and contribute nursing power to the high-level development of clinical research in China.

In summary, the role of the CRN is currently in a period of rapid development; a single-core research pattern has been formed, with a strong leading role in the development of CRNs. In the future, cross-regional authors and inter-institutional cooperation need to be strengthened to narrow the regional development gap and to promote and popularise rigorous and standardised clinical nursing methods nationwide, thereby improving the quality of clinical nursing research results. In recent years, clinical nursing research has focused on clinical trials; however, the scope of this research needs to be expanded. It can begin with education and management designed to change the concept of clinical nurses’ experience-based care, strengthen the continuing education offered by clinical nursing courses and effectively improve the practical ability of CRNs to provide more scientific and high-quality nursing services to patients.

Conclusion

In China, the role of the CRN is currently in a period of rapid development. CRN research mainly involves single-centre studies and lacks financial support. In the future, it will be necessary to increase capital investment, strengthen cross-regional cooperation between researchers and institutions to narrow the regional development gap, and promote strict and standardised CRN training models and qualification certification to improve the quality of clinical nursing research.

Data Sharing Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, any relevant ethical issues are not involved.

Funding

There is no funding to report.

Disclosure

All of the authors had no any personal, financial, commercial, or academic conflicts of interest separately.

References

1. Liu N, Gao X, Wang Y, Guangli M. Bibliometric analysis on influencing factors of scientific research ability of nursing staff in China. Chin J Integr Nurs. 2019;5(9):25–29.

2. Kunhunny S, Salmon D. The evolving professional identity of the clinical research nurse: a qualitative exploration. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(23–24):5121–5132. PMID: 28859249. doi:10.1111/jocn.14055

3. Jones CT, Hastings C, Wilson LL. Research nurse manager perceptions about research activities performed by non-nurse clinical research coordinators. Nurs Outlook. 2015;63(4):474–483. PMID: 26081563. doi:10.1016/j.outlook.2015.02.002

4. Jackson M. Good financial practice and clinical research coordinator responsibilities. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2020;36(2):150999. PMID: 32253048. doi:10.1016/j.soncn.2020.150999

5. Liu X, Li D, Li Y, et al. Investigation on the work contents of clinical research nurses and clinical research coordinators. Chin J New Drug. 2019;28(03):325–331.

6. Yan Z, Min T, Yongchuan C, Peiyuan X. Discussion on the introduction of clinical research coordinator management model into drug clinical trial institutions. Chin J Clin Pharm. 2017;26(1):48–50. doi:10.19577/j.cnki.issn10074406.2017.01.012

7. Zhijuan L, Chen Y, Nana Z, Wanli L, Favor W. Analysis and countermeasures of nursing scientific research status of clinical nurses in China. Today Nurs. 2016;2016(9):145–147.

8. Bangyu Z, Li Y, Zhang P, Xu Y, Zhou B. Study on pressure source characteristics of Chinese clinical research coordinators. Chin J New Drug. 2020;29(15):1752–1756.

9. Rickard CM, Roberts BL. Commentary on Spilsbury K, Petherick E, Cullum N, Nelson A, Nixon J & Mason S (2008) The role and potential contribution of clinical research nurses to clinical trials. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17(19):2664–2666. PMID: 18808632. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02402.x

10. Wang XP. Comparative analysis of evaluation indexes of major academic journals in Qinghai universities. JS Sci Technol Inf. 2016;2016(23):16–20.

11. Carter EJ, Cato KD, Rivera RR, et al. Programmatic details and outcomes of an Academic-Practice Research Fellowship for clinical nurses. Appl Nurs Res. 2020;55:151296. PMID: 32507664. doi:10.1016/j.apnr.2020.151296

12. Li H, Wang TT. Hot topics and foreground evolution of international research on higher education for persons with disabilities-an econometric and visual analysis based on SSCI and SCI journal literature. J Teach Educ. 2018;5:527–536.

13. Ma A, Li Q, Guo SX, et al. Hot spots and frontiers of medical talent training research in China–a visual analysis based on CiteSpace. Clin Med Res Pract. 2019;4(28):194–196.

14. Guo L, Lu G, Tian J. A bibliometric analysis of cirrhosis nursing research on web of science. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2020;43(3):232–240. PMID: 32487955. doi:10.1097/SGA.0000000000000457

15. Bu QY, Xiong NN, Zou JD, et al. Important role of clinical trials: clinical research coordinator. Chin Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2004;4(1):1–9.

16. Bender M. Conceptualizing clinical nurse leader practice: an interpretive synthesis. J Nurs Manag. 2016;24(1):E23–31. PMID: 25655928. doi:10.1111/jonm.12285

17. Black L, Kulkarni D. Perspectives of oncology nursing and investigational pharmacy in oncology research. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2020;36(2):151004. PMID: 32265165. doi:10.1016/j.soncn.2020.151004

18. Mendes MA, da Cruz DA, Angelo M. Clinical role of the nurse: concept analysis. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24(3–4):318–331. PMID: 24479870. doi:10.1111/jocn.12545

19. Nibbelink CW, Brewer BB. Decision-making in nursing practice: an integrative literature review. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(5–6):917–928. PMID: 29098746; PMCID: PMC5867219. doi:10.1111/jocn.14151

20. Laurant M, van der Biezen M, Wijers N, et al. Nurses as substitutes for doctors in primary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;7(7):CD001271. PMID: 30011347; PMCID: PMC6367893. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001271.pub3

21. Zhou SX, Lu H, Fu YR. Care of new drugs in Phase I clinical tolerability trials. South J Nurs. 1999;4(2):20–21.

22. Gu WY. The role and professional characteristics of research nurses in drug clinical trials.

23. Courtenay M, Carey N, Burke J. Independent extended and supplementary nurse prescribing practice in the UK: a national questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007;44(7):1093–1101. PMID: 16750832. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.04.005

24. Tinkler L, Smith V, Yiannakou Y, et al. Professional identity and the clinical research nurse: a qualitative study exploring issues having an impact on participant recruitment in research. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74(2):318–328. PMID: 28792610. doi:10.1111/jan.13409

25. McCabe M, Cahill Lawrence CA. The clinical research nurse. Am J Nurs. 2007;107(9):13. PMID: 17721122. doi:10.1097/01.NAJ.0000287481.78601.38

26. Immonen K, Oikarainen A, Tomietto M, et al. Assessment of nursing students’ competence in clinical practice: a systematic review of reviews. Int J Nurs Stud. 2019;100:103414. PMID: 31655385. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103414

27. Taylor A, Staruchowicz L. The experience and effectiveness of nurse practitioners in orthopaedic settings: a comprehensive systematic review. JBI Libr Syst Rev. 2012;10(42 Suppl):1–22. PMID: 27820153. doi:10.11124/jbisrir-2012-249

28. Brooks Carthon JM, Hedgeland T, Brom H, et al. “You only have time for so much in 12 hours” unmet social needs of hospitalised patients: a qualitative study of acute care nurses. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28(19–20):3529–3537. PMID: 31162863; PMCID: PMC6739175. doi:10.1111/jocn.14944

29. Deng J, Liu YD, Li FF, et al. The enlightenment of the role of American clinical research nurse to China. Nurs Res. 2013;27(12):1143–1145.

30. Liu Y, Cao J, Liu G, et al. Exploring the role function and management model of research nurses. Chin Nurs Manag. 2016;16(2):266–269.

31. Pung J, Rienhoff O. Key components and IT assistance of participant management in clinical research: a scoping review. JAMIA Open. 2020;3(3):449–458. PMID: 33215078; PMCID: PMC7660951. doi:10.1093/jamiaopen/ooaa041

32. Guo Y, Wang X, Plummer V, et al. Influence of core competence on voice behavior of clinical nurses: a multicenter cross-sectional study. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2021;14:501–510. PMID: 33953622; PMCID: PMC8092618. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S309565

33. Kao CY, Huang GS, Dai YT, et al. [An investigation of the role responsibilities of clinical research nurses in conducting clinical trials]. Hu Li Za Zhi. 2015;62(3):30–40. Chinese. PMID: 26073954. doi:10.6224/JN.62.3.30

34. Hemingway B, Storey C. Role of the clinical research nurse in tissue viability. Nurs Stand. 2013;27(24):62, 64, 66–68. PMID: 23505898. doi:10.7748/ns2013.02.27.24.62.e7113

35. Labrague LJ, McEnroe-Petitte DM, Leocadio MC, et al. Stress and ways of coping among nurse managers: an integrative review. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(7–8):1346–1359. PMID: 29148110. doi:10.1111/jocn.14165

36. Shirey MR, McDaniel AM, Ebright PR, et al. Understanding nurse manager stress and work complexity: factors that make a difference. J Nurs Adm. 2010;40(2):82–91. PMID: 20124961. doi:10.1097/NNA.0b013e3181cb9f88

37. Liu XH, Lu YH, Ma XX, et al. Exploration and practice of clinical research nurse position management in a specialized oncology hospital. Chin Nurs Manag. 2021;21(2):284–287.

38. Huo P, Qiu H, Wang W, et al. The role and advantages of head nurses as clinical research coordinators. Chin J Mod Nurs. 2013;19(26):3258–3261.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.