Back to Journals » Advances in Medical Education and Practice » Volume 7

Use of intuition by critical care nurses: a phenomenological study

Authors Hassani P, Abdi A , Jalali R , Salari N

Received 11 November 2015

Accepted for publication 10 December 2015

Published 10 February 2016 Volume 2016:7 Pages 65—71

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S100324

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Md Anwarul Azim Majumder

Parkhide Hassani,1 Alireza Abdi,1 Rostam Jalali,2 Nader Salari3

1Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, 2Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, 3Department of Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran

Background: Intuition is defined as an irrational unconscious type of knowing. This concept was incorporated into nursing discipline for 3 decades, but nowadays its application is uncertain and ignored by educational institutions. Therefore, this study aimed to explore critical care nurses' understanding of the use of intuition in clinical practice.

Materials and methods: In a descriptive phenomenological study, 12 nurses employed in critical care units of the hospitals affiliated with Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, were recruited to a study using purposive, semistructured interviews, which were then written down verbatim. The data were managed by MaxQDA 10 software and analyzed as qualitative, with Colaizzi's seven-stage approach.

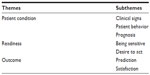

Results: Of the 12 nurses who participated in the study, seven (58.3%) were female and married, 88.3% (ten) had a Bachelor of Nursing (BSc) degree, and the means ± SD of age, job experience, and critical care experience were 36.66±7.01, 13.75±6.82, and 7.66±3.36 years, respectively. We extracted three main themes, namely “patient conditions”, “nurse readiness”, and “outcome”, and seven subthemes – including “clinical signs”, “patient behaviors”, “prognosis”, “being sensitive”, “desire to act”, “prediction”, and “satisfaction” – integral to understanding the use of intuition in clinical practice by critical care nurses.

Conclusion: The findings showed that some nurses were attracted by the patients’ conditions and were more intuitive about them, and following their intuition prepared the nurses to undertake more appropriate measures. The positive results that the majority of the nurses experienced convinced them to follow their intuitions more often.

Keywords: intuition, critical care nursing, qualitative research

Introduction

There are four ways of learning in nursing: empirical, aesthetic, personal, and ethical “knowing”.1,2 Intuition has been considered the “art of nursing” or “aesthetic knowing”, and “tacit knowledge” or “personal knowing”.3,4 Benner and Tanner theorized five steps to reach competence in clinical nursing, commencing with novice and continuing to expert. In this way, an expert nurse uses intuition for providing best-practice nursing care.5

Intuition has been defined as a feeling of knowing that something terrible is happening,6 an immediate unconscious perception,7 direct understanding of truths, independence of the analytical process,8 a nonlinear process of knowing through physical awareness, “emotional awareness” and “making connection between them”,9 and an irrational unconscious type of knowing. It has also been described as a “gut feeling” and with some negative connotations, such as “having a very bad feeling”, “feeling uncomfortable”, “feeling there was something terribly wrong”, “something missing”, or there was “something they had not done”.7,10

In a literature review, we found a few studies examining the use of intuition in nursing clinical practice. In this regard, Rew and Barrow stated that, “Intuition is a main component of decision-making and judgment in nursing”,11 while other studies mentioned the significant role of intuition in nursing ethics, which could be applied to choose the best moral act in a dilemma of a more complex clinical nature.12 Intuition has also been found to have a positive effect on reducing the mortality of patients,13 managing crises in unpredictable clinical conditions, and diagnosing the deterioration of patients.14,15

Although the entity of intuition has been verified by physiological studies,16,17 intuition is still considered an untrustworthy, unreliable concept in nursing and other allied health sciences where its application is unknown.18 Additionally, the belief that the legitimacy of intuition is affected by its complex, mysterious nature, and that it is somehow personal, has prevented its articulation by nurses in clinical practice.19 Due to its abstract nature and the inability of nurses to discuss its vagaries, intuition is still at the descriptive and qualitative stage in nursing.20 Ruth-Sahd maintained intuition recognition in nursing is constrained for many reasons, such as lack of a clear definition, lack of understanding of how nonrational ways of knowing complement the rational, failure to identify how the intuitive mind may inform evidence-based practice, lack of discourse about intuition in education, nurses’ reluctance to appear foolish or engender conflict if they cannot provide a rationale for their actions, self-perception of lack of intuitiveness, and fear that an intuitive action may be wrong.21

However, with respect to the aforementioned limitations and the lack of studies about the use of intuition by critical care nurses who are caring for more critically ill patients,22 the current study was conducted to explore the understanding of critical care nurses’ use of intuition in clinical practice.

Materials and methods

This qualitative study was done as descriptive phenomenology. As established by Edmund Husserl in the early 20th century, phenomenology is used to investigate the lived experiences of humans. The purpose of this approach is to assess the experiences of individuals as understood by them, without the researcher interpreting the meanings. Accordingly, the researchers must set aside all their prior knowledge about the issue.23 Intuition is an abstract concept and cannot be studied as objective; therefore, to investigate its essence, we must refer to the experiences of those who have used it.6

Participants

The participants were 12 nurses employed in critical care units of hospitals affiliated with Kermanshah University of Medical Science (KUMS), who were recruited using the purposive method. The inclusion criteria consisted of having worked in critical care units for at least 3 years, having experience of using intuition in clinical practice, and consent to participate in the study. The sample size was according to data saturation, with no appearance of new data during the interviews. Saturation in qualitative studies occurs during data gathering and analysis, when new information is not obtained, as verified by the scrutiny of at least two knowledgeable experts in qualitative research.24

Data collection

For data collection, permission was given by the officials of the research deputy of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (SBMU), KUMS, and the hospitals affiliated with KUMS. We were then referred to the critical care units of the hospitals, where after the topic and objectives of the study were explained and assurance of confidentiality and anonymity of personal information were given, written informed consent was obtained from the participants. In order to identify the most suitable participants, the researcher described two of his experiences about using intuition in clinical practice, which resulted in the enrollment of those nurses who had experienced it and who also met the inclusion criteria. A deep semistructured interview was conducted on the study participants, through a questionnaire with open questions, such as “What is the definition of intuition?” and “What are your experiences of using intuition in clinical practice?”, and some other probing questions, eg, querying where, why, and when. The duration of each interview was 30–60 minutes. The interviews were conducted in the critical care units during morning and evening shifts according to agreement between the researcher and the participants. This process lasted approximately 6 months: from March to August 2015. All the interviews were tape-recorded. MaxQDA 10 software was used for data management, and the data were analyzed as qualitative with the seven-stage approach of Colaizzi. The Colaizzi approach is applied for eliciting related concepts of lived human experiences and organizing the anecdotal data into phenomenology studies.25 For this purpose, the following steps were carried out. 1) After each interview, we listened to the audio files repeatedly, then transcribed them verbatim, after which the written files were read several times. 2) After reading the written interviews, we highlighted the meaningful related statements. 3) Concepts representative of each of the statements then emerged. 4) The researcher developed the concepts into categories based on their similarity. 5) The results were incorporated into larger categories. 6) We tried to offer a comprehensive description of the concepts. Finally, 7) the trustworthiness of the data was verified.

Trustworthiness

Rigor was achieved using several strategies included in the trustworthiness criteria described by Schwandt et al.7,26 To enhance credibility, the researchers conducted member checks with participants after the first-level analysis and again at several points during data analysis. Final member checking occurred as participants were asked to review the findings, comment on the accuracy of interpretations, and confirm descriptions. Credibility was also addressed through peer debriefing: the researchers shared the text summaries, identification of themes, constitutive processes, and final drafts of the findings with their colleagues knowledgeable in nursing and qualitative research. The participants varied in demographic characteristics, such as age, sex, work location, and experience in nursing and critical care units, and the researchers also believed in their philosophy of qualitative study, which increased the credibility. To support the study’s dependability, the researchers extensively studied texts with relevant themes, which were also scrutinized as external checks by experts in psychology and nursing and qualitative approaches. Themes extracted from the descriptions of the participants were tested and confirmed by suspension of the researchers’ prior ideas. The researchers submit that transferability of the findings is possible, because the sampling was purposive and informational redundancy was achieved. Also, the descriptions were assessed by three expert nurses apart from the study participants, producing results with sufficient congruence with their experiences to support transferability.

Results

Of the 12 nurses who participated in the study, seven (58.3%), were female and married, 88.3% (ten) had a Bachelor of Nursing (BSc) degree, and two had master’s (MSc) degrees. The mean ± SD of age, job experience, and critical care experience were 36.66±7.01, 13.75±6.82, and 7.66±3.36 years, respectively. These variable ranges were 28–50 years for age, 5–30 years for job experience, and 4–14 years for critical care experience. Nine of the nurses were working in intensive care units and three in cardiac care units. Qualitative analysis of the data revealed three themes and seven subthemes. The main themes were patient condition, nurse readiness, and outcome (Table 1).

| Table 1 Themes and subthemes in intuition use by critical care nurses in clinical practice |

Patient condition

Most of the nurses demonstrated that patient condition had little influence on the use of intuition, but from analyzing the data, we concluded they had expressed some common, similar statements about patients, which could be incorporated into the theme of patient condition and three subthemes: clinical signs, patient behavior, and prognosis.

Clinical signs

The majority of the participants described intuition as an understanding beyond and partly paradoxical to the clinical signs of patients. While some patients had normal vital signs, the nurses felt that they would deteriorate or death might occur. As interviewee 1 said about a 28-year-old male undergoing angioplasty operation: “The patient was clinically stable, the same as other patients of the unit […] and communicated with us about his family and job situations […] but I felt the patient would encounter a problem”. Some also believed, however, that the clinical situation of patients was very serious, but against their colleagues’ ideas the intuition informed them that patients’ conditions would improve. In this regard, interviewee 6 stated, “All the doctors had lost their hope in the patient […] additional to the brain aneurysm, she had severe edema and a liver problem; even the creatinine [blood creatinine] had been raised closed to dialysis [hemodialysis] […] but I was confident in doing my work, meaning I was sure that if I did something for the patient, she would be returned [would be recovered]”.

Patient behavior

Some nurses expressed their intuitions formed about younger patients or clients who attracted their attention. For example, interviewee 10 said, “[…] such as the patient in 10 bed. He was young, he was married, and had some children. I felt compassionate to him; my mind was constantly busy to him that why this happened to him (hospitalized in the intensive care unit) with these situations”.

Other participants stated when the patients’ behaviors changed, the intuition would come to them, and these changes were about the mood of the patients and their speech. Interviewee 11 displayed this: “The patients totally changed, in morality and somehow psychological turned, their sentences are also very interesting […] such as I have lasted my life, this was in the sentences of all who would be expired”. Some of the nurses were also affected by the good personality, communication, and morale of patients, but overall they revealed that intuition about special patients came to them involuntarily, with no identifiable logical reasons.

Prognosis

Nearly all the nurses indicated that their intuition inspired them to reassess the prognosis of the patients, which was not detectable by typical physical examinations and laboratory findings. In other words, some patients were in poor condition – in some cases, the physician had even ordered “no code” – but some participants, such as the nurse in interview 10, who cared for an old man with very low cardiac ejection fraction, understood the patient would survive. Alternatively, sometimes the patients were in good condition, while the nurse felt a bad prognosis was inevitable for them, as interviewee 5 stated about a 45-year-old patient: “His condition had no problem, the GCS [Glasgow Coma Scale] was 14, 15, the hemodynamic was stable, even we supposed the patient would be transferred to a general unit during the next 2 days, but I had an apprehension about him, I checked the patient, he had no problem […] [when] I was at rest, then my colleagues said he had had an instant bradycardia, and arrested, the CPR [cardiopulmonary resuscitation] was not successful; he died”.

Some participants foretold the prognosis of patients with confidence, as interviewee 6 declared about a young car-accident patient: “I told whether or not this patient will die, this patient will die surely; this was what my intuition said, it was not readable by the symptoms, the patient was stable, only there was a simple belly trauma, he went toward the radiology unit. Before reaching there, he was returned to the unit [he had died]”.

Readiness

Consequent to receiving the intuition, the nurses readied themselves for an appropriate response. In this regard, we elicited two subthemes: being sensitive and desire to act.

Being sensitive

After comprehending the intuition, the nurses paid more attention to particular patients by increasing their assessments and being more sensitive about them. The participant in interview 12 announced that due to intuition, her reactions to the patient were faster; she also said, “My attention span has developed”. On becoming more confident about a patient’s clinical status, some participants requested colleagues to do more physical examinations of their patient; they even called physicians to scrutinize and visit the patient without any compelling reason. Interviewee 9 mentioned, “Sometimes when a patient entered the unit, given my intuition signs, I told my colleague that the emergency trolley should be put beside the patient bed and the intubation (insertion of an endotracheal tube) devices readied, and please tell the resident (the resident physician) to visit this patient”.

Desire to act

The participants maintained that intuition encouraged them to perform a measure for recovery of the patient or predicted something unforeseen. Interviewee 6 stated, “I felt I must come back and remove his ‘trach’ [tracheostomy tube]. Likewise, when I came back, without changing clothes, directly I went to the bedside of the patient and did that work”. In a case where the CPR team had unsuccessfully finished their remedial actions, after a few minutes one of the nurses (interview 4) had an intuitive sense to inject adrenaline into the heart muscle of the dead patient without the physician’s order, after which he revived. The participant in interview 4 described his intuition: “This is a sense that forced me to fulfill that work”. Some of the participants expressed that sometimes the intuition would guide a last-ditch attempt to save patients. For instance, the participant in interview 9 remarked about a 40-year-female who had undergone heart surgery who survived after successful CPR, “If I was not sensitive to the patient (based on the intuition), without exaggeration, the patient would be dead”.

Outcome

The outcomes of critical care nurses’ use of intuition were shown in two subthemes: prediction and satisfaction.

Prediction

All the participants affirmed that their intuitions proved to be correct. The majority of them anticipated the patient’s death, with almost complete accuracy. Interviewee 3 stated about an old patient after cardiac surgery: “[My intuition] told me this patient will never awaken [wake up after general anesthesia]”. Some believed that intuition use had no negative results, because they took more care of their patients, and perhaps this care hindered the occurrence of intuitive predictions. Interviewee 8 stated that “Under 1 minute ago, I felt the patient would arrest […] if I had understood that 2 minutes later, the patient would have gone to other world [died]”. Nurses must still deal with some problems about the use of intuition when they predict an event about a patient. One of them is their lack of authority: they are limited in the medical interventions they can make without physician supervision to prevent patient deterioration, while some also believed that the intuition of nurses is denied by physicians. As interviewee 6 stated, “Unfortunately, the doctors don’t accept us [nurses]; they do not know more about intuition”.

Satisfaction

The nurses who experienced intuition and acted upon it were satisfied with their work and believed in the positive results of intuition. One of the nurses who acted on his intuition and whose patient recovered stated, “I cannot describe that happiness in that day, it is not comparable to anything, I thank God for this” (interview 9); and interview 2 (speaking about an old woman patient with thyroid cancer, who was supposed to go to a general unit by physician order and was hindered by the nurse, based on the latter’s intuition of her experiencing a cardiac arrest), mentioned, “I myself am very satisfied, for [based on my intuition] I didn’t allow that patient go to a general ward”. Some nurses explained that what happens based on intuition is really amazing and similar to a miracle, as interviewee 5 stated: “These people [intuitive nurses] can read God’s thoughts […] that is a miracle when a nurse sees a patient and thinks this patient will return”.

Discussion

This study aimed to explore the understanding of critical care nurses’ use of intuition. In this regard, the nurses indicated that patients’ particular conditions, such as inconsistency between prognosis signs and changing patient behaviors, and patients attracting nurses’ interest, fostered intuition. We found a lack of available research about patient conditions that induced intuition, because most of the research stressed the characteristics of the intuitive nurses. Ruth-Sahd and Tisdell showed that the length of time and the background situations that connect nurses to patients essentially affect the receipt of intuition. They also verified that when patients trust nurses, they tell the nurses more about their feelings and concerns, so the nurses can form spiritual relationships with patients and will be very relaxed with them. These patients were named “open patients”, because they wanted to be understood.10 Moreover, using the intuition is context-based, and accordingly Phelvin disclosed that nurses apply it to care for people with profound learning disability. This is done by “reading” the patients’ nonverbal cues.27 Smith et al concluded that nurses receive energy from their patients, which was mentioned in their study instrument by such statements as “I sense positive energy coming from my patient”, “I sense negative energy coming from my patient”, and “I sense an energy field around my patient”.9 This perhaps concurs with our results where nurses stated that the patient must have attracted their interest.

In the view of Green, some nurses saw the receipt of intuition as a major part of their role, whereas others experienced few intuitions for many reasons, including inadequate experience or conceptual knowledge, a lack of adequate clarity about the goal of their practice or of what is actually good for patients, or a lack of desire or commitment to achieving the best for their patients.28 Some patients also have valid intuitions about themselves that predict their prognosis and can be transferred to nurses via proper communication. In this regard, Buetow and Mintoft argued that the intuition of patients must be considered by clinicians for enhancing decision-making and planning their care.29 We believe that some nurses who are very serious about their patients’ conditions and are totally committed to their well-being can distinguish slight changes in the emotional and physical states of patients easily; therefore, they may achieve more intuition about them.

The findings revealed that intuition prepares nurses for dealing with unknown complications in patients, so that they are more sensitive to patients and want to act on signs and symptoms immediately. Complementary to our work, Lyneham et al categorized intuition in expert nurses into three stages, including the first stage (cognitive intuition), which is the consequence of a relationship between knowledge and experience, wherein nurses undertake many assessments without any evidence of rational processing of the intuition. However, in the transitional phase of embodied intuition, physical sensations and other behaviors enter into nurses’ awareness, encouraging them to trust their intuition fully and apply it easily without any doubts.30 Physicians also attempt to validate their intuitive thoughts with objective data by performing more physical and laboratory examinations.31 Facing the ontological, epistemological, and ethical conundrums, some researchers believe that intuition in medical sciences is mind–body dualism to provide an embodied cognition or knowledge needed for robust clinical reasoning. In their view, “Intuition, as an implicit and integral part of clinical reasoning, is associated with the way in which clinical judgment unties different elements such as deductive knowledge, information from observation, and past experience with groups of individuals, as well as statistical information”.32,33 Because of the contextual and affective factors that could affect its functioning, intuition is more vulnerable to errors than the analytic system, but Pelaccia et al realized the advantages of clinical reasoning and intuition to medical educators in consideration of the importance of providing learning environments in which medical students can develop their abilities to reason intuitively.34 Accordingly, some educational approaches are recommended in nursing for increasing intuition in students, such as mind-quietening exercises, journal writing, group brainstorming, sharing intuitive exemplars, preparing an atmosphere of curiosity with focusing on intuition, and asking students to assess the patients using intuitive feelings.35 Other emphasize the role of reflexivity, or reflective practice, in the development of intuitive professional knowledge and skills.34

It seems the assessment of patients could be prompted by doubts about the intuition “voice”; these doubts may be reduced by further experience in the application of intuition. Also, we believe this process starts with intuition awareness, and continues with analytic measures. Therefore, the closely intertwined relationship between these two issues could be considered a continuum, commencing with intuition and leading to more assessment.

Based on the results, the nurses were able to predict the situation of patients through their intuition, and were very satisfied after acting upon it. In accordance with our study, Lyneham et al concluded intuitive feelings can happen before the commencement of clinical signs in patients, enabling nurses to predict signs via intuition cues.6 Also, Smith et al demonstrated that when nurses know about a patient’s condition, they perform appropriate measures calmly and peacefully.9 The notion that nurses’ satisfaction from the successful application of their intuitive experiences to their work is perhaps related to their use of all necessary actions for the provision of best care of their patients requires more research.

Limitations

The participants were nurses who had experienced the effects of using intuition in clinical practice, and who purposely enrolled in the study. As qualitative research, these results could not be generalized to other locations. Therefore, qualitative studies in various clinical settings are recommended.

Conclusion

In this study, nurses felt intuitions about particular patients who had some personal and clinical characteristics. While the intuitions had many positive results for patients as well as nurses, the nurses were very comfortable using intuition, which they considered a lifesaver for patients. Following their intuition experiences, nurses paid more attention to the intended clients, and provided extra assessments and care of patients.

Although nurses and other health care workers repeatedly use intuition in clinical practice, we believe they have little information about it. However, as the first investigation of intuition in nursing in Iran, this study can now become a theoretical base for other research. We also believe educating nurses to use intuition may enhance the quality of patient care, but this proposal needs more qualitative and quantitative studies.

Acknowledgments

This study was taken from a PhD dissertation in nursing approved by SBMU, and the project was approved by the ethics committee of the research deputy of SBMU and KUMS. We are grateful for the cooperation of the officials of the Nursing and Midwifery School of SBMU, the research deputy and the affiliated hospitals of KUMS, and the nurses who participated in the study.

Author contributions

Because this study is part of a PhD dissertation, all the authors had an active role in the stages of the study included conception, design, data collection, data analysis, and interpretation of the data. The paper was written by PH and AA and revised by RJ and NS. The authors gave final approval of the version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Alligood MR. Nursing Theory: Utilization and Application. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2013. | |

Speziale HS, Streubert HJ, Carpenter DR. Qualitative Research in Nursing: Advancing the Humanistic Imperative. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2010. | |

Chaffey L, Unsworth CA, Fossey E. Relationship between intuition and emotional intelligence in occupational therapists in mental health practice. Am J Occup Ther. 2012;66(1):88–96. | |

Pearson H. Science and intuition: do both have a place in clinical decision making? Br J Nurs. 2013;22(4):212–215. | |

Benner P, Tanner C. Clinical judgment: how expert nurses use intuition. Am J Nurs. 1987;87(1):23–31. | |

Lyneham J, Parkinson C, Denholm C. Intuition in emergency nursing: a phenomenological study. Int J Nurs Pract. 2008;14(2):101–108. | |

Kosowski MM, Roberts VW. When protocols are not enough: intuitive decision making by novice nurse practitioners. J Holist Nurs. 2003;21(1):52–72. | |

McCutcheon HH, Pincombe J. Intuition: an important tool in the practice of nursing. J Adv Nurs. 2001;35(3):342–348. | |

Smith AJ, Thurkettle MA, dela Cruz FA. Use of intuition by nursing students: instrument development and testing. J Adv Nurs. 2004;47(6):614–622. | |

Ruth-Sahd LA, Tisdell EJ. The meaning and use of intuition in novice nurses: a phenomenological study. Adult Educ Q (Am Assoc Adult Contin Educ). 2007;57(2):115–140. | |

Rew L, Barrow EM. Intuition: a neglected hallmark of nursing knowledge. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 1987;10(1):49–62. | |

Sofaer B. Enhancing humanistic skills: an experiential approach to learning about ethical issues in health care. J Med Ethics. 1995;21(1):31–34. | |

Baird LM, Miller T. Factors influencing evidence-based practice for community nurses. Br J Community Nurs. 2015;20(5):233–242. | |

Odell M, Victor C, Oliver D. Nurses’ role in detecting deterioration in ward patients: systematic literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(10):1992–2006. | |

Rew L, Agor W, Emery MR, Harper SC. Intuitive skills in crisis management. Nursing connections. 2000;13(3):45–54. | |

Horr NK, Braun C, Volz KG. Feeling before knowing why: the role of the orbitofrontal cortex in intuitive judgments – an MEG study. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2014;14(4):1271–1285. | |

Spottiswoode SJ, May EC. Skin conductance prestimulus response: analyses, artifacts and a pilot study. J Sci Explor. 2003;17(4):617–641. | |

Woolley A, Kostopoulou O. Clinical intuition in family medicine: more than first impressions. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(1):60–66. | |

Smith A. Exploring the legitimacy of intuition as a form of nursing knowledge. Nurs Stand. 2009;23(40):35–40. | |

Rew L, Barrow EM Jr. State of the science: intuition in nursing, a generation of studying the phenomenon. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2007; 30(1):E15–E25. | |

Ruth-Sahd LA. What lies within: phenomenology and intuitive self-knowledge. Creat Nurs. 2014;20(1):21–29. | |

Hams SP. A gut feeling? Intuition and critical care nursing. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2000;16(5):310–318. | |

Gina M. Understanding the differences between Husserl’s (descriptive) and Heidegger’s (interpretive) phenomenological research. J Nurs Care. 2012:1(5):1–3. | |

Kerr C, Nixon A, Wild D. Assessing and demonstrating data saturation in qualitative inquiry supporting patient-reported outcomes research. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2010:10(13):269–281. | |

Shosha GA. Employment of Colaizzi’s strategy in descriptive phenomenology: a reflection of a researcher. Eur Sci J. 2012;8(27):31–43. | |

Schwandt TA, Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Judging interpretations: but is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New Dir Eval. 2007;2007(114):11–25. | |

Phelvin A. Getting the message: intuition and reflexivity in professional interpretations of non-verbal behaviours in people with profound learning disabilities. Br J Learn Disabil. 2013;41(1):31–37. | |

Green C. Nursing intuition: a valid form of knowledge. Nurs Philos. 2012;13(2):98–111. | |

Buetow SA, Mintoft B. When should patient intuition be taken seriously? J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(4):433–436. | |

Lyneham J, Parkinson C, Denholm C. Explicating Benner’s concept of expert practice: intuition in emergency nursing. J Adv Nurs. 2008;64(4):380–387. | |

Brien S, Dibb B, Burch A. The use of intuition in homeopathic clinical decision making: an interpretative phenomenological study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011;2011:935307. | |

Braude HD. Intuition in Medicine: A Philosophical Defense of Clinical Reasoning. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2012. | |

Marcum JA, Braude HD. Intuition in medicine: a philosophical defense of clinical reasoning. Theor Med Bioeth. 2014;35(5):401–405. | |

Pelaccia T, Tardif J, Triby E, Charlin B. An analysis of clinical reasoning through a recent and comprehensive approach: the dual-process theory. Med Educ Online. 2011;16:5890. | |

Smith A. Measuring the use of intuition by registered nurses in clinical practice. Nurs Stand. 2007;21(47):35–41. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.