Back to Journals » Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity » Volume 14

Use of Eye Care Service and Associated Factors Among Adult Diabetic Patients Attending at Diabetic Clinics in Two Referral Hospitals, Northeast Ethiopia

Authors Ahmed TM, Demilew KZ , Tegegn MT , Hussen MS

Received 16 March 2021

Accepted for publication 30 April 2021

Published 24 May 2021 Volume 2021:14 Pages 2325—2333

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/DMSO.S311274

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Ming-Hui Zou

Toyba Mohammed Ahmed,1 Ketemaw Zewdu Demilew,2 Melkamu Temeselew Tegegn,2 Mohammed Seid Hussen2

1School of Nursing and Midwifery, Wollo University, South Wollo, Dessie, Ethiopia; 2Department of Optometry, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Gondar, Gondar, Ethiopia

Correspondence: Melkamu Temeselew Tegegn

Department of Optometry, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Gondar, POB − 196, Gondar, Ethiopia

Tel +251947304125

Email [email protected]

Purpose: The objective of this study was to determine the proportion of use of eye care service and associated factors among adult diabetic patients attending diabetic clinics in two referral hospitals, Northeast Ethiopia, 2020.

Methods: A hospital-based cross-sectional study was carried out with a sample size of 546 at Dessie and Debre-Birhan Comprehensive Specialized Hospitals from July 06 to August 14/2020. Systematic random sampling with a sampling fraction of 2 was employed to select study participants at outpatient departments in diabetic clinics. A pre-tested structured questionnaire, checklist, and visual acuity chart were used to collect the data. The collected data were entered into EPI-data version 4.4 and analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25. Binary logistic regression was fitted to identify the possible factors associated with the outcome variable, and the strength of association was expressed using an adjusted odds ratio at a 95% confidence interval. Variables with p-values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results: A total of 531 adult patients with diabetes participated with a response rate of 97.3%. In this study, the proportion of use of eye care service within the past 1 year was 31.5% (95% CI: 27.5, 35.4). Age from 40 to 64 years (AOR=2.86, 95% CI; 1.43,5.70) and > 65 years (AOR=3.15, 95% CI: 1.32,7.50), duration of diabetes 6– 10 years (AOR=2.15, 95% CI: 1.26, 3.69) and > 11 years (AOR=2.93, 95% CI: 1.51, 5.69), presence of visual symptoms (AOR=3.12, 95% CI: 1.56, 6.18), good attitude on the need of a regular eye checkup (AOR=2.87, 95% CI: 1.68, 4.94), and good knowledge about diabetic ocular complication (AOR=2.29, 95% CI: 1.33, 3.94) were positively associated with the use of eye care service.

Conclusion: The proportion of use of eye care service among adult diabetic patients was low. The use of eye care service was significantly and independently associated with older age, longer duration of diabetes, presence of visual symptoms, good attitude on the need of a regular eye checkup, and good knowledge about diabetic ocular complication. We recommend that the patients with diabetes should be taught about diabetic ocular complications and the importance of regular eye check-ups by health professionals to increase utilization of eye care services by patients with diabetes.

Keywords: diabetes mellitus, use of eye care service, Northeast Ethiopia

Introduction

Globally in 2017, there was estimated 451 million people (aged between 20 and 79 years) were suffered from diabetes, and the number is expected to rise to 693 million by 2045. Moreover, in 2017, the projected national prevalence of diabetes in Ethiopia that estimated by the International Diabetes Federation was 5.2%.1

People with diabetes tend to have a higher risk of developing eye complications than those people without diabetes. This is because people with diabetes to have a persistently elevated blood glucose level can cause the development of serious eye complications, which leads to visual impairment.2 More than 35% of people with diabetes globally had developed diabetic retinopathy, of whom 10% of individuals lived with visual significant diabetic retinopathy.3

The prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in Africa was 31.6%,4 while the national prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in Ethiopia was 19.48%.5 Furthermore, a study done in Dessie Comprehensive specialized Hospital, Ethiopia showed that the prevalence of visual disturbances due to diabetes was 28.9%.6

Proper use of eye care services is important to reduce the burden of visual impairment due to diabetic ocular complications.7 Some of those diabetic eye complications are asymptomatic at their early stages for which they are left undiagnosed early.8 Many people living with diabetes particularly those living in low and middle-income countries tend to go to eye care services only when the eye condition becomes sight-threatening or when there is a sudden deterioration of vision.7

The American Academy of Ophthalmology recommended detailed eye examinations for people with diabetes within five years of diagnosis for type I diabetes and at the time of diagnosis for type II diabetes patients.9

The studies done in developed countries such as the United States of America, Europe and Turkey showed that the proportion of use of eye care service for people with diabetes ranges from 30 to 91.3%.10–13 On the other hand, the studies done in Asian countries revealed that the proportion of use of eye care service among people living with diabetes was between 15.3% and 67%.14–16 Despite the high prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in African including Ethiopia, a study reported that the overall use of eye care service for those people with diabetes in low-income countries was 18%.17

Furthermore, the studies conducted in Nigeria, and Kenya showed that the proportion of use of eye care services for those people with diabetes were 29% and 13.3%, respectively.18,19 Moreover, a study done in Ethiopia reported that utilization of eye care service among the older adult population was 23.8%.20

Most research done regarding the use of eye care services reported that lack of health insurance, absence of visual symptoms, poor knowledge about diabetic ocular complications, no need of screening at an asymptomatic stage, poor attitude towards the need for regular eye checkups, and lack of time were negative impacts on the use of eye care service.18,21,22

Diabetes-related visual impairment is not only a result of a large financial burden on individuals and their families due to the cost of treatments but also has a substantial economic impact on countries and national health systems. This is mainly because of the loss of productivity and the long-term support needed to overcome the problem. It may also result in discrimination and may limit social relationships.7 Diabetic eye complications could be prevented by keeping normal or close to normal levels of blood glucose, blood pressure, and cholesterol.9 But, the most important and most cost-effective component of diabetes care is regular eye checkups which help in the prevention, early detection, and timely intervention of diabetes-related visual impairment.7

However, there is a lack of evidence regarding the use of eye care services for those patients with diabetes in Ethiopia as well as in the study area. This study will provide useful evidence for responsible bodies to implement appropriate interventions. Therefore, the objective of this study was to assess the proportion of use of eye care service and associated factors among adult diabetic patients attending diabetic clinics in two referral hospitals, Northeast Ethiopia.

Methods and Materials

Study Design, Period, and Area

A hospital-based cross-sectional study was conducted on 531 adult diabetic patients at Dessie comprehensive Specialized Hospital (DCSH) and Debre Birhan comprehensive Specialized Hospital (DBCSH) from July 06 to August 14/2020. DCSH is found in Dessie town, South Wollo Zone of Amhara National Regional State which is located 401 km northeast of Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia, and 480 km from Bahir Dar, the capital of Amhara regional state. According to the DCSH health management information system, the hospital provides a comprehensive health-care service in South Wollo Zone for about eight million people. DBCSH is found in Debre-Birhan town, North Shoa Zone of Amhara National Regional State which is located 130 km northeast of Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia, and 695 km from Bahir Dar, the capital of Amhara regional state. According to the DBCSH health management information system, the hospital is providing comprehensive health-care services in North Shoa Zone for about three million people. Both hospitals provide comprehensive health-care services including diabetic disease follow-up and care clinics; serving more than 1200 diabetic patients per month. Integrated secondary eye care service is also available at both hospitals. In addition, 12km away from the Dessie Comprehensive Specialized Hospital there is also another secondary eye care center at Borumeda referral hospital. These three secondary eye care services provide the diagnosis and management of diabetic ocular complications. When tertiary eye care services are needed, the three secondary eye care centers refer their patients to Menelik II referral hospital which is located in Addis Ababa.

Study Population and Eligibility Criteria

All adult patients aged 18 years and above, with Type I or Types II diabetes diagnosed before ≥1 year and who visited the outpatient diabetic clinics of Dessie and Debre-Birhan Comprehensive Specialized Hospitals during the data collection period were eligible to participate in the study. However, patients who were diagnosed in less than 1-year duration, patients with the gestational type of diabetes, patients who were severely ill admitted to the inpatient department and patients with a mental health problem who are unable to answer the questionnaire were excluded from the study.

Sample Size Determination

The Sample Size for Objective One

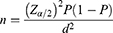

Previous evidence on the use of eye care services and associated factors among patients with diabetes in Ethiopia was limited. Therefore, 50% was used as the hypothesized proportion of use of eye care service among patients with diabetes to calculate the sample size. The single population proportion formula was used to determine the sample size with the following assumptions;

Where n – sample size, Z is Value of z statistic at 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.96, P – The hypothesized proportion of use of eye care service in Ethiopia = 50% because of had no similar previous study in Ethiopia 1-P = 1–0.50 = 0.50

d – Maximum allowable error (margin of error) 5% = 0.05 and the sample size was 384.16

The Sample Size for Objective Two

Duration of diabetes since diagnosis greater than or equal to 10 years was considered as the main consistent factors for the use of eye care service among patients with diabetes and used for sample size determination.21 So, the sample size for objective two was calculated by using EPI info version 7.2.2 software with the consideration of 80% of power, exposed to an unexposed ratio of 1:1, 95% of confidence level, percentage of unexposed as 66.8%, and percentage of exposed as 78.4%. The computer-generated sample size was 496. The sample size determined for objective two was used because it was large and adequate to meet both objectives. Finally, a 10% non-respondent rate was added to the calculated sample which gives a final planned sample size of 546.

Sampling Procedure

Based on the number of visiting patients, a proportional allocation of the desired sample was made between the two hospitals. The logbook of the hospitals showed that Dessie Comprehensive Specialized Hospital is visited by more than 700 patients with diabetes monthly whereas, Debre Birhan Comprehensive Specialized Hospital is visited by more than 500 diabetic patients. By taking these statistics and proportionally allocating the sample size, 314 samples were collected from Dessie Comprehensive Specialized Hospital and 225 samples were collected from Debre-Birhan comprehensive specialized hospital.

A systematic random sampling technique was used to select the study participants from all patients who were eligible for the study. The study subjects were selected with an interval of two from the first study participant and the first study participant was selected by lottery method in every data collection day.

Operational Definitions

Use of Eye Care Service

Visiting an eye care center for an eye examination or procedure (except due to injury) after the diagnosis of diabetes at least once in the last one year before the data collection time was considered as utilized, otherwise, not utilized.9 The presence of hypertension and/or dyslipidemia in the study participant was considered as systemic co-morbidity, which were assigned to the participants based on their medical folder. Participants with an age of >18 years were considered as adults.23 The age of the study participants was categorized into 18–39 years, 40–64 years, and ≥65 years.24

Visual impairment was defined based on the World Health Organization’s revised definition of visual impairment; visual impairment was defined as a presenting visual acuity of less than or equal to 6/18 in the better eye.25 The occupational status was classified as a farmer, housewife, unemployed includes individuals who had no job at time data collection and students, merchant, non-governmental employee, governmental employee, and others (daily labor and retired).

Data Collection Procedure and Quality Control

A total of six optometrists have participated in the data collection. Data were collected by using the Amharic version of the pre-tested and structured questionnaire, which was translated from the English version by consulting a language expert. The questionnaire regarding socio-demographic and economic data, knowledge, attitude, and practices-related questions were collected by face-to-face interview and clinical data such as type of diabetes, duration of diabetes, glycemic control, systemic comorbidities (hypertension and/or dyslipidemia) were collected through the checklist from the patients’ medical folders.

The knowledge and attitude-related questionnaire was adapted from previous studies.26–28 The knowledge of participants was assessed by using 16 questions. The value given for each question was 1 for those correctly answered and 0 for those answered wrong. The sum score ranges from 0 to 16 points. The overall knowledge of study participants regarding diabetic ocular complications was labeled as good or poor using median score value as a cutoff point. Participants who score greater than the median value were considered as having good knowledge and those who scored less than or equal to the median value were considered as having poor knowledge.

Also, the attitude towards the need for regular eye checkups for diabetic patients was assessed using a 5-point Likert scale which had eight questions, and the score points varied from 8–40 points. Therefore, when the score was greater than the median value, the overall attitude was categorized as a good attitude while the score was less than the median value, the overall attitude was categorized as poor.

The presenting visual acuity of the study participant was measured by using a portable tumbling E Optotypes Snellen chart with optimal illumination. Data quality was ensured through pre-testing the questioner on 5% of the sample at Woldiya General Hospital before the actual data collection period and training was given for the data collectors by the principal investigator. Besides, each day during the data collection 5% of the data was cross-checked for completeness.

Data Processing and Analysis

The data was coded and entered into EPI-Data version 4.4 software and then exported into Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25 for analysis. The descriptive statistics were summarized using frequency distribution and measures of central tendency. A binary logistic regression model was fitted to identify the possible factors associated with the outcome variable and the strength of association between the dependent and independent variable was expressed using an adjusted odds ratio with a 95% confidence interval. Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness of fit was used to check for model fitness. In multivariable binary logistic regression analysis, variables with a p-value of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted as per the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Gondar, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, School of Medicine, Ethical Review Committee. Verbal informed consent was approved by the ethical review committee. Furthermore, administrative permission letters were also obtained from Dessie and Debre-Birhan Comprehensive Specialized Hospitals to conduct the data collection. After a full explanation of the purpose of the study, verbal informed consent was obtained from each study participant. The right of discontinuing or refuse to participate in the study was informed for all study subjects. Confidentiality was assured by coding and locking the data and avoids any personal identifier. Participants who were visually impaired and at the risk of developing diabetic ocular complications were linked to the ophthalmic clinics after an adequate explanation was given about the need for an eye checkup.

Results

Socio-Demographic and Economic Characteristics

A total of 531 adult patients with diabetes participated in this study with a response rate of 97.3%. The median age of the study participants was 46 ± 25 years (IQR=25). Among the study participants, 272 (51.2%) were females and 369 (69.5%) were married. Out of the total study participant, 338 (63.7%) were urban dwellers and 366 (68.9%) did not have health insurance (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Study Participants Attending at Diabetic Clinics in Dessie and Debre Birhan Comprehensive Specialized Hospitals, Northeast Ethiopia (n=531) |

Clinical Characteristics of the Respondents

From the total study participants, 378 (71.3%) were Type-II diabetes, 228 (42.9%) had presented with visual symptoms, and 217 (40.9%) had systemic co-morbidities. Out of 531 study participants, 205 (38.6%) of them were presented with visual impairment. In contrast, more than half the study participants had poor knowledge about diabetic ocular complications (Table 2).

|

Table 2 Clinical Characteristics of Study Participants Attending Diabetic Clinics in Dessie and Debre-Birhan Comprehensive Specialized Hospitals, Northeast Ethiopia, 2020 (n=531) |

The Proportion of Use of Eye Care Service Among Study Participants

Out of the total study participant, 263 (49.5%) of study participants had a history of eye examination. In this study, the proportion of use of eye care services within the past 1 year among adult patients with diabetes was 31.5% (95% CI: 27.5, 35.4).

Among the total study participant, 68.5% of participants did not use an eye care service within the past 1 year. Of those participants, more than three-fourth (76.50%) of participants have not used an eye care service because those participants believed that no need for eye examination their vision is good (Table 3).

|

Table 3 The Reasons for Not Using Eye Care Services Among Adult Diabetic Patients Within the Past 1 Year, Northwest Ethiopia (n=268) |

Factors Associated with Use of Eye Care Service

By applying bivariable analysis, age, residence, occupation, knowledge about diabetic ocular complication, attitude towards the need for a regular eye checkup, duration of diabetes since diagnosis, presence of visual symptoms, presenting vision in the better eye, and presence of systemic co-morbidities were associated with the use of eye care service. However, in multivariable binary logistic regression analysis, age, knowledge, attitude, duration of diabetes, and visual symptoms remained significantly associated with the use of eye care service.

In this study, the odds of using an eye care service in those participants aged from 40 to 64 were 2.86 times (AOR=2.86, 95% CI: 1.43, 5.70) and in those participants aged ≥65 was 3.15 times (AOR=3.15, 95% CI: 1.32, 7.50) than those aged from 18–39 years. Those participants who had good knowledge about diabetic ocular complications had 2.29 times more likely to use eye care service than those participants having poor knowledge (AOR = 2.29, 95% CI: 1.33, 3.94).

As compared with a poor attitude towards the need for a regular eye checkup, those participants having a good attitude towards the need for regular eye checkup had 2.87 times more likely to use eye care service (AOR =2.87, 95% CI: 1.68, 4.92). The odds of use of eye care service for those participants with a duration of diabetes since diagnosis 6–10 years were 2.15 times (AOR= 2.15, 95% CI: 1.26, 3.69) and for those from ≥11 years was also 2.93 times (AOR=2.93, 95% CI: 1.51, 5.69) more than those with a duration of ≤5 years. Those participants who had visual symptoms were nearly 3 times more likely to use eye care service than their counterparts (AOR= 3.12, 95% CI: 1.56, 6.18) (Table 4).

Discussion

Diabetes mellitus can cause vision-threatening complications even without having visual symptoms and it requires proper eye care service utilization. This study was aimed to determine the proportion of use of eye care service and associated factors among adult diabetic patients attending diabetic clinics in two referral hospitals, Northeast Ethiopia.

The proportion of use of eye care service in this study within the past 1 year was 31.5% (95% CI: 27.5, 35.4). This finding is in line with the finding from studies done in Nigeria (29%),18 Tanzania (29%),29 USA (33.2%),24 and China (33.3%).15 However, the current study finding is higher than reports from studies have done in Ethiopia (23.8%),20 Kenya (13.3%),19 and Indonesia (15.3%).16 This difference might be the result of variation in inclusion and exclusion criteria of the studies, study setting, and sample size. For instance, the study done in Indonesia did not include those patients with diabetes who had eye examinations for glasses, on the contrary, this study included all adult diabetic patients with/without systemic co-morbidly who used eye care service for any examination and/or procedure except due to injury.

On the other hand, the result of this study is lower than reports from studies done in the USA (72.2%),10 Canada (72%),21 Switzerland (70.5%),11 Germany (56%),12 and Turkey (77.3%).13 This discrepancy might be due to variations in socio-demographic and socio-economic characteristics of the study population. The studies done in the USA and Germany were done in the older population. This leads to overestimating the result since ocular diseases are more prone to occur in an old diabetic patient. Besides, 65.9% of study participants in Canada had college and above educational level and 97.8% of participants in Germany had health insurance which could increase the use of eye care service.

In this study, increasing age was one of the important factors for use of eye care service, in which aged 65 and above was 3.15 times more likely to use eye care service than age from 18–39 years. This finding is supported by studies done in Ethiopia,20 South Africa,30 and the USA.24 The possible reason is that as the age increases, seeking eye care services could also increase because age-related eye diseases such as glaucoma, cataract, and diabetic retinopathy are more prevalent in old diabetic patients.31

Those participants who have good knowledge about diabetic ocular complication was 2.29 times more likely to use of eye care service than those who have poor knowledge. This finding is in line with reports from studies conducted in Kenya,19 Turkey,13 China,15 and Indonesia.16 Similarly, participants who had a good attitude towards the need for regular eye checkup was 2.87 times more likely to use of eye care services than those with a poor attitude. The possible reason for this might be because having good knowledge regarding the ocular effect of diabetes and a good attitude towards regular eye checkups may increase eye care-seeking behavior.

In this study, duration of diabetes since diagnosis was another most important factor to use of eye care service. Those participants who had DM for >11 years were 2.93 times more likely to use eye care services than those who had DM for <5 years. This result is consistent with the result of the studies done in Nigeria,18 South Africa,30 Indonesia,16 Germany,12 Turkey,13 and Canada.21 The possible reason is that the longer the duration of diabetes is the higher the occurrence of diabetic ocular complications such as diabetic retinopathy, which might increase utilization of eve care services.32 Besides, as the duration of diabetes increases, the physicians at the diabetic clinic may push them for ocular examinations.

Those participants who had visual symptoms were nearly 3.12 times more likely to use eye care service than their counterparts in this study. A similar finding was reported in a study done in the USA.10 The reason for this might be those individuals who had visual symptoms might utilize eye care services for the alleviation of their visual symptoms.

The limitations of the study are that the data collection includes self-reports from study participants which may affect the precision of the data as a result of recall bias or social desirability bias.

Conclusion

The proportion of use of eye care service among adult diabetic patients in this study was low. Use of eye care service was significantly and independently associated with older age, longer duration of diabetes, presence of visual symptoms, good attitude towards the need for a regular eye checkup, and good knowledge about diabetic ocular complication. We recommend that the patients with diabetes should be taught about diabetic ocular complications and the importance of regular eye check-ups by health professionals to increase utilization of eye care services by patients with diabetes.

Data Sharing Statement

All the necessary data are included in the manuscript, and if needed, the supporting data are available on request to the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the University of Gondar and Wollo University for financial support. The authors would also like to acknowledge study participants for their participation in the study.

Funding

There is no funding provided for this research work.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest for this research work.

References

1. Cho N, Shaw J, Karuranga S, et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;138:271–281. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2018.02.023

2. International Diabetes Federation. IDF DIABETES ATLAS.

3. Yau JW, Rogers SL, Kawasaki R, et al. Global prevalence and major risk factors of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(3):556–564. doi:10.2337/dc11-1909

4. Burgess P, MacCormick I, Harding S, et al. Epidemiology of diabetic retinopathy and maculopathy in Africa: a systematic review. Diabet Med. 2013;30(4):399–412. doi:10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03756.x

5. Fite RO, Lake EA, Hanfore LK. Diabetic retinopathy in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2019;13(3):1885–1891. doi:10.1016/j.dsx.2019.04.016

6. Abejew AA, Belay AZ, Kerie MW. Diabetic complications among adult diabetic patients of a tertiary hospital in northeast Ethiopia. Advances in Public Health. 2015;2015:1–7. doi:10.1155/2015/290920

7. International Diabetes Federation. IDF DIABETES ATLAS.

8. Wong TY, Sun J, Kawasaki R, et al. Guidelines on diabetic eye care: the international council of ophthalmology recommendations for screening, follow-up, referral, and treatment based on resource settings. Ophthalmol. 2018;125(10):1608–1622. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.04.007

9. Flaxel CJ, Adelman RA, Bailey ST, et al. Diabetic Retinopathy Preferred Practice Pattern®. Ophthalmology. 2020;127(1):P66–p145.

10. Ehrlich JR, Ndukwe T, Solway E, et al. Self-reported Eye Care Use Among US Adults Aged 50 to 80 Years. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137(9):1061–1066. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2019.1927

11. Konstantinidis L, Carron T, de Ancos E, et al. Awareness and practices regarding eye diseases among patients with diabetes: a cross sectional analysis of the CoDiab-VD cohort. BMC Endocr Disord. 2017;17(1):56. doi:10.1186/s12902-017-0206-2

12. Baumeister SE, Schomerus G, Andersen RM, et al. Trends of barriers to eye care among adults with diagnosed diabetes in Germany, 1997–2012. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;25(10):906–915. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2015.07.003

13. Cetin EN, Zencir M, Fenkçi S, et al. Assessment of awareness of diabetic retinopathy and utilization of eye care services among Turkish diabetic patients. Prim Care Diabetes. 2013;7(4):297–302. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2013.04.002

14. Sreenivas K, Kamath YS, Mathew NR, Pattanshetty S. A study of eye care service utilization among diabetic patients visiting a tertiary care hospital in Coastal Karnataka, southern India. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries. 2019;39(1):24–28. doi:10.1007/s13410-018-0617-2

15. Wang D, Ding X, He M, et al. Use of eye care services among diabetic patients in urban and rural China. Ophthalmol. 2010;117(9):1755–1762. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.01.019

16. Adriono G, Wang D, Octavianus C, Congdon N. Use of eye care services among diabetic patients in urban Indonesia. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129(7):930–935. doi:10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.147

17. Vela C, Samson E, Zunzunegui MV, et al. Eye care utilization by older adults in low, middle, and high income countries. BMC Ophthalmol. 2012;12(1):1–7. doi:10.1186/1471-2415-12-5

18. Onakpoya OH, Adeoye AO, Kolawole BA. Determinants of previous dilated eye examination among type II diabetics in Southwestern Nigeria. Eur J Intern Med. 2010;21(3):176–179. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2010.01.009

19. Mwangi N, Macleod D, Gichuhi S, et al. Predictors of uptake of eye examination in people living with diabetes mellitus in three counties of Kenya. Trop Med Health. 2017;45(1):1–10. doi:10.1186/s41182-017-0080-7

20. Morka ED, Yibekal BT, Tegegne MM. Eye care service utilization and associated factors among older adults in Hawassa city, South Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0231616. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0231616

21. Hwang J, Rudnisky C, Bowen S, Johnson JA. Socioeconomic factors associated with visual impairment and ophthalmic care utilization in patients with type II diabetes. Can J Ophthalmol. 2015;50(2):119–126. doi:10.1016/j.jcjo.2014.11.014

22. Piyasena MMPN, Murthy GVS, Yip JL, et al. Systematic review on barriers and enablers for access to diabetic retinopathy screening services in different income settings. PLoS One. 2019;14(4):e0198979. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0198979

23. World Health Organization. Considerations Regarding Consent in Vaccinating Children and Adolescents Between 6 and 17 Years Old. World Health Organization; 2014.

24. Maclennan PA. Eye care use among a high-risk diabetic population seen in a public hospital’s clinics. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(2):162–167. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.6046

25. World Health Organization. Blindness and vision impairment 2019; 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/blindness-and-visual-impairment.

26. Srinivasan NK, John D, Rebekah G, Kujur ES, Paul P, John SS. Diabetes and diabetic retinopathy: knowledge, attitude, practice (KAP) among diabetic patients in a tertiary eye care centre. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11(7):NC01–NC07. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2017/27027.10174

27. Drinkwater JJ, Chen FK, Davis WA, Davis TM. Knowledge of ocular complications of diabetes in community-based people with type 2 diabetes: the Fremantle Diabetes Study II. Prim Care Diabetes. 2021. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2021.01.008

28. Al Zarea BK. Knowledge, attitude and practice of diabetic retinopathy amongst the diabetic patients of AlJouf and Hail Province of Saudi Arabia. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10(5):NC05–8. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2016/19568.7862

29. Mumba M, Hall A, Lewallen S. Compliance with eye screening examinations among diabetic patients at a Tanzanian referral hospital. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2007;14(5):306–310. doi:10.1080/09286580701272079

30. Akufo KO, Asare AK, Sewpau R. Eye care utilization among diabetics in the South African National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (SANHANES-1): a cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2020;13:407. doi:10.1186/s13104-020-05245-5

31. Massin P, Kaloustian E. The elderly diabetic’s eyes. Diabetes Metab. 2007;33:54–59. doi:10.1016/S1262-3636(07)80052-8

32. Ting DSW, Cheung GCM, Wong TY. Diabetic retinopathy: global prevalence, major risk factors, screening practices and public health challenges: a review. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016;44(4):260–277. doi:10.1111/ceo.12696

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.