Back to Journals » Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare » Volume 14

Turnover Intention and Its Associated Factors Among Health Extension Workers in Illubabora Zone, South West Ethiopia

Authors Kitila KM , Wodajo DA, Debela TF , Ereso BM

Received 18 February 2021

Accepted for publication 4 June 2021

Published 28 June 2021 Volume 2021:14 Pages 1609—1621

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S306959

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Keno Melkamu Kitila,1 Dereje Alemayehu Wodajo,2 Tilahun Fufa Debela,3 Berhane Megerssa Ereso3

1College of Health Science, Mettu University, Mettu, Ethiopia; 2College of Health Science, School of Public Health, Mizan Tepi University, Mizan Aman, Ethiopia; 3Institute of Health, Faculty of Public Health, Department of Health Management and Policy, Jimma University, Jimma, Ethiopia

Correspondence: Keno Melkamu Kitila

College of Health Science, Mettu University, Mettu, Ethiopia

Email [email protected]

Background: The efficiency and quality of a health service can be compromised by turnover intention. Employees who intend to leave their job may identify themselves in the form of withdrawal, being predisposed to lateness, absenteeism, and declining participation. This study aimed to determine the level of turnover intention and to identify factors associated with turnover intention among health extension workers in the Illubabora zone.

Methods: A facility-based cross-sectional study with quantitative and qualitative methods of data collection was conducted on 125 randomly selected health posts. All health extension workers in the sampled health posts (n = 245) and 6 key informants were included from February 21 to April 20, 2020. Multiple linear regression models were used to indicate the association between dependent and independent variables. The data obtained from the in-depth interviews were coded, categorized then thematized manually, and supplemented with quantitative data.

Results: The prevalence of turnover intention of health extension workers was 52%. The turnover intention was highest among service length > 10 years (34.4%), level IV educational status (30.5%), married health extension workers (61.7%), and age category 26– 30 years (40.6%). Statistically significant variables were motivation (β=− 2.801; 95% CI − 5.097, to − 0.505), high workload (β=− 3.35; 95% CI − 6.038, to − 0.661) and career structure (β=− 3.452; 95% CI − 6.267, to − 0.638).

Conclusion: Overall, the magnitude of health extension workers’ turnover intention of their current job was high. Among variables, high workload, lack of motivation, and limited career structure were a significant predictor of turnover intention. Therefore, an amendment of the career structure and overtime payment should be made to retain health extension workers. They should be encouraged to perform only health sector tasks. Providing transportation is another important mechanism to reduce the workload.

Keywords: health extension workers, turnover intention, turnover, Ethiopia

Introduction

Health extension programs are embedded in societies, rendering preventive services for communities. Besides community prevention services, the Health Extension Package also provides health post-based basic services, including preventive health services such as immunization, family planning and curative health services such as first aid and treatment of malaria and intestinal parasites. Case referral to a health center is also provided when more complicated care is needed.1

In Health Sector Development Program II, the Ethiopian Federal Ministry (FMOH) aimed to achieve the Accelerated Expansion of Primary health care Coverage, through a Health Extension Package.2 The majority of Health Extension Workers (HEWs) were 10th grade complete and had an additional one-year training on 16 Health Extension Packages that are implemented in four areas of care. At the end of the Health Sector Development Program II, HEP Evaluation Study, the monthly salary has a slight variation from region to region ranging between Birr 530 (about USD 45) and 760 (about USD 63) with the majority getting Birr 670 (about USD 56).3 Evidence from the Oromia region showed that among HEWs deployed in the period of Health Sector Development Program II and III, 7.2% left their job.4

The government of Ethiopia has made great efforts to improve HEWs’ knowledge gaps and competency through in-service training and upgrading to level 4 (diploma), allowing the transfer of HEWs, which was impossible at the start, and a new salary structure was created following their level of training.5 Despite these efforts, a qualitative study done in 2015 in Bale Zone indicated some community health workers left their jobs totally.6

Turnover, a behavior of completely leaving, represents a significant cost in work force management and maintenance of the current labor force.7 The first negative results of worker turnover are the doubtlessly high cost related with replacing a departed employee.8 The costs associated with recruiting, selecting, and training new employees are always very high,9 so companies always want to increase their professional employees’ commitment and their knowledgeable employees’ retention. The second impactful negative effects of employee turnover are the disruption of organizational function, such as decreased performance and unfulfilled daily function.10

Turnover has been predicted by turnover intention in former studies.11 Intention to leave refers to an employee’s expressed intention of leaving their current job in the near future,12 which is meaningful, because it somewhat reflects the nature of the employers’ organizational management.13,14 Employees who consider quitting their current job decline participation in a job, manifesting their intention with lateness, absenteeism, avoidance behavior, and lowered performance with a low commitment level. Also, turnover intention negatively affects the quality of the work carried out.15

It is known that workers’ turnover intention can be highly costly for an organization; thus, minimizing worker turnover intention is crucial for human resource personnel and managers. Based on literature review, workforce shortages are not only due to the production of health professionals; they are influenced by various factors, such as attraction towards better salary, improved financial benefit, good educational opportunity, professional development opportunities, separation from spouse and children, personal health problems, workplace rules and regulation, inadequate resources for work, organization location and comfortable working conditions. Based on practicability the study focused on some variables categorized into personal, push and pull factors.16

In Ethiopia, turnover intention studies have now been conducted on different categories of health workers, such as nurses, midwives, laboratories, health officers, pharmacy, environmental health, and general practitioners.17–22 Similar studies were conducted specifically on nurses.23–25 In addition turnover intention of anesthesia professionals was also conducted.26 To the best of our knowledge, there has been no research conducted on health extension workers in the study area, and it is rare at the country level. So, this study would help elucidate the specific needs of health extension workers in particular contexts and inform the design of more effective HRH interventions.

In 2015, the Ethiopia Health Transformation Plan indicated that equity in healthcare delivery and guaranteeing the availability of health care to all is the first among the four agendas.5 This could be delivered when Health Extension Workers are committed and stable in their workplace. Therefore, this study aimed to determine magnitude of turnover intention and to identify factors associated with turnover intention among HEWs in the Illubabora zone. The study findings will be used by different levels of government to develop effective human resource management strategies that will reduce HEWs’ turnover rate.

Materials and Methods

Study Setting and Period

The study was conducted from February 21 to April 20, 2020, in the Illubabora Zone, Southwest Ethiopia. Illubabora is one of the zones in the Oromia Region in Ethiopia and is located about 600 kilometers from Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. It is bordered on the North by East Wollega zone and Benishangul-Gumuz region, on the east by Jimma Zone, on the south by South nations, Nationalities, and Peoples Region, and on the west by Kelem Wollega Zone. In 2020, the Illubabora Zone had a total of 13 districts and one town administration. It had two hospitals (one general and one district hospital), 519 rural health extension workers, and 260 rural health posts.

Study Design

Facility-based cross-sectional study designs with quantitative and qualitative data were employed.

Population

Source population

The source population was all Health Extension Workers who have been working in rural health posts of Illubabora Zone, Ethiopia.

Study Population and Recruitment Criteria

The study population for quantitative data was all Health Extension Workers who have been working in sampled rural health posts of Illubabora Zone. Health extension workers who had at least 6-month work experience were included in the quantitative strand of the study. Health extension cadres, who act as health post managers, were included for a qualitative strand of the study. Health extension workers who were not found during the data collection period due to annual leave, maternity leave, or due to some other social problems were excluded.

Sample Size Determination and Sampling Procedure

Out of 260, a random selection of 125 health posts was made, which was 48% of the health posts in the zone. The health posts randomly selected from the zone list were identified from six districts in the zone. They were Mettu, Alee, Hurumu, Bure, Bacho, and Yayo districts. All Health Extension Workers in sampled health posts who fulfilled the eligibility criteria (245) were included in the study because the Health Extension Workers in a single health post are less than four in number. Six Health Extension Cadres who had the most work experience were included purposely in the qualitative strand of the study since they could provide detailed information.

Study Variables

Dependent variable: Turnover intention

Independent variables

Socio-demographic variables: Age, marital status, educational status, service years.

Personal factors: Departure from spouse and children, personal health problem, lack of infrastructure for children’s education, family members’ related problem, unable to follow workplace rules and regulation, working as a HEW is a difficult job, friends/relatives changing job, an expectation not fulfilled from present job.

Push factors: Low salary, a high workload in the current workplace, limited/no career development opportunity, poor working conditions, inadequate resources for work, lack of motivation, and bad behavior of boss.

Pull factors: High salary, career advancement/promotion, organization is located in a good region/city, more financial benefits, better resources for work, good organizational support, less workload, and higher education opportunities.

Operational Definition and Measurement

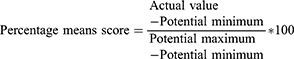

Turnover intention: The employee’s intent or predisposition to leave the work which one is presently employed in, and look forward to finding other work soon. It was measured by a five-point Likert scale of strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, and strongly agree and assessed using four items; “I plan to leave this Work as soon as possible, Under no circumstances would I voluntarily leave this Work, I would be reluctant to stay in this Work and I plan to stay in this Work as long as possible”.The scale was reliable with Cronbach’s alpha 0.936. Respondents were considered to have turnover intention for the job when the total score (agree/strongly agree) was greater than the percent mean for the subscale.

Data Collection Procedure and Tool

The quantitative data were collected by self-administered structured questionnaire which was adapted from another study on factors affecting turnover intention: a case of university teachers in Pakistan.16 The questionnaire consists of socio-demographic, personal factors, pull factors, push factors, and turnover intention questions. Each item except for in the socio-demographic section have a five-point Likert-type scale (ranging from 1= strongly disagree, 2=disagree, 3=Not sure, 4=agree, 5=strongly agree). Dimensions of factors affecting turnover intention included personal factors (eight items), pull factors (eight items), and push factors (seven items). Four questions were prepared to measure turnover intention. The interview guide was used for qualitative data collection through probing of health extension workers and cadres following the information they had provided. The qualitative data were collected at a favorable time and place for the interviewee.

Data Quality Control Measures

Quantitative Part

Orientation was given for one day including a pre-test for facilitators on the objective of the study and technique of data collection by the principal investigator. The pre-test was conducted on 5% of the study participants, that was not included in the study (in Haluu districts), and based on the results necessary modification was followed. The questionnaire was modified based on pre-test and expert opinions to improve the readability, and thus it has face validity. Completeness and consistency of data were ensured every day during data collection.

Qualitative Part

To become acquainted with the situation, to test for misinformation, and to build trust, long-lasting engagement with IDI participants took place, and adequate time was invested. Participants who were prepared to offer data freely and genuinely willing to take part were involved in the study. Transferability was assured by describing the behavior and experiences of the participants with their context so that the behavior and experiences become meaningful to an outsider. Dependability and conformability were assured through transparently describing the research steps taken from the start of a research proposal to the development and reporting of the findings. The interviews took place in an isolated room where participants could talk while free from any person who can directly or indirectly influence their career. The records of the research path were kept throughout the study.

Data Analysis

Quantitative Part

To ensure data quality, the data were entered using Epi-data 3.1 and exported to SPSS version 22 for analysis. The frequency distributions were re-checked for more errors and summarized and organized using appropriate descriptive measures and tables. For analysis, dummy variables were created for independent variables, and summation of dependent variable subscales taken as a continuous variable. Those independent variables with P-value less than 0.25 during bivariate linear regression analysis were entered into multiple linear regression analysis. To identify determinants of health extension workers’ turnover intention for the job, multiple linear regression analysis was done. A significance level of 0.05 was used in all cases. The assumptions in multiple linear regressions (linearity, normality, and multicollinearity) were checked. Prevalence of turnover intention was calculated by percent mean using the following formula:

Qualitative Part

The qualitative tape-recorded data were transcribed into Afan Oromo then translated to English. Accordingly, each text was read again and again carefully and then codes were generated. Data relevant to each code were collected together. Then codes were grouped through constant comparison of concepts, like with like, into three major themes. It was checked whether the themes worked with the coded extracts.

Ethical Approval and Consent to Participate

Ethical clearance and approval to conduct the research were obtained from Jimma University Institute of health, Ethical Review Board. The official letter was written to the Illubabora Zonal health office by Jimma University and consequently, the Illubabora Zone health office wrote to each selected district health office. Before the interview, each respondent was told about the aim of the study, and the possible benefit from the study. Participant informed consent included publication of anonymized responses, and this study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Respondents were assured that they have a full right to refuse to participate whether at the beginning or the middle of the interview without any negative connotation on their future service. Confidentiality was secured by informing them that they are not asked to mention their name on the questionnaire and also they are told that their responses will not in any way be linked to them.

Results

The Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

Out of the planned 245 health extension workers, all of them took part in the study, making the response rate 100%. The mean age of the respondents (+ SD) was 30.58 + 5.26 years. 175 (71.4%) of the respondents were level IV, while 70 (28.6%) were level III. Among respondents, 160 (65.3%) were married and 43 (17.4%) were divorced. Among the respondents, 84 (34.3%) had work experience of more than 10 years and 71 (29%) respondents had 6–10 years of experience (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Socio-Demographic Characteristics Among Health Extension Workers in Health Posts of Illubabora Zone, Southwest Ethiopia, April 2020 |

Magnitude of Turnover Intention

Fifty-two percent of Health Extension Workers had turnover intention. The turnover intention was highest among HEW with service length greater than 10 years (34.4%) followed by those who had served 6–10 years (30.5%). According to the educational status category, 91 (30.5%) and 31 (69.5%) of level IV and III participants had turnover intentions, respectively. Turnover intention linked with marital status was 14.8% for single, 61.7% for married, 21.1% for divorced, and 2.3% for widowed. From the overall turnover intention, highest prevalence of turnover intention was in the age category 26–30 years (40.6%) followed by 31–35 years (25%), 20–25 years (17.2%), 36–40 years (14.1%), and above 41 years (3.1%).

Sociodemographic Predictors of Health Extension Workers’ Turnover Intention

Among the four variables, age was a candidate for multivariate analysis. Health extension workers with age 36–40 years had a 0.656 average decrease in turnover intention when compared with age category 25–29, and those with age above 40 years had a 0.656 average decrease in turnover intention when compared with age category 25–29 years (Table 2).

|

Table 2 Association of Socio-Demographic Characteristics and Turnover Intention Among Health Extension Workers’ in Illubabora Zone, Oromia Regional State, Southwest Ethiopia, April 2020 |

Personal Factors

The significant variables at bivariate analysis, among push factors, were health problems, children’s education, health extension being a difficult job and expectations not fulfilled. Health extension workers who strongly disagreed in health problem as their reason for turnover intention had an average of 3.352 decrease in turnover intention score compared with those who agreed. But concerning health extension workers, those who strongly agreed on the absence of good educational opportunities for their children as their reason for turnover intention had an average 1.919 increase in turnover intention score compared with those who disagree, and likewise, those who were strongly agreed on health extension being a difficult job had an average 2.079 increase in turnover intention score when compared with those who agreed. Health extension workers who strongly disagreed in their expectation not fulfilled had a 3.424 unit reduction in turnover intention score compared with those who strongly agreed (Table 3).

|

Table 3 Personal Factors Associated with Intent to Leave Among Health Extension Workers in Health Posts of Illubabora Zone, South West Ethiopia, April 2020 |

Pull Factors

Three pull factors were significantly associated with bivariate linear regression. These are high salaries, career advancement, and higher educational opportunities. Among health extension workers who agreed that they were attracted to high salary had an average 3.391 increase in turnover intention score when compared with those who disagreed, and those who strongly agreed that they were attracted to high salary had an average 2.900 increase in turnover intention score when compared with those who disagreed. Health extension workers who strongly agreed to being attracted to career advancement had a 2.706 increase in turnover intention score compared with those who agreed. On contrary, the health extension workers who strongly disagreed to being attracted to higher educational opportunities had a 6.609 unit decrease in turnover intention compared with those who strongly agree (Table 4).

|

Table 4 Pull Factors Associated with Intent to Leave Among Health Extension Workers in Health Posts of Illubabora Zone, South West Ethiopia, April 2020 |

Push Factors

Five push factors were significantly associated with bivariate linear regression. These are poor incentives, inadequate resources, and high workload, a lack of motivation, and a lack of career opportunities. Health extension workers who were neutral in poor incentive had a −2.251 average decrease in turnover intention when compared with those who strongly agreed. And those who were agreed in poor incentive hada −3.014 average decrease in turnover intention when compared with those who strongly agreed. Health extension workers who disagreed in inadequate resource had a −2.201 average decrease turnover intention when compared with those who agreed. Those who were neutral for inadequate resources had a −2.223 average decrease in turnover intention when compared with those who agreed. Health extension workers who strongly disagreed in high workload had a −3.221 average decrease in turnover intention when compared with those who strongly agreed; and also those who disagreed with the high workload had a −2.243 average decrease in turnover intention when compared with those who strongly agreed. Health extension workers who strongly disagreed in lack of motivation had a −3.482 average decrease in turnover intention when compared with those who strongly agreed. Health extension workers who disagreed in lack of motivation had a −3.283 average decrease in turnover intention when compared with those who strongly agreed. Health extension workers who disagreed in limited career opportunity had a −3.155 average decrease in turnover intention when compared with those who strongly agreed. Those who were neutral in lack of career opportunity had a −3.499 average decrease in turnover intention when compared with those who strongly agreed (Table 5).

|

Table 5 Push Factors Associated with Intent to Leave Among Health Extension Workers in Health Posts of Illubabora Zone, South West Ethiopia, April 2020 |

Multivariate Analysis

The final model was constructed using backward linear regression. Multivariate analysis was undertaken and those with a P-value less than 0.05 were taken as predictors as shown below. Among those predictors, lack of motivation, high workload, and lack of career opportunity was statistically significant associations under multivariate analysis (Table 6).

|

Table 6 Final Predictors of Turnover Intention Among Health Extension Workers in Illubabora Zone, Oromia Regional State, Southwest Ethiopia, April 2020 |

Health extension workers who were neutral in lack of motivation had an average 2.801 decrease in turnover intention score when compared with those who strongly agreed; and those who were agreed in lack of motivation had an average 2.359 decrease in turnover intentions when compared with those who strongly agreed. In in-depth interviews, most of the health extension cadres stated that lack of overtime payment, weak rewarding system, having to travel a long way on foot to reach the community on an uncomfortable road, degraded health post infrastructure and inaccessibility of utilities such as water and electricity are among reasons that demotivate health extension workers. One health extension cadre with the age of 40 said that

We did our work day and night but nothing is being paid for what we did during the night/over time which is paid for other health professionals, and also currently the rewards system which had been given for those who did outstanding performance is paralyzed. (Participant 3)

Another interviewed health extension cadre of 36 years old said that “Working in rural health post is boring because we walk a long way on foot to reach the community in the difficult road” (participant 2). Besides, “ currently health posts are degrading, accessibility of water and electricity is null. Generally I can say we are demoralized” (participant 5).

Health extension workers who strongly disagreed with high workload had an average decrease of 3.350 turnover intention score when compared with those who strongly agreed. In in-depth interviews, all respondents stated that a high work load remarkably increases health extension worker’s turnover intention. The health extension workers were obliged to execute different sectors’ tasks other than those in the health sectors, as a result, there would be an elevated workload on the existing health extension worker. A worker with the age of 38 clarified that

… we did other sector task other than health sector task like, agricultural tasks (distributing fertilizer, digging dam etc.), education sector tasks, political task (collecting members’ premium) which makes us very bored. Even there is a time when we go through the health tasks totally … (Participant 1)

Health extension workers who were neutral in lack of career opportunity had a 3.452 units decrease in turnover intention score when compared with those who strongly agreed. Most of the health extension cadres also complained about career structure. They replied that there was no career advancement for health extension workers which left their growth unchanged. Due to this fact, they intended to leave this job. One health extension cadre of 40 years old stated that: “We have limited steps to grow into like teachers of similar service years’. They grow every two years but we … ” (Participant 6)

Discussion

The study assesses turnover intention and factors affecting rural Health Extension Workers of Illubabora Zone. According to this study the overall magnitude of turnover intention among HEWs was 52%, suggesting that more than half of Health Extension Workers intended to leave their current job. This finding was higher than a study conducted in China which shows 29.1% of rural HEWs intended to leave.27 The possible explanation might be the difference in the study area. This study area might have poor access of electric utility, roads and safe water which forces them to leave their job. In contrary, this finding is lower than a study conducted on Chinese village doctors which indicates 63.2%of them intended to leave.28 This variation might be due to differences in the educational qualification. In the previous study, educational qualification included masters and above whereas in this study the maximum educational status was level IV (diploma). For this reason, they might have a high job opportunity and this encourages their intention to leave their job as compared with HEWs.

In this study lack of motivation was associated with the turnover intention of the current job. Health extension workers who were neutral (not sure) about their lack of motivation had an average 2.801 decrease in turnover intention score when compared with those who strongly agreed to lack of motivation. Those who agreed in lack of motivation had an average 2.359 decrease in turnover intention score when compared with those who strongly agreed. This finding is consistent with a study conducted in Jimma Zone.29 This might be due to employees who are motivated being committed and linked passionately to the organization’s goals and strategies which might result in intention to stay in their current work. This finding will help different levels of government structure to develop a plan about motivation to enhance retention of HEWs. Furthermore, the study stretches guidelines to HR practitioners to give prime attention to motivation as they assist in retaining the talent. Like any other health professionals, to enhance their motivation, HEWs should earn overtime payment to motivate them. The proclamation of Ethiopia labor force grants overtime payment for those doing over eight hours per day.30 Vehicles should be provided by a responsible government body to solve the long-distance challenge of health posts’ catchment areas. Moreover, renovation of degraded health posts along with installing water and electricity accessibility is necessary together with motivating through a practical reward mechanism those who do outstanding work.

Health extension workers who strongly disagreed that they had high workload had an average 3.350 decrease in turnover intention score as related to those who strongly agreed that they had a high work load. Health extension workers often needed to work too much compared with other professionals. As mentioned by qualitative finding the reason might be HEWs were obliged to execute different sector’s tasks other than those of the health sector. A high workload might reduce job performance and adversely influence workers’ health. A crisis in providing highquality, safe health care and in excessive turnover might be the consequence of a high workload.31 If some HEWs quit the job due to work overload, then those who stay in position will encounter even more work, and thus lead to the stronger intention of leaving their job. So decreasing the workload is the proposed solution. Then in our case avoiding workload from other sectors needs to be considered. To avoid workload from other sectors the government should attempt to encourage them to only work on the Health Extension Program and to address another sector’s tasks via the respective government structure.

Lastly, health extension workers who were neutral (not sure) in the limitedness of their career opportunities had an average 3.452 decrease in turnover intention score when compared with those who strongly agreed to their limitedof career opportunities. This might be due to employees who are pessimistic about the career growth opportunities offered are motivated, which in turn leads to higher commitment and lower turnover intention. As a result evidence of the study suggests amendment of career structures would have a critical role in reducing turnover intention of health extension workers.

Limitation of Study

The self- administered questionnaire employed for data collection might result in potential missed values. But, to overcome this drawback, the respondents were explained the purpose and relevance of their response appropriately by which the investigators had reduced almost all the potential limitation.

Generalizability

The potential generalizability of the evidence generated by this study to other settings should be considered because of the study setting, context, methods, and limitations described in this study.

Conclusion

Overall, the health extension workers’ turnover intention working in Illubabora Zone was high, which can greatly affect primary health care. The significant variables of turnover intention were lack of motivation, high workload, and limited career structure. Our results could serve as a reference for institutional and policy measures aimed at preventing or controlling health extension workers’ turnover intentions. Strategic responses are needed to control turnover at health posts and guide human resource management. Amendment of career structure and overtime payment should be made to retain HEWs. In addition to encouraging HEWs to working only on health sector tasks, providing transportis a good way to reduce the workload. Renovating health posts, building the necessary infrastructure and a practical reward mechanism should be implemented to increase motivation and lower turnover intention among health extension workers.

Acknowledgment

Our sincere gratitude goes to the Institute of Health, Jimma University, and Illubabora Zone health department for facilitating this study. Finally, our special respect goes to all respondents and data collectors in this study.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Wang H, Tesfaye R, NV Ramana G, Chekagn CT. Ethiopia Health Extension Program: An Institutionalized Community Approach for Universal Health Coverage. The World Bank; 2016.

2. (ET), F. M. o. H. Health extension program in Ethiopia: profile [Internet]. Addis Ababa: Health extension and Education Center; 2007 [cited May 24, 2011]:27. Available from: http://www.ethiopia.gov.et/English/MOH/Resources/Documents/HEW%20profile%20Final%2008%2007.pdf..

3. Center for National Health Development in Ethiopia, C. U. Ethiopia Health Extension Program Evaluation Study, 2005–2010, Volume‐IV. Support and Management of HEP; 2011.

4. Abera F Assessment of the magnitude of attrition and exploring factors related to it among Health Extension Workers deployed in Oromia Region. Addis Abeba University Repository; 2011. Available from: www.aau.edu.et.

5. FMoH. Health sector transformation plan Addis Abeba, Ethiopia; 2015.

6. Birhanu Darega ND. Challenges of maternal health services utilization and provision from Health Posts in Bale Zone, Oromiya Regional State, Southeast Ethiopia: qualitative Study. Prim Health Care. 2015;5. doi:10.4172/2167-1079.1000189.

7. Nanncarrow S, Bradbury J, Pit SW, Ariss S. Intention to stay and intention to leave: are they two sides of the same coin? A cross-sectional structural equation modelling study among health and social care workers. J Occup Health. 2014:

8. Bartanen B, Grissom JA, Rogers LK. The impacts of principal turnover. Educ Eval Policy Anal. 2019;41:350–374. doi:10.3102/0162373719855044

9. Pandita D, Ray S. Talent management and employee engagement–a meta-analysis of their impact on talent retention. Ind Commerc Train. 2018;50(4):185–199. doi:10.1108/ICT-09-2017-0073

10. Li Y, Sawhney R, Tortorella GL. Empirical analysis of factors impacting turnover intention among manufacturing workers. Int J Bus Manag. 2019;14:1–18. doi:10.5539/ijbm.v14n4p1

11. Griffeth RW, Hom PW, Gaertner S. A meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: update, moderator tests, and research implications for the next millennium. J Manage. 2000;26:463–488. doi:10.1177/014920630002600305

12. Mansour S, Tremblay DG. Work–family conflict/family–work conflict, job stress, burnout and intention to leave in the hotel industry in Quebec (Canada): moderating role of need for family friendly practices as “resource passageways”. Int J Hum Resour Manag. 2018;29:2399–2430. doi:10.1080/09585192.2016.1239216

13. Hann M, Reeves D, Sibbald B. Relationships between job satisfaction, intentions to leave family practice and actually leaving among family physicians in England. Eur J Public Health. 2011;21:499–503. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckq005

14. Zhang Y, Feng X. The relationship between job satisfaction, burnout, and turnover intention among physicians from urban state-owned medical institutions in Hubei, China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:235. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-11-235

15. Otieno OC, Liyala S, Odongo BC, Abeka SO. Theory of reasoned action as an underpinning to technological innovation adoption studies; 2016.

16. Shah IA, Fakhr Z, Ahmad MS, Zaman K. Measuring push, pull and personal factors affecting turnover intention: a case of university teachers in Pakistan. Rev Econ Bus Stud. 2010;3:167–192.

17. Ferede A, Kibret GD, Million Y, Simeneh MM, Belay YA, Hailemariam D. Magnitude of turnover intention and associated factors among health professionals working in public health institutions of north shoa zone, amhara region, Ethiopia. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:1–9. doi:10.1155/2018/3165379

18. Kalifa T, Ololo S, Tafese F. Intention to leave and associated factors among health professionals in jimma zone public health centers, Southwest Ethiopia. Open J Prev Med. 2016;6:31–41. doi:10.4236/ojpm.2016.61003

19. Worku N, Feleke A, Debie A, Nigusie A. Magnitude of Intention to Leave and Associated Factors among Health Workers Working at Primary Hospitals of North Gondar Zone, Northwest Ethiopia: mixed Methods. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:1–9. doi:10.1155/2019/7092964

20. Debela TF, Salgedo WB, Tsehay YE. Predictors of intention-to-leave the current job and staff turnover among selected health professionals in Ethiopia. Glob J Manag Bus Res. 2017.

21. Dellie E, Biks GA, Asrade G, Gebremedhin T. Intentions to leave and associated factors among laboratory professionals working at Amhara National Regional State public hospitals, Ethiopia: an institution-based cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12:1–7. doi:10.1186/s13104-019-4688-z

22. Udessa H, Beyene W, Yitbarek K Health professionals’ intention to leave and associated factors in public health centers of guji zone, south est Ethiopia; 2018.

23. Asegid A, Belachew T, Yimam E. Factors influencing job satisfaction and anticipated turnover among nurses in Sidama zone public health facilities, South Ethiopia. Nurs Res Pract. 2014;2014:1–26. doi:10.1155/2014/909768

24. Gizaw A, Lema T, Debancho W, Germossa G. Intention to stay in nursing profession and its predictors among nurses working in Jimma Zone Public Hospitals, South West Ethiopia. J Nurs Care. 2017;7:1–8. doi:10.4172/2167-1168.1000440

25. Chegini Z, Asghari Jafarabadi M, Kakemam E. Occupational stress, quality of working life and turnover intention amongst nurses. Nurs Crit Care. 2019;24:283–289. doi:10.1111/nicc.12419

26. Kols A, Kibwana S, Molla Y, et al. Factors predicting Ethiopian anesthetists’ intention to leave their job. World J Surg. 2018;42:1262–1269. doi:10.1007/s00268-017-4318-7

27. Liu J, Zhu B, Wu J, Mao Y. Job satisfaction, work stress, and turnover intentions among rural health workers: a cross-sectional study in 11 Western provinces of China. BMC Fam Pract. 2019;2:1–11.

28. Fang P, Liu X, Huang L, Zhang X, Fang Z. Factors that influence the turnover intention of Chinese village doctors based on the investigation results of Xiangyang City in Hubei Province. Int J Equity Health. 2014;13:1–9. doi:10.1186/s12939-014-0084-4

29. Yasin M Assessment of level motivation and associated factors among health extension workers in jimma zone, southwest ethiopia. Jimma University repository; 2011. Available from: https://www.ju.edu.et.

30. Sommer M National labour law profile: federal democratic republic of Ethiopia. Geneva: ILO; 2003.

31. Kim SK. Safety and health effects and countermeasures of long-term labor by service physicians. Med Policy Forum. 2016;14:53–63.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.