Back to Journals » International Journal of General Medicine » Volume 16

Transient Anosmia and Dysgeusia in COVID-19 Disease: A Cross Sectional Study

Authors Ali FA, Jassim G , Khalaf Z, Yusuf M, Ali S, Husain N, Ebrahim F

Received 15 February 2023

Accepted for publication 17 May 2023

Published 12 June 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 2393—2403

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S408706

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Prof. Dr. Héctor Mora-Montes

Fatema Ahmed Ali,1 Ghufran Jassim,2 Zahra Khalaf,3 Manaf Yusuf,4 Sara Ali,5 Nada Husain,6 Fatema Ebrahim6

1Department of Internal Medicine, South West Acute Hospital, Western Health and Social Care Trust, Enniskillen, Northern Ireland, UK; 2Family Medicine Department, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland — Medical University of Bahrain (RCSI Bahrain), Busaiteen, Kingdom of Bahrain; 3Department of Postgraduate Studies, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Dublin, Ireland; 4Children’s & Adolescent Services, Leeds General Infirmary, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Leeds, UK; 5Ministry of Health Bahrain, COVID-19 National Team, Sanabis, Kingdom of Bahrain; 6Department of Internal Medicine, Private Health Sector, Manama, Kingdom of Bahrain

Correspondence: Ghufran Jassim, Family Medicine Department, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland — Medical University of Bahrain (RCSI Bahrain), Busaiteen, Kingdom of Bahrain, Email [email protected]

Objective: This study aims to explore the prevalence of anosmia and dysgeusia and their impact on COVID-19 patients.

Methods: This is a cross-sectional study. Patients diagnosed with COVID-19 between 1st October 2020 and 30th June 2021 were randomly selected from a national COVID-19 registry. COVID-19 cases were diagnosed using molecular testing method which measured the viral E gene. The Anosmia Reporting Tool, and a brief version of the questionnaire on olfactory disorders were used to measure the outcomes via telephone interviews. Data were analysed using SPSS 27 statistics software.

Results: A total of 405 COVID-19 adults were included in this study, 220 (54.3%) were males and 185 (45.8%) were females. The mean±SD age of participants was 38.2 ± 11.3 years. Alterations in the sense of smell and taste were reported by 206 (50.9%), and 195 (48.1%) of the patients, respectively. Sex and nationality of participants were significantly associated with anosmia and dysgeusia (p < 0.001) and (p-value=0.001) respectively. Among patients who experienced anosmia and dysgeusia, alterations in eating habits (64.2%), impact on mental wellbeing (38.9%), concerns that the alterations were permanent (35.4%), and physical implications and difficulty performing activities of daily living (34%) were reported.

Conclusion: Anosmia and dysgeusia are prevalent symptoms of COVID-19 disease, especially among females. Although transient, anosmia and dysgeusia had considerable impact on patient’s life. Neuropsychological implications of COVID-19 in acute infection phase and prognosis of anosmia and dysgeusia in COVID-19 are areas for further exploration.

Keywords: anosmia, taste, smell, COVID-19, dysgeusia, quality of life

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2).1 The common symptoms of COVID‐19 include dry cough, fever, dyspnea, fatigue, anorexia, diarrhea, chest pain, headache, nausea, vomiting, dysnea and muscle ache while other patients remain asymptomatic.2 The diagnosis of COVID-19 is based on the clinical suspicion, computerised tomography (CT) findings, and a reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction molecular test (RT-PCR)3 loss of smell (anosmia) and taste (dysgeusia) sensations are common neurological findings of the disease.4,5

Anosmia is part of olfactory dysfunction where the person is unable to sense smell or detect odour.6 Dysgeusia is a sensory dysfunction where the individual loses the perception of taste.7 The global prevalence of these symptoms in patients with COVID-19 is 40–50% on average4 and up to 98% showing olfactory dysfunction when tested objectively.8

Although, most patients gradually regain their sense of smell and taste, the mechanism of these dysfunction is not fully understood.9 Post-infectious olfactory dysfunction is thought to be the result of involvement of the olfactory bulb and damage to the olfactory receptor cells due to the neurotrophic features associated with SARS-CoV-2.10 Minimal data are available for the mechanism of taste disorders among patients with COVID 19, Single cell RNA-sequencing studies showed that epithelial cells of the tongue express ACE-2 receptors where buccal mucosa may play a role in entry of SARS-COV2. Additionally, indirect damage of the taste receptors through infection and inflammation of the epithelial cells are hypothesised to play a role in the pathogenesis.11

A review of the literature showed that the prevalence of anosmia ranged between 22% and 68%.12 Regionally, a study conducted in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia reported that the prevalence of olfactory dysfunction, anosmia and hyposmia was 53%, 32.7% and 20.3%, respectively. Patients aged 15–39-year-old were mostly affected, and the prevalence of olfactory dysfunction was higher among females (60.3%) compared to males (56.5%).13 In the same study, the prevalence of ageusia was determined at 51.4%.9 The loss of taste and smell senses is mostly transient lasting between one and two weeks. However, few chronic cases lasting more than one year after diagnosis have been reported.

Few studies explored the impact of anosmia and dysgeusia on patients with COVID-19 and reported negative impact of these symptoms, interference with daily activities and deterioration in well-being.9,14,15 A study conducted in the eastern region of Saudi Arabia reported that 23% of participants felt isolated, 12.6% reported having problems with taking part in daily activities, anger in 28.2%, difficulty in relaxing in 21% of participants, and worrying about their ability to cope with their changes in sense of smell in 22%.9

In view of their predominance as signs and symptoms of the disease and in light of their substantial impact on quality of life, there is a need to study the frequency of these two symptoms, establish their association with COVID-19 diagnosis, and whether they are prognostic factors for COVID-19 outcomes. Anosmia and dysgeusia are among the earliest symptoms observed in COVID-19 patients and the manifestation of anosmia and dysgeusia could be used as an early warning for SARS-CoV-2 infection.10 Consequently, in-depth analysis of this dysfunction and its relation to the pathogenesis and severity of the disease will inform the decision-making process and communication between the health-care provider and patients encountering these symptoms. Further, there are wide variations in the reported prevalence of anosmia/hyposmia and ageusia/dysgeusia across different regions, potentially suggesting variable geographical presentation.12 Therefore, it is imperative that we further examine these symptoms in the Bahraini context.

This study aims to estimate the prevalence and risk factors of olfactory and gustatory dysfunction in patients infected with Covid-19 and to investigate their impact on patient’s life.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Setting

This is a cross-sectional study that explores olfactory and gustatory dysfunction of COVID-19 infection in adult patients who were previously infected with coronavirus in Bahrain. The inclusion criteria were people aged 18 years and more who contracted COVID-19 between October 2020 and June 2021. We excluded patients who had pre-existing histories of olfactory or taste dysfunction.

Participants and Procedure

We estimated that 385 participants are needed to measure the prevalence of smell and taste dysfunction using this formula:

Where n = sample size, Z = Z statistic for a level of confidence, P = expected prevalence or proportion, d=Precision.

Patients who contracted COVID-19 between October 2020 and June 2021 were randomly selected using a computer-generated randomization system from the national database of COVID-19. A total of 578 COVID-19 patients were contacted, to account for non-response rate of 30%. Data collection was conducted between June 2021 and August 2021 using telephone-based questionnaires.

Ethics Consideration

Prior to data collection, patients were informed about the purpose of the research and consent was obtained. Ethics approval was obtained from RCSI Bahrain and the National COVID-19 Ethics Committee.

Study Instrument

The questionnaire’s questions were adopted from two validated tools. The first tool is the “Anosmia Reporting Tool”, which was developed by the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS),16 is used to study the prevalence and pattern of anosmia and dysgeusia in COVID patients as well as the associated risk factors. The questionnaire included 17 questions, with 1 question asking about both anosmia and dysgeusia. To obtain more detailed data, we expanded this question and separated anosmia and dysgeusia questions from each other. The questions are evolving around definition of anosmia and dysgeusia, their onset, timing, duration, associated symptoms, and resolution of symptoms. The tool was developed in March 2020 by the AAO-HNS and can be found at: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0194599820922992#supplementary-materials.

The second is the “brief version of the questionnaire of olfactory disorders”,17 which is used to study the impact of anosmia and dysgeusia during COVID infections on patient’s life. The tool can be accessed at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6773507/#:~:text=The%20Questionnaire%20of%20Olfactory%20Disorders%20%2D%20Negative%20Statements%20(QOD%2DNS,time%20required%20to%20complete%20questionnaires. The tool consists of 7 questions and is composed of four domains: social, anxiety, eating and annoyance.

The final questionnaire included four sections: patients’ socio-demographics and clinical characteristics, an assessment of the sense of smell, assessment of the sense of taste, and the impact of anosmia and ageusia on patients’ life.

Statistical Analysis

The data was entered into the SPSS 27 statistics software (IBM Corp., Chicago, IL, USA) for statistical analysis. Descriptive analysis was performed to present categorical variables as frequencies and percentages, whereas continuous variables were presented as means (SD), median and range. Inferential analysis was performed to test the associations between patients’ socio-demographics, risk factors (including smoking status, vaccination status, and comorbidities) and the status of their senses of smell and taste using ANOVA, t-test or Chi square as appropriate. Statistical significance was deduced if p-values were 0.05 or less. Binomial regression analysis was utilized to determine significant predictors of alterations in taste and smell.

Results

Characteristics of Participants

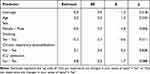

A total of 578 COVID-19 patients were contacted; of these, 405 adult patients consented to participation and 173 patients were excluded. Reasons for exclusion were: 54 had missing contact details, 45 had invalid contact numbers, 27 did not respond to phone calls, 20 refused to participate, 26 due to language barriers, and 1 person passed away. No participants were excluded due to history of smell/taste disorders (Figure 1). Out of 405 participants, 220 were males (54.3%) and 185 were females (45.8%). The mean age of participants was 38.2 years ± 11.3 years (median age: 36 years). Most patients were Bahrainis (n = 270, 66.7%). The non-Bahrainis were from South Asia (n = 104, 25.7%), East Asia (n = 13, 3.2%), Arabic countries outside the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) (n = 11, 2.7%), the GCC (n = 5, 1.2%), and from other nationalities (n = 2, 0.5%). Seventy-eight percent of the participants were married (n = 309), 19.4% were single (n = 77), 2% were divorced (n = 8), and 0.5% were widowed (n = 2). Further, 56.2% of participants had received COVID vaccines (n = 223), while 43.8% were not vaccinated (n = 174) [Table 1].

|

Table 1 The Sociodemographic and Clinical Data of Participants |

|

Figure 1 Flow chart of patient recruitment. |

Close contact with COVID positive individuals was reported by 67.4% of the participants (n = 273). Twenty percent of participants were smokers (n = 81). Other comorbidities were sinusitis or allergies (15.3%), diabetes mellitus (13.1%), hypertension (12.8%), and chronic respiratory conditions (3.5%) [Table 1].

Clinical Presentation of COVID-19 and the Treatment Course

Regarding the clinical presentation of COVID-19, the most prevalent symptoms were malaise (73.8%), fever (64%), cough (54.3%), headache (51.6%), anosmia (50.9%), and dysgeusia (48.1%). On the other hand, 22.4% of COVID patients were asymptomatic. [The frequencies and percentages of other symptoms are outlined in Table 1]. The treatment requirements were: symptomatic treatment (61.5%), no treatment (25.9%), and more invasive forms of treatment (12.6%). Hospitalization was required in 21.7% of patients (n = 88) and 5.5% of participants were admitted to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) (n = 22) [Table 2].

|

Table 2 The Clinical Presentation of COVID Within the Studied Cohort |

Prevalence of Anosmia and Dysgeusia

Out of 405 participants, changes in the sense of smell were experienced by 206 (50.9%), and changes in sense of taste were experienced by 195 (48.1%) of the patients, respectively.

Associations Between Anosmia, Dysgeusia and Demographics of Participants

Sex of participants and nationality were significantly associated with anosmia and dysgeusia, with higher prevalence among females (60.5%) compared to males (42.4%) (p < 0.001) as well as among Bahrainis (p-value=0.001) compared to non-Bahrainis [Table 3].

|

Table 3 Associations Between Anosmia/Dysgeusia and Patient Characteristics |

Age was not associated with either anosmia and dysgeusia (P = 0.133 and P = 0.172 respectively).

Impact of Anosmia and/or Ageusia on Patients’ Life

Out of those who reported anosmia and/or dysgeusia, 64.2% reported alterations in eating habits, 38.9% impact on mental wellbeing, 35.4% concerns that the senses of taste and smell would not return, and about 34% had physical implications and difficulty performing activities of daily living [Table 4]. About one-third found it hard to relax and 20% either felt angry or isolated.

|

Table 4 Impact of Anosmia and/or Ageusia on Patients’ Life |

Binomial Regression Model for Anosmia

Table 5 shows the results of binomial regression model for loss of smell as the dependent variable and including the predictors: age, sex, smoking status, chronic respiratory disease, and ICU admission as the independent variables. The predictors explained 2.6% of the variation in loss of smell (R2 = 0.026). The only significant predictor that influenced loss of smell is sex of participants (P = 0.001).

|

Table 5 Binomial Regression Model Coefficients – Did You Experience Any Changes in Your Sense of Smell? |

Binomial Regression Model for Dysgeusia

Table 6 shows the results of binomial regression model for dysgeusia as the dependent variable and including the predictors: age, sex, smoking status, chronic respiratory disease, and ICU admission as the independent variables. The predictors explained 2.4% of the variation in dysgeusia (R2 = 0.024). The only significant predictor that influenced dysgeusia is sex of participants (P = 0.001) (Table 6).

|

Table 6 Binomial Regression Model Coefficients – Did You Experience Any Changes in Your Sense of Taste? |

Discussion

This is a cross-sectional study that highlights the prevalence and risk factors for anosmia and ageusia in patients diagnosed with COVID-19 and their impact on patients’ life. It involves 405 patients diagnosed between October 2020 and June 2021 in the Kingdom of Bahrain.

The study reported that almost half of the studied patients experienced either or both symptoms (anosmia and/or dysgeusia). The co-presentation of anosmia and dysgeusia was more prevalent than either of the symptoms alone. This is in comparison to a worldwide pooled prevalence of 38.2% for anosmia and 36.6% for dysgeusia.18 The wide variation in the reported prevalence is mainly attributed to the measurement bias whereby various tools with wide range of sensitivity were used in several studies.19 Further, the prevalence of olfactory and taste dysfunction following Covid-19 is possibly underestimated and is attributed to the subjective assessment of these symptoms.18,19

Our study reported a significantly higher prevalence of anosmia/dysgeusia amongst female compared to male participants. Similar findings were observed in studies conducted in Saudi, Italy, and Switzerland.20,21 However, this variation between sexes was not significant in other studies.22–25 Possible reasons for this discrepancy in results across studies are the differences in methodology, symptom definition, population studied, measurement tool and recall bias as data was mainly dependent on self-reporting of symptoms. The literature discusses potential biological differences between genders in ACE receptor expression and its location on the X-chromosome, and differences in baseline olfaction as possible explanations to the increased prevalence of these symptoms amongst females.26,27 Both human cell receptors ACE2 and TMPRSS2 are essential for the SARS-CoV-2 entrance. These receptors are mostly present in the olfactory epithelium cells. Therefore, the main hypothesis is that anosmia is caused due to damage to non-neuronal cells which, thereafter, affects the normal olfactory metabolism. A possible explanation for the higher prevalence among females would be that incomplete X chromosome inactivation would contribute to increased expression of ACE2.28

Symptoms related to smell and taste were generally associated with milder forms of the disease studied in the acute or initial phase.29 It is not yet clear if these symptoms have a higher impact on morbidity and mortality in the long term, especially with the possibility of neurological pathophysiology. Studies have reported significant associations of neurological burden and infection with SARS-CoV2, explaining the potential connection with entry through the olfactory bulb.30,31 In addition, recent studies demonstrated the association of microinvasive SARS-CoV2 and respiratory failure, emphasizing the importance of future research on neurological impacts of COVID-19.32

Smoking has been a debatable risk factor for anosmia/dysguesis or its recovery in the literature. While some studies reported that smoking is more prevalent among smokers and is adversely related to anosmia recovery,22,33,34 others found no significant difference compared with non-smokers or reported a favourable/protective effect for smoking on the recovery time.19,35–38 In our study, smokers were more likely to experience loss of smell and taste compared to non-smokers; however, this difference did not reach statistical significance.

Comparable rates of impact of anosmia and dysgeusia were reported by other studies.9,15,39,40 The main concerns were that the senses of taste and smell would not return, alteration of eating habits, feeling angry and difficulty performing daily activities. While greater attention is being paid to curbing other COVID-19 related symptoms as well as rolling out the vaccines, the prognosis of Covid-19 survivors with olfactory and taste dysfunction remains an enigma which will ultimately have a huge impact on patient’s quality of life, especially if the loss or dysfunction is permanent.

Limitations of our study included a small sample size, retrospective design, and reliance on self-reported olfactory or gustatory outcomes by the patients, incomplete medical records, and missing information. Further, this study did not compare the impact of permanent vs transient loss/dysfunction of olfactory and taste. Strengths include random selection of an early cohort of COVID-19 patients from a national registry and using validated tool for outcome measurement.

Conclusion

Anosmia and dysgeusia are prevalent symptoms of COVID19 disease, especially amongst females. Although transient, anosmia and dysgeusia had considerable impact on patient’s life. Sex of participants was the only predictor of these symptoms. Further cohort or case control studies are needed to establish the association and risk factors of anosmia and dysgeusia with the disease ideally involving a control group. Definitive mechanism of action and diagnostic value of anosmia and dysgeusia remain to be verified in future studies. Effective treatment regimen for anosmia and dysgeusia post COVID should be investigated in randomized controlled trials to enhance patient’s quality of life.

Data Sharing Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

Ethics Approval

Ethical approval was obtained from both the Research Ethics committee at Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland – Medical University of Bahrain (RCSI Bahrain) and the National COVID-19 Ethics Committee. The study complies with the declaration of Helsinki.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation; FA and GJ took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; all authors gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interests in this work.

References

1. Wang Y, Wang Y, Chen Y, et al. Unique epidemiological and clinical features of the emerging 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) implicate special control measures. J Med Virol. 2020;92(6):568–576. doi:10.1002/jmv.25748

2. Niazkar HR, Zibaee B, Nasimi A, et al. The neurological manifestations of COVID-19: a review article. Neurol Sci. 2020;41(7):1667–1671. doi:10.1007/s10072-020-04486-3

3. Maia R, Carvalho V, Faria B, et al. Diagnosis methods for COVID-19: a systematic review. Micromachines. 2022;13(8):1349. doi:10.3390/mi13081349

4. Lechien JR, Chiesa-Estomba CM, De Siati DR, et al. Olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions as a clinical presentation of mild-to-moderate forms of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a multicenter European study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;277(8):2251–2261. doi:10.1007/s00405-020-05965-1

5. Nepal G, Rehrig JH, Shrestha GS, et al. Neurological manifestations of COVID-19: a systematic review. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):421. doi:10.1186/s13054-020-03121-z

6. Huynh PP, Ishii LE, Ishii M. What is anosmia? JAMA. 2020;324(2):206. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.10966

7. Samaranayake L, Sadir Fakhruddin K, Panduwawala C. Loss of taste and smell. Br Dent J. 2020;228(11):813. doi:10.1038/s41415-020-1732-2

8. Moein ST, Hashemian SM, Mansourafshar B, et al. Smell dysfunction: a biomarker for COVID-19. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2020;10(8):944–950. doi:10.1002/alr.22587

9. AlShakhs A, Almomen A, AlYaeesh I, et al. The association of smell and taste dysfunction with COVID19, and their functional impacts. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;74(Suppl2):2847–2852. doi:10.1007/s12070-020-02330-w

10. Agyeman AA, Chin KL, Landersdorfer CB, et al. Smell and taste dysfunction in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(8):1621–1631. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.05.030

11. Mastrangelo A, Bonato M, Cinque P. Smell and taste disorders in COVID-19: from pathogenesis to clinical features and outcomes. Neurosci Lett. 2021;748:135694. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2021.135694

12. Carrillo-Larco RM, Altez-Fernandez C. Anosmia and dysgeusia in COVID-19: a systematic review. Wellcome Open Res. 2020;5:94. doi:10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15917.1

13. Mubaraki AA, Alrbaiai GT, Sibyani AK, et al. Prevalence of anosmia among COVID-19 patients in Taif City, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2021;42(1):38–43. doi:10.15537/smj.2021.1.25588

14. Elkholi SMA, Abdelwahab MK, Abdelhafeez M. Impact of the smell loss on the quality of life and adopted coping strategies in COVID-19 patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;278(9):3307–3314. doi:10.1007/s00405-020-06575-7

15. Otte MS, Haehner A, Bork M-L, et al. Impact of COVID-19-mediated olfactory loss on quality of life. ORL. 2023;85(1):1–6. doi:10.1159/000523893

16. Kaye R, Chang CWD, Kazahaya K, et al. COVID-19 anosmia reporting tool: initial findings. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;163(1):132–134. doi:10.1177/0194599820922992

17. Mattos JL, Edwards C, Schlosser RJ, et al. A brief version of the questionnaire of olfactory disorders in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2019;9(10):1144–1150. doi:10.1002/alr.22392

18. Mutiawati E, Fahriani M, Mamada SS, et al. Anosmia and dysgeusia in SARS-CoV-2 infection: incidence and effects on COVID-19 severity and mortality, and the possible pathobiology mechanisms - a systematic review and meta-analysis. F1000Res. 2021;10:40. doi:10.12688/f1000research.28393.1

19. Babaei A, Iravani K, Malekpour B, et al. Factors associated with anosmia recovery rate in COVID-19 patients. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2021;6(6):1248–1255. doi:10.1002/lio2.690

20. Paderno A, Schreiber A, Grammatica A, et al. Smell and taste alterations in COVID-19: a cross-sectional analysis of different cohorts. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2020;10(8):955–962. doi:10.1002/alr.22610

21. Vaira LA, Deiana G, Fois AG, et al. Objective evaluation of anosmia and ageusia in COVID-19 patients: single-center experience on 72 cases. Head Neck. 2020;42(6):1252–1258. doi:10.1002/hed.26204

22. Al-Ani RM, Acharya D. Prevalence of anosmia and ageusia in patients with COVID-19 at a primary health center, Doha, Qatar. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;74(Suppl 2):2703–2709. doi:10.1007/s12070-020-02064-9

23. Al-Rawi NH, Sammouda AR, AlRahin EA, et al. Prevalence of anosmia or ageusia in patients with COVID-19 among United Arab Emirates population. Int Dent J. 2022;72(2):249–256. doi:10.1016/j.identj.2021.05.006

24. Boscolo-Rizzo P, Borsetto D, Fabbris C, et al. Evolution of altered sense of smell or taste in patients with mildly symptomatic COVID-19. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;146(8):729–732. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2020.1379

25. Tipnis SR, Hooper NM, Hyde R, et al. A human homolog of angiotensin-converting enzyme. Cloning and functional expression as a captopril-insensitive carboxypeptidase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(43):33238–33243. doi:10.1074/jbc.M002615200

26. Butowt R, Bilinska K, Von Bartheld CS. Chemosensory dysfunction in COVID-19: integration of genetic and epidemiological data points to D614G spike protein variant as a contributing factor. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2020;11(20):3180–3184. doi:10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00596

27. Sorokowski P, Karwowski M, Misiak M, et al. Sex differences in human olfaction: a meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2019;10:242. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00242

28. Tong JY, Wong A, Zhu D, et al. The prevalence of olfactory and gustatory dysfunction in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;163(1):3–11. doi:10.1177/0194599820926473

29. Netland J, Meyerholz DK, Moore S, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection causes neuronal death in the absence of encephalitis in mice transgenic for human ACE2. J Virol. 2008;82(15):7264–7275. doi:10.1128/jvi.00737-08

30. Gu J, Gong E, Zhang B, et al. Multiple organ infection and the pathogenesis of SARS. J Exp Med. 2005;202(3):415–424. doi:10.1084/jem.20050828

31. Li YC, Bai WZ, Hashikawa T. The neuroinvasive potential of SARS-CoV2 may play a role in the respiratory failure of COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol. 2020;92(6):552–555. doi:10.1002/jmv.25728

32. Subramanian A, Nirantharakumar K, Hughes S, et al. Symptoms and risk factors for long COVID in non-hospitalized adults. Nat Med. 2022;28(8):1706–1714. doi:10.1038/s41591-022-01909-w

33. Glennon SG, Huedo-Medina T, Rawal S, et al. Chronic cigarette smoking associates directly and indirectly with self-reported olfactory alterations: analysis of the 2011–2014 national health and nutrition examination survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21(6):818–827. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntx242

34. Rashid RA, Zgair A, Al-Ani RM. Effect of nasal corticosteroid in the treatment of anosmia due to COVID-19: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled study. Am J Otolaryngol. 2021;42(5):103033. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2021.103033

35. Paleiron N, Mayet A, Marbac V, et al. Impact of tobacco smoking on the risk of COVID-19: a large scale retrospective cohort study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2021;23(8):1398–1404. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntab004

36. Tarifi A, Al Shdaifat AA, Al-Shudifat AM, et al. Clinical, sinonasal, and long-term smell and taste outcomes in mildly symptomatic COVID-19 patients. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75(7):e14260. doi:10.1111/ijcp.14260

37. Rashid RA, Alaqeedy AA, Al-Ani RM. Parosmia due to COVID-19 disease: a 268 case series. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;74(Suppl2):2970–2977. doi:10.1007/s12070-021-02630-9

38. Lucidi D, Molinari G, Silvestri M, et al. Patient-reported olfactory recovery after SARS-CoV-2 infection: a 6-month follow-up study. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2021;11(8):1249–1252. doi:10.1002/alr.22775

39. Coelho DH, Reiter ER, Budd SG, et al. Quality of life and safety impact of COVID-19 associated smell and taste disturbances. Am J Otolaryngol. 2021;42(4):103001. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2021.103001

40. Saniasiaya J, Prepageran N. Impact of olfactory dysfunction on quality of life in coronavirus disease 2019 patients: a systematic review. J Laryngol Otol. 2021;135(11):947–952. doi:10.1017/s0022215121002279

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.