Back to Journals » International Journal of General Medicine » Volume 15

Too Much, Too Mild, Too Early: Diagnosing the Excessive Expansion of Diagnoses

Authors Hofmann B

Received 29 March 2022

Accepted for publication 13 June 2022

Published 6 August 2022 Volume 2022:15 Pages 6441—6450

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S368541

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Bjørn Hofmann1,2

1Institute for the Health Sciences, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Gjøvik, Norway; 2The Centre of Medical Ethics, Faculty of Medicine, the University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

Correspondence: Bjørn Hofmann, Institute for the Health Sciences, The Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), PO Box 191, N-2801, Gjøvik, Norway, Email [email protected]

Abstract: Tremendous scientific and technological advances have vastly improved diagnostics. At the same time, false alarms, overdiagnosis, medicalization, and overdetection have emerged as pervasive challenges undermining the quality of healthcare and sustainable clinical practice. Despite much attention, there is no clarity on the classification and handling of excessive diagnoses. This article identifies three basic types of excessive diagnosing: too much, too mild, and too early. Correspondingly, it suggests three ways to reduce excess and advance high value care: we must stop diagnosing new phenomena, mild conditions, and early signs that do not give pain, dysfunction, and suffering.

Keywords: diagnosis, overdiagnoses, overtreatment, expansion, excess

Introduction

Due to tremendous scientific and technological advances, there have been vast expansions in the number of diagnoses. From John Graunt’s Bills of Mortality in 1665 till ICD-11,1 DSM-5,2 ICPC-2,3 and in ICF4 more people are diagnosed with more diseases than ever before. Figure 1 shows the expansion of number of diagnostic codes from ICD-1 in 1900 till ICD-11 in 2018.

|

Figure 1 Expansion in the number of diagnoses in the International Classification of Disease (ICD). |

Part of this expansion stems from an ample increase in knowledge about bodily, behavioural, and mental mechanisms. By differentiating existing diagnoses in more precise and actionable entities, more people can be helped - better and earlier than ever before.

However, our diagnostic capacities by far outrun our abilities to help. Not only do we lack curative measures for all diagnoses, but the many diagnostic technologies also come with errors,5 and we come to diagnose when it does not help people. While we can detect many more phenomena than ever before, we lack knowledge of whether they represent or predict anything that is clinically relevant, such as pain, dysfunction, and suffering.6 Medicine has expanded its taxonomies from descriptions of experienced and manifest disease to indicators (eg, biomarkers), risk factors (eg, hypertension),7 social phenomena (eg, behaviour), aesthetic phenomena (eg, look), and many non-harmful conditions.

The growth in diagnoses has been described as a “diagnostic inflation”,8–12 “diagnostic expansion”,13–19 and “diagnostic creep”20–23 and has been characterized by concepts, such as medicalization (over-, bio-),24 overdiagnosis,25 overdetection, overdefinition,26 misclassification, maldetection,27 disease mongering28 etc.

While the vast expansion of diagnoses appears to be haunted by complex causes and conceptual confusion, it is embodied by three basic phenomena: too much, too mild, and too early. The first represents an expansion of diagnoses by including new phenomena, the second is an extension by degrees, and the latter is a temporal expansion. Table 1 provides an overview of the three types of excessive expansion of diagnoses.

|

Table 1 Overview of the Three Types of Excessive Expansion of Diagnoses: Too Much, Too Mild, and Too Early |

Before scrutinizing these three types of expansion of diagnoses, it is important to acknowledge the manifold function of diagnoses and their complex role in medicine and in society at large. For health professionals, diagnoses are crucial for forming a conceptual framework, to coordinate communication, and to guide actions.29 For the health care system, they are key for the organization of activities, institutions, and departments. For society diagnoses are fundamental to ensure justice, as diagnoses are used to attribute rights (to care) and free from obligations (work) as well as attributing accountability (eg, with respect to legal (in)sanity). For patients diagnoses are essential to understand one’s situation, adjust one’s aspirations, explain the situation to others, and to get access to attention, treatment, and care from health professionals.29 Hence, diagnoses involve a range of norms and values for a wide variety of stakeholders in great many contexts. Accordingly, they do very much good for individuals, professionals, and for societies at large. In this article, however, I focus on the less good aspects of expanding diagnoses. The aim is to enhance the good side of diagnoses (expansion) by avoiding the bad ones, ie, to improve the health care in one of its crucial activities for helping individuals: diagnostics.

Three Types of Excess: Too Much, Too Mild, and Too Early Diagnosis

In the case of too much diagnosis we tend to label phenomena that have not been diagnosed before. This can be a) ordinary life experiences, such as loneliness or grief, b) social phenomena, such as school behavior in children (ADHD)45 or c) biomedical phenomena, such as elevated blood pressure, obesity or measurable risk factors. While expanding diagnoses by including new phenomena can be warranted and welcome, it does not always benefit the persons and can be harmful, ie, it is too much. Certainly, it can be difficult to decide what is beneficial and what is harmful, and there may be different perspectives on the benefit-to-harm balance amongst patients, proxies, patient organizations, professionals, and health policy makers. Nevertheless, we need to focus on when we get too much diagnosis.

Diagnoses may also be unduly expanded by lowering the detection threshold beyond what benefits the person, ie, being too mild. By including milder cases in the definition of the disease or in its diagnostic criteria, people can be diagnosed with diseases that may not bother them. Gestational diabetes and chronic kidney disease may serve as examples.30 While detecting and treating milder cases may appear successful, many of the subsequent treatments may not benefit the persons. They would have lived with the condition without experiencing it.

Excessive expansion of diagnoses may also occur by diagnosing too early, ie, by temporal expansion. This happens when we diagnose abnormalities that are not going to cause harm by disease (in terms of pain, dysfunction, suffering) in the future. This can be precursors of disease that do not develop into disease, such as cases of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) or indolent lesion of epithelial origin (IDLE).31

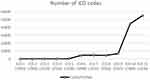

Figure 2 illustrates how diagnoses can be too mild and too early related to wellbeing and suffering over time.

Why is It Bad?

The problems with the three types of expansion are somewhat different. In the case of too much diagnosis we can digress responsibility and divert from more efficient measures, eg, when we make ordinary life experiences, such as grief and loneliness, or social phenomena, such as school behavior, diagnoses. Some such phenomena may be better dealt with outside the healthcare system, eg, by families and friends.

Moreover, we may also do too much diagnosing of biomedical phenomena when they are not experienced in terms of pain, dysfunction, or suffering. Mild hypertension or hyperglycemia, or various risk factors, such as obesity, are most often not experienced as painful or dysfunctional, but treating them can introduce potential harms from diagnostics and treatment. Headache, dizziness, constipation, diarrhea, muscle pain, fatigue, sleep problems, and low blood platelet count from statin use is but one example of the latter. Moreover, getting a diagnosis can reduce the quality of life and cause anxiety and stigma.29,32

In sum, we can do wrong when we diagnose too much when applying inappropriate labels and treatments, when diverting from more efficient measures, and when inciting harms from diagnostics and treatment.

In the case of too mild diagnosis, we inflate diagnosis by including phenomena that are too mild to cause any pain, dysfunction, or suffering or where the treatment results in more harm than benefit. In such cases we provide unnecessary treatment and introduce potential harm both from diagnostics and treatment.

Too early diagnosis results in overdiagnosis and overtreatment and potential harm from both. The cases that we detect and treat, would never have caused the person any problems. Hence, we violate the ethical principles of non-maleficence and beneficence. Additionally, we drain resources from alternative health care services (justice) and patients do not know that they are overdiagnosed and overtreated (autonomy). The problem is that it is (yet) difficult to predict whether a detected condition will develop into something that causes pain, dysfunction, or suffering.33

Basic Differences and Overlaps Between the Types of Diagnostic Expansion

Too much, too mild, and too early represent different types of unwarranted expansion of diagnoses. The first is an expansion of phenomena in the world to be included in diagnoses. This is an ontological expansion. This corresponds to what has been called a “horizontal expansion” in the framework of concept creep, as more cases are included “horizontally”.20

In the case of too mild diagnosis, we lower the detection threshold value so that milder cases are included. In doing so we change the norms that decide which cases fall under the concept of a particular diagnosis. Thus, this is a normative-conceptual expansion, and resembles “vertical expansion” in concept creep, as milder cases are included.20

In the case of too early diagnosis, we detect and treat conditions that we do not know whether will develop into disease and cause pain, dysfunction, and suffering in the future. Accordingly, this is an expansion into the unknown future, ie, an epistemic-temporal expansion.33

What can cause confusion is the fact that we have combinations of these expansions. For example, we can diagnose biomedical phenomena that are not experienced, and which will not develop to experienced disease in the future, such as various precursors of disease. Then we detect too much and too early.

Correspondingly, we can diagnose mild conditions that will not develop to experienced disease in the future, like in the case with hypertension or hyperglycemia. Such expansions are too mild and too early. Notably, they are both overdetection, as they detect mild cases that do not bother the person here and now, and overdiagnosis, as they may not cause any problems to the person in the future.

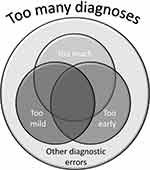

The important difference between too mild and too early diagnosis is whether the disease is occurring here and now or in the future. Figure 3 illustrates cases of too much, too mild, and too early diagnoses.

|

Figure 3 Illustration of cases where there would have been too much, too mild, and too early diagnosis compoared to a case where early diagnosis would have been appropriate. |

Too Many Diagnoses

Too much, too mild, and too early are three roads to diagnostic inflation and too many diagnoses. For example, changing the definition of osteoporosis from bone mineral density T-score cut-off to National Osteoporosis Foundation 2008 guideline, the prevalence increased from 21% to 72% in US women >65 years.34 Altering the definition of prediabetes from impaired fasting glucose to the American Diabetes Association 2010 criteria increased the prevalence from 26% to 50% in Chinese adults >18 years.34

There are of course also other sources of too many diagnoses. False positive test results can result in wrong diagnoses. Incidental findings of uncertain significance can be either too much or too mild, if they are of inexperienced or irrelevant phenomena, or too early if they will not develop into something experienced. Hence, there are many roads to excess, and differentiating between them is crucial for addressing their problems. Figure 4 illustrates the relationship between the three types of diagnoses expansion.

|

Figure 4 Illustration of the relationship between the three types of diagnoses expansion including other diagnostic errors. |

Maldetection, Misclassification, Overdetection, and Overdefinition

The many attempts to address the multiple ways that diagnoses can expand excessively have created a wide range of specific concepts, and created some confusion, for example between concepts, such as maldetection, misclassification, overdetection, and overdefinition. Diagnosing “abnormalities” that are not going to cause harm, have been called “maldetection overdiagnosis”27 and “overdetection overdiagnosis”.35 These are cases of too early diagnosis. Moreover, diagnosing too mild cases has been called “misclassification overdiagnosis”27 and “overdefinition overdiagnosis”.35 However, the latter includes risk factors, which is a case of including too much. Others have counted maldetection and misclassification out of overdiagnosis and consider them to be causes of overdiagnosis.25

Hence, there is little agreement on the conceptual framework for addressing too many diagnoses. Focusing on the basic phenomena too much, too mild, and too early can make it easier to identify and address the basic problems with excessive diagnoses. Furthermore, it can make it simpler to acknowledge what they have in common: they do not help professionals in reducing pain, dysfunction, and suffering in individual persons because they address the wrong phenomena, too mild conditions, and/or diagnose too early.

Targeting Too Many Diagnoses

The analysis of the three types of diagnostic inflation provides directions for targeting their problems.

In order to avoid too much diagnosis, we must prevent labelling phenomena that cannot be clearly connected to human pain, dysfunction, or suffering with medical diagnostic labels as labelling can have a wide range of negative effects.36 Hence, we may do more harm than good. Moreover, we must be careful with applying medical labels where medical means are not helpful compared to other approaches. That is not to say that labelling is bad. As pointed out, medical labelling is conceptually and practically essential to medicine. However, medical labelling is directed at helping people, and if our labelling goes beyond what can be connected to pain, dysfunction, or suffering, there is a danger of overdoing. Correspondingly, medically detectable pain, dysfunction, or suffering may be better managed by non-medical means (however they are defined). In such cases we need to reflect on why we need medical instead of non-medical categories, as they can do more harm than good.36

Correspondingly, we must stop diagnosing conditions that are too mild to be of any relevance in terms of reducing pain, dysfunction, or suffering. The point is not to abandon all preventive measures, but only that we must avoid lowering diagnostic thresholds beyond what is helpful to persons. Moreover, we need to inform people well when we are uncertain about who will be helped. Certainly, when we know or have good reasons to believe that a specific condition will aggravate to something that will cause pain, dysfunction, or suffering, we should target the condition as early and as efficiently as possible (carefully balancing the potential risks against the benefits, of course).

Likewise, we must avoid detecting abnormal conditions too early, ie, when it is not helpful in avoiding experienced disease. Clearly, it can be very valuable to detect abnormal conditions early, but we should refrain from doing so when it does not avoid or reduce the burden of disease. This is certainly no easy task, but the task should not be evaded.

Moreover, we must have open discussions on the trade-offs between too early and too late and between too mild and too early. In particular, we should provide evidence to facilitate individual informed choice.

There are many measures to avoid unwarranted expansion of diagnoses. Table 2 provides an overview and indicates how the various measures address the three types of excessive diagnose expansion.

|

Table 2 Measures to Avoid Unwarranted Expansion of Diagnoses with Indications of Which Type of Expansion They Address. Darker Shading Indicates That the Measure Addresses the Expansion Better |

There are of course other related measures that are relevant for reducing overactivity in health care, such as deprescribing,37 deimplementation,38 decommissioning,39 disinvestment40,41 that are helpful in avoiding too much diagnoses. However, they do not address the other kinds of excessive diagnoses in any particular way.

Appropriate Expansion of Diagnoses

As pointed out in the introduction, diagnoses have many important functions and expanding them can benefit patients, proxies, health professionals, health services managers, and society in many ways. These aspects are well covered in the general literature. The objective in this article has been to address the cases where the expansion of diagnoses is not appropriate. The goal hereby has not been to undermine or downplay the very good aspects of diagnoses and their expansion. On the contrary, it has been to avoid its side-effects, to foster patient safety (by reduced unwarranted diagnoses) and autonomy (by making them better informed), to promote professional integrity (by improving diagnostic competencies), and to maintain trust in medicine and healthcare. In sum, reducing unwarranted expansion of diagnoses is crucial for improving the health care in one of its crucial activities in helping individuals: diagnostics.

Conclusion

There are three types of excessive diagnosing: too much, too mild, and too early. They can result in overdiagnosis and overtreatment, harms from diagnostics and unnecessary treatment, anxiety and stigma, as well as diversion from more efficient measures and responsibilities. To halt excessive diagnosing, we must stop diagnosing a) phenomena, b) mild conditions, and c) early signs that do not give pain, dysfunction, and/or suffering. When faced with uncertainty of risks and benefits of diagnosing, or when trading off between present risks and future benefits, we need to provide good evidence and inform potential beneficiaries. To further high-quality care and sustainable clinical practice we must bar the unwarranted expansion of diagnoses.

Key Points

- Excessive diagnosing hampers the advancement of high value care and sustainable clinical practice

- Excessive diagnosing can result in overdiagnosis and overtreatment, harms from unnecessary diagnostics and treatment, medicalization, anxiety, and stigma, as well as diversion from more efficient measures and responsibilities

- To avoid conceptual confusion, we need to address three generic types of excessive diagnosis:

- too much: including too many phenomena

- too mild: setting the thresholds too low

- too early: including conditions that will never bother the person● To stop excessive diagnosing and advance high value care we must stop diagnosing a) phenomena, b) mild conditions, and c) early signs that do not give pain, dysfunction, and suffering

Author Contributions

I am the sole author of this manuscript. I have made all contributions to the work reported, both is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

Part of the study is funded by the Norwegian Research Council: Grant number 302503 (IROS).

Disclosure

I certify that there is no conflict of interest in relation to this manuscript, and there are no financial arrangements or arrangements with respect to the content of this manuscript with any companies or organizations.

References

1. World Health Organization. ICD-11 implementation or transition guide. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019.

2. Kawa S, Giordano J. A brief historicity of the Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: issues and implications for the future of psychiatric canon and practice. Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2012;7(1):2. doi:10.1186/1747-5341-7-2

3. World Organization of Family Doctors (WONCA) International Classification Committee. International Classification of Primary Care, ICPC-2; 1998.

4. World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001.

5. McGlynn EA, McDonald KM, Cassel CK. Measurement is essential for improving diagnosis and reducing diagnostic error: a report from the institute of medicine. JAMA. 2015;314(23):2501–2502. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.13453

6. Hofmann BM. Back to basics: overdiagnosis is about unwarranted diagnosis. Am J Epidemiol. 2019;188(10):1812–1817. doi:10.1093/aje/kwz148

7. Schwartz PH. Risk and disease. Perspect Biol Med. 2008;51(3):320–334. doi:10.1353/pbm.0.0027

8. Batstra L, Frances A. Diagnostic inflation: causes and a suggested cure. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2012;200(6):474–479. doi:10.1097/NMD.0b013e318257c4a2

9. Batstra L, Frances A. Holding the line against diagnostic inflation in psychiatry. Psychother Psychosom. 2012;81(1):5–10. doi:10.1159/000331565

10. Fabiano F, Haslam N. Diagnostic inflation in the DSM: a meta-analysis of changes in the stringency of psychiatric diagnosis from DSM-III to DSM-5. Clin Psychol Rev. 2020;80:101889. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101889

11. Frances A. Diagnostic inflation can be bad for our patients’ heath. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58(10):567–569.

12. Kudlow P. The perils of diagnostic inflation. CMAJ. 2013;185(1):E25–E6. doi:10.1503/cmaj.109-4371

13. Horwitz AV, Wakefield JC. The expansion of post-traumatic stress disorder: some issues regarding diagnosis and treatment. MD Advis. 2011;4(1):6–10.

14. Nishikawa G, Prasad V. Diagnostic expansion in clinical trials: myocardial infarction, stroke, cancer recurrence, and metastases may not be the hard endpoints you thought they were. BMJ. 2018;362. doi:10.1136/bmj.k3783

15. Phillips J. Guilty of diagnostic expansion. BMJ. 2013;346:f2254.

16. Copp T, Jansen J, Doust J, Mol BW, Dokras A, McCaffery K. Are expanding disease definitions unnecessarily labelling women with polycystic ovary syndrome? BMJ. 2017;358:j3694. doi:10.1136/bmj.j3694

17. Kaplan RM. Disease, Diagnoses, and Dollars: Facing the Ever-Expanding Market for Medical Care. Springer Science & Business Media; 2009.

18. Lane R. Expanding boundaries in psychiatry: uncertainty in the context of diagnosis‐seeking and negotiation. Sociol Health Illn. 2020;42(S1):69–83. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.13044

19. Moynihan R, Glassock R, Doust J. Chronic kidney disease controversy: how expanding definitions are unnecessarily labelling many people as diseased. BMJ. 2013;347(jul29 3):f4298. doi:10.1136/bmj.f4298

20. Haslam N. Concept creep: psychology’s expanding concepts of harm and pathology. Psychol Inq. 2016;27(1):1–17. doi:10.1080/1047840X.2016.1082418

21. Scott MJ. Overstating preventative capacity and diagnostic creep. In: Towards a Mental Health System That Works. Routledge; 2016:25–28.

22. George DR, Whitehouse PJ. (Un) Ethical early interventions in the Alzheimer’s “Marketplace of Memory”. AJOB Neurosci. 2021;12(4):245–247. doi:10.1080/21507740.2021.1941402

23. Jacob K. Idioms of distress, mental symptoms, syndromes, disorders and transdiagnostic approaches. Asian J Psychiatr. 2019;46:7–8. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2019.09.018

24. Hofmann B. Medicalization and overdiagnosis: different but alike. Med Health Care Philos. 2016;19(2):253–264. doi:10.1007/s11019-016-9693-6

25. Davies L, Petitti DB, Martin L, Woo M, Lin JS. Defining, estimating, and communicating overdiagnosis in cancer screening. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(1):36–43. doi:10.7326/M18-0694

26. Thombs BD, Turner KA, Shrier I. Defining and evaluating overdiagnosis in mental health: a meta-research review. Psychother Psychosom. 2019;88(4):193–202. doi:10.1159/000501647

27. Rogers WA, Mintzker Y. Getting clearer on overdiagnosis. J Eval Clin Pract. 2016;22(4):580–587. doi:10.1111/jep.12556

28. Doran E, Henry D. Disease mongering: expanding the boundaries of treatable disease. Intern Med J. 2008;38(11):858–861. doi:10.1111/j.1445-5994.2008.01814.x

29. Hofmann B. Acknowledging and addressing the many ethical aspects of disease. Patient Educ Couns. 2022;105(5):1201–1208. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2021.09.015

30. Moynihan R, Brodersen J, Heath I, et al. Reforming disease definitions: a new primary care led, people-centred approach. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2019;24(5):170–173. doi:10.1136/bmjebm-2018-111148

31. Esserman LJ, Thompson IM, Reid B, et al. Addressing overdiagnosis and overtreatment in cancer: a prescription for change. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(6):e234–e42. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70598-9

32. Jørgensen P, Langhammer A, Krokstad S, Forsmo S. Is there an association between disease ignorance and self-rated health? The HUNT Study, a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2014;4(5):e004962. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-004962

33. Hofmann B. Diagnosing overdiagnosis: conceptual challenges and suggested solutions. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29(9):599–604. doi:10.1007/s10654-014-9920-5

34. Doust J, Vandvik PO, Qaseem A, et al. Guidance for modifying the definition of diseases: a checklist. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(7):1020–1025. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1302

35. Brodersen J, Schwartz LM, Heneghan C, O’Sullivan JW, Aronson JK, Woloshin S. Overdiagnosis: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2018;23(1):1–3. doi:10.1136/ebmed-2017-110886

36. Sims R, Michaleff ZA, Glasziou P, Thomas R. Consequences of a diagnostic label: a systematic scoping review and thematic framework. Front Public Health. 2021;9:2111. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.725877

37. Sawan M, Reeve E, Turner J, et al. A systems approach to identifying the challenges of implementing deprescribing in older adults across different health-care settings and countries: a narrative review. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2020;13(3):233–245. doi:10.1080/17512433.2020.1730812

38. Wolf ER, Krist AH, Schroeder AR. Deimplementation in pediatrics: past, present, and future. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;175(3):230–232.

39. Williams I, Harlock J, Robert G, Mannion R, Brearley S, Hall K. Health services and delivery research. Decommissioning health care: identifying best practice through primary and secondary research – a prospective mixed-methods study. Health Serv Deliv Res. 2017;5(22):1–194. doi:10.3310/hsdr05220

40. Elshaug AG, Hiller JE, Tunis SR, Moss JR. Challenges in Australian policy processes for disinvestment from existing, ineffective health care practices. Aust New Zealand Health Policy. 2007;4(1):23. doi:10.1186/1743-8462-4-23

41. Orso M, de Waure C, Abraha I, et al. Health technology disinvestment worldwide: overview of programs and possible determinants. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2017;33(2):239–250. doi:10.1017/S0266462317000514

42. Lea M, Hofmann BM. Dediagnosing – a novel framework for making people less ill. Eur J Intern Med. 2021;95:17–23. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2021.07.011

43. Sistrom CL. The ACR appropriateness criteria: translation to practice and research. J Am Coll Radiol. 2005;2(1):61–67. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2004.07.003

44. Page A, Etherton-Beer C. Undiagnosing to prevent overprescribing. Maturitas. 2019;123:67–72. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2019.02.010

45. Conrad, P. & Potter, D. (2000). From Hyperactive Children to ADHD Adults: Observations of the Expansion of Medical Categories. Social Problems, 47(4), 559–582

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.