Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

The Silver Lining of Perceived Overqualification: Examining the Nexus Between Perceived Overqualification, Career Self-Efficacy and Career Commitment

Authors Deng Y

Received 22 May 2023

Accepted for publication 3 July 2023

Published 17 July 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 2681—2694

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S420320

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Mei-Chun Cheung

Yu Deng

School of Educational Science, Zhaotong University, Zhaotong, 657000, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Yu Deng, Email [email protected]

Aim: This study aimed to investigate how perceived overqualification is linked to an individual’s career commitment among service sector employees in China. Additionally, it sought to examine the mediating role of career self-efficacy and the moderating effect of social support.

Methods: This study collected data from 441 employees using a three-wave data collection design with a two-week gap between each round. Moreover, we employed partial least square structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) to analyze the data.

Results: The findings asserted that perceived overqualification was positively associated with employee career self-efficacy and commitment. Furthermore, career self-efficacy mediated the link between perceived overqualification and career commitment. The study also demonstrated that perceived overqualification and career self-efficacy were influenced by the level of social support received, with a stronger relationship observed when social support was high. These findings highlight the value of fostering social support and career self-efficacy among coworkers to increase overqualified employees’ commitment to their careers and provide valuable insights for organizations seeking to manage their talent pool effectively.

Discussion: The study suggests that when employees perceive themselves as overqualified for their job, it can lead to a higher sense of career self-efficacy, which is the belief in one’s ability to perform job tasks effectively. This increased self-efficacy, in turn, can lead to a greater commitment to their career. Furthermore, fostering social support and building career self-efficacy can help organizations manage their overqualified pool effectively and improve employee satisfaction and productivity.

Keywords: perceived overqualification, career self-efficacy, social support, career commitment

Introduction

The worldwide economic slowdown and the sluggishness of job markets have resulted in an increasing number of employees whose education, expertise, and experience exceed the requirements of their current job roles.1 The prevalence of this phenomenon has escalated in recent years owing to numerous factors, including economic transformations, shifts in the labor market, and a surplus of professionals with overqualification. As a result, overqualified individuals may accept jobs below their qualification level to maintain financial stability.2 Overqualification refers to employees being placed in positions that do not utilize their educational qualifications, experience, and skill sets. When employees perceive themselves as overqualified for their current position, it can lead to negative job attitudes, reduced job satisfaction, and decreased commitment to the organization.3 However, there can also be positive outcomes of overqualification. Employees who perceive themselves as overqualified may possess higher knowledge and skills, which can benefit their organization in the long run. Additionally, they may be more adaptable to changing job demands and possess greater potential for career advancement within the organization.4

However, the relationship between overqualification and career progression remains a subject of debate, with some studies suggesting that overqualified employees possess valuable skills and experience that can aid in upward mobility.3,5 Overqualified employees may leverage their excess qualifications to seek new challenges, excel in their roles, and enhance their career growth.6 However, this study focuses on how overqualification affects an individual’s level of career commitment. Previous studies asserted that overqualified employees are more resilient and adaptable in the face of change,7 which could positively influence their career commitment - The degree to which work is integrated into an individual’s life plan and their desire to continue working in their chosen career, even if they could earn money without working.8,9 Grasping the impact of POQ on career commitment is essential, as overqualified employees bring valuable skills and knowledge that could be more effectively employed. If POQ positively affects their career commitment, it could lead to potential benefits for both the individual and their organization. Examining the relationship between POQ and career commitment can aid researchers and organizations in comprehending how to effectively support and engage overqualified employees, maximizing their potential and preventing the negative consequences of underutilized talent.4,10

Empirical studies have demonstrated a favorable association between career self-efficacy and career commitment. Overqualified individuals with elevated levels of career self-efficacy exhibit a more substantial commitment to their career path due to their heightened confidence in their ability to achieve success.11,12 In addition, prior research has proposed that the existing ambiguity in the literature concerning the association between POQ and career commitment could be ascribed to career self-efficacy - confidence in one’s abilities to succeed in one’s chosen profession.13 Overqualified individuals with a strong sense of career self-efficacy are more inclined to view their present employment as a means to advance toward their envisioned career path. They may believe they can overcome any challenges or obstacles and may be more motivated to invest in their current job to build the skills and experience they need to achieve their career goals.14,15

Furthermore, this study uncovered a critical component that mitigates the indirect influence of the link between POQ and career commitment, in addition to studying the variables that underlie this relationship. This suggests how certain factors may moderate the relationship between POQ and its effects on career commitment via career self-efficacy. According to previous studies, social support is crucial for individuals in various aspects of their lives, including personal and professional lives.16 In the workplace, social support can play a critical role in helping employees to navigate the challenges of their job, maintain a positive outlook, and achieve their career goals.17 Earlier research has proposed that social support can act as a protective factor against the detrimental impact of POQn on an individual’s well-being and job satisfaction. Likewise, social support strengthens the relationship between POQ and an individual’s career commitment via career self-efficacy.18,19

Our study model (see Figure 1), adds three significant insights to the current literature. First, it addresses the gap in previous studies by focusing on theory-based investigations that elucidate the circumstances, mechanisms, and reasons for which overqualified employees display certain favorable career results. This lack of attention has resulted in a gap in our theoretical understanding. Prior research has neglected the potential positive consequences of perceived overqualification.3 The connection between perceived overqualification and career commitment has not received significant research attention. To bridge this gap, our study adopts a distinctive perspective by conceptualizing the mechanisms that provide various theoretical justifications for the association between POQ and career commitment. This approach sets our research apart from previous studies that concentrate solely on one aspect of POQ.20

|

Figure 1 Theoretical framework. |

Second, our study enriches the literature by emphasizing career self-efficacy as a mediator. This emphasis enables us to understand better the psychological mechanisms underpinning the association between perceived overqualification and career commitment. Such insights can inform the creation of strategies and interventions to enhance employees’ career self-efficacy and reinforce the benefits of perceived overqualification on career commitment. Employees who believe they are overqualified may also have higher levels of career self-efficacy, which might increase their dedication to their jobs. Third, the study’s findings advance the literature that social support plays a crucial role in shaping how overqualified employees perceive their situation and career self-efficacy. When an overqualified employee feels supported by colleagues, they may have a more positive view of their job and believe in their ability to perform well in their current position. The implications of these findings are significant for organizations that want to retain and engage their talented employees. By promoting a culture of social support and providing opportunities for employees to build relationships with their colleagues, organizations can help their overqualified employees feel more connected to their jobs and committed to their careers.

Hypotheses Development

POQ and Career Commitment

Prior research has suggested that overqualification can stimulate employees to apply their skills and knowledge in novel ways, resulting in heightened engagement and commitment.21 Overqualified employees may find creative and resourceful ways to apply their skills and knowledge within their current job responsibilities. By identifying and capitalizing on opportunities to utilize their expertise, such employees can potentially increase their job satisfaction, which can positively impact their career commitment.22 Overqualification can catalyze employees to seek new organizational challenges, ultimately contributing to their professional growth and development.23 Additionally, overqualified employees can view their current situation as an opportunity to better understand their organization and industry.24 This can help them develop a more comprehensive perspective on their career, allowing them to make more informed decisions about their professional development and future goals. This may increase their commitment to their career by providing a more straightforward path to advancement.11

Being overqualified can provide a chance to take on more challenging and complex work, leading to personal and professional growth. In addition, this approach may enable overqualified individuals to acquire new skills and experience beyond their typical area of expertise. Indeed, gaining new skills and diverse experience can broaden their career prospects and augment their versatility in the job market.25 Individuals who feel overqualified may seek additional responsibilities and challenges outside their job description,26 which allow them to develop new skills, expand their knowledge base, and take on leadership roles. Consequently, they may experience greater job satisfaction and demonstrate a stronger commitment to their career and organization.27 Perceived overqualification can also lead to a sense of mastery and accomplishment. When individuals can complete tasks above their job requirements, they may feel a sense of pride and confidence in their abilities and increase their motivation and commitment to their career.22 Perceived overqualification can provide individuals with a sense of security and stability. Suppose they believe their skills and experience exceed their job requirements. In that case, they may feel more confident in finding another job if needed by reducing their anxiety and increasing their commitment to their job and organization.5,28

Moreover, overqualified employees may leverage their skills and knowledge to mentor and support colleagues,18 contribute to a positive work environment, and help these employees feel valued and engaged in their current roles. This sense of purpose can promote career commitment, as they feel they are making a meaningful contribution to their organization.29,30 Person-Job Fit theory suggests that overqualified employees experience positive effects on career commitment and find ways to improve their fit within their current position. By actively seeking opportunities to use their skills, contribute to their organization, and grow professionally, overqualified employees can enhance their job satisfaction and engagement, ultimately leading to increased career commitment.21

Hypothesis 1: POQ is positively related to career commitment

POQ, Career Self-Efficacy, and Career Commitment

Career self-efficacy pertains to an individual’s confidence in their capability to perform effectively and accomplish their career objectives.31 Career self-efficacy shapes employees’ career decisions, motivation, and commitment.32 Career self-efficacy can act as a key factor between POQ and career commitment by helping overqualified employees to view their situation as an opportunity for growth rather than a barrier.33 According to the person-job fit theory, the degree of alignment between an individual’s skills, abilities, and personality and the characteristics of their job directly influences their level of job satisfaction, engagement, and career commitment.34 When overqualified employees maintain or improve their career self-efficacy, they are more likely to seek ways to enhance this fit, leading to positive outcomes.35 Overqualified employees with high career self-efficacy may proactively seek ways to utilize their skills and knowledge within their current roles, finding creative solutions to challenges and taking on additional responsibilities. Career self-efficacy can enhance job satisfaction, imbue individuals with a stronger sense of purpose, and thus, bolster their level of career commitment.36,37

Overqualified employees possessing high levels of career self-efficacy are more likely to engage in continuous professional development as they have confidence in their ability to thrive in their chosen profession. By pursuing training, certifications, or further education, overqualified employees can expand their skill set and increase their value within the organization, positively impacting their career commitment.38 Overqualified employees with high career self-efficacy may recognize the value of networking and mentoring relationships in their professional growth.39 By connecting with others in their field and sharing their expertise, they can create a support system that encourages career commitment and fosters professional development.40

Employees with a robust sense of career self-efficacy are more prone to display adaptability and resilience in response to perceived overqualification. Instead of feeling stuck or limited in their current role, they may view the situation as an opportunity to learn, grow, and expand their capabilities.41 This adaptable mindset can positively influence career commitment, as employees remain dedicated to their profession despite challenges. Career self-efficacy can mediate between perceived overqualification and career commitment by encouraging employees to utilize their skills, engage in professional development, build supportive networks, and display adaptability and resilience.24 By emphasizing these aspects, employees who feel overqualified can increase their career commitment and transform the experience of perceived overqualification into an opportunity for professional growth and achievement.42

Hypothesis 2: POQ is positively related to career self-efficacy Hypothesis 3: The link between perceived overqualification and career commitment is mediated by career self-efficacy

Social Support as a Moderator

When employees receive strong social support from colleagues, supervisors, friends, and family, the effects of POQ on career self-efficacy can be mitigated.18 Social support can provide emotional reassurance, helping overqualified employees cope with the stress and frustration of feeling overqualified.19,43 These employees may maintain or even improve their career self-efficacy by receiving empathy, understanding, and encouragement from their social network.44 Colleagues and supervisors can offer instrumental support through advice, information, or resources to help overqualified employees better utilize their skills and knowledge within their current job or explore new career opportunities. This type of support can bolster career self-efficacy by enabling employees to take action and make changes in their professional lives.45

Social support can also involve receiving positive feedback and validation from others, which can help overqualified employees maintain their confidence in their abilities and skills. This reinforcement can strengthen the impact of perceived overqualification on career self-efficacy, as employees are reassured that their qualifications are valued and recognized.46 Social support through networking and mentorship opportunities can help overqualified employees enhance their careers within their current organization or by pursuing new opportunities elsewhere.47,48 Networking can expose employees to new perspectives and insights, while mentorship can provide guidance and direction. These factors can contribute to maintaining or improving career self-efficacy.49 Furthermore, social support can moderate the path between perceived overqualification and career self-efficacy by providing various forms of support, such as emotional support, instrumental assistance, feedback and validation, and networking and mentorship opportunities.50 By receiving strong social support, overqualified employees may be better equipped to maintain or improve their career self-efficacy, mitigating the negative effects of POQ on their professional outlook and career decisions.24

Hypothesis 3: Social support moderates the relationship between POQ and career self-efficacy

Integrated Model

Social support can indirectly influence the positive relationship between POQ and career commitment by promoting career self-efficacy. By helping overqualified individuals recognize and leverage their unique skills and knowledge, social support can encourage them to embrace their career path with confidence and commitment. The fostering of career self-efficacy through social support can mediate the positive correlation between perceived overqualification and career commitment. Social support boosts the confidence of overqualified individuals in their career abilities by helping them see and utilize their skills and knowledge. Offering guidance and mentorship further strengthens their dedication to their career goals and encourages growth.

Hypothesis 3a: The extent to which career self-efficacy mediates the relationship between perceived overqualification and career commitment will be contingent on the level of social support. Specifically, the indirect effect of perceived overqualification on career commitment through career self-efficacy will be more pronounced when social support is high.

Methodology

Sample and Procedure

To validate the proposed hypotheses, this study utilized a survey methodology to collect data from employees in the service sector of China. A cover letter was also included on the first page of the questionnaire, clarifying that all information provided would be kept confidential and used solely for academic purposes. The online survey was disseminated through personal connections with employees from several service sector organizations located in China. Data collection for the study was conducted through a three-wave design, with a two-week gap between each round. This approach was adopted to ensure temporal separation between data collection for the perceived overqualification, social support (phase 1), and career self-efficacy (phase 2). In the third phase (phase 3), we collected data regarding employee career commitment. Data collection in three phases can help reduce the potential for common method bias (CMB).51 In the initial phase, 553 employees were contacted to collect data regarding employees demographics, perceived overqualification and social support. The authors received 523 responses after removing 3 questionnaires with missing values in the first phase. In the second phase, 511 respondents provided their input regarding career self-efficacy, and in the third and final wave, 492 respondents participated in rating their career commitment. Therefore, we retained 492 questionnaires for the study analysis after eliminating surveys with incomplete data, resulting in a response rate of 92.98%. In the final sample set, most participants (67%) were male, 89% had completed a university degree, and their respective organizations had employed 78% for over one year.

Measures

Perceived Overqualification (α = 0.91)

The nine-item scale developed by Maynard, Joseph, Maynard,52 were used to measure perceived overqualification. Sample item of the scale was “My job requires less education than I have.”

Career Commitment (α = 0.85)

Career commitment was measured with the four items scale developed by van der Heijden53 inspired by job-level measures.54 A sample item was: “I am prepared to engage in any type of personal sacrifice to advance my career.”

Career Self-Efficacy (α = 0.79)

Career self-efficacy was measured using the Career Decision-Making Self-efficacy Scale (CDMSE-SF) developed by Betz, Klein, Taylor.55 Example items include: “I am able to determine the steps to take if I am having academic trouble with an aspect of my chosen major.”

Social Support (α = 0.89)

The level of social support was assessed using an eight-question scale modified from the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS0.56 Sample items include: “There is a special person who is around when I am in trouble or in need”, “My family really tries to help me”.

Control Variable

Following earlier research,57,58 we incorporated workers’ age, gender, education, and length of service within the organization as control variables. Specifically, both age and organizational tenure were assessed in years, while gender was represented as a binary variable (0 = male, 1 = female).

Data Analysis

We used partial least square structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) to analyze the data collected for this study. The structural equation modeling (SEM) technique based on variance is commonly employed for analyzing multiple variables models.59 Our research model is quite intricate, which includes a mediator and a moderator to elucidate the pathways through which perceived overqualification affects career commitment. This type of exploratory research can take advantage of the flexibility in sample size and sampling distribution that PLS-SEM provides.60

Results

Descriptive Statistics

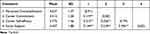

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients among study variables. The results showed a positive correlation between perceived overqualification and both career self-efficacy (r= 0.215, p < 0.01) and career commitment (r= 0.119, p < 0.01). Furthermore, the expected positive association between career self-efficacy and career commitment was evident, as evidenced by a significant positive correlation (r=0.396, p<0.01).

|

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics and Correlations |

Common Method and Non-Response Bias

To evaluate the credibility of the research and investigate potential non-response bias, we implemented Armstrong, Overton61 recommendation by analysing the reactions of the initial and final one hundred participants. To assess non-response biases, paired sample t-tests were carried out and the outcomes suggested that there was no statistically significant difference between the early and late responses. Furthermore, we used a one-component analysis to examine the total variance retrieved to check for common method bias.51 The analysis indicated that only 31.54% of the total variance was accounted for by one component, which is below the suggested threshold of 50%. Thus, it was determined that there was no prevalent issue of method bias in the collected data.

Measurement Model

The full measurement model outcomes are outlined in Table 2. Satisfactory construct consistency was achieved, as all variables exhibited Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability values surpassing the cut-off score of 0.7, demonstrating strong internal consistency, as per Hair, Risher, Sarstedt, Ringle.60 Convergent validity was likewise verified, with average variance extracted (AVE) and factor loadings surpassing 0.5 and 0.7, respectively, indicating that convergent validity was established in the study. Two criteria, the Fornell-Larcker criterion and the HTMT criterion, were used to assess discriminant validity, following the methodologies of Fornell, Larcker62 and Henseler, Ringle, Sarstedt.63 As displayed in Table 2, the research model did not exhibit any discriminant validity concerns. Discriminant validity was established since the correlations between each construct and the square root of the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) were higher than their correlations with the other constructs. The Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio was below 0.85, indicating discriminant validity among the constructs.

|

Table 2 Measurement Model Assessment |

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

To ensure the distinctiveness of the constructs in the research, a thorough confirmatory factor analysis was conducted using AMOS (v.23) software. The proposed model comprised four factors: perceived overqualification, career self-efficacy, social support and career commitment. As demonstrated in Table 3, the findings reveal that the four-factor model, as hypothesized, displayed the most favorable fit and outperformed other alternative models. Consequently, it can be concluded that the constructs are reliable and valid, making the measurement model appropriate for carrying out a structural path analysis.60

|

Table 3 Results of the Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

Structural Model

Table 4 illustrates that POQ is positively related to career self-efficacy (β= 0.351, SE= 0.065, p < 0.001) and career commitment (β= 0.265, SE= 0.058, p > 0.001). The study findings confirm hypotheses 1 and 2. We employed the bootstrapping method to determine the significance of the mediation effect as suggested by Cepeda-Carrion et al (2019). The outcomes from Table 4 demonstrate that career self-efficacy mediates the link between perceived overqualification and career commitment. This is evident from the indirect effect’s confidence interval not encompassing a value of zero (β = 0.050, 95% CI upper limit: 0.115; lower limit: 0.025) (Nitzl et al, 2016). Hence, hypothesis 3 was accepted.

|

Table 4 Hypotheses Testing |

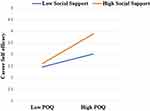

The study also revealed that social support was a significant moderator in the connection between perceived overqualification (POQ) and career self-efficacy (β =0.047, 95% CI upper limit: 0.217; lower limit: 0.041, p < 0.001), such that the positive relationship between POQ and career self-efficacy was high when social support was high (Figure 2); thus hypothesis 4a was accepted. The results presented in Figure 3 demonstrate that POQ is significantly related to career commitment, albeit indirectly via career self-efficacy. The strength of this indirect effect is dependent on social support, when social support is high, the impact of POQ on career commitment via career self-efficacy is higly pronounced (β = 0.5304, SE= 0.1835) than when psychological safety is low (β = 0.1120, SE=0.1403) as shown in Table 5. Therefore, Hypothesis 4b has been confirmed.

|

Table 5 Moderation Mediation |

|

Figure 2 Moderating role of career self-efficacy. |

|

Figure 3 SEM Results. |

Discussion

This study highlights a positive relationship between perceived overqualification and career commitment among overqualified employees, with career self-efficacy and social support playing important roles as mediators and moderators. Our results align with previous studies that have suggested a potential link between overqualification and favorable career outcomes.5,64 Specifically, Our study reveals that overqualified employees who perceive themselves as having more qualifications than what is necessary for their current job exhibit a higher level of commitment to their careers. This finding suggests that these individuals are motivated to invest in their long-term professional growth and development.29

Moreover, if employees believe they have more KSA’s than their current job requires, they may be more committed to their careers if they feel confident in their abilities and receive support from their colleagues and supervisors. Perceived overqualification can indeed lead to higher levels of self-efficacy. When individuals perceive themselves as overqualified for their job roles, it implies that they possess qualifications, knowledge, skills, and experience that exceed the requirements of their current positions. This surplus of qualifications and expertise can have a positive impact on their self-perception and self-confidence.35

By fostering a culture of support and investing in training and development programs that build career self-efficacy, organizations can enhance the commitment and productivity of their overqualified employees. Ultimately, this can lead to increased competitiveness and profitability in the marketplace. Therefore, understanding the factors that drive career commitment among overqualified employees can provide a significant competitive advantage to organizations in today’s fast-paced and ever-changing business environment.

Theoretical Implications

This study contributes to the literature in several ways. First, the positive relationship between perceived overqualification and career commitment is a relatively new area of research that adds to the literature theoretically. The traditional view posits that overqualified individuals may experience dissatisfaction,65 decreased motivation,66 and a higher likelihood of turnover.67 However, recent research has highlighted the potential positive aspects of POQ, particularly with career commitment. This new line of research goes beyond the prevailing negative assumptions about POQ. By exploring the positive aspects, it provides a more comprehensive and balanced understanding of the effects of perceived overqualification on career outcomes. The positive relationship between POQ and career commitment emphasizes the importance of career adaptability. Individuals who leverage their overqualification as an asset may demonstrate increased career resilience, adaptability, and motivation to excel in their chosen fields.68,69

Second, the role of career self-efficacy in shaping the relationship between POQ and career commitment is crucial for understanding how employees respond to their overqualification. This concept is derived from bandura’s social cognitive theory, which posits that self-efficacy influences an individual’s motivation, effort, persistence, and performance.70,71 Regarding POQ, career self-efficacy can play a significant role in determining how individuals react to their situations. Individuals with elevated levels of career self-efficacy tend to view their overqualification as a stepping stone to demonstrate commitment toward their profession. Those with high career self-efficacy strongly believe in their capabilities and are confident they can effectively apply their skills and knowledge in their current role. This confidence may enable them to seek ways to contribute more to the organization, which in turn fosters career commitment.72

Third, social support encourages a more comprehensive understanding of how individuals navigate their career paths when they perceive themselves as overqualified for their positions. The present research underscores the significance of social support in shaping career self-efficacy and commitment among individuals who possess excessive qualifications for their current job roles.73 Doing so highlights a previously under-explored factor that can help mitigate potential negative outcomes associated with perceived overqualification.29 This implies that, with adequate social support, overqualified individuals can leverage their skills and qualifications to boost their confidence in managing their careers effectively.74 This enhanced self-efficacy, in turn, can lead to increased career commitment. The present research contributes a novel perspective to the extant body of literature concerning overqualification by examining the potential advantages of perceived overqualification in conjunction with social support. This perspective challenges the predominantly negative view of overqualification in the literature and suggests that, under the right circumstances, overqualified individuals can thrive in their careers.19

Practical Implications

The findings from our research may have significant implications for hiring and administrating workers who might perceive themselves as overqualified for their positions. Employees who perceive themselves as overqualified but highly committed to their careers may be likelier to stay with the organization. Employers can focus on recognizing and leveraging these employees’ skills and commitment to improve retention rates. By understanding the motivations behind employees’ career commitment, managers can create targeted opportunities for growth and advancement within the organization, increasing employee engagement and satisfaction. Employers can use this information to develop customized training and development programs that enhance employees’ skills and capabilities, helping them grow in their careers and feel more satisfied with their roles.

Organizations can design jobs and roles that better use overqualified employees’ skills and talents. This may involve creating more challenging projects, offering job rotations, or providing opportunities for employees to contribute to other areas of the organization. Understanding the relationship between perceived overqualification and career commitment can help employers establish performance management systems that account for employees’ perceived skill levels and career goals, fostering a more motivated and productive workforce. Organizations can revise their recruitment and selection processes to ensure that they are hiring candidates who are both qualified and committed to their careers, leading to a better overall fit between employees and the organization. Employers can encourage employees to take ownership of their professional development and growth by fostering a culture that values career commitment, promoting a more motivated and engaged workforce.

Limitations and Future Avenues

While the relationship between POQ and career commitment has been studied, some limitations warrant consideration and future research avenues to explore this topic further. The existing studies may have been conducted in specific industries or cultures, which could limit the generalizability of the findings. Future research could investigate this relationship across different industries, countries, and cultural contexts to better understand the extent to which the findings apply universally. Additional factors could influence the relationship between perceived overqualification and career commitment, such as personality traits, job characteristics, or organizational culture. Future research should explore potential moderators to provide a more nuanced understanding of this relationship. It would be valuable for future research to investigate how perceived overqualification influences career commitment. This could include examining job satisfaction, psychological well-being, or work-life balance. Future research could focus on designing and evaluating interventions to reduce perceived overqualification or enhance career commitment, on providing practical guidance for organizations in managing overqualified employees. Most studies may have relied on quantitative methodologies. Future research could incorporate qualitative approaches, such as interviews or focus groups, to gain deeper insights into employees’ experiences and perspectives on POQ and career commitment.

Conclusion

POQ have a positive relationship with career commitment, and this association can be explained by the mediating role of career self-efficacy. When employees perceive themselves as overqualified for their job, they are more likely to feel that they are utilizing their full potential and capabilities. This sense of fulfillment and accomplishment can contribute to an increased belief in their own abilities to succeed in their career, which is known as career self-efficacy. Employees who have higher levels of career self-efficacy are more likely to be committed to their career paths. This is because they feel confident in their ability to take on challenging tasks, perform job responsibilities effectively, and achieve their career goals. They are motivated to invest in their current job to gain the necessary skills and experiences that align with their long-term career aspirations.

Furthermore, the relationship between POQ, career self-efficacy, and career commitment can be influenced by social support. When employees receive support from colleagues, supervisors, and the organization as a whole, it enhances their sense of value, belonging, and encouragement. This supportive work environment can contribute to employees’ career self-efficacy, as they feel recognized and affirmed in their abilities and potential. Consequently, this can further strengthen their commitment to their career. Organizations should recognize and embrace the potential benefits of perceived overqualification by creating a work environment that fosters employee development, growth, and social support. Providing opportunities for employees to utilize their skills fully, offering challenging assignments, and recognizing their contributions can enhance their sense of fulfillment and career self-efficacy. Additionally, promoting a supportive culture where colleagues and supervisors provide assistance, encouragement, and mentoring can contribute to employees’ overall well-being and commitment to their careers. By acknowledging the positive aspects of perceived overqualification and actively cultivating a supportive work environment, organizations can improve employee performance, job satisfaction, and retention. Moreover, this approach can lead to a more engaged and committed workforce, which ultimately benefits the organization’s productivity and success. Organizations should leverage these findings to create an environment that encourages employee development, growth, and social support, ultimately promoting employee satisfaction, performance, and long-term commitment to their careers.

Ethical Statement

The study followed the ethical principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration 1964 and its subsequent amendments. It was also approved by the ethics committees of Zhaotong University, Zhaotong 657000, China. In addition, all participants provided informed consent before participating in the study.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Rozelle S, Xia Y, Friesen D, Vanderjack B, Cohen N. Moving Beyond Lewis: employment and Wage Trends in China’s High-and Low-Skilled Industries and the Emergence of an Era of Polarization: presidential Address for the 2020 Association for Comparative Economic Studies Meetings. Comp Econ Stud. 2020;62:555–589. doi:10.1057/s41294-020-00137-w

2. Yeşiltaş M, Arici HE, Sormaz Ü. Does perceived overqualification lead employees to further knowledge hiding? The role of relative deprivation and ego depletion. Int J Contemporary Hospit Manag. 2022;35:1880.

3. Erdogan B, Bauer TN. Overqualification at work: a review and synthesis of the literature. Ann Rev Org Psychol Org Behav. 2021;8:259–283. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012420-055831

4. Erdogan B, Karakitapoğlu‐Aygün Z, Caughlin DE, Bauer TN, Gumusluoglu L. Employee overqualification and manager job insecurity: implications for employee career outcomes. Hum Resour Manage. 2020;59(6):555–567. doi:10.1002/hrm.22012

5. Ma C, Ganegoda DB, Chen ZX, Jiang X, Dong C. Effects of perceived overqualification on career distress and career planning: mediating role of career identity and moderating role of leader humility. Hum Resour Manage. 2020;59(6):521–536. doi:10.1002/hrm.22009

6. Zhang M, Wang F, Weng H, Zhu T, Liu H. Transformational leadership and perceived overqualification: a career development perspective. Front Psychol. 2021;12:597821. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.597821

7. Khan J, Saeed I, Zada M, Nisar HG, Ali A, Zada S. The positive side of overqualification: examining perceived overqualification linkage with knowledge sharing and career planning. J Knowledge Management. 2023;27(4):993–1015. doi:10.1108/JKM-02-2022-0111

8. Khassawneh O, Mohammad T, Ben-Abdallah R. The Impact of Leadership on Boosting Employee Creativity: the Role of Knowledge Sharing as a Mediator. Adm Sci. 2022;12(4):175. doi:10.3390/admsci12040175

9. Goulet LR, Singh P. Career commitment: a reexamination and an extension. J Vocat Behav. 2002;61(1):73–91. doi:10.1006/jvbe.2001.1844

10. Maynard DC, Brondolo EM, Connelly CE, Sauer CE. I’m too good for this job: narcissism’s role in the experience of overqualification. Appl Psychol. 2015;64(1):208–232. doi:10.1111/apps.12031

11. Aslam S, Shahid MN, Sattar A. Perceived Overqualification as a Determinant of Proactive Behavior and Career Success: the Need for Achievement as a Moderator. J Entre Manage Innovation. 2022;4(1):167–187. doi:10.52633/jemi.v4i1.152

12. Dar N, Rahman W. Two angles of overqualification-The deviant behavior and creative performance: the role of career and survival job. PLoS One. 2020;15(1):e0226677. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0226677

13. Betz NE. Career self-efficacy: exemplary recent research and emerging directions. J Career Assessment. 2007;15(4):403–422. doi:10.1177/1069072707305759

14. Ahmed NOA. Career commitment: the role of self-efficacy, career satisfaction and organizational commitment. World J Entrepreneurship Manage Sustainable Dev. 2019;28:45.

15. Chang HY, Lee IC, Chu TL, Liu YC, Liao YN, Teng CI. The role of professional commitment in improving nurses’ professional capabilities and reducing their intention to leave: two‐wave surveys. J Adv Nurs. 2019;75(9):1889–1901. doi:10.1111/jan.13969

16. Cunningham MR, Barbee AP. Social support. Close Relationships. 2000:273.

17. Taylor SE. Social support: a review. Oxford Handbook Health Psychol. 2011;1:189.

18. Uddin MK, Azim MT, Islam MR. Effect of perceived overqualification on work performance: influence of moderator and mediator. Asia Pacific Manage Rev. 2022. doi:10.1016/j.apmrv.2022.10.005

19. Zhang Y, Bolino MC, Yin K. The interactive effect of perceived overqualification and peer overqualification on peer ostracism and work meaningfulness. J Business Ethics. 2022;1–18.

20. Khassawneh O, Elrehail H. The Effect of Participative Leadership Style on Employees’ Performance: the Contingent Role of Institutional Theory. Adm Sci. 2022;12(4):195. doi:10.3390/admsci12040195

21. Kim J, Park J, Sohn YW, Lim JI. Perceived overqualification, boredom, and extra-role behaviors: testing a moderated mediation model. J Career Dev. 2021;48(4):400–414. doi:10.1177/0894845319853879

22. Kaymakcı R, Görener A, Toker K. The perceived overqualification’s effect on innovative work behaviour: do transformational leadership and turnover intention matter? Curr Res Behav Sci. 2022;3:100068. doi:10.1016/j.crbeha.2022.100068

23. Su Y, Li M, Chen G. Perceived over-qualification of primary school teachers and its impact on career satisfaction—A empirical study based on the survey data. Int J Electrical Eng Educ. 2021;00207209211003266.

24. Woo HR. Perceived overqualification and job crafting: the curvilinear moderation of career adaptability. Sustainability. 2020;12(24):10458. doi:10.3390/su122410458

25. Lee A, Erdogan B, Tian A, Willis S, Cao J. Perceived overqualification and task performance: reconciling two opposing pathways. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2021;94(1):80–106. doi:10.1111/joop.12323

26. Gkorezis P, Erdogan B, Xanthopoulou D, Bellou V. Implications of perceived overqualification for employee’s close social ties: the moderating role of external organizational prestige. J Vocat Behav. 2019;115:103335. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2019.103335

27. Wang P, Yang S, Sun N, et al. College students’ perceived overqualification and adaptation: a double-edged sword model. Curr Psychol. 2022;1–19.

28. Bani-Melhem S, Abukhait RM, Mohd Shamsudin F. This doesn’t make sense! Does illegitimate tasks affect innovative behaviour? Service Industries J. 2023;1–27. doi:10.1080/02642069.2022.2163994

29. Lobene EV, Meade AW. The effects of career calling and perceived overqualification on work outcomes for primary and secondary school teachers. J Career Dev. 2013;40(6):508–530. doi:10.1177/0894845313495512

30. Bani-Melhem S, Shamsudin FM, Abukhait R, Al-Hawari MA. Competitive psychological climate as a double-edged sword: a moderated mediation model of organization-based self-esteem, jealousy, and organizational citizenship behaviors. J Hospitality Tourism Manage. 2023;54:139–151. doi:10.1016/j.jhtm.2022.12.011

31. Chung YB. Career decision-making self-efficacy and career commitment: gender and ethnic differences among college students. J Career Dev. 2002;28(4):277–284. doi:10.1177/089484530202800404

32. Lu L, Luo T, Zhang Y. Perceived overqualification and deviant innovation behavior: the roles of creative self-efficacy and perceived organizational support. Front Psychol. 2023;14.

33. Rasheed MI, Weng Q, Umrani WA, Moin MF. Abusive supervision and career adaptability: the role of self-efficacy and coworker support. Human Performance. 2021;34(4):239–256. doi:10.1080/08959285.2021.1928134

34. Afshari L. Managing diverse workforce: how to safeguard skilled migrants’ self-efficacy and commitment. Int J Cross Cultural Manag. 2022;22(2):235–250. doi:10.1177/14705958221096526

35. Chu F, Liu S, Guo M, Zhang Q. I am the top talent: perceived overqualification, role breadth self-efficacy, and safety participation of high-speed railway operators in China. Saf Sci. 2021;144:105476. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2021.105476

36. Meng Q. Chinese university teachers’ job and life satisfaction: examining the roles of basic psychological needs satisfaction and self-efficacy. J Gen Psychol. 2022;149(3):327–348. doi:10.1080/00221309.2020.1853503

37. Rowles P, Cox C, Pool GJ. Who is called to work? The importance of calling when considering universal basic income. Ind Organ Psychol. 2021;14(4):582–585. doi:10.1017/iop.2021.119

38. Sahito Z, Vaisanen P. A literature review on teachers’ job satisfaction in developing countries: recommendations and solutions for the enhancement of the job. Rev Educ. 2020;8(1):3–34. doi:10.1002/rev3.3159

39. Jia Y, Hou Z-J, Wang D. Calling and career commitment among Chinese college students: career locus of control as a moderator. Int J Educ Vocational Guidance. 2021;21:211–230. doi:10.1007/s10775-020-09439-y

40. Peng X, Yu K, Zhang K, Xue H, Peng J. Perceived Overqualification and Intensive Smartphone Use: a Moderated Mediation Model. Front Psychol. 2022;13:278.

41. Sesen H, Ertan SS. Perceived overqualification and job crafting: the moderating role of positive psychological capital. Personnel Rev. 2020;49(3):808–824. doi:10.1108/PR-10-2018-0423

42. Sun Y, Qiu Z. Perceived Overqualification and Innovative Behavior: high-Order Moderating Effects of Length of Service. Sustainability. 2022;14(6):3493. doi:10.3390/su14063493

43. Wang H-J, Chen X, C-q L. When career dissatisfaction leads to employee job crafting: the role of job social support and occupational self-efficacy. Career Dev Int. 2020;25(4):337–354. doi:10.1108/CDI-03-2019-0069

44. Lee PC, Xu ST, Yang W. Is career adaptability a double-edged sword? The impact of work social support and career adaptability on turnover intentions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Hospitality Manage. 2021;94:102875. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.102875

45. Van der Laken P, Van Engen M, Van Veldhoven M, Paauwe J. Fostering expatriate success: a meta-analysis of the differential benefits of social support. Human Resource Manage Rev. 2019;29(4):100679. doi:10.1016/j.hrmr.2018.12.003

46. Caines V, Earl JK, Bordia P. Self-employment in later life: how future time perspective and social support influence self-employment interest. Front Psychol. 2019;10:448. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00448

47. Jolly PM, Kong DT, Kim KY. Social support at work: an integrative review. J Organ Behav. 2021;42(2):229–251. doi:10.1002/job.2485

48. Skowronski M. Overqualified Employees: a Review, A Research Agenda, and Recommendations for Practice. J Appl Business Economics. 2019;21(1):8768.

49. Zhang J, Akhtar MN, Zhang Y, Sun S. Are overqualified employees bad apples? A dual-pathway model of cyberloafing. Internet Res. 2020;30(1):289–313. doi:10.1108/INTR-10-2018-0469

50. Li Y, Li Y, Yang P, Zhang M. Perceived Overqualification at Work: implications for Voice Toward Peers and Creative Performance. Front Psychol. 2022;13.

51. Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

52. Maynard DC, Joseph TA, Maynard AM. Underemployment, job attitudes, and turnover intentions. J Org Behav. 2006;27(4):509–536. doi:10.1002/job.389

53. van der Heijden B No one has ever promised you a rose garden.

54. Jaskolka G, Beyer JM, Trice HM. Measuring and predicting managerial success. J Vocat Behav. 1985;26(2):189–205. doi:10.1016/0001-8791(85)90018-1

55. Betz NE, Klein KL, Taylor KM. Evaluation of a short form of the career decision-making self-efficacy scale. J Career Assessment. 1996;4(1):47–57. doi:10.1177/106907279600400103

56. Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52(1):30–41. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2

57. Bogilović S, Černe M, Škerlavaj M. Hiding behind a mask? Cultural intelligence, knowledge hiding, and individual and team creativity. Eur J Work Org Psychol. 2017;26(5):710–723. doi:10.1080/1359432X.2017.1337747

58. Zhao H, Liu W, Li J, Yu X. Leader–member exchange, organizational identification, and knowledge hiding: t he moderating role of relative leader–member exchange. J Organ Behav. 2019;40(7):834–848. doi:10.1002/job.2359

59. Sanchez-Franco MJ, Cepeda-Carrion G, Roldan JL. Understanding relationship quality in hospitality services: a study based on text analytics and partial least squares. Internet Res. 2019;29(3):478–503. doi:10.1108/IntR-12-2017-0531

60. Hair JF, Risher JJ, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur Business Rev. 2019;31(1):2–24. doi:10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

61. Armstrong JS, Overton TS. Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. J Marketing Res. 1977;14(3):396–402. doi:10.1177/002224377701400320

62. Fornell C, Larcker DF. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications Sage CA; 1981.

63. Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J Academy Marketing Sci. 2015;43:115–135. doi:10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

64. Khassawneh O, Mohammad T, Momany MT. Perceived Overqualification and Job Outcomes: the Moderating Role of Manager Envy. Sustainability. 2023;15(1):84. doi:10.3390/su15010084

65. Arvan ML, Pindek S, Andel SA, Spector PE. Too good for your job? Disentangling the relationships between objective overqualification, perceived overqualification, and job dissatisfaction. J Vocat Behav. 2019;115:103323. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2019.103323

66. Chambel MJ, Carvalho VS, Lopes S, Cesário F. Perceived overqualification and contact center workers’ burnout: are motivations mediators? Int J Org Analysis. 2021;29(5):1337–1349. doi:10.1108/IJOA-08-2020-2372

67. Li W, Xu A, Lu M, Lin G, Wo T, Xi X. Influence of primary health care physicians’ perceived overqualification on turnover intention in China. Quality Manage Healthcare. 2020;29(3):158–163. doi:10.1097/QMH.0000000000000259

68. Russell ZA, Ferris GR, Thompson KW, Sikora DM. Overqualified human resources, career development experiences, and work outcomes: leveraging an underutilized resource with political skill. Human Resource Manage Rev. 2016;26(2):125–135. doi:10.1016/j.hrmr.2015.09.008

69. Yang W, Guan Y, Lai X, She Z, Lockwood AJ. Career adaptability and perceived overqualification: testing a dual-path model among Chinese human resource management professionals. J Vocat Behav. 2015;90:154–162.

70. Pekkala K, van Zoonen W. Work-related social media use: the mediating role of social media communication self-efficacy. Eur Manage J. 2022;40(1):67–76. doi:10.1016/j.emj.2021.03.004

71. Bani-Melhem S, Abukhait R, Shamsudin FM, Al-Hawari MA. How and when does job challenge promote the innovative behaviour of public sector employees? Int J Innovation Manage. 2021;25(06):2150069. doi:10.1142/S1363919621500699

72. Stewart J, Henderson R, Michaluk L, Deshler J, Fuller E, Rambo-Hernandez K. Using the social cognitive theory framework to chart gender differences in the developmental trajectory of STEM self-efficacy in science and engineering students. J Sci Educ Technol. 2020;29:758–773. doi:10.1007/s10956-020-09853-5

73. Mohammad T, Darwish TK, Singh S, Khassawneh O. Human resource management and organisational performance: the mediating role of social exchange. Eur Manag Rev. 2021;18(1):125–136. doi:10.1111/emre.12421

74. Deng H, Guan Y, Wu C-H, Erdogan B, Bauer T, Yao X. A relational model of perceived overqualification: the moderating role of interpersonal influence on social acceptance. J Manage. 2018;44(8):3288–3310. doi:10.1177/0149206316668237

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.