Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 17

The Relationship Between Childhood Trauma and Non-Suicidal Self-Injury Behavior in Adolescents with Depression: The Mediating Role of Rumination

Authors Fu W , Li X, Ji S, Yang T, Chen L, Guo Y, He K

Received 18 November 2023

Accepted for publication 21 March 2024

Published 6 April 2024 Volume 2024:17 Pages 1477—1485

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S448248

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Mei-Chun Cheung

Wenxian Fu,1– 4 Xinyi Li,1– 4 Sifan Ji,1– 4 Tingting Yang,1,3– 5 Lu Chen,1,3– 5 Yaru Guo,1,3– 5 Kongliang He1– 5

1Affiliated Psychological Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Hefei Fourth People’s Hospital, Hefei, 230022, People’s Republic of China; 2School of Mental Health and Psychological Sciences, Anhui Medical University, Hefei, 230022, People’s Republic of China; 3Anhui Mental Health Center, Hefei Fourth People’s Hospital, Hefei, 230022, People’s Republic of China; 4Psychiatry Department, Hefei Fourth People’s Hospital, Hefei, 230022, People’s Republic of China; 5Psychological Counseling department, Hefei Fourth People’s Hospital, Hefei, 230022, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Kongliang He, Affiliated Psychological Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Hefei Fourth People’s Hospital, Hefei, 230022, People’s Republic of China, Tel +8613966721862, Email [email protected]

Objective: Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) behavior is very common in adolescents with depression, and childhood trauma is considered one of the distal risk factors for its exacerbation. Rumination caused by adverse traumatic experiences, which can be transferred through NSSI behavior, can alleviate symptoms of depression in adolescents. The current research focuses on the relationship between the three, further exploring whether rumination is a mediator in the relationship between childhood trauma and NSSI behavior on the basis of previous studies, and provides some suggestions for future early intervention for adolescents with depression.

Methods: A total of 833 adolescent patients with depression who met the DSM-5 criteria for depressive episode were recruited from 12 hospitals in China. The Chinese version of the Function Assessment of Self-mutilation, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire, and Rumination Inventory were used as research tools.

Results: The scores of childhood trauma and rumination in adolescents with depression in the NSSI group were higher than those in the non-NSSI group. A Pearson’s correlation analysis showed that childhood trauma was positively correlated with rumination (r=0.165, P< 0.01), different types of childhood trauma were significantly positively correlated with rumination and its three factors, and these results were statistically significant. Rumination partially mediated the relationship between childhood trauma and NSSI behavior in depressed adolescent patients (effect size=0.002), and the effect in female participants (effect size=0.003), was greater than that in male participants (effect size=0.002).

Conclusion: Childhood trauma and rumination were key factors for NSSI behavior in adolescents with depression. Childhood trauma not only has a direct effect on NSSI behavior in adolescent depression, but also plays an indirect effect on NSSI behavior through rumination.

Keywords: adolescents, childhood trauma, rumination, non-suicidal self-injury

Introduction

Depression is a common psychiatric disorder in clinical practice, often accompanied by cognitive impairment and high suicide risk.1 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), depression ranks third in the global burden of disease, and the prevalence is increasing year by year, especially among adolescents.2 Adolescents with depression are more likely to engage in self-criticism and negative emotions than healthy adolescents, and persistent depressive symptoms increase the risk of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) behaviors.3 NSSI is a form of self-harm that intentionally or directly harms body tissues without suicidal intent, including cutting, scraping, biting, and impacting.4 This behavior is common, usually occurs in early adolescence,5 and is not easily of concern. According to the survey, the behavioral prevalence of NSSI in Chinese adolescents with depression and bipolar disorder is 62.2%.6 NSSI behavior not only has a certain adverse effect on individual mental health but repeated NSSI behavior can also predict suicidal and impulsive behavior,7 which has become a key issue of increasing social concern. Based on the above situation, early identification of risk factors is particularly important for the exploration and intervention of etiology. Therefore, this study is aimed at the two major risk factors influencing this behavior, namely childhood trauma and ruminative thinking.

Childhood trauma can be defined as an adverse experience in early life, is a psychosocial factor capable of negatively affecting health,8 is closely related to depression, anxiety, etc., and plays an important role in the course and prognosis of the disease.9 It can lead to a negative experience of emotional or social dysregulation in the adolescent when faced with challenging or stressful life events. Brown et al showed that people with a history of childhood trauma were significantly more likely to develop NSSI,10 up to 2.7 to 6.1 times.11 Neurobiological mechanisms suggest that patients with traumatic childhood experiences may have dysfunction of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, resulting in impaired mood regulation. NSSI behavior is a behavior that can reduce the interpersonal communication and learning disabilities caused by childhood trauma by regulating the experiential needs of adolescents,12 so as to achieve the purpose of regulating the functional relationship between childhood trauma and the HPA axis.13 Taken together, it has been suggested that there may be a strong association between childhood trauma and self-harm, even stronger than the impact of other risk factors on self-harm.14

Rumination refers to the fact that after an individual has suffered a negative life event, he repeatedly think about the causes and various adverse consequences of the event, and when the individual has difficulty getting rid of the negative emotion, a physical and mental illness (mental disorder) might occur.15 There is significant evidence of a strong association between the severity of childhood trauma and ruminative thinking.16,17 Early research by Seth et al showed that adolescents who had experienced childhood trauma were more likely to develop ruminative thinking and focus on negative emotions that led to the risk of depression than adolescents who had not experienced childhood trauma.18 This is consistent with the findings presented by Disner et al in 2011,19 which show that individuals who have experienced negative childhood events are more likely to form negative self-thoughts, which are further exacerbated by ruminative thoughts. The emotional cascade model proposed by Selby et al postulates that the process starts with a small emotional stimulus, and through one rumination cycle after another, the stimulus is amplified, causing the individual to experience some pain that cannot be relieved. Rumination, on the other hand, is a process of attentional deployment, which is further exacerbated when an individual’s attention is focused on a painful experience, leading to a vicious circle of attention to the emotional level of the ruminant mind.20 NSSI behavior can shift the patient’s attention away from ruminating thoughts to intense somatosensory sensations, thus terminating the emotional cascade. Therefore, whether there is a certain relationship between childhood trauma as a negative experience that can easily cause rumination and NSSI behavior is the direction that we need to study further.

The purpose of this study was to (1) investigate the relationship between childhood trauma, rumination, and non-suicidal self-injury behavior in adolescents with depression and (2) verify whether rumination plays a mediating role in the relationship between childhood trauma and non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents with depression.

Materials and Methods

Participants

In this study, a cross-sectional survey was conducted to collect samples of adolescents with depression in the outpatient and inpatient departments of 12 hospitals in China from January to December 2021. The participants were surveyed by questionnaire, and a total of 883 valid questionnaires were collected, of which 651 were completed by females and 232 by males. Informed consent forms signed by all participants and guardians.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Criteria for inclusion:

- met the diagnostic criteria for a depressive episode as defined by the DSM-5 or a depressive episode of bipolar disorder (ie, outpatient depression status met the criteria for a depressive episode);

- 12–18 years of age;

- years of education≥ 6 years;

- no previous history of suicidal behavior;

- adolescent participants are eligible for consent after the consent of the guardians, and all participants and guardians fully understand the content and purpose of the study, and provide written informed consent.

Exclusion criteria:

- patients with severe physical, infectious or immune system diseases;

- patients with known serious organic brain or neurological diseases;

- patients with a history of schizophrenia, mental retardation, or other serious mental disorder.

Measures

General Information

General demographic information about the participants was collected using a questionnaire developed by the study team itself, including age, gender, and ethnicity.

Functional Assessment of Self-Mutilation

The FASM, designed by Lloyd et al, has been widely used in the assessment of NSSI in adolescents.21 This study mainly used C-FASM quantities.22 This paper mainly analyzed the list of NSSI behaviors (such as cutting, burning, intentionally beating oneself, etc.), and found out whether the subjects intentionally carried out any of the ten different NSSI behaviors listed in the evaluation form in the past 12 months, including frequency, severity, treatment mode, duration, etc. Cronbach’s α of the sample in this study was 0.991.

RRS Rumination Scale

The Rumination Inventory consists of 22 items to measure the rumination response to negative emotions.15 Three factors were included: symptom rumination, brooding, and reflective pondering. Using a 4-point Likert scale, each item was rated from 1 to 4, with 1=never, 2=sometimes, 3=often, and 4=always, with higher scores indicating greater rumination tendencies. The Cronbach’s α of this study was 0.938.

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire

The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ),23 developed by Bernstein and Fink, is a 28-item self-report checklist designed to measure five subtypes of childhood or adolescent abuse or neglect: physical abuse, physical neglect, emotional neglect, emotional abuse, and sexual abuse. A 5-point scale was used for each item, never =1, occasionally =2, sometimes =3, often =4, and always =5, with scores ranging from 5 to 25 for each type of childhood trauma and a total score ranging from 28 to 140. Questions 10, 16, and 22 were used for assessment and were not scored. Childhood trauma was defined as physical abuse ≥10 points, physical neglect ≥10 points, emotional abuse ≥13 points, emotional neglect ≥15 points, and sexual abuse ≥8 points. With the exception of somatic neglect, the internal consistency of each subscale was relatively good. The coefficients of CTQ were 0.829 (physical abuse), 0.829 (emotional neglect), 0.740 (emotional abuse), 0.863 (sexual abuse), and 0.504 (physical neglect).

Statistical Analyses

SPSS 25.0 software was used for statistical analysis. Normally distributed measurements are expressed as mean ± standard deviations. An independent sample t-test was used to compare the differences in self-harm in the general demographic data of adolescent patients with depression. Correlation between childhood trauma, rumination thinking and NSSI behavior in adolescents with depression were calculated using Pearson’s correlation analysis. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to assess the hypothesized relationship between childhood trauma, rumination, and NSSI behavior, and the basic and mediation models were evaluated. The basic model validated the relationship between childhood trauma and NSSI behavior, and the mediation model evaluated the direct and indirect relationship between childhood trauma and NSSI behavior through rumination as a mediator. R4.3.1 was used to analyze the mediating effect, with childhood trauma as the independent variable and NSSI behavior as the dependent variable. The Lavaan package was used to verify the significance of the mediating effect of rumination in the relationship between childhood trauma and NSSI. A fit degree analysis was conducted at an early stage, which was the most suitable model. The data generated have a 95% confidence interval, and p<0.05 is considered a significant difference.

Results

Analysis of Differences Between the Two Groups

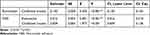

The independent sample t-test between the two groups is shown in Table 1. The results showed that adolescents with depression in the NSSI group had significantly higher scores for childhood trauma and each sub-type than those in the non-NSSI group. The total score of rumination and its three factors differed in the scores of the two groups, with the NSSI group scoring significantly higher.

|

Table 1 Differences Between CTQ and RRS Scores in Adolescents with Depression Without NSSI-Related Behaviors |

Correlation Analysis

Pearson’s correlation analysis was selected to analyze childhood trauma, rumination thinking and NSSI behavior in adolescent depression. The results in Table 2 show that childhood trauma was significantly positively correlated with rumination (r=0.165, P < 0.01) and its three factors (symptomatic rumination, compulsive thinking, and introspection and rumination). The different types of childhood trauma were also positively correlated with rumination and its three factors.

|

Table 2 Correlation Analysis Between Childhood Trauma and Its Subtypes and Rumination Thinking |

Mediating Role of Rumination in the Relationship Between Childhood Trauma and NSSI Behavior

Based on correlation analysis, an intermediary model was constructed (Table 3). The results showed that the- regression coefficient was standardized, and the analysis result is shown in Figure 1. The total effect size of childhood trauma on NSSI was 0.012 (Figure 1a), the direct effect was 0.009, and the indirect effect was 0.002 (Figure 1b). Childhood trauma not only directly affected NSSI behavior, but may also affect NSSI behavior by influencing an individual’s rumination and thus NSSI behavior.

|

Table 3 Mediating Effect of Rumination on the Association Between Childhood Trauma and NSSI |

Based on this, the study further analyzed gender as a factor. The analysis of female patients only is shown in Figure 2, and the analysis of male patients only is shown in Figure 3. In female subjects, the total effect of childhood trauma on NSSI was 0.020 (Figure 2a), the direct effect was 0.016, and the mediating effect value through rumination was 0.003 (Figure 2b). In male subjects, the effect size of childhood trauma on NSSI was 0.009 for the total effect (Figure 3a), 0.007 for the direct effect, and 0.002 for the mediating effect through rumination (Figure 3b).

Discussion

The results of this study suggest that childhood trauma is significantly associated with NSSI behavior in adolescent depression, and rumination is associated with NSSI behavior and childhood trauma. Further analysis showed that rumination was the mediating factor between childhood trauma and NSSI. Therefore, childhood trauma directly or indirectly increases NSSI behavior in adolescents with depression through rumination. These findings may play an important role in the early identification of risk factors and intervention in NSSI behavior in adolescents with depression.

Ruminative thinking, childhood traumatic experiences, and NSSI behavior were significantly correlated among adolescents with depression, and the five types of childhood trauma (emotional neglect, physical neglect, emotional abuse, physical abuse, and sexual abuse) were significantly correlated with ruminative thinking and non-suicidal self-injury behavior. This is consistent with previous findings.16,24 Our study identified that childhood trauma is associated with rumination. On the basis of previous studies, our study further found that each type of childhood traumatic experience is significantly positively correlated with ruminative thinking, and the more childhood traumatic experiences one has had, the stronger the ruminative thinking, and childhood trauma can predict ruminative thinking. A study on Chinese adolescents found a significant positive correlation between childhood trauma and NSSI.25 Our study further classified different types of childhood traumatic experiences and found a significant positive correlation between them and NSSI. The likelihood and frequency of non-suicidal self-injury behavior were higher in adolescents with depression. Unlike other previous studies, Glassman et al’s study showed that emotional and sexual abuse were significantly associated with NSSI behavior, while physical abuse was not significantly associated with NSSI behavior,26 which is inconsistent with the results of this study.

Our results showed that childhood trauma scored higher in patients with NSSI behavior, indicating a positive relationship between childhood trauma and NSSI behavior. This is consistent with the findings of Chen et al, who showed a significant increase in NSSI behavior in individuals with high levels of childhood trauma.27 This may be because when individuals encounter adverse experiences in childhood, they are not mature in cognition, thinking style, and personality characteristics, lack inner stability, and they are in a critical period of development, so individuals cannot acquire the ability to adapt and solve problems. This has also been confirmed by research that childhood adversity disrupts the ability to regulate or manage negative emotional states, leading to an increased risk of personal emotional problems and extreme distress. Therefore, when facing stressors in the growth process, NSSI can only be adopted to cope with them.28

The results of the mediating effect analysis in our study showed that rumination partially mediated the relationship between childhood trauma and NSSI behavior in adolescent depressed patients. Childhood trauma could not only directly affect NSSI behavior in adolescents with depression, but also indirectly affect NSSI behavior through rumination. Compared with patients without NSSI behaviors, adolescents with depression in the NSSI behavior group had higher rumination scores, and childhood trauma was positively correlated with rumination, which was consistent with the findings of Rodenas-Perea et al.29 One possible mechanism is that individuals who have experienced childhood trauma lack control over their emotions and are more likely to have negative emotions, which further leads to higher emotional responses.30 When faced with certain adverse events, such individuals often adopt inappropriate ways to regulate their emotions, such as NSSI behavior, suicide, etc. Ruminative thinking is a strategy for coping with traumatic experiences31 and is closely related to negative psychological outcomes.32 It can be argued that after experiencing childhood trauma, it is easy to constantly recall and focus on one’s own painful emotions and experiences as a maladaptive strategy to cope with negative emotions and pain. The study by Ghazanfari et al also demonstrated that childhood abuse may be related to psychological states, such as anxiety, anger, and aggressive behavior.33 Although rumination may be used as a form of self-regulation, it can ultimately backfire and lead to the occurrence of NSSI behavior.

Our study also found that the effect of childhood trauma on NSSI behavior and the role of rumination in the relationship between childhood trauma and NSSI behavior were greater in women than in men. This is consistent with most reports in the prior literature, stating that women are more prone to rumination than men.34,35 The results showed that compared with men, childhood trauma experiences in women may lead to more ruminative cognitive responses, which, in turn, lead to more painful experiences and the protracted development of emotional problems, ultimately leading to the occurrence of maladaptive behaviors. Studies have shown that women are more likely than men to experience negative emotions and difficulties in controlling social events and emotional experiences, and they often hold themselves responsible for poor outcomes.36 Women are more likely to internalize their emotional pain,37 “Women are twice as likely as men to suffer from emotional instability”.38 This explains why depression and stress-related psychiatric disorders are more common in women. The interaction of rumination with adverse childhood experiences to trigger emotional and behavioral dysregulation may be stronger in women than in men. For the impact in both sex groups, the dominance of women in the role of rumination is justified.

Limitations and Prospects

This study involved 883 participants from 12 hospitals in different regions. The study was representative in terms of exploring NSSI behavior and its relationship with childhood trauma and rumination in adolescent patients with depression from multiple dimensions. However, there are some limitations. First, our study was cross-sectional, focused only on the past 12 months, and did not have a long follow-up. Second, the use of self-assessment questionnaires to collect data may cause recall errors, resulting in insufficient strength of the association between the final results. In the next step, other ways can be used for comprehensive and more objective measurement. Finally, our participants included more women than men, a difference that reflects differences in the prevalence of puberty between the sexes and may affect the generalizations of our findings to men. Therefore, further follow-up of participants, longitudinal design to explore the association between childhood trauma, rumination, and NSSI behaviors, and generalization to a more representative sample, attention to the composition of the male-to-female ratio, and consideration of more factors influencing NSSI behaviors may be needed in the future to provide targets for prevention and intervention.

Conclusion

The results of this study suggest that childhood traumatic experiences and rumination increase the risk of NSSI behavior in adolescents with depression, highlighting the interaction of childhood trauma and rumination that influences NSSI behavior. In addition, future research should explore clinically relevant issues by measuring adverse childhood experiences, rumination, and NSSI with more objective and comprehensive methods, which would help to identify the occurrence of self-harm behaviors in adolescents with depression who are most in need of early intervention.

Ethical Approval and Consent to Participate

All information of this study were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Fourth People’s Hospital of Hefei. It was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants and their guardians signed a written informed consent form at the beginning of the study.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Hefei Fourth People’s Hospital for their support.

Funding

This study was supported by Key Projects of Applied Medical Research of Hefei Health Care Commission (Hwk2021zd013), Fund project of Anhui Medical University (2022xkj118, 2022xkj116), Anhui Provincial Clinical Medical Research Transformation Project (No. 202204295107020005) and Key Laboratory of Philosophy and Social Science of Anhui Province on Adolescent Mental Health and Crisis Intelligence Intervention (SYS2023B10).

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare in this work.

References

1. Kwong ASF, Manley D, Timpson NJ, et al. Identifying critical points of trajectories of depressive symptoms from childhood to young adulthood. J Youth Adolesc. 2019;48(4):815–827. doi:10.1007/s10964-018-0976-5

2. Liu Q, He H, Yang J, Feng X, Zhao F, Lyu J. Changes in the global burden of depression from 1990 to 2017: findings from the Global Burden of Disease study. J Psychiatr Res. 2020;126:134–140. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.08.002

3. Zubrick SR, Hafekost J, Johnson SE, Sawyer MG, Patton G, Lawrence D. The continuity and duration of depression and its relationship to non-suicidal self-harm and suicidal ideation and behavior in adolescents 12–17. J Affect Disord. 2017;220:49–56. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2017.05.050

4. Plener PL, Kaess M, Fau - Schmahl C, et al. Nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescents; 2018.

5. Cipriano A, Cella S, Cotrufo P. Nonsuicidal self-injury: a systematic review. Front Psychol. 2017;8:1946. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01946

6. Wang L, Liu J, Yang Y, Zou H. Prevalence and risk factors for non-suicidal self-injury among patients with depression or bipolar disorder in China. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):389. doi:10.1186/s12888-021-03392-y

7. Brown RC, Plener PL. Non-suicidal self-injury in adolescence. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19(3):20. doi:10.1007/s11920-017-0767-9

8. Petruccelli K, Davis J, Berman T. Adverse childhood experiences and associated health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse Negl. 2019;97:104127. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104127

9. Mondelli V, Dazzan P. Childhood trauma and psychosis: moving the field forward. Schizophr Res. 2019;205:1–3. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2019.02.001

10. Brown RC, Heines S, Witt A, et al. The impact of child maltreatment on non-suicidal self-injury: data from a representative sample of the general population. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):181. doi:10.1186/s12888-018-1754-3

11. Duke NN, Pettingell SL, McMorris BJ, Borowsky IW. Adolescent violence perpetration: associations with multiple types of adverse childhood experiences. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):e778–86. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-0597

12. Nock MK. Why do people hurt themselves? New insights into the nature and functions of self-injury. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2009;18(2):78–83. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01613.x

13. Westlund Schreiner M, Klimes-Dougan B, Begnel ED, Cullen KR. Conceptualizing the neurobiology of non-suicidal self-injury from the perspective of the research domain criteria project. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;57:381–391. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.09.011

14. Lang CM, Sharma-Patel K. The relation between childhood maltreatment and self-injury: a review of the literature on conceptualization and intervention. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2011;12(1):23–37. doi:10.1177/1524838010386975

15. Nolen-Hoeksema S Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes; 1991.

16. Kim JS, Jin MJ, Jung W, Hahn SW, Lee SH. Rumination as a mediator between childhood trauma and adulthood depression/anxiety in non-clinical participants. Front Psychol. 2017;8:1597. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01597

17. Coleman SE, Dunlop BJ, Hartley S, Taylor PJ. The relationship between rumination and NSSI: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Psychol. 2022;61(2):405–443. doi:10.1111/bjc.12350

18. Seth D, Pollak RK, Joan E. P3b reflects maltreated children s r source psychophysiology so 2001 mar 38 2 267 74. Psychophysiology. 2001;38(2):267–274.

19. Disner SG, Beevers CG, Haigh EA, Beck AT. Neural mechanisms of the cognitive model of depression. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12(8):467–477. doi:10.1038/nrn3027

20. Selby EA, Franklin J, Carson-Wong A, Rizvi SL. Emotional cascades and self-injury: investigating instability of rumination and negative emotion. J Clin Psychol. 2013;69(12):1213–1227. doi:10.1002/jclp.21966

21. Taylor PJ, Jomar K, Dhingra K, Forrester R, Shahmalak U, Dickson JM. A meta-analysis of the prevalence of different functions of non-suicidal self-injury. J Affect Disord. 2018;227:759–769. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.073

22. Qu D, Wang Y, Zhang Z, et al. Psychometric Properties of the Chinese Version of the Functional Assessment of Self-Mutilation (FASM) in Chinese Clinical Adolescents. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:755857. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.755857

23. Pogge D, Handelsman L. Validity of the Childhood trauma questionnaire in an adolescent psychiatric population. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;2:2.

24. Cui Y, Kim SW, Lee BJ, et al. Negative schema and rumination as mediators of the relationship between childhood trauma and recent suicidal ideation in patients with early psychosis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80:3.

25. Wan Y, Chen J, Sun Y, Tao F. Impact of childhood abuse on the risk of non-suicidal self-injury in mainland Chinese adolescents. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0131239. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0131239

26. Lisa H, Glassmana MRW, Jill M. *Child maltreatment, non-suicidal self-injury, and the mediating role of self-criticism; 2008.

27. Chen Z, Li J, Liu J, Liu X. Adverse childhood experiences, recent negative life events, and non-suicidal self-injury among Chinese college students: the protective role of self-efficacy. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Ment Health. 2022;16(1):97. doi:10.1186/s13034-022-00535-1

28. Berthelot N, Paccalet T, Gilbert E, et al. Childhood abuse and neglect may induce deficits in cognitive precursors of psychosis in high-risk children. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2015;40(5):336–343. doi:10.1503/jpn.140211

29. Rodenas-Perea G, Velasco-Barbancho E, Perona-Garcelan S, et al. Childhood and adolescent trauma and dissociation: the mediating role of rumination, intrusive thoughts and negative affect. Scand J Psychol. 2023;64(2):142–149. doi:10.1111/sjop.12879

30. Rauschenberg C, van Os J, Cremers D, Goedhart M, Schieveld JNM, Reininghaus U. Stress sensitivity as a putative mechanism linking childhood trauma and psychopathology in youth’s daily life. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;136(4):373–388. doi:10.1111/acps.12775

31. Michael T, Halligan SL, Clark DM, Ehlers A. Rumination in posttraumatic stress disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2007;24(5):307–317. doi:10.1002/da.20228

32. Gianferante D, Thoma MV, Hanlin L, et al. Post-stress rumination predicts HPA axis responses to repeated acute stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;49:244–252. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.07.021

33. Ghazanfari F, Rezaei M, Rezaei F. The mediating role of repetitive negative thinking and experiential avoidance on the relationship between childhood trauma and depression. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2018;32(3):432–438. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2017.12.010

34. Ando A, Giromini L, Ales F, Zennaro A. A multimethod assessment to study the relationship between rumination and gender differences. Scandina J Psychol. 2020;61(6):740–750. doi:10.1111/sjop.12666

35. Johnson DP, Whisman MA. Gender differences in rumination: a meta-analysis. Pers Individ Dif. 2013;55(4):367–374. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2013.03.019

36. Shors TJ, Millon EM, Chang HY, Olson RL, Alderman BL. Do sex differences in rumination explain sex differences in depression? J Neurosci Res. 2017;95(1–2):711–718. doi:10.1002/jnr.23976

37. Sigurdardottir S, Halldorsdottir S, Bender SS. Consequences of childhood sexual abuse for health and well-being: gender similarities and differences. Scand J Public Health. 2014;42(3):278–286. doi:10.1177/1403494813514645

38. Leach LS, Christensen H, Mackinnon AJ, Windsor TD, Butterworth P. Gender differences in depression and anxiety across the adult lifespan: the role of psychosocial mediators. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008;43(12):983–998. doi:10.1007/s00127-008-0388-z

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.