Back to Journals » Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment » Volume 11

The low level of understanding of depression among patients treated with antidepressants: a survey of 424 outpatients in Japan

Authors Kudo S, Tomita T , Sugawara N , Sato Y, Ishioka M , Tsuruga K , Nakagami T, Nakamura K, Yasui-Furukori N, Katagani K

Received 3 August 2015

Accepted for publication 14 September 2015

Published 28 October 2015 Volume 2015:11 Pages 2811—2816

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S93657

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Wai Kwong Tang

Shuhei Kudo,1 Tetsu Tomita,1 Norio Sugawara,1,2 Yasushi Sato,1 Masamichi Ishioka,3 Koji Tsuruga,4 Taku Nakagami,5 Kazuhiko Nakamura,1 Norio Yasui-Furukori1

1Department of Neuropsychiatry, Graduate School of Medicine, Hirosaki University, Hirosaki, 2Aomori Prefectural Center for Mental Health and Welfare, Aomori, 3Department of Psychiatry, Hirosaki Aiseikai Hospital, Hirosaki, 4Department of Psychiatry, Aomori Prefectural Tsukushigaoka Hospital, Aomori, 5Department of Neuropsychiatry, Odate City General Hospital, Odate, Japan

Background: We used self-administered questionnaires to investigate the level of understanding of depression among outpatients who were administered antidepressants.

Methods: A total of 424 outpatients were enrolled in this study. We used an original self-administered questionnaire that consisted of eight categories: (A) depressive symptoms, (B) the course of depression, (C) the cause of depression, (D) the treatment plan, (E) the duration of taking antidepressants, (F) how to discontinue antidepressants, (G) the side effects of the antidepressants, and (H) psychotherapy. Each category consisted of the following two questions: “Have you received an explanation from the doctor in charge?” and “How much do you understand about it?” The level of understanding was rated on a scale of 0–10 (11 anchor points). The Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology Japanese version, Global Assessment of Functioning, and Clinical Global Impression – Severity scale were administered, and clinical characteristics were investigated.

Results: The percentages of participants who received explanations were as follows: 61.8% for (A), 49.2% for (B), 50.8% for (C), 57.2% for (D), 46.3% for (E), 28.5% for (F), 50.6% for (G), and 36.1% for (H). The level of understanding in participants who received explanations from their physicians was significantly higher compared with patients who did not receive explanations for all evaluated categories. Patient age, age at disease onset, and Global Assessment of Functioning scores were significantly associated with more items compared with the other variables.

Conclusion: Psychoeducation is not sufficiently performed. According to the study results, it is possible for patients to receive better psychoeducation and improve their clinical outcomes.

Keywords: depression, psychoeducation, antidepressant, questionnaire

Introduction

Worldwide, depression often attracts attention outside of clinical settings because of its high prevalence and its influence on the function and quality of life of patients with depression as well as its impact on society. Depression is a common and debilitating illness that results in functional disability, decreased quality of life, and increased health care costs.1 Depression is a chronic, long-term disease with a high recurrence rate. It is identified by specific symptoms that can last for weeks and damage the lives of patients. This disorder often leads to functional disability, which causes significant social, work, and family problems for patients.2

The World Mental Health Survey reported that approximately 5.5%–5.9% of respondents had experienced a depressive episode in the previous year.3 In a Japanese survey, Kawakami et al reported that the lifetime prevalence of depression diagnosed using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DMS)-IV is 3.0%, and the 12-month prevalence is 1.2%.4 According to the 2002–2003 World Mental Health Japan Survey, the lifetime prevalence of depression diagnosed using the DSM-IV is 6.7%, and the 12-month prevalence is 2.9%.5 Based on these two reports regarding the epidemiology of depression, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan announced that the number of patients with mood disorders had increased; there were 1,036,000 patients according to the 2011 report.6

Thus, treating depression is of great social importance, and many researchers continue to optimize treatments for patients with depression. However, there are several problems in treating patients with depression. First, the participation rate is low. Among patients with depression, only 18.1% have visited psychiatrists.5 Second, even if patients with depression are treated by physicians and start taking medication, it is difficult for them to continue taking medication to treat their depression. A previous study reported that only 44.3% of patients continued their antidepressant regimen for 6 months, and 63.1% of the patients who discontinued their antidepressants did so without consulting their physicians.7

For severe psychiatric disorders, psychoeducation has become standard treatment. Brown et al started the psychoeducation approach in psychiatry in the 1970s for the families of patients with schizophrenia.8 Kemp et al reported that “compliance therapy” was effective in improving adherence and outcomes in patients with schizophrenia.9 According to a psychoeducation study of patients with bipolar disorder, a brief psychoeducation intervention combined with a pharmacological intervention was more effective at improving subjective quality of life in patients than a pharmacological intervention alone.10 Similarly, many psychoeducation studies of patients with depression have demonstrated the effectiveness or importance of psychoeducation for patients with depression. For example, some studies have reported that psychoeducation improved antidepressant adherence11,12 and that psychoeducation decreased the symptoms of patients with depression13 and effectively prevented relapse.14,15 In a meta-analysis, Donker et al concluded that brief passive psychoeducation interventions could reduce patient symptoms.16 Brown et al suggested that providing key messages about antidepressants to patients at baseline improved their adherence to antidepressants (eg, “told what to do if there were questions”, “told how long to expect to take medicine”, “advised of how long side effects will last”, and “given advice on managing minor side effects”).17 These educational messages seemed to be important to patients with depression in clinical settings, but authors have reported that some patients received insufficient information.17

Thus, psychoeducation is important and effective, but the practical use of psychoeducation is low in clinical settings for the treatment of patients with depression. However, the actual prevalence of psychoeducation for patients with depression and the level of understanding of depression among patients with depression have not been deeply examined. In this study, we used a self-administered questionnaire to investigate the level of understanding of depression among outpatients who took antidepressants.

Methods

Participants

This study was conducted from February 2013 to October 2013. Participants were recruited according to the following inclusion criteria: (a) outpatients (b) who had experienced or were experiencing a depressive episode, and (c) who had taken antidepressants or were taking antidepressants. We excluded patients who could not complete the questionnaire evaluating their level of understanding depression as well as patients with severe dementia, mental retardation, and blindness. From an ethical standpoint, we excluded patients with severe depression if they were delusional, had suicidal ideations or were in substupor, because we thought that the questionnaire would be invasive for them. The study population was 352 and was determined using the G-power program with an impact size of 0.3, an α =0.05, and a power (1−β) =0.80 at a confidence level of 95%. A total of 480 outpatients were recruited, and 424 outpatients were enrolled. The percentage of responses was 88.3%. The study participants were outpatients at six hospitals in Aomori and Akita, Japan: Hirosaki University School of Medicine and Hospital, Seihoku Chuoh Hospital, Hirosaki Aiseikai Hospital, Kuroisi General Hospital, Mutsu General Hospital, and Odate City General Hospital.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hirosaki University Hospital, and written informed consent was obtained from the patients or their authorized representatives prior to study participation.

Measures

To assess the level of understanding of depression among participants, we used an original self-administered questionnaires consisting of eight categories: (A) depressive symptoms, (B) the course of depression, (C) the cause of depression, (D) the treatment plan, (E) the duration of taking antidepressants, (F) how to discontinue antidepressants, (G) the side effects of antidepressants, and (H) psychotherapy. Each category consisted of the following two questions: “Have you received an explanation from the doctor in charge?” and “How much do you understand about it?” The level of understanding was rated on a scale of 0–10 (11 anchor points); “I don’t know it at all” was rated as 0, and “I know it perfectly” was rated as 10.

We administered the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology Japanese version (QIDS-J) to evaluate the severity of depression. The reliability and validity of this instrument have been previously established.18,19

To evaluate their general function and illness severity, all participants were assessed with the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) and the Clinical Global Impression – Severity scale (CGI-S). The GAF uses a numerical scale (0–100) and is used by mental health clinicians and physicians to subjectively rate the social, occupational, and psychological functioning of adults. The CGI-S is commonly used to measure symptom severity, treatment response, and treatment efficacy in studies of patients with mental disorders. It uses a 7-point scale that requires the clinician to rate the severity of the patient’s illness at the time of assessment relative to the clinician’s past experience with patients with the same diagnosis. Considering the total clinical experience, a patient is assessed on the severity of mental illness at the time of rating as follows: 1, normal, not at all ill; 2, borderline mentally ill; 3, mildly ill; 4, moderately ill; 5, markedly ill; 6, severely ill; or 7, extremely ill.

From the patients’ medical records, we collected demographic data, diagnosis, age at onset, disease duration, duration of taking antidepressants, number of major depressive episodes and hospitalizations, and employment status. All participants were diagnosed based on the DSM-IV.

Statistical analysis

We defined and calculated understanding scores for each category from (A) to (H) according to the levels of understanding shown above, and each score was rated 0–10.

A unpaired t-test was used to compare the understanding scores for each item between the participants who answered “yes” and “no” for each item. To investigate the association between the level of understanding of each item and the demographic or clinical variables, we performed Pearson’s correlation analysis. We used Spearman’s rank correlation and a t-test for QIDS-J and the employment statuses of the patients, respectively. A P-value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. The data were analyzed using the PASW Statistics PC software for Windows, version 18.0.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Clinical and demographic characteristics of the participants

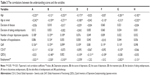

The study group consisted of 424 volunteers (134 males and 290 females), 56.1±16.9 years of age. Table 1 shows the clinical and demographic characteristics of the participants. In total, 364 patients (85.8%), 27 patients (6.4%), 10 patients (2.4%), and 10 patients (2.4%) met the DSM-IV criteria for major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, dysthymia, and personality disorder, respectively. The other 13 patients included four with panic disorder, three with anxiety disorder, three with adjustment disorder, two with eating disorder, and one with depressive disorder owing to systemic lupus erythematosus.

Receiving explanations about depression and understanding depression

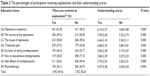

Table 2 shows the percentages of the participants who received explanations about depression and the results of the t-test correlating the understanding scores between the participants who received explanations for each item and the participants who did not. For the participants who received explanations, the results were 61.8% for item (A), 49.2% for item (B), 50.8% for item (C), 57.2% for item (D), 46.3% for item (E), 28.5% for item (F), 50.6% for item (G), and 36.1% for item (H). For all items, the understanding scores were significantly higher among the participants who received explanations compared with those did not receive explanations.

| Table 2 The percentages of participants receiving explanations and their understanding scores |

Correlations between the understanding scores and the variables

Table 3 shows Pearson’s correlation coefficients, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients and t-tests between the understanding scores for each item and the clinical and demographic variables. The patient’s age, age at onset, and GAF scores were significantly associated with more items (six to seven items) than with the other variables. The disease duration and duration of taking antidepressants were not significantly associated with any items. Item (E), which was significantly associated with fewer variables, was significantly associated with only QIDS-J.

A t-test was used to analyze the differences between the understanding scores between the two groups divided according to employment status. The averages of all items, including items (A), (B), (C), (D), (G), and (H), were higher for employees.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the level of understanding of depression among outpatients who took antidepressants. In total, the participants understood less than half of the education items, and less than half of the patients who took antidepressants understood depression or important items concerning taking antidepressants. We observed significant correlations between the understanding scores for the education items and the clinical or demographic variables. Employment status seemed to be significantly associated with many items, but there may have been covariance between employment and age, GAF, or other clinical characteristics, and the significance of employment status might be meaningless. This report is the first cross-sectional study to survey the level of understanding of depression among patients taking antidepressants and to report the correlations between psychoeducation about depression and clinical or demographic variables.

In this study, the rates of receiving explanations for items (F) and (E) (ie, “how to discontinue antidepressants” and “duration of taking antidepressants”), which were related to treatment discontinuation, were low and relatively low, respectively. Brown et al investigated patients with depression who received specific patient education, and the item “told how long to expect to take this medicine”, which was related to treatment discontinuation, was similarly low (29.2% at baseline).8 This result shows that the rate of receiving a message or explanation about discontinuing treatment remained low throughout the treatment period. We might involuntarily avoid explaining these items; therefore, we should intentionally explain this content during psychoeducation for patients with depression.

The results of this study are important in clinical psychiatry settings for patients who are taking antidepressants and who poorly understand depression or antidepressants. According to the correlation analysis, age and age at onset were negatively and significantly associated with many items, and the GAF score was positively and significantly associated with many items. In clinical settings, more substantial psychoeducation for patients who are older or who have lower GAF scores should be considered to assist patients with understanding depression or taking their antidepressants. In many previous studies, the effectiveness and importance of depression psychoeducation have been reported.13–16 Based on the results of this study, effective psychoeducation, along with understanding the characteristics of the patients, might be useful in clinical settings for patients who take antidepressants and who poorly understand depression or taking antidepressants.

We were unable to determine why there were significant correlations between the items and variables discussed above. The cognitive or memory function of the elderly patients might have influenced the results of significant correlation; elderly patients with lower cognitive or memory function might not be able remember the explanations they had received from their physicians. However, we did not investigate the cognitive functions of the participants. Although patients with higher GAF scores showed higher understanding scores, there was no explanation of whether the higher GAF score was the cause or result of a better understanding of depression. To clarify the association between age, age at onset or GAF score, and the level of understanding of depression, further prospective studies are required.

Some previous studies investigating the efficacy of depression psychoeducation or education have reported that the psychoeducation or education did not influence or improve the clinical outcomes of patients with major depressive disorders (ie, the remission, severity, or symptoms).20–22 Although Kutcher et al investigated the rate of participants who showed satisfaction (on a questionnaire) with the level of knowledge they received about depression and its treatment, their study did not assess the level of understanding of depression using objective or subjective scales.21 Considering the level of understanding depression among patients with major depressive disorders, patients would be able to obtain better clinical outcomes through more effective educational interventions based on the results from our study.

This study has several limitations. First, we evaluated only subjective measurements of the explanations of depression that the participants received from the physician in charge or the knowledge that they thought they had understood. The data lacked objective measurements of the level of understanding of depression. The present results might not reflect the factual level of the psychoeducation or explanation of depression that the patients had received. Second, in this study, we did not analyze the differences between the hospitals or the physicians in charge of the patients. The level of psychoeducation or explanation about depression might differ depending on the hospitals or the physicians in charge. More significant suggestions might be found by investigating these differences. Third, we investigated only Japanese patients. The humility of these patients may lower their understanding scores. In general, Japanese people are known to be humble. We must devise a means of improving psychoeducation by taking into account the regional or national characteristics of the patients.

Conclusion

We investigated the level of understanding of depression among patients taking antidepressants, and we showed the correlations between depression psychoeducation and the clinical or demographic variables of the patients. According to the results of this study, patients with depression could receive better psychoeducation and hence better therapeutic effects.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all their coworkers of this study for their skillful assistance in collecting and managing the data. This study was funded by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Research (JSPS, #20333734 and 15H04754), Mitsubishi Pharma Research Foundation, Asteras Schizophrenia Research Foundation, and a grant from the Hirosaki Research Institute for Neurosciences. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. Other remaining contributors declare that they have no competing interests.

Disclosure

Norio Yasui-Furukori has received grant/research support or honoraria from, and been a speaker of Asteras, Dainippon, Eli Lilly, GSK, Janssen-Pharma, Meiji, Mochida, MSD, Otsuka, Pfizer, Takada, and Yoshitomi. The other authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Egede LE. Major depression in individuals with chronic medical disorders: prevalence, correlates and association with health resource utilization, lost productivity and functional disability. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29(5):409–416. | ||

Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD, et al. The functioning and well-being of depressed patients. Results from the medical outcomes study. JAMA. 1989;262(7):914–919. | ||

Bromet E, Andrade LH, Hwang I, et al. Cross-national epidemiology of DSM-IV major depressive episode. BMC Med. 2011;9:90. | ||

Kawakami N, Shimizu H, Haratani T, Iwata N, Kitamura T. Lifetime and 6-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in an urban community in Japan. Psychiatry Res. 2004;121(3):293–301. | ||

Kawakami N, Takeshima T, Ono Y, et al. Twelve-month prevalence, severity, and treatment of common mental disorders in communities in Japan: preliminary finding from the World Mental Health Japan Survey 2002–2003. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59(4):441–452. | ||

Summary of Patient Survey 2011. Retrieved from http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/database/db-hss/sps_2011.html. Accessed November 27, 2011. | ||

Sawada N, Uchida H, Suzuki T, et al. Persistence and compliance to antidepressant treatment in patients with depression: a chart review. BMC Psychiatry. 2009;9:38. | ||

Brown GW, Birley JL, Wing JK. Influence of family life on the course of schizophrenic disorders: a replication. Br J Psychiatry. 1972;121(562):241–258. | ||

Kemp R, Hayward P, Applewhaite G, Everitt B, David A. Compliance therapy in psychotic patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 1996;312(7027):345–349. | ||

Cardoso Tde A, Farias Cde A, Mondin TC, et al. Brief psychoeducation for bipolar disorder: impact on quality of life in young adults in a 6-month follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Psychiatry Res. 2014;220(3):896–902. | ||

Wells KB, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, et al. Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283(2):212–220. | ||

Rost K, Nutting P, Smith J, Werner J, Duan N. Improving depression outcomes in community primary care practice: a randomized trial of the quEST intervention. Quality Enhancement by Strategic Teaming. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(3):143–149. | ||

Morokuma I, Shimodera S, Fujita H, et al. Psychoeducation for major depressive disorders: a randomised controlled trial. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210(1):134–139. | ||

Shimazu K, Shimodera S, Mino Y, et al. Family psychoeducation for major depression: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;198(5):385–390. | ||

Kronmüller KT, Victor D, Schenkenbach C, et al. Knowledge about affective disorders and outcome of depression. J Affect Disord. 2007;104(1–3):155–160. | ||

Donker T, Griffiths KM, Cuijpers P, Christensen H. Psychoeducation for depression, anxiety and psychological distress: a meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2009;7:79. | ||

Brown C, Battista DR, Sereika SM, Bruehlman RD, Dunbar-Jacob J, Thase ME. How can you improve antidepressant adherence? J Fam Pract. 2007;56(5):356–363. | ||

Fujisawa D, Nakagaw A, Tajima M, et al. Reliability and validity of Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology Japanese version. Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi. 2008;S324. Japanese. | ||

Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Ibrahim HM, et al. The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician Rating (IDS-C) and Self-Report (IDS-SR), and the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician Rating (QIDS-C) and Self-Report (QIDS-SR) in public sector patients with mood disorders: a psychometric evaluation. Psychol Med. 2004;34(1):73–82. | ||

Brook OH, van Hout H, Stalman W, et al. A pharmacy-based coaching program to improve adherence to antidepressant treatment among primary care patients. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(4):487–489. | ||

Kutcher S, Leblanc J, Maclaren C, Hadrava V. A randomized trial of a specific adherence enhancement program in sertraline-treated adults with major depressive disorder in a primary care setting. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2002;26(3):591–596. | ||

Mundt JC, Clarke GN, Burroughs D, Brenneman DO, Griest JH. Effectiveness of antidepressant pharmacotherapy: the impact of medication compliance and patient education. Depress Anxiety. 2001;13(1):1–10. |

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.