Back to Journals » International Journal of General Medicine » Volume 15

The Impact of Vitamin D Level on the Severity and Outcome of Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19 Disease

Authors AlKhafaji D, Al Argan R , Albaker W, Al Elq A , Al-Hariri M , AlSaid A, Alwaheed A , Alqatari S , Alzaki A , Alwarthan S, AlRubaish F, AlGuaimi H, Ismaeel F , Alsaeed N , AlElq Z, Zainuddin F

Received 25 October 2021

Accepted for publication 15 December 2021

Published 7 January 2022 Volume 2022:15 Pages 343—352

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S346169

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Dania AlKhafaji,1 Reem Al Argan,1 Waleed Albaker,1 Abdulmohsen Al Elq,1 Mohammed Al-Hariri,2 Abir AlSaid,1 Abrar Alwaheed,1 Safi Alqatari,1 Alaa Alzaki,1 Sara Alwarthan,1 Fatimah AlRubaish,1 Haya AlGuaimi,1 Fatema Ismaeel,1 Nidaa Alsaeed,1 Zainab AlElq,1 Fatma Zainuddin3

1Department of Internal Medicine, College of Medicine, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, King Fahd Hospital of the University, Khobar, Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia; 2Department of Physiology, College of Medicine, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Dammam, Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia; 3Department of Medical Allied Services, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, King Fahd Hospital of the University, Khobar, Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence: Mohammed Al-Hariri Tel +966507275028

Email [email protected]

Purpose: The world is experiencing a life-altering and extraordinary situation in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. There are limited data and controversies regarding the relationship between vitamin D (Vit D) status and COVID-19 disease. Thus, this study was designed to investigate the association between Vit D levels and the severity or outcomes of COVID-19 disease.

Methods: A cross-sectional observational study was conducted in the Eastern province of Saudi Arabia from January to August 2021. All the admitted patients who were diagnosed with COVID-19 infection were distributed into three groups depending on their Vit D levels: normal, insufficiency, and deficiency. For the three groups, demographic data, and laboratory investigations as well as data regarding the severity of COVID-19 were collected and analysed.

Results: A total of 203 diagnosed cases of COVID-19 were included in this study. The Vit D level was normal (> 30) in 31 (15.3%) cases, insufficient in 45 (22.2%) cases and deficient in 127 (62.6%) cases. Among the included cases, 58 (28.6%) were critical cases, 109 (53.7%) were severe and 36 (17.7%) had a mild-moderate COVID-19 infection. The most prevalent comorbidity of patients was diabetes mellitus 117 (57.6%), followed by hypertension 70 (34.5%), cardiac disease 24 (11.8%), chronic kidney disease 19 (9.4%) and chronic respiratory disease in 17 (8.4%) cases. Importantly, the current study did not detect any significant association between Vit D status and COVID-19 severity (p-value=0.371) or outcomes (hospital stay, intensive care units admission, ventilation, and mortality rate) (p-value > 0.05), even after adjusting the statistical model for the confounders.

Conclusion: In hospital settings, Vit D levels are not associated with the severity or outcomes of COVID-19 disease. Further, well‐designed studies are required to determine whether Vit D status provides protective effects against worse COVID-19 outcomes.

Keywords: vitamin D, COVID-19, severity, observational, Saudi Arabia

Introduction

During the last decade, vitamin D (Vit D) has maintained and attracted higher levels of interest in biomedical and health researchers more than all other micronutrients.1,2

It is well known that Vit D plays a vital role in the homeostasis of calcium and phosphate as well as in bone mineralization and skeletal development.3 In addition, recent research has established links between low levels of Vit D and various chronic disorders, such as autoimmune diseases, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, and malignancies.4

Vit D deficiency was highly prevalent in adult populations within Saudi Arabia.5 A meta-analysis conducted in 2018, which included a cumulative sample of 1910 participants, concluded that hypovitaminosis D among Saudi women of childbearing age had a prevalence of 77.4%.6 Importantly, the hot climate in Saudi Arabia limits outdoor activities during the day, and modern lifestyles focus on indoor sedentary activities, so Saudi adults often have a relatively low dietary intake of Vit D.7,8 This low intake of Vit D may be related to their frequent consumption of energy-dense foods, such as soft drinks and fast foods which are poor in Vit D,9 while they have low consumption of healthy foods that contain reasonable amounts of Vit D, such as fatty fish (tuna, salmon and mackerel)10 and dairy products fortified with Vit D.9,11 Additionally, sun avoidance is common in Saudi Arabia among women due to cultural reasons related to dress style, which tends to be usually dark and covers the entire body,12 and aesthetic choices, as women commonly use sun blockers, since they prefer fair skin rather than suntanned skin.13,14

The COVID-19 pandemic has killed millions and has led to the largest economic collapse around the globe.15 Therefore, an urgent need exists for therapeutic strategies to predict and understand risk factors for contracting the infection for better outcomes thereafter.

Locally, COVID-19 has infected a total of 547.262 patients with total mortality of 8.724 cases by the time of writing this paper (October 2021), according to the Saudi Ministry of Health registry.16

There are many established risk factors for COVID-19. Currently, Vit D status has been identified as a potentially achievable supplement in the treatment or prevention of COVID-19.17

The immunoregulatory properties of Vit D in respiratory viral infections are induced via enhancing the levels of virus-specific CD8+ T cells, C-X-C motif chemokine 10 and Interferon in respiratory epithelium, recruitment of immune cells to the site of infection, reducing viral replication strengthening of epithelial cell junction integrity and reducing the cytokine storm induced by the adaptive immune response as well as innate immune system.18,19

As aforementioned, some studies demonstrated a significant correlation between Vit D and COVID-19 cases and its related outcomes,18,20 while other studies did not find the correlation when confounding variables are adjusted.21,22 Yet, there is insufficient evidence on the association between COVID-19 severity or outcomes and Vit D levels.23

The effect of Vit D supplementation, however, was not established.24 A recent meta-analysis, which included a total of 25 randomized control studies, showed that intake of Vit D supplements decreased the possibility of having acute respiratory tract infections.25 The studies which continued to be carried out regarding role of Vit D in severity and outcomes of COVID-19 demonstrated that Vit D supplementation could reduce the severity of COVID-19 infection and boost the immune function in Vit D deficient patients.26

Nowadays, available data are controversial in this regard, and the most ideal regimen of supplementation advised has not yet been determined.27,28

The worldwide spread of the pandemic of COVID-19 infection has resulted in an increase in Vit D supplementation. This practice lacks adequate support of studies at the time being, mainly supported by speculations about presumed mechanisms of action.25 Therefore, the aim of the present study was to investigate the association between Vit D levels and the severity or outcomes of COVID-19 disease.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional observational study was conducted in King Fahd Hospital of the University in Al Khobar at Eastern province of Saudi Arabia from January to August 2021. All of the admitted patients who were diagnosed to have COVID-19 infection were recruited from the hospital records.

Diagnosis of COVID-19 infection was made based on the laboratory authority guidelines. “Swab samples were obtained from the patient’s oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal orifice/s. Sample investigations were performed by certified laboratory personnel following manufacturer’s recommendations for the defined cut-off cycle threshold (CT) value for each target gene, by using RNA using ViiA7 RT-PCR (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and Altona reagents. (Altona Diagnostics, Hamburg, Germany)”.29

All the recruited patient profiles were distributed into three groups depending on their Vit D level: “Vit D level ≥ 30 ng/mL (normal), Vit D level between 21–29 ng/mL (insufficiency) and Vit D level ≤ 20 ng/mL (deficiency)”.1,30 For the three groups, the following parameters were collected: 1) baseline data (age, gender); 2) laboratory investigations (Vit D, calcium, phosphorus, albumin, parathyroid hormone [PTH], white blood cell count [WBC] with neutrophils and lymphocyte count, creatinine level, C-reactive protein [CRP], ferritin, lactate dehydrogenase [LDH], D-dimer, erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR]); and 3) data regarding severity of COVID-19 that were then compared between the three groups and graded as a) mild-moderate disease, if there is no pneumonia signs on chest x-ray and no requirement for oxygen; b) severe disease reflected by any one of the followings: respiratory rate ≥ 30/minute, oxygen saturation ≤93% on room air, PaO2/FiO2 < 300 or lung infiltrates > 50% of the lung field within 24–48 hours; c) critical, if presenting any of followings: ARDS, sepsis, altered level of consciousness, multi-organ failure or with risk factors of cytokine storm syndrome if there is one or more of the followings: high D-dimer > 1mcg/mL, LDH > 250 U/L and ferritin > 600 ug/L.2

Informed consent form was obtained from all patients. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local Review Board in Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University (IRB-2020-01-265-2/6/2021).

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed by IBM SPSS.26. All categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages, while all continuous data was presented as median and IQR. A Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test was used to check the association between variables, and a Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare the medians. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed, all the confounding variables were adjusted, and odds ratios (ORs) with their 95% confidence intervals (CI) were measured. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

A total of 203 diagnosed cases of COVID-19 were included in this study. There were 115 (56.7%) males and 88 (43.3%) females. The mean age of patients was 56.8 (±15.4) years (range 20–93). The majority 85 (41.9%) of cases were aged 41–60 years, followed by 61–80 years 57 (28.1%), while 50 (24.6%) cases were 20–40 years and 11 (5.4%) cases were >80 years. The most prevalent comorbidity of patients was diabetes mellitus (DM) 117 (57.6%) followed by hypertension (HTN) 70 (34.5%), cardiac disease 24 (11.8%), chronic kidney disease 19 (9.4%), chronic respiratory disease in 17 (8.4%) cases.

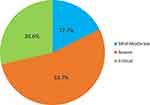

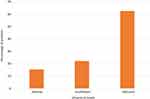

Among the included cases, 58 (28.6%) were critical cases, 109 (53.7%) were severe and 36 (17.7%) had a mild-moderate COVID-19 infection (Figure 1). The Vit D level was normal (>30) in 31 (15.3%) cases, insufficient in 45 (22.2%) cases and deficient in 127 (62.6%) cases (Figure 2).

|

Figure 1 Percentage of patients according to the severity of COVID-19 disease. |

|

Figure 2 Percentages of patients with different Vit D levels. |

A comparison of laboratory parameters between Vit D levels is presented in Table 1. WBC, neutrophil and Cl were significantly higher in cases with Vit D deficiency (p-values < 0.05), while ESR was significantly higher in cases with normal Vit D levels (p-values < 0.05). All other parameters were statistically similar in all groups.

|

Table 1 Comparison of Laboratory Parameters Between COVID-19 Groups Based on Vit D Level |

The association between severity of COVID-19 with age, gender, comorbidities and Vit D level is shown in Table 2. The increasing age of the cases was significantly associated with critical or severe COVID-19 (p-value < 0.001). Males, diabetes mellitus and cases with deficiency Vit D levels were significantly associated with critical or severe COVID-19 (p-values <0.05). However, cases with Vit D deficiency were insignificantly associated with severity (p = 0.20).

|

Table 2 Univariate Analysis of Association Between Severity of COVID-19 with Age, Gender, Co-Morbidities and Vit D Insufficiency and Deficiency |

Table 3 depicts the associated outcomes of COVID-19 with gender, age and comorbidities and Vit D deficiencies. COVID-19 cases with an age group >40 years and with hypertension had a significantly longer duration of hospitalization (p-value=0.05), while mechanical ventilator was required in cases with older age (>40 years) and diabetes mellitus cases (p-values < 0.05). As expected, the present study showed that the mortality rate was significantly higher in cases with higher age, HTN and cardiac disease (p-values < 0.05).

|

Table 3 Univariate Analysis of Association Between Outcome of COVID-19 with Age, Gender, Comorbidities and Vit D Insufficiency and Deficiency |

The current study failed to find any significant association (p-value=0.371) between Vit D levels with the severity of COVID-19. Similar profiles were observed between Vit D levels with the COVID-19 outcomes (hospital stay, ICU admission, ventilation, and mortality rate) (p-value > 0.05), as presented in Table 4.

|

Table 4 Univariate Analysis of Association Between Severity and Outcome of COVID-19 and Vit D Level |

In multivariate analysis, the model was first adjusted for Vit D then gender, age, and co-morbidities. In this model, increasing age was significantly associated with both severe (OR 2.85; p = 0.02) and critical (OR 4.8; p = 0.005) COVID-19 cases. Gender, comorbidities and Vit D deficiencies were insignificantly associated with critical or severe COVID-19. Association between ICU admission and all the variables was insignificant. Meanwhile, cases with increasing age and diabetic patients were significantly associated with ventilation (ORs 8.3 and 2.9; ps = 0.016 and 0.03 respectively), and mortality was significantly higher in hypertensive and cases with cardiac disease (ORs 4.8 and 4; ps = 0.003 and 0.012 respectively), as shown in Table 5.

|

Table 5 Multivariate Analysis of Association Between Severity and Outcome of COVID-19 with Age, Gender, Co-Morbidities and Vit D Insufficiency and Deficiency |

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, few studies have evaluated the impact of Vit D status on the severity and outcome of COVID-19 disease in Saudi Arabia. In our patients, we did not find an association between Vit D status and COVID-19 severity or better outcomes. Moreover, when we adjusted the statistical model for gender, age and comorbidities, Vit D level was not associated with the course of the disease.

The current study’s findings are supported by a similar study that did not prove the relation between Vit D level and COVID-19 severity or outcomes. The two largest sample Mendelian randomization (cohort and genetic) approaches conducted among 443.734 participants, from 11 courtiers, failed to promote any relevance between COVID-19 severity or outcomes and Vit D.24 Further, a study on 341.484 participants found insufficient evidence to support the potential link between Vit D level and COVID-19 infection severity and mortality after adjustment for confounders.31

At the same point, another multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial conducted on 240 patients with severe COVID-19 did not prove any significant relevant COVID-19 outcomes, independent of the ability of Vit D therapy to correct serum 1–25-hydroxy Vit D level.32 The same findings have been reported by other researchers who found that a single high dose of Vit D (540,000 IU) during the early phase of critical illness rapidly corrected serum Vit D level but did not promote the clinical outcomes of COVID-19 infection compared with the placebo. Furthermore, research on 502,624 infected patients with COVID-19 failed to detect an association between risk of COVID-19 infection and Vit D level.21

Low Vit D status is common among Saudi women,6,33 while recent reports showed that males accounted for the higher prevalence of COVID-19 cases in Saudi Arabia.34,35 This discrepancy indicates weakness in the direct relation between Vit D status and COVID-19 infection.

In contrast, our results are in disagreement with those of other reports. A local study reported that Vit D deficiency was found to be a predictor for COVID-19 mortality; at the same time, this study failed to find a significant association between Vit D status with COVID-19 infection.36 However, this study did not adjust for other comorbidities while running the statistical tests. A study conducted in India found a lower level of Vit D in severe COVID-19 patients.37 However, this study did not define the criteria for severity. In our work, we had assessed the severity of COVID-19 based on well-reported clinical and paraclinical parameters.2

Another local study conducted on only 109 COVID-19 participants “Group 1: control; Group 2: 35 ICU patients with COVID-19; and Group 3: 74 COVID-19 patients in the non-ICU department,” concluded that a higher risk of COVID-19 disease was significantly associated with a low level of Vit D. However, this small study did not define the low level of Vit D and did not control the confounders.38

According to researchers, the reported relationship between Vit D level and the severity or mortality of COVID-19 infection may be confounded due to factors difficult to manage for even with advanced statistical adjustments, such as quality of health services, socioeconomic status, or preexisting medical comorbidities associated with lower Vit D status,24,31 as well as the reverse causation bias accompanied the rapid publication process24 and the small sample size or unblinded intervention.27 Even the Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition could not find sufficient facts to recommend Vit D supplementation in patients with acute pulmonary infection.39

The relationship between Vit D level and viral infection was well reported.40 Several observational studies have shown a positive association between Vit D deficiency or insufficiency and COVID-19 infection severity or better outcomes.41,42 One of the hallmarks of COVID-19 infection severity is the huge secretion of inflammatory cytokines known as a “cytokine storm”.43 According to a previous report showing that respiratory illnesses are associated with dysregulated Vit D metabolism, suggesting the possibility of Vit D deficiency as a consequence of pulmonary inflammation.44

CRP is a sensitive non-specific biomarker of the acute-phase response in infection, inflammation and tissue damage that could be utilized as an inflammation indicator.45 Our data did not detect higher concentrations of CRP in the Vit D deficiency group when compared to the other two groups. However, this observation can be explained either by the fact that an elevated level of CRP could be seen mainly in the early stages of COVID19 infection in non-severe individuals and before the medical intervention,46,47 or due to the effect of sample size and other preexisting comorbidities on results.27,48

Since the onset of the COVID-19 infection outbreak, various research has been published, and there have been more meta-analyses and systematic reviews on the available evidence on the course of the disease and its related risk factors, but all previous researches have concluded that there is still a lack of strong evidence to support the direct role of Vit D and the severity or outcomes of COVID‐19 infection.49

Limitation

The results of the current study need to be interpreted with few limitations. First, the number of patients is small, and as a study from a single center, this limits the generalizability of our results. Second, only inpatients were enrolled in the study, and it would be helpful to evaluate the relationship of Vit D level with other outpatient outcomes and risks.

Conclusion

In hospital settings, Vit D levels are not associated with the severity or outcomes of COVID-19 disease. Further well‐designed studies are required to determine whether Vit D status provides protective effects against worse COVID-19 outcomes.

Data Sharing Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Al-Daghri NM. Vitamin D in Saudi Arabia: prevalence, distribution and disease associations. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2018;175:102–107. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2016.12.017

2. Alkerwi A, Sauvageot N, Gilson G, Stranges S. Prevalence and correlates of vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency in Luxembourg adults: evidence from the observation of cardiovascular risk factors (ORISCAV-LUX) study. Nutrients. 2015;7(8):6780–6796. doi:10.3390/nu7085308

3. Palacios C. The role of nutrients in bone health, from A to Z. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2006;46(8):621–628. doi:10.1080/10408390500466174

4. Rabenberg M, Scheidt-Nave C, Busch MA, Rieckmann N, Hintzpeter B, Mensink GBM. Vitamin D status among adults in Germany - results from the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS1) chronic disease epidemiology. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:641. doi:10.1186/s12889-015-2016-7

5. Al-Daghri NM, Aljohani N, Al-Attas OS, et al. Dairy products consumption and serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level in Saudi children and adults. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8(7):8480.

6. Alzaheb RA. The prevalence of hypovitaminosis D and its associated risk factors among women of reproductive age in Saudi Arabia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Med Insights Womens Health. 2018;3:1179562X18767884. doi:10.1177/1179562x18767884

7. Zareef TA, Jackson RT, Alkahtani AA. Vitamin D intake among premenopausal women living in Jeddah: food sources and relationship to demographic factors and bone health. J Nutr Metab. 2018;2018:1–13. doi:10.1155/2018/8570986

8. Al-Hariri MT, Goweiz R, Aldhafery B, et al. Potential cause affecting bone quality in Saudi Arabia: new insights. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2021;10(1):533. doi:10.4103/JFMPC.JFMPC_1872_20

9. Hammad LF, Benajiba N. Lifestyle factors influencing bone health in young adult women in Saudi Arabia. Afr Health Sci. 2017;17(2):524–531. doi:10.4314/AHS.V17I2.28

10. Lu Z, Chen TC, Zhang A, et al. An evaluation of the vitamin D3 content in fish: is the vitamin D content adequate to satisfy the dietary requirement for vitamin D? J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;103(3–5):642–644. doi:10.1016/J.JSBMB.2006.12.010

11. Itkonen ST, Erkkola M, Lamberg-Allardt CJE. Vitamin D fortification of fluid milk products and their contribution to vitamin D intake and vitamin D status in observational studies—a review. Nutrients. 2018;10(8):1054. doi:10.3390/nu10081054

12. Kanan RM, Al Saleh YM, Fakhoury HM, Adham M, Aljaser S, Tamimi W. Year-round vitamin D deficiency among Saudi female out-patients. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(3):544–548. doi:10.1017/S1368980012002947

13. Alzaheb RA, Al-Amer O. Prevalence and predictors of hypovitaminosis D among female university students in Tabuk, Saudi Arabia. Clin Med Insights Womens Health. 2017;10:1179562X1770239. doi:10.1177/1179562X17702391

14. Al-Raddadi R, Bahijri S, Borai A, AlRaddadi Z. Prevalence of lifestyle practices that might affect bone health in relation to vitamin D status among female Saudi adolescents. Nutrition. 2018;45:108–113. doi:10.1016/J.NUT.2017.07.015

15. McKee M, Stuckler D. If the world fails to protect the economy, COVID-19 will damage health not just now but also in the future. Nat Med. 2020;26:640–642. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0863-y

16. World Health Organization. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/region/emro/country/sa.

17. Mansur JL, Tajer C, Mariani J, Inserra F, Ferder L, Manucha W. Vitamin D high doses supplementation could represent a promising alternative to prevent or treat COVID-19 infection. Clin e Investig En Arterioscler. 2020;32(6):267–277. doi:10.1016/j.arteri.2020.05.003

18. Grant WB, Lahore H, McDonnell SL, et al. Evidence that vitamin D supplementation could reduce risk of influenza and COVID-19 infections and deaths. Nutrients. 2020;12(4):988. doi:10.3390/NU12040988

19. Teymoori-Rad M, Shokri F, Salimi V, Marashi SM. The interplay between vitamin D and viral infections. Rev Med Virol. 2019;29(2):e2032. doi:10.1002/RMV.2032

20. De Smet D, De Smet K, Herroelen P, Gryspeerdt S, Martens GA. Serum 25(OH)D level on hospital admission associated with COVID-19 stage and mortality. Am J Clin Pathol. 2021;155(3):381–388. doi:10.1093/AJCP/AQAA252

21. Hastie CE, Mackay DF, Ho F, et al. Vitamin D concentrations and COVID-19 infection in UK Biobank. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. 2020;14(4):561–565. doi:10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050

22. Darling AL, Ahmadi KR, Ward KA, et al. Vitamin D concentration, body mass index, ethnicity and SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19: initial analysis of the first- reported UK Biobank Cohort positive cases (n 1474) compared with negative controls (n 4643). Proc Nutr Soc. 2021;80(OCE1):7. doi:10.1017/S0029665121000185

23. Ali N. Role of vitamin D in preventing of COVID-19 infection, progression and severity. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13(10):1373–1380. doi:10.1016/J.JIPH.2020.06.021

24. Butler-Laporte G, Nakanishi T, Mooser V, et al. Vitamin D and COVID-19 susceptibility and severity in the COVID-19 host genetics initiative: a Mendelian randomization study. PLoS Med. 2021;18(6):e1003605. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1003605

25. Panfili FM, Roversi M, D’Argenio P, Rossi P, Cappa M, Fintini D. Possible role of vitamin D in Covid-19 infection in pediatric population. J Endocrinol Invest. 2021;15:1–9. doi:10.1007/s40618-020-01327-0

26. Honardoost M, Ghavideldarestani M, Khamseh ME. Role of vitamin D in pathogenesis and severity of COVID-19 infection. Arch Physiol Biochem. 2020;30:1–7. doi:10.1080/13813455.2020.1792505

27. Entrenas Castillo M, Entrenas Costa LM, Vaquero Barrios JM, et al. Effect of calcifediol treatment and best available therapy versus best available therapy on intensive care unit admission and mortality among patients hospitalized for COVID-19: a pilot randomized clinical study. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2020;203:105751. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2020.105751

28. Murai IH, Fernandes AL, Sales LP, et al. Effect of a single high dose of vitamin D3 on hospital length of stay in patients with moderate to severe COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;325(11):1053–1060. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.26848

29. Public Health Authority. Laboratory diagnosis. Available from: https://covid19.cdc.gov.sa/professionals-health-workers/laboratory-diagnosis/.

30. Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(7):1911–1930. doi:10.1210/JC.2011-0385

31. Hastie CE, Pell JP, Sattar N. Vitamin D and COVID-19 infection and mortality in UK Biobank. Eur J Nutr. 2021;60(1):545–548. doi:10.1007/s00394-020-02372-4

32. Murai IH, Fernandes AL, Sales LP, et al. Effect of vitamin D3 supplementation vs placebo on hospital length of stay in patients with severe COVID-19: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized controlled trial. medRxiv. 2020. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.26848

33. Al-Alyani H, Al-Turki HA, Al-Essa ON, Alani FM, Sadat-Ali M. Vitamin D deficiency in Saudi Arabians: a reality or simply hype: a meta-analysis (2008–2015). J Family Community Med. 2018;25(1):1–4. doi:10.4103/jfcm.JFCM_73_17

34. Alyami MH, Naser AY, Orabi MAA, Alwafi H, Alyami HS. Epidemiology of COVID-19 in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: an ecological study. Front Public Health. 2020;8:506. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2020.00506

35. Alahmari AA, Khan AA, Elganainy A, et al. Epidemiological and clinical features of COVID-19 patients in Saudi Arabia. J Infect Public Health. 2021;14(4):437–443. doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2021.01.003

36. Alguwaihes AM, Sabico S, Hasanato R, et al. Severe vitamin D deficiency is not related to SARS-CoV-2 infection but may increase mortality risk in hospitalized adults: a retrospective case–control study in an Arab Gulf country. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2021;33(5):1415. doi:10.1007/S40520-021-01831-0

37. Jain A, Chaurasia R, Sengar NS, Singh M, Mahor S, Narain S. Analysis of vitamin D level among asymptomatic and critically ill COVID-19 patients and its correlation with inflammatory markers. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1–8. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-77093-z

38. Al-Harbi S, Al-Harbi YA, Ezzat Abdellatif A, Al-Ahmadey ZZ, Alahmadi S. Retrospective evaluation of the serum level of vitamin D among COVID-19 patients in Al Madinah, Saudi Arabia. Biotechnol Biochem Res. 2021;9(1):8–13. doi:10.30918/BBR.91.21.018

39. GOV.UK. SACN rapid review: vitamin D and acute respiratory tract infections. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/sacn-rapid-review-vitamin-d-and-acute-respiratory-tract-infections.

40. Cannell JJ, Vieth R, Umhau JC, et al. Epidemic influenza and vitamin D. Epidemiol Infect. 2006;134(6):1129–1140. doi:10.1017/S0950268806007175

41. Carpagnano GE, Di Lecce V, Quaranta VN, et al. Vitamin D deficiency as a predictor of poor prognosis in patients with acute respiratory failure due to COVID-19. J Endocrinol Invest. 2021;44(4):765–771. doi:10.1007/s40618-020-01370-x

42. Mercola J, Grant WB, Wagner CL. Evidence regarding vitamin d and risk of covid-19 and its severity. Nutrients. 2020;12(11):3361. doi:10.3390/nu12113361

43. Mahmudpour M, Roozbeh J, Keshavarz M, Farrokhi S, Nabipour I. COVID-19 cytokine storm: the anger of inflammation. Cytokine. 2020;133:155151. doi:10.1016/j.cyto.2020.155151

44. Jolliffe DA, Stefanidis C, Wang Z, et al. Vitamin d metabolism is dysregulated in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(3):371–382. doi:10.1164/rccm.201909-1867OC

45. Pepys MB, Hirschfield GM. C-reactive protein: a critical update. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(12):1805–1812. doi:10.1172/JCI18921

46. Ali N. Elevated level of C‐reactive protein may be an early marker to predict risk for severity of COVID‐19. J Med Virol. 2020;92(11):2409–2411. doi:10.1002/JMV.26097

47. Ali A, Noman M, Guo Y, et al. Myoglobin and C-reactive protein are efficient and reliable early predictors of COVID-19 associated mortality. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1). doi:10.1038/S41598-021-85426-9

48. Kruit A, Zanen P. The association between vitamin D and C-reactive protein levels in patients with inflammatory and non-inflammatory diseases. Clin Biochem. 2016;49(7–8):534–537. doi:10.1016/J.CLINBIOCHEM.2016.01.002

49. Gibson-Moore H. Vitamin D: what’s new a year on from the COVID-19 outbreak? Nutr Bull. 2021;46(2):195–205. doi:10.1111/nbu.12499

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.