Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

The Effect of Teacher Discrimination Behavior on Adolescent Suicidal Ideation: A Cross-Sectional Survey

Authors Jiang MM , Chen JN, Huang XC, Zhang YL, Zhang JB , Zhang JW

Received 29 May 2023

Accepted for publication 7 July 2023

Published 17 July 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 2667—2680

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S420978

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Mei-Chun Cheung

Mao-Min Jiang,1,* Ji-Neng Chen,2,* Xin-Cheng Huang,3,* Yi-Lin Zhang,4 Jia-Bo Zhang,5 Jia-Wen Zhang6

1School of Public Affairs, Xiamen University, Xiamen, People’s Republic of China; 2Graduate School, St.Paul University Philippines, Tuguegarao, Philippines; 3School of Economics and Management, Beijing Institute of Graphic Communication, Beijing, People’s Republic of China; 4School of Humanities, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou, People’s Republic of China; 5School of Literature and Media, Lingnan Normal University, Zhanjiang, People’s Republic of China; 6School of Education, Silliman University, Dumaguete, 6200, Philippines

*These authors contributed equally to this work

Correspondence: Jia-Bo Zhang; Jia-wen Zhang, Email [email protected]; [email protected]

Introduction: Suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior, as the most severe psychological and behavioral problems among adolescents, bring not only significant damage to individual social functioning but also cause enormous economic and social pressure, which will ultimately be detrimental to social development and social stability. This paper aimed to explore the potential relationship between teacher discrimination behavior, peer bullying victimization, anxiety disorders, and adolescent suicidal ideation based on the Vulnerability-Stress Model.

Methods: From September to November 2022, our research team surveyed 21,017 junior high school students from 12 secondary schools in ten cities in China. Mplus 8.3 software was used to analyze the pathways of teacher discrimination behavior on adolescent suicidal ideation.

Results: The results showed that teacher preference had a significant negative effect on suicidal ideation, and teacher prejudice significantly positively affected suicidal ideation. Mediation test results indicated that there were significant independent mediating effects of peer bullying victimization and anxiety disorders between teacher discrimination behavior and adolescents’ suicidal ideation, as well as significant chain mediating effects.

Conclusion: Secondary school teachers should improve their self-quality and pay more attention to adolescents’ suicidal ideation. Teachers are expected to put love into their education, respect and trust each student, and attend to their emotional needs unbiasedly. Educators should develop targeted prevention and intervention measures according to the actual situation of school bullying and also strengthen adolescents’ life-value education to improve the psychological quality of adolescents and create a healthy campus atmosphere.

Keywords: teacher discrimination behavior, peer bullying victimization, anxiety disorders, suicidal ideation, adolescents

Introduction

The high prevalence and high risk of psychological problems among adolescents have received ongoing attention from governments, societies, and mental and medical communities. Suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior, as the most severe psychological and behavioral problems among adolescents, not only significantly damage individual social functioning but also cause severe economic and social pressure, which are detrimental to social development and stability.1–3 Studies have shown that suicide has become the second most important factor causing adolescent death.4,5 Furthermore, each year, more than 800,000 people die by suicide worldwide, estimated that between 10 and 20 million more people attempt suicide.6 According to 2019 data from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 18.8% of American high school students have considered suicide, and 2019 data from the Canadian Health Statistics Agency shows that about 12.7% of young people aged 15 to 24 have considered suicide in the past year Have considered suicide. Australian Department of Health figures show that about 15.6% of 15- to 19-year-olds have considered suicide. At the same time, some studies have shown that suicide ideation among adolescents has increased compared with pre-COVID-19 levels. The new crown epidemic has led to a series of factors, such as school closures, social isolation, and increased psychological stress, which may have affected the psychological status and suicidal tendencies of some adolescents.7 Suicidal ideation is a psychological activity in which an individual has suicidal thoughts due to an event or a particular reason, with some occasional and secretive nature.8 Meanwhile, on the one hand, suicidal ideation is a motivation for suicidal factors and a risk for suicidal behavior. On the other hand, suicidal ideation can predict suicide and is a critical factor in preventing suicidal behavior in adolescents to help further prevent and intervene in suicidal behavior.9 The stress vulnerability model suggests that stressors, individual qualities, and protective factors can jointly contribute to suicidal ideation.10 The cumulative ecological risk theory also proposes that adolescents’ ecological risk is vulnerable to the family and campus environments.11,12 Thus, this study aims to explore the paths of teacher discrimination behavior on adolescent suicidal ideation based on the campus ecological environment. Teacher prejudice and peer bullying victimization are stressors, anxiety disorders are individual qualities, and teacher preference is a protective factor, providing a reference for effectively preventing adolescent suicidal behavior.

The ecological systems theory emphasizes the influence of the environment on individual development and considers that the development of an individual is the result of interaction with the external environment.13,14 Adolescents’ ideological development and knowledge accumulation cannot be separated from the school environment. Previous studies have shown that a harmonious school environment, good teacher-student relationships, and close peer relationships are vital to improving adolescents’ emotional functioning and adaptive capacity.15,16 Adolescents are at an age when their ideology is weak, and they will subconsciously imitate and learn from teachers; thus, teachers’ behavior has an important impact on adolescents’ physical and mental health.17 Therefore, this requires teachers to treat each student fairly and justly and should not treat students differently based on their preferences. Teachers’ differential treatment of students is also known as teacher discrimination behavior. It mainly refers to teachers who show emotional or behavioral differentiation in their usual teaching and interactions with students.18 Typically, this type of behavior is generally the result of teachers’ inherent perceptions or attitudes based on students’ family background, learning, performance at school, and personality traits, which in turn leads to differential treatment19 and is mainly manifested by preference, discrimination, or suppression of students.20 Related studies have also found that the suicide rate of adolescents who frequently being punished by their teachers is two to three times higher than those who have never been subjected to such incidents. Based on this, this study will examine the impact of teacher discrimination behavior on adolescent suicide.

Peer bullying victimization refers to the physical and verbal aggression and aggression in social relationships students experience on campus from their peers.21 A study found that exposure to discrimination and humiliation were essential factors influencing suicidal ideation among secondary school students.22 The study noted that the more physical aggression male students suffered, the more likely they were to have suicidal ideation, while female students were more likely to have suicidal ideation due to the more verbal aggression and ostracism they suffered. In addition, secondary school students who had suffered peer bullying had a higher detection rate of suicidal ideation than those who had not experienced it.23–25 There are many causes of peer bullying victimization, including inadequate personal physical and mental development, teacher discriminatory behavior, unreasonable educational practices, and negative social impacts, among which teacher discriminatory behavior is one of the most important factors.26 The theory of cognitive development suggests that teachers’ words and behaviors influence the cognitive behavior of students. When teachers are biased and discriminate against students, it will inevitably lead to peer bullying and victimization of students.27 In turn, the victimization of students by their teachers and peers will inevitably produce an experience of frustration or shame, which triggers a sense of distress and suicidal ideation.28,29 Therefore, this study will also explore the potential mediating role of peer bullying victimization in the relationship between teacher discrimination behavior and adolescent suicidal ideation.

An integrative theory of motivation and volition suggests that suicidal ideation cannot be formed without adverse life events, unfavorable life circumstances, and sensitive psychological traits.30 However, suicidal ideation is also persistent and cumulative. As the negative environment spreads, the more anxiety and depression an individual develops, the more suicidal ideation is formed.31,32 Anxiety disorders are derived from the evolutionary theory of depression and refer to the negative emotions that arise due to the oppression of social status, identity, and the environment in which one lives, which are also the negative factors that seriously affect the physical and mental health development of adolescents.33 Previous studies have found that the more severe anxiety an individual experiences, the more likely it is to lead to depression or suicidal ideation.34,35 Adolescents who suffer from teacher discrimination and peer bullying in school are more likely to develop negative emotions and anxiety disorders.36,37 The theoretical model of self-injury also suggests that if adolescents face the discomfort of loneliness and low self-esteem due to tremendous stress, they are more likely to develop anxiety and depression after self-regulation failure, which increases the risk of suicidal behavior.38 Based on this, this study proposed a mediating role of anxiety disorders between teacher discrimination behavior, peer bullying victimization, and adolescent suicidal ideation.

What is the relationship between teacher discrimination behavior and adolescent suicidal ideation? Are there mediating effects of peer bullying victimization and anxiety disorders between teacher discrimination behavior and adolescents’ suicidal ideation? Based on the existing theoretical foundation and literature, the research hypotheses are shown in Figure 1: H1-1) teacher preference is negatively associated with adolescent suicidal ideation; H1-2) teacher prejudice is positively associated with adolescent suicidal ideation; H2-1) there is a potential mediating role of peer bullying victimization in the association between teacher preference and adolescent suicidal ideation; H2-2) there is a potential mediating role of peer bullying victimization in the association between teacher prejudice and adolescent suicidal ideation; H3-1) a potential mediating effect of anxiety disorders in the association between teacher preference and adolescent suicidal ideation; H3-2) a potential mediating effect of anxiety disorders in the association between teacher prejudice and adolescent suicidal ideation; H4-1) a chain-mediating effect of peer bullying victimization and anxiety disorders in the association between teacher preference and adolescent suicidal ideation; H4-2) a chain-mediating effect of peer bullying victimization and anxiety disorders had a mediating effect in the association between teacher prejudice and adolescent suicidal ideation.

Materials and Methods

Participants

From September to November 2022, a multi-stage sampling method was used to select 12 junior high schools in ten cities in the eastern, central, and western regions of China, including Xiamen City, Fujian Province (1), Lianyungang City, Jiangsu Province (2), Yantai City, Shandong Province (1), Xuancheng City, Anhui Province (2), Changzhi City, Shanxi Province (1), Xinxiang City, Henan Province (1), Xi’an City, Shaanxi Province (1), Zigong City, Sichuan Province (1), Mianyang City, Sichuan Province (1), Tianshui City, Gansu Province (1). One to two surveyors or survey teams were assigned to each school, and all members received online training to ensure they were clear about the meaning of the questionnaire and how to fill it out to reduce bias and errors caused by the surveyors. A total of 22,368 questionnaires were distributed, with 21,017 valid questionnaires and an effective rate of 93.96%. According to the formula  ,

,  , N is the total number of students in junior high schools in China, a total of 50,184,373, n=21,025. Then according to

, N is the total number of students in junior high schools in China, a total of 50,184,373, n=21,025. Then according to  , Z =1.96, P =0.5, This results in a sample error e of 0.68%. The survey was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kangda College of Nanjing Medical University (2022–01), and written consent was obtained from the surveyed students and their parents. The study follows the Declaration of Helsinki.

, Z =1.96, P =0.5, This results in a sample error e of 0.68%. The survey was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kangda College of Nanjing Medical University (2022–01), and written consent was obtained from the surveyed students and their parents. The study follows the Declaration of Helsinki.

Measures

Teacher Discrimination Behavior (TDB)

Teacher discrimination behavior is mainly measured through students’ emotional bias, equal opportunity, and behavioral orientation in daily school life. By integrating the Teacher Expectation Model proposed by Brophy and Good,39 Weinstein’s Teacher Treatment Scale,40 and Babad’s Teacher Behavior Questionnaire,41 the present study constructed the Teacher Differential Behavior Scale. The scale consists of two parts: teacher preference and teacher prejudice. The teacher preference scale consists of 9 questions (including: “My teacher always subconsciously influences me to excel”, “My punishment is fair and appropriate”, and “When things are not going my way, I can feel that my teacher was trying to encourage me and give me some comfort”, “If I was faced with a difficult task, I could feel support from my teachers”, “My teachers tried to encourage me to be the best”, “Teachers always show me that they love me”, “Teachers respect my opinions”, “I feel a sense of warmth, consideration, and affection with my teachers”, “teachers tolerate me having a different opinion from theirs”.) and the teacher prejudice scale also consisted of 9 questions (“Teachers often punish me more than I deserve”, “I am embarrassed by teachers spouting things I have said or done in front of others”. “I am often used as a “scapegoat” or black sheep by teachers at school”, “Teachers have punished me for no reason”, “Teachers often tell me they do not like my performance at school”. “Teachers have punished me for no reason”, “Teachers often tell me they do not like my performance at school”, “Teachers often criticized me in front of others for being lazy and useless”, “If something happened, I was often the only one to blame among my classmates”, “Teachers often treated me in a way that embarrasses me”, and “Teachers often lose their temper with me when I do not know why”.) Using a 7-point scale (1=strongly disagree, 7=strongly agree), the total score for each scale ranged from 9 to 63, with higher scores indicating higher levels of teacher preference or teacher prejudice.

Peer Bullying Victimization (PBV)

The Delaware Bullying Victimization Scale-Student (DBVS-S)42 was used to measure the level of bullying by peers on campus among secondary school students. The scale consists of three dimensions: verbal bullying (4 items), physical bullying (4 items), and social relationship bullying (4 items), using a 5-point Likert scale (0=never, 1=once or twice a month, 2=once a week, 3=multiple times a week, 4=almost every day), with a total score ranging from 0 to 48 and higher scores indicating higher levels of bullying victimization.

Anxiety Disorders (AD)

Anxiety disorders were measured using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale43 (GAD-7) developed by Spizer et al. The scale has 7 items, including 7 aspects of tension and anxiety, uncontrollable worry, excessive worry, inability to relax, inability to sit still, irritability, anger, and fear. It is scored on a 5-point scale from not at all to nearly every day, with a higher score indicating more anxiety.

Suicidal Ideation (SI)

Suicide ideation (SI) is a factor motivation for suicidal behavior experienced incidentally by individuals, manifested as ruminations or intentions to suicide, but without outward actions to take or achieve it.44 In this study, the Positive and Negative Suicidal Ideation Scale (PANSI) developed by Osman et al45 was used, with PANSI emphasizing the suicidal ideation of the participants within the last 2 weeks. The scale consists of 2 dimensions and 14 questions, including positive suicidal ideation (6 questions) and negative suicidal ideation (8 questions), rated on a 5-point scale (0=never, 4=always). Positive question options were scored in reverse, and negative questions were scored positively. The total score range was between 0 and 56. Higher scores were associated with higher levels of suicidal ideation.

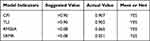

The reliability and validity of the teacher prejudice, teacher preference, peer bullying victimization, anxiety disorder, and adolescent suicidal ideation scales are shown in Table 1. The standardized estimated coefficients of the questions of all scales were greater than 0.6, the significance was less than 0.001, the combined reliability of the scales was greater than 0.36, the convergent validity was greater than 0.5, and the internal consistency was also greater than 0.7, indicating that all scales showed good reliability and validity.

|

Table 1 Reliability and Validity of the Scales |

Data Analysis

Analyses were conducted using SPSS 22.0 and Mplus 8.3, and a two-sided p below 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The descriptive statistics of the Socio-demographic characteristics (mean, standard deviation, number/percentage) were calculated. Pearson correlation was used to analyze the correlations between the dependent, independent, and mediating variables. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used to assess the scale’s internal consistency. SEM analysis with full information likelihood estimation was used to test the hypothesized mediation models. Testing for the direct, indirect, and total effects was based on 1000 bootstrapped samples; effect estimates and bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals (CI) were derived. Indices of good model fit included root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.08 and comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) >0.90.46

Results

Descriptive Data

Table 2 shows the demographic characteristics of the respondents. Of the 21,017 students, the percentage of males (47.71%) and females (52.29%) were similar; the ages were 12 and 15 years old, with the majority of adolescents aged 12 years old, 6516 (31.00%); 58.96% of the adolescents lived in the city, and their monthly cost of living was between 100 and 500, accounting for approximately 71.30% of the total number of students. The mean teacher preference score was 37.918 (SD=10.243), the mean teacher prejudice score was 31.083 (SD=11.208).Among them, “I am embarrassed by teachers spouting things I have said or done in front of others”. “Teachers often punish me more than I deserve”. “Teachers often tell me they do not like my performance at school”. Scored higher, respectively 3.917 (SD=1.414), 3.752 (SD=1.431), and 3.445 (SD=1.358). And the mean peer bullying victimization score was 15.542 (SD=8.191), with verbal bullying 5.443 (SD=3.058), physical bullying 5.443 (SD=4.926), and social relationship bullying 5.174 (SD=2.847), anxiety disorder mean score of 14.251 (SD=7.504), and suicidal ideation mean score of 26.003 (SD=9.035).

|

Table 2 Descriptive Statistics Variables of the Sample (n=21,017) |

Correlation Analysis

Table 3 shows that teacher preference was significantly and negatively correlated with teacher prejudice, peer bullying victimization, generalized anxiety disorder, and adolescent suicidal ideation, with correlations ranging from 0.204 to 0.377. Teacher prejudice, peer bullying victimization, generalized anxiety disorder, and adolescent suicidal ideation were positively correlated with each other, with correlations ranging from 0.242 to 0.527.

|

Table 3 Correlation Analysis Results |

Structural Equation Model Analysis

Mplus 8.3 software was used to construct the structural equation model, and the results showed that the model fit was good: CFI=0.907, TLI=0.902, RMSEA =0.065, and SRMR =0.051 (Table 4).

|

Table 4 Model Fit Indexes |

The results showed that the direct effect of teacher preference on adolescent suicidal ideation was found to be −0.084 (95% CI = −0.096 to −0.071), the total indirect effect was −0.065 (95% CI = −0.073 to −0.059), and the total effect was −0.149 (95% CI = −0.146 to −0.134), all P <0.001, indicating a significant partial mediating effect. The mediation model also found that peer bullying victimization and anxiety disorders had a direct and chain mediating effect between teacher prejudice and adolescent suicidal ideation. In addition, the direct effect of teacher prejudice on adolescent suicidal ideation was 0.075 (95% CI = 0.067 to 0.083), the total indirect effect was 0.065 (95% CI = 0.058 to 0.071), and the total effect was 0.140 (95% CI = 0.130 to 0.149), all P <0.001, indicating a significant partial mediating effect. The mediation model also found a direct and chain mediating effect of peer bullying victimization and anxiety disorders between teacher prejudice and adolescent suicidal ideation (Table 5).

|

Table 5 Intermediation Effects Test |

Figure 2 shows the pathways of teacher discrimination behavior on adolescent suicidal ideation. The results showed that teacher preference had a significant positive effect on adolescent suicidal ideation with a standardized coefficient of −0.229 (P < 0.001), and teacher prejudice had a significant negative effect on adolescent suicidal ideation with a standardized coefficient of −0.216 (P < 0.001), thus, hypothesis 1 (H1-1 and H1-2) was supported. It was found that teacher preference and teacher prejudice both had significant effects on peer bullying victimization (β1 = −0.134, β2 = 0.196, P < 0.001) and that peer bullying victimization had a direct effect on suicidal ideation (β= 0.446, P < 0.001). Thus, hypothesis 2 (H2-1 and H2-2) was supported. Hypothesis 3 (H3-1 and H3-2) was supported by the fact that teacher preference and teacher prejudice both had significant effects on adolescent anxiety disorders (β1 = −0.212, β2 = 0.151, P < 0.001) and that adolescents’ anxiety disorders could directly influence suicidal ideation with a standardized coefficient of 0.474 (P < 0.001). In addition, teacher preference and teacher prejudice can further influence anxiety disorders by influencing adolescent peer bullying victimization, thus reducing or generating suicidal ideation, and adolescent peer bullying victimization as having a direct positive effect on anxiety disorders (β = 0.290, P < 0.001), thus, hypothesis 4 (H4-1 and H4-2) has been fully confirmed.

Discussion

This study used structural equation modeling to examine the effects of teacher discrimination behavior on adolescent suicidal ideation and found that teacher preference had a significant negative effect on suicidal ideation and teacher prejudice had a significant positive effect on suicidal ideation. The mediating effect results indicated significant independent and chain mediating effects of peer bullying victimization, anxiety disorder between teacher discrimination behavior, and adolescent suicidal ideation.

Teacher Discrimination Behavior Has a Significant Impact on Adolescent Suicidal Ideation

School environment factors are important social factors for risk behaviors. Among the various types of school environment factors, teacher-student relationships are gradually gaining attention. Our study focuses on the relationship between teacher discrimination behavior and adolescent suicidal ideation and the pathways through which teacher discrimination behavior influences adolescent suicidal ideation. The results of our study showed that the higher the level of teacher preference, the lower the suicidal ideation of adolescents, and the higher the level of teacher prejudice, the more likely adolescents are to develop suicidal ideation. This is consistent with the findings of Shain (2018),47 Hirsch (2012).48 Teacher preference leads to a sense of acquisition, achievement, and respect, which enhances adolescents’ subjective well-being.49 Even if adolescents develop suicidal ideation due to family relationships and negative events, teacher communication can provide potential channels for emotional venting and stress relief, reducing their feelings of despair. Second, teachers’ preference can also directly weaken the causal factors of adolescents’ suicidal ideation, ie, feelings of loneliness, discrimination, and isolation from social relationships.50 On the contrary, teacher prejudice is a risk factor contributing to adolescent suicidal behavior. Hopelessness theory suggests that when an individual’s desire to be needed and seen conflicts with reality, it leads to an emotional state of self-loathing, which in turn leads to suicidal ideation.51 Acceptance-rejection theory suggests that adolescents’ suicidal behavior is directly related to emotional disapproval,52 and teacher prejudice as a negative way of treatment tends to cut off the emotional relationship between teachers and students, resulting in adolescents’ emotional demands not being met, and adolescents develop negative classroom experiences and a poor sense of belonging, and are more likely to develop suicidal ideation. Therefore, high school teachers should improve their quality, love their jobs and teach at the same time pay more attention to students’ emotional demands, respect students, trust students, understand students, give students care in life, be good at finding students’ points, treat every student fairly, and eliminate the occurrence of differential behavior, so as to reduce students’ suicidal ideation.

Eliminating School Bullying is an Effective Way to Reduce Adolescent Suicidal Ideation

The findings show that peer bullying victimization is an essential factor influencing adolescent suicide, which supports hypothesis 2 of this study. Interpersonal risk theory suggests that negative interpersonal relationships are a fundamental factor in triggering psychological problems such as anxiety and depression in individuals and that poor peer relationships can cause various emotional disorders. According to the escape theory of suicide, it was found that the main reason for individuals to have suicidal ideation is the desire to escape the negative environment.53 Adolescents who suffer from peer bullying victimization will inevitably become traumatized and then choose suicide to escape from their predicament. It has also been found that adolescents who suffer from peer bullying victimization tend to remain silent or are too threatened to seek help from parents or teachers. In the long run, negative emotions such as fear, dread, and anxiety continue to build up, making them more likely to develop suicidal ideation.54 Therefore, it is necessary to prevent suicidal tendencies among teenagers by putting an end to school bullying, cultivating their views on life and values, and raising their legal awareness. Relevant authorities should work together with schools to refine the relevant regulations and deal with abusers in strict accordance with the law and school rules and regulations. Provide victims with ways to seek help, such as family, school, and social institutions. Moreover, strengthen their social support to alleviate the psychological trauma and thus reduce suicidal behavior.

Appropriate Psychological Counseling Can Reduce Adolescent Suicidal Ideation

Studies have found that anxiety disorders are an important cause of suicidal ideation in adolescents. This is consistent with the findings of O’Connor (2021).55 The diathesis-stress model proposes that the generation and development of psychological problems such as anxiety, depression, self-injury, and suicide are consequences of the combined dominant effects of external negative environmental stress and internal psychological sensitivity.56 Also, the integrative theory of motivation and volition suggests that individuals’ negative emotions, such as anxiety, depression, and feelings of loneliness, are the underlying causes of suicidal ideation.31 Adolescents need to cope with various social relationships, including family relationships, teacher-student relationships, and peer relationships, thus, facing tremendous stress, reflected in academic performance and moral codes. As society progresses, the trend of “Survival of the fittest” becomes apparent, and the increasing pressure on adolescents inevitably leads to anxiety, so how to channel the negative emotions of adolescents such as anxiety becomes the key. However, this can be done through family-school coordination. Parents should care more for their children and understand their children’s development and emotional needs. Teachers should also take the initiative to care for students’ needs while strengthening their psychological resilience and focusing on their mental health education. Then, peer support can be developed to strengthen the emotional communication between classmates, reduce the probability of peer bullying, and avoid youth suicide.

Chain Mediating Effect of Peer Bullying Victimization and Anxiety Disorders

The empirical study found that peer bullying victimization and anxiety disorders play an important independent mediating role and chain mediating role between teacher discrimination behavior and adolescent suicidal ideation. First, teacher discrimination behavior is directive in that teachers’ discrimination, prejudice, and isolation of students can also send negative messages to classmates that some students deserve isolation and exclusion.28 Teacher discrimination behavior inevitably triggers peer bullying victimization or causes the aggrieved student to develop anxiety and, thus, suicidal ideation. To some extent, the mechanisms by which teacher discrimination behavior influences adolescent suicidal ideation were explained. At the same time, studies have also found a mediating effect of anxiety disorders in peer bullying victimization and adolescent suicidal ideation. The general strain theory suggests that adolescents experience strain and stress when bullied, which inevitably leads to anxiety disorders, depression, and, thus, directed suicidality.57 The interpersonal theory of suicide also suggests that the necessary elements for individuals to develop suicidal ideation include two components: a frustrated sense of belonging and a perceived sense of exhaustion,58 and teacher prejudice and peer bullying victimization can make adolescents lack a sense of trust and belonging in their surroundings, which, over time, can easily lead to anxiety disorders and thus suicidal ideation in individuals. At the same time, the repeated nature of teacher prejudice, peer bullying victimization, and the victim’s lack of self-protection can lead to desperate situations and suicidal behaviors. Therefore, intervening with peer bullying victimization and adolescent anxiety is a meaningful way to prevent them from developing suicidal ideation. Educators should develop targeted prevention and intervention measures based on the actual situation of school bullying, starting with themselves, setting up a role model image, strengthening the control of adverse events, improving the psychological quality of adolescents, and creating a good school climate.

Limitations

Some limitations to this study warrant consideration. First, teacher discrimination behavior, peer bullying victimization, anxiety disorder, and suicidal ideation are cross-sectional in the study and can be further validated using longitudinal data in the future. Second, since the information was gathered from the participants in the study, self-report/recall bias may have existed. However, it is difficult to achieve continuous adolescent participation in cohort studies, and sample size should be addressed.

Conclusions

Suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior, as the most severe psychological problems and means of adolescents, bring significant harm to an individual social function and trigger significant economic and social pressure, which is detrimental to social development and social stability. Therefore, more attention should be paid to adolescents’ suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior. In this study, a structural equation model was used to examine the effect of teacher discrimination behavior on adolescent suicidal ideation. It was found that teacher preference had a significant negative effect on suicidal ideation and teacher prejudice had a significant positive effect on suicidal ideation. The mediating effect found a significant independent and chain mediating effect of peer bullying victimization and anxiety disorder between teacher discrimination behavior and adolescent suicidal ideation.

Data Sharing Statement

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kangda College of Nanjing Medical University (2022-01) and all participants signed informed consent.

Acknowledgments

Mao-min Jiang, Ji-neng Chen, Xin-cheng Huang are co-first authors for this study. The authors thank all the participants, assistants, and researchers for their contribution to this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant numbers 72274023), Social Science Project of the Ministry of Education of China (Grant Numbers 22YJA890037). The sponsors of the project had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and writing the manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Becker M, Correll CU. Suicidality in childhood and adolescence. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2020;04:1–10. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2020.0261

2. Emelianchik-Key K. Non-suicidal self-injury in childhood. Non Suicidal Self Inju Throug Life. 2019;10:1–22. doi:10.4324/9781351203593-2

3. Salk RH, Hyde JS, Abramson LY. Gender differences in depression in representative national samples: meta-analyses of diagnoses and symptoms. Psychol Bull. 2017;143(8):783–822. doi:10.1037/bul0000102

4. Brent DA, Melhem NM, Oquendo M, et al. Familial pathways to early-onset suicide attempt. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(2):160. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2141

5. Breslin K, Balaban J, Shubkin CD. Adolescent suicide: what can pediatricians do? Curr Opin Pediatr. 2020;32(4):595–600. doi:10.1097/mop.0000000000000916

6. World Health Organization. Mental health—Suicide Prevention. World Health Organization; 2014.

7. Shobhana SS, Raviraj KG. Global trends of suicidal thought, suicidal ideation, and self-harm during COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Egypt J for Sci. 2022;12(1). doi:10.1186/s41935-022-00286-2

8. Mo L, Li H, Zhu T. Exploring the suicide mechanism path of high-suicide-risk adolescents—based on weibo text analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(18):11495. doi:10.3390/ijerph191811495

9. Zhu X, Tian L, Huebner ES. Trajectories of suicidal ideation from middle childhood to early adolescence: risk and protective factors. J Youth Adolesc. 2019;48(9):1818–1834. doi:10.1007/s10964-019-01087-y

10. Mann JJ, Waternaux C, Haas GL, et al. Toward a clinical model of suicidal behavior in psychiatric patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(2):181–189. doi:10.1176/ajp.156.2.181

11. Sun P, Sun Y, Fang D, et al. Cumulative ecological risk and problem behaviors among adolescents in secondary vocational schools: the mediating roles of core self-evaluation and basic psychological need satisfaction. Front Public Health. 2021;9:1–8. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.591614

12. Nock MK, Green JG, Hwang I, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(3):300. doi:10.1001/2013.jamapsychiatry.55

13. Chen X, Li M, Gong H, et al. Factors influencing adolescent anxiety: the roles of mothers, teachers and peers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(24):13234. doi:10.3390/ijerph182413234

14. Liu F, Gai X, Xu L, et al. School engagement and context: a multilevel analysis of adolescents in 31 provincial-level regions in China. Front Psychol. 2021;12:1–12. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.724819

15. Symonds J, Hargreaves L. Emotional and motivational engagement at school transition. J Early Adolesc. 2014;36(1):54–85. doi:10.1177/0272431614556348

16. Rayan A, Harb AM, Baqeas MH, et al. The relationship of family and school environments with depression, anxiety, and stress among Jordanian students: a cross-sectional study. SAGE Open Nurs. 2022;8:237796082211384. doi:10.1177/23779608221138432

17. Zhang T, Wang Z, Liu G, et al. Teachers’ caring behavior and problem behaviors in adolescents: the mediating roles of cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression. Pers Individ Dif. 2019;142:270–275. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2018.10.005

18. Gale A. Examining black adolescents’ perceptions of in-school racial discrimination: the role of teacher support on academic outcomes. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;116:105173. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105173

19. Zhu M, Urhahne D, Rubie-Davies CM. The longitudinal effects of teacher judgement and different teacher treatment on students’ academic outcomes. Educ Psychol. 2017;38(5):648–668. doi:10.1080/01443410.2017.1412399

20. Kyere E, Karikari I, Teegen BC. The associations among teacher discrimination, parents’ and peer emotional supports, and African American Youth’s School bonding. Fam Soc. 2020;101(4):469–483. doi:10.1177/1044389419892277

21. Betts LR, Houston JE, Steer OL. Development of the multidimensional peer victimization scale–revised (MPVS-R) and the multidimensional peer bullying scale (MPVS-RB). J Genet Psychol. 2015;176(2):93–109. doi:10.1080/00221325.2015.1007915

22. Sui XH, Chen W. Analysis of the current situation and related risk factors of suicide among middle school students. Chin J Health. 2011;32(9):1146–1148. doi:10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2011.09.062

23. Schmidt M, Bagwell C. Peer victimization and bullying in childhood and adolescence. Psychology. 2020;5:1–12. doi:10.1093/obo/9780199828340-0263

24. Crepeau-Hobson F, Leech NL. Peer victimization and suicidal behaviors among high school youth. J Sch Violence. 2015;15(3):302–321. doi:10.1080/15388220.2014.996717

25. Holt MK, Kaufman Kantor G, Finkelhor D. Parent/child concordance about bullying involvement and family characteristics related to bullying and peer victimization. J Sch Violence. 2008;8(1):42–63. doi:10.1080/15388220802067813

26. Corcoran L, Mc Guckin C. Addressing bullying problems in Irish schools and in Cyberspace: a challenge for school management. Educ Res. 2014;56(1):48–64. doi:10.1080/00131881.2013.874150

27. Rudasill KM, Snyder KE, Levinson H, et al. Systems view of school climate: a theoretical framework for research. Educ Psychol Rev. 2017;30(1):35–60. doi:10.1007/s10648-017-9401-y

28. Cui S, Cheng Y, Xu Z, et al. Peer relationships and suicide ideation and attempts among Chinese adolescents. Child Care Health Dev. 2010;37(5):692–702. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01181.x

29. Vergara GA, Stewart JG, Cosby EA, et al. Non-suicidal self-injury and suicide in depressed adolescents: impact of peer victimization and bullying. J Affect Disord. 2019;245:744–749. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.084

30. O’Connor RC, Platt S, Gordon J. International Handbook of Suicide Prevention Research, Policy and Practice. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 2011.

31. Liu D, Liu S, Deng H, et al. Depression and suicide attempts in Chinese adolescents with mood disorders: the mediating role of Rumination. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2022;6:1–10. doi:10.1007/s00406-022-01444-2

32. Jin J. Screening for depression and suicide risk in children and adolescents. JAMA. 2022;328(15):1570. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.18187

33. Rottenberg J. The Depths: The Evolutionary Origins of the Depression Epidemic. New York: Basic Books, A Member of the Perseus Books Group; 2014.

34. Starrs B. Anxiety, depression, self-harm and suicide. Adolesc Psychother. 2018;86–102. doi:10.4324/9780429460746-7

35. Lönnqvist J. Mood and anxiety disorders in suicide and suicide attempters. In: Oxford Textbook of Suicidology and Suicide Preventio. Oxford Acadmic; 2021:261–268. doi:10.1093/med/9780198834441.003.0031

36. Şahin N, Kırlı U. The relationship between peer bullying and anxiety-depression levels in children with obesity. Anadolu J Psikiyatri. 2020;1:1–12. doi:10.5455/apd.133514

37. Peng C, Wang Z, Yu Y, et al. Co-occurrence of sibling and peer bullying victimization and depression and anxiety among Chinese adolescents: the role of sexual orientation. Child Abuse Negl. 2022;131:105684. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105684

38. Jennifer WY. How do we target NSSI in BPD? Exploring the relationship between emotion dysregulation, interpersonal dysfunction, and non-suicidal self-injury; 2021:1–12.

39. Brophy JE, Good TL. Teachers’ communication of differential expectations for children’s classroom performance: some behavioral data. J Educ Psychol. 1970;61(5):365–374. doi:10.1037/h0029908

40. Weinstein RS, Marshall HH, Sharp L, et al. Pygmalion and the student: age and classroom differences in children’s awareness of teacher expectations. Child Dev. 1987;58(4):1079. doi:10.2307/1130548

41. Babad E. Teachers’ differential behavior. Educ Psychol Rev. 1993;5(4):347–376. doi:10.1007/bf01320223

42. Xie JS, Lu YX, George GB, et al. Research on the reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Delaware Bullying Victimization Scale (Student Volume). Chin J Clinical Psychol. 2015;23(4):594–596. doi:10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2015.04.006

43. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

44. Chae W, Park EC, Jang SI. Suicidal ideation from parents to their children: an association between Parent’s suicidal ideation and their children’s suicidal ideation in South Korea. Compr Psychiatry. 2020;101:152181. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2020.152181

45. Osman A, Gutierrez PM, Jiandani J, et al. A preliminary validation of the positive and Negative Suicide Ideation (pansi) inventory with normal adolescent samples. J Clin Psychol. 2003;59(4):493–512. doi:10.1002/jclp.10154

46. Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol Bull. 1990;107(2):238–246. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238

47. Kong L, Sareen J, Katz LY. School-based suicide prevention programs. Int Handbook Suicide Prev. 2016;725–742. doi:10.1002/9781118903223.ch41

48. Hirsch JK, Visser PL, Chang EC. Teacher behaviors and suicide risk in a college sample. Arch Suicide Res. 2012;16(2):111–123. doi:10.1080/13811118.2012.668165

49. Jiang MM, Gao K, Wu ZY, et al. The influence of academic pressure on adolescents’ problem behavior: chain mediating effects of self-control, parent–child conflict, and subjective well-being. Front Psychol. 2022;13:1–10. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.954330

50. Ross V, Kõlves K, De Leo D. Teachers’ perspectives on preventing suicide in children and adolescents in schools: a qualitative study. Arch Suicide Res. 2016;21(3):519–530. doi:10.1080/13811118.2016.1227005

51. Elledge D, Zullo L, Kennard B, et al. Refinement of the role of hopelessness in the interpersonal theory of suicide: an exploration in an inpatient adolescent sample. Arch Suicide Res. 2019;25(1):141–155. doi:10.1080/13811118.2019.1661896

52. Rohner RP, Khaleque A. Testing central postulates of parental acceptance-rejection theory (PARTheory): a meta-analysis of cross-cultural studies. J Fam Theory Rev. 2010;2(1):73–87. doi:10.1111/j.1756-2589.2010.00040.x

53. Landrault H, Jaafari N, Amine M, et al. Suicidal ideation in elite schools: a test of the interpersonal theory and the escape theory of suicide. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2019;50(1):201–210. doi:10.1111/sltb.12578

54. DuPont-Reyes MJ, Villatoro AP, Phelan JC, et al. School Mental Health curriculum effects on peer violence victimization and perpetration: a cluster‐randomized trial. Journal of School Health. 2020;91(1):59–69. doi:10.1111/josh.12978

55. O’Connor RC, Pirkis J, Cox GR. The international COVID-19 suicide prevention research collaboration: protocol for a coordinated series of meta-analyses to identify correlates of risk and prevention of suicidal behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Open. 2021;11(3):e048736. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048736

56. Cleare S, Wetherall K, Eschle S, et al. Using the integrated motivational-volitional (IMV) model of suicidal behaviour to differentiate those with and without suicidal intent in hospital treated self-harm. Prev Med. 2021;152:106592. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106592

57. Agnew R, White HR. An empirical test of general strain theory. Criminology. 1992;30(4):475–500. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.1992.tb01113.x

58. Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Gordon KH, et al. Suicidal desire and the capability for suicide: tests of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior among adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76(1):72–83. doi:10.1037/0022-006x.76.1.72

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.