Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

The Effect of Growth Mindset on Adolescents’ Meaning in Life: The Roles of Self-Efficacy and Gratitude

Authors Zhao H , Zhang M, Li Y, Wang Z

Received 24 July 2023

Accepted for publication 18 October 2023

Published 13 November 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 4647—4664

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S428397

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Mei-Chun Cheung

Hui Zhao, Ming Zhang, Yifei Li, Zhenzhen Wang

Faculty of Education, Henan Normal University, Xinxiang, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Ming Zhang; Hui Zhao, Faculty of Education, Henan Normal University, Jianshe Road, Muye District, Xinxiang, Henan Province, People’s Republic of China, Email [email protected]; [email protected]

Background: Prior research has demonstrated that individuals’ growth mindset can predict their happiness and psychological health. As a vital gauge of psychological health, meaning in life may be connected to a growth mindset.

Methods: This study employs a positive psychological perspective and uses Chinese adolescents as the study population. We manipulated the level of growth mindset (high growth mindset vs low growth mindset) in two experiments to examine the effects of growth mindset on adolescents’ meaning in life. Additionally, we examined the roles of self-efficacy as a mediator (Study 1) and gratitude as a moderator (Study 2).

Results: Study 1 revealed positive correlations among growth mindset, self-efficacy, and meaning in life. Teenagers with a high growth mindset perceived and experienced life meaning more strongly than those with a low growth mindset. Growth mindset significantly predicted meaning in life, and self-efficacy fully mediated the connection between growth mindset and meaning in life. In Study 2, the connection between growth mindset and meaning in life was moderated by gratitude: in the high-gratitude condition, teens’ growth mindsets had a direct significant influence on meaning in life. In contrast, in the low-gratitude situation, growth mindset did not significantly affect meaning in life. Moreover, the fully mediating role of self-efficacy was verified.

Conclusion: The results reveal the mechanism of action by which adolescents’ growth mindset affects their meaning in life, broadening the research related to adolescents’ growth mindset and providing important theoretical inspiration and practical guidance for teachers, parents and counselling workers to help adolescents obtain higher meaning in life.

Keywords: growth mindset, meaning in life, self-efficacy, gratitude, adolescent

Introduction

Aristotle claimed that the essence of human education lies in the cultivation of the mind, and for individuals, a cultivated mind is a goal for which every natural person should strive.1 The mind, the so-called way of thinking, influences the direction of individuals’ lives, and the direction of life reflects the significance and worth of life. Adolescence is a sensitive period for teenagers to feel meaning in life, and some teenagers have a tendency to be bored and to feel empty and worthless.2 They have low perceptions and experiences of meaning in life, lack autonomous motivation to learn, and think that life has no motivation.3 At present, the phenomena of “hollow disease” and “lying flat” are common among Chinese students. Their basic characteristics are weak belief consciousness, a lack of self-cognition, and feeling that learning is worthless; these phenomena are caused by a lack of meaning and a crisis of spiritual value.4 However, in real life, everyone has their own goals, and they will pursue and achieve them through their own efforts, when they fail in this search, they experience a strong sense of loss and emptiness, which affects their emotional health and daily work and study.5 Individuals’ meaning in life depends on their subjective experiences and feelings.6 As an important indicator of individual mental health, a sense of meaning in life is important and valuable for the healthy development of the individual’s body and mind.7 It depends on individuals’ perceptions, understanding and pursuit of their life aims and principles, and individuals obtain a sense of achievement and satisfaction after realizing their goals and values. At present, numerous scholars are beginning to pay more attention to how positive psychology affects meaning in life.8 Hence, this research holds that the cultivation of meaning in life can also be explored from a positive cognitive perspective. Is a growth mindset conducive to enhancing individuals’ perceptions of and appreciation for life meaning? Self-determination theory posits that these individuals more easily arouse their inner motivations and hope, leading them to believe that they have some control over their success, so they are more likely to perceive life as having meaning and value.9 Individuals with a growth mindset fit this profile.10 To answer the above question, this study attempts to introduce individuals’ growth mindsets as an upstream predictor to explore its link with meaning in life.

Is there a psychological mechanism by which growth mindset affects perception of life meaning? In the realm of teenage education, most academics focus on how a growth mindset affects students’ academic efficacy.11 Therefore, a growth mindset and general efficacy may be closely associated. When individuals have higher perceptions and evaluations of their own ability, they are more inclined to approach life positively, thus improving their perceptions of the realization of life goals and value.12 Therefore, it is plausible to suggest that self-efficacy could serve as a significant mediating variable in the association between a growth mindset and the experience of finding purpose and significance in life. In addition, previous studies on meaning in life have discovered that there are consistent disparities in how each person perceives meaning in life.13 These differences may be due to individual psychological qualities and emotions. In view of this, scholars have explored whether positive psychological qualities such as optimism are important moderating variables that affect life meaning.14 Furthermore, the broaden-and-build theory posits that gratitude has the capacity to expand positive awareness and cognitive processes, leading to the activation of corresponding behaviors; thus, it is an important protection resource in the process of individual growth. Each person’s comprehension of life’s purpose may vary with their level of individual gratitude.15 Therefore, it is also interesting to investigate whether the impact of growth mindset on the sense of meaning in life is affected by the level of individual gratitude.

Based on the above discussion, the present research investigates the potential positive influence of adolescents’ growth mindset on the on the development of life meaning. Its contribution is threefold. First, Study 1 used an experimental research methodology to explore the link between growth mindset and the sense of meaning in life and self-efficacy by manipulating the growth mindset of individuals. The findings reveal a causal connection between a person’s growth mindset and their comprehension and perception of the meaning of life as well as the underlying mechanisms. Second, in Study 2, the researchers employed an experimental methodology to further investigate the phenomenon. The findings of the current investigation offer further evidence of the mediating role of self-efficacy. In addition, the researchers found that individual gratitude played a key moderating role. Third, the study focused on Chinese adolescents as the primary participants, offering a valuable point of reference for future research conducted in different cultural contexts. In conclusion, this study explores the underlying mechanisms of how adolescent growth mindset affects meaning in life from a positive psychology perspective, which can promote the psychological health of adolescents in a positive way.

Literature Review

Growth Mindset and Meaning in Life

Recently, researchers and practitioners in the disciplines of education, management, and organization have favoured the growth mindset due to its unique influence and value. Its conception can be traced back to the implicit theory of intelligence, on which Dweck relied in proposing the two thinking modes regarding intelligence: growth mindset versus fixed mindset.16 The growth mindset refers to individuals being able to accurately evaluate themselves, believing that their intelligence, as well as other abilities, can be improved by effort, being willing to accept challenging tasks, and continuing to grow through their failure experiences.17 Conversely, individuals with fixed mindsets tend to embrace nativism, think that their efforts and abilities are difficult to change, think that effort is of little significance and be unwilling to step out of their comfort zones.18 At present, many scholars claim that this theory is single-dimensional; that is, the way of thinking can change within a cognitive continuum,19,20 so a fixed mindset is also called a low-growth mindset.21 Research on growth mindset has produced many results in the field of learning and work, such as being beneficial to middle school students’ learning engagement and academic literacy,22,23 improving individual job satisfaction and achieving career success.24,25 However, some scholars have argued that growth mindset can also help individuals develop healthy lifestyles, decrease bad living habits, predict individual mental health problems and increase happiness.26,27 Consequently, the relationships between growth mindset and other factors in the realm of psychological health continue to merit consideration and discussion. Meaning in life depends on individuals’ perceptions, understanding and realization of their life goals and meanings.28 In general, there are two aspects: having and seeking meaning. As a way of thinking positively, a growth mindset may also be linked to meaning in life. Prior research has found that people with growth mindsets may be far more likely to succeed in their academic and professional endeavours, experience higher happiness and satisfaction, and think that their existence is valuable and meaningful.29 In addition, Wong scholars have proposed the meaning management theory, which states that individuals can find the source of happiness and hope in life by managing their inner worlds and positive beliefs to obtain a sense of meaning and satisfaction.30 People with a growth mindset find more meaning in life. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis.

H1: Growth mindset is positively correlated with meaning in life.

Mediating Effect of Self-Efficacy

The concept of self-efficacy was introduced by Bandura31 in reference to individuals’ belief perceptions of the abilities they need to achieve a given goal. An individual with efficacy believes that he or she is competent for an activity or task. According to self-determination theory, every person is an active organism with a basic, internal tendency to learn, improve, and grow, and this trend is beneficial for the growth of personal abilities.32 Individuals with a growth mindset coincide with this feature. They see the ability to alter their actions and attributes as a result of exerting effort, and such individuals achieve their goals in a proactive way, making initiative a prerequisite for the generation of efficacy. Zhang’s findings indicated that entrepreneurs who possess a growth mindset tend to have optimistic psychological expectations of the future of their entrepreneurial endeavours. Additionally, these individuals demonstrate a heightened ability to adapt and overcome challenges and failures commonly seen in the entrepreneurial domain,33 thus improving their entrepreneurial efficacy. Several studies have discovered a link between a growth mindset and academic self-efficacy. When a combined intervention of mindfulness and the growth mental model is embedded in curriculum, it can boost math self-efficacy and lessen math anxiety.34 Entrepreneurial efficacy and academic efficacy, as the extension and expansion of general efficacy, can serve as a reflection of the association between growth mindset and self-recognition of competence. The implication is that the presence of a growth mindset is a strong predictor of an individual’s level of self-efficacy.

At present, an increasing number of researchers pay attention to not only the antecedent variables of self-efficacy but also its positive effects. According to the cognitive view of self-schema theory, self-schema is a basic cognitive structure and belief that can have a certain impact on individuals’ self-related information.35 Generally, self-schema includes positive and negative types. A positive self-schema can effectively promote individuals to produce positive behaviours and promote mental health. Self-efficacy, to some extent, can also be understood as a positive self-schema that is crucial to the growth and development of individuals. According to studies, individuals who have a high level of recognition of their abilities tend to deal with pressure in learning and life positively. When they feel the joy of success, they tend to improve their self-confidence and have higher degrees of satisfaction and subjective well-being in school and life.36,37 In addition, when individuals obtain positive psychological resources such as life satisfaction, it can help them think positively and pursue their life goals and then realize meaning and value in their lives.38 Therefore, it is inferred that individual self-efficacy significantly predicts meaning in life. On this basis, this study proposes the following hypothesis.

H2: Self-efficacy mediates the link between a growth mindset and meaning in life.

Moderating Effect of Gratitude

As positive psychology has grown rapidly, gratitude has gradually become one of the focuses of scholars at home and abroad. Gratitude, as a psychological emotion, is the inner recognition of the help individuals give themselves and that given by others and nature and produces a kind of gratitude that leads them to try to return positive feelings.39,40 Fredrickson’s expand and build theory of emotions posits that good feelings and emotions increase personal attention and cognition.41 This is conducive to them responding to adversity and constructing resources and then promotes the realization of goals and the acquisition of experience. From a theoretical perspective, gratitude, as a protective factor in the process of individual development, can promote individual positive subjective experiences and alleviate negative effects.42 Specifically, compared with individuals with low levels of gratitude, individuals who are often grateful flexibly recognize various things and often respond to challenges with a positive attitude. In addition, students with a high level of gratitude may have clearer goals for themselves, have stronger intrinsic motivation to achieve their purposes and values and are more inclined to realize meaning and value in their lives after achieving their goals.43 Therefore, when individuals have positive emotions of high gratitude, their cognitive thinking patterns also improve. On this basis, individuals who repeatedly experience the positive emotion of gratitude and maintain a flexible cognitive level may also increase their subjective experiences of life purpose and value; that is, individuals with high growth mindsets and high gratitude may experience more meaning in life. At present, even in the absence of direct evidence of the moderating effect of gratitude on the relationship between the two, some scholars have conducted preliminary explorations. Some scholars found that individuals’ gratitude levels can regulate the mediating relationship between cognitive thinking and subjective feelings;44 that is, gratitude has a regulating effect on the mediating process between rumination and suicidal ideation. However, foreign scholars have conducted empirical research showing that trait gratitude moderates college students’ cognitive styles related to being unable to tolerate uncertainty and their subjective feelings of intercultural pressure.45 All the above studies provide indirect explanations and evidence for this study. Based on the discussion thus far, the study presents the following hypothesis.

H3: The association of growth mindset and meaning in life is moderated by individual gratitude level; that is, compared with individuals with low gratitude level, for those with higher levels of gratitude, growth mindset has a stronger predictive effect on the possession and pursuit of meaning in life.

In summary, this investigation focuses on Chinese adolescents as the participants and aims to explore the underlying mechanisms by which growth mindset promotes life meaning, drawing on self-determination theory and other relevant theoretical frameworks. Recently, several researchers have demonstrated that the utilization of experimental methodologies has the potential to augment individuals’ experiences with and comprehension of the concept of purpose in life.46–48 Hence, to verify the above three hypotheses, this study will also use experimental methods. Study 1 explores the relationship and psychological mechanism by manipulating mindset (high growth mindset vs low growth mindset) among 106 youth participants. Study 2 first measured the gratitude level of individuals and divided them into high and low groups (high gratitude vs low gratitude) and then manipulated mindset (high growth mindset vs low growth mindset) to further explore whether gratitude regulates the link between growth mindset and meaning in life among 136 youth participants. Therefore, based on the above content, this study’s theoretical framework is as follows (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1 Research hypothesis model. |

Study 1

Purpose

In a laboratory setting, a reading material paradigm was used to activate the subjects’ high and low growth mindsets, and then the causal relationship and psychological mechanism between growth mindset and meaning in life were investigated.

Methods

Participants

A total of 106 teenagers from a junior high school in Xinxiang City in the province of Henan who were enrolled in grades 7, 8, or 9 were chosen at random to take part in this experiment. The participants had an average age of 14.04 years, with 42 boys and 64 girls. Each participant in the study was assigned randomly to one of the two experimental settings (high- and low-growth mindset), with 53 subjects in each condition. The numbers of boys and girls in the upper and lower groups were 21 and 32, respectively. Both students and their parents completed informed consent forms, and this work received approval from the Henan Normal University Ethics Committee.

Design

A single-factor between-subject design was used to test the research hypothesis (mindset: high growth mindset vs low growth mindset).

Procedures and Materials

- Growth mindset manipulation: Learning from the priming method of previous studies, that is, reading scientific materials to initiate a growth psychological orientation, has been proven to be an effective strategy.49,50 After the subjects entered the designated experimental classroom, they were asked to complete a scientific material reading task that manipulated their way of thinking. We directly used reading materials that have been validated by previous scholars, and specific details were as follows: the high-growth mindset condition emphasized that “the talents of the great men Leonardo Da Vinci and Einstein were due to challenging environments, their talent has almost nothing to do with their genetic makeup, these great people are loved because they face challenges and work hard to overcome them”; and the low-growth mindset condition emphasized that “talent comes from DNA, not nurture; the talents of the great Mozart and Einstein were almost inborn, and their talents probably came from their DNA”.51,52

- Growth mindset measurement: After completing the reading task, both groups of subjects rated the level of growth mindset experienced at that time. Two questions from the Growth Mindset Scale developed by Dweck were used.53,54 The following specifics were used for the growth mindset manipulation test: “No matter what my intelligence level, I can always change a lot” and “No matter who I am, I can always change to a large extent”. We used a seven-point Likert scale, and the scores ranged from 1 to 7, with 1 representing “completely disagree” and 7 representing “completely agree”. Previously, scholars have shown whether there is a difference between the high-growth mindset group and the low-growth mindset group by calculating their scores, so we followed this approach.55,56 We obtained the final results for the high-growth mindset and low-growth mindset groups by calculating the average scores of the two questions answered by the subjects in each group. Subsequently, the significance of the difference in growth mindset between the two groups was calculated to confirm the validity of the experimental manipulation. The overall Cronbach coefficient is 0.884.

- Meaning in life scale: The Meaning in Life Scale (MLQ) revised by Wang Xinqiang was adopted;57 it has 10 items, with 9 questions positively scored (such as “My life has a clear direction”) and 1 question reverse scored. We utilized a Likert scale with seven points, and the scores ranged from 1 to 7, with 1 representing “completely disagree” and 7 representing “completely agree”, and one question was reverse scored. The scores of the responses to the 10 questions were computed as an average, with higher scores indicating a heightened perception of life significance. Previous investigations conducted in China have demonstrated the reliability and validity of the scale.58 The Cronbach coefficient in this study is 0.805.

- Self-efficacy scale: The self-efficacy component of the Compound Psychological Capital Scale that was developed by Lorenz was selected for this study, and there were three items in total,59 all of which were positively scored (such as “If I put in effort, I can solve most problems”). We utilized a Likert scale with seven points, and the scores ranged from 1 to 7, with 1 representing “completely disagree” and 7 representing “completely agree”. The average score across the three questions was calculated for the data analysis, with higher scores indicating better self-efficacy. The scale’s reliability and validity have been established by previous studies conducted in China.60 The Cronbach coefficient is 0.758.

- The subjects reported their demographic information, including gender, age, grade and other basic information. After the experiment, we explained our experimental design and purpose to the subjects, making it clear that the reading materials manipulating a low growth mindset were false content. In addition, we communicated the impact of a low growth mindset to the students and helped them shape their growth mindset through reading materials, The content of the material emphasises the need to enhance self-identity and self-confidence through the discovery of one’s own strengths. Finally, they were thanked for their participation and given neutral signature pens and beautiful motivational bookmarks as compensation. Seven days after the end of the experiment, we randomly selected 10 subjects from the low-growth mindset group and asked them the question, “When you learned that the reading material was false content, did you feel that it negatively impacted your efforts to find meaning in your life goals?” The students gave the same answer, “It does not have a negative impact”.

Results

Manipulation Check

To evaluate the efficacy of the growth mindset manipulation, a variance homogeneity test was first conducted on the data, and the result showed that p=0.62, indicating homogeneity of variance. Then, the data were analysed using an independent sample T-test, and the scores of the high-growth mindset group (M=5.85, SD=0.77) were significantly higher than those of the low-growth mindset group (M=3.03, SD=0.89), t(106)=17.39, d=3.15, p<0.001, 95% CI [2.49, 3.14]. The outcomes demonstrate that the growth mindset manipulation was effective.

Correlation Analysis

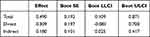

First, groups with a growth mindset were coded, with high groupings coded as 1 and low groupings coded as 0. The findings of a correlation analysis indicated a significant positive link between the growth mindset and meaning in life (r=0.382, p<0.01), which was consistent with theoretical expectations and verified that meaning in life was found to be positively connected with growth mindset, laying a preliminary empirical foundation for the research hypothesis. In addition, growth mindset was positively correlated with self-efficacy (r=0.423, p<0.01), and a positive correlation was found between self-efficacy and meaning in life (r=0.406, p<0.01) (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis |

Hypothesis Testing

First, an independent sample t-test was performed. With meaning in life as an outcome variable, the results are as follows (Figure 2): the level of meaning in life in the high-growth mindset group (M=5.06, SD=0.68) was significantly higher than that in the low-growth mindset group (M=4.36, SD=1.00), t(106)=4.21, d=0.69, p<0.001, 95% CI [0.37, 1.03]. To further test the predictive relationships among variables, gender and age were used as control variables. The regression analysis findings indicated that meaning in life was predicted by growth mindset (F(3, 102)=9.53, R2=0.196, β=0.267, p (0.01)<0.05). Therefore, the positive predictive effect of growth mindset on sense of meaning in life was verified again through behavioural experiments. Hypothesis 1 is validated.

|

Figure 2 Distribution of scores across groups. |

Second, a mediating effect test of self-efficacy was carried out, and the data on self-efficacy and meaning in life were standardized. According to the method proposed by Hayes,61 the Process macro’s Model 4 was employed. For the outcome variable “meaning in life”, a high-growth mindset was coded as 1, and a low-growth mindset was coded as 0. Age and gender (1= female, 0= male) were selected as the main control variables. Table 2 presents the outcomes. In the total effect of Equation 1, growth mindset positively predicts meaning in life (β=0.490, p<0.05). In Equations 2 and 3, growth mindset had no significant direct predictive effect on meaning in life, self-efficacy was predicted by growth mindset (β=0.745, p<0.001), and self-efficacy had a significant predictive effect on meaning in life (β=0.242, p<0.01). In addition, to further clarify the mediating effect size of self-efficacy, a bootstrap test was conducted on self-efficacy. The results are shown in Table 3. The confidence interval 95% CI [-0.081, 0.700] of the direct effect of growth mindset on meaning in life contains 0, while the indirect effect 95% CI [0.025, 0.417] does not contain 0, illustrating that the link between growth mindset and sense of meaning in life is fully mediated by self-efficacy. Hypothesis 2 is validated.

|

Table 2 Test of Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy (N=106) |

|

Table 3 Bootstrap Analysis (N=106) |

In summary, Hypotheses 1 and 2 were verified in Study 1; that is, the causal relationship between growth mindset and meaning in life and the mediating role of self-efficacy were supported by experimental research. There is a positive correlation between growth mindset and sense of meaning in life, but is the relationship between the two affected by other moderating variables? In the second study, a questionnaire survey and behavioural experiment were used for further exploration.

Study 2

Purpose

In a laboratory setting, a reading material paradigm was used to activate the subjects’ high and low growth mindsets and to investigate the mechanisms by which growth mindsets influence meaning in life and whether the relationship is mediated by gratitude.

Methods

Participants

The sample size estimation was conducted using G*Power.62 “F-test - ANOVA: Fixed effects, special, main effects and interactions” was selected, the effect size was f=0.25, α=0.05, and the statistical test power was 1-β=0.80; thus, the necessary sample size was 128 people. In total, 136 subjects from a junior middle school in Henan Province, including 52 males and 84 females, with a mean age of 13.92 years, participated in the second part of the experiment. No subjects had performed similar experiments, and they received appropriate remuneration after the experiment. The parents and students completed the needed consent form. Additionally, the research was authorized by Henan Normal University’s Ethics Committee.

Design

The experimental process consists of two parts. In the first part, the gratitude of students was measured by questionnaire, the top and bottom 30% were used as the standard, and 68 people in the high and low-gratitude groups were selected to enter the manipulated growth mindset experiment. In the second stage, a 2 (growth mindset: high/low) × 2 (gratitude: high/low) factor design was used, with the subjects divided into four groups: 34 people were in the high-growth mindset, low-gratitude group; 34 people were in the high-growth mindset, high-gratitude group; 34 people were in the low-growth mindset, low-gratitude group; and 34 people were in the low-growth, mindset high-gratitude group.

Procedures and Materials

- Gratitude scale: The Adolescent Gratitude Scale compiled by He and other scholars was used for measurement.63 A total of 237 junior high school students were enlisted, and 10 subjects who failed to finish the test or repeated a given answer option more than 5 consecutive times were excluded. There were 227 valid questionnaires from 84 male students and 143 female students, the average age of whom was 13.89 years. The scale contains 23 question items, and we utilized a 7-point Likert scale. The scores ranged from 1 to 7, with 1 representing “completely disagree” and 7 representing “completely agree”. The greater the overall average score was, the higher the individual’s gratitude level. This scale has been shown to be highly reliable and valid in Chinese studies.64 The scale’s Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is 0.824. According to the total average score of gratitude, 30% before and after the ranking were defined as the high group (higher than 6.04) and low group (lower than 5.35), respectively. Subsequently, a total of 68 students were selected for both the high-gratitude and low-gratitude groups in the experimental study. The high-gratitude group consisted of 27 male participants and 41 female participants, with an average age of 13.88±0.96 years. The low-gratitude group had 25 male participants and 43 female participants, with an average age of 13.96±0.91 years. The gratitude scores of the high group and low group were M=6.38 (SD=0.23) and M=4.83 (SD=0.42), respectively. An independent sample t-test found that the high group had significantly higher scores than the low group, t(136)=26.51, d=3.69, p<0.001, 95% CI [1.44, 1.67].

- Growth mindset manipulation: same as in study 1.

- Growth mindset measurement: same as in study 1, and the scale’s Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is 0.791.

- Meaning in life scale: same as in study 1, and the scale’s Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is 0.780.

- Self-efficacy scale: same as in study 1, and the scale’s Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is 0.809.

- Participants provided information about their gender, age, grade, and other basic characteristics. The individuals were informed of the study’s goal after the experiment, and they were told that there was no good or bad level to alleviate any adverse reactions. Finally, the researchers expressed gratitude to the students participating in the experiment and gave them neutral pens, bookmarks and other gifts as compensation.

Results

Manipulation Check

The independent samples t-test was first performed, and the findings demonstrated that the growth mindset scores of the high-growth mindset group (M=5.58, SD=1.12) were significantly higher than those of the low-growth mindset group (M=4.43, SD=1.40), t(136)=5.33, d=0.83, p<0.001, 95% CI [0.73; 1.58]. The subjects’ mindsets were manipulated effectively.

Hypothesis Testing

Firstly, the data was subjected to the test of homogeneity of variance and the results showed that p(0.22)>0.05, indicating homogeneity of variance. A 2 x 2 analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted with Growth Mindset and Gratitude as the independent variable and Sense of Meaning in Life as the dependent variable. The results showed that the main effects of growth mindset [F(1,132)=19.72, p<0.001, η2= 0.13] and gratitude [F(1,132)=106.08, p<0.001, η2=0.45] were both statistically significant; and the interaction between growth mindset and gratitude was significant, F(1,132)=4.43, p<0.05, η2=0.03.

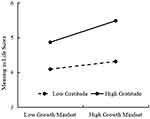

Since the interaction of growth mindset and gratitude on meaning in life was statistically significant, a further simple effect analysis showed that in the high-gratitude condition, the high-growth mindset group scored higher on the sense of meaning in life than the low-growth mindset group [F(1,132)=21.41, p<0.001]. However, in the low-gratitude condition, no discernible difference existed between the two groups in terms of meaning in life [F(1,132)=2.73, p(0.10)>0.05]. Further analysis showed that in the high growth-mindset condition, the sense of life meaning among the high-gratitude group was significantly higher than that among the low-gratitude group [F(1,132)=33.59, p<0.001], during the low-growth-mindset condition, the high-gratitude group reported a higher sense of life significance than the low-gratitude group [F(1,132)=76.91, p<0.001]. At the same time, the scores of the four test groups on meaning in life were statistically analysed (Table 4).

|

Table 4 Descriptive Statistics of Scores on Meaning in Life (N=136) |

The aforementioned findings indicate that the influence of growth mindset on individuals’ perception of life meaning is moderated by their level of gratitude. Specifically, people who possess both a high-development mindset and a high level of gratitude tend to experience a greater sense of meaning in life. Figure 3 shows the details.

|

Figure 3 Moderating effect of gratitude. |

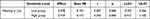

Experiment 1 aimed to investigate the relationship between growth mindset and the sense of significance in life, and the findings indicated that self-efficacy was a mediating factor. To further investigate whether gratitude moderates the connections among growth mindset and life meaning, process macro model 5 was adopted, taking meaning in life as the result variable. Among them, self-efficacy and gratitude are the mediating and moderating variables, respectively. The results are shown in Table 5. First, growth mindset significantly predicted self-efficacy (β=0.641, p<0.001), and meaning in life significantly predicted self-efficacy (β=0.221, p<0.01). The direct effect of growth mindset on meaning in life was not significant, which again verified the mediating role of self-efficacy. Second, gratitude and growth mindset had a significant interaction effect on meaning in life (β=0.681, p<0.01); that is, gratitude moderated the relationship between growth mindset and meaning in life. In further analysis, the direct effects of growth mindset on individuals’ meaning in life varied with the gratitude conditions (Table 6). In the low-gratitude condition, the direct effect of growth mindset on meaning in life was not significant (95% CI [−0.301, 0.456]). In the high-gratitude condition, the direct effect of growth mindset on individuals’ meaning in life was significant (95% CI [0.413, 1.105]), indicating that with the increase in individuals’ levels of gratitude, the impact of growth mindset on meaning in life demonstrated a clear rising trend. Finally, Figure 4 presents the model diagram.

|

Table 5 Regression Analysis (N=136) |

|

Table 6 Direct Effects of Growth Mindset on Meaning in Life Across Gratitude Levels (N=136) |

|

Figure 4 Moderated mediation models. Notes: ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01. |

In conclusion, Study 2 further explored the mechanism of action by which growth mindset affects meaning in life and fitted a moderating mediator model. The results of the study once again validated Hypotheses H1 and H2 and supported Hypothesis 3, which states that gratitude moderates the direct relationship between growth mindset and meaning in life. Previous studies have shown that individuals’ implicit thinking is not easily perceived in everyday life, but it has a positive impact on their psychology and behaviour; those who have a growth mindset can recognize their own abilities and are more likely to achieve their goals and appreciate their own significance and value.65,66 Coping theory suggests that individuals with a high propensity for gratitude are better able to use resources to satisfy their psychological needs, work hard to achieve their goals, believe more strongly in their ability to change their current situation, and easily realize the meaning and value of life when they succeed.67 Compared with previous studies, this study is innovative because it explored the relationship through a behavioural experimental approach and identified the psychological mechanisms and moderating variables through which growth mindset affects sense of meaning through a cognitive perspective. Experiment 2 improved the robustness and validity of the findings.

Discussion

Adolescents are in an important period of role unity formation. Increased recognition of one’s own abilities and values through the development of a growth mindset is important for enhancing one’s sense of meaning in life and maintaining the physical and mental health of adolescents. The investigation outcomes showed that growth mindset is a strong predictor of an individual’s sense of significance in life. Moreover, research has revealed that the association between growth mindset and meaning in life is fully mediated by self-efficacy. Additionally, gratitude, as a positive psychological quality, regulates the link between growth mindset and teenagers’ meaning in life. In the high-gratitude condition, the direct impact was significant, but in the low-gratitude condition, the direct effect was not significant. Therefore, an individual’s growth mindset may be directly interpreted as a positive cognition or a positive source of motivation, thus affecting junior high school students’ assessment of their self-competence. At the same time, when an individual maintains a sense of gratitude from time to time, he or she happens to be able to expand his or her level of cognition, which in turn better promotes the individual’s pursuit and endeavour of his or her goals in life and maintains the level of mental health. From the theoretical level, the contribution of this study is twofold. On the one hand, this study has enriched the scope of research on two major theories, focusing on the subjective initiative of individuals and the role of gratitude, providing an important theoretical basis for shaping the value and significance of individuals’ efforts to pursue and own their lives. Furthermore, this research advances the understanding of growth mindset and mental wellness. Meaning in life is one of the crucial indicators used to measure mental health.68 In this research, the prefactors that affect the meaning in life of individuals were found, which has important reference significance for other studies.

In previous research, most scholars have widely revealed the potential impact of mindset on academic achievement, emotions and behavioural responses.69,70 However, this study focuses on the effect of growth mindset on the health domain of individuals and finds that it has a positive relationship with individuals’ meaning in life, which supports hypothesis 1. This result is similar to the author’s previous research results.71 The difference is that previous studies used questionnaires, while this study used experimental methods to verify the causal relationship between the two. Regarding the reasons behind this, the theory of social cognition stresses the individual’s subjective agency and holds that the individual’s cognitive capacity plays a crucial part in it.72 Such individuals strive to face the environment and current situation actively rather than passively through self-management and then work to accomplish their objectives and realize a sense of value in life. Therefore, when individuals have a growth mindset, they often believe that their ability is plastic, thinking that they are fully capable of changing the previous inherent state or situation, and when faced with challenges, they will then attempt to alter their perspective by adopting appropriate strategies to address problems and achieve their goals.73 As a result, individuals might feel more satisfied with their lives and those of others, as well as have a greater feeling of purpose and importance.74 Overall, the objective of this research is to empirically examine the influence of positive cognitive beliefs on adolescents’ perceptions and experiences of meaning in life. It builds upon prior research and contributes to the literature on growth mindset within the domain of health.

Notably, the results of the mediating effect analysis indicated that self-efficacy served as a complete mediator in the association between development mindset and meaning in life. However, the direct impact of growth mindset on the sense of meaning in life was found to be nonsignificant, providing partial support for Hypothesis 2. Self-efficacy was impacted by growth mindset, which is somewhat consistent with previous findings.75 Self-efficacy significantly predicts meaning in life, which is consistent with Chang’s findings.76 We can explain this result by examining the following points. First, the current main effects model of growth mindset suggests that the formation of a growth mindset has a generally beneficial effect and improves an individual’s mental health.77 However, the growth mindset is only a kind of implicit idea, which is not easily detectable by oneself or others, and it takes a developmental process from the idea to the experience of pursuing it. That is, relying on some kind of intermediary factors to overcome all kinds of difficulties is the key to realizing the implicit idea,78 and self-efficacy happens to fit into that process. It is a kind of stable evaluation of individuals’ own ability, so that the growth mindset can affect oneself more stably and persistently through self-efficacy, which is a kind of stable cognitive evaluation.79 Therefore, it is through the stable cognitive evaluation of self-efficacy that the growth mindset can have a more stable and lasting impact on one’s experience and pursuit of the meaning of life. Second, this result can be understood based on self-determination theory. Individuals’ ways of thinking affect the generation and development of their behaviours, with the results varying with their ways of thinking.80 Further analysis shows that individuals with growth mindsets tend to have strong motivation or curiosity that drives them to explore new things. In the face of setbacks, they often hold the coping style of mastering goals, regard difficulties or tasks as springboards for their own improvement and believe that they have the ability to solve problems;81 that is, they exhibit high self-efficacy. As a positive psychological protective factor, when individuals have high beliefs in their own ability, they often have a strong sense of control when pursuing their self-set goals and consider that they are competent and assured to control and achieve these goals. When their goals are achieved, they experience a strong sense of value. Important sources of personal meaning in life include a sense of worth and mastery.82 Third, while most of the previous studies measured it as a trait, in the present study growth mindset was induced as a state, and the subjects were only briefly initiated into growth mindset, the above provides an explanation for why the direct effect of growth mindset on the sense of meaning in life is not significant. Thus, as an imperceptible and implicit way of thinking, the growth mindset needs to be expressed in the individual’s understanding and expression of the meaning of life through the mediation of self-efficacy. In summary, the present study has determined that the growth mindset has the potential to impact an individual’s perception of life meaning, with self-efficacy serving as a mediating factor in this relationship.

The moderating effect of gratitude indicates that the relationship between a growth mindset and meaning in life is related to individual positive psychological qualities. Simple effect analysis shows that a growth mindset promotes a sense of life meaning for those with high gratitude, but the direct effect is not significant for those with low gratitude. Hypothesis 3 is partially supported. The findings presented in this study contribute to the body of research by further elucidating the moderating influence of positive psychological traits on the association between cognitive beliefs and emotional well-being.83 The outcomes of this research prove that after a growth mindset is initiated through manipulation, the mechanism by which gratitude moderates effects is robust and strong, meaning that it is particularly effective in influencing meaning in life. The likely reason for this is that gratitude was measured as a trait rather than a state feeling.84 This also provides some explanation as to why the direct effect of growth mindset in influencing the sense of meaning in life is only possible under conditions of high gratitude. In addition, it can also be explained in terms of the following. First, starting from the promotion hypothesis of the protective-protective factor model,85 the two protective factors of a long growth mindset and gratitude reinforce each other. Adolescents who exhibit a high level of gratitude are more prone to benefit from the adoption of a growth mindset. Second, drawing on the broaden-and-build theory of gratitude, gratitude as a positive psychological quality or emotion can increase individuals’ cognitive levels and thus produce a positive response.86 Therefore, individuals with high gratitude have more flexible cognition and ways of thinking. High-growth-minded individuals have a greater belief that capabilities can be developed, changed and shaped.87 Third, China has advocated the culture of filial piety since ancient times. Chinese teenagers have been in this cultural background for a long time, and most of them have a heart of gratitude to society, their parents and nature. Therefore, compared with individuals with low gratitude levels, individuals with high gratitude levels are motivated to pursue and strive for their own goals to repay the favours they have received. In this case, an individual’s positive cognitive thinking is reinforced, and they are therefore more motivated to control their behaviour or take positive action to achieve their goals. Therefore, they tend to feel the meaning and value of life more easily.88,89 Based on the above discussion, it is easy to understand that growth mindset can significantly predict the perceptions and attempts to acquire meaning in the lives of individuals with high gratitude.

Furthermore, culture influences the way people perceive the world. This research study was conducted with Chinese regional culture as a backdrop. The results enrich localized research on the connection between growth mindset and sense of meaning in life and provide reference value for other scholars to explore in different cultural contexts. On the one hand, according to Sun et al90 growth mindset has cross-cultural differences; that is, Eastern students are more likely to believe that academic success can be attained through diligence, and they hold a malleable attitude towards academic success, whereas intellectual malleability is not as well recognized as in Western students. On the other hand, influenced by traditional Chinese culture advocating a humanistic spirit and social values such as democracy, civilization, harmony and dedication, Chinese teenagers tend to have a sense of mission and responsibility, and when teenagers have higher cultural self-confidence, they have a stronger sense of meaning.91 Therefore, it is worth considering whether teenagers’ understanding of meaning in life varies with cultural background. It can be inferred that due to the differences in cultural background, different adolescents have different understandings of a growth mindset and meaning in life, which may eventually affect their perceptions and pursuance of life meaning. Thus, the above provides a plausible explanation for the need to continue exploring the link among adolescent growth mindset and the value of one’s own life in other cultural contexts in depth.

Practical Implications

When adolescents have high growth mindsets, they can perceive meaning and value in life more easily. Therefore, teachers, parents and adolescents themselves should be aware of the potential value of shaping positive perceptions for the healthy growth of individuals throughout their lives. Previous studies have shown that the theory and intervention system of a growth mindset are relatively mature. Therefore, educators can learn from previous mature materials to shape the growth mindset of adolescents through thematic classroom interventions, group counselling interventions and image interventions to improve the ability of adolescents to cope with challenges.92 In addition, because teenagers are in an important period of developing a world outlook and outlook on life and value formation, they will be influenced by the way their teachers think. Therefore, schools also need to build a team of growth mindset-oriented teachers, and teachers should consciously help these students internalize the belief that intelligence can be shaped and pass on growth mindset-oriented values to students from the aspects of language, behaviour and emotional attitude, such as through sayings such as “failure is the mother of success” and “effort is more important than talent”. More importantly, students should endeavour to enhance their sense of self-worth, discover their own shining points and increase their self-confidence, which in turn will help them to better shape their growth mindset.

Adolescents’ sense of self-efficacy has an important function in bridging growth mindset and the possession and pursuit of life meaning. Therefore, educators need to emphasize how crucial self-efficacy is in the processes. In accordance with Bandura’s idea of self-efficacy,93 the four important factors affecting self-efficacy are self-experience, vicarious experience, verbal persuasion and emotional arousal. Adolescents themselves should improve their self-efficacy by recalling their own successes, thereby discovering their own strengths and awakening their courage and determination to overcome difficulties. At the same time, they can also look to their peers as role models and learn from the successes of others to help them achieve their ultimate goals. For teachers and parents, whether in classroom teaching or daily life, positive feedback and evaluation should be given to students according to the actual situation as much as possible so that students can obtain affirmation and support and gradually recognize their own behaviours and abilities. Therefore, a high sense of self-efficacy among adolescents is conducive to improving their individual adaptability and action ability. When they achieve their goals, they regard their actions as valuable and thus have a high meaning experience and perception.

Adolescents’ growth mindsets and meaning are influenced by their gratitude levels. It has been shown that individuals’ gratitude levels are closely associated with positive psychological health, such as happiness and social responsibility;94,95 when individuals feel more happiness and sense of responsibility, they will find their existence to be valuable. Therefore, it is also indispensable to cultivate gratitude in teenagers. Filial piety culture, as an important part of Chinese national culture, reflects the importance of giving thanks to education, as in ancient times. In actual school life, gratitude education should be carried out from the simple to the deep. On the one hand, schools can set up gratitude cultural corridors and campus media to promote gratitude so that students can change in a subtle way. On the other hand, teachers and parents should pay close attention to internalizing gratitude cognition in teenagers and carry out practical activities related to the theme of gratitude so that teenagers can fundamentally generate positive attitudes towards life and have good emotional experiences to activate their life source power. Previous research has also shown that the gratitude journaling method is beneficial for enhancing individuals’ subjective emotions.96 Thus, for adolescents themselves, they can keep a diary to record the gratitude events that happened to them or share them with others, thus helping them to shape their gratitude.

Research Limitations and Future Prospects

Although this study has made some achievements, it also has several shortcomings. First, in terms of the objects of study, due to the limitations of this study sample, only Chinese adolescents were taken as research objects. Previous scholars have found that individuals’ understandings of meaning in life vary with their cultural backgrounds.97 Therefore, in the future, we should expand the scope of our research sample to include adolescents from other cultures (eg, the West) to explore whether there are different results in their growth mindset in terms of their understanding and perception of the meaning of life. Second, in the research process, we used self-reports to measure adolescents’ meaning in life, without using other indicators, such as teachers’, friends’ and parents’ evaluations of aspects of the participants’ lives, which should be accounted for in future experiments. Third, in terms of research content, this study investigated only the overall dimension of meaning in life, without subdividing it into the dimensions of seeking meaning and having meaning. Therefore, it is unclear whether there is a difference in the effect of growth mindset on the two dimensions of sense of meaning in life. In view of this, meaning in life should be separated into the two dimensions of having meaning and pursuing meaning in the future to verify the relationships between growth mindset and these individual factors. Fourth, in terms of research results, although teenagers’ sense of meaning in life can be improved by manipulating their growth mindset, this change may only be a temporary psychological experience. In the future, teenagers’ cognition and understanding of meaning in life should be shaped by periodic group counselling or a series of courses. Fifth, in terms of research variables, previous studies have shown that when individuals are in different stressful scenarios, their perception of life may change, so in the future, we can consider stressful scenarios as moderating variables to explore the psychological mechanisms by which growth mindset affects the sense of meaning in life.98

Conclusion

Based on the discussion thus far, this study finds that adolescent growth mindset is an important protective factor for meaning in life. Specifically, growth mindset and meaning in life are significantly positively correlated, and self-efficacy fully mediates the impact of growth mindset on meaning. In addition, gratitude moderates these relationships, but only at high gratitude levels was the direct effect of growth mindsets on meaning in life significant. Therefore, parents, teachers and counsellors should help students acquire a sense of self-efficacy by shaping their growth mindsets or cultivating gratitude to effectively enhance their perceptions, understanding and pursuit of meaning in life.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethical Approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Henan Normal University (Approval Code: 2022CJY052; Approval Date: 20220915). Written informed consent was provided by all participants. We also obtained written informed consent from the parents of participants under the age of 18 in this study.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants and their parents included in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the article editor and anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions. Thanks to all the participants for their support for this study.

Funding

This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project ID. 72304088), and Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project of Henan Province, China (Project ID. 2022CJY052).

Disclosure

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Liu C, Zhang B. The development of the western liberal education tradition. J Higher Educ. 2015;36(04):74–78.

2. Shen Q, Jiang S. Life meaning and well-being in adolescents. Chin Mental Health J. 2013;27(08):634–640. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1000-6729.2013.08.015

3. Zhong N. The status quo and influencing factors of the sense of meaning in life of high school freshmen. J Res Educ Ethnic Minorit. 2015;26(03):87–94. doi:10.15946/j.cnki.1001-7178.2015.03.014

4. Zhang Z, Yi L, Huang L. The lack of meaning and spiritual crisis behind the “lying down” of young people. Philosoph Anal. 2022;13(01):89–101. doi:10.3969/j.issn.2095-0047.2022.01.007

5. Wolf S. Meaning in Life and Why It Matters. Princeton University Press; 2012.

6. Steger MF, Frazier P, Oishi S, Kaler M. The meaning in life questionnaire: assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. J Couns Psychol. 2006;53(1):80. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80

7. Jia L, Shi C. Study on college students mental health and its education from the view of meaning in life. Heilonqj Res Higher Educ. 2007;161(09):142–145. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1003-2614.2007.09.051

8. Steger MF. Making meaning in life. Psychol Inq. 2012;23(4):381–385. doi:10.1080/1047840X.2012.720832

9. Deci EL, Ryan RM. Self-determination theory. Handbook Theor Soc Psychol. 2012;1(20):416–436. doi:10.4135/9781446249215.n21

10. Zhao H, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Heng S. Review on the mindset and its relationship with related concepts concerning creativity. Sci Technol Prog Pol. 2020;37(11):153–160. doi:10.6049/kjjbydc.Q201908461

11. Huang X, Zhang J, Hudson L. Impact of math self-efficacy, math anxiety, and growth mindset on math and science career interest for middle school students: the gender moderating effect. Europ J Psychol Educ. 2019;34:621–640. doi:10.1007/s10212-018-0403-z

12. Yu X, Wang S. Effect of ego-identity on meaning in life of high school students: positive psychological capital and career adaptability as chain mediator. Psychol Techniq Applic. 2023;11(05):291–300. doi:10.16842/j.cnki.issn2095-5588.2023.05.004

13. Liu Y, Zhang X, Zhu C, Su R. Research on meaning of life from the perspective of positive psychology. Chin J Spec Educ. 2020;245(11):70–75. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1007-3728.2020.11.011

14. Arslan G, Yıldırım M. Coronavirus stress, meaningful living, optimism, and depressive symptoms: a study of moderated mediation model. Aust J Psychol. 2021;73(2):113–124. doi:10.1080/00049530.2021.1882273

15. Xiang Y, Yuan R. Why do people with high dispositional gratitude tend to experience high life satisfaction? A broaden-and-build theory perspective. J Happiness Stud. 2021;22:2485–2498. doi:10.1007/s10902-020-00310-z

16. Dweck CS. Mindsets: developing talent through a growth mindset. Olympic Coach. 2009;21(1):4–7.

17. Dweck C. Carol Dweck revisits the growth mindset. Educ Week. 2015;35(5):20–24.

18. Zhao H, Liu X, Qi C. “want to learn” and “can learn”: influence of academic passion on college students’ academic engagement. Front Psychol. 2021;12:697822. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.697822

19. Macnamara BN, Rupani NS. The relationship between intelligence and mindset. Intelligence. 2017;64:52–59. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2017.07.003

20. Hu C, Wang C, Liu W, Wang D. Depression and reasoning ability in adolescents: examining the moderating role of growth mindset. Front Psychol. 2022;13:636368. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.636368

21. Török L, Szabó ZP, Orosz G. Promoting a growth mindset decreases behavioral self-handicapping among students who are on the fixed side of the mindset continuum. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):7454. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-11547-4

22. Zhao H, Xiong J, Zhang Z, Qi C. Growth mindset and college students’ learning engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic: a serial mediation model. Front Psychol. 2021;12:621094. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.621094

23. Chen C. Can a growth mindset improve adolescents’ academic literacy? J Cent Chin Normal Univer. 2022;61(05):167–177. doi:10.19992/j.cnki.1000-2456.2022.05.016

24. Kondratowicz B, Godlewska-Werner D. Growth mindset and life and job satisfaction: the mediatory role of stress and self-efficacy. Health Psychol Rep. 2022. doi:10.5114/hpr/152158

25. Wang J, Song J, Cao Z, Qi S. An empirical research on the effects of managers’ growth mental model to career success. Chin J Manag. 2015;12(09):1319–1327. doi:10.3969/i.issn.1672-884x.2015.09.008

26. Berg JM, Wrzesniewski A, Grant AM, Kurkoski J, Welle B. Getting unstuck: the effects of growth mindsets about the self and job on happiness at work. J Appl Psychol. 2023;108(1):152. doi:10.1037/apl0001021

27. Yu T, Pan X, Li J, et al. Impacts of growth mindset on health: effects, mechanisms and interventions. Chin J ClinPsychol. 2022;30(04):871–875. doi:10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2022.04.023

28. Steger MF, Kashdan TB, Sullivan BA, Lorentz D. Understanding the search for meaning in life: personality, cognitive style, and the dynamic between seeking and experiencing meaning. J Pers. 2008;76(2):199–228. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00484.x

29. Diao C, Zhou W, Huang Z. The relationship between primary school students’ growth mindset, academic performance and life satisfaction: the mediating role of academic self-efficacy. Stud Psychol Behav. 2020;18(04):524–529. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1672-0628.2020.04.014

30. Wong PT. Meaning management theory and death acceptance. In: Existential and Spiritual Issues in Death Attitudes. Psychology Press; 2007:91–114.

31. Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191. doi:10.1016/0146-6402(78)90002-4

32. Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory. In: Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2022:1–7.

33. Zhang G, Xie Y, Meng Q. Growth mindset and entrepreneurial behavior tendency: an analysis based on the multi-dimensional moderator of entrepreneurial fear of failure. Sci Technol Prog Policy. 2022;39(10):32–40. doi:10.6049/kjjbydc.2021100266

34. Samuel TS, Warner J. “I can math!”: reducing math anxiety and increasing math self-efficacy using a mindfulness and growth mindset-based intervention in first-year students. Com Coll J Res Pract. 2021;45(3):205–222. doi:10.1080/10668926.2019.1666063

35. Liao M, Chen X. Self-schema and mental health. Chin J Clin Rehabilit. 2006;10(30):150–153. doi:10.3321/j.issn:1673-8225.2006.30.057

36. Abdel-Khalek AM, Lester D. The association between religiosity, generalized self-efficacy, mental health, and happiness in Arab college students. Pers Individ Dif. 2017;109:12–16. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2016.12.010

37. Zhou X, Liu Y, Chen X, Wang Y. The impact of parental educational involvement on middle school students’ life satisfaction: the chain mediating effects of school relationships and academic self - efficacy. Psycholog Dev Educ. 2023;(05):691–701. doi:10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2023.05.10

38. Ma Y. Effect of interpersonal relationship on depression: the chain mediating effect of life satisfaction and life meaning. Chin J Health Psychol. 2022;30(10):1459–1463. doi:10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2022.10.004

39. McCullough ME, Emmons RA, Tsang JA. The grateful disposition: a conceptual and empirical topography. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002;82(1):112. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.82.1.112

40. Zhao G, Chen X. A study on the gratitude dimensions of middle school students. Psychol Sci. 2003;06:1300–1302. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1671-6981.2006.06.005

41. Fredrickson BL. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am Psychol. 2001;56(3):218. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.56.3.218

42. Lovell B, Wetherell MA. Social support mediates the relationship between dispositional gratitude and psychological distress in caregivers of autistic children. Psychol Health Med. 2023;1–11. doi:10.1080/13548506.2022.2162939

43. Liu Y, Zhang S, Liu L, Liu H. Gratitude and the meaning of life the multiple mediating modes of perceived social support and sense of belonging. Chin J Spec Educ. 2016;190(04):79–83. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1007-3728.2016.04.012

44. Lin L, Liu Y, Wang C, Jia X. The role of hopelessness and gratitude in the association between rumination and college students’ suicidal ideation: a moderate mediation model. Stud Psychol Behav. 2018;16(04):549–556. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1672-0628.2018.04.017

45. Liao KYH, Wei M. Intolerance of uncertainty, acculturative stress, gratitude, and distress: a moderated mediation model. Couns Psychol. 2023;51(2):270–294. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1672-0628.2018.04.017

46. Schlegel RJ, Hicks JA, Arndt J, King LA. Thine own self: true self-concept accessibility and meaning in life. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2009;96(2):473. doi:10.1177/00110000221138

47. Van Tongeren DR, Green JD, Davis DE, Hook JN, Hulsey TL. Prosociality enhances meaning in life. J Posit Psychol. 2016;11(3):225–236. doi:10.1080/17439760.2015.1048814

48. Liu Y, Li Y, Zhang S, Liu L, Liu H. On the relationship between power and the sense of meaning of life. Chin J Spec Educ. 2016;198(12):85–90. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1007-3728.2016.12

49. O’Connor AJ, Nemeth CJ, Akutsu S. Consequences of beliefs about the malleability of creativity. Creat Res J. 2013;25(2):155–162. doi:10.1080/10400419.2013.783739

50. Halperin E, Russell AG, Trzesniewski KH, Gross JJ, Dweck CS. Promoting the Middle East peace process by changing beliefs about group malleability. Science. 2011;333(6050):1767–1769. doi:10.1126/science.1202925

51. Levy SR, Stroessner SJ, Dweck CS. Stereotype formation and endorsement: the role of implicit theories. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;74(6):1421. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1421

52. Gadgil S. Understanding the Interaction Between Students’ Theories of Intelligence and Learning Activitie. [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Pittsburgh; 2014.

53. Dweck CS. Self-Theories: Their Role in Motivation, Personality, and Development. New York, NY: Psychology Press; 1999.

54. Dweck CS. Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. Random house; 2006.

55. Orvidas K, Burnette JL, Russell VM. Mindsets applied to fitness: growth beliefs predict exercise efficacy, value and frequency. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2018;36:156–161. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.02.006

56. Zhang J, Zhao H, Li H, Ren Y. The process mechanism of team mindset on team scientific creativity. Stud Sci Sci. 2019;2019:1933–1943. doi:10.16192/j.cnki.1003-2053.2019.11.003

57. Wang X. Psychometric evaluation of the meaning in life questionnaire in Chinese middle school students. Chin J ClinPsychol. 2013;(05):764–767. doi:10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2013.05.008

58. Jiang J, Wang X, Yu J, Xiang H, Guo C. The influence of teachers’ caring behavior on middle school students’ academic stress: the mediating role of sleep quality and the moderating role of meaning in life. Stud Psychol Behav. 2023;21(02):260–265. doi:10.12139/j.1672-0628.2023.02.016

59. Lorenz T, Beer C, Pütz J, Heinitz K. Measuring psychological capital: construction and validation of the compound PsyCap scale (CPC-12). PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0152892. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0152892

60. Cheung FYL, Wu AM, Ching Chi L. Effect of job insecurity, anxiety and personal resources on job satisfaction among casino employees in Macau: a moderated mediation analysis. J Hospit Mark Manag. 2019;28(3):379–396. doi:10.1080/19368623.2019.1525332

61. Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. Guilford publications; 2017.

62. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Routledge; 2013.

63. He A, Liu H, Hui Q. Development of gratitude scale for adolescents based on trait gratitude. J East Chin Normal Univer. 2012;(02):62–69. doi:10.16382/j.cnki.1000-5560.2012.02.004

64. Hui Q, He A, Li Q. Relationship between gratitude and interaction anxiousness: across-lagged regression analysis. Educ Res Exper. 2018;183(04):84–87. doi:10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2015.04.039

65. Zhao H, Li Y, Wan L, Li K. Grit and academic self-efficacy as serial mediation in the relationship between growth mindset and academic delay of gratification: a cross-sectional study. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2023;3185–3198. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S421544

66. Azizli N, Atkinson BE, Baughman HM, Giammarco EA. Relationships between general self-efficacy, planning for the future, and life satisfaction. Pers Individ Dif. 2015;82:58–60. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.03.006

67. Wood AM, Joseph S, Linley PA. Coping style as a psychological resource of grateful people. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2007;26(9):1076–1093. doi:10.1521/jscp.2007.26.9.1076

68. Huang X, Gao X, Chen X, Sun J, Wu Q. Research progress in influencing factors and interventions of meaning in life of college students. Chin J Health Psychol. 2020;28(12):1900–1905. doi:10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2020.12.032

69. Yeager DS, Hanselman P, Walton GM, et al. A national experiment reveals where a growth mindset improves achievement. Nature. 2019;573(7774):364–369. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1466-y

70. Burnette JL, Knouse LE, Vavra DT, O’Boyle E, Brooks MA. Growth mindsets and psychological distress: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2020;77:101816. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101816

71. Zhao H, Zhang M, Li Y, Wang Z. The relationship between a growth mindset and junior high school students’ meaning in life: a serial mediation model. Behav Sci (Basel). 2023;13(2):189. doi:10.3390/bs13020189

72. Luszczynska A, Schwarzer R. Social cognitive theory. Fac Health Sci Publ. 2015;2015:225–251.

73. DeBacker TK, Heddy BC, Kershen JL, Crowson HM, Looney K, Goldman JA. Effects of a one-shot growth mindset intervention on beliefs about intelligence and achievement goals. Educ Psychol. 2018;38(6):711–733. doi:10.1080/01443410.2018.1426833

74. Zhang J, Zhou G, Deng Z, Zhang Y, Li Y. Effect of growth mindset on sense of educational acquisition in undergraduates: the chain mediating effect of grit and academic engagement. Chin J Health Psychol. 2023;31(06):953–960. doi:10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2023.06.030

75. Yeh YC, Ting YS, Chiang JL. Influences of Growth mindset, fixed mindset, grit, and self-determination on self-efficacy in game-based creativity learning. Educ Technol Soc. 2023;26(1):62–78. doi:10.1177/0886260517713716

76. Chang B, Fang J. Influence of negotiated fate on the meaning of ethnic college student’s live: on the mediating role of self-efficacy. J Res Educ Ethnic Minorit. 2020;31(02):142–148. doi:10.15946/j.cnki.1001-7178.2020.02.019

77. Hochanadel A, Finamore D. Fixed and growth mindset in education and how grit helps students persist in the face of adversity. J Inter Educ Res. 2015;11(1):47–50. doi:10.19030/jier.v11i1.9099

78. Cheng B, Chen P, Chen Y. Sports academy technical subject special students’academic achievement motivation and technical learning engagement: mediating effect of self-efficacy. J South Chin Norm Univ. 2022;47(04):96–106. doi:10.13718/j.cnki.xsxb.2022.04.014

79. Waddington J. Self-efficacy. ELT J. 2023;77(2):237–240. doi:10.1093/elt/ccac046

80. Gagné M, Deci EL. Self‐determination theory and work motivation. J Organ Behav. 2005;26(4):331–362. doi:10.1002/job.322

81. Huang Z, Shang K, Zhang J. Does growth mindset affect students’ social and emotional skills development: empirical analysis based on OECD social and emotional skills study. J East Chin Normal Univ. 2023;41(04):22–32. doi:10.16382/i.cnki.1000-5560.2023.04.002

82. Klein N. Prosocial behavior increases perceptions of meaning in life. J Posit Psychol. 2017;12(4):354–361. doi:10.1080/17439760.2016.1209541

83. Zhou G, Chen H, Guo H, Zhang Q, Tang H, Peng J. The moderating effect of trait gratitude between discrimination perception and social anxiety in the left-behind children. Chin J Behav Med & Brain Sci. 2019;28(10):921–924.

84. Wood AM, Maltby J, Stewart N, Linley PA, Joseph S. A social-cognitive model of trait and state levels of gratitude. Emotion. 2008;8(2):281. doi:10.1037/1528-3542.8.2.281

85. He N, Yan Y, Hui Q. The influence of subjective socioeconomic status on middle school students’ smartphone addiction: the moderating role of gratitude. Chin J ClinPsychol. 2021;21(03):510–513. doi:10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2021.03.013

86. Fredrickson BL. The broaden–and–build theory of positive emotions. Philosophical transactions of the royal society of London. Seri B Biolog Sci. 2004;359(1449):1367–1377. doi:10.1098/rstb.2004.1512

87. Zhou X, Ning B. the influence of growth mindsets on subjective well-being: a chain mediation model-A comparative study based on PISA 2018 data from China and Estonia. Educ Meas Evalu. 2022;256(05):100–112. doi:10.16518/j.cnki.emae.2022.05.011

88. Duckworth A, Gross JJ. Self-control and grit: related but separable determinants of success. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2014;23(5):319–325. doi:10.1177/0963721414541462

89. Bedford S. Growth mindset and motivation: a study into secondary school science learning. Res Papers Educ. 2017;32(4):424–443. doi:10.1080/02671522.2017.1318809

90. Sun X, Nancekivell S, Gelman SA, Shah P. Growth mindset and academic outcomes: a comparison of US and Chinese students. Npj Sci Learn. 2021;6(1):21. doi:10.1038/s41539-021-00100-z

91. Bi C, Wu L, Zhao Y. Acquiring a sense of meaning: the alleviating effect of cultural confidence on depression and anxiety. J North Normal Univer. 2022;59(01):89–96. doi:10.16783/j.cnki.nwnus.2022.01.010

92. Miller DI. When do growth mindset interventions work? Trends Cogn Sci. 2019;23(11):910–912. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2019.08.005

93. Bandura A. Reflections on self-efficacy. Advan Behav Res Therap. 1978;1(4):237–269. doi:10.1016/0146-6402(78)90012-7

94. O’Connell BH, O’Shea D, Gallagher S. Examining psychosocial pathways underlying gratitude interventions: a randomized controlled trial. J Happiness Stud. 2018;19:2421–2444. doi:10.1007/s10902-017-9931-5

95. Wood AM, Froh JJ, Geraghty AW. Gratitude and well-being: a review and theoretical integration. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(7):890–905. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.005

96. Hui Q, Chen R, He A. Gratitude and mental health among junior school students: a cross-lagged regression analysis. Chin J ClinPsychol. 2023;43(12):13–16. doi:10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2015.04.039

97. Pan J, Wong DFK, Chan CLW, Joubert L. Meaning of life as a protective factor of positive affect in acculturation: a resilience framework and a cross-cultural comparison. Inter J Intercul Relat. 2008;32(6):505–514. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2008.08.002

98. Zhang Z, Wang J, Duan W. The impact of adolescents’ character strengths on quality of life in stressful situations during COVID-19 in China: a moderated mediation approach. J Evid Based Soc Work. 2023;1–15. doi:10.1080/26408066.2023.2231438

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.