Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 17

The Effect of Group Identity on Chinese College Students’ Social Mindfulness: Testing a Moderated Mediation Model

Received 13 July 2023

Accepted for publication 14 December 2023

Published 22 January 2024 Volume 2024:17 Pages 237—248

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S430375

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Mei-Chun Cheung

Xinyi Guo, Lin You

Center for Collaborative Innovation of Civilization Practice in New Era, Jiangxi Normal University, Nanchang, Jiangxi, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Lin You, Center for Collaborative innovation of Civilization Practice in New Era, Jiangxi Normal University, Nanchang, Jiangxi, 330022, People’s Republic of China, Tel +86 791-88122985, Email [email protected]

Purpose: The current study examined the effect of group identity on social mindfulness, how awe mediates this effect, and lastly how empathy may moderate the various indirect pathway.

Methods: A total of 2041 Chinese college students were recruited from different universities or colleges to complete the questionnaire including group identity scale, awe scale, empathy scale and social mindfulness scale. This study was conducted using random and convenient sampling, as well as SPSS and its plugin PROCESS as a statistical tool.

Results: The present study showed that group identity was positively associated with awe and social mindfulness. Awe was positively associated with social mindfulness. Empathy further moderated the relationship between group identity and awe, awe and social mindfulness, as well as group identity and social mindfulness.

Conclusion: The findings of this study shed light on a correlation between group identity and social mindfulness. Furthermore, this study emphasizes the practical importance of intervening in the empathy level of students who have poor empathy in order to increase their social mindfulness.

Keywords: group identity, social mindfulness, empathy, awe

Introduction

Today is the digital information age, with an advanced network. According to the 49th Statistical Report on the Development of the Internet in China, the number of Chinese netizens had reached 1.032 billion by December 2021, with an Internet penetration rate of 73.0%.1 With the advancement of Internet technology, social media has brought convenience to people and greatly changed their lifesty les. However, false information, internet fraud, pornography and violence, Internet addiction, etc., have a negative impact on people’s ideological and moral awareness. Among them, cyber-violence is particularly concerning. College students, as one of the main users of social media on the Internet, are the group with the largest potential to be negatively impacted by cyber-violence,2 such as personal attacks, intentional abuse, unauthorized disclosure of other people’s information, as well as telephone and information harassment. Therefore, it is especially important in this type of environment to cultivate college students’ social mindfulness.

Social mindfulness is the propensity for people to pay close attention during interpersonal communication to respect and protect others’ choices, needs, and rights.3 Some researchers define it as a fundamental orientation reflecting the motivational state and stable behavior, which can be triggered by interpersonal relationships or situations and can also be found in individuals as a personality variable.4 The theory of regulatory focus holds that the expression of social mindfulness is influenced by individuals’ inferences about altruistic choices,5 which stems from different interaction patterns caused by different cultural backgrounds.6 In traditional Chinese culture, expressions reflecting the concept of social mindfulness have always existed, such as “kindness to others” and “benevolence”.7,8 “Social mindfulness” is regarded as the concrete embodiment of practicing the principle of “mindfulness” in practical life, which means that individuals consciously pay attention to and respect the needs of others’ choices and protect their right to choose in interpersonal interaction. It should be noted that promoting and cultivating mindfulness has always been one of the core aims of education in China.9 As the younger generation, college students shoulder the responsibility of the future social development of the country, whose healthy growth and interpersonal harmony are of great positive significance to universities and even the entire society.10,11 Meanwhile, the level of social mindfulness can just reflect the degree of harmony in individual interpersonal relationships and their mental health literacy. Additionally, the negative effects of social media must be extremely concerned, such as cyber-violence, which can greatly limit the development of social mindfulness. Given the potential harm of cyber-violence that may exist in social media, an exceptional chance to investigate the functions of awe and empathy as precursors to the promotion of social mindfulness in the era of comprehensive Internet was made possible by enhancing group identity.

Group Identity and Social Mindfulness

Individuals’ proclivity to perceive themselves, their groups, or organizations as intertwined, with shared qualities, flaws, successes, failures, and destinies, is a well-documented phenomenon. The term “group identity” or “organizational identification” refers to this perceptual state.12–15 Studies on intergroup cognition have found that people are more likely to display empathy, be friendly, and cooperate with members of their own group. People, on the other hand, exhibit bias, apathy, and rivalry among groups or for out-group members.16,17 The disparities in attitudes and behaviors between internal and external groups make us wonder whether psychological differences will spread to influence the inconsistencies, prejudices, and rejections between entire social groups.

And it certainly is. The identity of the interaction object and the identity relationship between the inter-actors influence social beneficent behavior motivation in the same way that it influences prosocial behavior motivation. According to research, people are more inclined to maintain a greater degree of social mindfulness behavior for friends than for strangers or imagined rivals.4,18 Based on our review of the literature, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Group identity is positively related to social mindfulness.

Awe as a Mediator

Awe is the emotion associated with the perceived vastness and the need for accommodation. It refers to the emotional feeling of surprise that occurs when humans are presented with something beyond our existing understanding.19 Currently, the majority of psychologists believe awe is dominated by positive consequences, with self-transcendence being one of the key psychological impacts of awe.20 According to empirical studies,21 individuals with stronger self-transcendence pay more attention to and concern about societal problems, and have a higher acceptance degree to external groups.22 However, in the opinion of the internal and external group effect and social identity theory, individuals will give more positive evaluation and benevolence to their in-group and its members than the out-group in order to obtain positive group identity and improve self-value.23 This result reminds the researcher of a possible link between awe and group identity. Although not yet tested, it is reasonable to expect that awe serves as a mediator between group identity and social mindfulness. In the following section, previous research findings would be reviewed to support above arguments.

First of all, on the basis of hedonic adaptation theory, frequent exposure to an environment that enhances an emotion promotes its accumulation, which can not only improve the baseline level of the emotion but also encourage individuals to continuously accumulate the psychological effects brought by the emotion,24 and result in shifts in attitudes and behaviors.25 In order to encourage the openness of individual thought and prosocial conduct,26,27 awe can boost one’s sense of connection to others and self-insignificance.19,28 Moreover, social consciousness and tolerance for going against social norms can be raised by enhanced sentiments of interpersonal connectedness, mental openness, and a prosocial cultural milieu.29 As a result, we propose the following theories:

Hypothesis 2: Awe is positively related to a) group identity and b) social mindfulness. Hypothesis 3: Awe mediates the effect of group identity on social mindfulness.

Empathy as a Moderator

Empathy is the ability to understand the emotions of others (ie, cognitive empathy) and share emotional states (ie, affective empathy).30 Empathy might make people feel closer to the out-group and its members. Although most research on group effects has discovered that in-group and out-group effects are typically manifested as in-group favoritism or out-group derogation, researchers have discovered that when presented with the same classification of in-group and out-group, sometimes individuals prefer the out-group and sometimes even make stricter demands on the internal group,31 implying that some moderating variables may play a role in the relationship between individuals.

Simultaneously, empathy can boost life satisfaction and pleasure while also promoting pleasant emotional experiences.32 As a result, the sense of group border established by group identity might make individuals open under the effect of pleasant experience. As a result, empathy has the capacity to dissolve the barriers between the inner and outer groups, increase the relationship between all group members, reduce or alter individuals’ low regard for members of the outer group, and develop respect for both the inner and outer groups.

Awe enables people to focus on greater entities rather than on self-centered and self-fulfilling improvement and expansion.28,33 Awe, like pride, remorse, pleasure, happiness, and other external items or connected decisions, is a type of self-awareness.34,35 Self-transcendence and conference are components of awe.20 When people identify disparities between stimuli and their existing mental schema or knowledge, they must change or construct new schemas to explain them.19,36 Unlike treating the current stimulus as an existing one during assimilation, the reference pattern does not change.36–38 During the compliance phase, emphasis is focused on the deviations of current spines from established patterns, and patterns are updated or recreated to address these deviations.36,37 Therefore, compliance needs to include breaking or revising the psychological structures and forming new ones. This reminds us that the sense of awe enables people to face their own existing schema in some group rules, however, additional psychological elements may play a role in the breakdown process of this psychological schema.

Empathy is about directing one’s intentionality toward the other’s intentionality.39 In other words, compassion is the process in which one guides his own mental schemas to others, Individual mental schemas are also a process of change. Thus, we posit the following:

Hypothesis 4: Empathy magnifies the effect of group identity on awe.

A recent study has found a positive correlation between awe and empathy.40 In the meantime, studies on brain imaging have also discovered that awe and empathy have similar brain mechanisms, such as reducing the self-related default network and increasing the activation degree of the outward-directed frontoparietal network.41 These findings point to a strong relationship between awe and empathy. Empathy plays an important role in promoting many types of prosocial behavior,42 as well as enhancing a higher frequency of voluntary behavior and more helping behavior.43,44 Neuroimaging studies have also revealed that brain regions activated by empathy, such as the insula and the associated temporoparietal area, are positively correlated with charitable giving,45 indicating a neural mechanism by which empathy promotes prosocial behavior. Thus, we posit the following:

Hypothesis 5: Empathy magnifies the effect of awe on social mindfulness.

Adult altruism has revealed that preference is given to one’s group or close kin over distance or non-kin. Facial resemblance or sharing the same family name is an important kinship cue that has been shown to increase helping behavior.46,47 Overarching ethnic and cultural characteristics, as well as in-group self-definitions and identities, are all important factors. There is an “empathy gap” based on group affiliation: in-group identities, in accordance to research. People are less likely to comprehend and match the emotions of out-group members, to assist them when they are in need, and even to value their lives as high as those of in-group members, according to research on the “empathy gap” based on group affiliation.48

The strongest predictor of altruism is trait empathy.49,50 A lack of empathy may then lead to increased objectification and schematization of those not belonging to one’s group, which would result in a decrease in social mindfulness. Thus, we posit the following:

Hypothesis 6: Empathy magnifies the effect of group identity on social mindfulness.

The Present Study

Taken together, the current study first examined whether awe mediates the relation between group identity on social mindfulness (Figure 1). Secondly, we also examined the moderating effect of empathy on the indirect (paths z1 and z3) and direct paths (path z2) in this model.

Method

Participants

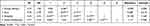

A questionnaire survey was carried out using convenience sampling method with participants from universities in China. A total of 2113 Chinese college students from different universities or colleges participated the present study. The essential data gathering activity was completed during the positive psychological survey conducted at the college where the author and his buddies worked. All participants began answering the questionnaire with informed consent and were advised that they might opt out at any point. The criteria for unqualified samples were less than 60 seconds to complete questionnaires with a total of 33 questions and regularity of answers, such as the same score in each item or a regular pattern of scores (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, etc.). After removing invalid observations (eg, missing data or other errors), 2041 participants (67.4% female) were included in the final analysis. The sample was composed of mostly students from undergraduate colleges (covers all types of undergraduate colleges, such as public and private) (49.9%) and higher vocational colleges (all public) (50.1%) comprised the majority. Detailed demographic information is displayed in Table 1. All participants provided informed consent and voluntarily participated based on an assurance of confidentiality and anonymity. The data collectors were well-trained researchers to ensure the standardization of the data collection process. A quick response (QR) code or link to the questionnaires was delivered to the students after informing them of the purpose of our survey and obtaining their informed consent. Each participant could scan the QR code or click the link to access a website to complete the questionnaires. After completing the survey, the participants were given small gifts for participating. This study was performed in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the university the first author was affiliated with. See the participant demographics (Table 1) for details.

|

Table 1 Demographic Characteristics of Participants |

Research Instruments

Group Identity Scale

Group identity was measured by the group identity scale,51 which consists of 10 items (eg “This organization’s successes are my successes”). Each item was rated on 7-point scale (1= complete inconsistency 7 = complete consistency). Higher total scores indicated higher levels of group identity. In the present study, Cronbach’s α for the scale was 0.91 in the current study. Furthermore, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) suggested that the model fitted the data well: χ²=57.181, df=28, RMSEA=0.074, CFI=0.975, TLI=0.960, SRMR=0.046.

Awe Scale

The Chinese version of the Awe scale was used to assess participants’ levels of awe.26,52 The Awe scale consisted of 6 items (eg, “I am often in awe”). All items were measured on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = completely disagree, 7 = completely agree), α = 0.86. Furthermore, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) suggested that the model fitted the data well: χ²=12.501, df=6, RMSEA=0.096, CFI=0.979, TLI=0.947, SRMR=0.038.

Empathy Scale

The Chinese version of the Basic Empathy Scale was used to measure empathy.30,53 The Chinese revised Basic Empathy Scale consisted of 20 items (eg, “Seeing others helpless, I would like to help them”) and included two dimensions: cognitive empathy and affective empathy. Individuals rated each item on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Not at all, 5 = Exactly like me), α = 0.73. Furthermore, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) suggested that the model fitted the data well: χ²=119.053, df=43, RMSEA=0.062, CFI=0.931, TLI=0.947, SRMR=0.058.

Social Mindfulness Scale

Social mindfulness was measured by the social mindfulness scale,6 which consists of 17 items (e g “I can often put myself in other people’s shoes”). Each item was rated on 5-point scale (1 = completely disagree 5 = completely agree). Higher total scores indicated higher levels of social mindfulness. In the present study, Cronbach’s α for the scale was 0.85 in the current study. Furthermore, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) suggested that the model fitted the data well: χ²=332.075, df=113, RMSEA=0.075, CFI=0.928, TLI=0.914, SRMR=0.066.

Data Analysis

Tests of normality revealed that the study variables showed no significant deviation from normality (ie, Skewness < |3.0| and Kurtosis < |10.0|).54 Descriptive statistics were first calculated. PROCESS Models 4 and 59 macro for SPSS were used to test the mediation and moderated mediation models with 5000 random sample bootstrapping confidence intervals (CIs).55 All variables were standardized prior to being analyzed.

Results

Common Method Deviation Test

Common variance analysis was performed to the four questionnaires through Harman’s one-factor method. Principal component analysis of all variables extracted 10 eigenvalues greater than 1. The first factor explained 17.01% of the variance, which was less than the critical value of 40%, demonstrating that the common method bias effect was not problematic in the present study.56

Preliminary Analysis

The Means, SDs and Pearson correlations are presented in Table 2. Group identity was positively correlated with awe, empathy and social mindfulness. Awe was positively correlated with empathy and social mindfulness. Gender were positively correlated with empathy and social mindfulness. Except the negative correlation of group identity, awe and empathy, there’s no correlation in social mindfulness and type of university. Here, all findings supported our given Hypotheses 1 and 2.

|

Table 2 Normality Test and Pearson Correlation Analyses |

Analysis of Awe as a Mediator

To test the mediating effect of awe (Figure 1), five linear regression models were run (Table 3). Group identity was positively related to awe (Models 2, 4) and social mindfulness (Models 1, 3). Social mindfulness was positively predicted by awe (Models 3, 5). Accordingly, awe mediated the effect of group identity on social mindfulness (0.07, SE = 0.02, 95% CI = [0.04, 0.10], p < 0.001), accounting for 36.09% of the total effect. All findings supported our given Hypotheses 1–3.

|

Table 3 Linear Regression Models |

At this point, the results of the path coefficients of the moderated mediation model in this study have been obtained. Detailed information is shown in Figure 2.

Analysis of Empathy as a Moderator

Model 4 (Table 3) examined the moderation effect of empathy on path a1 while Model 5 examined the moderation effect on paths b1 and c1 (Figure 1). Results showed a significant, negative interaction between social identity and empathy on awe (Model 4). The interaction effect is visually plotted in Figure 3A. Simple slope tests revealed that social identity had a significant positive effect on awe in low-level empathy (bsimple = 0.16, t = 6.03, p < 0.001) but not high-level empathy (bsimple = 0.03, t = 1.10, p = 0.27).

Empathy negatively interacted with both awe and group identity (Model 5) in predicting social mindfulness (Figure 3B and C). Simple slope tests showed that awe had a significant positive effect on social mindfulness in those with both low- (bsimple = 0.56, t = 24.79, p < 0.001) high-levels of empathy (bsimple = 0.27, t = 11.21, p < 0.001). However, the effect is noticeably smaller among those with high levels of empathy (Figure 3B). Lastly, simple slope tests showed that group identity had a significant predictive effect on social mindfulness in those with low- (bsimple = 0.11, t = 4.58, p < 0.001) but not high-level empathy (bsimple = 0.03, t = 1.09, p = 0.28) (Figure 3C).

Discussion

Our findings supported our hypotheses about the magnitude and direction of the effects. Consistent with previous findings,57 our findings also revealed that Chinese college students have different tendencies to the interests of internal and external groups based on their own group identity. Despite the different levels of awe, they maintain a high level of social mindfulness for both internal and external group members. Furthermore, the moderating effect of empathy was reflected in the mechanisms used to result in social mindfulness.

Mediating Effect of Awe

The findings indicate that awe mediates the relationship between group identity and social mindfulness, supporting our initial hypothesis that group identity is positively correlated with awe and awe is positively correlated with social mindfulness. The findings of this study point to a promising future: cultivating college students’ sense of group identity may increase their awe and prosocial behavior. From an evolutionary standpoint, Keltner believe that awe is induced by prototypes (such as authoritative people),19 which aids in the individual’s compliance with group norms and social rules, promotes the individual’s understanding of social mindfulness, and makes the individual more willing to act in the interest of helping others. This reminds us that strengthening the guidance of college students’ group identity and assisting them in the formation of correct group norms and social values can help college students form positive awe and then have the desire to help others with positive thoughts.

This study discovered that awe can directly predict social mindfulness, that is, the greater the trait of awe is, the greater the degree of social mindfulness is, which is consistent with previous research findings.58,59 Simultaneously, the incentive-help hypothesis proposes that positive information with high strength will motivate people and increase their willingness to help others. As a result, the more awe experience individuals have in everyday life, the more incentives they have to promote their prosociality.60

According to the Expanded Constructional Theory of Positive Emotions, positive emotions can increase people’s psychological and social resources,61 and cause them to have a more positive perception of others.62 Awe, as a positive emotion, can improve an individual’s psychological resources, and its external motivation function also helps promote attention to others, making it easier for individuals to pay attention to the situation of others.63 Cultivating a sense of awe can be integrated into college students’ mental health courses or other disciplines to improve social mindfulness and promote more prosocial behaviors such as reducing cyber-attacks.64 Cyber-attack behavior is a derivative form of traditional attack behavior and a new form of harm based on the development of the Internet, which can have a serious impact on the physical, mental, and social functions of recipients.65

According to the findings of this study, cultivating and enhancing people’s awe (such as awe of life and nature) can increase social kindness. Because awe can cause people to transcend national identity boundaries,66 it can break the bias effect of internal groups (that is, individuals’ evaluation of internal groups is significantly higher than that of external groups, reducing prosocial behavior of external groups),67 promote empathy and prosocial behavior of external groups, and then promote international cooperation in cyberspace construction.

The Moderating Effect of Empathy

Empathy tempered the effect of group identity on awe, as well as the effect of group identity and awe on social mindfulness. And the moderated patterns of empathy for the three pathways were similar. Our results showed that empathy moderated the relationship between group identity and awe. Especially in the relationship between group identity and awe, social mindfulness was significant for college students with low empathy. While it became not significant for high empathy among college students, this result is similar to that of previous studies.68 In addition, the relationship between awe and social mindfulness was significant for college students with low empathy, while it became weaker for high empathy among college students. That is, group identity and awe have a good effect on social mindfulness, and empathy is a protective factor that enhances both of these effects. However, low empathy has a higher protective effect than high empathy. Three things that can prevent hostility are group identity, amazement, and empathy. The “protective-protective model” exclusion hypothesis states that one protective factor lessens the impact of another protective factor on the outcome variable.69 There may be an explanation for this discovery. People with a high level of empathy may focus less on their welfare but more on the welfare of others who are having difficulties.70 Therefore, people who have experienced a high level of empathic priming may behave more purely altruistically and may have a harder time falling into the state of out-group exclusion to account for the benefits of their prosocial behavior, regardless of whether they perceive awe in the group identity process. When a person’s empathy is high, his feeling of awe and social mindfulness is already in a favorable state, making it difficult to demonstrate the positive effects of group identity. People with low empathetic priming may perceive other people’s problems objectively, and they might not have as great an ability to sense other people’s emotions and states as people with high empathic priming. Therefore, those with inadequate empathic priming may have weaker social mindfulness when they are influenced by group identity because they focus more on the advantages of the in-group and have a reduced experience of positive feelings like awe. Individuals with low levels of identity, therefore, displayed lower awe and social mindfulness than those with high levels of identity under the situation of low state empathy.

According to our hypothesis, the greater the empathy, the stronger the positive correlation between group identity and awe. Although group identity is positively related to awe, the interaction suggests that group identity should be combined with empathy to maximize awe emotions. Even though they are strangers, humans tend to mimic or imitate the specific physical postures and mannerisms of their interaction partners. One explanation for this behavior is that people mimic in order to increase empathy.71 According to this theory, mimicry is the first step in the process of emotional contagion in which a person imitates the expressions, postures, and behaviors of another, and the resulting muscle contractions provide feedback to the brain, allowing one to feel the corresponding emotion.72 Group membership can have an impact on mimicry. Making norms about out-group empathy more visible can also reduce bias in intergroup empathy, which means that empathy can enhance group identity. If just one member of the out-group expresses empathy for the in-group, in-group members are more likely to humanize the entire out-group.73 Thus, empathy helps people overcome prejudices that exist between members of the in-group and those of the out-group, strengthen group identity, and help in-group members get a greater sense of understanding and respect for members of the out-group as well as awe.

Furthermore, the greater people’s empathy is, the greater the positive influence awe has on social mindfulness, which is consistent with our hypothesis and the literature’s expectations.28,74,75 Empathy and awe help individuals in dealing with the different social challenges that humans face when living in groups. Empathy motivates people to help others in need and deepens social ties when they are needed the most. Awe helps individuals fold into cohesive collectives by leading to a reduced estimation of one’s importance. These emotions foster healthy social relationships, binding individuals together through prosociality.

Together, these factors suggest that empathy has a dubious place in human sociality. On the one hand, a group’s coherence and stability depend on a variety of factors, including not only its members’ common behaviors, habits, norms, and traditions but also their fundamental sense of belonging to the group as a whole. Sharing each other’s feelings is a crucial precondition for identifying with others, as Hobson and Zahavi have noted, as it entails not just experiencing the same emotion but also reciprocal awareness of jointly partaking in an emotional experience.76,77 Repeated exposure to this kind of sharing strengthens one’s sense of belonging to the group as a whole. While empathy does not always equate to genuinely experiencing the same feeling, it certainly encourages or even facilitates it. As a result, empathy emerges as a crucial tool for creating social cohesion, both at the primary inter affective level, where it encourages bonds of attachment, and at the higher level of perspective-taking, norms, and regulations. On the other hand, empathy is a crucial component of social awareness because it helps people feel more connected with others and reduces psychological distance.78,79 The empatruism hypothesis contends that people are more likely to feel motivated to help others when they devote empathic attention to others who are suffering.80

Limitations and Future Directions

There are some limitations to the current investigation. Future research may employ experimental and/or longitudinal designs to further test the provided model because the cross-sectional design of the study restricts causal inference. This is important because social mindfulness may appear after the social impact event has occurred. Additionally, because all variables are evaluated by self-report, there may be bias in the responses and impacts of social desirability. The results should therefore be confirmed with larger, more complete, or even representative samples. Thirdly, the sample of the present study was solely made up of Chinese college students, which may have limited its application to a larger population and urged that future studies utilizing different types of samples be carried out.

Conclusion

In summary, although further research is needed, this study represents an important step in exploring how group identity may be related to social mindfulness among Chinese college students. The results show that awe serves as one mechanism by which group identity is associated with social mindfulness. Interaction effects provide positive implications, showing that they may be coupled with group identity to further increase the awe of internal and external groups while promoting social mindfulness. Future research can help the field design targeted interventions for tackling specific areas of concern, such as the network attack, as well as future issues to come.

Data Sharing Statement

All raw data supporting the results will be freely accessible and can be requested from the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of Jiangxi Normal University on October 9, 2020, in line with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol number is IRB-JXNU-PSY-2020029. All participants gave written informed permission for this research.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the reviewers for their helpful comments and feedback on this article.

Funding

This study was supported by Key Project of Jiangxi Provincial Social Science “14th Five Year Plan” Fund (22ZZ01).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest for this work.

References

1. China Internet Network Information Center. The 49th statistical report on the development of internet in China. China Inter Network Informat Center. 2022;2022:81.

2. Wu X. Analysis of the relationship between college students’ cyber violence news and cyber violence behavior in social media. International. J Front Soc. 2022;4(11):40–44. doi:10.25236/IJFS.2022.041108

3. van Doesum NJ. Social Mindfulness. Ipskamp drukkers BV; 2016.

4. van Lange PAM, van Doesum NJ. Social mindfulness and social hostility. Curr Opin Behav Sci. 2015;3(4):18–24. doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.2014.12.009

5. Higgins ET. Beyond pleasure and pain. Am Psychologist. 1997;52(12):1280–1300. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.52.12.1280

6. Tian Y, Wang L, Xu Y, Jiao LY. Psychological structure of social mindfulness in Chinese culture. Acta Psychol Sin. 2021;53(9):1003–1017. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1041.2021.01003

7. Xiao LB. The unity of opposites between “benevolence” and “righteousness” in Chinese traditional morality. Moral Civilisat. 2006;1:16–19. doi:10.13904/j.cnki.1007-1539.2006.01.004

8. Zhang YF, Huang SJ. The ecological civilization implication of Chinese traditional ethics. J Renmin Univer Chin. 2009;5:87–92.

9. Feng A. Research on the Current Situation and Cultivation Strategies of Friendly Views among College Students in the New Era [M.A. Thesis]. Shenyang: Shenyang Agricultural University; 2023.

10. Su M, He W, Fan L, Xu XW. Current situation of college students’ social responsibility and training mechanism. Guide Sci Educ. 2015;23:15–16.

11. Qiu YJ, Jian QC. The individual requirements and subject limits of the development of minority college students in the perspective of Marxist philosophy. Ethn Stud Rev. 2018;2018:1.

12. Tajfel H. Instrumentality, identity and social comparisons. In: Taifel H, editor. Social Identity and Intergroup Relations. Cambridge University Press; 1982:483–507.

13. Turner JC. Social identification and psychological group formation. In: Tajfel H, editor. The Social Dimension: European Psychology. Cambridge University Press; 1984:518–538.

14. Kelman HC. Processes of opinion change. Public Opin Q. 1961;25:57–78. doi:10.1086/266996

15. Tolman EC. Identification and the post-war world. J Abnorm Psychol. 1943;38:141–148. doi:10.1037/h0057497

16. Halevy N, Bornstein G, Sagiv L. “In-group love”and “out-group hate” as motives for individual participation in intergroup conflict: a new game paradigm. Psychol Sci. 2008;19(4):405–411. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02100.x

17. Hein G, Silani G, Preuschoff K, Batson CD, Singer T. Neural responses to ingroup and outgroup members’ suffering predict individual differences in costly helping. Neuron. 2010;68(1):149–160. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.003

18. Van Lange PAM, Joireman J, Parks CD, Van Dijk E. The psychology of social dilemmas: a review. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 2013;120(2):125–141. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2012.11.003

19. Keltner D, Haidt J. Approaching awe, a moral, spiritual, and aesthetic emotion. Cognit Emot. 2003;17(2):297–314. doi:10.1080/02699930302297

20. Bonner ET, Friedman H. A conceptual clarification of the experience of awe: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Humanist Psychol. 2011;39(3):222–235. doi:10.1080/08873267.2011.593372

21. Schwartz SH, Sagiv L, Boehnke K. Worries and values. J Pers. 2000;68(2):309–346. doi:10.1111/1467-6494.00099

22. Schwartz SH. Basic values: how they motivate and inhibit prosocial behavior. In: Mikulincer M, Shaver PR, editors. Prosocial Motives, Emotions, and Behavior: The Better Angels of Our Nature. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2010:221–241.

23. Otten S, Moskowitz GB. Evidence for implicit evaluative in-group bias: affect-biased Spontaneous trait inference in a minimal group paradigm. J Exper Soc Psychol. 2000;36(1):77–89. doi:10.1006/jesp.1999.1399

24. Armenta C, Bao KJ, Lyubomirsky S, Sheldon KM. Is lasting change possible? Lessons from the hedonic adaptation prevention model. In: Sheldon KM, Lucas RE, editors. Stability of Happiness. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2014:57–74.

25. Erickson TM, McGuire AP, Scarsella GM, et al. Viral videos and virtue: moral elevation inductions shift affect and interpersonal goals in daily life. J Positive Psychol. 2018;13(6):643–654.

26. Shiota MN, Keltne D, John OP. Positive emotion dispositions differentially associated with Big Five personality and attachment style. J Posit Psychol. 2006;1(2):61–71. doi:10.1080/17439760500510833

27. Perlin JD, Li L. Why does awe have prosocial effects? New perspectives on awe and the small self. Perspectives Psychol Sci. 2020;15(2):291–308. doi:10.1177/1745691619886006

28. Piff PK, Dietze P, Feinberg M, Stancato DM, Keltner D. Awe, the small self, and prosocial behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2015;108(6):883–899. doi:10.1037/pspi0000018

29. Harrington JR, Gelfand MJ. Tightness-looseness across the 50 United States. PNAS. 2014;111(22):7990–7995. doi:10.1073/pnas.1317937111

30. Jolliffe D, Farrington DP. Development and validation of the basic empathy scale. J Adolesc. 2006;29(4):589–611. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.08.010

31. Abrams DJ, Marques M. Pro-norm and anti-norm deviance within and between groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78(5):906–912. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.78.5.906

32. Luo L, Zou R, Yang D, Yuan J. Awe experience triggered by fighting against COVID-19 promotes prosociality through increased feeling of connectedness and empathy. The J Posit Psychol. 2023;18(6):866–882. doi:10.1080/17439760.2022.2131607

33. Jiang L, Yin J, Mei D, Zhu H, Zhou X. Awe weakens the desire for money. J Pac Rim Psychol. 2018;12:1–10. doi:10.1017/prp.2017.27

34. Silvia PJ, Abele AE. Can positive affect induce self-focused attention? Methodological and measurement issues. Cognit Emot. 2002;16(6):845–853. doi:10.1080/02699930143000671

35. Ferguson MA, Branscombe NR. Collective guilt mediates the effect of beliefs about global warming on willingness to engage in mitigation behavior. J Environ Psychol. 2010;30(2):135–142.

36. Fiedler K. Affective states trigger processes of assimilation and accommodation. In: Martin LL, Clore GL, editors. Theories of Mood and Cognition: A User’s Guidebook. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2001:85–98.

37. Piaget J. Genetic Epistemology. Columbia University Press; 1970.

38. Bless H, Clore GL, Schwarz N, Golisano V, Rabe C, Wolk M. Mood and the use of scripts: does a happy mood really lead to mindlessness? J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;71(4):665–679. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.71.4.665

39. Englander M, Folkesson A. Evaluating the phenomenological approach to empathy training. J Humanist Psychol. 2014;54(3):294–313. doi:10.1177/0022167813493351

40. van Mulukom V, Patterson RE, Van Elk M. Broadening your mind to include others: the relationship between serotonergic psychedelic experiences and maladaptive narcissism. Psychopharmacology. 2020;237(9):2725–2737. doi:10.1007/s00213-020-05568-y

41. Xin F, Lei X. Competition between frontoparietal control and default networks supports social working memory and empathy. Soc Cognit Affective Neurosci. 2015;10(8):1144–1152. doi:10.1093/scan/nsu160

42. Tamir M, Schwartz SH, Cieciuch J, et al. Desired emotions across cultures: a value based account. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2016;111(1):67–82. doi:10.1037/pspp0000072

43. Zhou H, Zhang B. The relationship between narcissism and empathy and prosocial behavior. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2010;18(2):228–231.

44. Xing SF, Wang DY, Lin CD. The impact and psychic mechanism of media violence on children and their aggressive behavior. J East China Norm Univ. 2015;33(3):71–78.

45. Tusche A, Böckler A, Kanske P, Trautwein FM, Singer. T. Decoding the charitable brain: empathy, perspective taking, and attention shifts differentially predict altruistic giving. J Neurosci. 2016;36(17):4719–4732. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3392-15.2016

46. Hunt M. The Compassionate Beast: What Science is Discovering About the Humane Side of Humankind. New York: Anchor Books; 1990.

47. Okasha S. Biological altruism. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy; 2013.

48. Kunstman JW, Plant EA. Racing to help: racial bias in high emergency helping situations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;95(6):1499–1510. doi:10.1037/a0012822

49. Hajek A, König HH. Level and correlates of empathy and altruism during the Covid-19 pandemic. Evidence from a representative survey in Germany. PLoS One. 2022;17(3):e0265544. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0265544

50. Pan Y, Liang S, Shek DT. Attachment insecurity and altruistic behavior among Chinese adolescents: mediating effect of different dimensions of empathy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(16):10371. doi:10.3390/ijerph191610371

51. Mael F, Ashforth BE. Alumni and their alma mater: a partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. J Organizational Behav. 1992;13(2):103–123.

52. Dong R, Peng KP, Yu F. Positive emotions: awe. Adva Psychol Sci. 2013;21(11):1996–2005. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1042.2013.01996

53. Geng Y, Xia D, Qin B. The basic empathy scale: a Chinese validation of a measure of empathy in adolescents. Child Psychiatry Human Dev. 2012;43(4):499–510. doi:10.1007/s10578-011-0278-6

54. Kline TJB. Psychological Testing: A Practical Approach to Design and Evaluation. Sage publications; 2005.

55. Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2013.

56. Podsakoff PM, Mackenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

57. Wen X. The Influence of individual group identity on tolerance of Internal and external groups: fear of emotional adjustment [M.A. Thesis]. Kunming: Yunnan Normal University; 2022.

58. Guan F, Chen J, Chen OT, Liu LH, Zha YZ. Awe and prosocial tendency. Curr Psychol. 2019;38(4):1033–1041. doi:10.1007/s12144-019-00244-7

59. Li JJ, Dou K, Wang YJ, Nie YG. Why awe promotes prosocial behaviors? The mediating effects of future time perspective and self-transcendence meaning of life. Frontiers in Psychology. 2019;10:1140. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01140

60. Liang JP, Guo RL, Liu ZB. Does accidental awe motivate people to donate? J Northeast Univ. 2020;22(4):38–46.

61. Fredrickson BL. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am Psychologist. 2001;56(3):218–226. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

62. Nelson C. Appreciating gratitude: can gratitude be used as a psychological intervention to improve individual well-being. Couns Psychol Rev. 2009;24(3−4):38–50. doi:10.53841/bpscpr.2009.24.3-4.38

63. Stellar JE, Gordon AM, Piff PK, et al. Self-transcendent emotions and their social functions: compassion, gratitude, and awe bind us to others through prosociality. Emotion Rev. 2017;9(3):200–207. doi:10.1177/1754073916684557

64. Mou FY. The impact of awe on moral judgment [M.A. Thesis]. Guiyang: Guizhou Normal University; 2023.

65. Zhai YH. The influence and Intervention of College Students’ Trait Anger and Rumination on Cyber Attack Behavior [M.A. Thesis]. Harbin: Harbin Engineering University; 2021.

66. Yaden DB, Iwry J, Slack KJ, et al. The overview effect: awe and self transcendent experience in space flight. Psychol Consciou. 2016;3(1):1–11.

67. Hewstone M, Rubin M, Willis H. Intergroup bias. Annu Rev Psychol. 2002;53:575–604. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135109

68. Canioz EK, Coskun H. The impact of social identity and empathy on helping behavior: the moderator role of empathy. Int J Sci Technol Res. 2019;5(12):314–323.

69. Wang Y, Zhang W, Peng J, Mo B, Xiong S. The relations of attachment, self-concept and deliberate self-harm in college students. Psychol Explor. 2009;5:56–61.

70. Kou Y, Xu H. The two functions of empathy on decision-making of prosocial behavioral. Psychol Expl. 2005;3:73–77.

71. Chartrand TL, van Baaren RB. Human mimicry. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 2009;41:219–274.

72. Stel M, van Baaren RB, Vonk R. Effects of mimicking: acting prosocially by being emotionally involved. Eur J Social Psychol. 2008;38(6):965–976.

73. Gubler JR, Eran Halperin E, Hirschberger G. Humanizing the outgroup in contexts of protracted intergroup conflict. J Exp Political Sci. 2015;2:36–46. doi:10.1017/xps.2014.20

74. Vanman EJ. The role of empathy in intergroup relations. Curr Opin Psychol. 2016;11:59–63. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.06.007

75. Lu T, McKeown S. The effects of empathy, perceived injustice and group identity on altruistic preferences: towards compensation or punishment. J Appl Social Psychol. 2018;48(12):683–691. doi:10.1111/jasp.12558

76. Hobson JA, Hobson RP. Identification: the missing link between joint attention and imitation? Dev Psychopathol. 2007;19(2):411–431. doi:10.1017/S0954579407070204

77. Zahavi D. You, me, and we: the sharing of emotional experiences. Journal of. Conscious Stud. 2015;22(1–2):84–101.

78. Shiota MN, Keltner D, Mossman A. The nature of awe: elicitors, appraisal and effects on self-concept. Cognit Emot. 2007;21(5):944–963. doi:10.1080/02699930600923668

79. Van Cappellen P, Saroglou V. Awe activates religious and spiritual feelings and behavioral intentions. Psychol Relig Spiritual. 2012;4(3):223–236. doi:10.1037/a0025986

80. Batson C, Shaw L. Evidence for altruism: toward a pluralism of prosocial motives. Psychol Inq. 1991;2(2):107–122. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli0202_1

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.