Back to Journals » Clinical Interventions in Aging » Volume 17

The Chinese Short Version of the Activities-Specific Balance Confidence Scale: Its Validity, Reliability, and Predictive Value for Future Falls in Community-Dwelling Older Adults

Authors Zhang D , Tian F, Gao W, Huang Y, Huang H, Tan L

Received 4 July 2022

Accepted for publication 24 August 2022

Published 3 October 2022 Volume 2022:17 Pages 1483—1491

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S380921

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Zhi-Ying Wu

Dongting Zhang,1,* Fengmei Tian,2,* Wenjun Gao,2 Yvfeng Huang,3 Hui Huang,2 Liping Tan2

1Department of Nursing, the First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Hefei, People’s Republic of China; 2Department of Nursing, the Second Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University, Suzhou, People’s Republic of China; 3School of Nursing, Soochow University, Suzhou, People’s Republic of China

*These authors contributed equally to this work

Correspondence: Hui Huang; Liping Tan, Department of Nursing, the Second Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University, No. 1055, Sanxiang Road, Suzhou, 215004, People’s Republic of China, Tel +86-15312187852 ; +86-13962514643, Email [email protected]; [email protected]

Purpose: To examine the reliability and validity of the Chinese short version of the Activities-specific Balance Confidence scale (ABC-6), and its predictive value for prospective falls in community-dwelling older adults.

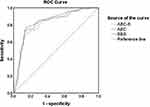

Patients and Methods: A total of 391 community older adults completed the prospective study. Internal consistency reliability, test-retest reliability, structural validity and discriminant validity were analyzed. To determine the accuracy of ABC-6 total score in predicting falls, a receiver operating characteristic curve analysis was performed, and comparisons with the Activities-specific Balance Confidence scale (ABC-16) and Berg Balance Scale (BBS) were made.

Results: Excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.938) and test-retest reliability (ICC=0.964, 95% CI: 0.947– 0.977) were found for the ABC-6. Exploratory factor analysis suggested that ABC-6 had a one-factor structure (explained variance, 68.30%). The optimal cutoff value, sensitivity and specificity of ABC-6 to distinguish fallers from non-fallers was ≤ 60.00%, 70.83% and 84.26%, respectively, and there was no significant difference in the predictive value among the ABC-6, ABC-16, and BBS.

Conclusion: The Chinese version of the ABC-6 scale was a valid and reliable tool for measuring self-perceived balance confidence in community-dwelling older adults, and can be used as an effective assessment tool to predict future falls.

Keywords: activities-specific balance confidence scale, Chinese version, older adults, falls, predictive

Introduction

Falls are the second leading cause of accidental injury deaths and are considered to be the main health concern with the aging population globally.1 Approximately 30% of people over 65 years fall at least once each year.2,3 Falls can not only result in serious physical harm or disability,4 but may also have enduring detrimental effects on the mental health of the older adults (ie fall-related anxiety and loss of confidence), and have been found to be associated with low health-related quality of life.5 The direct medical expenses per year in China exceed 5 billion yuan, and the social costs are as high as 16–80 billion yuan.6 Therefore, the prevention of falls, especially the identification of people at high risk of falling, is important for the health of the older adults.

The assessment of fall risk is the basis and premise of fall intervention. And in the fall-risk assessment, it was an important aspect that psychological factors as well as physical factors affect falling.7,8 Although as many as 132 factors have been identified related to fall,9 previous studies have focused on the role of physiological factors in falls, and the importance of such factors may have been exaggerated.10 Fall-related psychological factors, may be equally or even more important for identifying people at risk of falling.10,11 The representative psychological factor is fall-related self-efficacy, or balance confidence. Balance confidence is conceptually similar to falls efficacy, which refers to people’s confidence and belief in their ability to avoid falling.12 It is worth noting that balance confidence is a measure of FOF, and they are two interrelated but different concepts.13 Compared with FOF, balance confidence can be more sensitive to detect early changes in balance, and was commonly used in predicting falls.12

The Activities-Specific Balance Confidence scale (ABC-16) is one of the most widely used tools to measure balance confidence.14 The scale includes 16 activities of daily living, such as walk around house, sweep the floor, and walk in crowded mall, which need complex posture control abilities (including posture stability and orientation) for adaptation to the complex environments to maintain balance.15,16 ABC-16 is a reliable assessment tool that has been adapted to several languages,17–20 as well as to various pathologies.21–23 However, it can take up to 20 minutes to properly complete the 16-item questionnaire. To improve time management in busy clinical and research settings, a short version of the ABC-16 scale (ABC-6) was developed, which contains the six most balance-challenging items in the original scale.24 The ABC-6 has a good level of reliability and validity in the community older adults, and has shown strong correlations with the ABC-16.25,26 However, its psychometric characteristics have not been verified in the elderly population in China. Furthermore, its predictive ability for future falls has not been fully explored.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the ABC-6, as well as its value for predicting future falls among community-dwelling older adults. Based on previous studies, we hypothesized that ABC-6 would be an effective tool for evaluating balance confidence in older adults from Chinese communities, and the ABC-6 and ABC-16 scales would have similar good predictive value for future falls.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

A prospective research design was used to determine the psychometric characteristics of ABC-6 and its predictive value for future falls. At baseline, participants completed the general information and ABC-16 scale via face-to-face interviews, and balance function was assessed using the Berg Balance Scale (BBS). Then, during the 6-month follow-up period, participants were interviewed by telephone at 3 and 6 months to collect information on the number of falls, if any, in the most recent 3 months. The definition of fall in this study was “unintentionally coming to the floor, ground or other lower level regardless of the cause”.27 Participants who had one or more falls during the follow-up period were classified as “fallers”, whereas individuals who did not have falls were classified as “non-fallers”. The Ethics committee of The Second Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University in Suzhou, China, approved the study (JD-LK-2020-073-01). The study protocol followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in Brazil 2013).

Participants

Participants were recruited from two community health centers in Suzhou, China, and 391 older adults were included in the study. Inclusion criteria were as follows: age ≥ 60 years; able to move on their own (with or without walking aids); provided signed written informed consent. Participants were excluded if they had cognitive impairment as assessed prior to the other assessments using the Mini cog (Mini-cog < 3);28 were unable to communicate properly or to perform balance function tests because of illness (eg, severe hearing or language disturbance, lower extremity surgery or joint replacement); or had major diseases or at the end of life. Participants who cannot accurately report their falls or failed to be followed up were excluded. Informed consent was obtained from the study participant.

Assessments

The ABC-16 and ABC-6 Scale

The ABC-16 was used to assess confidence in maintaining balance while performing 16 different daily activities, such as sweeping the floor or going to the mall alone. Participants were asked to rate their balance confidence on a scale of 0% (no confidence) to 100% (full confidence), and higher scores indicate greater confidence in balance.14 The ABC-6 consisted of the six most balance-challenging items in the ABC-16 scale, which were items 5, 6, 13, 14, 15, and 16.24 The total scores of ABC-16 and ABC-6 were the average of 16 and 6 items, respectively, and were reported as confidence percentages.

The Mini-Cog

All applicants filled out the mini-cog questionnaire before inclusion to ensure that they had normal cognitive function. The scale consists of two parts: remembering three unrelated words and clock-drawing test.29 The total score of the scale is 5, and a score ≥ 3 indicates the absence of dementia.28 The sensitivity and specificity of the mini-cog were 76–99% and 89%–93%,30 respectively, indicating a good predictive value for dementia. The mini-cog can be completed in 3 minutes, and the results are not affected by education level, language, or cultural background.

Berg Balance Scale

The BBS is considered the “gold standard” for assessing balance, and it can evaluate dynamic and static balance functions simultaneously. It consists of 14 tasks of varying difficulty, and each item is scored on a scale of 0–4.31 The maximum score is 56, and higher scores indicate better performance. The BBS has good sensitivity (78.3%) and specificity (83.3%) for predicting fall risk in the Chinese elderly population at a cut-off value of 48.5.32

Demographic Characteristics

General demographic information was measured at baseline, including gender, age, height, weight, body mass index, educational level, use of walking aids, number of falls in the past year, and number of chronic comorbidities. Questions were selected based on the literature and clinical experience.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive data are expressed as the mean and SD, counts, and percentages, as appropriate. Internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient and item-total correlations, with 0.6 ≤ α < 0.7 considered acceptable, 0.7 ≤ α < 0.9 considered good, and α ≥ 0.9 considered excellent.33 Test-retest reliability was evaluated in 40 of the 391 participants by re-administering the ABC-16 after 10–14 days. An intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) > 0.75 was considered acceptable and ICC > 0.90 indicated a very good level.34 Internal structure was examined by exploratory factor analysis, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity and the Keiser-Meyer-Olkin measure were used to assess the appropriateness for principal component analyses, with a minimum value of 0.60 recommended by Keiser-Meyer-Olkin as acceptable.35 Concurrent validity was determined by Spearman correlation coefficients with BBS.

Discriminant validity among fallers and non-fallers was examined by two-sample t-tests. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to determine sensitivity and specificity of the ABC-16 and ABC-6, and to compare their predictive value with that of the BBS. The actual fall status of participants was taken as the gold standard and the score of the scale as the test variable to plot the ROC curve. The area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity (Se), and specificity (Sp) were calculated and compared. The coordinate on the ROC curve when the Youden index reached the maximum was selected as the optimal cut-off value, which had a relatively balanced sensitivity and specificity.36 Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 25.0 and MedCalc 20.0.

Results

Of 420 questionnaires that were sent out, 408 were returned, and the response rate was 97.14%. During the follow-up period, 17 subjects dropped out, including 11 subjects with incorrect telephone information or no answer, and 6 subjects with poor communication. Finally, 391 subjects were included.

The mean age of the participants was 71.9 ± 6.52 years, and 52.9% were men. There were 48 (12.3%) subjects who experienced falls during the 6-month follow-up period and they were classified as “fallers”, whereas the remaining 343 (87.7%) subjects who did not fall were classified as “non-fallers”. Compared with non-fallers, fallers were more likely to have a positive history of falls in the previous 12 months from baseline testing (X2 = 15.69, P<0.001). The demographic characteristics of the subjects are shown in Table 1.

|

Table 1 Baseline Characteristics of Total Sample, Fallers, and Non-Fallers |

The total ABC-6 score showed good internal consistency, with Cronbach’s α = 0.938, which was similar to that of the ABC-16 (Cronbach’s α = 0.941). Further analysis showed that Cronbach’s α remained >0.9 after deleting each item. This was supported by the corrected item-total correlation coefficients, which ranged from 0.722 to 0.898. Both the ABC-6 and ABC-16 showed good test-retest reliability, with ICC values of 0.964 [95% confidence interval (95% CI= 0.947–0.977] and 0.941 (95% CI = 0.917–0.961), respectively. The ICC of each item of ABC-6 ranged from 0.832 to 0.947 (Table 2).

|

Table 2 Internal Consistency (Cronbach’s α), Corrected Item-Total Correlation (r), Test-Retest Reliability (ICC), and Factor Loadings for the Chinese Version of ABC-6 Scale |

In the internal structure analysis of ABC-6, Bartlett’s test of sphericity (P<0.001) and the Keiser-Meyer-Olkin measure (0.897) provided sufficient evidence for the appropriateness of factor analysis. One common factor was extracted by combining the results of exploratory principal component analysis and scree plot (Figure 1). All six items showed high loadings in one factor, which ranged from 0.734 to 0.895 (Table 2), and 68.30% of the total variance was explained. The correlation coefficient between ABC-6 and BBS was 0.729, and the correlation coefficient between ABC-16 and BBS was 0.743 (P<0.001).

|

Figure 1 Scree plot of the Chinese short version of the Activities-specific Balance Confidence scale. |

The mean total scores of ABC-6 (51.25 ± 21.58 vs 77.34 ± 20.26; P < 0.001) and ABC-16 (70.75 ± 15.39 vs 88.18 ± 12.83; P < 0.001) were significantly lower in the faller group than in the non-faller group. The ABC-6 scores were lower than the ABC-16 scores, but scores were highly correlated (r = 0.970, P<0.001). Except for items 1, 4, 5, and 7, the scores of other items differed significantly between the two groups (Table 3).

|

Table 3 Mean Value of the Chinese ABC-6 and ABC-16 Scales in the Faller and Non-Faller Group |

The ABC-6 scale demonstrated excellent overall accuracy for identifying future falls, with an AUC of 0.815 (95% CI: 0.773–0.853). The optimal cutoff value of the ABC-6 score for distinguishing fallers from non-fallers was ≤60.00%. At this cutoff value, the sensitivity and specificity were 70.83% and 84.26%, respectively, and the prediction accuracy was 82.61%. Similarly, the ABC-16 showed good predictive value for prospective falls, with an AUC of 0.825 (95% CI: 0.784–0.861), optimal cutoff value of 80.00%, sensitivity of 75.00%, and specificity of 84.84%. The comparison of ABC-6, ABC, and BBS showed that the AUC (0.837, 95% CI: 0.796–0.872), sensitivity (77.08%), and specificity (86.01%) of BBS at the cutoff value of 48 were slightly higher than those of ABC-6 and ABC-16, although there was no significant difference between any two scales (Figure 2).

Discussion

Based on the Chinese version of the ABC-16, this study explored the psychometric properties of ABC-6 and its predictive value for prospective falls in community-dwelling older adults. Nearly 16% of the participants reported a positive fall history in the previous 12 months, and approximately 12% experienced at least one fall during the 6-month follow-up period. As confirmed in the literature, the presence of a positive fall history was a risk factor for future falls. The results of the present study showed that the internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and discriminative power of ABC-6 was highly comparable with those of the ABC-16.

The ABC-6 exhibited excellent internal consistency (α = 0.938), which was comparable to that of the ABC-16 in the current study (α = 0.941) and the Chinese Mandarin version reported by Guan et al (α = 0.94);18 it was also comparable to the original English-language version (α = 0.96).14 The test-retest reliability of ABC-6 was also excellent (ICC = 0.964), similar to that of the Brazilian (ICC = 0.952)26 and German (ICC = 0.981)37 versions.

Exploratory factor analysis indicated that ABC-6 was unidimensional (explained variance, 68.30%), which was consistent with the results of Schott et al37 in older German adults. By contrast, two common factors were extracted from the Chinese ABC-16 (explained variance, 69.60%).18 This may be related to differences in difficulty between the 16 items in the ABC-16. ABC-6 and ABC-16 scores were positively correlated with the BBS, indicating that balance confidence may reflect balance ability to some extent.38,39 In addition to the BBS, other performance-based balance measures, such as the Timed Up and Go test, Timed one-leg stance test, and 10-meter timed walk test also showed strong correlations with ABC-6 or ABC-16 scores.37,39,40 These findings provide a theoretical basis for the application of the ABC-6 and ABC-16 to the risk assessment of falls in the older adults.

In the present study, the mean total scores of ABC-6 and ABC-16 scale were significantly different between the fallers and non-fallers, which was consistent with the results of Schott N et al.37 However, Schepens et al40 reported that the balance confidence of fallers was lower than that of non-fallers as measured by the ABC-6 scale, but there was no difference between the groups with the ABC-16. This discrepancy may be related to the fact that only 35 community older adults were included in that study, which markedly limited the results. In the diabetic population, the ABC-6 was more sensitive than the ABC-16 for detecting subtle differences in balance confidence.41 On the contrary, in patients with a lower extremity amputation, the ABC-16 was recommended42 and the ABC-16 with 5-option response format was also found an effective measure of balance confidence.43 In addition, because ABC-6 contains six of the most balance-challenging activities, its scores were significantly lower than that of the ABC-16. The additional ten items in the ABC-16 may exaggerate the overall confidence level and this was confirmed by the ceiling effect of the ABC-16 observed in one study.17 The current findings suggest that the ABC-6 and ABC-16 can both be applied to community-dwelling older adults, although their application to the population with specific diseases need further verification.

An AUC of 0.8 represents a reasonable and effective model.44 In this study, ABC-6 and ABC-16 showed almost the same AUC (0.815 and 0.825, respectively), indicating that both scales can be used as effective assessment tools for predicting falls in the older adults.

The optimal cutoff value of ABC-6 for distinguishing fallers from non-fallers was ≤60.00%. This was higher than the values of ≤44% reported from a cross-sectional study of the Brazilian version.26 For the ABC-16, the score ≤ 80.00% indicated a high risk of falling. However, two previous studies found that the optimal cutoff values of ABC-16 in were ≤ 67.00% and ≤ 58.13%,11,45 respectively, which were significantly lower than the current results. Such differences may due to the characteristics of the participants but not the reliability of the examination tool. In stroke patients, ABC-6 and ABC-16 also showed good fall prediction value with an AUC>0.77.46 Further analysis showed that the AUC, sensitivity, and specificity of the BBS (AUC=0.837, Se=77.08%, Sp=86.01%) were similar to those of the ABC-6 and ABC-16, and there was no statistically significant difference among the three scales. In the literature, the pooled sensitivity of BBS was 0.7 and the pooled specificity was relatively low, varying between 0.5 and 0.7.47 It is worth noting that the comparison of the fall predictive value of ABC-6, ABC-16 and BBS was the innovation of this study, and also enhanced the persuasion of the results. These findings indicated that the patients’ beliefs regarding their capabilities may be as important as the actual physical performance in fall risk assessment.48

Some limitations of the study should be noted. Although the research had a prospective study design and a high response rate, the follow-up period was only 6 months; a longer follow-up period would increase the power of the study. In addition, since there were no reports on the sensitivity and specificity of the Chinese version of ABC-6 in the literature, it was difficult to estimate the sample size according to the sample size calculation formula.49 However, the sample size of this study was relatively sufficient compared with other studies regarding this topic. Finally, the population included relatively healthy older adults, making it difficult to generalize the current findings to frail older people and populations with specific diseases.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Chinese version of the ABC-6 scale is a valid and reliable measure of balance confidence in community-dwelling older adults. Both the ABC-16 and ABC-6 scales can be used as effective predictive tools to identify the older adults at high risk of falling. The ABC-6 has shorter management time and may be more efficient in busy clinical or research settings. The present findings reveal the important role of fall-related efficiency in the risk of falls, and provide some ideas for the screening of elderly population at risk of falls, as well as the development of fall prevention strategies.

Acknowledgment

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Collaborators GMaCoD. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1459–1544. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1

2. Hu X, Qu X. Pre-impact fall detection. Biomed Eng Online. 2016;15(1):61. doi:10.1186/s12938-016-0194-x

3. Moreland B, Kakara R, Henry A. Trends in Nonfatal Falls and Fall-Related Injuries Among Adults Aged≥65 Years - United States, 2012-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(27):875–881. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6927a5

4. Australian Institute of Health Welfare. Injury in Australia: Falls. Canberra: AIHW; 2021.

5. Bjerk M, Brovold T, Skelton DA, Bergland A. Associations between health-related quality of life, physical function and fear of falling in older fallers receiving home care. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):253. doi:10.1186/s12877-018-0945-6

6. Zhang QL, Zhang L. Research progress of falls in the elderly. Chin J Gerontol. 2016;36(01):248–249.

7. Park EY, Lee YJ, Choi YI. The sensitivity and specificity of the Falls Efficacy Scale and the Activities-specific Balance Confidence Scale for hemiplegic stroke patients. J Phys Ther Sci. 2018;30(6):741–743. doi:10.1589/jpts.28.741

8. Park EY, Choi YI. Investigation of psychometric properties of the Falls Efficacy Scale using Rasch analysis in patients with hemiplegic stroke. J Phys Ther Sci. 2015;27:2829–2832. doi:10.1589/jpts.27.2829

9. Kwan MM, Close JC, Wong AK, et al. Falls incidence, risk factors, and consequences in Chinese older people: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(3):536–543. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03286.x

10. Landers MR, Oscar S, Sasaoka J, et al. Balance Confidence and Fear of Falling Avoidance Behavior Are Most Predictive of Falling in Older Adults: prospective Analysis. Phys Ther. 2016;96(4):433–442. doi:10.2522/ptj.20150184

11. Lajoie Y, Gallagher SP. Predicting falls within the elderly community: comparison of postural sway, reaction time, the Berg balance scale and the Activities-Specific Balance Confidence (ABC) scale for comparing fallers and non-fallers. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2004;38(1):11–26. doi:10.1016/S0167-4943(03)00082-7

12. Hadjistavropoulos T, Delbaere K, Fitzgerald TD. Reconceptualizing the role of fear of falling and balance confidence in fall risk[J]. J Aging Health. 2011;23(1):3–23. doi:10.1177/0898264310378039

13. Tinetti ME, Richman D, Powell L. Falls efficacy as a measure of fear of falling[J]. J Gerontol. 1990;45(6):239–P243. doi:10.1093/geronj/45.6.P239

14. Powell LE, Myers AM. The Activities-Specific Balance Confidence (ABC) Scale. J Gerontol a Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50(1):28–34. doi:10.1093/gerona/50A.1.M28

15. Yu HX, Wang ZX, Liu CB, et al. Effect of Cognitive Function on Balance and Posture Control after Stroke. Neural Plast. 2021;2021:6636999. doi:10.1155/2021/6636999

16. Leirós-Rodríguez R, Romo-Pérez V, García-Soidán JL, et al. Percentiles and reference values for the accelerometric assessment of static balance in women aged 50-80 years. Sensors. 2020;20(3):940. doi:10.3390/s20030940

17. Elboim-Gabyzon M, Agmon M, Azaiza F. Psychometric properties of the Arabic version of the Activities-Specific Balance Confidence (ABC) scale in ambulatory, community-dwelling, elderly people. Clin Interv Aging. 2019;14:1075–1084. doi:10.2147/CIA.S194777

18. Guan Q, Han H, Li Y, et al. Activities-Specific Balance Confidence (ABC) Scale adapted for the mainland population of China. Clin Rehabil. 2012;26(7):648–655. doi:10.1177/0269215511427748

19. Schott N. German adaptation of the “Activities-Specific Balance Confidence (ABC) scale” for the assessment of falls-related self-efficacy. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2008;41(6):475–485. doi:10.1007/s00391-007-0504-9

20. Marques AP, Mendes YC, Taddei U, et al. Brazilian-Portuguese translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the Activities-Specific Balance Confidence (ABC) scale. Braz J Phys Ther. 2013;17(2):170–178. doi:10.1590/S1413-35552012005000072

21. Alsubheen SA, Beauchamp MK, Ellerton C, et al. Validity of the Activities-specific Balance Confidence Scale in individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2022;16(6):689–696. doi:10.1080/17476348.2022.2099378

22. Alghwiri AA, Khalil H, Al-Sharman A, et al. Psychometric properties of the Arabic Activities-Specific Balance Confidence scale in people with multiple sclerosis: reliability, validity, and minimal detectable change. Neuro Rehabilitation. 2020;46(1):119–125. doi:10.3233/NRE-192900

23. Paker N, Bugdayci D, Demircioglu UB, et al. Reliability and validity of the Turkish version of Activities-specific Balance Confidence scale in symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2017;30(3):461–466. doi:10.3233/BMR-150335

24. Peretz C, Herman T, Hausdorff JM, et al. Assessing fear of falling: can a short version of the Activities-Specific Balance Confidence scale be useful? Mov Disord. 2006;21(12):2101–2105. doi:10.1002/mds.21113

25. Ishige S, Wakui S, Miyazawa Y, et al. Psychometric properties of a short version of the Activities-Specific Balance Confidence scale-Japanese (Short ABC-J) in community-dwelling people with stroke. Physiother Theory Pract;2021;1–14. doi:10.1080/09593985.2021.1888342

26. Freitas RM, Ribeiro KF, Barbosa JS, et al. Validity and reliability of the Brazilian Activities-Specific Balance Confidence scale and determinants of balance confidence in community-dwelling older adults. Physiother Theory Pract. 2020;1:1–10.

27. Jensen J, Lundin-Olsson L, Nyberg L, et al. Falls among frail older people in residential care. Scand J Public Health. 2002;30(1):54–61. doi:10.1177/14034948020300011201

28. Borson S, Scanlan JM, Watanabe J, et al. Improving identification of cognitive impairment in primary care. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21(4):349–355. doi:10.1002/gps.1470

29. Borson S, Scanlan J, Brush M, et al. The mini-cog: a cognitive ‘vital signs’ measure for dementia screening in multi-lingual elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15(11):1021–1027. doi:10.1002/1099-1166(200011)15:11<1021::AID-GPS234>3.0.CO;2-6

30. Borson S, Scanlan JM, Chen P, et al. The Mini-Cog as a screen for dementia: validation in a population-based sample. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(10):1451–1454. doi:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51465.x

31. Berg KO, Wood-Dauphinee SL, Williams JI, et al. Measuring balance in the elderly: validation of an instrument. Can J Public Health. 1992;83(Suppl 2):S7–S11.

32. Zhou M, Peng N, Zhu CX, et al. Predictive Value of Functional Gait Assessment and Berg Balance Scale for Fall in Community-dwelling Older Adults. Chin J Rehabil Theory Pract. 2013;19(01):66–69.

33. Al-Osail AM, Al-Sheikh MH, Al-Osail EM, et al. Is Cronbach’s alpha sufficient for assessing the reliability of the OSCE for an internal medicine course? BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:582. doi:10.1186/s13104-015-1533-x

34. Portney LG, Watkins MP. Foundations of Clinical Research.

35. Mak MK, Lau AL, Law FS, et al. Validation of the Chinese translated Activities-Specific Balance Confidence scale. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(4):496–503. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2007.01.018

36. Ruopp MD, Perkins NJ, Whitcomb BW, et al. Youden Index and optimal cut-point estimated from observations affected by a lower limit of detection. Biom J. 2008;50(3):419–430. doi:10.1002/bimj.200710415

37. Schott N. Reliability and validity of the German short version of the Activities specific Balance Confidence (ABC-D6) scale in older adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;59(2):272–279. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2014.05.003

38. Monjezi S, Negahban H, Tajali S, et al. Psychometric properties of the Persian-version of the Activities-specific Balance Confidence scale and Fall Efficacy Scale-International in Iranian patients with multiple sclerosis. Physiother Theory Pract. 2021;37(8):935–944. doi:10.1080/09593985.2019.1658247

39. Ishige S, Wakui S, Miyazawa Y, et al. Reliability and validity of the Activities-specific Balance Confidence scale-Japanese (ABC-J) in community-dwelling stroke survivors. Phys Ther Res. 2019;23(1):15–22. doi:10.1298/ptr.E9982

40. Schepens S, Goldberg A, Wallace M. The short version of the Activities-Specific Balance Confidence (ABC) scale: its validity, reliability, and relationship to balance impairment and falls in older adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;51(1):9–12. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2009.06.003

41. Hewston P, Deshpande N. The Short Version of the Activities-Specific Balance Confidence Scale for Older Adults with Diabetes-Convergent, Discriminant and Concurrent Validity: a Pilot Study. Can J Diabetes. 2017;41(3):266–272. doi:10.1016/j.jcjd.2016.10.007

42. Fuller K, Omana MH, Frengopoulos C, et al. Reliability, validity, and agreement of the short-form Activities-Specific Balance Confidence Scale in people with lower extremity amputations. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2019;43(6):609–617. doi:10.1177/0309364619875623

43. Franchignoni F, Bavec A, Zupanc U, et al. Validation of the Activities-Specific Balance Confidence Scale With 5-Option Response Format in Slovene Lower-Limb Prosthetic Users. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2021;102(4):619–625. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2020.10.126

44. Haynes RB, Sackett DL, Guyatt GH, et al. Clinical Epidemiology: How to Do Clinical Practice Research.

45. Moiz JA, Bansal V, Noohu MM, et al. Activities-Specific Balance Confidence scale for predicting future falls in Indian older adults. Clin Interv Aging. 2017;12:645–651. doi:10.2147/CIA.S133523

46. An S, Lee Y, Lee D, et al. Discriminative and predictive validity of the short-form activities-specific balance confidence scale for predicting fall of stroke survivors. J Phys Ther Sci. 2017;29(4):716–721. doi:10.1589/jpts.29.716

47. Park SH. Tools for assessing fall risk in the elderly: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2018;30(1):1–16. doi:10.1007/s40520-017-0749-0

48. Herssens N, Swinnen E, Dobbels B, et al. The Relationship Between the Activities-Specific Balance Confidence Scale and Balance Performance, Self-perceived Handicap, and Fall Status in Patients With Peripheral Dizziness or Imbalance. Otol Neurotol. 2021;42(7):1058–1066. doi:10.1097/MAO.0000000000003166

49. Buderer NM. Statistical methodology: i. Incorporating the prevalence of disease into the sample size calculation for sensitivity and specificity. Acad Emerg Med. 1996;3(9):895–900. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.1996.tb03538.x

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.