Back to Journals » Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment » Volume 10

Temperament, character traits, and alexithymia in patients with panic disorder

Authors Izci F, Gültekin BK, Saglam S, Iris Koc M , Zincir SB, Atmaca M

Received 18 February 2014

Accepted for publication 27 March 2014

Published 16 May 2014 Volume 2014:10 Pages 879—885

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S62647

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Filiz Izci,1 Bulent Kadri Gültekin,1 Sema Saglam,2 Merve Iris Koc,1 Selma Bozkurt Zincir,1 Murad Atmaca3

1Department of Psychiatry, Erenkoy Training and Research Hospital for Psychiatry, Istanbul; 2Department of Psychiatry, Adiyaman Training and Research Hospital, Adiyaman, 3Firat University School of Medicine Department of Psychiatry, Elazig, Turkey

Background: The primary aim of the present study was to compare temperament and character traits and levels of alexithymia between patients with panic disorder and healthy controls.

Methods: Sixty patients with panic disorder admitted to the psychiatry clinic at Firat University Hospital were enrolled in the study, along with 62 healthy age-matched and sex-matched controls. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV axis I (SCID-I), Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI), Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20), and Panic Agoraphobia Scale (PAS) were administered to all subjects.

Results: Within the temperament dimension, the mean subscale score for harm avoidance was significantly higher in patients with panic disorder than in controls. With respect to character traits, mean scores for self-directedness and cooperativeness were significantly lower than in healthy controls. Rates of alexithymia were 35% (n=21) and 11.3% (n=7) in patients with panic disorder and healthy controls, respectively. The difficulty identifying feelings subscale score was significantly higher in patients with panic disorder (P=0.03). A moderate positive correlation was identified between PAS and TAS scores (r=0.447, P<0.01). Moderately significant positive correlations were also noted for PAS and TCI subscale scores and scores for novelty seeking, harm avoidance, and self-transcendence.

Conclusion: In our study sample, patients with panic disorder and healthy controls differed in TCI parameters and rate of alexithymia. Larger prospective studies are required to assess for causal associations.

Keywords: panic disorder, temperament, character, personality, alexithymia

Introduction

Panic disorder is characterized by panic attacks.1 Episodes are typically sudden, spontaneous, and accompanied by intense somatic and cognitive symptoms. Panic disorder is also often accompanied by personality disorders, with avoidant, histrionic, and borderline personality disorders being particularly common.2,3 In addition, avoidant personality disorder characteristics are commonly observed in patients with panic disorder with phobic avoidance.4

Cloninger has developed a psychobiological theory to define personality structure and development. In his model, temperament and personality dimensions are two essential cornerstones of personality. The “temperament component” is four-dimensional, consisting of novelty seeking, harm avoidance, reward dependence, and persistence. Meanwhile, the “character component” is three-dimensional, comprised of self-directedness, cooperativeness, and self-transcendence. Temperament dimensions reflect the biological components of personality, which are hereditary. Temperament is distinguished from character by individual differences in interpersonal relationships and object relations. Character dimensions, meanwhile, are molded by life events, culture, and social learning.5–8

Alexithymia is defined as difficulty realizing, identifying, discriminating, and expressing one’s own feelings and the feelings of others.9 There is a positive relationship between the “identifying difficulties and describing feelings” dimension of alexithymia and anxiety symptoms, in that difficulties identifying and describing feelings themselves increase levels of anxiety.10 In one study of patients with panic disorder who showed higher alexithymia levels than controls, there was impairment in feeling and bodily sensations in terms of information processing.11 The study results further suggested that competence in feeling and bodily sensations could be protective in populations at high risk for panic disorder. It was suggested in the literature that, relative to alexithymia, Cloninger’s psychobiological model of personality could predict psychopathological symptoms in a distinct and meaningful manner,12 and a vast majority of alexithymic subjects were also highly anxious, in contrast with the low proportion among nonalexithymic subjects.13

There are few studies in the literature that have examined the relationship between alexithymia and temperament-character traits in patients with panic disorder. In this study, our primary objective was to identify and compare rates of alexithymia and temperament and character traits in patients with panic disorder. Our secondary objective was to compare patients with panic disorder and healthy controls in terms of these psychological parameters.

Patients and methods

Sample

Sixty-seven patients consecutively referred to the outpatient psychiatry clinic at Firat University Hospital were evaluated. Of these, seven either refused to participate in the study or were otherwise ineligible for a variety of reasons, including illiteracy, another accompanying Axis I disorder, a general medical condition that could produce physiological effects indistinguishable from panic disorder, a neurological disease, or either a past or present history of psychoactive substance abuse and/or addiction, leaving 60 patients with panic disorder for final analysis. In addition, 62 healthy age-matched and sex-matched controls who otherwise met the study criteria were recruited. The study was approved by the Firat University Faculty of Medicine ethics committee. A diagnosis of panic disorder was made by an attending psychiatrist in accordance with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) using the Structured Clinical Interview for Axis I Disorders (SCID-I).

Data collection tools

Sociodemographic and clinical information

Sociodemographic and clinical information was collected using a questionnaire consisting of seven questions regarding age, sex, marital status, educational level, and economic status, and for patients with panic disorder, the onset and duration of symptoms.

DSM-IV structured clinical interview for axis I disorders

The SCID-I is a semistructured clinical interview designed to assess for DSM-IV Axis I disorders.14 In the current study, we used the Turkish version, for which satisfactory reliability and validity have been demonstrated by Çorapçioğlu and Aydemir.15

Temperament and character inventory

The Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI) was developed by Cloninger, based on his personality theory. It is a self-rating scale composed of seven subscales encompassing 240 items, all with “right” and “wrong” response options. The seven subscales comprise four temperament subscales (novelty seeking, harm avoidance, reward dependence, and persistence) and three character subscales (self-directedness, cooperativeness, and self-transcendence).6,7 Satisfactory reliability and validity for the Turkish version were confirmed in a study by Köse et al.16

Toronto alexithymia scale

The Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS, also known as the TAS-20) includes 20 questions across three dimensions, ie, difficulty identifying feelings, difficulty describing feelings, and externally oriented thinking.17 People who score 61 or higher are considered to have alexithymia. The TAS has undergone numerous adaptations, with the first translation to Turkish done by Dereboy.18

Panic and agoraphobia scale

The Panic and Agoraphobia Scale (PAS) evaluates panic attack features (three questions, plus one question that is not scored), agoraphobia or avoidance behaviors (three questions), anticipatory anxiety (two questions), disability (three questions), and health concerns (two questions).19 A validity and reliability study for the Turkish version has been published by Tural et al.20

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS version 15.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Student’s t-tests were used for intergroup comparisons of continuous variables, with Pearson’s chi-square tests utilized for categorical variables. Pearson correlation analysis was performed to assess the relationship between continuous variables. For all analyses, α<0.05 was considered significant. However, for all comparisons, a modified Bonferroni correction (α<0.01) was applied to reduce the risk of type I error.

Results

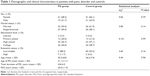

Sixty patients met the DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for panic disorder and were deemed suitable for enrolment, as well as 62 healthy controls matched for age and sex. No statistically or clinically significant differences were noted between cases and controls in terms of sociodemographic characteristics (P>0.05). For the patients, the mean age of onset of panic disorder was 31.13±11.39 years, the mean duration of panic disorder symptoms was 4.87±4.5 years, and the mean PAS score was 20.55±11.83 (Table 1).

Among patients with panic disorder, the fatigability and asthenia harm avoidance subscale score (HA4) was significantly higher than in controls. Conversely, the total self-directedness score and the SD1, SD2, and SD3 (responsibility, purposefulness, resourcefulness) subscale scores were significantly lower in those with panic disorder, as was the social acceptance cooperativeness (C1) subscale score (P<0.01, Table 2).

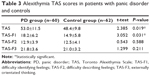

Overall, 33.3% (n=20) of cases and 11.3% (n=7) of controls met the criteria for alexithymia (P=0.003). In addition, the TAS-20 and TAS-F1 (difficulty identifying feelings) scores were significantly higher in the panic disorder group (Table 3).

A moderately strong positive correlation was identified between the PAS and TAS scores. In addition, statistically significant moderately strong positive correlations were evident between PAS scores and the novelty seeking, harm avoidance, and self-transcendence subscale scores of the TCI (P<0.01, Table 4).

Further analysis of the correlations between the TAS and TCI revealed: a positive weak correlation between the TAS and harm avoidance score (r=0.254; P=0.005); a moderate negative correlation between the TAS and self-directedness score (r= −0.481; P<0.001); and a weak negative correlation between the TAS and cooperativeness score (r= −0.321; P<0.001) No statistically significant correlations were detected between the TAS score and any other TCI subscale.

Discussion

In our study, within the temperament dimension, the mean total harm avoidance and fatigability (HA4) subscale scores were significantly higher in patients with panic disorder than in controls. This makes sense, because individuals with high harm avoidance scores are often quite negative in their outlook regarding the potential for future problems; as such, they may exhibit avoidance behaviors, fear of uncertainty, shyness, insecurity, pessimism, anxious personality traits, and anxiety and depressive disorder traits.5,6 Several earlier studies investigating the temperament characteristics of patients with panic disorder have also found these patients to have higher harm avoidance scores than controls.21–26 Additionally, in the literature, high harm avoidance dimension categorical scores have been reported to be associated with cluster C personality disorders.27,28

Within the character dimension, total self-directedness scores, as well as the responsibility (SD1), purposefulness (SD2), and resourcefulness (SD3) subscale scores and the social acceptance (C1) subscale score for cooperativeness were significantly lower in patients with panic disorder. Again, this makes sense, because self-directed individuals tend to be confident, responsible, reliable, and resourceful people who have personal goals and are at peace with themselves.29 Conversely, individuals with low self-directedness scores typically blame others, are usually incompetent, and undisciplined.6,7 Individuals with TCI self-directedness subscale scores lower than 20 are weak in terms of self-directedness and are likely to be diagnosed with a personality disorder. They also find it difficult to take responsibility, choose meaningful goals, accept limitations, and develop discipline habits.30 In our study, the self-directedness total score and the SD1, SD2, and SD3 subscale scores were significantly lower in patients than in controls. Having low scores on the self-directedness scale may be interpreted as failing to control one’s own behavior and manage interpersonal relationships. As such, personality disorders may coexist.

People with high levels of cooperativeness perceive themselves as part of society. Consequently, they are identified as people who are capable of empathizing with and understanding others and, as such, are compassionate, supportive, and principled. Conversely, individuals with low levels of cooperativeness tend to pay attention only to themselves, and are intolerant and critical of others as well as being opportunistic.5,8 In our study, cooperativeness scores were significantly lower in patients with panic disorder than in controls. Having low scores on the cooperativeness scale may be interpreted as engaging more with self, being intolerant of others, and having a desire to live apart from society. Cloninger et al reported that low self-directedness and cooperativeness subscale scores may predict the development of a personality disorder.6

Alexithymia is a recently coined term in clinical practice. It is defined as difficulty realizing, recognizing, discriminating, and expressing feelings.31 According to Taylor,17 alexithymia is not a disease; rather, it is a condition related to personality. However, sociocultural factors are also influential in the development of alexithymia. According to Pennebaker,32 alexithymic traits are linked to self-reflection skills and emotional inhibition. Because of deficiencies in processing emotions during cognitive processes, the individual focuses on physical elements of emotional stimulation. This condition is consistent with the somatic complaints often observed in alexithymic patients. Paez et al33 suggested that alexithymia, as a personal tendency and coping style, has four components that include deficiencies in thinking and communicating about emotions, dissociation between emotional and physical reactions, and a conflict between a tendency to give away secrets and to suppress this tendency.

Investigators examining the relationship between anxiety and alexithymia have reported that alexithymia is primarily associated with deficient recognition and identification of emotions.10,34 Consistent with these findings, Motan and Gencoz34 highlighted a positive relationship between difficulties within the “recognizing and identifying feelings” dimension of the TAS-20 and anxiety symptoms. In addition, in this study, an inverse relationship was observed between difficulties communicating feelings and anxiety symptoms. Accordingly, in this study, we observed that as anxiety symptoms increased, difficulties expressing feelings decreased. In the opposite case, people who have difficulty expressing feelings avoid these types of relationship due to their coping mechanisms, so can reduce their anxiety levels. In another study, anxiety and panic symptoms and verbal cognitive skills were found to be associated with alexithymia; and the comorbidity of alexithymia in patients with panic disorder was found to adversely affect verbal cognitive function.35

In a study using the TAS-20 to assess for the presence of alexithymia in panic disorder, the prevalence of alexithymia was found to be 39%.36 In another study performed using the TAS-20, the prevalence of alexithymia was 34%.37 In a third follow-up study in which 52 adult patients diagnosed with panic disorder were enrolled, the prevalence of alexithymia was 44.2%.38 In our study, in which we used the TAS-20, 33% of our patients with panic disorder and 11.3% of our controls were alexithymic. TAS-20 and TAS-F1 scores were significantly higher in patients with panic disorder. One study has suggested that there is impairment in emotional and bodily sensation information processing in subjects with panic disorder, and emotional and bodily sensation competencies could be protective factors for panic disorder in high-risk populations.11 Findings from another study indicated that, because alexithymic patients are unable to identify, differentiate, and articulate their emotions, they make less use of individualized psychotherapy, and there is some tendency for alexithymic patients to prefer group therapy instead of individual psychotherapy.39

Accordingly, we suggest that patients with panic disorder are more alexithymic, may have more difficulty identifying feelings than others, and want to make less use of individualized psychotherapy. Finally, total alexithymia scores and panic agoraphobia scale scores were positively correlated in our sample, ie, agoraphobic avoidance increases with increasing alexithymia scores. On correlation analysis assessing the relationship between panic agoraphobia scale scores and temperament and character subscores, there was a positive relationship with novelty seeking, harm avoidance, and self-transcendence scores. Accordingly, it can be said that agoraphobic avoidance should be expected to be present more often in alexithymic, impulsive, and anxious individuals. In a study examining the relationship between alexithymia and temperament-character traits, the regression analysis identified low self-directedness, low reward dependence, and to a minor degree harm avoidance dimensions of TCI as independent predictors for alexithymia.40 In our study, on correlation analysis of TAS and TCI scores, a positive correlation was observed between TAS and harm avoidance, but a negative correlation between TAS and self-directedness and cooperativeness scores by correlation analysis of TAS and TCI scores. In another study in male alcohol-dependent inpatients suffering from intense anxiety symptoms, TAS-20 scores correlated positively with harm avoidance and self-transcendence and negatively with self-directedness and cooperativeness.41 In another study, it was seen that alexithymia was correlated with depression and that TAS-20 total and subscale scores were correlated with harm avoidance, low self-directedness, low cooperativeness, and low reward dependence scores.42,43 Low self-directedness and cooperativeness scores that predict personality pathology may suggest an association with alexithymia and personality disorders.4–7 Likewise, it may be argued that alexithymic individuals are likely to have higher harm avoidance scores.

Our study has several limitations, including its cross-sectional design that precludes any determination of causality between variables, the relatively small subject samples that limit power and generalizability, and the exclusive use of self-report questionnaires. Despite these limitations, we feel that our study has merit as a precursor analysis in which personality dimensions and alexithymic traits are evaluated together for the first time.

In conclusion, in this study comparing 60 adults with panic disorder and 62 age-matched and sex-matched controls, intergroup differences were evident both in temperament and character inventory scores, and in rates and scores for alexithymia. It is noteworthy that harm avoidance was greater among patients with panic disorder, while self-directedness and cooperativeness was lower. Greater harm avoidance seen in patients with panic disorder may suggest a chronic course, while lower self-directedness and cooperativeness may suggest a higher risk of concomitant alexithymia and personality disorder. In addition, the presence of alexithymia in these patients might predict agoraphobic avoidance, fear, worrying, and anxiety. This being said, controlled and long-term prospective studies with larger sample sizes are needed to more definitively investigate the relationships between these various constructs.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington DC, USA: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. | ||

Sciuto G, Diaferia G, Battaglia M, Perna G, Gabriele A, Bellodi L. DSM-III-R personality disorders in panic and obsessive-compulsive disorder: a comparison study. Compr Psychiatry. 1991;32:450–457. | ||

Mavissakalian M, Hamann MS, Jones B. A comparison of DSM-III personality disorders in panic/agoraphobia and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 1990;31:238–244. | ||

Reich J, Noyes R Jr, Troughton E. Dependent personality disorder associated with phobic avoidance in patients with panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144:323–326. | ||

Cloninger CR. A systematic method for clinical description and classification of personality variants: a proposal. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:573–588. | ||

Cloninger CR, Svrakic DM, Przybeck TR. A psychobiological model of temperament and character. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:975–990. | ||

Cloninger CR, Przybeck TR, Svrakic DM, Wetzel RD. The Temperament and Character Inventory: A Guide to its Development and Use. Washington, DC, USA: Center for Psychobiology of Personality, Department of Psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine; 1994. | ||

Köse S. [A psychobiological model of temperament and character: TCI]. Yeni Symposium Dergisi. 2003;41:86–97. | ||

Sifneos PE. Alexithymia and its relationship to hemispheric specialization, affect, and creativity. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1988;11:287–293. | ||

Devine H, Stewart SH, Watt MC. Relations between anxiety sensitivity and dimensions of alexithymia in a young adult sample. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47:145–158. | ||

Cucchi M, Cavadini D, Bottelli V, et al. Alexithymia and anxiety sensitivity in populations at high risk for panic disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2012;53:868–874. | ||

Conrad R, Wegener I, Imbierowicz K, Liedtke R, Geiser F. Alexithymia, temperament and character as predictors of psychopathology in patients with major depression. Psychiatry Res. 2009;165:137–144. | ||

Karukivi M, Hautala L, Kaleva O, et al. Alexithymia is associated with anxiety among adolescents. J Affect Disord. 2010;125:383–387. | ||

First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I), Clinical Version. Washington DC, USA: American Psychiatric Press Inc; 1997. | ||

Çorapçioğlu A, Aydemir Ö, Yildiz M. DSM-IV Eksen I Bozukluklari Için Yapilandirilmiş Klinik Görüşme Kullanim Kilavuzu (SCID-I). [Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, Clinical Version.] Ankara, Turkey: Hekimler Yayin Birliği; 1999. | ||

Köse S, Sayar K, Ak I. Mizaç ve Karakter Envanteri (Türkçe TCI): geçerlik, güvenirliği ve faktör yapisi. [Turkish version of the Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI):reliability, validity, and factorial structure.] Klinik Psikofarmakoloji Bülteni. 2004;14:107–131. | ||

Taylor GJ, Bagby RM, Parker JDA. The revised Toronto Alexithymia Scale: some reliability, validity, and normative data. Psychother Psychosom. 1992;57:34–41. | ||

Dereboy IF. Aleksitimi: bir gözden geçirme. [Alexithymia: A review.] Türk Psikiyatri Dergisi. 1990;1:157–165. | ||

Bandelow B. Assessing the efficacy of treatments for panic disorder and agoraphobia. II. The Panic and Agoraphobia Scale. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1995;10:73–81. | ||

Tural Ü, Fidaner H, Alkin T. Panik ve Agorafobi Ölçeğinin güvenirlik ve geçerliği. [Validity and Reliability of the Turkish Version of the Panic and Agoraphobia Scale.] Türk Psikiyatri Dergisi. 2000;11:29–39. | ||

Saviotti FM, Grandi S, Savron G. Characterological traits of recovered patients with panic disorder and agoraphobia. J Affect Disord. 1991;23:113–117. | ||

Ampollini P, Marchesi C, Signifredi R. Temperament and personality features in panic disorder with or without comorbid mood disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1997;95:420–423. | ||

Battaglia M, Bertella S, Bajo S. An investigation of the co-occurrence of panic and somatization disorders through temperamental variables. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:726–729. | ||

Ampollini P, Marchesi C, Signifredi R. Temperament and personality features in patients with major depression, panic disorder and mixed conditions. J Affect Disord. 1999;52:203–207. | ||

Kennedy BL, Schwab JJ, Hyde JA. Defense styles and personality dimensions of research subjects with anxiety and depressive disorders. Psychiatr Q. 2001;72:251–262. | ||

Wiborg IM, Falkum E, Dahl AA. Is harm avoidance an essential feature of patients with panic disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2005;46:311–314. | ||

Brown SL, Svrakic DM, Przybeck TR. The relationship of personality to mood and anxiety states: a dimensional approach. Psychiatry Res. 1992;26:192–211. | ||

Svrakic DM, Whitehead C, Przybeck TR, Cloninger CR. Differential diagnosis of personality disorders by the seven-factor model of temperament and character. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:991–999. | ||

Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Kaplan and Sadock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005:869–870. 82. | ||

Cloninger CR. A unified biosocial theory of personality and its role in the development of anxiety states. Psychiatr Dev. 1986;3:167–226. | ||

Koçak R. Aleksitimi: Kuramsal çerçeve, tedavi yaklaşimlari ve ilgili araştirmalar. [Theoretical framework therapeutic approaches and related researches.] Ankara Üniversitesi Eğitim Bilimleri Fakültesi Dergisi. 2002;35:183–212. | ||

Pennebaker JW. Confession, inhibition and disease. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 1989;22:211–244. | ||

Paez D, Basebe N, Voldoseda M. Confrontation: inhibition, alexithymia and health. In: Pennebaker JW, editor. Emotion, Disclosure and Health. 2nd ed. Washington, DC, USA: American Psychological Association; 1977. | ||

Motan I, Gençöz T. [Aleksitimi boyutlarinin depresyon ve anksiyete belirtileri ile ilişkileri]. Türk Psikiyatri Dergisi. 2007;18:333–343. | ||

Galderisi S, Mancuso F, Mucci A, Garramone S, Zamboli R, Maj M. Alexithymia and cognitive dysfunctions in patients with panic disorder. Psychother Psychosom. 2008;77:182–188. | ||

Iancu I, Dannon PN, Poreh A, Lepkifker E, Grunhaus L. Alexithymia and suicidality in panic disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2001;42:477–481. | ||

Cox BJ, Swinson RP, Shulman ID, Bourdeau D. Alexithymia in panic disorder and social phobia. Compr Psychiatry. 1995;36:195–198. | ||

Marchesi C, Fontò S, Balista C, Cimmino C, Maggini C. Relationship between alexithymia and panic disorder: a longitudinal study to answer an open question. Psychother Psychosom. 2005;74:56–60. | ||

Ogrodniczuk JS, Piper WE, Joyce AS. Effect of alexithymia on the process and outcome of psychotherapy: a programmatic review. Psychiatry Res. 2011;190:43–48. | ||

Grabe HJ, Spitzer C, Freyberger HJ. Alexithymia and the temperament and character model of personality. Psychother Psychosom. 2001;70:261–267. | ||

Evren C, Kose S, Sayar K, et al. Alexithymia and temperament and character model of personality in alcohol-dependent Turkish men. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;62:371–378. | ||

Picardi A, Toni A, Caroppo E. Stability of alexithymia and its relationships with the ‘big five’ factors, temperament, character, and attachment style. Psychother Psychosom. 2005;74:371–378. | ||

Celikel FC, Kose S, Erkorkmaz U, Sayar K, Elbozan Cumurcu B, Cloninger CR. Alexithymia and temperament and character model of personality in patients with major depressive disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2010;51:64–70. |

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.