Back to Journals » Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare » Volume 11

Reablement teams’ roles: a qualitative study of interdisciplinary teams’ experiences

Authors Hjelle KM, Skutle O, Alvsvåg H, Førland O

Received 21 December 2017

Accepted for publication 8 May 2018

Published 3 July 2018 Volume 2018:11 Pages 305—316

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S160480

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Kari Margrete Hjelle,1,3 Olbjørg Skutle,2,3 Herdis Alvsvåg,4 Oddvar Førland3,4

1Department of Health and Functioning, Faculty of Health and Social Sciences, Western Norway University of Applied Sciences, Bergen, Norway; 2Department of Welfare and Participation, Faculty of Health and Social Sciences, Western Norway University of Applied Sciences, Bergen, Norway; 3Centre for Care Research Western Norway, Bergen, Western Norway University of Applied Sciences, Bergen, Norway; 4Faculty of Health Sciences, VID Specialized University, Bergen Campus, Bergen, Norway

Introduction: Reablement is a service for home-dwelling older people experiencing a decline in health and function. The focus of reablement is the improvement of the person’s function and coping of his or he valued daily activities. The health care professionals and the home care personnel are working together with the older person toward his goals. In reablement, health care personnel are organized in an interdisciplinary team and collaborate with the older person in achieving his goals. This organizing changes the roles of home care personnel from working almost alone to collaborating with different health care professionals. There is little scientific knowledge describing the roles of different health care professionals and home care personnel in the context of reablement. This study’s objective is to explore and describe the roles of interdisciplinary teams in reablement services in a Norwegian setting.

Method: Two interdisciplinary teams consisting of 17 health care professionals (i.e. occupational therapists, physiotherapists, nurses, and social educators) and ten home care personnel (auxiliary nurses and nursing assistants) participated in three focus group discussions. In addition, three interviews were conducted with occupational therapists, physiotherapists, nurses, and auxiliary nurses. The focus group discussions and the interviews were all digitally recorded, transcribed verbatim and analyzed using the qualitative content analysis.

Results: The health care professionals’ main role was to be consultants and advisors, consisting of (1) planning, adjusting, and conducting follow-ups of the intervention; (2) delegating tasks; and (3) supervising the home care personnel. The home care personnel’s main role was to be personal trainers, consisting of (1) encouraging and counseling the older adults to perform everyday activities; and (2) conveying a sense of security while they performed everyday activities. The role of interdisciplinary collaboration was a common role for both the health care professionals and the home care personnel.

Conclusion: The health care professionals established the setting, and had the main roles of supervision, delegating tasks, and main responsibility for the intervention. The home care personnel accepted the delegations and had a main role as personal trainers. Their work changed from body care to encouraging and counseling the older person to perform activities themselves in a safe way. The health care professionals and the home care personnel collaborated closely across roles. The home care personnel experienced a shift in role from home care to a person-centered care. This was perceived as strengthening the health care identity of their role.

Keywords: reablement, interdisciplinary team work, collaboration, roles, care work

Introduction

In many countries around the world, new reforms aiming to promote independence, self-determination, and self-care of older persons, and thus home care rehabilitation are actualized.1,2 With these reforms, the older person is reconstructed as more resourceful and possessing more potential than previously anticipated, providing a new and optimistic framing of home care for older adults.3

Reablement service is one new reform and has been implemented in countries like UK, US, Australia, and New Zealand since year 2000.4 Also Denmark, Sweden, and Norway have implemented reablement service.5–7 The service is for home-dwelling older adults experiencing a decline in health and function. The main purpose of reablement is the improvement of the person’s function and coping of valued meaningful activities in everyday life.8–10

The home care personnel and health care professionals are reorganized from multiple individual health care personnel into an interdisciplinary team.7,11–13 The team is emphasizing the older person’s practicing and coping, valued and meaningful activities and participating in society.8,14 Thus, the reablement intervention is tailored to the older person’s goals. Accordingly, the components of the rehabilitation plan vary, as described in Table 1.7

| Table 1 Features of the reablement intervention Notes: Reproduced from Tuntland H, Espehaug B, Forland O, Hole AD, Kjerstad, E, Kjeken I. Reablement in community-dwelling adults: study protocol for a randomized control trial. BMC Geriatric. 2014;14:139.14 Abbreviation: COPM, Canadian Occupational Performance Measure. |

A systematic review of Pettersson and Iwarsson, covering the period 2000–2014,15 found that scientific studies of reablement describing or investigating the effects of reablement for older community-living people, is limited. However, there are several indications of positive effects on primary outcomes such as remaining living at home, improved independence in activities of daily living, and improved physical activity. They conclude that more research is needed to strengthen the evidence base regarding reablement service.

A systematic review by Tessier et al12 concludes that there is good evidence supporting the effectiveness of reablement, particularly regarding health-related quality of life (HRQoL), costs, and service utilization. Fewer people require home care services after receiving reablement compared to those receiving usual home care services. However, though evidence was limited for maintaining the effects in the long term, it was suggested that the benefits of reablement had an effect on visits to the emergency department, risk of residential care placement, and mortality. Although reablement has the potential to be cost-effective, this is difficult to quantify considering the wide range of costs reported in the literature. However, Kjerstad and Tuntland4 found that reablement is a more cost-effective intervention compared with usual care. The assessments of performance and satisfaction regarding daily activities were significantly higher in the reablement group compared with the control group and this was achieved at lower cost. In addition, in the post-trial period, the intervention group requested significantly fewer home visits which were, on average, of shorter duration compared with the control group.

In a systematic review by Sims-Gould et al9 the impact of reablement, reactivation, rehabilitation, and restorative (4H) programs for older adults in receipt of home care services, were reviewed. These interventions show some promising outcomes in the home care context. They highlight the collaborative goal setting and the personalized support plans. Persons participating in a 4H program had greater improvement in their self-care, home management and mobility scores than older persons receiving the usual home care at discharge.

In the qualitative study by Birkeland et al,10 the interdisciplinary team is characterized by interactive tasks, and implies high levels of communication, mutual planning, shared responsibilities, and decisions. In this collaboration it is important to trust one another, and have respect for each other’s knowledge and roles in the team.10 The study by Birkeland et al10 illustrated that exchange of knowledge depends on each health care personnel in the reablement team being conscious of their own role and special competence. From working almost alone within one’s own discipline to extensive collaboration across professions, is a great change in roles for all health care personnel in the reablement team. This implies that team members must be willing to take on a broader range of tasks than when working independently.

In a qualitative study by Hjelle et al,7 the results highlighted the importance of reablement team members’ positive attitudes toward one another, sharing knowledge and learning from each other. Moe and Brataas16 and Pellat17 also argue that health care professionals and home care personnel need to develop supportive structures that enable greater communication and understanding of each other’s roles and competencies. The roles of occupational therapists and home care personnel in reablement teams were explicitly described in the study of Winkel et al.18 The role of the occupational therapist was to specify activities of daily living (ADL), convey the relevant task performance problems to the patient, set goals together with the patient and the home care personnel, and plan and adjust interventions during the program. The role of the home care personnel was to support the patient in their active engagement in performing tasks and, at the same time, perform those parts of the ADL that were too difficult for the patient. The occupational therapist acted as a case manager and as a supervisor for the home care personnel in the reablement service.

Earlier research has highlighted that the transition from doing tasks for the older person to making it possible for them to perform most of the tasks themselves is a challenge to health care personnel.8,19 In Norway, Liaaen20 found that role conflicts may occur when care personnel change their way of working. The health care professionals have roles as supervisors for health care personnel to encourage the older adult to practice and cope with the everyday activities themselves. In resolving this dilemma between doing activities for the older person and facilitating his self-activity, negotiations between these two roles were necessary. This is in line with Meldgaard Hansen5 and Meldgaard Hansen and Kamp,21 who argues that this way of working, especially for home care personnel, changes from body care and doing activities for the older person, to supporting and supervising the person as he performs the primary and instrumental activities of daily living. The supporting and supervising role also changes the career-patient role especially for home care personnel, who change from a passive to an active person-centered role.15 Accordingly, in interdisciplinary reablement, the team members sometimes must learn to give up roles or activities they would otherwise perform themselves. Pettersson and Iwarsson15 highlight that the specific roles of various professional and staff groups are often insufficiently described, as are the interventions as such, and there is a lack of attention to person-centered aspects such as the meaningfulness of the specific activities.

As the review above shows, empirical studies on the roles of interdisciplinary teams in reablement are sparse, and some important gaps remain. There is a gap in research describing the roles of health care professionals and the home care personnel in the context of the reablement team. Thus, the aim of the study is to explore and describe the roles of the interdisciplinary team in the reablement service in Norway.

Method

Design

This study used a qualitative approach drawing on hermeneutic and phenomenological methods. These approaches are valuable to gather data from the people concerned, such as the reablement team, and how the members experience participation in the new service.22,23 The research method was focus group discussions and interviews to gather in-depth descriptions of the participants’ experiences. Combining focus group discussion with interviews, including open-ended or structured questions, gives the researchers and the team members the opportunity to further explore themes or issues identified in the focus group discussions.24,25 The study received ethical approval from the Norwegian Social Science Data Service (project number 47026). Participation in the study was voluntary, and written informed consent was obtained prior to the focus group and the interviews.

Reablement intervention

The reablement service lasted for a maximum of 3 months for each older adult in the rural community. In the city the reablement service lasted for 4 weeks. The intervention was tailored to the older person’s goals, and thus the components of the rehabilitation plan varied, as described in Table 1.

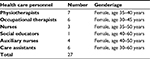

Health care personnel in the interdisciplinary teams consisted of various health care professionals and home care personnel. Health care professionals with a bachelor’s degree included occupational therapists, physiotherapists, nurses, and social educators. Home care personnel without a bachelor’s degree included auxiliary nurses and caring assistants (see Table 2).

| Table 2 Reablement team – Health care personnel are organized into two groups; health care professionals and home care personnel |

Participants and data collection method

Focus group discussion

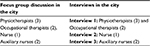

Health care personnel in the interdisciplinary teams participated in three focus group discussions. All the team members in the rural community and in the city (see Table 3) were invited and participated in the focus group discussions. Thus, the sample size was determined by the size of the teams, and altogether 27 health care personnel participated in the focus group discussions. Two focus group discussions were conducted in a rural community with approximately 15,000 inhabitants, and one focus group discussion was conducted in a city with approximately 300,000 inhabitants.

| Table 3 Main characteristic of the participants taking part in the focus group discussions and the interviews |

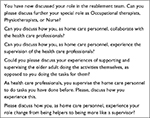

Interviews

In addition, three interviews were conducted in the city with three subgroups: 1) two occupational therapists and three physiotherapists; 2) one nurse; and 3) two auxiliary nurses (see Table 4). These interviews were conducted by three of the authors; KMH, OF, and OS in different rooms after the focus group discussion was finished. The participants in the interviews had also participated in the focus group discussion. The interviews were an opportunity to further outline issues discussed in the focus group. Health care professionals and home care personnel had the opportunity to express their thoughts openly without being influenced by the others. The interviews were also an opportunity to validate and deepen the data already gained and to elaborate further on the participants’ reflections on the topic of the study.

| Table 4 Data collection method |

The local project leader of the reablement service recruited the participants. All the participants in the reablement team in the city and in the rural community were invited and took part in the focus group discussions and the interviews. The inclusion criteria was that the participant had experience from working in the reablement service. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants participating in the data collection method.

The interview guides

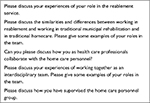

All the interview guides were prepared in advance for the focus group discussions and the interviews (see Boxes 1–4). However, new questions were elaborated according to themes coming up in the process of the focus group discussions. The co-moderator of the focus group discussion took notice of particularly interesting topics for further exploration in the interviews. Four editions of a semi-structured interview guide were developed, two for the focus group discussion in the rural community, one for the focus group discussion and one for the interviews in the city (see Boxes 1–4). The focus group discussion focused on how the health care professionals and home care personnel experienced their role in reablement. To initiate the discussion the moderator of the focus group started with general questions such as: “Please, describe and discuss your experiences of the differences and similarities of working in reablement and ordinary rehabilitation. Please, describe your roles in the reablement service.”

| Box 1 Topics included in the focus group discussion with interdisciplinary teams in the city. |

| Box 2 Topics included in the interview in the city. |

| Box 3 Topics included in the interview guide of the focus group discussion of the health care professionals in the community. |

| Box 4 Topics included in the interview guide of the focus group discussion of the home care personnel in the community. |

The first author (KMH) of this paper conducted the focus group discussion in the rural community, assisted by the second (OS) and third (HA) authors. The fourth author (OF) conducted the focus group discussion in the city, however, the first (KMH) and second (OS) authors, also asked questions to further explore interesting experiences of the participants. The first author (KMH) wrote notes during the session. The focus group discussions lasted between 1 and 2 hours, were digitally recorded and later transcribed verbatim. Once all the interviews were transcribed verbatim, all the transcriptions were analyzed as a whole by all the researchers of this paper.

Data analysis

The interviews were analyzed according to phenomenological de-contextualization and recontextualization.22,23,26 The authors analyzed the transcribed data separately, however, all the steps in the data analysis were discussed together to reach a consensus of the data to support the trustworthiness of the analysis. The analysis followed a four-step analysis procedure.22,26,27 First, the transcripts were read and listen to many times to get an overall view of the data. We moved back and forth across all interviews looking for preliminary and emerging themes that could reflect several of the health care professionals’ and home care personnel’s experiences of participating in the reablement service. Next, we searched for meaning units, reflecting the participants’ experiences of participating in reablement. Then, we began coding by identifying and sorting meaning units. These codings are all text fragments from the data. In this step, we examined the existing codes and added new ones with the researchers moving back and forth between the data and the codes. For example, codes such as “the role of delegating tasks,” “the role as supervisor,” and “the role of collaboration” emerged. During this de-contextualization phase, we reflected on the similarities and differences of each code. The final codes were based on continuous discussions by all the researchers until consensus was reached. The third step of the analysis involved the systematic abstraction of meaning units within each of the code groups that were established in the second step of the analysis. The transcripts were read systematically to identify and classify the meaning units into thematic code groups.

Finally, in the fourth step of the analysis, we developed descriptions and provided stories that reflected the wholeness of the original context. This was outlined in core themes and subthemes, and in this way the data were re-contextualized. To substantiate the core themes and subthemes, representative text elements from the transcripts are included as quotations in the reporting of the results. The research group decided to outline the core themes of each group in order to describe the different groups’ experiences of their roles more clearly and directly.

Results

We found that the roles within the health care professionals were quite different from the roles of home care personnel. The results of the analyses are presented as three main themes as:

- The health care professionals group’s main role was to be consultants and advisors, consisting of: i) planning, adjusting, and conducting follow-ups to the intervention; ii) delegating tasks to the home care personnel; and iii) supervising the home care personnel.

- The home care personnel group’s main role was to be personal trainers, consisting of: i) encouraging and supporting the older adults to perform everyday activities; and ii) conveying a sense of security when older adults performed everyday activities.

- The role of interdisciplinary collaboration was a common role for both the health care professionals and the home care personnel.

The role of consultants and advisors

The health care professionals had the professional responsibility, and thus the role of consultants was more highlighted rather than the role of professionals who treat older adults. The following sections describe the main tasks in the consultant role.

Planning, adjusting, and conducting follow-ups of the interventions

When a decision was made that the home care personnel could conduct simple exercises on their own, it was made during weekly or daily follow-ups by a health care professional. It was expressed as such:

Every week, we make a home visit to older persons to have regular contact with them, assess their development, and hold a conversation around the topic of “what are we doing now?” Then, we also get an idea of whether the quality of the exercises is good enough. We want to see it. We have a collaborative meeting and discuss the person’s activity and create a plan. However, we put a minus sign on what they should not do.

While assessing whether the older person is confident enough to use the stairs, the health care professional always worked in cooperation with the home care personnel. They discussed almost daily about the older person’s situation and progression in reablement. One of the health care professionals said, “Of course, I have the main responsibility for the older person’s training, and I have to be sure it’s safe for him to walk alone on the stairs.”

Delegating tasks to the home care personnel

Health care professionals are responsible for carrying out the reablement service. However, they delegate the routine or day-to day tasks to the home care personnel, as illustrated by the following example:

As a physiotherapist, I can delegate practicing crutch walking with the older person to the home care personnel, given that I have seen that the older person can do it safely and that the home care personnel are competent.

The health care professionals performed mapping and assessments of the older person, initiated intervention, and observed home care personnel practicing with the older person. When the home care personnel performed the training in a proper manner, it indicated that they could continue with the training on their own in an established and safe way. The physiotherapist highlighted: “Then it’s perfectly good that another can do it. I really want to say that. Yes, because I think we give opportunities for more crowd training.” Thus, the health care professionals have the opportunity to use their professional skills together with other older people who need it. This was exemplified by the following quote:

When we have started to teach the older person to use crutches well, and they need to be safe using them, or we have adapted the activity of showering, and the older person needs to be safe in the shower, then the home care personnel can practice further with the older person, and we can move on to other older adults who need our professional expertise.

The occupational therapist said:

My competence is important in the beginning of the rehabilitation, however, I think the home care personnel manage to continue the work that has been started. The home care personnel are very good at supporting and challenging the older persons.

The health care professionals found that delegating responsibility to the home care personnel led to expanded knowledge of the roles of the others in the team. It was expressed in this way: “We have more knowledge of each other’s roles. I do not think we steal knowledge from each other, however, we will be better in our professional practice.”

When delegating tasks, the health care professionals have a special responsibility to not develop the home care personnel into “quasi-therapists.” The professionals have the knowledge that is necessary to analyze the opportunities and limitations of an activity. For example, an older person with hip problems may have restricted movement, and the physiotherapist’s knowledge is necessary to assess and organize movement proposals and daily activities. The home care personnel expressed this about their responsibility when receiving delegated tasks: “All of us write a report from the daily training. If there are any questions, we will contact the professionals quite soon. It is very easy to phone them or meet them at the office, which is very important and reassuring for us.” However, there are situations where the health care professionals did not leave the training to the home care personnel, as expressed in this quote:

When we meet older persons with a newly operated hip who are increasingly coming home earlier and earlier from hospital, it is necessary to have a physiotherapist’s knowledge and experience of how to perform exercises. In similar situations, one must have close therapy and follow-ups from the physiotherapist in the start, and eventually the home care personnel can take over more and more. But if the home care personnel say there is an increasing pain problem, then the physiotherapist quickly returns and assesses the situation.

The physiotherapist highlights that there is a balance of responsibility, as this quote illustrates:

Physiotherapists perform analyses of motion. To some extent, we can teach the home care personnel what to look for in general. But, it is clear that if pain problems arise, physiotherapists need to make a deeper movement analysis of the older person’s walking. So, we must constantly have this balance of responsibility in reablement.

Supervising the home care personnel

The health care professionals supervise the home care personnel in how older adults can perform valued daily activities themselves, and if necessary with assistance. Daily meeting points for the health care professionals give opportunities for formal and informal supervising. It was expressed like this:

It is very often supervising, roughly on a daily basis. And the home care personnel are clever to share experiences with all members of the team. It is important that the supervising is spontaneous, it is not enough to say that Wednesday after 14:00 you are welcome to ask questions. Supervising must be immediate.

Here is another example of how the physiotherapists supervise the home care personnel:

An older person was coming home after staying in a rehabilitation institution. We designed a training program; walking ten minutes each day, and that was realistic for the home care personnel to follow up. Both the person himself and the home care personnel had to take responsibility. They wrote reports and gave feedback to the professionals. Now the older person moves with a walker. Home-based nursing is still there a lot, but the older person has started to make coffee and breakfast himself. Home-based nursing is reduced from 40 to 11 hours a week.

In the focus group discussions the participants discussed how the health care professionals have to state the reasons for their assessments and intervention when they guide the home care personnel. A physiotherapist said: “I often supervise and have discussion with the home care personnel, and then I have to state the reasons for interventions to be exercised by other health care professionals than myself”.

The role of personal trainer

The role of home care personnel as personal trainers is to support the older person in performing daily training according to their own rehabilitation goals. Personal trainers discuss the rehabilitation plan with the health care professionals and what specific body function or daily activities the older person themselves are exercising or performing. The personal trainer writes reports after each training session for further discussion with the health care professionals. The role of the personal trainer includes 1) encouraging and motivating the older adults to perform activities themselves; and 2) conveying a sense of security when performing activities.

Encouraging and motivating the older adults to perform activities themselves

The personal trainers executed the training that the health care professionals recommended for the older person. The trainers had been offered courses on how to encourage and motivate older persons to perform valued activities themselves. This changed their communication style to enable them to capture what was important and motivate the older persons. One personal trainer explained:

It was a man who basically set several goals. Pretty soon, I realized that he was not really motivated for these things. Then you stop and try to motivate for training, so I discussed with him and asked: “what is really important to you?”

Another personal trainer said it like this:

What makes reablement different and interesting is that the older person themselves choose the activities they want to perform themselves. That’s what makes progress. We look for the older person’s motivation throughout the rehabilitation process, we try to find their driving forces.

Personal trainers expressed that they previously had a lot of responsibility, however, they were often alone with the responsibility. In reablement, they had the team’s support and were offered advice and guidance in their executive training role. One personal trainer highlighted this: “Here, you have many health care professionals to support you, so you can be sure of what you do because you always have the expertise around you.”

Conveying a sense of security when performing activities

When the personal trainers described some of their important tasks in collaboration with the older person, words like “to make them feel safe and support them” are used. One of the personal trainers said: “To make sure that this is fine, we repeat exercises and support them in their confidence in coping with the exercises. And then we let go more and more. Yes, there is very much uncertainty.” The personal trainers felt competent in their role because they had support and supervision from the health care professionals. And they repeated the exercises many times. They acquired knowledge of what worked and did not work for the older person. A personal trainer said: “It is so important to have balance between support and challenge, it has a big impact on the results when you push in the right way and in right time.”

After a functional decline, older people may be in need of security and supportive encouragement in the reablement process. For example, someone has to be present when an older person moves from the chair to the bed. One personal trainer said:

We practiced a lot with a stroke patient to cope with going to bed in a comfortable way. Then the patient told the home trainer: “Now I will try, because I’ve been practicing this, but only if you stand there and support me and help me if I cannot handle it.” She practiced several evenings, become more and more confident. She took the responsibility herself when she was ready for it.

In reablement, the same health care professionals and personal trainers practice together with the older person. This conveys security for the person. One of the personal trainers expressed this:

The same home trainers are coming home. They trust you, and they know who you are. We see the development day by day. We arrive precisely, and all this make sense of security because there are a lot of psychological issues people are struggling with, as fear and anxiety. They are very concerned about us. They say very often that they need someone to chat with.

The role of interdisciplinary collaboration

The participants in our study, highlighted that reablement teams are working teams, or working communities. The health care professionals praised the interdisciplinary cooperation because it offered them a unique opportunity to work together toward an older person’s goals, as shown by the following remark:

It is ideal to have interdisciplinary cooperation because we have this collaborative dialogue in the older person’s home. Otherwise, we often have discussions in an office, and we lose the key point that the person concerned is not actually present. We and the home trainers are together with the older persons themselves and listen to what are important activities for them. It gives us a unique opportunity to actually work toward the goals the older person has chosen, and to work in an interdisciplinary way because we all have the same information.

Collaboration across roles strengthen their own professional identity and expands their professional competence. A physiotherapist stated the following:

You can choose to strengthen yourself as a health care professional and gain all the extra aspects from the others. So, as a physiotherapist, I am much stronger now than when I started reablement. I am strong in my profession and allowed to supplement knowledge from the others.

Here is another statement from a personal trainer illustrating the collaborative work:

“I look forward to work every day because we are making a difference. Working closely in a team with different health care professionals is amazing. We have confidence in each other. I feel safe because I know I can ask questions at any time.” The formal and informal exchange of information and discussion of the interdisciplinary team is perceived as a special professional security for the personal trainers. One of them said: “Now we have a meeting place for discussion with the professionals, which we did not have before. We can quickly contact them to discuss issues. It’s a system to exchange and discuss information in the reablement team.”

Personal factors, such as humility and respect for each other’s knowledge and roles, influence the different roles in the interdisciplinary team. In this way, they gain new and extended knowledge about each other’s professions’ strengths and resources. Being humble to each other was expressed in this way: “We all have to be humble. If you think you have the right answer, you’ll stumble, no matter who carries out that arrogance. We depend very much on the types of people involved in the team.”

One participant in the health care professional group said respect for each other’s knowledge was an enrichment in the interdisciplinary work. Here is an example of that statement:

I am a physiotherapist; however, I’m well aware that other professions and health care personnel are important in rehabilitation. In some cases, we have overlapping knowledge, and it is essential that we respect each other. We are not a threat to one another. That is a prerequisite for achieving the person’s goals.

In our study, the different health care professionals and health care personnel had common roles and functions in the reablement team, however, they also had their specific roles. The reablement team was concerned about mono-disciplinary knowledge in the interdisciplinary collaboration. They argued that it is necessary for different professional groups to discuss mono-disciplinary issues. One person said, “It is simply that we are not going to be a woolly group of people who only have little knowledge about everything.” Due to this worry, they regularly had mono-disciplinary meetings. The professionals also appreciate mono-disciplinary conversations as well as interdisciplinary collaboration.

Discussion

The role of consultants and advisors

The health care professionals’ main role was to be consultants and advisors. Their role was to supervise and advise the health care personnel how to assist the older adult when practicing intensively prioritized activities. However, according to their professional role and responsibilities, they were conscious of which exercises required professional qualifications. Regardless, they had less direct contact with the older adults and rehabilitated them indirectly through the health care personnel.

The role of consultant consisted of planning, adjusting, conducting follow-ups to the interventions, delegating training, as well as supervising the home care personnel’s tasks as personal trainers. The health care professionals argued that it was useful and rational to teach the personal trainers to continue the work that had been started. In this way, their professional competence could be expanded to other older people who need it. However, according to Kjellberg et al28 it is important to notice the cultural differences and challenges for therapists concerning delegations and cooperation with the ordinary home care services. In ordinary rehabilitation services, the therapists perform the training exercises themselves, except for some delegations to students in clinical placement. Kjellberg et al28 highlighted that the therapists requested courses in coaching and supervision to better handle these tasks of delegation.

The role of personal trainer – person-centered approach

The evidence from our study revealed that the health care personnel experienced part of their role as personal trainers. This includes supporting the older person in performing daily training according to their own rehabilitation goals. As Winkel et al18 also point out, the role of the home carer is to support the participant in active engagement in the performance of tasks and at the same time perform those parts of the activities of daily living (ADL) that are too difficult for the participant. In accordance with Meldgaard Hansen and Kamp,21 this rehabilitative practice transforms the identity of the health care personnel from carers to personal home trainers of the older persons. Health care personnel perform rehabilitative body work, in which they activate the older person’s resources, potential, and capacities.

Our findings highlight how the role of the carer leads to a transformation in the role of personal trainers. Care work for the older person has traditionally been characterized by intimate contact through assistance with, for example, bathing and toileting.5 The growing field of literature of bodywork highlights the low status, stigma, and ambivalences related to this very intimate form of labor. Despite its demanding and complex character, care work is undervalued and low-paid.5

In our study, the personal trainers considered their new rehabilitative tasks to be very interesting and motivating by following the development of exercise-motivated older people toward greater self-reliance. They transform their care to a more person-centered approach by incorporating the person’s goals, person-led interventions, coaching, and involving the older person in decision-making processes. However, as Pettersson and Iwarsson15 point out, the person-centered approach might seem straightforward, however qualified person-centered problem identification, focusing on everyday occupation requires specialist competence. Thus, our findings highlight the important role of collaboration for all the different team members in reablement.

The transformation from the role of carer to the role of trainer is in accordance with the study of Hjelle et al,7 who points out the existence of a shift in the working culture of health care personnel. This shift represents a change from the perspective of viewing older persons as passive recipients, to empower them to be active recipients and use their resources. Interestingly, Meldgaard Hansen5 and Meldgaard Hansen and Kamp21 also argue that taking a resource and training approach to older persons may potentially lead to a more advantageous position for care workers in professional hierarchies. Undertaking training in reablement implies working according to detailed rehabilitation plans and goals and evaluating the older person’s progress. From this rehabilitative perspective, the role change from care work and doing things for the older person to supporting and supervising them as they perform their valued activities of everyday life.5 According to Pettersson and Iwarsson15 a holistic person-centered approach minimizes the need for support and services, and supports the older adult’s independence. This implies that the home care personnel’s work and role as carer becomes construed as being more professional.5,21 Meldgaard Hansen and Kamp21 also argue that home care workers have a transition from an identity as carers for older persons to having an identity as home trainers of the older persons.

Our results revealed that the health care personnel experienced perceived higher identity as they changed their work and roles from caring to personal trainer. Meldgaard Hansen5 and Meldgaard Hansen and Kamp21 also argue that rehabilitative programs are based on a perceived need for care workers to radically change their identity as carers for the older person to trainers for and in collaboration with the older person.

The role of interdisciplinary collaboration strengthens identities and competence

The findings in our study emphasize that interdisciplinary collaboration is an essential feature of the roles of all health care professionals and home care personnel in reablement. The new roles were characterized by collaboration across roles and, thus, learning from each other. In our study, the collaboration across roles was perceived as strengthening identities and increased competence. As Meldgaard Hansen and Kamp21 point out, this implies that the health care professionals and the home care personnel have respect for each other’s roles and humility for their own. This is in line with White et al,29 who argues that it can be a challenge to see one’s own and another’s role in the team, and it requires that each profession share and discuss their knowledge with each other.10,29 Sargeant et al 30 highlight that effective collaborative health care share common goals, understand and demonstrate respect for each other’s roles. However, lack of knowledge of the roles of the team members, and stereotypical views of other professionals can lead to lack of respect and limited opportunities to contribute fully as team members. Accordingly, the team-work may actually be a group of individuals working beside each other and not a team.30 In our study, the team discussed how interdisciplinary collaboration was working well with one another and learning from each other. This was also confirmed in a qualitative study by Moe and Brataas,16 who found that interdisciplinary collaboration in rehabilitation occurs when the equality between professions is taken seriously in terms of the integrated use of various professional skills in problem identification and rehabilitation planning. The collaboration did not weaken the professional identity but rather strengthened it. This is in line with the study by Birkeland et al,10 who point out that the participants roles’ had been dramatically changed when they started to collaborate closely with other professionals. However, although they had to share tasks with others in the team, they still had a perception that various professionals and health care personnel had different roles.

The formal and informal exchange of information and knowledge in interdisciplinary collaboration was experienced as essential for all the team members in our study. This was confirmed by Birkeland et al,10 who argue that removing organizational barriers gives access to new knowledge and learning. This was also pointed out in a study by Hjelle et al,7 who stated that the requirements of the system and the personal factors create dynamic cooperation and influence the new roles of the reablement team. Structural factors, such as informal and formal meetings, a low threshold for contacting each other, and discussing current challenges that have arisen in collaboration with the older person, contribute to a dynamic cross-health care professional and health care personnel collaboration. This provide opportunities for professionals and health care personnel to reflect on and evaluate the work and services provided to residents.7

Methodological considerations

Our study provides insight into interdisciplinary teams’ experiences of their roles in the reablement service. When researching and developing reablement services, it is important for the voices of those involved in the rehabilitation approach to be heard. In qualitative studies, the results are evaluated on their authenticity.26,27 One authentic feature of this study was the fact that the participants in the focus groups represented all the health care personnel who work in the reablement service and thus provided varied perspectives on the studied phenomenon. The local reablement project leader recruited the participants, and did not participate in the focus group discussion. All participants in the focus group discussions were engaged and enthusiastic. The reason for mixing the health care professional and the home care personnel in the focus group discussions was to enable reflection and discussion from all participants in the interdisciplinary team. However, using a mixed group may have influenced the results as participants may not have shared and fully discussed their opinions and experiences. Having focus group discussions separately with the two groups may have ensured that both groups had the opportunity to talk openly and not be influenced by the other group. However, they reflected on and discussed both the positive and less positive perspectives of the reablement service.

All of the authors analyzed the transcribed data separately and together several times to gain a deeper understanding of the data and to ensure the trustworthiness of the analysis. Credibility was further established by using representative text elements from the transcripts as quotations in reporting the results.26,27 In the results section, the quotes were in Norwegian originally and translated into English. In the translation we are aware the words may deviate from the speaker’s original words.

Conclusion and implications for practice

The health care professional group have the main responsibility for planning the reablement service in collaboration with the older person. However, they delegate the responsibility for practicing the daily rehabilitation to the personal trainers. The personal trainers’ work changed from body care to encouraging and supporting the older person to perform activities himself in a secure way. This shift in role was motivating and they experienced a perceived higher professional identity. The health care professionals and home care personnel collaborated closely across roles. The collaborating team who conduct a person-centered approach is described in a few international studies, however, there is still a gap in the research. Future research could further explore and describe the specific roles of different health care personnel in the reablement service.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the participants who willingly shared their reablement experiences with us. We also thank the local project leaders for recruiting the participants for our research.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

World Health Organization. World Report on Ageing and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. | ||

Kildal N, Nilssen E. Ageing policy ideas in the field of health and long-term care. Comparing the EU, the OECD and the WHO. In: Ervik R, Lindén TS, editors. The Making of Ageing Policy: Theory and Practice in Europe. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing; 2013:53–77. | ||

Aspinal F, Glasby J, Rostgaard T, Tuntland H, Westendorp RG. New horizons: Reablement – supporting older people towards independence. Age Ageing. 2016;45(5):574–578. | ||

Kjerstad E, Tuntland HK. Reablement in community-dwelling older adults: a cost-effectiveness analysis alongside a randomized controlled trial. Health Econ Rev. 2016;6(1):15. | ||

Meldgaard Hansen A. Rehabilitative bodywork: cleaning up the dirty work of homecare. Sociol Health Illn. 2016;38(7):1092–1105. | ||

Randström KB, Wengler Y, Asplund K, Svedlund M. Working with ‘hands-off’ support: a qualitative study of multidisciplinary teams’ experiences of home rehabilitation for older people. Int J Older People Nurs. 2014;9(1):25–33. | ||

Hjelle KM, Skutle O, Førland O, Alvsvåg H. The reablement team’s voice: a qualitative study of how an integrated multidisciplinary team experiences participation in reablement. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2016;9:575–585. | ||

Rabiee P, Glendinning C. Organisation and delivery of home care re-ablement: what makes a difference? Health Soc Care Comm. 2011;19(5):495–503. | ||

Sims-Gould J, Tong CE, Wallis-Mayer L, Ashe MC. Reablement, reactivation, rehabilitation and restorative interventions with older adults in receipt of home care: a systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(8):653–663. | ||

Birkeland A, Tuntland H, Førland O, Jakobsen FF, Langeland E. Interdisciplinary collaboration in reablement – a qualitative study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2017;10:195–203. | ||

Tuntland H, Aaslund MK, Espehaug B, Førland O, Kjeken I. Reablement in community-dwelling older adults: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:145. | ||

Tessier A, Beaulieu M-D, Mcginn CA, Latulippe R. Effectiveness of reablement: a systematic review. Healthc Policy. 2016;11(4):49–59. | ||

Tinetti ME, Charpentier P, Gottschalk M, Baker DI. Effect of a restorative model of posthospital home care on hospital readmissions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(8):1521–1526. | ||

Tuntland H, Espehaug B, Forland O, Hole AD, Kjerstad E, Kjeken I. Reablement in community-dwelling adults: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14:139. | ||

Pettersson C, Iwarsson S. Evidence-based interventions involving occupational therapists are needed in re-ablement for older community-living people: a systematic review. Br J Occup Ther. 2017;80(5):273–285. | ||

Moe A, Brataas HV. Interdisciplinary collaboration experiences in creating an everyday rehabilitation model: a pilot study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2016;9:173–182. | ||

Pellatt GC. Perceptions of interprofessional roles within the spinal cord injury rehabilitation team. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2005;12(4)143–150. | ||

Winkel A, Langberg H, Waehrens EE. Reablement in a community setting. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(15):1347–1352. | ||

Sandelowski M. Focus on research methods: whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(4):334–340. | ||

Liaaen JMA. Professional carers’ experience of working with reablement [Master thesis]. Trondheim: Fakultet for helse- og sosialvitenskap, Høgskolen i Sør-Trøndelag; 2015. | ||

Meldgaard Hansen A, Kamp A. From carers to trainers: professional identity and body work in rehabilitative eldercare. Gend Work Organ. 2018;25(1):63–76. | ||

Sandelowski M. What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res Nurs Health. 2010;33(1):77–84. | ||

Sandelowski M, Leeman J. Writing usable qualitative health research findings. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(10):1404–1413. | ||

Krueger RA. Moderating Focus Groups. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. | ||

Barbour RS, Kitzinger J, eds. Developing Focus Group Research. Politics, Theory and Practice. London: Sage Publications Ltd.; 1999. | ||

Kvale S, Brinkmann S. Interviews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing. 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: Sage; 2009. | ||

Malterud K. Systematic text condensation: a strategy for qualitative analysis. Scand J Public Health. 2012;40(8):795–805. | ||

Kjellberg PK, Ibsen R, Kjellberg J. From care and care to rehabilitation. Experience from Fredericia municipality (Fra pleje og omsorg til rehabilitering. Erfaringer fra Fredericia kommune). Copenhagen: Danish Health Institute; 2011. | ||

White MJ, Gutierrez A, McLaughlin C, et al. A pilot for understanding interdisciplinary teams in rehabilitation practice. Rehabil Nurs. 2013;38(3):142–152. | ||

Sargeant J, Loney E, Murphy G. Effective interprofessional teams: “contact is not enough” to build a team. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2008;28(4):228–234. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.