Back to Journals » HIV/AIDS - Research and Palliative Care » Volume 13

Rate and Predictors of Mortality Among Adults on Antiretroviral Therapy at Debre Markos Referral Hospital, North West Ethiopia

Authors Birhanu H , Alle A, Birhanu MY

Received 11 December 2020

Accepted for publication 17 February 2021

Published 2 March 2021 Volume 2021:13 Pages 251—259

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/HIV.S294111

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Bassel Sawaya

Haddis Birhanu,1 Atsede Alle,2 Molla Yigzaw Birhanu2

1Debre Markos Referral Hospital, Debre Markos, Ethiopia; 2Department of Public Health, College of Health Sciences, Debre Markos University, Debre Markos, Ethiopia

Correspondence: Molla Yigzaw Birhanu P. O. Box 269 Email [email protected]

Background: Human immunodeficiency virus/Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome is a chronic communicable disease with devastating global socio-economic, and political impacts commonly affecting the young and early adult populations. Ethiopia is doing well in controlling HIV/AIDS epidemic infection among African countries. This study set out to determine the mortality rate and its predictors among adults on antiretroviral therapy at Debre Markos Referral Hospital, northwest Ethiopia.

Methods: A hospital-based retrospective follow-up study was conducted from February to March 2018. A computer-generated simple random sample selected 480 cards of patients on antiretroviral therapy who were enrolled between February 2010 to January 2018. Epi-data Version 4.2 software was used for data entry and SPSS Version 25 for management and analysis. An adjusted hazard rate with a 95% confidence interval was used to identify significant predictors of mortality.

Results: The mortality rate was about 3.9 per 100 person-years. Cotrimoxazole prophylactic therapy (AHR: 2.99; 95% CI: 1.58, 5.70), being single (AHR: 2.37: 95% CI: 1.15, 4.87), non-disclosed status (AHR: 7.77; 95% CI: 3.76, 16.06), anemia (AHR: 2.16; 95% CI: 1.14, 4.09), bedridden (AHR: 6.11; 95% CI: 2.42, 15.41) or ambulatory (AHR: 2.16; 95%: 1.04, 4.51), presence of opportunistic infections (OIs) (AHR: 5.02; 95% CI: 1.70, 14.83) and tuberculosis (TB) co-infection (AHR: 5.57; 95% CI: 2.23, 13.88) were the significant predictors.

Conclusion and Recommendation: This study had a high mortality rate. Being single, bedridden, TB coinfection, anemia, and cotrimoxazole prophylaxis were the predictors of mortality. Therefore, psychological support and close follow-up for single, non-disclosed, non-adherent patients and early detection and treatment of anemia, tuberculosis, and OIs to reduce mortality is recommended.

Keywords: HIV, ART, mortality, predictors of mortality, Debre Markos, Ethiopia

Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus/Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) is a public health epidemic, which has created global economic, social and political repercussions. It is one of the leading causes of death globally resulting in significant premature mortality. Since the start of the epidemic, 76.1 million peoples were infected with the virus and 35 million peoples have died.1–3 The virus destroys immune cells, increasing the morbidity and mortality of multiple OIs and cancers.4

According to the 2017 report, 36.7 million peoples were living with HIV globally in 2016 of which 52% reside in sub-Saharan Africa.1,5 Adults comprise 34.5 million of these individuals of which more than half are women. During the same year, 1 million people died of HIV-related illnesses, which shows a 9% decrease from the previous year.1 East and South Africa regions are hardest hit by HIV, as they are home to 6.2% of the world’s population but more than half of the global HIV-infected peoples live there. In 2016, 43% of global new infections occurred in this region, with women remaining disproportionately affected.5

Ethiopia is one of the countries most seriously affected by HIV. People in Ethiopia living with HIV/AIDS in 2018 numbered approximately 1.2 million with prevalence of 1.7% for men and 2.6% for females.6 Adults newly infected with HIV in the 2016 were about 26,000.7

HIV/AIDS is an incurable disease with no effective vaccine; but due to the scale-up ART services, the disease has shifted to a chronic, manageable disease from being a fatal disease.8–10 After the initiation of ART, morbidity and mortality due to HIV/AIDS is significantly reduced with improved quality of life.11,12

In 2017, globally, death from AIDS-related morbidities decreased from 1.9 million in 2005 to 1 million by 2016. In East and South Africa regions, death from HIV decreased from 760,000 in 2010 to 420,000 in 2016 because of increased access to ART services. Although this pattern shows hope for the future, the current mortality in the region accounts for 42% of global deaths, signifying the need for collaborative efforts.5,13

The sustainable development goals released in 2015 aim to achieve improved quality and life expectancy.14 In the case of HIV-positive individuals, this goal can be achieved through awareness creation and delivery of ART services to all HIV-positive peoples irrespective of CD4 cell count after confirmation of the infection since early initiation of ART yields significant improvement in quality of life.10,15,16

Mortality due to HIV/AIDS is still devastating in different regions of the world. Despite the positive impacts of ART, in 2016, 18,000 adults died of AIDS-related illnesses in Ethiopia of which 61% were women. ART is a solution that may have averted these deaths but there is no way that 61% and 61% keeps reappearing.17,18

Even lower coverage of ART services at early stages results in significant reduction in mortality, increasing life expectancy more than 10 years. Knowing the factors that contributes to high mortality may help to address the disproportionate mortality from this disease in the East and South Africa regions.19–23 Therefore, this study determines mortality rate and its predictors among adults on antiretroviral therapies at the Debre Markos Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia in 2019. To improve the survival of people on ART, identifying the rate of mortality and its predictors are paramount.

Methods

Study Design, Area, and Period

A Hospital-based retrospective chart study at Debre-Markos Referral Hospital was conducted for the eight-year period between February 01, 2010 and January 31, 2018 G.C. The hospital, which serves 3.5 million people, is located in Debre Markos Town located at 299 km from Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia, and 265 km from Bahir-Dar, the major city of Amhara Regional State. Since ART initiation, approximately 12 0000 HIV-positive adults have been enrolled at Debre Markos Referral Hospital.

Population

The reference population was people living with HIV who started ART at Debre Markos Referral Hospital between February 01, 2010 and January 31, 2018 G.C. Adult individuals who have been on ART were the sampling unit. Adults 15 years or older who started ART care and treatment and received at least one follow-up visit at Debre Markos Referral Hospital were included in this study. Individuals with incomplete records and/or started on ART at another health institution were excluded.

Sample Size and Sampling Procedure

The sample size was calculated by two-population proportion formula considering significant variables from related literatures using online EPI INFO ™ Version 7.2.2 software yielding a sample size of 480 patient records, which were subsequently drawn through computer-generated simple random sampling from the source population previously described.

Study Variables

Mortality is the dependent variable. Explanatory (independent) variables are age, sex, residence, religion, ethnicity, marital status, educational status, employment status, disclosure status, WHO staging, baseline CD4 count, Hemoglobin (Hgb) status, OIs, functional status, baseline prophylaxis, ART eligibility criteria, nutritional status and ART regimen, first line, second line, side effects, adherence, and change in regimen.

Operational Definitions

Mortality: death of HIV-infected adults after initiation of ART.

Incomplete record: patient record missing one or more of the identified independent variables (eg, baseline CD4 count, WHO stage, functional status, Tb status)

Lost to follow-up: not on follow-up for ≥1 month but <3 months.

Dropout: no follow-up for ART for more than 3 months.

Transfer out: patient transferred to another health facility for follow-up per chart documentation.

Functional status: Working – able to perform usual work in and outside home; ambulatory – able to perform daily living activities; bedridden – unable to perform daily living activities.

Survival time: time that the patient stays alive post-ART initiation.

Adherence: Good (>95%) – if the percentage of missed doses is ≤2 doses of 30 doses or ≤3 doses of 60 doses; Fair: (85–94%) – if the percentage of missed doses is between 3 and 5 doses of 30 doses or 4–9 doses of 60 doses; poor: (<85%) – if missed dose is ≥6 doses of 30 doses or ≥10 doses of 60 doses, as documented by the ART physician.

Data Collection Tool and Procedure

The data abstraction checklist was adapted from ART entry and follow-up forms currently used by ART clinics at Debre Markos referral hospital. The data extraction tool consists about baseline socio-demographic factors, baseline clinical conditions, baseline ART regimen and follow-up factors. Paper and electronic-based database were the sources for data extraction. To ensure data quality, prepared bachelor nurses, working at the ART clinic of Debre Markos Referral Hospital, recruited as data collectors as well as a supervisor. Two day training was provided for both data collectors and the supervisor. To check the consistency of understanding of participants, a pretest was conducted on 10% of the total sample size. During the data extraction period, the supervisor and principal investigators performed daily follow-up and supervision.

Data Management and Analysis

The data abstraction checklist was adapted from ART entry and follow-up forms currently used by ART clinic at Debre Markos Referral Hospital. The data extraction tool consists of baseline socio-demographic factors, clinical conditions, ART regimen and follow-up factors. Paper and electronic-based database were the sources for data extraction. To ensure data quality, bachelor prepared nurses, working at the ART clinic of Debre Markos Referral Hospital, were recruited as data collectors as well as a supervisor. A two-day training session was provided for both data collectors and the supervisor. To check the consistency of understanding of participants, a pretest was conducted on 10% of the total sample size. During the data extraction period, the supervisor and principal investigators performed daily follow-up and supervision.

Results

Socio-Demographic Characteristics

Of 480 patient record cards, 22 cards were excluded from the analysis due to incompleteness for clinically important variables at the baseline. The median age of patients was 34 (IQR, 28–40), with slightly more than half (57.9%) being females and primarily urban residents (68.8%) (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Socio-Demographic Characteristics of HIV-Infected Adults Initiating Antiretroviral Therapy in Debre Markos Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia, 2018 (n=458) |

Baseline Clinical and Laboratory Characteristics

Clinically, 214 (46.7%) and 204 (53.3%) of participants were on stage I+II and III+IV, respectively. The median CD4 count was 185 (IQR, 95–286.25) cell/mm3. The median Hgb level was 13 mg/dl (IQR, 11.4–14). The median baseline BMI was 19.5 (IQR, 17.9–21.8) kg/m2. Two hundred eighty-six (62.4%) of patients had OIs, while reports found 77 (26.9%) with unexplained chronic diarrhea for more than month, 73 (25.5%) with oral candidiasis, 55 (19.2%) with recurrent upper airway infection, 37 (12.9%) with herpes zoster, 14 (4.9%) with esophageal candidiasis, and 13 (4.5%) with cryptococcal meningitis. Kaposi sarcoma and toxoplasmosis accounted for five (1.7%) and 12 (4.2%) of OIs, respectively. Most patients had good adherence with 94.5% and 94.1% for ART and CPT, respectively. Only one patient had a regimen change due to new onset TB (Tables 2 and 3).

|

Table 2 Baseline Clinical and Laboratory Characteristics of HIV-Infected Adults on Antiretroviral Therapy at Debre Markos Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia, 2018. (n=458) |

|

Table 3 Follow-Up Characteristics of HIV-Infected Adults Initiating Antiretroviral Therapy at Debre Markos Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia, 2018 |

The Incidence Rate of Mortality

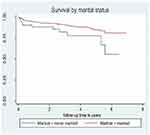

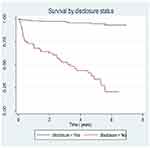

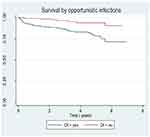

A total of 458 patients contributed to 1406.8 person-years of observations and 55 patients died giving mortality rate of 3.9 per 100 person-years (95% CI: 3.00, 5.09) of observation. The estimated mortality was 4.8% and 1.1% at 6 and 12 months, respectively. During the entire follow-up time, 94 (20.5%) patients were transferred out and 68 (14.8%) patients were lost to follow-up. The survival probability of patients on ART [Figure 1], the survival status over marital status [Figure 2], the survival status of HIV patients over disclosure (Figure 3), and survival status over opportunistic infection [Figure 4] were compared graphically.

|

Figure 2 Survival status of HIV positive patients based on their marital status in Debre Markos Referral Hospital, northwest Ethiopia, January 2018. |

|

Figure 3 Survival status of adults based on HIV disclosure status category upon initiation ART in Debre Markos Referral Hospital, northwest Ethiopia, January 2018. |

|

Figure 4 Survival status of HIV positive adults based on functional status upon initiation ART in Debre Markos Referral Hospital, northwest Ethiopia, January 2018. |

Bivariable and Multivariable Analysis

In bivariable cox regression analysis; marital status, disclosure status, WHO clinical stage, CD4 count, functional status, baseline OIs, TB co-infection, BMI, Hgb level, drug side effect, adherence to ART & CPT were the significant variable with p-value less than 0.05. In multivariable cox regression analysis; non-adherence to CPT (AHR: 2.99; 95% CI: 1.58, 5.70), being single (AHR: 2.37: 95% CI: 1.15, 4.87), non-disclosed status (AHR: 7.77; 95% CI: 3.76, 16.06), anemia (AHR: 2.16; 95% CI: 1.14, 4.09), bedridden (AHR: 6.11; 95% CI: 2.42, 15.41) or ambulatory (AHR: 2.16; 95%: 1.04, 4.51) functional status, presence of OIs (AHR: 5.02; 95% CI: 1.70, 14.83) and TB co-infection (AHR: 5.57; 95% CI: 2.23, 13.88) were the significant predictors of mortality about HIV positive adults on ART (Table 4).

|

Table 4 Bivariable and Multivariable Cox Regression Table for Predictors of Mortality on HIV-Infected Adults Receiving ART at Debre Markos Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia, 2018 |

Discussion

This retrospective cohort study showed the rate of mortality and significant predictors among adults on ART treatment in Debre Markos Referral Hospital, Ethiopia. The significant predictors were single in marital status, non-disclosed status, bedridden in functional status, and presence of OIs, TB co-infection, anemia and non-adherence to CPT.

This study found that the mortality rate among adults on ART treatment was 3.9 (95% CI: 3.00, 5.09) per 100 Person-years of observation. This finding is higher when we compared with a study conducted in China, which was 2.63 in 2015.24 This might be because of a larger proportion of patients at advanced stages (stage III & IV) of the disease in the current area (53.3%) than in China (41.2%). Advanced clinical stages reflect the worst health condition of the patient and it has strong association with mortality in different studies.25,26 The result of this study is comparable to a study done in Thailand, which was 3.5 in 2015.32

The current study showed a lower mortality rate than a study conducted in five ART sites in Nepal which was 6.3 in 2011.27 This could be due to the time gap between studies and larger proportion of patients at earlier stages (stage I & II) of the diseases (46.7%) in the current study area than in Nepal (30%). Studies from different countries showed that patients who present at earlier clinical stages had better survival.28,29 The finding of this study showed a lower mortality rate than a study conducted in Andhra Pradesh, India, which was 8.09 in 2013.30 This could be due to low adherence to ART (61.1%) in India. The current study result was lower than a study conducted in a tertiary hospital in Eastern, India, which was 7.66 in 2010.31 This could be due to higher prevalence of TB (38.4%) at baseline, which might be responsible for the high death in India.

The rate of mortality in the current study is lower than a study conducted in Jimma university specialized hospital, which was 5.3 in 201032 and in kharamara hospital in Somalia, Ethiopia which was 5.15 in 2010.33 This could be more due to higher adherence level to ART in our study area than in Jimma (78%) and in Somalia (57%).

The current study identified that those individuals who were single had a higher probability of death when compared to those who were married (AHR= 2.24; 95% CI: 1.10, 4.55). A study conducted in Somali region, Eastern Ethiopia also found that there was a strong association between single marital status and survival in PLHIV.33 This difference might be because of psychological support from partner and society, ability to accept facts and adhere to ART in individuals.33

This study showed that those patients with non-disclosed HIV status had eight times higher probability of death than those who disclosed their status (AHR=8.04; 95% CI: 3.87, 16.66). A study conducted in Jinka hospital, South Ethiopia also showed that non-disclosed HIV status was significantly associated with mortality.29 This might be due to distress, loneliness, poor family relationship and adherence to ART as a way to hide having the disease.29

The result of this study showed that bedridden individuals had a higher probability of death than those who were working in their functional status (AHR= 5.72; 95% CI: 2.30, 14.23). This is consistent with the finding obtained from Nepal, Myanmar and Nigeria.25,27,34 Studies from different parts of Ethiopia also identified a strong association between ambulatory/bedridden functional status and survival of patients on ART.29,33,35 This could be due to advanced clinical stage of the disease associated with the worst health conditions and complications.27

The current study showed that patients who had TB had a higher probability of death than those who had no TB co-infection (AHR=6.04; 95% CI: 2.47, 14.76). The finding of studies conducted previously in different countries showed similar with this study.31,33,36,37 This could be due to the fact that TB is the leading cause of death worldwide and the virulence of the bacteria increases in HIV-infected patients because of their suppressed immunity due to HIV.38

This study identified that patients who had an opportunistic infection at baseline had a high likelihood of mortality than those who had no OIs (AHR=4.44; 95% CI: 1.60, 12.33). A similar study from Armed military Hospital, Ethiopia found that those patients who had OIS had higher rates of mortality than those who were free of OIs.35 This could be due to the more virulent effect of OIS on peoples who were living with HIV/AIDS.

In this study, it was found that those patients who had anemia had a higher probability of death than those who had no anemia (AHR=2.08; 95% CI: 1.12, 3.85). Studies done in Burkina Faso, Cameroon and Cape town, South Africa identified that those patients who had anemia were at higher risk of mortality than those who had no anemia.26,37,39 Studies conducted in Somalia, eastern Ethiopia and Nekemte Referral Hospital, western Ethiopia, also identified that patients who had moderate to severe anemia had higher rates of mortality.28,33 This could be due to patients who had anemia were at higher risk TB, OIS and progression to AIDS and further complications.33,39

This study identified that those patients who were non-adherent to cotrimoxazole prophylactic therapy were three times more likely to die when compared to those who were adherent (AHR=3.10; 95% CI: 1.64, 5.87). It is supported by studies conducted in Harare, eastern Ethiopia and Yangon, Myanmar.25,38 This could be due to the virulent effect of opportunistic infection on people living with HIV/AIDS.38

Conclusion

The rate of mortality was high in this study area. The final cox regression model identified that single marital status, non-disclosed HIV status, bedridden and ambulatory in functional status impairment, baseline OIs, TB, anemia and non-adherence to CPT were predictors of mortality for people living with HIV/AIDS. The effective symptom management, multi-dimensional care, palliative and supportive care should be provided. Then, populations at risk of adverse outcomes deserve more attention and should be considered for the “refill” care option for stable patients.

Recommendations

- Strengthen health care providers to psychological support and closely follow those single people living with HIV/AIDS.

- Individuals who had TB, anemia, impaired functional status and OIS should be followed closely and health care providers should be empowered to detect these factors early.

- Health care providers should give awareness creation and information on the benefits of CPT to all HIV positive individuals routinely.

- Debre Markos Hospital should monitor, support and create strong linkage with the contributory hospitals and health centers to enhance ART service quality and reduce mortality.

- Perform increased research, preferably prospective cohort study on the mortality and its predictors on PLHIV.

Abbreviations

AHR, adjusted hazard ratio; AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; ART, antiretroviral therapy; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; CHR, crude hazard ratio; CPT, cotrimoxazole prophylaxis; Hgb, hemoglobin; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; PLHIV, people living with human immunodeficiency virus; TB, tuberculosis; SPSS, Statistical Package for Social Sciences; WHO, World Health Organization.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The study was conducted after obtaining ethical clearance from research ethical committee of Debre Markos University, College of Health Sciences. Formal permission was obtained from Debre Markos Referal Hospital and data were extracted from their medical records after written informed consent was obtained from the study population. To keep the confidentiality, the information of the study participants was not disclosed to anyone other than the principal investigators. Generally, this study was conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to Participate

We received consent from Debre Markos Referral Hospital for possible publication.

Acknowledgments

First and for most thanks to the Almighty GOD who is our power. Our gratitude extends to Debre Markos Referral Hospital for providing us the necessary information and facilitating conditions. Finally, we are also grateful to data collectors and supervisors for giving us their valuable time.

Author Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; agreed to submit to the current journal; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interests in this work.

References

1. UNAIDS. UNAIDS report on global AIDS epidemics. Tech. Rep. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2017.

2. Woradet S, Chaimay B, Chantutanon S, Phuntara S, Suwanna K. Characteristics and demographic factors affecting mortality among HIV/AIDS patients in the Southern Region of Thailand. Asia J Public Health. 2012;3(3):86–93.

3. amfAR. World AIDS statistics. The foundation for AIDS; 2014.

4. Brooks JT, Kaplan JE, Holmes KK, Benson C, Pau A, Masur H. HIV-associated opportunistic infections—going, going, but not gone: the continued need for prevention and treatment guidelines. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(5):609–611. doi:10.1086/596756

5. UNAIDS. AIDS epidemic update. UNAIDS; 2017.

6. WHO. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/health-topics/hivaids .

7. UNAIDS. UNAIDS country factsheets, Ethiopia; 2016.

8. Dorfman D, Saag MS. Decline in locomotor functions over time in HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 2014;28(10):1531–1532. doi:10.1097/QAD.0000000000000302

9. Kharsany AB, Karim QA. HIV infection and AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa: current status, challenges and opportunities. Open AIDS J. 2016;10:34. doi:10.2174/1874613601610010034

10. Piot P, Karim SSA, Hecht R, et al. Defeating AIDS—advancing global health. Lancet. 2015;386(9989):171–218. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60658-4

11. Organization WH. Consolidated Guidelines on the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach. World Health Organization; 2016.

12. Egger M, May M, Chêne G, et al. Prognosis of HIV-1-infected patients starting highly active antiretroviral therapy: a collaborative analysis of prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360(9327):119–129. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09411-4

13. UNAIDS. Global AIDS update. UNAIDS; 2016.

14. Available from: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/?menu=1300.

15. Lima VD, Lourenço L, Yip B, Hogg RS, Phillips P, Montaner JS. AIDS incidence and AIDS-related mortality in British Columbia, Canada, between 1981 and 2013: a retrospective study. Lancet HIV. 2015;2(3):e92–e97. doi:10.1016/S2352-3018(15)00017-X

16. Karim SSA, Karim QA, Baxter C. Antibodies for HIV prevention in young women. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2015;10(3):183. doi:10.1097/COH.0000000000000147

17. UNAIDS. Country fact sheet, Ethiopia. UNAIDS; 2016.

18. FMOH E. Ethiopian FMOH national comprehensive HIV prevention, care and treatment training for health care providers; 2017.

19. Tanser F, Bärnighausen T, Grapsa E, Zaidi J, Newell M-L. High coverage of ART associated with decline in risk of HIV acquisition in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Science. 2013;339(6122):966–971. doi:10.1126/science.1228160

20. Mossong J, Grapsa E, Tanser F, Bärnighausen T, Newell M-L. Modelling HIV incidence and survival from age-specific seroprevalence after antiretroviral treatment scale-up in rural South Africa. AIDS. 2013;27(15):2471. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000432475.14992.da

21. Nsanzimana S, Remera E, Kanters S, et al. Life expectancy among HIV-positive patients in Rwanda: a retrospective observational cohort study. Lancet Global Health. 2015;3(3):e169–e177. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70364-X

22. Reniers G, Slaymaker E, Nakiyingi-Miiro J, et al. Mortality trends in the era of antiretroviral therapy: evidence from the network for analysing longitudinal population based HIV/AIDS data on Africa (ALPHA). AIDS. 2014;28(4):S533. doi:10.1097/QAD.0000000000000496

23. Buse K, Hawkes S. Health in the sustainable development goals: ready for a paradigm shift? Global Health. 2015;11(1):13. doi:10.1186/s12992-015-0098-8

24. Tang Z, Pan SW, Ruan Y, et al. Effects of high CD4 cell counts on death and attrition among HIV patients receiving antiretroviral treatment: an observational cohort study. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):3129. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-03384-7

25. Kyaw AT, Sawangdee Y, Hunchangsith P, Pattaravanich U. Survival rate and socio-demographic determinants of mortality in adult HIV/AIDS patients on anti-retrovial therapy (ART) in Myanmar: a registry based retrospective cohort study 2005–2015. J Health Res. 2017;31(4):323–331.

26. Poda A, Hema A, Zoungrana J, et al. Mortality of HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy in a large public cohort in West Africa, Burkina Faso: frequency and associated factors. Adv Infect Dis. 2013;3(04):281. doi:10.4236/aid.2013.34043

27. Bhatta L, Klouman E, Deuba K, et al. Survival on antiretroviral treatment among adult HIV-infected patients in Nepal: a retrospective cohort study in far-western Region, 2006–2011. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13(1):604. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-13-604

28. Hambisa MT, Ali A, Dessie Y. Determinants of mortality among HIV positives after initiating antiretroviral therapy in Western Ethiopia: a hospital-based retrospective cohort study. Isrn Aids. 2013;2013:2013. doi:10.1155/2013/491601

29. Tachbele E, Ameni G. Survival and predictors of mortality among human immunodeficiency virus patients on anti-retroviral treatment at Jinka Hospital, South Omo, Ethiopia: a six years retrospective cohort study. Epidemiol Health. 2016;38:38. doi:10.4178/epih.e2016049

30. Bajpai R, Chaturvedi H, Jayaseelan L, et al. Effects of antiretroviral therapy on the survival of human immunodeficiency virus-positive adult patients in Andhra Pradesh, India: a retrospective cohort study, 2007–2013. J Preventive Med Public Health. 2016;49(6):394. doi:10.3961/jpmph.16.073

31. Bhowmik A, Bhandari S, De R, Guha SK. Predictors of mortality among HIV–infected patients initiating anti retroviral therapy at a tertiary care hospital in Eastern India. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2012;5(12):986–990. doi:10.1016/S1995-7645(12)60187-4

32. Seyoum D, Degryse J-M, Kifle YG, et al. Risk factors for mortality among adult HIV/AIDS patients following antiretroviral therapy in Southwestern Ethiopia: an assessment through survival models. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(3):296. doi:10.3390/ijerph14030296

33. Damtew B, Mengistie B, Alemayehu T. Survival and determinants of mortality in adult HIV/Aids patients initiating antiretroviral therapy in Somali Region, Eastern Ethiopia. Pan African Med J. 2015;22(1). doi:10.11604/pamj.2015.22.138.4352

34. Dalhatu I, Onotu D, Odafe S, et al. Outcomes of Nigeria’s HIV/AIDS treatment program for patients initiated on antiretroviral treatment between 2004–2012. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0165528. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0165528

35. Kebebew K, Wencheko E. Survival analysis of HIV-infected patients under antiretroviral treatment at the Armed Forces General Teaching Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiopian J Health Develop. 2012;26(3):186–192.

36. Lee SH, Kim K-H, Lee SG, et al. Causes of death and risk factors for mortality among HIV-infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2013;28(7):990–997. doi:10.3346/jkms.2013.28.7.990

37. Poka-Mayap V, Pefura-Yone EW, Kengne AP, Kuaban C. Mortality and its determinants among patients infected with HIV-1 on antiretroviral therapy in a referral centre in Yaounde, Cameroon: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2013;3(7):e003210. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003210

38. Digaffe T, Seyoum B, Oljirra L. Survival and predictors of mortality among adults on antiretroviral therapy in selected public hospitals in Harar, Eastern Ethiopia. J Trop Dis. 2014;2(148):2. doi:10.4172/2329-891X.1000148

39. Kerkhoff AD, Wood R, Cobelens FG, Gupta-Wright A, Bekker LG, Lawn SD. The predictive value of current haemoglobin levels for incident tuberculosis and/or mortality during long-term antiretroviral therapy in South Africa: a cohort study. BMC Med. 2015;13:70. doi:10.1186/s12916-015-0320-9

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.