Back to Journals » Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics » Volume 12

Rape Survivors’ Sorrow: Major Depressive Symptoms and Sexually Transmitted Infection Among Adolescent Girls, Southwest Ethiopia

Authors Belay EA, Deressa BG

Received 30 July 2021

Accepted for publication 20 October 2021

Published 29 October 2021 Volume 2021:12 Pages 91—98

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AHMT.S331843

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Alastair Sutcliffe

Eyob Asefa Belay,1 Beshea Gelana Deressa2

1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Jimma University, Jimma, Ethiopia; 2Department of Health Policy and Management, Jimma University, Jimma, Ethiopia

Correspondence: Beshea Gelana Deressa

Department of Health Policy and Management, Jimma University, PO BOX: 378, Jimma, Ethiopia

Tel +251921833996

Email [email protected]

Purpose: Rape is one of the sexual violence acts against women globally. Adolescent girls are vulnerable to this event and experience more severe and long-standing adverse effects. Thus, this study aimed to examine major depressive symptoms and associated factors and the level of sexually transmitted infection among female adolescents evaluated for rape cases at Jimma Medical Center.

Patients and Methods: Institutional-based cross-sectional study was conducted among adolescent girls assessed for rape cases in Jimma Medical Center. Data were collected using structured questionnaire and entered into Epi Data version 3.1 then exported to SPSS version 21.0 for analysis. Descriptive statistics and regression analyses were carried out.

Results: A total of 174 raped adolescent females took part in the study. Of the total participants, 155 (89.1%) of these individuals had major depressive symptoms (95 CI %, 84.5– 93.7%), while 85 (48.9%) of them had an STI (95% CI, 41.1– 56.9%). From logistic regression, place of residence (AOR 14.65, 95%, (p=0.002)), attending school currently (AOR 9.01, 95%, p=0.004), raped by hitting (AOR 17.67, 95%, p< 0.001) and unwanted pregnancy (AOR 14.68, 95%, p=0.001) were the variables associated with major depression.

Conclusion: This study indicates that adolescents were suffering from several encumbrances like major depressive symptoms, sexually transmitted diseases and unwanted pregnancy. It also indicated that place of residence, school attending, and unwanted pregnancy had an association with major depressive symptoms. Therefore, the need for a comprehensive approach while treating this vulnerable group is highly recommended.

Keywords: sexual assault, rape victims, sexual violence, Jimma, rape survivors

Introduction

Gender-based violence (GBV) is the common health problem and human rights violation that goes underreported and unsolicited globally. It is devoid of all social, economic, and national barriers.1,2 Sexual violence is a type of GBV defined as any sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act, unwanted sexual comments or advances, or acts to traffic, or otherwise directed, against a person’s sexuality using coercion, by any person regardless of their relationship to the victim, in any setting, including but not limited to home and work.3 Rape is a type of sexual violence that causes intense trauma and often has long-term health implications.4

Domestic and sexual violence are all on the rise in the current situation.5 Globally, about 35.6% of women have experienced sexual violence, with widely varying prevalence estimates.6 Adolescents and young adults are 4 times more likely to be victims of sexual assault than women in all other age groups.7 Across 30 LMICs, 15% of sexually experienced adolescents and over 11% of young adult women report that their first sexual experience was forced or coerced.8 In sub-Saharan Africa 15–40% of sexual violence among adolescent girls was reported.9 In Ethiopia, a country-wide report indicated that the prevalence of sexual violence and rape was 39.33% and 13.02%, respectively.10 Other studies also reported a high prevalence of sexual violence or rape in Ethiopia among adolescent girls; 20.4% in Jimma town,11 25% in Harari town,12 and 41.1% in Madda walabu.1

Adolescents are at higher risk of sexual violence due to behavioral, lifestyle, and relationship issues. Accordingly, having multiple sexual partners, frequent watching of pornography, and use of alcohol or other drugs, are factors for higher levels of sexual violence victimization.1,13 Also having regular boyfriends, being sexually active, having female or male friends who drink alcohol, witnessing their mothers being beaten by their partners or husband were revealed as risk factors for sexual violence.14

Being a victim of rape at a young age is associated with more long-term and severe consequences, like mental disorders.7,15 For example, among adolescents evaluated for rape in Kenya, 85.4% of them reported moderate to severe depressive symptoms.15 Studies revealed that adolescents under 16 who had separated parents, were older than 16 years old, and did not attend secondary school compared to those in primary school had more depressive symptoms.15 On the other hand, higher depressive symptoms were reported among adolescents with a history of sexual violence as compared to those with no history, unmarried girls who saw their father beating their mother, and who faced perpetrators and bullying.16,17 Similarly, sexual violence is reported to cause genital trauma, unwanted pregnancy, abortion, and risky sexual behaviors.1,11

Several studies in Ethiopia have found a high rate of rape among adolescents.11,18–21 However, there has been a scarcity of research on determining the level of major depressive symptoms and associated factors among raped adolescents. As a result, the aim of this study was to determine the extent of major depressive symptoms and related factors, as well as the level of sexually transmitted infection among adolescents evaluated at Jimma University Medical Center for rape cases.

Patients and Methods

Study Area and Period

The research was carried out at Jimma University Medical Center, which is located in Jimma town, in Southwestern Ethiopia, 343 kilometers from Addis Ababa. It serves as a referral hospital for the southwestern region of the country. Most of the adolescent girls complaining of rape cases come from the surrounding hospitals, health centers, and police stations, accompanied by their families, police staff, or alone. The sexual violence unit has its own trained staff (nurses, obstetricians and gynecology residents and seniors) who were involved in the evaluation of cases during the study period, December 1/2019–July 30/2020.

Study Design and Population

An institution-based cross-sectional study was conducted among adolescent girls evaluated for rape at Jimma University Medical Center.

Sampling and Eligibility Criteria

All adolescent girls aged between 10-19 years who come to JUMC for evaluation of rape during the study period were interviewed consecutively and those who had mental illness before the incident of the rape were excluded.

Measures

The dependent variable was measured following assessment for the following major depressive symptoms of participants: poor appetite, bad sleep, easily frightened, blaming yourself for what happened, hating others for what has happened to you, feeling unhappy, crying more than usual, losing interest in sexual intercourse, becoming addicted to alcohol or substances, losing interest in things, feeling that you are a worthless person, thinking of ending your life, trying to take your life, and feeling tired and depressed all the time. Adolescents with any of the major depressive symptoms indicated under the Depression DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria were considered as having major depressive symptoms.

Variables that have been theoretically, empirically and conceptually linked to major depressive symptoms for raped adolescents, like socio-demographic and risk-related variables (age, religion, occupation, residency area, marital status, educational level, family income, currently attending school, attending school before rape, mechanism of assault, number of assaults, whether perpetrator known by victim, unwanted pregnancy, abortion, place of assault, type of intercourse, age at intercourse, age of perpetrator, chewing chat, stimulant drugs use, alcohol consumption, and previous rape) were included as explanatory variables.

Participants were also assessed for sexually transmitted infection (STI) if they had a genital ulcer and abnormal vaginal discharge, in addition to venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL), Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positive test findings, to determine the level of sexually transmitted infection. The information was taken from the patient’s documentation.

Data Analysis

Data were checked for completeness and entered into Epi Data version 3.1, then exported to SPSS version 21 for further data cleaning and analysis. Descriptive statistics were employed for the continuous variables, and they were described by the mean and standard deviation (SD), whereas the categorical variables were described by frequency and percentage.

Bivariate analysis was performed to identify factors associated with major depressive symptoms. Variables having a p-value <0.2 in the bivariate analysis were selected for the multivariate logistic regression modeling, for adjustment of confounding effects between explanatory variables. Adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with 95% CI was computed, and variables having p-value <0.05 in the multivariate logistic regression model were considered as statistically significant. The odds ratio was also used to determine the strength of association between independent variables and the outcome variable.

Results

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Adolescent Rape Victims

In this study, 174 adolescent girls were interviewed. More than two-thirds of participants were found to be late adolescents. Regarding the residence of the adolescents who had been raped, 92 (52.9%) were from urban areas. More than half of the study participants were Oromo in their ethnicity. Almost half of the study participants were Muslims in religion (49.4%), followed by orthodox 50 (28.7%). The vast majority (97.1%) of study participants were unmarried. Nearly half, 83 (47.7%), of the study subjects’ family monthly income was below 500 ETB. Seventy-nine (45.4%) of the study subjects were attending school before the rape happened to them (See Table 1).

|

Table 1 Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Raped Adolescent Girls (n=174) |

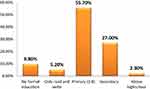

Regarding the level of education among adolescent girls who have been evaluated for rape, more than half (57.5%) of them attended primary education, followed by secondary education, which was 47 (27.0%) (see Figure 1).

|

Figure 1 Raped adolescent girls’ level of education assessed in JUMC (n=174). |

Regarding the parental condition of the participants, more than half, 96 (55.5%), of the study participants parents were both alive, whereas 41 (23.6%), 25 (14.4%) and 12 (6.9%) were dead, only mother alive and only father alive, respectively. More than one-third, 67 (38.5%), of adolescent girls live with both their parents and 40 (23.0%) respondents live with their employers.

Predisposing Characteristics of the Participants

In this study slightly more than half, 89 (51.1%), of the study participants had had sexual intercourse before the index event. The mean and SD of age at the first sexual intercourse were 14.9 and 1.74 years, respectively. Among the study participants who had had sexual intercourse before the index event, 52 (58.4%) of them had engaged in sexual intercourse by being forced. The majority, 156 (89.7%), of the study participants knew the person who raped them. Forty-eight (30.8%) respondents had forced sexual intercourse from a neighbor. Regarding the type of sexual intercourse, almost all, 170 (97.7%), study participants experienced penetrative vaginal intercourse. Regarding the estimated age of the perpetrator, 152 (87.2%) of them were found to be older than the victims and 10 (5.7%) were found to be younger than the victims (see Table 2).

|

Table 2 Predisposing Characteristics Among Raped Adolescent Girls Evaluated in JUMC, 2020 |

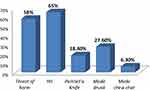

From 174 rape cases evaluated in JUMC, 101 (58.0%) of the rapes were conducted by threats of harm. Similarly, from the total study subjects, nearly two-thirds of the rapes were conducted through hitting of the victims (see Figure 2).

|

Figure 2 The way of rape among adolescent girls evaluated for rape cases in JUMC (n=174). |

This study also found that 55 (31.6%), 17 (9.8%) and 22 (12.6%) of perpetrators drink alcohol, chew chat and take any type of drugs, respectively, at the time of assault. On the side of the victims, the study participants reported that nearly half, 85 (48.9%), of them had been raped once, 77 (44.3%) raped two to four times and 12 (6.9%) more than five times, respectively.

Pregnancy-Related Characteristics Among Raped Adolescents

More than two-thirds, 118 (67.2%), of the study participants had had an unwanted pregnancy, of which 56 (47.5%) were less than 12 weeks gestation and 62 (52.5%) were over 12 weeks gestation. Among pregnant adolescent girls, the majority, 110 (91.5%), decided to terminate the pregnancy and only 10 (8.5%) decided to continue. Of total participants, only 52 (29.9%) of the adolescent girls had a history of abortion before.

STI Status Among Raped Adolescent Girls Assessed with Rape in JUMC

In this study, among adolescent girls screened for STI, 29 (16.7%), 26 (14.9%) and 10/168 (10%) were found to be positive for VDRL, HBsAg and HIV, respectively. Twenty-eight (16.1%) of them had an ulcer in genitalia and 50 (28.7%) of them had unusual vaginal discharge. Generally, nearly half, 85 (48.9%), of the study participants developed an STI after the event (see Table 3).

|

Table 3 STI Status Among Adolescent Girls Evaluated for Rape in JUMC |

Depression Status Related to Rape Among Adolescent Girls

In this study, 118 (67.8%) study participants often had a headache. Similarly, 56 (47.5%) study participants had poor appetite, as well as 111 (63.8%) individuals who had bad sleep disorder. More than half, 112 (64.4%), of the study participants were easily frightened after the event happened. The majority, 148 (85. 1%), of individuals felt unhappy after the event happened and 112 (64.4%) of them feel tired and depressed all the time (see Table 4).

|

Table 4 Major Depressive Symptoms Related with Rape Among Adolescent Girls Evaluated in JUMC |

In this study the magnitude of major depressive symptoms among adolescent girls related to rape was 89.1% (95 CI%, 84.5–93.7%). The level of major depression was 109 (90.8%) among individuals who are from 15 to 18 years old and it was 46 (85.2%) among individuals from 10 to 14 years old. Similarly, the level of major depression was 90 (90.9%) among individuals who were older than 14 at first sex and 65 (86.7%) among individuals aged 14 or younger at first sex.

Factors Associated with Major Depressive Symptoms Among Raped Adolescents

Multivariate analysis indicated that the odds of having major depressive symptoms was 14.6 times higher among adolescent girls who are resident in urban areas compared to respondents living in rural areas (AOR 14.65, 95% CI 2.6, 83.3, p=0.002).

The odds of having major depressive symptoms was 9.1 times higher among individuals who are not currently in school compared to their counterparts (AOR 9.01, 95% CI 2.05, 40.35, p=0.004). Adolescents who were raped by hitting were 17.6 times more likely to develop major depressive symptoms than those raped without hitting (AOR 17.7, 95% CI 3.58, 87.2, p<0.001). Similarly, the odds of having major depressive symptoms were 14.8 times higher among individuals who have an unwanted pregnancy compared to their counterparts (AOR 14.7, 95% CI 3.09,71.43, p=0.001) (see Table 5).

|

Table 5 Binary and Multivariate Logistic Regression Model to Identify Factors Associated with Major Depressive Symptoms Among Adolescent Girls Evaluated for Rape Cases in JUMC, Southwest Ethiopia |

Discussion

This study revealed that significant numbers of participants were suffering from major depressive symptoms. We found that 155 (89.1%) of the raped adolescents had major depressive symptoms, indicating that rape had a significant impact on mental health of adolescent girls. This finding is consistent with a longitudinal study finding from Kenya indicating that 85.4% of the sexually abused children in Kenya experienced major depressive symptoms.15 Relatively similar findings with this study were reported elsewhere and revealed that 87%22 and 84.3%23 of rape survivors reported high levels of depressive symptoms, respectively. Another study from a high income country reported that there was a high level of depressive symptoms among raped adolescents.24 This finding suggests that the predominant depressive symptom among raped adolescents is widespread over the globe.

This study revealed that 85 participants (48.9%) had a sexually transmitted disease. This finding was higher than the value indicated by studies done in different parts of Ethiopia: Bahir Dar town among elementary and high school female students, which was 27%,2 Jimma town among adolescents, which was 12.6%,11 Harar among female high school adolescents, which was 28%,1 and Addis Ababa city, which was 55% among street female adolescents.25 The possible reason for higher result of STI in this study is the methodology of the study, ie characteristic of the participants whereby only raped adolescent girls were involved; both studies done in Jimma town, mentioned above, used only clinical symptoms to estimate STI.

In the current study unwanted pregnancy, residency in urban area, assault by hitting and not currently attending school were identified as factors associated with major depressive symptoms. This finding is consistent with findings from Gambia showing that women reporting forced sex and unwanted pregnancy were significantly more likely to suffer from symptoms of depression.26 The possible reasons for high result of major depressive symptoms in those with unwanted pregnancy are that getting pregnant before marriage is socially unacceptable and exposes them to more stress about how to manage the unwanted pregnancy on top of being assaulted. Also most victims (89.7%) were assaulted by a known person, which is a predictive factor for major depressive symptoms in other studies.23,27

The study’s limitation was that there was no comparison group, thus it is unclear how major depressive symptom rates relate to unexposed adolescents. Furthermore, the sample size was small, limiting the generalizability of these findings to all rape-exposed adolescents and resulting in large confidence intervals.

Conclusion

According to the findings, raped adolescents in the study area had a high prevalence of major depressive symptoms and sexually transmitted infections. Efforts to reduce sexual violence against adolescents should be prioritized, and rape victims should be screened and treated as early as possible to avoid mental health problems and other infections. This will benefit their psychological, social, and overall well-being. Furthermore, we found an association between unwanted pregnancy and major depressive symptoms among rape survivors, implying that providing contraceptives to the victim should be considered in conjunction with other treatments. Finally, despite the fact that Ethiopia has a robust legislative and policy framework in place, as well as defined procedures to address sexual violence, rape is said to be widespread. This may be addressed if the country focused on adequate resources and law enforcement, as well as staff skills, competence, and commitment, especially at the local level. Furthermore, the usage of the violence reporting template and clearer alignment with other reporting systems, as well as engaging young people in policy dialogue on sexual violence, plays a pivotal role in rape prevention.

Abbreviations

AOR, adjusted odds ratio; COR, crude odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; GBV, gender-based violence; JUMC, Jimma University Medical Center; WHO, World Health Organization; VAW, violence against women; LMIC low- and middle-income country; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

Ethical clearance was obtained from Jimma University Ethical Review Board and permission to conduct this research was obtained from JUMC. Adolescents' guardians, police staff and adolescents themselves were told about the objectives and benefits of the study. After having obtained written consent and assent from the respondents, the interview was carried out.

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jimma University for funding the study and also the study participants and data collectors.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Benti T, Teferi E. Sexual coercion and associated factors among college female students. J Womens Health Care. 2015;04:2167–2420.

2. Belay HG, Liyeh TM, Tassew HA, et al. Magnitude of gender-based violence and its associated factors among female night students in Bahir Dar City, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Int J Reprod Med. 2021;2021:1–7.

3. Usher A. Sexual violence. Forensic Sci. 1975;5:243–255. doi:10.1016/0300-9432(75)90050-3

4. Oshodi Y, Macharia M, Lachman A, Seedat S. Immediate and long-term mental health outcomes in adolescent female rape survivors. J Interpers Violence. 2020;35:252–267. doi:10.1177/0886260516682522

5. Sifat RI. Sexual violence against women in Bangladesh during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;54:102455. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102455

6. Borumandnia N, Khadembashi N, Tabatabaei M, Alavi Majd H. The prevalence rate of sexual violence worldwide: a trend analysis. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1–7. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09926-5

7. Kaewkiattikun K. Effects of immediate postpartum contraceptive counseling on long-acting reversible contraceptive use in adolescents. Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2017;8:115. doi:10.2147/AHMT.S148434

8. Grose RG, Chen JS, Roof KA, Rachel S, Yount KM. Sexual and reproductive health outcomes of violence against women and girls in lower-income countries: a Review of Reviews. J Sex Res. 2021;58:1–20. doi:10.1080/00224499.2019.1707466

9. Fatusi A, Blum RW. Adolescent health in an international context: the challenge of sexual and reproductive health in sub-Saharan Africa. Adolesc Med State Art Rev. 2009;20:874–86, viii.

10. Kassa GM, Abajobir AA. Prevalence of violence against women in Ethiopia: a Meta-Analysis. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2018;21:624–637. doi:10.1177/1524838018782205

11. Gorfu M, Demsse A. Sexual violence against schoolgirls in Jimma Zone: prevalence, patterns, and consequences. Ethiop J Educ Sci. 2008;2. doi:10.4314/ejesc.v2i2.41983

12. Bekele AB, van Aken MAG, Dubas JS. Sexual violence victimization among female secondary school students in eastern Ethiopia. Violence Vict. 2011;26:608–630. doi:10.1891/0886-6708.26.5.608

13. Ajayi AI, Mudefi E, Owolabi EO. Prevalence and correlates of sexual violence among adolescent girls and young women: findings from a cross-sectional study in a South African university. BMC Womens Health. 2021;21:1–9. doi:10.1186/s12905-021-01445-8

14. Tantu T, Wolka S, Gunta M, et al. Prevalence and determinants of gender-based violence among high school female students in Wolaita Sodo, Ethiopia: an institutionally based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1–9. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-08593-w

15. Mutavi T, Obondo A, Kokonya D, et al. Incidence of depressive symptoms among sexually abused children in Kenya. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2018;12:1–8. doi:10.1186/s13034-018-0247-y

16. Filiatreau LM, Giovenco D, Twine R, et al. Examining the relationship between physical and sexual violence and psychosocial health in young people living with HIV in rural South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020;23. doi:10.1002/jia2.25654

17. Patel R, Gupte SS, Srivastava S, et al. Experience of gender-based violence and its effect on depressive symptoms among Indian adolescent girls: evidence from UDAYA survey. PLoS One. 2021;16:1–18. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0248396

18. Tolu LB, Gudu W. Sexual assault cases at a tertiary referral hospital in urban Ethiopia: one-year retrospective review. PLoS One. 2020;15:1–12. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0243377

19. Amogne MD, Balcha TT, Agardh A. Prevalence and correlates of physical violence and rape among female sex workers in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study with respondent-driven sampling from 11 major towns. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e028247. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028247

20. Jemal J. The child sexual abuse epidemic in Addis Ababa: some reflections on reported incidents, psychosocial consequences and implications. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2012;22:59–66.

21. Bekele I, Zewde W, Neme A. Assessment of prevalence, types and factors associated with adolescent sexual abuse in high school in Limmu Gnet High School. Health Sci J. 2017;11:1–7.

22. Mgoqi-Mbalo N, Zhang M, Ntuli S. Risk factors for PTSD and depression in female survivors of rape. Psychol Trauma. 2017;9:301–308. doi:10.1037/tra0000228

23. Abrahams N, Jewkes R, Mathews S. Depressive symptoms after a sexual assault among women: understanding victim-perpetrator relationships and the role of social perceptions. Afr J Psychiatry. 2013;16:288–293.

24. Khadr S, Clarke V, Wellings K, et al. Mental and sexual health outcomes following sexual assault in adolescents: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2018;2:654–665. doi:10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30202-5

25. Molla M, Ismail S, Kumie A, Kebede F. Sexual violence among female street adolescents in Addis Ababa, April 2000. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2002;16. doi:10.4314/ejhd.v16i2.9802

26. Sherwood JA, Grosso A, Decker MR, et al. Sexual violence against female sex workers in the Gambia: a cross-sectional examination of the associations between victimization and reproductive, sexual and mental health. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1–10. doi:10.1186/s12889-015-1583-y

27. Tarzia L, Thuraisingam S, Novy K, et al. Exploring the relationships between sexual violence, mental health and perpetrator identity: a cross-sectional Australian primary care study. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:1–9. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-6303-y

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.