Back to Journals » Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment » Volume 12

Psychological factors and treatment effectiveness in resistant anxiety disorders in highly comorbid inpatients

Authors Ociskova M , Prasko J , Latalova K , Kamaradova D, Grambal A

Received 15 January 2016

Accepted for publication 31 March 2016

Published 24 June 2016 Volume 2016:12 Pages 1539—1551

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S104301

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Roger Pinder

Marie Ociskova, Jan Prasko, Klara Latalova, Dana Kamaradova, Ales Grambal

Department of Psychiatry, Olomouc University Hospital, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, Palacký University Olomouc, Czech Republic

Background: Anxiety disorders are a group of various mental syndromes that have been related with generally poor treatment response. Several psychological factors may improve or hinder treatment effectiveness. Hope has a direct impact on the effectiveness of psychotherapy. Also, dissociation is a significant factor influencing treatment efficiency in this group of disorders. Development of self-stigma could decrease treatment effectiveness, as well as several temperamental and character traits. The aim of this study was to explore a relationship between selected psychological factors and treatment efficacy in anxiety disorders.

Subjects and methods: A total of 109 inpatients suffering from anxiety disorders with high frequency of comorbidity with depression and/or personality disorder were evaluated at the start of the treatment by the following scales: the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview, the Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness scale, the Adult Dispositional Hope Scale, and the Temperament and Character Inventory – revised. The participants, who sought treatment for anxiety disorders, completed the following scales at the beginning and end of an inpatient-therapy program: Clinical Global Impression (objective and subjective) the Beck Depression Inventory – second edition, the Beck Anxiety Inventory, and the Dissociative Experiences Scale. The treatment consisted of 25 group sessions and five individual sessions of cognitive behavioral therapy or psychodynamic therapy in combination with pharmacotherapy. There was no randomization to the type of group-therapy program.

Results: Greater improvement in psychopathology, assessed by relative change in objective Clinical Global Impression score, was connected with low initial dissociation level, harm avoidance, and self-stigma, and higher amounts of hope and self-directedness. Also, individuals without a comorbid personality disorder improved considerably more than comorbid patients. According to backward-stepwise multiple regression, the best significant predictor of treatment effectiveness was the initial level of self-stigma.

Conclusion: The initial higher levels of self-stigma predict a lower effectiveness of treatment in resistant-anxiety-disorder patients with high comorbidity with depression and/or personality disorder. The results suggest that an increased focus on self-stigma during therapy could lead to better treatment outcomes.

Keywords: anxiety disorders, self-stigma, hope, personality, dissociation, treatment effectiveness

Introduction

Anxiety disorders are highly prevalent mental disorders with the potential to be persistently disabling if not treated.1 Both psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy (PT) have demonstrated their treatment efficacy.2,3 Nevertheless, almost 30%–60% of patients continue to be symptomatic after outpatient management.4–10 There is also a deficiency of studies examining treatment efficacy in hospitalized anxiety-disorder patients. Prasko et al11 published one of the few studies on inpatients and showed that response rates were between 34.3% (in generalized anxiety disorder [GAD]) and 60.1% (in panic disorder) and remission rates between 31.3% (GAD) and 56.5% (panic disorder) in a 6-week inpatient program combining cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and PT. The limited effectiveness of the current methods of treatment has led to an effort to detect aspects that improve treatment success in this population. Such knowledge could lead to an improvement in treatment-effectiveness rates.

Many researchers have focused on sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with good treatment response.12–14 They showed that certain characteristics, such as male sex, unemployment,7 positive history of depression in the family,14 early beginning of the anxiety disorder, greater severity of the disorder,12 or a comorbid personality disorder15,16 often predict poor treatment response.

In the area of psychological factors, dissociation proved to be the significant factor influencing treatment outcome in patients with anxiety disorders.17–19 It has been suggested that the impact on the treatment outcomes of mental disorders may be direct and indirect.17 Dissociation can be understood as a coping strategy to deal with severe anxiety-inducing or painful traumatic experiences.20,21 Dell and O’Neil defined dissociation as a malfunction in the integration of perception, emotions, cognition, memory, or physical responses.22 Dissociation can be experienced by depersonalization, derealization, or amnesia.23 Certain signs of dissociation are apparent in most patients with anxiety disorders.24–26 Dissociation serves to produce detachment from present or expected emotional states of pain, fear, anxiety, or vulnerability.22,27 People who frequently experience dissociation during distress often had neglect or trauma in their past.28,29 Early traumatization is one of the explanations that persons excessively dissociate.30 They furthermore have a tendency to dissociate in partly analogous situations in adulthood. Persons who preferably experience dissociation in coping with difficult situations are disposed to shame and guilt feelings and self-stigma.31

High levels of dissociation are associated with resistance in patients with panic disorder23,32,33 and obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD).18,34,35 Dissociation has been connected with negative outcomes of CBT for anxious inpatients.36 The indirect negative effect of dissociation on treatment effectiveness may stem from insecure attachment patterns, which are commonly found in individuals who excessively dissociate. Insecure individuals may exhibit all sorts of avoidant behavior (especially social avoidance), and this can also limit treatment effectiveness.36

Another characteristic that could influence treatment outcomes is hope. Snyder et al described a complex hope theory based on cognitions, emotions, motivation, and behavior.37 The authors defined hope as “a positive motivational state that is based on an interactively derived sense of successful 1) agency (goal-directed energy) and 2) pathway thinking (planning to meet goals)”.37 What sets hope apart from similar concepts, such as optimism, is the emphasis on the individual’s activity to reach the goals.36 Fundamental elements of hope, agency, and pathway thinking are closely related to one another.38 Higher rates of hope, as understood by Snyder et al, are connected to lower depressive symptoms.39 In the field of psychotherapy, hope has been empirically found to increase efficacy.29,37,40–46 It has been implemented as a part of positive psychotherapy47 and included in more traditional treatments, such as CBT.42,48

Levels of hope also predict the use of specific coping strategies and could have a direct impact on the efficacy of the psychotherapy.37 Kwon has shown that individuals with low hope prefer avoidant behavior when dealing with stress.49 Conversely, hopeful persons practice more adaptive strategies of coping, such as active search for the solution of the problem, careful planning, seeking social support, or using humor to defuse destabilizing negative emotions. Their ability to cope effectively with distress can explain the positive impact of the patient’s hopeful mental state on the efficacy of psychotherapy.37

Another important psychological factor influencing the efficiency of treatment of mental disorders could be self-stigma.50–52 Public attitudes toward persons suffering from psychiatric problems have been a cause of their unequal status in society for centuries. Prejudices, which are connected to mental illness stigma, may lead to direct discrimination against patients with psychiatric diagnoses. More subtle manifestations of rejection, such as defamation or subtle exclusion from society, are also common.53,54 Self-stigma (internalized stigma) is a condition in which individuals with stigmatizing problems (such as mental disorders) accept social prejudices about psychiatric patients and apply them to themselves.55 It has been postulated that only patients with severe psychiatric illnesses were likely to be the objects of stigma.56 Nevertheless, Alonso et al57 found that patients with anxiety disorders can be labeled as well. Ritsher and Phelan58 recognized that stigma brings greatest harm in patients who internalize it. It leads to poor quality of life,59 lack of adherence to treatment,50,60–62 or increased suicidality.63

Self-stigma manifests itself primarily at the intrapsychic level. It affects self-concept, attitudes toward other people, and expectations of the future. The development of self-stigma often leads to a decrease in self-confidence and self-esteem and a growth of feelings of hopelessness and pessimism.55,64 Through these negative consequences, self-stigma may affect the success of treatment of mental disorders. Individuals who struggle with self-stigma also tend to avoid psychiatric or psychological treatment altogether, because of the fear of being stigmatized.52 Therefore, they completely avoid or delay seeking help or beginning treatment.65,66 Investigators have mainly focused on the stigmatization and self-stigma of individuals with psychoses,50,67 mood disorders,67 or alcohol dependence.68 However, stigma also occurs in relatively less severe but more widespread mental disorders, such as anxiety disorders.57 People suffering from a higher self-stigma level more frequently disregard the physician’s instructions about medication and prematurely discontinue it.60,69 This association of adherence and self-stigma has been confirmed in patients with anxiety disorders,60 schizophrenia,50 bipolar disorder,62 and depression.70 Nevertheless, not all patients with psychiatric disorders suffer from high levels of self-stigmatization. Some do not experience it, even if they are faced with discrimination. It is possible that there are individuals who are more resistant to the internalizing of stigma than others.71

The relationship between treatment effectiveness and personality traits from the Cloninger theory of personality (specifically, harm avoidance and self-directedness) has been studied in different populations, such as individuals with OCD,72 bulimia nervosa,73 and depression.74 It was shown that the harm-avoidance trait lowered antidepressant efficacy in depression.74 On the other hand, higher levels of self-directedness may lead to better treatment outcomes in some populations.72,73 Harm avoidance is usually elevated in patients with anxiety disorders,75,76 and self-directedness is often decreased.35,36

As for these personality traits, Margetić et al77 discovered that one of the most substantial characteristics accompanying self-stigma is harm avoidance.77 This is a trait that comprises features such as anticipation worry, fatigability, shyness, and difficulties in handling ambiguous situations. It offers a heritable predisposition to strong responses to negative stimuli and learning to the avoidance of punishment.78 Harm avoidance could be a feature that is connected with the increasing probability of internalizing self-stigma.77 The other important personality characteristic linked with self-stigma is self-directedness.77 Self directedness can help, as a protecting aspect, impede the internalization of self-stigma. Persons with higher levels of this characteristic are purposeful, responsible, and resourceful.79 Such features create an individual who is self-regulating, independent, and less vulnerable to decreased hope in stressful periods.77 However, the influence of these personality traits on treatment success in anxiety disorders has not been explored yet.

The aim of our study was to investigate the relationship between self-stigma and the treatment efficiency of anxiety disorders. The main hypothesis was that anxiety-disorder patients who have a higher degree of self-stigma display fewer changes during treatment. This hypothesis is based on Livingston and Boyd’s meta-analysis findings56 and the results of Yanos et al50 and Fung et al.52 The strength of this expected influence was also an important issue. Although self-stigma could show to be a significant predictor of therapeutic change, it still would not show how strong it really is. This is why other factors came into the equation. Various clinical, sociodemographic, and personality aspects that were previously associated with self-stigma and/or treatment effectiveness of the chosen disorders were included to serve for comparison of the predicted impact.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

Involvement in the investigation was offered to all hospitalized individuals undergoing complex treatment of anxiety disorders at the psychotherapeutic department of the Department of Psychiatry in Olomouc University Hospital. Data were collected from November 2012 to November 2014. Of the 442 persons admitted to the psychotherapy unit in a given period, anxiety disorder at baseline was diagnosed in 184 patients. These patients were resistant to outpatient pharmacological and psychotherapeutic treatment (ie, they were chronically unresponsive to standard outpatient pharmacological and/or psychological treatment). Because of this resistance, they were indicated for complex inpatient treatment.

Inclusion criteria for the study were age 18–75 years and a diagnosis of anxiety disorder according to the criteria of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 (panic disorder with/without agoraphobia, GAD, social phobia, or mixed anxiety–depressive disorder), and exclusion criteria were organic mental illness, psychoses, current substance-use disorders, or an antisocial personality disorder, and significant suicidal tendencies.

A total of 145 patients agreed to participate, filled in the informed consent, and completed several scales and questionnaires. There were 36 dropouts for the following reasons: eleven patients discontinued treatment, one lady was unable to attend due to partial illiteracy, and 24 subjects were rediagnosed and lost criteria for inclusion in the study. Therefore, 109 patients completed the study and were calculated in most analyses. There were no differences between patients who participated or dropped out from the study of demographic features.

The majority of the patients were women (n=73, 66.9%), with a mean age of 40.0±12.1 years. Most participants were students or employed (56.9%). Others were unemployed (22.9%) or receiving a disability allowance or old-age pension (20.2%). Highest education attained was secondary school for 46.8%, lower vocational training for 27.5%, primary school for 12.8%, and university for 12.8%. With regard to marital status, 36.7% of patients were single and 35.8% married. The rest were divorced (21.1%) or widowed (6.4%).

Diagnosis was determined by an outpatient psychiatrist, a psychiatrist of the department, and a senior psychiatrist. The diagnoses were further confirmed by the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI)80 implemented by a psychologist. The number of patients diagnosed with each anxiety disorder is in Table 1.

| Table 1 Primary diagnoses and comorbidities |

Some comorbid disorder was present in 96 individuals. A total of 32 patients (29.4%) were diagnosed with comorbid depression, and 31 participants (28.4%) struggled with a comorbid personality disorder. Borderline personality disorder was the most frequent personality disorder (19.3%). Another anxiety disorder was present in 25 patients (22.9%).

The mean duration of the anxiety disorder was 8.5±8.1 years, with average age at onset of the disorder 31.1±14.4 years. The length of the personality disorders (in comorbid cases) was impossible to find out. Patients described the history of their anxiety disorder in their own words. According to these data, the comorbidity of a personality disorder was not recognized by the patients usually. In cases of a comorbid mild depressive disorder, the symptoms of depression often developed secondarily to the anxiety symptoms. The mean number of previously undergone psychiatric hospitalizations was 2.1±1.5. Before the current hospitalization, the patients were treated for their anxiety disorder and depression (in comorbid cases) at outpatient facilities, mostly by drug therapy alone and by psychotherapy rarely. The each reason for hospitalization was the lack of efficacy in the outpatient treatment.

The patients from the two treatment groups (CBT, n=45; PT, n=64) did not significantly differ in sex, age, or education. They were also comparable in levels of anxiety (Beck Anxiety Inventory [BAI] 23.8±12.7 or 26.0±12.2, respectively; unpaired t-test, not significant) in the beginning and objective assessment of Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI) (CGI – objective version (CGIObj); 4.4±1.12 or 4.3±1.09, respectively; unpaired t-test, not significant).

Measurements

All patients filled in several scales and questionnaires that were offered by a researcher who was not a clinical worker of the department. The same person also assessed the evaluative MINI.80 The following methods were finalized at the beginning of the program.

The MINI is a structured interview covering diagnostic criteria for common mental disorders according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-IV and ICD-10.80 Interrater reliability was 0.75 or higher in all parts of the diagnostic interview, except the less reliable current manic episode.81

The Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI) scale measures the level of self-stigma in adults with diagnosed mental disorders.82 It includes 29 items divided into five subscales: alienation, stereotype endorsement, discrimination experience, social withdrawal, and stigma resistance. Patients mark one number from a 4-point Likert scale according to their level of agreement with each statement.82 Cronbach’s α for the method is excellent (α=0.9). The Czech version of the scale has an equivalent internal consistency (α=0.91).83

The Adult Dispositional Hope Scale (ADHS) is grounded on the theory of hope created by Snyder et al.37 It consists of 12 items divided into three parts: four items measure pathway thinking (ie, an ability to identify adaptive ways to achieve goals), four items focus on agency (ie, inner motivation or energy to pursue goals and remain motivated even when obstacles occur), and four items are distractors (they are not analyzed). Participants choose a number from an 8-point Likert scale in accordance with their level of agreement or disagreement with each statement. Cronbach’s α for this scale is good (α=0.74–0.84).37 Cronbach’s α for the Czech version of the scale is also good (α=0.82 for the general population, α=0.85 for the psychiatric population).84

The Temperament and Character Inventory – revised (TCI-R) measures personality according to the biosocial theory of Cloninger.85,86 It consists of 240 items that are divided into four traits of temperament (novelty seeking, harm avoidance, reward dependence, and persistence) and three traits of character (self-directedness, cooperativeness, and self-transcendence).87 Individuals respond to the statements by using a 5-point Likert scale based on their degree of agreement or disagreement with them. The internal consistency in the English version of the inventory seems satisfactory (α-values ranging from 0.58 of the pure-hearted conscience facet of cooperativeness to 0.9 of the spiritual acceptance facet of self-transcendence, with most α-values being 0.7–0.9).86,88 The reliability of the Czech translation of the method is also satisfactory.87 In our sample, the α-values of the six scales exceeded 0.7, with persistence reaching the highest levels (α=0.91). The α-value of the seventh scale, novelty-seeking, was only 0.54. The most important scales in this study – harm avoidance and self-directedness – had acceptable inner consistency (α=0.81 and 0.71, respectively).

Several scales and questionnaires were completed at the beginning and the end of the program. The CGI is a 7-point scale that evaluates the overall level of psychopathology.89 Every point of the scale has its defined unique characteristics. It may be completed by a physician (CGIObj) or a patient (CGI – subjective version [CGISubj]). Intraclass correlations lie in the interval 0.88–0.92.90

The BAI91 measures the intensity and frequency of the anxiety symptoms experienced during the last week. Responses are based on a 4-point Likert scale.91 The method has excellent internal consistency (mean α=0.91).92 Cronbach’s α for the Czech version of the scale is 0.92.93

The Beck Depression Inventory – second edition comprises 21 depressive symptoms.94 Patients choose which symptoms they perceived in the last 2 weeks and how intense they were.95 The internal consistency of the scale is higher in the psychiatric population (α=0.86) than in the general population (α=0.81).94 The Czech version was validated by Preiss and Vacir; Cronbach’s α reached 0.89.96

The Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES) assesses the intensity of dissociative experiences in both the psychiatric and general populations.97 The scale describes 28 kinds of dissociative symptoms. Participants mark a spot on a 10 cm line according to the percentage of time that they experience the symptoms. Apart from the general level of perceived dissociative experiences, it is possible to compute a score of pathologic dissociation (DES Taxon [DES-T]). Pathologic dissociation consists of more extreme experiences of dissociative amnesia, derealization, depersonalization, or identity alternation.98 Cronbach’s α for the DES is excellent (α=0.96).97 The Czech translation showed psychometric properties equal to the original version of the scale.99

Methods of treatment

All patients were treated for six weeks in the inpatient group psychotherapeutic program of the Department of Psychiatry of Olomouc University Hospital. The treatment was uniform for all patients: focused mostly on the anxiety disorder, but both various antidepressants and CBT strategies were also helpful for the comorbid depressive symptoms and personality issues. The program included 25 group sessions and five individual sessions of CBT or psychodynamic therapy in combination with PT. The CBT program consisted of standard steps covering psychoeducation, case conceptualization, making a list of symptoms and life problems, cognitive restructuring, exposure therapy, elaboration of core beliefs and conditional rules, and problem solving. A short psychodynamic program focused on relationship difficulties in patients’ lives, interactions in the group, and developmental issues. Both psychotherapeutic programs were supervised once a week by an experienced therapist. The program was completed by social skills practice and sport.11 There was no randomization to the type of group-therapy program. Apart from the group and individual sessions, the psychotherapeutic group program consisted of additional supporting activities: progressive muscle relaxation and sport. The patients were treated with standard doses of previously used antidepressants. Only minimal changes in doses were done. The psychotherapeutic and pharmacological strategies agreed with the Czech national guidelines for the treatment of psychiatric patients.100,101

Medication

The most common medication at the start of the treatment was antidepressants (n=97, 89%). The average dose was 47.5±31.24 mg of paroxetine equivalent. Forty patients (36.7%) initially used benzodiazepines at an average dose of 0.67±0.82 mg of alprazolam equivalent. Some participants (n=28, 25.7%) were also taking antipsychotics at a mean dose of 1.31±1.23 mg of risperidone equivalent.

The average dosages of medication at the termination of the program were similar to those at the start of the hospitalization. The average dose of antidepressant was 41.32±27.9 mg of paroxetine equivalent. The mean dose of anxiolytics was 0.49±0.44 mg of alprazolam equivalent, and the average dose of antipsychotics was 1.28±0.91 mg of risperidone equivalent. The differences between initial and final average doses of medication were insignificant (antidepressants, Mann–Whitney U=4,520, not significant; anxiolytics, Mann–Whitney U=303.5, not significant; antipsychotics, paired t-test, t=0.5436, df=62, not significant).

Rating-scale changes

The average scores for all measures assessing disorder severity significantly decreased after treatment (Table 2). There was a substantial decrease in the general severity of the disorder during the therapy (CGISubj and CGIObj). This decrease can be described as large (Cohen’s d for CGISubj was 0.83 and for CGIObj 2.4). There was also a substantial decrease in the total scores of anxiety and depression (BAI and Beck Depression Inventory, Table 2). The patients showed a higher decrease of symptoms of depression, where the difference was medium (d=0.66), than in reduction of anxiety, where the difference between the first and last measurement was small (d=0.28).

A total of 52 patients achieved remission, defined as a final CGIObj rating of 1 or 2 (47.7%). A smaller group (30.3%) of individuals showed mild symptoms of mental disorders at the end of the hospitalization (n=33, CGIObj 3). The rest of the participants (n=24, 22%) suffered from moderate or severe symptoms of mental disorders at the end of the treatment (CGIObj 4 or higher).

Statistics

Statistics were calculated using GraphPad Prism 5.0 and SPSS 17. Descriptive statistics were applied to calculation of the demographic data, mean scores of scales and questionnaires, and to calculate the character of data distribution. Between-group differences were calculated by t-tests for paired samples (for medication dosages and rating-scale scores at the beginning and at the completion of the treatment) or independent t-tests (for types of group therapy and comorbidities) or their nonparametric equivalents and one-way analysis of variance (for three major diagnostic groups). Tukey’s range test or Dunn’s multiple-comparison tests were applied as corrections to the analysis-of-variance measurements. The difference between the first and last measurements of BAI and CGIObj was also analyzed by applying the relative-change calculation. Correlations between variables were examined by Pearson’s or Spearman’s correlation coefficient and backward-stepwise multiple regression. Bonferroni correction was added to the regression to lower the probability of false-positive results. The effect size of the multiple linear regression analysis was calculated by using the f2 indicator or its equivalents. The statistical significance threshold was set at 5%.

The local ethical committee of Olomouc University Hospital approved the investigation and study. All patients signed an informed consent to take part in the study. The research was done in accordance with the recent version of the Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice and the Helsinki Declaration.102

Results

Therapeutic change and demographic, clinical, and psychological factors

The relative change in psychopathology assessed by physicians using CGIObj did not significantly correlate with any of the demographic factors, ie, age at the onset of the disorder, current age, duration of the psychiatric disorder, number of previous hospitalizations, indices of psychopharmaceuticals, and the severity of psychopathology measured at the start of the treatment (Table 3).

However, the objective change in psychopathology measured by the relative-change CGIObj significantly correlated with the initial levels of dissociation (DES), pathological dissociation (DES-T), self-stigma (ISMI), hope (ADHS), and the personality traits (TCI-R) of harm avoidance and self-directedness (Table 4).

There were no statistically significant differences between the relative changes among subgroups of patients divided according to the primary anxiety disorder (panic disorder/agoraphobia versus social phobia versus GAD/mixed anxiety–depressive disorder, subgroups with or without comorbid depression or with or without comorbid anxiety disorder) (Table 4).

However, there were differences in relative changes in CGIObj between the subgroups with and without a comorbid personality disorder (Table 4). Patients who did not have a comorbid personality disorder improved significantly more in their overall mental state than participants who had a comorbid personality disorder. The magnitude of this difference was medium (d=0.66).

Relative change in BAI

The relative change in anxiety according to subjective BAI score did not significantly correlate with any factor but the initial level of self-stigma (Spearman’s ρ=0.26, P<0.01) (Table 4).

Backward-stepwise multiple-regression analysis

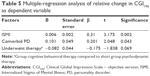

A backward-stepwise multiple-regression analysis was performed to detect the most significant factors influencing treatment effectiveness, assessed with CGIObj. The dependent variable was the relative change in CGIObj during treatment. The independent factors were comorbidity with a personality disorder, indicator of having or not having a partner, undergoing group CBT or short psychodynamic therapy, initial severity of the symptoms of dissociation (DES), and the starting levels of self-stigma (ISMI), hope (ADHS), harm avoidance (TCI-R), and self-directedness (TCI-R). All of these regressors were previously significantly connected with the dependent variable.

The subsequent model explained 16.1% of the dependent variable (P<0.001, Table 5). The effect size for the model was medium (f2=0.23). The predictors were removed in single steps: self-directedness, followed by dissociation, hope, harm-avoidance, and partnership were eliminated at first. The type of group therapy, the initial level of self-stigma, and comorbid personality disorders remained to the last step of the regression. After the Bonferroni correction, the adjusted P-value was 0.0063. Therefore, self-stigma remained as the only significant predictor of relative change measured by the physician during the treatment.

Discussion

The aim of this investigation was to find potential psychological factors related to treatment response in patients with anxiety disorders treated with CBT or PT. Patients ratings on all scales reduced during treatment. The improvement in symptomatology is encouraging, in light of the fact that these patients had been resistant to previous outpatient treatment. There were more substantial changes in signs of depression and general psychopathology than in anxiety. The explanation of these results is not easy, and we can only speculate.

While most patients improved in anxiety symptoms, the improvement was small. This may have been because of the therapeutic program: part of the therapy was daily exposure to feared situations. In fact, the patients in intensive psychotherapeutic program improved more in avoidant behavior than in general symptoms of anxiety. Therefore, the patients were learning how not to avoid their fears, and while doing so, they were anxious because they were actually exposed to the unpleasant stimuli. They usually underwent this part of the treatment until the last day of their hospitalization. Therefore, they did not have much time to feel relaxed. The intensive therapeutic program is quite demanding.

This hypothesis could be supported by comparable outcomes detected in a study of patients suffering from social phobia.103 In this study, the ratings on the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale avoidance subscale decreased much more quickly than the anxiety subscale and the BAI. Also, Başoğlu et al found that global improvement relied more on improvement in avoidant behavior than on decrease in panic or anticipatory anxiety in the therapy of patients with panic disorder with agoraphobia.104 Another possibility is that the current results reflect findings for individuals with sets of comorbidities. Another explanation offers another characteristic of the program: the treatment was inpatient. It may be that the mean levels of anxiety increased at the end of the treatment because of the anticipatory anxiety in the patients. They were coming home and back to the job, and may have apprehended this step.

No sociodemographic factor significantly correlated with the therapeutic change. Livingston and Boyd conducted a meta-analysis of the existing state of evidence about self-stigma in psychiatric patients.56 The authors concluded that demographic factors did not play a major role as factors modulating the likelihood of the manifestation of self-stigma. The current results suggest that there are no substantial differences in the degree of self-stigma in patients with different education, ethnicity, sex, occupation, or income.56 Also, Watson et al failed to recognize any substantial connection between self-stigma and several demographic aspects.19

The only demographic aspect that might be importantly associated with self-stigma is the patient’s age. Despite the fact that most articles analyzed by Livingston and Boyd showed that there was no significant association between self-stigma and age, a small number of investigations found one.56 However, these outcomes were not robust, and as Livingston and Boyd concluded,56 may be omitted. The results of research concentrated on self-stigma in bipolar affective disorder,62 psychoses,61 and anxiety disorders19,60 indicated that age did not affect the degree of self-stigma significantly. Therefore, the outcomes of these studies indicate that demographic features do not play a significant role in determining self-stigma. This is in accordance with our results.

This is contrary to other studies that found some sociodemographic factors predicting therapeutic outcome in selected anxiety disorders.105,106 Predictors of the response to treatment using both CBT and PT in patients suffering from social phobia were summarized in the work of Mululo et al.12 This article condensed outcomes of 24 studies. Age of disorder onset, disorder severity, existence of comorbid anxiety disorders, and low expectations from therapy were identified as significant predictors of therapeutic response. However, we did not measure therapeutic expectations. In our previous study in individuals suffering from social phobia, changes in the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale positively correlated with disorder-onset age.106 Different study populations could explain the differences between the results of the studies mentioned and those of the current study.

It is uncertain if the present outcomes reflect findings for anxiety samples alone or for a set of comorbidities, but comorbidity with depression did not appear to be an aspect contributing to treatment effectiveness in the present study. This outcome is reinforced by Steketee et al,107 who presented comparable outcomes in OCD patients. On the other side, it is not consistent with the results of Overbeek et al,108 in which the depressive disorder comorbidity predicted enhanced treatment results in OCD patients. The opposite outcome was also found by Van Ameringen et al.105 In their study, higher levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms before treatment were linked to increased resistance to pharmacological treatment in social phobia. Also, Heldt et al4 showed worse treatment response in panic disorder comorbid with depression. These different results could be attributable to various study populations and different treatment methods. Finally, another study on an inpatient therapeutic program for anxiety disorders showed that treatment effectiveness of intensive therapeutic programs for anxiety disorders was predicted by the level of depression, comorbidity with depression, personality disorders, and marital status.11

Another important factor that influenced therapeutic change was comorbidity with a personality disorder. Patients without personality-disorder comorbidity improved substantially more in the course of the therapy when compared to patients with personality-disorder comorbidities. Some studies furthermore described worse treatment outcomes in patients suffering from anxiety disorder and comorbid personality disorder. Telch et al109 recognized that individuals with panic disorder and a comorbid cluster C personality disorder improved significantly less in the course of psychotherapy than patients without comorbidity. Thiel et al,110 partially reinforced by Steketee et al,107 indicated that psychotherapy for OCD was significantly less efficient when patients suffered from a comorbid schizotypal or narcissistic personality disorder. The presence of comorbid personality disorders was linked to resistance to pharmacological treatment of social phobia.107 In a study by Prasko et al,111 there was a less significant decrease in specific panic and agoraphobic symptoms in patients with a comorbid personality disorder than in patients without a personality disorder. Also, Vyskocilova et al112 found that social phobia patients with a comorbidity of personality disorder displayed a smaller reduction of symptoms during therapy than patients with social phobia without comorbidity.

On the other hand, in a social phobia study of Kamaradova et al, there were no differences in treatment efficacy of a complex therapeutic program (PT and psychotherapy) between patients with comorbid personality disorder and patients without personality disorders.106 Also, another study with a larger number of study subjects showed that treatment effectiveness of an intensive psychotherapeutic program for anxiety disorders was predicted by comorbidity with personality disorders.11

Our current data suggest that the level of dissociation measured by DES and pathological dissociation measured by DES-T significantly correlates with poorer treatment outcome. However, this factor failed to retain statistical significance during backward-stepwise regression, because other factors were more influential. The connection between higher dissociation and lower treatment effectiveness was also found in other studies with different diagnostic populations. It has been repeatedly shown that dissociation is one of the factors contributing to poor treatment outcome in panic disorder23,24,32 and OCD patients.18,113 In our previous work, dissociation was an important factor influencing treatment effectiveness in anxiety disorders.19

Snyder et al presumed that hope is a sense developing in certain circumstances in goal-directed situations.37 In the framework of the intensive inpatient-psychotherapy program, the more the patients knew, what they wanted to realize in the course of the hospitalization, and were motivated and active, the more efficient the treatment was. Still, our study seems to be the first that shows that hope may be a significant predictor of effectiveness in anxiety-disorder treatment.

Although there have been several studies focusing on the relationship between self-stigma and treatment effectiveness, they were mostly related to PT and affective disorders and psychoses.50,52,70 The influence of self-stigma on the treatment effectiveness of systematic psychotherapy has not been recognized. The moderators of this relationship could have been the demoralization brought on by depressive symptoms, as well as the lack of agency caused by low levels of hope, a factor that is also connected with depressive symptoms.82 Therefore, one of the objectives of this research was to determine if self-stigma contributes considerably to the treatment efficiency of systematic therapy for anxiety disorders. As for the impact of self-stigma on combined pharmacological and psychotherapeutic effectiveness, we found an inverse relationship. The strong correlation between internalized stigma and the change in mental state during treatment, evaluated by a psychiatrist, supports the hypothesis that patients who highly stigmatize themselves improve noticeably less during systematic treatment than patients with lower levels of internalized stigma. Also, it has been confirmed that the more that individuals agree with prejudices about psychiatric patients and apply these to themselves, the less they improve in their anxiety symptoms.

Temperament and character traits from Cloninger’s biosocial theory of personality can influence the therapeutic efficacy of anxiety disorders.86 The objective change in global severity of the disorder significantly negatively correlated with harm avoidance and positively with self-directedness. For most patients suffering from anxiety disorder, the core symptoms are anxiety and avoidant behavior, which can be linked mostly to the harm-avoidance trait. Self-directedness is the character trait linked to achieving goals and planning.86 The results replicate the findings of other studies on different patient samples and seem to be the first of their kind in patients with anxiety disorders.72–74 Harm avoidance and self-directedness have both been recognized as features influencing efficiency of PT and psychotherapy. Curiously, these two traits have also been identified as typically lower (in self-directedness) and higher (in harm avoidance) among persons with anxiety disorders in comparison with the general population. Also, these two personality traits have been identified to be most significantly connected to self-stigma (harm avoidance tends to be higher and self-directedness lower in patients who suffer from self-stigma). The other five personality traits of Cloninger’s theory of personality relate only slightly or not at all to treatment effectiveness, self-stigma, and anxiety disorders.

We wanted to find whether self-stigma is a strong predictor of therapeutic change or if it would be eliminated during regression analyses because other factors would be stronger. It might be the case that harm avoidance would be better suited to explain the lack of the treatment changes. After all, it is claimed to be temperamental, a largely heritable trait, and self-stigma is learned during life. However, self-stigma was stronger. With regard to the results of backward-stepwise multiple-regression analysis and after Bonferroni correction, self-stigma was the only significant factor that influenced relative treatment change. Other factors, which were separately associated with treatment response, were eliminated.

Limitations

The study has several limitations. The group of participating patients was relatively small and heterogeneous, with a high level of comorbidity with other anxiety disorders, depression, or personality disorder. They were also not sufficiently responsive to the outpatient treatment. On the other hand, there was a relatively unselected “real” patient sample, very typical for the patients with anxiety disorders referred to psychiatric hospitalization. Such a population was described in our other study.11 This fact decreased the possibility of generalizing the results to the whole population of patients with anxiety disorders or to particular subgroups of this population, which are usually treated in outpatient conditions. Other investigations grounded on the bigger population of patients with more specific anxiety disorders need to be carried out. Furthermore, in these studies, scales developed for the assessment of the specific anxiety-disorder symptoms should be used rather than the general BAI. Another limitation may have been the use of psychodiagnostic methods built on self-evaluation. The use of these inventories and scales is determined by the ability of introspection of the patients and their preparedness to be open in the statements.

Another limitation was that individuals were largely highly functioning (ie, had jobs and/or were studying). This could also limit generalization of our results. It should also be mentioned that specific diagnostic groups might respond to intensive management differently. The patients were treated with various drugs and with two alternative psychotherapeutic approaches. Still, despite this diagnostic and treatment diversity, self-stigma and comorbid personality disorders proved to be important factors affecting treatment effectiveness in patients with anxiety disorders.

With regard to the comparison of changes according to treatment program, there was a critical limitation: the patients were not randomized, and there was a selection bias. Therefore, it is not possible to generalize this finding. However, the treatment approach could have been a variable that could influence a change in therapy, so it seemed important to include it in the analysis. CBT showed statistically significant superiority over PT with regard to improvement in overall mental state measured with CGIObj (Table 4).

Conclusion

Some patients with anxiety disorders adopt social stigmatizing stereotypes and apply them to themselves. A comorbid personality disorder and a higher level of self-stigma may predict lower treatment effectiveness in anxiety disorders at the start of treatment. The outcomes of this study should be confirmed in other samples and ideally lead to the selection of optimal therapeutic approaches for specific patients.

Acknowledgments

We thank the health care professionals who provided treatment during the research. Namely, we thank the psychiatrist of the department, Zuzana Sigmundova, for securing high-quality psychiatric diagnostics and the group CBT. We also want to acknowledge the work of the psychologists of the department, Snezana Cakirpaloglu and Petra Kasalova, who were running the short psychodynamic group therapies. Last, but not least, we thank the nurses under the leadership of the ward nurse Hana Pizurova, who took care of part of the data collection and secured additional treatments.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. | ||

Hooke GR, Page AC. Predicting outcomes of group cognitive behavior therapy for patients with affective and neurotic disorders. Behav Modif. 2006;26:648–659. | ||

Pohl RB, Feltner DE, Fieve RR, Pande AC. Efficacy of pregabalin in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison of BID versus TID dosing. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;25:151–158. | ||

Heldt E, Manfro GG, Kipper L, et al. Treating medication-resistant panic disorder: predictors and outcome of cognitive-behavior therapy in a Brazilian public hospital. Psychother Psychosom. 2003;72:43–48. | ||

Tyrer P, Seivewright H, Johnson T. The Nottingham study of neurotic disorder: predictors of 12-year outcome of dysthymic, panic, and generalized anxiety disorder. Psychol Med. 2004;34:1385–1394. | ||

Linden M, Zubraegel D, Baer T, Franke U, Schlattmann P. Efficacy of cognitive behaviour therapy in generalized anxiety disorders: results of a controlled clinical trial (Berlin CBT-GAD study). Psychother Psychosom. 2005;74:36–42. | ||

National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK). Generalized Anxiety Disorder in Adults: Management in Primary, Secondary, and Community Care. Leicester (UK): British Psychological Society; 2011. | ||

Zou C, Ding X, Flaherty JH, Dong B. Clinical efficacy and safety of fluoxetine in generalized anxiety disorder in Chinese patients. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:1661–1670. | ||

Pelissolo A. [Efficacy and tolerability of escitalopram in anxiety disorders: a review]. Encephale. 2008;34:400–408. French. | ||

Katzman MA, Bleau P, Blier P, et al. Canadian clinical practice guidelines for the management of anxiety, posttraumatic stress, and obsessive-compulsive disorders. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14 Suppl 1:S1. | ||

Prasko J, Kamaradova D, Cakirpaloglu S, et al. Predicting the therapeutic response to intensive psychotherapeutic programs in patients with neurotic spectrum disorders. Act Nerv Super Rediviva. 2015;57:30–39. | ||

Mululo SC, Menezes GB, Vigne P, Fontenelle LF. A review on predictors of treatment outcome in social anxiety disorder. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2012;34:92–100. | ||

Schat A, van Noorden MS, Noom MJ, et al. Predictors of outcome in outpatients with anxiety disorders: the Leiden routine outcome monitoring study. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47:1876–1885. | ||

El Alaoui S, Ljótsson B, Hedman E, et al. Predictors of symptomatic change and adherence in internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for social anxiety disorder in routine psychiatric care. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0124258. | ||

Mennin DS, Heimberg RG. The impact of comorbid mood and personality disorders in the cognitive-behavioral treatment of panic disorder. Clin Psychol Rev. 2000;20:339–357. | ||

Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, Reich DB, Silk KR. Axis I comorbidity in patients with borderline personality disorder: 6-year follow-up and prediction of time to remission. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:2108–2114. | ||

Prasko J, Raszka M, Adamcova K, et al. Predicting the therapeutic response to cognitive behavioural therapy in patients with pharmacoresistant obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2009;30:615–623. | ||

Ociskova M, Prasko J, Kamaradova D, Grambal A, Latalova K, Sigmundova Z. The relationship between internalized stigma and treatment efficacy in the mixed neurotic spectrum and depressive disorders. Neuroendocrinol Lett. 2014;35:711–717. | ||

Watson S, Chilton R, Fairchild H, Whewell P. Association between childhood trauma and dissociation among patients with borderline personality disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40:478–481. | ||

Ross CA. Borderline personality disorder and dissociation. J Trauma Dissociation. 2007;8:71–80. | ||

Dell PF, O’Neil JA. Dissociation and the Dissociative Disorders: DSM-V and Beyond. New York: Routledge; 2009. | ||

Bob P. [Dissociative symptoms and their measurement]. Ceska Slov Psychiatr. 2000;6:301–309. Czech. | ||

Gulsun M, Doruk A, Uzun O, Turkbay T, Ozsahin A. Effect of dissociative experiences on drug treatment of panic disorder. Clin Drug Investig. 2007;27:583–590. | ||

Pastucha P, Prasko J, Grambal A, et al. Panic disorder and dissociation: comparison with healthy controls. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2009;30:774–778. | ||

Prasko J, Raszka M, Diveky T, et al. Obsessive compulsive disorder and dissociation: comparison with healthy controls. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2010;154:179–183. | ||

Bremner JD, Brett E. Trauma-related dissociative states and long-term psychopathology in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 1997;10:37–49. | ||

Zlotnick C, Shea MT, Pearlstein T, Simpson E, Costello E, Begin A. The relationship between dissociative symptoms, alexithymia, impulsivity, sexual abuse, and self-mutilation. Compr Psychiatry. 1996;37:12–16. | ||

Irving LM, Snyder CR, Cheavens J, et al. The relationship between hope and outcomes at the pretreatment, beginning, and later phases of psychotherapy. J Psychother Integr. 2004;14:419–443. | ||

Rugens A, Terhune DB. Guilt by dissociation: guilt primes augment the relationship between dissociative tendencies and state dissociation. Psychiatry Res. 2013;206:114–116. | ||

Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annu Rev Sociol. 2001;27:363–385. | ||

Ball S, Robinson A, Shekhar A, Walsh K. Dissociative symptoms in panic disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1997;185:755–760. | ||

Seguí J, Márquez M, García L, Canet J, Salvador-Carulla L, Ortiz M. Depersonalization in panic disorder: a clinical study. Compr Psychiatry. 2000;41:172–178. | ||

Praško J, Raszka M, Adamcová K, Kopřivová J, Kudrnovská H, Vyskočilová J. [Prediction of therapeutic response in patients suffering from obsessive compulsive disorder resistant to the treatment with psychopharmacs]. Psychiatrie (Stuttg). 2008;12 Suppl 3:55–62. Czech. | ||

Raszka M, Praško J, Adamcová K, Kopřivová J, Vyskočilová J. [Dissociation and cognitive function in obsessive compulsive disorder: cross sectional study]. Ceska Slov Psychiatr. 2008;104:298–296. Czech. | ||

Spitzer C, Barnow S, Freyberger HJ, Grabe HJ. Dissociation predicts symptom-related treatment outcome in short-term inpatient psychotherapy. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2007;41:682–687. | ||

Snyder CR. Handbook of Hope: Theory, Measures, and Applications. San Diego: Academic Press; 2000. | ||

Snyder CR, Sympson SC, Ybasco FC, Borders TF, Babyak MA, Higgins RL. Development and validation of the State Hope Scale. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;70:321–335. | ||

Snyder CR, Harris C, Anderson JR, et al. The will and the ways: development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;60:570–585. | ||

Snyder CR, Hoza B, Pelham WE, et al. The development and validation of the Children’s Hope Scale. J Pediatr Psychol. 1997;22:399–421. | ||

Mathis GM, Ferrari JR, Groh DR, Jason LA. Hope and substance abuse recovery: the impact of agency and pathways within an abstinent communal-living setting. J Groups Addict Recover. 2009;4: 42–50. | ||

Geraghty AW, Wood AM, Hyland ME. Dissociating the facets of hope: agency and pathways predict dropout unguided self-help therapy in opposite directions. J Res Pers. 2010;44:155–158. | ||

Snyder CR, Ilardi SS, Cheavens J, Michael ST, Yamhure L, Sympson S. The role of hope in cognitive-behavioral therapies. Cognit Ther Res. 2000;24:747–762. | ||

Perry BM, Taylor D, Shaw SK. “You’ve got to have a positive state of mind”: an interpretative phenomenological analysis of hope and first episode psychosis. J Ment Health. 2007;16:781–793. | ||

Cheavens JS, Feldman DB, Gum A, Michael ST, Snyder CR. Hope therapy in a community sample: a pilot investigation. Soc Indic Res. 2006;77:61–78. | ||

Benzein E, Norberg A, Saveman BI. The meaning of the lived experience of hope in patients with cancer palliative home care. Palliat Med. 2001;15:117–126. | ||

Lin HR, Bauer-Wu SM. Psycho-spiritual well-being in patients with advanced cancer: an integrative review of literature. J Adv Nurs. 2003;44:69–80. | ||

Shekarabi-Ahari G, Younesi J, Borjali A, Ansari-Damavandi S. The effectiveness of group hope therapy on hope and depression of mothers with children suffering from cancer in Tehran. Iran J Cancer Prev. 2012;5:183–188. | ||

Neenan M, Dryden W. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. London: Sage; 2002. | ||

Kwon P. Hope and dysphoria: the moderating role of defense mechanisms. J Pers. 2000;68:199–223. | ||

Yanos PT, Roe D, Markus K, Lysaker PH. Pathways between internalized stigma and outcomes related to recovery in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:1437–1442. | ||

Ociskova M, Prasko J, Kamaradova D. Relationship between personality and self-stigma in the mixed neurotic spectrum and depressive disorders: a cross-sectional study. Act Nerv Super Rediviva. 2015;57:22–29. | ||

Fung KM, Tsang HW, Chan F. Self-stigma, stages of change and psychosocial treatment adherence among Chinese people with schizophrenia: a path analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2010;45:561–568. | ||

Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. New York: Simon & Schuster; 1963. | ||

Padurariu M, Ciobica A, Persson C, Stefanescu C. Self-stigma in psychiatry: ethical and bio-psycho-social perspectives. Rev Rom Bioet. 2011;9:76–82. | ||

Corrigan PW, Rafacz J, Rüsch N. Examining a progressive model of self-stigma and its impact on people with serious mental illness. Psychiatry Res. 2011;189:339–343. | ||

Livingston JD, Boyd JE. Correlates and consequences of internalized stigma for people living with mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71:2150–2161. | ||

Alonso J, Buron A, Bruffaerts R, et al. Association of perceived stigma and mood and anxiety disorders: results from the World Mental Health Surveys. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;118:305–314. | ||

Ritsher JB, Phelan JC. Internalized stigma predicts erosion of morale among psychiatric outpatients. Psychiatry Res. 2004;129:257–265. | ||

Mosanya TJ, Adelufosi AO, Adebowale OT, Oqunwale A, Adebayo OK. Self-stigma, quality of life and schizophrenia: an outpatient clinic survey in Nigeria. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2014;60:377–386. | ||

Cinculova A, Kamaradova D, Ociskova M, et al. [Self-stigma, treatment adherence, and medication discontinuation in anxiety disorders: a cross-sectional study]. Ceska Slov Psychiatr. 2015;111:577–583. Czech. | ||

Vrbová K, Kamarádová D, Látalová K, et al. Self-stigma and adherence to medication in patients with psychotic disorders: cross-sectional study. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2014;35:645–652. | ||

Hajda M, Kamaradova D, Latalova K, et al. Self-stigma, treatment adherence, and medication discontinuation in patients with bipolar disorders in remission: a cross-sectional study. Act Nerv Super Rediviva. 2015;57:6–11. | ||

Latalova K, Prasko J, Kamaradova D, et al. Self-stigma and suicidality in patients with neurotic spectrum disorder: a cross sectional study. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2014;35:474–480. | ||

Brohan E, Elgie R, Sartorius N, Thornicroft G. Self-stigma, empowerment and perceived discrimination among people with schizophrenia in 14 European countries: the GAMIAN-Europe study. Schizophr Res. 2010;122:232–238. | ||

Bathje GJ, Pryor JB. The relationships of public and self-stigma to seeking mental health services. J Ment Health Couns. 2011;33: 161–176. | ||

Simonds LM, Thorpe SJ. Attitudes towards obsessive compulsive disorders: an experimental investigation. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2003;38:331–336. | ||

Brohan E, Gauci D, Sartorius N, Thornicroft G. Self-stigma, empowerment and perceived discrimination among people with bipolar disorder or depression in 13 European countries: the GAMIAN-Europe study. J Affect Disord. 2010;129:56–63. | ||

Link BG, Struening EL, Rahav M, Phelan JC, Nuttbrock L. On stigma and its consequences: evidence from a longitudinal study of men with dual diagnoses of mental illness and substance abuse. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;38:177–190. | ||

Kamaradova D, Latalova K, Prasko J, et al. [Self-stigma, adherence, and withdrawal of the medication in psychiatric disorders: a cross-sectional study]. Psychiatrie (Stuttg). 2015;19:175–183. Czech. | ||

Yen CF, Chen CC, Lee Y, Tang TC, Yen JY, Ko CH. Self-stigma and its correlates among outpatients with depressive disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:599–601. | ||

Camp DL, Finlay WM, Lyons E. Is low self-esteem inevitable consequence of stigma? An example from women with chronic mental health problems. Soc Sci Med. 2002;55:823–834. | ||

Corchs F, Corregiari F, Ferrão YA, et al. Personality traits and treatment outcome in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2008;30:246–250. | ||

Anderson CB, Joyce PR, Carter FA, McIntosh VV, Bulik CM. The effect of cognitive-behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa on temperament and character as measured by the Temperament and Character Inventory. Compr Psychiatry. 2002;43:182–188. | ||

Quilty LC, Godfrey KM, Kennedy SH, Begby RM. Harm avoidance as a mediator of treatment response to antidepressant treatment of patients with major depression. Psychother Psychosom. 2010;79:116–122. | ||

Kampman O, Viikki M, Järventausta K, Leinonen. Meta-analysis of anxiety disorders and temperament. Neuropsychobiology. 2014;69: 175–186. | ||

Wachleski C, Salum GA, Blaya C, et al. Harm avoidance and self-directedness as essential features of panic disorder patients. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49:476–481. | ||

Margetić BA, Jakovljević M, Ivanec D, Margetić B, Tošić G. Relations of internalized stigma with temperament and character in patients with schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry. 2010;51:603–606. | ||

Cloninger CR. A unified biosocial theory of personality and its role in the development of anxiety states. Psychiatr Dev. 1986;3:167–226. | ||

Kose S. A psychobiological model of temperament and character: TCI. Yeni Symp. 2003;41:86–97. | ||

Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;(59 Suppl 20):22–33; quiz 34–57. | ||

Amorim P. Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): validação de entrevista breve para diagnóstico de transtornos mentains. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2000;22:106–115. | ||

Ritsher JB, Otilingam PG, Grajales M. Internalized stigma of mental illness: psychometric properties of a new measure. Psychiatry Res. 2003;121:31–49. | ||

Ocisková M, Praško J, Kamarádová D, et al. Self-stigma in psychiatric patients: standardization of the ISMI scale. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2014;35:624–632. | ||

Ociskova M, Sobotkova I, Prasko J, Mihal V. Standardizace české verze Škály dispoziční naděje pro dospělé [Standardization of the Adult Dispositional Hope Scale – the Czech version]. Psychologie a její kontexty. In press 2016. | ||

Cloninger CR. The Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI): A Guide to Its Development and Use. St Louis: Centre for Psychobiology of Personality; 1994. | ||

Farmer RF, Goldberg LR. A psychometric evaluation of the revised Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI-R) and the TCI-140. Psychol Assess. 2008;20:281–291. | ||

Preiss M, Kucharová J, Novák T, Stepánková H. The Temperament and Character Inventory – revised (TCI-R): a psychometric characteristics of the Czech version. Psychiatr Danub. 2007;19:27–34. | ||

Brändström S, Richter J, Nylander PO. Further development of the Temperament and Character Inventory. Psychol Rep. 2003;93:995–1002. | ||

Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Rockville (MD): US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; 1976. | ||

Kadouri A, Corruble E, Falissard B. The improved Clinical Global Impression scale (ICGI): development and validation in depression. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7:7. | ||

Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:893–897. | ||

De Ayala RJ, Vonderharr-Carlson DJ, Kim D. Assessing the reliability of the Beck Anxiety Inventory scores. Educ Psychol Meas. 2005;65:742–756. | ||

Kamaradova D, Prasko J, Latalova K, et al. Psychometric properties of the Czech version of the Beck Anxiety Scale: comparison between diagnostic groups. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2016;36:706–712. | ||

Storch EA, Roberti JW, Roth DA. Factor structure, concurrent validity, and internal consistency of the Beck Depression Inventory – second edition in a sample of college students. Depress Anxiety. 2004;19:187–189. | ||

Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 1988;8:77–100. | ||

Preiss M, Vacir K. Beckova Sebeposuzovaci Skala Depresivity pro Dospele: BDI-II. Brno: Psychodiagnostika; 1999. | ||

Bernstein EM, Putnam FW. Development, reliability, and validity of a dissociation scale. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1986;174:727–735. | ||

Waller NG, Ross CA. The prevalence and biometric structure of pathologic dissociation in the general population: taxometric and behavior genetic findings. J Abnorm Psychol. 1996;106:499–510. | ||

Ptacek R, Bob P, Paclt I. [Dissociative Experiences Scale: the Czech version]. Cesk Psychol. 2006;50:262–272. Czech. | ||

Seifertova D, Prasko J, Hoschl C, Horacek J. Postupy v Lecbe Psychickych Poruch. Prague: Academia Medica Pragensis; 2008. | ||

Raboch J, Uhlikova P, Hellerova P, Anders M, Susta P. Psychiatrie: Doporucene Postupy Psychiatricke Pece IV. Prague: Psychiatricka Spolecnost; 2013. | ||

European Medicines Agency. Guideline for good clinical practice. 2002. Available from: http://www.edctp.org/fileadmin/documents/EMEA_ICH-GCP_Guidelines_July_2002.pdf. Accessed May 19, 2016. | ||

Prasko J, Dockery C, Horace J, et al. Moclobemide and cognitive behavioral therapy in the treatment of social phobia: a six-month controlled study and 24 months follow-up. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2006;27:473–481. | ||

Başoğlu M, Marks IM, Kiliç C, et al. Relationship of panic, anticipatory anxiety, agoraphobia and global improvement in panic disorder with agoraphobia treated with alprazolam and exposure. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;164:647–652. | ||

Van Ameringen M, Mancini C, Pipe B, Bennett M. Optimizing treatment of social phobia: a review of treatment resistance. CNS Spectr. 2004;9:753–762. | ||

Kamaradova D, Prasko J, Sandoval A, Latalova K. Therapeutic response to complex cognitive-behavioral and pharmacological treatment in patients with social phobia. Act Nerv Super Rediviva. 2014;56:91–99. | ||

Steketee G, Siev J, Fama JM, Keshaviah A, Chosak A, Wilhelm S. Predictors of treatment outcome in modular cognitive therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28:333–341. | ||

Overbeek T, Schruers K, Vermetten E, Griez E. Comorbidity of obsessive-compulsive disorder and depression: prevalence, symptom severity, and treatment effect. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:1106–1112. | ||

Telch MJ, Kamphuis JH, Schmidt NB. The effects of comorbid personality disorders on cognitive behavioral treatment for panic disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45:469–474. | ||

Thiel N, Hertenstein E, Nissen C, Herbst N, Külz AK, Voderholzer U. The effect of personality disorders on treatment outcomes in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorders. J Pers Disord. 2013;27:697–715. | ||

Prasko J, Houbová P, Novák T, et al. Influence of personality disorder on the treatment of panic disorder: comparison study. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2005;26:667–674. | ||

Vyskocilova J, Prasko J, Novak T, Pohlova L. Is there any influence of personality disorder on the short term intensive group cognitive behavioral therapy of social phobia? Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2011;155:85–94. | ||

Rufer M, Held D, Cremer J, et al. Dissociation as a predictor of cognitive behavior therapy outcome in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychother Psychosom. 2006;75:40–46. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.