Back to Journals » International Journal of General Medicine » Volume 15

Provider Evaluation of a Novel Virtual Hybrid Hospital at Home Model

Authors Maniaci MJ , Maita K , Torres-Guzman RA, Avila FR , Garcia JP, Eldaly A, Forte AJ, Matcha GV, Pagan RJ, Paulson MR

Received 15 December 2021

Accepted for publication 11 February 2022

Published 22 February 2022 Volume 2022:15 Pages 1909—1918

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S354101

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Michael J Maniaci,1 Karla Maita,2 Ricardo A Torres-Guzman,2 Francisco R Avila,2 John P Garcia,2 Abdullah Eldaly,2 Antonio J Forte,2 Gautam V Matcha,1 Ricardo J Pagan,1 Margaret R Paulson3

1Division of Hospital Internal Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL, USA; 2Division of Plastic Surgery, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL, USA; 3Division of Hospital Internal Medicine, Mayo Clinic Health Systems, Eau Claire, WI, USA

Correspondence: Michael J Maniaci, Division of Hospital Internal Medicine, Mayo Clinic, 4500 San Pablo Road, Jacksonville, FL, 32224, USA, Tel +1 904-956-0081, Fax +1904-953-2848, Email [email protected]

Background: Healthcare provider’s experience with new models of care is crucial for long-term success. In July 2020, Mayo Clinic implemented a novel virtual hybrid hospital at home program called Advanced Care at Home (ACH). This model allows virtual providers in a command center to care for high-acuity patients in the home setting through collaboration with a vendor-mediated supply chain. This study aims to describe the outcomes obtained from a survey applied to the ACH providers to determine their acceptance of the quality and safety of the virtual hybrid care model, their perception towards the decision-making and teamwork between the command center and supplier network, and determine if the overall experience with ACH was rewarding.

Methods: A 15-question anonymous survey was distributed via email quarterly to all the physicians and nurse practitioners registered in ACH program at Mayo Clinic. The survey encompassed questions related to the overall experience in ACH concerning work environment, quality of care, service reliability, teamwork, decision-making, and satisfaction. All the questions were Likert-like scale choice, and a descriptive analysis using frequency distribution and percentages of the data was performed.

Results: Between September 1, 2020 and April 30, 2021, three quarterly surveys were sent to a total of 21 physicians and nurse practitioners caring for patients virtually in ACH. The response rate reported was 72%, 33%, and 66%, respectively, at the first, second, and third quarters. Eighty percent or more of providers consistently gave positive scores to all three areas analyzed throughout the 8-month study.

Conclusion: Providers found the ACH virtual hybrid model of home hospital care very rewarding. They were able to deliver high-quality and safe care to their patients through positive teamwork with a vendor-mediated supply chain. This novel model of hospital at home has the potential to be a great provider satisfier moving forward.

Keywords: telemedicine, virtual hybrid, hospital home, home healthcare, provider satisfaction

Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the healthcare delivery system experienced exponential changes, where telemedicine played the leading role.1–3 Telemedicine can provide high-quality care4,5 and is particularly useful during the current pandemic to guarantee excellent patient attention while avoiding overcrowded emergency departments and maintaining physical distancing.6,7 Leveraging this surge in telemedicine, Mayo Clinic instituted a new model of hospital at home called Advanced Care at Home (ACH). ACH is a virtual hybrid home hospital program where care is managed virtually by remote providers in a command center and executed through external vendors in an integrated health care supply chain. As only using in-person physicians and bedside nurses had limited overall scalability in previous models of hospital at home, ACH hoped to mimic the success of patient volume scalability seen in recent virtual remote patient monitoring programs.8 In ACH, patients receive hospital-level care in the comfort of their own home. Hospital physicians and bedside nurses interact with the patients via a video interface that connects the patients at home with a hospital command center. Biometric monitoring is done via Bluetooth connected devices (blood pressure cuff, pulse oximeter, scale, etc) and patients are monitored from their homes using a technology stack which enables the data to be fed back to their clinical team in the command center. The virtual-only physicians and bedside nurses in the command center make all the medical decisions in regards to the patient care plan and then execute that plan by activating in-person visits by contracted medical vendors to provide in-home services such as medication administration, infusions, and labs.

In the healthcare setting, one essential measurement for quality of service is the satisfaction of providers.9 For providers, high levels of fulfillment and low levels of burnout lead them to enjoy their practice, improving the provider–patient interaction and increasing positive health outcomes in the clinical practice.10 In previous models of hospital at home where all care given was in-person, evaluations providers were accepting of the model of care, satisfied with the type of care given to patients, and overall were happy with the experience.11,12 But in ACH, the physician and bedside registered nurse care is all virtual in nature, coming from a command center. This leads to the question of whether the provider experience would be positive in this new hospital at home model. Previous studies on telemedicine have shown that although providers are often accepting of the model, there are often concerns over the quality of care delivered and the long-term satisfaction with virtual care.13,14 We hypothesize that healthcare providers will be accepting of the quality and safety of the virtual hybrid care model, have a positive attitude towards the decision-making and teamwork between the command center and supplier network, and find working in the ACH program rewarding. This study aims to describe the outcomes obtained from a survey applied to the ACH providers to determine their experience working with this novel virtual hybrid hospital at home program.

Methods

Population and Setting

This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board as a retrospective review under protocol number 20-010753. The study was conducted between September 1, 2020 and April 30, 2021 at Mayo Clinic in Florida, a 306-bed community academic hospital. All physicians and advanced practice providers caring for patients in ACH were included in the study.

ACH Model of Care

Patients are admitted to the ACH program either directly from the emergency department or from the hospital wards. Patients are screened for both clinical stability (deterioration index, unplanned readmission score, and hierarchical condition category (HCC) score) as well as demographic eligibility (language, ZIP code, and type of insurance) prior to admission to the program. A social stability screen is also done to insure that the home setting is safe for both the patients and the in-home care providers. The primary responsibilities delegated to the family member(s) are to guarantee a safe environment for the patient, meaning the decreased risk for falls, assistance with routine tasks or equipment, and help the patient with the treatment plan agreed between them and the team.

Patients are monitored from the comfort of their homes using a technology stack and a specially configured audio/video communication device to directly communicate with their clinical team in the command center. The command center activates a vendor-mediated supply chain to provide in-home rapid response services, phlebotomy, medication administration, nursing care, meals, and diagnostic images such as abdominal and chest radiographs. When the patients have reached a stable endpoint, and no hospital setting services are required, the patients were then discharged to the respective primary care provider.

Data Collection

A 15-question anonymous survey was distributed via email to all the physicians and nurse practitioners enrolled in ACH every 3 to 4 months since the service’s implementation. All the incomplete surveys were excluded. The participation was voluntary, and any responder could withdraw from the survey at any moment. Five questions were directed to the acceptance of the quality and safety of the program, three questions looked at decision-making and teamwork, and seven questions looked at aspects of rewarding work, joy, and burnout.

All the questions were Likert-like scale choices using the following answers: (1) strongly agree or extremely satisfied; (2) somewhat agree or satisfied; (3) neither agree nor disagree or satisfied nor dissatisfied; (4) somewhat disagree or dissatisfied; (5) strongly disagree or dissatisfied. Only one question used a different scale. This question referred to time in which the providers experienced joyful feelings. The answers for this question were the following: (1) Always; (2) Most of the time (3) About half the time (4) Sometimes (5) Never. The survey questions are itemized in Figure 1.

|

Figure 1 ACH provider’s survey. |

Study data were collected and managed using electronic data capture tools hosted at Mayo Clinic. Data analysis used standard descriptive statistics for all of the data collected using frequency distribution and percentages. The three sets of provider surveys were evaluated using the Kruskal–Wallis test and a p-value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

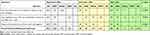

Between September 1, 2020 and April 30, 2021, 224 patients were care for by the virtual providers in the ACH program. A total of 11 providers received the first survey, 15 providers received the second survey, and 21 providers received the third survey. The sum of the surveys completed in the three analyzed quarters resulted in 33 surveys. Six surveys were excluded because the answers were incomplete, and therefore only 27 surveys were analyzed. The quarterly response rate was between 33% and 72%. Each section of questions (quality and safety, decision-making and teamwork, and finding work rewarding) had the answers summarized into an overall Likert scale for each time interval (Tables 1–3). Due the negative responses indicating a positive perspective on the burnout question, it was not included in the summarized scale and is reported separately in Table 3.

|

Table 1 Providers’ Perception of ACH Quality and Safety |

|

Table 2 Providers’ Perception of Decision Making and Teamwork in ACH |

|

Table 3 Providers’ Perception of ACH Being Rewarding |

First Survey – September 2020

Eight out of 11 providers (72%) completed the survey completely. Regarding the overall scoring on the quality and safety questions, providers responded positively, denoted by answering “strongly agree or somewhat agree” or “extremely satisfied or somewhat satisfied”, 100% of the time. Providers responded positively to questions on decision-making and teamwork 91.6%, responded neutrally 4.2% of the time, and responded negatively 4.2% of the time. Providers responded positively to questions about ACH being rewarding 89.6% of the time, responded neutrally 2.1% of the time, and responded negatively 8.4% of the time. Only 12.5% of providers reported feeling burnt out from their work, with 62.5% of providers not reporting burnout and 25% remaining neutral.

Second Survey – December 2020

Five out of 15 providers (33%) completed the survey. Regarding the overall scoring on the quality and safety questions, providers responded positively, denoted by answering “strongly agree or somewhat agree” or “extremely satisfied or somewhat satisfied”, 84% of the time and remained neutral 16% of the time. Providers responded positively to questions on decision-making and teamwork 80% of the time, responded neutrally 13.3% of the time, and responded negatively 6.7% of the time. Providers responded positively to questions about ACH being rewarding 90% of the time, responded neutrally 6.7% of the time, and responded negatively 3.3% of the time. The question on burnout had an even number of responses among all five Likert choices (20%).

Lower scores were seen in five questions compared to the previous survey with a drop from 100% to 80% in the positive responses to the question on the ability for people to work well together, and the quality of the technology, a drop in satisfaction in decision-making (87.5% to 60%) and a drop in the feeling of joy (100% to 60%). None of these changes met statistical significance over the three survey periods. The largest drop seen was in the ability to provide service and supplies to home hospital patients (100% to 40%) and this trend did reach statistical significance (p=0.0425) by the Kruskal–Wallis test when compared over the three survey periods.

Third Survey – April 2021

Twenty providers answered the survey, but six surveys were eliminated due to be incomplete. Therefore, only 14 out of 21 surveys (66%) were analyzed. Regarding the overall scoring on the quality and safety questions, providers responded positively, denoted by answering “strongly agree or somewhat agree” or “extremely satisfied or somewhat satisfied”, 91.6% of the time, remained neutral 4.2% of the time, and gave a negative response 4.2% of the time. Providers responded positively to questions on decision-making and teamwork 86% of the time, responded neutrally 7% of the time, and responded negatively 7% of the time. Providers responded positively to questions about ACH being rewarding 83.3% of the time, responded neutrally 11.8% of the time, and responded negatively 4.7% of the time. Only 42% of providers reported not feeling burnt out from their work, with 29% of providers reporting some burnout and 29% remaining neutral.

Higher scores were seen in the five questions related to the technology provided (85% vs 80%), the service and supplies needed for care (86% vs 40%), satisfaction in involvement in work decisions (75% vs 60%), and the feeling of joy in the last week (71% vs 60%). Lower scores were seen in three questions compared to the previous survey with a drop from 100% to 93% in the positive responses to the questions on the sense of ownership and responsibility at work and the work environment being conducive to learning from mistakes. The largest drop was seen in the positive response to the question on the work providing a sense of achievement (100% to 57%). None of these changes met statistical significance.

Discussion

This study focused on assessing providers' experiences with a new model of hospital at home. We focused on three key areas when assessing this virtual hybrid model of care: providers perception of quality and safety, providers perception of decision-making and teamwork, and whether providers found working in ACH rewarding. Overall, our data show that the providers adapted well to this new model of care, with 80% or more of providers giving positive scores to all three areas analyzed consistently throughout the 8-month study. These positive findings are consistent with the experiences reported by providers on the previous models of hospital at home.11,12

These findings are very important as there was a strong concern that both the virtual nature of the providers’ interactions with the patients as well as the necessity to work with outside vendors to provide in-home care delivery would result in a poor experience for our providers. Although there were a few individual questions where the percent of positive answers fluctuated month to month, overall, the vast majority of providers reported a consistent positive experience. The healthcare stakeholder’s perception is crucial to evaluate the effectiveness of the new system being implemented. Both patients and providers are facing rapid expansion of new care delivery models, and some argue that telemedicine is a tool that causes erosion in the empathic physician–patient relationship, leading to care depersonalization. However, there are countless documented benefits, especially in patients with chronic conditions that require several encounters, in decreasing the cost of care, avoid missing appointments, and increasing the adherence to the treatment.15 Even though the vast majority of the studies evaluating the efficacy of telemedicine in providing quality of care are focused on the patients’ point of view,16–18 it has also been observed that the role of the providers to accomplish patient satisfaction is of utter importance.19–21 Based on that, a high level of work satisfaction will bring a high level of patient satisfaction, meeting the established standards to provide quality medical care.

One of the several factors that determine a provider’s satisfaction is meeting the patient’s needs by delivering high-quality care.22 More than 80% of the participants agreed that ACH could provide a high quality of care to the patients, which speaks to the providers largest concern with new models of telemedicine.13,14 This makes sense as one key aspect that often contributes to an enjoyable work environment is the reliability of the system one is working in. One consistent finding was the extremely high scores on the questions related to system reliability in every quarter the survey was conducted in. Across all three quarters, 100% of the providers answered “strongly agree or somewhat agree” to the questions on feeling safe being treated in ACH and willingness to recommend ACH to a loved one and the question on ability to provide high-quality care averaged 95%. We believe that this safe and reliable backbone helped to enable providers to achieve such high patient satisfaction scores. Moreover, safety is often related to the ability in interact with patients quickly through the ACH technology. Between 80 to 100% of the providers somewhat agreed and strongly agreed that they could safely deliver care to the patients using the technology offered by ACH. In 2020, Kissi et al23 showed that the ease of use and usefulness of the service employed influenced the provider’s satisfaction regarding the use of technology. Continuing to emphasize the high quality and safety aspects of this virtual hybrid model should help contribute to ongoing positive provider experience scores.

One interesting finding was the fluctuating responses to the question on burnout. Providers reported burnout 12.5% of the time during the first survey, but this increased to 40% on the second survey before dropping a bit to 29% on the third survey. These fluctuating results were not found to be statistically significant, which could be due to the low number of surveys returned during the second timeframe. Even so, this burnout rate is still a degree lower than most burnout data. In the United States, in 2017, the Medscape Lifestyle Report showed a nationwide burnout rate of 51% among physicians.24 In 2018, the rate of burnout between nurses was 31.5%.20 Since these figures seem to be increasing, we have to develop further research about this topic to go deeper into the providers’ perceptions to avoid a detrimental quality of patient care. Malouff et al1 recently published some results about the use of telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic and the physician’s perception of burnout, reporting that one-third of the physicians at Mayo Clinic Florida working with telemedicine experienced an improvement either in work–life balance or burnout symptoms. A reduction in driving time to the workplace gaining more time to spend with family and hobbies are some of the benefits of telemedicine with regard decrease the risk of burnout,25 being these some positive factors that the ACH program has in its favor. Further studies on the virtual hybrid model and its association with provider burnout are warranted.

Limitations

One of the most striking limitations is the sample size leading to a lack of study power. Although statistical analysis was done, only 1 out of the 15 question’s results reached significance; a larger sample size may have led to more significant findings. Additionally, the subjectivity in interpreting the results is a source of bias in descriptive survey-based studies, as well as the rate of responses and the completion of the survey playing a determining key in the study drawbacks.

Conclusion

Providers found the ACH virtual hybrid model of home hospital care very rewarding. They were able to deliver high-quality and safe care to their patients through positive teamwork with a vendor-mediated supply chain. Focusing on safety, quality, and teamwork are ways we can bring joy to providers and reduce burnout in the new model of care.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Malouff TD, TerKonda SP, Knight D, et al. Physician satisfaction with telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic: the Mayo Clinic Florida experience. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2021;5:771–782.

2. Miner H, Fatehi A, Ring D, Reichenberg JS. Clinician telemedicine perceptions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Telemed J E Health. 2021;27(5):508–512.

3. Webster P. Virtual health care in the era of COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395(10231):1180–1181.

4. Lukas H, Xu C, Yu Y, Gao W. Emerging telemedicine tools for remote COVID-19 diagnosis, monitoring, and management. ACS Nano. 2020;14(12):16180–16193.

5. Portnoy JM, Waller M, De Lurgio S, Dinakar C. Telemedicine is as effective as in-person visits for patients with asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;117(3):241–245.

6. Burroughs M, Urits I, Viswanath O, Simopoulos T, Hasoon J. Benefits and shortcomings of utilizing telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic. In: Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings. Vol. 33. Taylor & Francis; 2020:699–700.

7. Chauhan V, Galwankar S, Arquilla B, et al. Novel coronavirus (COVID-19): leveraging telemedicine to optimize care while minimizing exposures and viral transmission. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2020;13(1):20–24.

8. Sitammagari K, Murphy S, Kowalkowski M, et al. Insights from rapid deployment of a “virtual hospital” as standard care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(2):192–199.

9. Nguyen M, Waller M, Pandya A, Portnoy J. A review of patient and provider satisfaction with telemedicine. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2020;20(11):72.

10. Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):573–576.

11. Marsteller JA, Burton L, Mader SL, et al. Health care provider evaluation of a substitutive model of hospital at home. Med Care. 2009;47(9):979–985.

12. Utens CM, Goossens LM, van Schayck OC, et al. Evaluation of health care providers’ role transition and satisfaction in hospital-at-home for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations: a survey study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;27(13):363.

13. Alkureishi MA, Choo ZY, Lenti G, et al. Clinician perspectives on telemedicine: observational cross-sectional study. JMIR Hum Factors. 2021;8(3):e29690.

14. Schinasi DA, Foster CC, Bohling MK, Barrera L, Macy ML. Attitudes and perceptions of telemedicine in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey of Naïve Healthcare Providers. Front Pediatr. 2021;7(9):647937.

15. Temesgen ZM, DeSimone DC, Mahmood M, Libertin CR, Varatharaj Palraj BR, Berbari EF. Health care after the COVID-19 pandemic and the influence of telemedicine. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(9s):S66–S68.

16. Junewicz A, Youngner SJ. Patient-satisfaction surveys on a scale of 0 to 10: improving health care, or leading it astray? Hastings Cent Rep. 2015;45(3):43–51.

17. Polinski JM, Barker T, Gagliano N, Sussman A, Brennan TA, Shrank WH. Patients’ satisfaction with and preference for telehealth visits. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(3):269–275.

18. Kruse CS, Krowski N, Rodriguez B, Tran L, Vela J, Brooks M. Telehealth and patient satisfaction: a systematic review and narrative analysis. BMJ Open. 2017;7(8):e016242.

19. McHugh MD, Kutney-Lee A, Cimiotti JP, Sloane DM, Aiken LH. Nurses’ widespread job dissatisfaction, burnout, and frustration with health benefits signal problems for patient care. Health Aff. 2011;30(2):202–210.

20. Haas JS, Cook EF, Puopolo AL, Burstin HR, Cleary PD, Brennan TA. Is the professional satisfaction of general internists associated with patient satisfaction? J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(2):122–128.

21. DiMatteo MR, Sherbourne CD, Hays RD, et al. Physicians’ characteristics influence patients’ adherence to medical treatment: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Health Psychol. 1993;12(2):93–102.

22. Friedberg MW, Chen PG, Van Busum KR, et al. Factors affecting physician professional satisfaction and their implications for patient care, health systems, and health policy. Rand Health Q. 2014;3(4):1.

23. Kissi J, Dai B, Dogbe CS, Banahene J, Ernest O. Predictive factors of physicians’ satisfaction with telemedicine services acceptance. Health Informatics J. 2020;26(3):1866–1880.

24. Reith TP. Burnout in United States healthcare professionals: a narrative review. Cureus. 2018;10:e3681.

25. Vogt EL, Mahmoud H, Elhaj O. Telepsychiatry: implications for psychiatrist burnout and well-being. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70(5):422–424.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.