Back to Journals » Cancer Management and Research » Volume 10

Prognostic significance of pretreatment lymphocyte/monocyte ratio in retroperitoneal liposarcoma patients after radical resection

Authors Luo P , Cai W, Yang L , Chen S, Wu Z, Chen Y, Zhang R, Shi Y, Yan W, Wang C

Received 19 April 2018

Accepted for publication 9 August 2018

Published 18 October 2018 Volume 2018:10 Pages 4727—4734

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CMAR.S171602

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Lu-Zhe Sun

Peng Luo,1,2 Weiluo Cai,1,2 Lingge Yang,1,2 Shiqi Chen,1,2 Zhiqiang Wu,1,2 Yong Chen,1,2 Ruming Zhang,1,2 Yingqiang Shi,1,2 Wangjun Yan,1,2 Chunmeng Wang1,2

1Department of Bone and Soft Tissue Sarcomas, Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center, Shanghai, People’s Republic of China; 2Department of Oncology, Shanghai Medical College, Fudan University, Shanghai, People’s Republic of China

Background: The aim of this study was to evaluate the prognostic value of pretreatment inflammatory biomarkers in retroperitoneal liposarcoma (RPLS) patients after radical resection.

Patients and methods: One hundred patients with RPLS who underwent radical resection between September 2004 and October 2010 at Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center were included in this study. Laboratory tests of peripheral blood were sampled before surgery. The optimal cutoff values of systemic inflammatory markers were defined by receiver-operating curve analyses. Curves of disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) were obtained by the Kaplan–Meier method. Cox proportional hazards regression modeling was used to perform univariate and multivariate analyses.

Results: The median follow-up time was 53 months. The median DFS and OS were 27 and 86 months, respectively. On the basis of the optimal cutoff value of 3, 24 patients were classified into low lymphocyte/monocyte ratio (LMR) group and 76 patients into high LMR group. In univariate analysis, low LMR group had significantly shorter DFS (P<0.001) and OS (P<0.001) compared to high LMR group. In multivariate analysis, low LMR was demonstrated as an independent negative prognostic factor for both DFS (HR=2.854, 95% CI=1.392–5.851, P=0.004) and OS (HR=3.897, 95% CI=1.681–9.033, P=0.002).

Conclusion: Pretreatment LMR is a useful prognostic marker in RPLS patients after radical resection.

Keywords: retroperitoneal liposarcoma, inflammatory biomarkers, prognosis, lymphocyte, monocyte ratio

Background

Liposarcoma (LS), a rare disease derived from adipocyte progenitor, is the second most common soft tissue sarcoma (STS) affecting adulthood, accounting for approximately 20% of new diagnoses. Extremities (24%) and retroperitoneum (45%) are two predilection sites for LS.1

With surgical resection maintaining the cornerstone of curative treatment, the 5-year disease-free survival (DFS) and 5-year overall survival (OS) of retroperitoneal liposarcoma (RPLS) were 41%–50% and 54%–70%, respectively.2,3 A number of existing literatures reported the prognostic factors of RPLS.3–5 However, the inaccuracy and inadequacy of those established parameters for predicting prognosis including multifocality, tumor integrity, histological subtype, margin status, and the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) TNM stage have gradually been demonstrated in clinical practice. Therefore, a more reliable and more convenient predictor for RPLS patients after radical resection is in urgent need.

Recent studies proved the important role of inflammatory response in tumorigenesis and tumor progression.6–8 Besides, an increasing number of researches revealed that systemic inflammatory markers such as neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet/lymphocyte ratio (PLR), lymphocyte/monocyte ratio (LMR), platelet/monocyte ratio (PMR), and albumin/globulin ratio (AGR) could be utilized to evaluate the prognosis of various malignancies, including colorectal cancer, adrenocortical carcinoma, pancreatic cancer, ovarian cancer, and STS.9–19 However, there was no literature focusing on the correlation between inflammatory markers and the prognosis of RPLS. As a result, we conducted this study to explore the prognostic value of NLR, PLR, LMR, PMR, and AGR in RPLS patients after radical resection.

Patients and methods

Patient selection

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients. The criteria for inclusion were as follows: 1) 18 years of age or older; 2) histologically confirmed diagnosis of LS by two experienced pathologists; 3) radically resected (R0/R1 resection) localized disease (without distant metastasis) at the time of surgery; 4) no metabolic, infectious, chronic inflammatory, or autoimmune diseases; 5) no treatment of antibiotics, steroid, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy before surgery; and 6) laboratory tests of peripheral blood sample before surgery.19 Ultimately, 100 patients with RPLS who underwent radical resection between September 2004 and October 2017 at Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center were included in this study.

The comprehensive information of age, gender, tumor size, admission status, and treatment records were obtained from medical history. Histological subtype was categorized into well-differentiated LS (WDLS), dedifferentiated LS (DDLS), myxoid LS (MLS), round cell LS (RLS), and pleomorphic LS (PLS) on the basis of the Evans classification.20 WDLS and MLS are low-grade tumors, which featured a low frequency of metastasis, whereas DDLS, RLS, and PLS are high-grade tumors with more aggressive biological behavior leading to worse prognosis.21,22 Multifocal disease was defined as having more than one distinct tumor nodules. Tumor integrity was classified into fragmentary group (piecemeal resection or tumor rupture during resection) and intact group on the basis of operative report and/or pathology report. The results of laboratory tests including pretreatment hematologic cell counts and albumin and globulin level were obtained from medical records.

The NLR was derived by dividing the neutrophil count by the lymphocyte count; the PLR was derived by dividing the platelet count by the lymphocyte count; the LMR was derived by dividing the lymphocyte count by the monocyte count; the PMR was derived by dividing the platelet count by the monocyte count; and the AGR was obtained by dividing the albumin level by the globulin level.

Follow-up data

After radical resection, all patients were arranged for surveillance imaging such as ultrasound, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance every 3–4 months for the first year, then every 6 months for the next 2 years, and then yearly.

OS was counted as the interval from the date of surgery to the date of death (event) related to the disease (or complications). DFS was calculated from the date of surgery to the date of disease relapse (local recurrence or distant metastases) or death without evidence of disease relapse. For patients alive and without records of disease relapse, follow-up was censored at the time of last follow-up. Follow-up data were collected by phone call and/or outpatient records. All 100 patients were continuously followed up to March 2018, the time of final follow-up, or the date of death.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 21.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) was applied for statistical analysis. Differences between groups were compared by the chi-squared test. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses were conducted with OS as endpoint. The optimal cutoff values of LMR, NLR, PMR, PLR, and AGR were determined at the point of the maximal Youden’s index.18,23 The median OS and DFS were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method. Curves of DFS and OS were also obtained by the Kaplan–Meier method. Log-rank test was applied to compare the survival between groups. Cox proportional hazards regression modeling was used to perform univariate and multivariate analyses. The factors that identified statistical significance in the univariate analysis were then put into multivariate analysis. All tests were two sided with a significance level set at P<0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics and optimal cutoff values

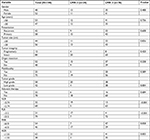

The clinicopathological characteristics of the 100 RPLS patients were listed at length in Table 1. There were 48 males and 52 females. The median age was 50 years (range, 27–78 years). Fifty-eight patients presented with primary tumor, while 42 with recurrent disease. The median tumor size was 18 cm (range, 2–50 cm), <20 cm in 56 patients and ≥20 cm in 44 patients. Eighty-eight patients underwent surgery with intact tumor, while 12 received piecemeal resection. Concomitant organ resection was performed on 52 patients. Twenty-five patients presented with multifocal disease. In case of histological subtypes, 39 patients were of WDLS, 51 DDLS, 3 MLS, 2 RLS, and 5 PLS. As a result, there were 42 patients with low-grade tumors, while 58 with high-grade tumors. Of 100 patients, 10 patients received adjuvant chemotherapy, seven gained adjuvant radiotherapy, and five obtained both therapies. The average cell count (×109/L) of neutrophil, lymphocyte, platelet, and monocyte was 3.93±1.56, 1.58±0.48, 245.50±91.47, and 0.48±0.16, respectively. The average level (g/L) of albumin and globulin were 41.28±5.32 and 29.66±5.43, respectively.

According to the ROC analysis (Figure 1), the area under the curve (AUC) for NLR, PLR, LMR, PMR, and AGR were 0.548 (95% CI, 0.434–0.658, P=0.4615), 0.537 (95% CI, 0.423–0.648, P=0.5772), 0.651 (95% CI, 0.538–0.753, P=0.0164), 0.647 (95% CI, 0.533–0.749, P=0.0189), and 0.686 (95% CI, 0.574–0.784, P=0.0020), respectively. The maximal Youden’s index for NLR, PLR, LMR, PMR, and AGR were 0.132, 0.140, 0.329, 0.299, and 0.377, respectively. The optimal cutoff value for NLR, PLR, LMR, PMR, and AGR were 2.74, 212, 3, 610, and 1.55, respectively. Details of ROC analysis were summarized in Table 2.

Data analysis

At the end of the study follow-up, 67 patients remained alive, and 66 patients suffered disease recurrence. The 5-year DFS and 5-year OS rates were 20.6% and 64.7%, respectively. The median follow-up duration, median DFS, and median OS were 53, 27, and 86 months, respectively.

In univariate analysis, shorter OS was significantly associated with fragmentary resection (median OS, 33 vs 115 months, P=0.004), multifocality (median OS, 48 vs 97 months, P=0.001), high-grade tumor (median OS, 58 vs 158 months, P<0.001), low LMR (median OS, 48 vs 86 months, P<0.001), low PMR (median OS, 72 vs 158 months, P=0.030; Figure 2A), and low AGR (median OS, 66 vs 81 months, P=0.026). Shorter DFS was significantly associated with recurrent disease (median DFS, 21 vs 30 months, P=0.031), fragmentary resection (median DFS, 11 vs 28 months, P=0.011), multifocality (median DFS, 12 vs 31 months, P<0.001), high-grade tumor (median DFS, 21 vs 46 months, P<0.001), high PLR (median DFS, 20 vs 30 months, P=0.050), and low LMR (median DFS, 13 vs 31 months, P<0.001; Figure 2B). Details of univariate analysis were presented in Table 3.

| Figure 2 Kaplan–Meier survival curves for OS (A) and DFS (B) according to pretreatment LMR. Abbreviations: DFS, disease-free survival; LMR, lymphocyte/monocyte ratio; OS, overall survival. |

In multivariate analysis, fragmentary resection (OS: HR, 4.602, 95% CI, 1.851–11.438, P=0.001; DFS: HR, 2.697, 95% CI, 1.350–5.385, P=0.005), multifocality (OS: HR, 4.265, 95% CI, 1.836–9.906, P=0.001; DFS: HR, 3.415, 95% CI, 1.737–6.716, P<0.001), high-grade tumor (OS: HR, 6.515, 95% CI, 1.773–23.946, P=0.005; DFS: HR, 1.915, 95% CI, 1.059–3.463, P=0.031), and low LMR (OS: HR, 3.897, 95% CI, 1.681–9.033, P=0.002; DFS: HR, 2.854, 95% CI, 1.392–5.851, P=0.004) remained statistically significant for both OS and DFS. Details of multivariate analysis were listed in Table 4.

Discussion

Increasing evidences revealed the correlation between inflammatory biomarkers and the prognosis of diversified malignancies, including STS.9–19 However, almost all of the existing literatures about STS were histology non-specific, which mingled various histologic subtypes of STS.9,14–17 As known earlier, STS represented a complex group of neoplasms of mesenchymal origin, and the prognosis might vary markedly based on different histologic subtypes and different tumor locations. Therefore, we argued that it would be more helpful in clinical practice if we could conduct histology- and location-specific researches.

This is the first study, to the best of our knowledge, that focuses specifically on the prognostic values of the inflammatory biomarkers in radically resected RPLS patients. In addition, our findings prove preoperative LMR to be an independent prognostic factor of both OS and DFS for radically resected RPLS patients.

In this study, we retrospectively assessed the prognostic values of NLR, PLR, LMR, PMR, and AGR by using the clinicopathologic data of 100 patients. NLR was the most common reported inflammatory index for STS.9,15,16 However, we did not observe any significant effect of NLR on patients’ outcome in this cohort. There was also a study showing that low PLR was associated with poor survival among STS patients, an effect that was not observed in this study.17 The absence of prognostic value of NLR and PLR in this cohort might be explained by the following two reasons. First, perhaps NLR and PLR possessed no prognostic value for RPLS indeed. As previous researches contained various histologic subtypes of STS, the correlations between RPLS and NLR/PLR were probably obscured by the large number of the entire samples.9,15–17 Second, our samples might be not large enough to discover their prognostic values. In case of PMR, there was no report showing the prognostic significance of PMR in patients with malignancy. In this study, low PMR was adversely associated with OS (P=0.030) in univariate analysis. However, it lost the significance in multivariate analysis (P=0.711). In the previous report that comprised 5,336 patients from our institution, low AGR was proven to be an independent predicator for colorectal cancer patients after curative resection.19 In this study, low AGR group showed worse OS in univariate analysis (P=0.026), but it was not statistically significant in multivariate analysis (P=0.677). In terms of LMR, pretreatment LMR was reported to be independently associated with patients’ outcomes among various malignancies, including colorectal cancer, malignant pleural mesothelioma, hepatocellular carcinoma, gastric cancers, and STS.14,19,24–26 Szkandera et al14 reported that LMR<2.85 was associated with worse prognosis in STS patients. In this research, low LMR was proven to be an independent adverse prognostic factor for both OS (P=0.002) and DFS (P=0.004). Probably owing to the better specificity of samples of this study, the optimal cutoff value of LMR was slightly higher in this study than that in the study by Szkandera et al14 (3 vs 2.85).

Despite we discovered the prognostic significance of low LMR in radically resected RPLS patients, the biological mechanism behind this phenomenon remained unknown. Nevertheless, we could find some clues through previous experimental studies.

Generally, solid tumors are infiltrated with leukocytes, and the interactions between tumor cells and white blood cells have substantial effects on tumor progression.14 As known earlier, lymphocytes represent the host antitumor immunity, playing a pivotal role in cytotoxic cell death and the inhibition of tumor cell proliferation and migration.8,27,28 Lymphocytopenia has been observed in various malignancies, which was assumed to be responsible for the insufficient immunologic response to the tumor, consequently leading to tumor growth, invasion, and metastases.29,30 Furthermore, peripheral monocytes have been reported to be connected with the formation and the presence of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs).31 TAMs are capable of releasing soluble factors that stimulate neo-angiogenesis, cell proliferation, and migration of tumor.8,32 Elevated TAMs, which may be reflected by elevated circulating monocytes, have been revealed to be correlated with poor prognosis.32,33 As mentioned above, decreased lymphocytes count and increased monocytes count reflect deficient antitumor immunity and elevated malignant potentiality, respectively. As a result, we can make sense of the correlation between low LMR and poor prognosis in RPLS patients.

In case of the biology of RPLS concerning inflammation and immune system, there were few literatures mentioning this at present.34–36 Tseng et al34 observed tertiary lymphoid structures (TLSs) formed by tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in fresh surgical specimens of eight RP WDLS and RP DDLS patients. However, TLSs were associated with worse clinical outcome according to the statistical analysis. On the contrary, TLSs were reported to be associated with favorable patients’ outcomes in non-small cell lung cancer and colorectal cancer.35,36 Thus, further studies with large number and more histologic subtypes of cases are needed to clarify the correlation between TILs and the biology of RPLS.

This study demonstrates the significant role of pretreatment LMR in RPLS patients after radical resection. As the immunotherapy advances at a miraculous pace, new drugs that target lymphocytes and monocytes may improve the outcomes of RPLS patients with high pretreatment LMR.

The principal advantages of this study are the specificity of the research sample and the relatively long follow-up period. The main limitation is the small sample size. Further studies with large numbers of patients are required in the future.

Conclusion

This study focuses on the correlation between inflammatory biomarkers and the prognosis in radically resected RPLS for the first time. Low LMR is demonstrated to be an independent predicator for both DFS and OS. We hope our research may facilitate further studies and clinical practice.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Crago AM, Singer S. Clinical and molecular approaches to well differentiated and dedifferentiated liposarcoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 2011;23(4):373–378. | ||

Liles JS, Tzeng CW, Short JJ, Kulesza P, Heslin MJ. Retroperitoneal and intra-abdominal sarcoma. Curr Probl Surg. 2009;46(6):445–503. | ||

Bonvalot S, Rivoire M, Castaing M, et al. Primary retroperitoneal sarcomas: a multivariate analysis of surgical factors associated with local control. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(1):31–37. | ||

Dalal KM, Kattan MW, Antonescu CR, Brennan MF, Singer S. Subtype specific prognostic nomogram for patients with primary liposarcoma of the retroperitoneum, extremity, or trunk. Ann Surg. 2006;244(3):381–391. | ||

Anaya DA, Lahat G, Wang X, et al. Postoperative nomogram for survival of patients with retroperitoneal sarcoma treated with curative intent. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(2):397–402. | ||

Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–674. | ||

Diakos CI, Charles KA, Mcmillan DC, Clarke SJ. Cancer-related inflammation and treatment effectiveness. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(11):e493–e503. | ||

Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454(7203):436–444. | ||

Szkandera J, Absenger G, Liegl-Atzwanger B, et al. Elevated preoperative neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio is associated with poor prognosis in soft-tissue sarcoma patients. Br J Cancer. 2013;108(8):1677–1683. | ||

Absenger G, Szkandera J, Stotz M, et al. Preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts clinical outcome in patients with stage II and III colon cancer. Anticancer Res. 2013;33(10):4591–4594. | ||

Spolverato G, Maqsood H, Kim Y, et al. Neutrophil-lymphocyte and platelet-lymphocyte ratio in patients after resection for hepato-pancreatico-biliary malignancies. J Surg Oncol. 2015;111(7):868–874. | ||

Bagante F, Tran TB, Postlewait LM, et al. Neutrophil-lymphocyte and platelet-lymphocyte ratio as predictors of disease specific survival after resection of adrenocortical carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2015;112(2):164–172. | ||

Cho H, Hur HW, Kim SW, et al. Pre-treatment neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio is elevated in epithelial ovarian cancer and predicts survival after treatment. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2009;58(1):15–23. | ||

Szkandera J, Gerger A, Liegl-Atzwanger B, et al. The lymphocyte/monocyte ratio predicts poor clinical outcome and improves the predictive accuracy in patients with soft tissue sarcomas. Int J Cancer. 2014;135(2):362–370. | ||

Idowu OK, Ding Q, Taktak AF, Chandrasekar CR, Yin Q. Clinical implication of pretreatment neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in soft tissue sarcoma. Biomarkers. 2012;17(6):539–544. | ||

Szkandera J, Gerger A, Liegl-Atzwanger B, et al. The derived neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio predicts poor clinical outcome in soft tissue sarcoma patients. Am J Surg. 2015;210(1):111–116. | ||

Que Y, Qiu H, Li Y, et al. Preoperative platelet-lymphocyte ratio is superior to neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic factor for soft-tissue sarcoma. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:648. | ||

Li YJ, Yang X, Zhang WB, et al. Clinical implications of six inflammatory biomarkers as prognostic indicators in Ewing sarcoma. Cancer Manag Res. 2017;9:443–451. | ||

Li Y, Jia H, Yu W, et al. Nomograms for predicting prognostic value of inflammatory biomarkers in colorectal cancer patients after radical resection. Int J Cancer. 2016;139(1):220–231. | ||

Evans HL. Liposarcoma: a study of 55 cases with a reassessment of its classification. Am J Surg Pathol. 1979;3(6):507–524. | ||

Oh YJ, Yi SY, Kim KH, Yj O, Sy Y, et al. Prognostic Model to Predict Survival Outcome for Curatively Resected Liposarcoma: A Multi-Institutional Experience. J Cancer. 2016;7(9):1174–1180. | ||

Kim HS, Lee J, Yi SY, Sy Y, et al. Liposarcoma: exploration of clinical prognostic factors for risk based stratification of therapy. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:205. | ||

Youden WJ. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer. 1950;3(1):32–35. | ||

Yamagishi T, Fujimoto N, Nishi H, et al. Prognostic significance of the lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. Lung Cancer. 2015;90(1):111–117. | ||

Mano Y, Yoshizumi T, Yugawa K, et al. Lymphocyte-to-Monocyte Ratio is a Predictor of Survival after Liver Transplantation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Liver Transpl. 2018. Epub 2018 Jun 12. | ||

Lieto E, Galizia G, Auricchio A, et al. Preoperative Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio and Lymphocyte to Monocyte Ratio are Prognostic Factors in Gastric Cancers Undergoing Surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2017;21(11):1764–1774. | ||

Lin EY, Pollard JW. Role of infiltrated leucocytes in tumour growth and spread. Br J Cancer. 2004;90(11):2053–2058. | ||

Hoffmann TK, Dworacki G, Tsukihiro T, et al. Spontaneous apoptosis of circulating T lymphocytes in patients with head and neck cancer and its clinical importance. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8(8):2553–2562. | ||

Mlecnik B, Tosolini M, Kirilovsky A, et al. Histopathologic-based prognostic factors of colorectal cancers are associated with the state of the local immune reaction. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(6):610–618. | ||

Stotz M, Pichler M, Absenger G, et al. The preoperative lymphocyte to monocyte ratio predicts clinical outcome in patients with stage III colon cancer. Br J Cancer. 2014;110(2):435–440. | ||

Balkwill F, Charles KA, Mantovani A. Smoldering and polarized inflammation in the initiation and promotion of malignant disease. Cancer Cell. 2005;7(3):211–217. | ||

Tsutsui S, Yasuda K, Suzuki K, et al. Macrophage infiltration and its prognostic implications in breast cancer: the relationship with VEGF expression and microvessel density. Oncol Rep. 2005;14(2):425–431. | ||

Balkwill F. Cancer and the chemokine network. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(7):540–550. | ||

Tseng WW, Malu S, Zhang M, et al. Analysis of the intratumoral adaptive immune response in well differentiated and dedifferentiated retroperitoneal liposarcoma. Sarcoma. 2015;2015:9. | ||

Dieu-Nosjean MC, Antoine M, Danel C, et al. Long-term survival for patients with non-small-cell lung cancer with intratumoral lymphoid structures. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(27):4410–4417. | ||

Coppola D, Nebozhyn M, Khalil F, et al. Unique ectopic lymph node-like structures present in human primary colorectal carcinoma are identified by immune gene array profiling. Am J Pathol. 2011;179(1):37–45. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.