Back to Journals » Journal of Inflammation Research » Volume 16

Potential Implications of Hyperoside on Oxidative Stress-Induced Human Diseases: A Comprehensive Review

Authors Wang K, Zhang H, Yuan L, Li X, Cai Y

Received 15 May 2023

Accepted for publication 27 September 2023

Published 13 October 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 4503—4526

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JIR.S418222

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Ning Quan

Kaiyang Wang,1,* Huhai Zhang,2,* Lie Yuan,3,4 Xiaoli Li,3,4 Yongqing Cai1

1Department of Pharmacy, Daping Hospital, Army Medical University, Chongqing, People’s Republic of China; 2Department of Nephrology, Southwest Hospital, Army Medical University, Chongqing, People’s Republic of China; 3Department of Pharmacology, College of Pharmacy, Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing, People’s Republic of China; 4Chongqing Key Research Laboratory for Drug Metabolism, College of Pharmacy, Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing, People’s Republic of China

*These authors contributed equally to this work

Correspondence: Yongqing Cai, Department of Pharmacy, Daping Hospital, Army Medical University, No. 10 Changjiang Branch Road, Yuzhong District, Chongqing, 400042, People’s Republic of China, Tel +86 023 68746950, Email [email protected] Xiaoli Li, Department of Pharmacology, College of Pharmacy, Chongqing Medical University, No. 1 Yixueyuan Road, Yuzhong District, Chongqing, 400016, People’s Republic of China, Tel +86 023 63657050, Email [email protected]

Abstract: Hyperoside is a flavonol glycoside mainly found in plants of the genera Hypericum and Crataegus, and also detected in many plant species such as Abelmoschus manihot, Ribes nigrum, Rosa rugosa, Agrostis stolonifera, Apocynum venetum and Nelumbo nucifera. This compound exhibits a multitude of biological functions including anti-inflammatory, antidepressant, antioxidative, vascular protective effects and neuroprotective effects, etc. This review summarizes the quantification, original plant, chemical structure and property, structure–activity relationship, pharmacologic effect, pharmacokinetics, toxicity and clinical application of hyperoside, which will be significant for the exploitation for new drug and full utilization of this compound.

Keywords: hyperoside, original plant, chemical structure, pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, toxicity

Introduction

Humans have used plants as the basis of traditional medical system for many years.1 However, even with the rise of modern medicine, traditional medicine is being drawn upon. As the discovery and synthesis of traditional chemical drugs are facing great obstacles and challenges, more and more researchers have turned their attention to the application of natural drugs and their extracts.2,3 As the source of natural drugs often comes from plants, animals or other natural products,4,5 they always show a superiority in side effects, metabolic burden and other aspects compared with traditional chemical synthetic drugs.6,7 The research boom gained momentum after Tu Youyou was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2015. Different from the traditional chemical drugs, natural drugs and their extracts have been considered to be good resources for new drugs, especially in plants. Because of the wide variety of plants and extracts they have become the main resources of natural drugs.

With the further study of natural medicinal chemistry, the active components in plants and their natural extracts have been isolated and analyzed.8,9 After screening several dozen commonly-used natural herbs, many compounds from plant extracts are reported, which efficiently exhibited anti-inflammatory responses.10–14

While the flavonoids are one of the most important natural compounds including flavanones, isoflavones, etc. possess a multitude of biological effects including anti-bacteria, anti-inflammatory, anti-allergy, anti-oxidation,15,16 cytoprotective, anti-thrombotic and anti-platelet.17,18

With the development of natural medicinal chemistry, many natural compounds or drugs derived from natural compounds have used in clinic.19,20 For instance, paclitaxel has been used to treat ovarian, breast, and lung cancer,21 artemisinin has been used to treat malaria,22 and silibinin from Silybum marianum has been applied to treat hepatitis,23 etc.

Quercetin-3-O-β-D-galactopyranoside, known as hyperoside, is a flavonol glycoside mainly found in plants of the genera Hypericum and Crataegus,24 and also detected in many plant species such as Abelmoschus manihot, Ribes nigrum, Rosa rugosa, Agrostis stolonifera, Apocynum venetum and Nelumbo nucifera. This compound exhibits a multitude of biological functions including as an anti-inflammatory,25 antidepressant,26 antioxidative,27 a vascular protector,28 and neuroprotector.29

In this review we summarize the advancements of hyperoside from six aspects including quantification and original plant, chemical structure and property, structure–activity relationship, pharmacologic effect, pharmacokinetics, toxicity and clinical application, which will be significant for the exploitation for new drug and full utilization of this compound (Figure 1). Additionally, possible tendency and perspective for future investigations of hyperoside is also discussed in this review.

|

Figure 1 The outline of review. |

Extraction and Original Plant

Since 1960, hyperoside has been isolated from red osier dogwood (Cornus stolonifera Michx.). And with the further study of natural medicinal chemistry, many natural drugs have been found to contain flavonoids and hyperoside is one of the most important components. With the development of chromatographic analysis methods including column chromatography, high performance counter-current chromatography, principal component analysis, high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) has been widely used in quantification of hyperoside. At present HPLC is also the most commonly used extraction and identification method recorded in Chinese Pharmacopoeia.

There are a variety of herbal plants have been applied in the extraction of hyperoside like Crataegus pinnatifida Bunge (hawthorn), Fagopyrum tataricum (L.) Gaertn. (Common buckwheat), etc. And hyperoside could also extracted from different parts of plants. For example, the leaf of Crataegus pinnatifida Bunge (Hawthorn), Crataegus azarolus L., Maytenus royleana Cufod., Eschweilera nana Miers, Flaveria bidentis (L.) Kuntze and Arbutus unedo L. The seed of Cuscuta chinensis var. chinensis, Hypericum perforatum L. and Hypericum annulatum Moris. The flower or blossom of Hypericum reflexum L.f., Hypericum canariense L. and Hypericum grandifolium Choisy. The fruit or hull of Fagopyrum tataricum (L.) Gaertn. (Common Buckwheat), Crataegus pinnatifida Bunge (Hawthorn), Carpobrotus edulis (L.) N.E.Br. The root of Dioscorea esculenta (Lour.) Burkill (Sweet Potato), Eleutherococcus senticosus Maxim. And the plant or the aerial part of Hypericum hircinum subsp. majus (Aiton) N.Robson, Polygonum aviculare L., Hypericum ascyron L., Euphorbia characias subsp. wulfenii (Hoppe ex W.D.J.Koch) Radcl.-Sm. and Hypericum perforatum L. In this section, we summarized the isolated original plants in Table 1.

|

Table 1 Original Plants and Parts |

Chemical Structure and Property

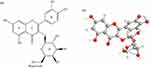

Hyperoside also called quercetin-3-O-β-D-galactoside pyranoside, belongs to flavonol glycosides. It’s composed of two phenyl rings (A and B rings), a six-membered oxygen heterocycle (C ring) and a galactopyranosid (D ring) (Figure 2a). With the deepening of research, Liu et al predicted the most stable conformation according to the minimum energy principle which is shown in Figure 2b, by calculating the Self-Consistent Field (SCF) energy level of twenty different chair and boat conformations of galactopyranosid (D ring).52

|

Figure 2 Structure and structure–activity of hyperoside. Chemical structural formula of hyperoside (a), Spatial structure diagram of hyperoside (b). |

It has been widely reported that hyperoside has a variety of bioactive functions, such as anti-bacteria, anti-inflammatory, anti-allergy, anti-oxidation, etc. The molecule of hyperoside contains lots of polar groups, including three ether bonds, one carbonyl group and eight hydroxyl groups. Based on its chemical structure these groups make hyperoside has high activity and could interact with multiple functional monomers.

Structure–Activity Relationship

Hyperoside as a kind of compound of flavonoids, due to its structure and properties exhibit some biological activity. Hyperoside could exhibit a variety of pharmacologic effects, based on its structure especially the substitutional groups.

The C2-3 double bond in C ring promotes the anti-cancer effects. And when there is a hydroxyl substituent(-OH) on the third carbon, the anti-cancer effects may be decreased.53 As aglycone of hyperoside is quercetin, they may have similar properties. And 5-OH also showed the same effect.53 On the contrary, 6-OH showed an enhancement on the anti-cancer effects, when the compound contains 3’,4’-OH the anti-cancer effect will be increased.54 Another factor that influences the anti-cancer effect is the differences of substituent.55

Meanwhile, hyperoside also has anti-oxidant effect, and the position of -OH is one of the most important factors,56 while hyperoside contains a 3’,4’-o-diphenol hydroxyl structure on B ring demonstrating the strong anti-oxidant effect. In addition, 5-OH and 7-OH also make hyperoside shows a strong anti-oxidant effect.57 And the double bond between C-2,3 has also been proved to be relative to the anti-oxidant.58

Pharmacologic Effect

Hyperoside is a biological active compound with great application prospect and there have been some clinical applications because of its effects in anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidative, anti-depressant and vascular protective effects and so on.59 So, in this part we reviewed the pharmacologic effects of hyperoside (Table 2, Figures 3 and 4).

|

Table 2 Pharmacologic Effects |

|

Figure 4 The possible molecular mechanisms of hyperoside in anti-cancer (breast, lung, pancreatic, skin, thyroid, renal, colon, liver, prostate and uterine). |

Anti-Oxidant Effect

Anti-oxidant effect is an essential effect of hyperoside. Several studies demonstrated that hyperoside showed a strong activity of anti-oxidant.97,143–146 In a model of oxidative damage induced by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), carbon tetrachloride and cadmium in Saccharomyces cerevisiae demonstrated that hyperoside could significantly increase cell viability, decrease the lipid peroxidation (LPO) and intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels.60 In human spermatozoa LPO model induced by H2O2, C. sativa leaf extract containing high concentration hyperoside showed great antioxidant effect by reducing LPO level. And hyperoside showed a protective effect on damage induced by LPO particularly at the plasma membrane level.61 In the tert-butyl hydroperoxide (TBHP) induced model, hyperoside could protect PC12 and ECV-304 cells against cytotoxicity induced by TBHP.62,63 In B16F10 melanoma cells (B16 cells), hyperoside was reported to suppress oxidative stress-induced melanogenesis.64,65

Radical scavenging activity and enhancement of antioxidant enzyme play an important role in the cellular and molecular mechanisms of hyperoside’s antioxidant effect. In Qi et al research that hyperoside could resist the oxidative stress and dysfunction induced by H2O2 in osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 via regulation of mitogen-activated proteinkinase (MAPK)-mediated responses.66 Hyperoside could also play an anti-oxidant effect in dopaminergic neurons induced by 6-hydroxydopamine (6-HODA) via activation of nuclear erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2)/heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) signaling.67 Xing et al reported hyperoside further enhanced the cellular antioxidant defense system through MAPK-dependent Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1)-Nrf2-antioxidant response element (ARE) signaling pathway to up-regulating HO-1 expression.68 In carbon tetrachloride-treated Wistar female rat, hyperoside extracted from Rourea induta Planch. (RIEE) was found to reduce histopathologic alterations observed in the liver and levels of oxidative stress markers.69 In H2O2-induced damage model in Chinese hamster fibroblast (V79-4) cells, hyperoside possessed cytoprotective properties against oxidative stress by scavenging intracellular ROS and enhancing anti-oxidant enzyme activity.70 Besides, Liu et al demonstrated hyperoside exhibited significant radical scavenging activation 1.1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical, hydroxyl radical and ABTS radical, respectively.27

Cardiovascular Protective Effect

Cardiovascular disease has gradually become a serious threat to human health. Many factors including inflammatory, play a very important role in the occurrence and progression of cardiovascular disease. Many studies have shown that hyperoside has a certain effect on the inhibition of cardiovascular related-disease.

As a vital organ to pump blood, heart is in need of a lot of oxygen and also most sensitive to lack of oxygen, so a hypoxic environment could cause damage to the cardiomyocytes even to the cardiovascular system, like coronary and cyanotic congenital heart disease.147 He et al conducted a study that hyperoside could perform a protective effect in hypoxic H9C2 cells cardiomyocytes. Meanwhile, they also found that hyperoside upregulated miR-138 expression levels and inhibited the downstream expression of mixed lineage kinase 3 (MLK3) and lipocalin-2 (Lcn2) to alleviate apoptosis to promote the survival of cardiomyocytes.71

It’s widely acknowledged that vascular endothelial cells play a pivotal role in maintaining normal cardiovascular system function.148 Hyperoside isolated from Acanthopanax chiisanensis Roots exhibited a significant inhibition effect in acetic acid-induced vascular permeability in vivo. And the inhibited effect might be relative with the inhibition of the production of prostaglandin E2 (PEG2) and NO in immune cells.72 Researchers also found that hyperoside could help to against the vascular endothelial injury induced by anticardiolipin antibody in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) via activating mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)-mediated autophagy.73 Hyperoside protected HUVECs against H2O2 damage, at least partially, by activating the extra cellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK) signaling pathway.74 Hyperoside suppressed vascular inflammatory processes induced by high glucose (HG) in HUVECs and in C57BL/6 mice.75 Besides, hyperoside suppressed lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-mediated release of High-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) and HMGB1-mediated cytoskeletal rearrangement.76

In vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) model, Huo et al reported hyperoside increased the expression of Nur77 (an orphan nuclear receptor) in rat VSMCs and inhibited VSMCs proliferation and the carotid artery ligation-induced neointimal formation.28 And hyperoside was found to exhibit the effects in preventing atherosclerosis via the oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL)-lectin-like oxLDL receptor-1 (LOX1)-ERK signal pathway to inhibit VSMC proliferation.77

Hyperoside produced significant hyperpolarization and relaxation in rat basilar artery smooth muscle cells through both endothelium-dependent and endothelium-independent mechanisms.78 Furthermore, in the myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury model in Sprague-Dawley rat hearts, hyperoside could protect cardiomyocytes from I/R-induced oxidative stress through the activation of ERK-dependent signaling.79

Myocardial infarction (MI) has a high morbidity in cardiovascular diseases. In a model conducted by a ligating surgery of the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery in KM mice, hyperoside obviously showed its protective effect on heart injury in MI mice. Furthermore, the protective effect may partial due to the up-regulation of autophagy and suppression of NLRP1 inflammation pathway.80 Cardiac hypertrophy is a condition leading to many cardiac diseases.149 The experiments in vitro and in vivo indicated that hyperoside could alleviate established cardiac remodeling and even prevent the occurrence of cardiac remodeling, via inhibition of protein kinase (AKT) pathway.81 In heart failure rats, hyperoside showed a protective effect via improving the cardiac function of heart failure, meanwhile hyperoside could also repress apoptosis and induce autophagy in H9C2 cells.82

Anti-Inflammatory

In the HT22 murine neuronal cell, hyperoside showed a protective effect in LPS-induced inflammatory model via the regulation of a series of inflammation-related molecules. For instance, the downregulation of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, etc. And the upregulation of the expression of catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD), reduced glutathione (GSH) and so on. Meanwhile the expression of silent mating type information regulation 2 homolog-1 (SIRT1) was also increased which is the key molecule to active Wnt/β-Catenin and Sonic Hedgehog pathways. All in all, hyperoside could alleviate LPS-induced HT22 murine neuronal cell inflammatory model by the activation of Wnt/β-Catenin and Sonic Hedgehog pathways via upregulating of SIRT1.83 In the LPS-stimulated rat peritoneal macrophages model, hyperoside isolated from the extract of Acanthopanax chiisanensis Nakai root was shown to inhibit nitric oxide (NO) production through inhibition of the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) by attenuation of p44/p42 MAPK, p38 MAPK and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK).84 Hyperoside is also reported to ameliorate the progression of osteoarthritis via the suppression of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT/NF-κB and the MAPK signaling pathways and the enhancement of Nrf2/HO-1.85 Hyperoside also could against the apoptosis and inflammatory in human renal proximal tubule (HK-2) cells exposed to high glucose via miR-499a-5p/nuclear receptor-interacting protein 1 (NRIP1) axis.86 Xu et al reported the therapeutic potential of hyperoside in periodontitis, and the activation of the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathway was considered to be the key point.87 And in the mouse peritoneal macrophages, hyperoside could inhibit the inflammation through the suppression of the activation of NF-κB signaling pathway.25

Antidepressant Effect

In C6 glioblastoma cell model, hyperoside from St. John’s Wort reduce β2-adrenergic sensitivity,88 and β1-adrenergic receptor density in the plasma membrane.89 Besides, Zheng et al reported hyperoside showed antidepressant effect in the corticosterone-induced neurotoxicity in PC12 cell, and the possible mechanisms is related to elevate BDNF and cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) through AC-cAMP-CREB signal pathway.90

In the study of Orzelska-Górka et al, the researchers conducted tail suspension test (TST) and forced swimming test (FST) on mice and confirmed that hyperoside could significantly reduce immobility, and had no effect to locomotor activity of mice. And the antidepressant effect was observed to be mediated by monoaminergic system and the upregulation of BDNF.91 In another FST on mice and rats, Hass et al found hyperoside (10 and 20 mg/kg i.p. in mice; 1.8 mg/kg/day P.O. in rats) presented a depressor effect on the central nervous system as well as an antidepressant-like effect which is mediated by the dopaminergic system.26 The antidepressant effect of hyperoside was also reported to be related to the serotoninergic system including 5-HT2A, 5-HT2 receptor.92 In a chronic unpredicted mild stress inducing depressive behavior rat model, hyperoside possessed antidepressant-like activity due to its antioxidant effect and regulation on hypothalamus- pituitary- adrenal (HPA) axis activity.93 In a reserpine injection-induced depressant model in mice, hyperoside from the total flavonoid in hypericumperforatum promoted the level of norepinephrine (NE) and 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HT) in brain and decreased the activity of monoamine oxidase (MAO) to display antidepressant-like effect.94

Neuroprotective Effect

A variety of neuroprotective effects of hyperoside has been confirmed in many studies. In Amyloid β-protein25-35 (Aβ25-35)-induced primary cultured cortical neurons, the neuroprotective effects of hyperoside were investigated. Hyperoside protected Aβ25-35-induced primary cultured cortical neurons via PI3K/Akt/Bad/Bclxl-regulated mitochondrial apoptotic pathway, suggesting hyperoside could be developed into a clinically valuable treatment for Alzheimer’s disease and other neuronal degenerative diseases associated with mitochondrial dysfunction.95 Hyperoside was found to significantly protect neurons from injury induced by reperfusion, while the mechanism may be associated to NO signaling pathway. That hyperoside could inhibit the activation of NF-κB to lessen the expression of iNOS, then ameliorated ERK, JNK and Bcl-2 family-related apoptotic signaling pathway.29 In the model of CoCl2-induced hypoxic/ischemic PC12 cells, hyperoside exhibited neuroprotective effects on hypoxic/ischemic neural injuries through inhibiting apoptosis.96

In vivo, hyperoside, isolated from Cortex Acanthopanacis Radicis, inhibited anti-acetyl-cholinesterase (AchE) activity and potently ameliorated scopolamine-induced memory impairment model in Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) mice. Additionally, the effect may be partially mediated by the acetylcholine-enhancing cholinergic nervous system.97 In a cerebral ischemia reperfusion model in rats, hyperoside was found to up-regulate the level of H2S to causes vasodilation against cerebral ischemia injury. And hyperoside could decreased the synthesis and release of NO to protect brain.98 And researchers also found hyperoside could help against the injury induced by cerebral ischemia reperfusion model in mice and the mechanism may be relative to the upregulation of cystathionine γ-lyase (CES)-H2S signal pathway.99 And further study elaborated the upregulation of H2S could activate KCa and opening KCa channels, leading to the hyperpolarization of VSMC membrane and block Ca2+ influx, then results in vasodilatation.100 Hyperoside could promote the anti-oxidant activity of SOD and CAT to alleviate oxidative stress injury, and contribute to attenuate memory impairment induced by hypobaric hypoxia in rats.101

Anti-Cancer Effects

Anti-Breast Cancer

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women around the world. In a recent study, Qiu et al found that hyperoside has an anti-breast cancer effect in vivo and in vitro. And they demonstrated that hyperoside could reduce the produce of ROS and the expression of Bcl-2 and X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (XIAP), resulting in the inhibition of the activation of NF-κB signal pathway to promote the apoptosis of breast cancer cell. Meanwhile the downregulation of ROS could also activate caspase-3 to promote apoptosis.102

As the traditional treatment facing great challenge, combination drug therapy seems to be a new treatment. Sun et al conducted a study to see if hyperoside could be used in combination drug therapy. Besides the anti-breast cancer effect, hyperoside could also attenuate paclitaxel-mediated anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 expression, meanwhile enhanced the expression of Bax. Hyperoside also reversed the toll-like receptor-4 (TLR4)-NF-κB signaling induced by paclitaxel. So hyperoside could enhance the sensitive of breast cancer cells to paclitaxel.103

Anti-Lung Cancer

Inflammatory has been proved to be an important response in the progress of cancers. Lü found that hyperoside induced apoptosis and suppressed inflammatory response in vivo and in vitro. The key point is the activation of caspase-3 to motivate apoptosis and inactivation of NF-κB to inhibit inflammatory.104 Hypoxia is an important factor in the survival and proliferation of lung cancer cells. In a A549 human non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell model, hyperoside could reverse the downregulation of phosphorylation of adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and expression of HO-1 induced by hypoxia.105 Hyperoside inhibited cell viability of A549 cells in a dose and time dependent-manner and upregulated apoptosis via activation of the p38 MAPK- and JNK-induced mitochondrial death pathway.106

As the activation of ROS could induced apoptosis, hyperoside upregulated ROS in A549 cells leading to the upregulation of p38 MAPK, caspase-3, caspase-9 and Bax. And all the effects above resulting in the promotion of apoptosis in lung cancer cells.107 In A549 cells, hyperoside combined with microRNA-let-7, a tumor suppressor, could perform a synergistic effect on anti-cancer. And the mechanism relative to induce apoptosis and inhibition of proliferation via blocking the process of G1/S phase.108 Hyperoside was confirmed to inhibit the proliferation and induce the apoptosis of T790M-positive NSCLC cells by upregulating the expression of fork head box protein O1 (FoxO1).109 Besides apoptosis, hyperoside could also inhibit Akt/mTOR/p70S6K signal pathway to induce autophagy in A549 cells to perform an anti-cancer effect.110 Another study demonstrated that hyperoside induced apoptosis and inhibited proliferation through caspase-3 and p53 signal pathway to show a preventive effect on lung cancer cells.111

Migration and invasion are the important factors of the poor prognosis of malignancies including NSCLC. Hyperoside could also inhibit the migration and invasion of A549 cells via upregulating PI3K/Akt and p38 MAPK pathways.112

In a H466 human small cell lung cancer (SCLC) cells, hyperoside also exhibited an inhibition effect of cell viability by the activation of ROS/p38 MAPK pathway to promote the apoptosis of cancer cells.107

Anti-Pancreatic Cancer

Pancreatic cancer is the fourth leading cause of death relative to cancer. Boukes, G. J et al primarily proved that hyperoside could be a potential anti-pancreatic cancer drug.107,150 Hyperoside exhibited an effect in inhibiting proliferation and promoting apoptosis in PANC-1 and BxPC-3 cell lines and also inhibited the growth of tumor in vivo. Mechanically, the anti-cancer effect may be associated with the upregulation of Bax/Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL and down-regulation of NF-κB level and the downstream gene expression.113

Anti-Osteocarcinoma

The effects of hyperoside in osteosarcoma cells have been investigated. Hyperoside isolated from Abelmoschus manihot L. alleviated the progression of multiple myeloma in mouse model. The mechanism was found to be relative to the osteoblast genesis by inducing the differentiation of murine pre-osteoblast cells.114 In another model in vitro, hyperoside inhibited the proliferation of osteosarcoma cells by inducing G0/G1 arrest, without causing obvious cell death. Additionally, hyperoside may stimulates osteoblastic differentiation in osteosarcoma cells.115

Anti-Uterine Cancer

Gou et al demonstrated that hyperoside could inhibit proliferation of cervical cancer cells (Hela cells and C-33A cells) by downregulation of C-MYC gene expression.116 Li et al reported hyperoside may play an important role in tumor growth suppression with IC50 value was 38.67 μg/mL after 72 h treatment, 47.82 μg/mL after 48 h, and 69.14 μg/mL after 24 h, respectively. The inhibition may be associated with Ca2+-related mitochondrion apoptotic pathway in RL952 cells.117 Cisplatin is a traditional chemotherapy drug in many cancers including ovarian cancer. But drug resistance is a great challenge for cisplatin. Hyperoside induced apoptosis via the progesterone receptor membrane component 1 (PGRMC1) dependent autophagy. And hyperoside could also sensitize the cell to cisplatin in PGRMC1 overexpressed cells.118

Anti-Liver Cancer

Sen et al’s study primarily demonstrated that hyperoside could inhibit the proliferation of HepG2 cells and arise the apoptosis and the mechanism may be associated to the activation of p53/Caspase signal pathway.119

Bone morphogenetic protein-7 (BMP-7) has been found to have an anti-cancer effect in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Hyperoside suppressed HepG2 cell proliferation by inhibiting BMP-7 dependent PI3K/Akt signal pathway to against HCC.120 Another study demonstrated that hyperoside inhibiting CHRH-7919 cells by the upregulation of caspase 3 and caspase 9 induced apoptosis in vitro and animal tumor in vivo.59

Anti-Skin Cancer

In 7.12 dimethylbenzanthracene and 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate induced skin cancer model, hyperoside exhibited an anti-cancer effect via the inhibition of PI3K/Akt/mTOR/p38MAPK signal pathway and activation of AMPK to inhibit cell proliferation and induced apoptosis and autophagy.121

Anti-Prostate Cancer

Hyperoside combined with quercetin which has a familiar structure of hyperoside could inhibit prostate cancer cells (PC3 cell) growth via the activation of caspase-3 and cleavage of poly (adenosine ribose) polymerase. Furthermore, hyperoside reduced the expression of prostate tumor-associated microRNAs including microRNA-21 to inhibit metastasis.122

Anti-Renal Cancer

In another study on renal cancer cells. Hyperoside combined with quercetin could inhibit 786-O cells via the downregulation of ROS to induce caspase-3 cleavage and PARP cleavage. Hyperoside could also decrease microRNA-27A and induce zinc finger protein ZBTB10 resulting in the downregulation of specificity protein (Sp) transcription factors including Sp1, Sp3 and Sp4 which overexpressed in cancer cells and inhibit 786-O cells.123

Anti-Colon Cancer

In the SW620 human colorectal cancer cell line, hyperoside from Zanthoxylum bungeanum leaves showed a significant anti-proliferation effect and induced apoptosis. The mechanism may be relative to the upregulation of p53 and p21.124

In HT-29 human colon cancer cells, hyperoside significantly decreased the cell viability in a dose- and time-dependent manner via the activation of mitochondria-dependent apoptotic pathway inhibition of colon cancer.125

Anti-Thyroid Cancer

Nowadays, the morbidity of thyroid cancer is increasing, so it is necessary to get an effective agent in treating thyroid cancer. In SW579 cells, a human thyroid squamous cell carcinoma cell line, apoptosis was induced by hyperoside in a dose-dependent manner. And hyperoside could upregulate the expression of Fas and FasL mRNA and downregulate survivin protein expression to induce apoptosis of cancer cells.126

Antiviral Activity

Duck hepatitis B virus (DHBV) infection model in human hepatoma HepG2.2.15 cell was established to examine anti-hepatitis B virus (HBV) effect of hyperoside extracted from Abelmoschus Manihot (L) medik. The data showed the inhibition rates of hyperoside (0.05 g/L) on HBeAg and HBsAg in the cells were 86.41% and 82.27% on day 8, respectively. Additionally, the DHBV-DNA levels significantly decreased in the treatment of 0.05 g/kg/d and 0.10 g/kg/d of hyperoside. These results suggest hyperoside possess the anti-HBV effect in vitro and in vivo.127 Besides, hyperoside isolated from ethanol extract of Geranium carolinianum L. also exhibited anti-HBV effects in HepG2.2.15 cell.128 Nymphaea alba L. extract in which contains hyperoside showed an anti-hepatitis C virus activity in Huh-7 cell line.129

Hepatoprotective effect

In a N-acetyl-para-amino-phenol (APAP)-induced acute hepatic injury, hyperoside could activate Nrf2 to downregulate LDH and ALT to protect L02 cells.130 As Nrf2 was considered to be important in treatment of acute hepatic injury, exogenous BTB-CNC homolog 1 (Bach1) is an important molecule that regulates Nrf2 pathway. Researchers found hyperoside performed a hepatoprotective effect based on the improvement of Bach1 nuclear export, depending on ERK1/2-Crm1 to upregulate the level of Nrf2 binding to ARE.131 In vivo, hyperoside showed a protective effect against CCl4-induced acute liver injury in ICR mice. The protective effect may be due to enhancement of the antioxidative defense system and suppression of the inflammatory response.132 Kalegari et al showed Rourea induta Planch (RIEE) exhibits antioxidant and hepatic protective activities in vivo, which may be related to hyperoside (flavonoids composition of RIEE).69 Xing et al have conducted research both in vivo and in vitro demonstrating that hyperoside showed a protective effect in CCl4 induced rat liver injury model. Hyperoside could reverse the decrease of SOD and the upregulation of MAD. Hyperoside could protect against oxidative stress-induced liver injury via the PHLPP2-AKT-GSK-3β signaling pathway.133

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a metabolic disease and there is no medication for it. Sun et al proved that hyperoside performed a protective effect in NAFLD induced by high-fat diet (HFD). After treated with hyperoside, hepatic steatosis, insulin resistance, and inflammatory responses were significantly ameliorated. And the protective effect of hyperoside could be relative to the upregulation of Nr4A1 and leading to macrophage polarization.134

Liver is an organ with abundant blood supply, and heart failure was reported to lead to a liver injury and finally may result in a liver fibrosis. Gou et al found that hyperoside could correct heart failure and improve the liver fibrosis and injury in aortocaval fistula model (ACF) in rats. And the mechanism was proved to be associated with the inhibition of TGF-β1/Smad pathway.135

Other Pharmacological Effects

Allergic Reactions

The regulation of thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) levels in human mast cell line-1 (HMC-1) cells by hyperoside was investigated. TSLP plays an important role in the pathogenesis of allergic reactions. The results showed hyperoside significantly decreased production and mRNA expression of TSLP and the level of intracellular calcium, receptor-interacting protein 2 (RIP2), active caspase-1, NF-κB, IL-1β and IL-6 in stimulated HMC-1 cells. In conclusion, these investigations establish hyperoside as a potential agent for the treatment of allergic reactions.136 Flavonoids including hyperoside could covalent modify bovine β-lactoglobulin (BLG), so as to alters human intestinal microbiota, might result in the reduction of allergenicity.137

Anticoagulant activity

The potential anticoagulant activities of hyperoside from Oenanthe javanica, were tested in HUVECs. As results showed, hyperoside significantly prolonged APTT and PT and inhibition of the activities of thrombin and FXa, and inhibited production of thrombin and FXa in HUVECs. The report indicates hyperoside possesses antithrombotic activities and offer bases for development of a novel anticoagulant.138

Antidiarrheal Activity

In an experiment, treatment of standardized ethyl acetate fraction of Rhododendron arboreum (EFRA) flowers (the concentration of hyperoside was found to be 0.148%) at 100, 200 and 400 mg/kg exhibited dose-dependent and significant antidiarrheal potential in castor oil and magnesium sulfate-induced diarrhea. Moreover, EFRA at doses of 100, 200 and 400 mg/kg also produced significant dose-dependent reduction in propulsive movement in castor oil-induced gastrointestinal transit using charcoal meal in rats. These results demonstrate that hyperoside has potent antidiarrheal activity for the treatment of diarrhea.151

Antifungal Activity

The camptothecin (CPT), trifolin and hyperoside isolated from amptotheca effectively control fungal pathogens in vitro, including Alternaria alternata, Epicoccum nigrum, Pestalotia guepinii, Drechslera sp., and Fusarium avenaceum. The flavonoids (trifolin and hyperoside) were less effective than CPT at 50 μg/mL, particularly within 20 days after treatment, but more effective at 100 or 150 μg/mL. These investigations showed hyperoside possessed potential antifungal activity.152 Extracts from Hypericum hircinum subsp.majus Exert showed an antifungal effects and further study demonstrated that hyperoside from the extract plays an important part in the antifungal effect.34

Herb-Drug Inhibitory Effect

In vitro, the potential herb-drug inhibitory effects of hyperoside on nine cytochrome P450 (CYP) isoforms in pooled human liver microsomes (HLMs) was investigated. Hyperoside strongly inhibited CYP2D6-catalyzed dextromethorphan O-demethylation, with IC50 values of 1.2 and 0.81 μM after 0 and 15 min of preincubation, and a Ki value of 2.01 μM in HLMs, respectively. In addition, hyperoside decreased CYP2D6-catalyzed dextromethorphan O-demethylation activity of human recombinant cDNA-expressed CYP2D6, with an IC50 value of 3.87 μM. However, other CYPs were not inhibited significantly by hyperoside. As data showed, hyperoside is a potent selective CYP2D6 inhibitor in HLMs, and might cause herb-drug interactions when co-administrated with CYP2D substrates.139

Treat Chronic Kidney Disease

Quercetin and hyperoside treatment (20 mg/kg/day) possess an inhibitory effect on the deposition of calcium oxalate (CaOx) formation in ethylene glycol (EG)-fed rats and might have an prevent effect for stone-forming disease.140 Diabetes is a kind of metabolism disease and has been proved to induce a renal injury. Osteomeles schwerinae Extract was found to prevent diabetes, in which hyperoside was found to be the biological activate compound. In diabetic rats’ model, hyperoside inhibited the platelet-derived growth factor-BB (PDGF-BB)/platelet-derived growth factor-B receptor (PDGFR-β) ligand binding.141 In a D-galactose induced renal aging and injury model, hyperoside was significantly useful in treating renal aging and injury. Further study demonstrated that hyperoside could attenuated renal aging and injury via inhibiting AMPK-autophagy activating kinase 1 (ULK1)-associated autophagy.142

Antinociceptive Effect

According to a study, aqueous extract of Roureainduta has significant antinociceptive action, which seems to be associated with an inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokines activated pathways. Hyperoside was isolated from aqueous extract of Roureainduta and may be responsible for its effect.153 Periaqueductal gray (PAG) is a structure plays an important role in pain transmission and modulation. Research found that noxious stimuli enhanced the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) expression in the PAG. Hyperoside isolated from Rhododendron ponticum L. significantly reversed up-regulation of NR2B-containing NMDAR in PAG and showed an antinociceptive effect in a persistent inflammatory stimulus.154 In research about the acute inflammatory pain model, hyperoside could exhibit an inhibition on the pain induced by acute inflammatory models.155

Pharmacokinetics

In the experiment conducted by Wu et al, HPLC was applied to analyze the pharmacokinetic behavior of hyperoside isolated from hawthorn leaf. The results demonstrated that after intravenous administration, the hyperoside presented a 3 rooms model. And the absorption and elimination of hyperoside was fast as the hyperoside could be detected 3 min after administration, and eliminated in 2 h.156 Ai et al carried out another experiment to study the absorption, distribution and excretion of hyperoside after intragastric administration to rats. The results revealed that hyperoside was absorbed rapidly after intragastric administration with a long half-life of about 4 hours. And the absolute bioavailability was 26% demonstrating that hyperoside could be made into an oral preparation for clinical application.157 In Tan et al’s study showed the half-life of intravenous administration of hyperoside was 264.96±145.80 min detecting with LC/MS.158

Toxicity

Recently the application of natural drugs or the chemical drugs from natural product has become a hotspot, hyperoside has been proved to have many kinds of pharmacological effect, but the toxicity of hyperoside also need to be evaluated.

In research conducted in Wistar rats, the researchers demonstrated that in a long-term oral administration lasted for 6 months, hyperoside has a good safety. And the possible target organ of toxicity is kidney and the damage is reversible.159 Ai et al finished a further study in beagle dogs, the results indicated that hyperoside also had a good safety in a dog model. While in some individuals damage to liver and kidney was observed, suggesting liver and kidney could also be the target organ.160 When applied on healthy pregnant rats, the results showed that hyperoside in a dose of 1000 mg/kg influenced the body weight, the length of the embryos and the length of tail. The results suggested that hyperoside may do harm to the pregnant.161

Clinical Application

Hyperoside is a flavonoids compound isolated from many natural products, but it has not been used in clinical as a drug independently, so in this part we under view the medicinal materials or drugs that hyperoside was the main biological active compound or play an important part in the process in which drugs function. Hypericum perforatum L. what is also call St. John’s wort has effects in anti-virus, anti-inflammatory, diuretic therapy and so forth and has been applied as a drug of first choice in treating depressant.162 Dried rose petals from Rose damascene Mill. is a traditional medicine in Uyghur medicine, hyperoside is the main active compound. It has been used in neurasthenia, dizziness, brain distension, etc.163

At the same time, there are also many Chinese patent medicines containing hyperoside in the market widely used. Jianer Qingjie solution an oral preparation made up of Honeysuckle, chrysanthemum, forsythia, hawthorn, bitter almond, tangerine peel and so on, applied on cough, sore throat, loss of appetite, etc.164 Chaijin Jieyu granules, apreparation composed of six Chinese herbs including bupleurum, Hypericum perforatum, jujube seed, coptis, etc. was used to treat depressant.165 Qianbai Biyan Capsule used for stuffy nose, itching gas heat, runny nose yellow thick, or continuous stuffy nose, slow sense of smell, acute and chronic rhinitis, acute and chronic sinusitis, etc. And hyperoside is indicative component and the main ingredient of the preparation.166

Prospects and Conclusion

The last 200 years, based on the rapid development of chemistry, has brought us a new way to gain new drugs which is quite different from the ancient drug discovery that we can only gain drugs from natural plants, animals or mineral. With the help of chemistry, we can synthesize some of the new drugs that we need, or we can modify the structure of the existing drugs to get new drugs based on the pharmacological action of different pharmacophores. As the drug resistance and side effects of traditional chemical treatment has faced great challenges. So, natural medicine has gradually entered the vision of researchers, but the complex components of natural medicine has brought great obstacle to the pharmacologic effects clarification and drug quality control that made natural medicine has not been as widely used as traditional chemical medicine. With the development and progress of extraction and separation technology. It provides the foundation for the further research and application of natural medicine and natural monomeric drugs have become the focus of research.

Hyperoside as a member of the flavonoids is distributed in many plants including hawthorn, common buckwheat, etc. and abundant in content. Based on the structure of hyperoside, it showed a variety of bioactive effects especially anti-oxidant effect, anti-inflammatory and anti-allergy effects, etc. While the further studies suggested that hyperoside plays an important role in various cancer models, and its mechanism of action is also very diverse. Meanwhile, hyperoside also showed a long half-life for 4 hours and the safety experiments also proves that it has good safety. All the results above indicated that hyperoside has broad application prospect.

However, the knowledge and systemic data is still incomplete and requires extensive research. Therefore, it is important to further investigate the pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, toxicity and molecular mechanisms of hyperoside based on modern concepts of diseases pathophysiology. Moreover, bioactivity-guided isolation and quantification of hyperoside and subsequent investigation of pharmacological effects will promote the development and wide the usage of this compound. Moreover, just like most natural drug monomers, hyperoside, due to its chemical properties, makes it a large gap in stability from traditional synthetic small molecule drugs, is also an important factor restricting the clinical use of many natural compounds. In addition, due to the lack of clinical application demand, there is a lack of research on the synthesis process of corresponding molecules, and relying on natural extraction alone is often difficult to meet the needs of large-scale application, which further limits the possibility of its clinical application.

Based on the problems above, hyperoside has not been made into a single drug for clinical application, only performed as an important active gradient in a drug which indicated that the application of hyperoside needs further study. Expanding this knowledge will make for a more practical application of hyperoside in medicine and society.

In addition to the application of hyperoside, we also have other gains from this review we believe that except constantly discovering new natural compounds, we can also improve the stability of existing potential drug molecules by means of multidisciplinary crossover, structural improvement, or preparation of certain dosage forms, so as to enhance their application prospects. So as to realize the transformation from laboratory to clinical application, so that our research results can benefit everybody.

Funding

This project is supported by a grant from the Chongqing Clinical Pharmacy Key Specialties Construction Project, Technology Project of Chongqing Health and Family Planning Commission (2019MSXM010) and Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing (No. cstc2020jcyj-msxmX0223).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Cragg GM, Newman DJ. Natural products: a continuing source of novel drug leads. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subjects. 2013;1830(6):3670–3695. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.02.008

2. Demir Y. Naphthoquinones, benzoquinones, and anthraquinones: molecular docking, ADME and inhibition studies on human serum paraoxonase‐1 associated with cardiovascular diseases. Drug Dev Res. 2020;81:628–636. doi:10.1002/ddr.21667

3. Demir Y, Durmaz L, Taslimi P, et al. Antidiabetic properties of dietary phenolic compounds: inhibition effects on α‐amylase, aldose reductase, and α‐glycosidase. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2019;66(5):781–786. doi:10.1002/bab.1781

4. Aslan HE, Demir Y, Özaslan MS, et al. The behavior of some chalcones on acetylcholinesterase and carbonic anhydrase activity. Drug Chem Toxicol. 2019;42(6):634–640. doi:10.1080/01480545.2018.1463242

5. Çağlayan C, Taslimi P, Demir Y, et al. The effects of zingerone against vancomycin‐induced lung, liver, kidney and testis toxicity in rats: the behavior of some metabolic enzymes. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2019;33:e22381. doi:10.1002/jbt.22381

6. Mahmudov I, Demir Y, Sert Y, et al. Synthesis and inhibition profiles of N-benzyl- and N-allyl aniline derivatives against carbonic anhydrase and acetylcholinesterase – a molecular docking study. Arab J Chem. 2022;15(3):103645. doi:10.1016/j.arabjc.2021.103645

7. Anil DA, Aydin BO, Demir Y, et al. Design, synthesis, biological evaluation and molecular docking studies of novel 1H-1,2,3-Triazole derivatives as potent inhibitors of carbonic anhydrase, acetylcholinesterase and aldose reductase. J Mol Struct. 2022;1257:132613. doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2022.132613

8. Ceylan H, Demir Y, Beydemir S. Inhibitory effects of Usnic and Carnosic Acid on some metabolic enzymes: an in vitro study. Protein Pept Lett. 2019;26:364–370. doi:10.2174/0929866526666190301115122

9. Demir Y, Ceylan H, Türkeş C, et al. Molecular docking and inhibition studies of vulpinic, carnosic and usnic acids on polyol pathway enzymes. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2022;40:12008–12021. doi:10.1080/07391102.2021.1967195

10. Persson PB, Persson AB. Age your garlic for longevity! Acta Physiol. 2012;205(1):1–2. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1716.2012.02424.x

11. Öztürk C, Bayrak S, Demir Y, et al. Some indazoles as alternative inhibitors for potato polyphenol oxidase. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2022;69(5):2249–2256. doi:10.1002/bab.2283

12. Özaslan MS, Sağlamtaş R, Demir Y, et al. Isolation of some phenolic compounds from plantago subulata L. and determination of their antidiabetic, anticholinesterase, antiepileptic and antioxidant activity. Chem Biodivers. 2022;19(8). doi:10.1002/cbdv.202200280

13. Bae J. Role of high mobility group box 1 in inflammatory disease: focus on sepsis. Arch Pharm Res. 2012;35(9):1511–1523. doi:10.1007/s12272-012-0901-5

14. Türkeş C, Demir Y, Beydemir Ş. In vitro inhibitory activity and molecular docking study of selected natural phenolic compounds as AR and SDH inhibitors. ChemistrySelect. 2022;7(48):e202204050. doi:10.1002/slct.202204050

15. Hollman P, Katan M. Absorption, metabolism of dietary flavonoids. Biomed&Pharmacother. 1997;51:305–310.

16. Rice-Evans CA, Miller NJ, Paganga G. Structure-antioxidant activity relationships of flavonoids and phenolic acids. Free Radic Biol Med. 1996;20(7):933–956. doi:10.1016/0891-5849(95)02227-9

17. Middleton EJ, Drzewiecki G. Flavonoid inhibition of human basophil histamine release stimulated by various agents. Biochem Pharmacol. 1984;33(21):3333–3338. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(84)90102-3

18. Mukaida N. Interleukin-8: an expanding universe beyond neutrophil chemotaxis and activation. Int J Hematol. 2000;72(4):391–398.

19. Palabıyık E, Sulumer AN, Uguz H, et al. Assessment of hypolipidemic and anti-inflammatory properties of walnut (Juglans regia) seed coat extract and modulates some metabolic enzymes activity in triton WR-1339-induced hyperlipidemia in rat kidney, liver, and heart. J Mol Recognit. 2023;36(3). doi:10.1002/jmr.3004

20. Bayrak S, Öztürk C, Demir Y, et al. Purification of polyphenol oxidase from potato and investigation of the inhibitory effects of phenolic acids on enzyme activity. Protein Pept Lett. 2020;27(3):187–192. doi:10.2174/0929866526666191002142301

21. Weaver BA, Bement W, Bement W. How Taxol/paclitaxel kills cancer cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2014;25(18):2677–2681. doi:10.1091/mbc.E14-04-0916

22. Yang J, He Y, Li Y, et al. Advances in the research on the targets of anti-malaria actions of artemisinin. Pharmacol Ther. 2020;216:107697. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107697

23. Federico A, Dallio M, Loguercio C. Silymarin/silybin and chronic liver disease: a marriage of many years. Molecules. 2017;22(2):191. doi:10.3390/molecules22020191

24. Zou Y, Lu Y, Wei D. Antioxidant activity of a flavonoid-rich extract of hypericum perforatum L. in vitro. J Agric Food Chem. 2004;52(16):5032–5039. doi:10.1021/jf049571r

25. Kim S, Um J-Y, Hong S-H, et al. Anti-Inflammatory activity of hyperoside through the suppression of nuclear factor-κB activation in mouse peritoneal macrophages. Am J Chin Med. 2012;39:171–181. doi:10.1142/S0192415X11008737

26. Haas JS, Dischkaln Stolz E, Heemann Betti A, et al. The anti-immobility effect of hyperoside on the forced swimming test in rats is mediated by the D2-like receptors activation. Planta Med. 2011;77(04):334–339. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1250386

27. Liu X, Zhu L, Tan J, et al. Glucosidase inhibitory activity and antioxidant activity of flavonoid compound and triterpenoid compound from agrimonia pilosa ledeb. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14(1):12. doi:10.1186/1472-6882-14-12

28. Huo Y, Yi B, Chen M, et al. Induction of Nur77 by hyperoside inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and neointimal formation. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014;92(4):590–598. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2014.09.021

29. Liu R, Xiong Q-J, Shu Q, et al. Hyperoside protects cortical neurons from oxygen–glucose deprivation–reperfusion induced injury via nitric oxide signal pathway. Brain Res. 2012;1469:164–173. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2012.06.044

30. Wang H, Hou X, Li B, et al. Study on active components of cuscuta chinensis promoting neural stem cells proliferation: bioassay-guided fractionation. Molecules. 2021;26(21):6634. doi:10.3390/molecules26216634

31. Yang L, Chen Q, Wang F, et al. Antiosteoporotic compounds from seeds of Cuscuta chinensis. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;135(2):553–560. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2011.03.056

32. Cui Y, Zhao Z, Liu Z, et al. Purification and identification of buckwheat hull flavonoids and its comparative evaluation on antioxidant and cytoprotective activity in vitro. Food Sci Nutr. 2020;8(7):3882–3892. doi:10.1002/fsn3.1683

33. Sun Y, Pan Z, Yang C, et al. Comparative assessment of phenolic profiles, cellular antioxidant and antiproliferative activities in ten varieties of sweet potato (Ipomoea Batatas) storage roots. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland). 2019;24(24):4476. doi:10.3390/molecules24244476

34. Tocci N, Perenzoni D, Iamonico D, et al. Extracts from hypericum hircinum subsp. majus exert antifungal activity against a panel of sensitive and drug-resistant clinical strains. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9. doi:10.3389/fphar.2018.00382

35. Wu P, Li F, Zhang J, et al. Phytochemical compositions of extract from peel of hawthorn fruit, and its antioxidant capacity, cell growth inhibition, and acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017;17(1). doi:10.1186/s12906-017-1662-y

36. Lund JA, Brown PN, Shipley PR. Quantification of North American and European Crataegus flavonoids by nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometry. Fitoterapia. 2020;143:104537. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2020.104537

37. Hafsa J, Hammi KM, Khedher MRB, et al. Inhibition of protein glycation, antioxidant and antiproliferative activities of Carpobrotus edulis extracts. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016;84:1496–1503. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2016.11.046

38. Mustapha N, Mokdad-Bzéouich I, Sassi A, et al. Immunomodulatory potencies of isolated compounds from Crataegus azarolus through their antioxidant activities. Tumor Biol. 2016;37(6):7967–7980. doi:10.1007/s13277-015-4517-5

39. Zorzetto C, Sánchez-Mateo CC, Rabanal RM, et al. Phytochemical analysis and in vitro biological activity of three hypericum species from the canary Islands (Hypericum reflexum, Hypericum canariense and Hypericum grandifolium). Fitoterapia. 2015;100:95–109. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2014.11.013

40. Shabbir M, Afsar T, Razak S, et al. Phytochemical analysis and Evaluation of hepatoprotective effect of Maytenus royleanus leaves extract against anti-tuberculosis drug induced liver injury in mice. Lipids Health Dis. 2020;19(1). doi:10.1186/s12944-020-01231-9

41. Cardoso ML, Bersani Amado C, Outuki,P, et al. A high performance liquid chromatography with ultraviolet method for Eschweilera nana leaves and their anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities. Pharmacogn Mag. 2015;11(43):619–626. doi:10.4103/0973-1296.160464

42. Mansur S, Abdulla R, Ayupbec A, et al. Chemical fingerprint analysis and quantitative analysis of Rosa rugosa by UPLC-DAD. Molecules. 2016;21(12):1754. doi:10.3390/molecules21121754

43. Xie Q, Ding L, Wei Y, et al. Determination of major components and fingerprint analysis of flaveria bidentis (L.) Kuntze. J Chromatogr Sci. 2014;52(3):252–257. doi:10.1093/chromsci/bmt020

44. Shen J, Yang K, Jiang C, et al. Development and application of a rapid HPLC method for simultaneous determination of hyperoside, isoquercitrin and eleutheroside E in Apocynum venetum L. and Eleutherococcus senticosus. BMC Chem. 2020;14(1). doi:10.1186/s13065-020-00687-1

45. Li L. Simulation determination of eight active components in Polygonum aviculare L. by HPLC. J Taishan Med Coll. 2021;42:61–65.

46. Wang H. Determination of 5 flavonoids in Hypericum ascyron L. by HPLC. Cent South Pharm. 2021;19:1911–1914.

47. Ozbilgin S, Acıkara ÖB, Akkol EK, et al. In vivo wound-healing activity of Euphorbia characias subsp. wulfenii: isolation and quantification of quercetin glycosides as bioactive compounds. J Ethnopharmacol. 2018;224:400–408. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2018.06.015

48. Dresler S, Kováčik J, Strzemski M, et al. Methodological aspects of biologically active compounds quantification in the genus Hypericum. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2018;155:82–90. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2018.03.048

49. Zeliou K, Kontaxis NI, Margianni E, et al. Optimized and Validated HPLC Analysis of St. John’s wort extract and final products by simultaneous determination of major ingredients. J Chromatogr Sci. 2017;55(8):805–812. doi:10.1093/chromsci/bmx040

50. Jia Q, Huang X, Yao G, et al. Pharmacokinetic study of thirteen ingredients after the oral administration of flos chrysanthemi extract in rats by UPLC-MS/MS. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:1–10. doi:10.1155/2020/8420409

51. Males Z, Saric D, Bojic M. Quantitative determination of flavonoids and chlorogenic acid in the leaves of arbutus unedo L. using thin layer chromatography. J Anal Methods Chem. 2013;2013:385473. doi:10.1155/2013/385473

52. Liu J, Zhang Z, Yang L, et al. Molecular structure and spectral characteristics of hyperoside and analysis of its molecular imprinting adsorption properties based on density functional theory. J Mol Graph Model. 2019;88:228–236. doi:10.1016/j.jmgm.2019.01.005

53. Cheng Y. Inhibition effect of nine flavonoids on human cancer cells and their structure-activity relationship analysis. Northwest Pharm J. 2014;29:187–190.

54. Chen J, Zhu Z-Q, Hu T-X, et al. Structure-activity relationship of natural flavonoids in hydroxyl radical scavenging effects. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2002;23:667–672.

55. Plochmann K, Korte G, Koutsilieri E, et al. Structure–activity relationships of flavonoid-induced cytotoxicity on human leukemia cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;460(1):1–9. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2007.02.003

56. Zhang Y, Wu X, Ding X. Studies on the relationship between the structure of flavonoids and their scavenging capacity on active oxygen radicals by means of chemiluminescence. Nat Prod Res Dev. 1998;10:26–33.

57. Zhao J. Study of 6 flavonoids compounds for the scavenging superoxide anion free radical ability and the structure-activity relationships. China Med Herald. 2014;11:7–10, 14.

58. Cai YZ, Sun M, Xing J, et al. Structure-radical scavenging activity relationships of phenolic compounds from traditional Chinese medicinal plants. Life Sci. 2006;78(25):2872–2888. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2005.11.004

59. Feng Y, Qin G, Chang S, et al. Antitumor effect of hyperoside loaded in charge reversed and mitochondria-targeted liposomes. Int J Nanomedicine. 2021;16:3073–3089. doi:10.2147/IJN.S297716

60. Gao Y, Fang L, Wang X, et al. Antioxidant activity evaluation of dietary flavonoid hyperoside using saccharomyces cerevisiae as a model. Molecules. 2019;24(4):788. doi:10.3390/molecules24040788

61. Biagi M, Noto D, Corsini M, et al. Antioxidant effect of the castanea sativa mill. Leaf extract on oxidative stress induced upon human spermatozoa. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019:8926075. doi:10.1155/2019/8926075

62. Liu Z, Tao X, Zhang C, et al. Protective effects of hyperoside (quercetin-3-o-galactoside) to PC12 cells against cytotoxicity induced by hydrogen peroxide and tert-butyl hydroperoxide. Biomed Pharmacother. 2005;59(9):481–490. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2005.06.009

63. Li HB, Yi X, Gao JM, et al. The mechanism of hyperoside protection of ECV-304 cells against tert-butyl hydroperoxide-induced injury. Pharmacology. 2008;82(2):105–113. doi:10.1159/000139146

64. Ohguchi K, Nakajima C, Oyama M, et al. Inhibitory effects of flavonoid glycosides isolated from the peel of Japanese persimmon (Diospyros kaki ‘Fuyu’) on melanin biosynthesis. Biol Pharm Bull. 2010;33:122–124. doi:10.1248/bpb.33.122

65. Kim YJ. Hyperin and quercetin modulate oxidative stress-induced melanogenesis. Biol Pharm Bull. 2012;35(11):2023–2027. doi:10.1248/bpb.b12-00592

66. Qi X, Li B, Wu WL, et al. Protective effect of hyperoside against hydrogen peroxide-induced dysfunction and oxidative stress in osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2020;48:377–383. doi:10.1080/21691401.2019.1709851

67. Kwon SH, Lee SR, Park YJ, et al. Suppression of 6-hydroxydopamine-induced oxidative stress by hyperoside via activation of Nrf2/HO-1 signaling in dopaminergic neurons. Int J Mol Sci. 2019. doi:10.3390/ijms20235832

68. Xing H, Liu Y, Chen J-H, et al. Hyperoside attenuates hydrogen peroxide-induced L02 cell damage via MAPK-dependent Keap1-Nrf2-ARE signaling pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;410:759–765. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.06.046

69. Kalegari M, Gemin CAB, Araújo-Silva G, et al. Chemical composition, antioxidant activity and hepatoprotective potential of Rourea induta Planch. (Connaraceae) against CCl4-induced liver injury in female rats. Nutrition. 2014;30(6):713–718. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2013.11.004

70. Piao MJ, Kang KA, Zhang R, et al. Hyperoside prevents oxidative damage induced by hydrogen peroxide in lung fibroblast cells via an antioxidant effect. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subjects. 2008;1780(12):1448–1457. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2008.07.012

71. He S, Yin X, Wu F, et al. Hyperoside protects cardiomyocytes against hypoxiainduced injury via upregulation of microRNA138. Mol Med Rep. 2021;23. doi:10.3892/mmr.2021.11925

72. Lee S, Jung SH, Lee YS, et al. Antiinflammatory activity of hyperin from Acanthopanax chiisanensis roots. Arch Pharm Res. 2004;27:628–632. doi:10.1007/BF02980162

73. Wei A, Xiao H, Xu G, et al. Hyperoside protects human umbilical vein endothelial cells against anticardiolipin antibody-induced injury by activating autophagy. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11. doi:10.3389/fphar.2020.00762

74. Li Z, Liu J-C, Hu J, et al. Protective effects of hyperoside against human umbilical vein endothelial cell damage induced by hydrogen peroxide. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;139(2):388–394. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2011.11.020

75. Ku S, Kwak S, Kwon O-J, et al. Hyperoside inhibits high-glucose-induced vascular inflammation in vitro and in vivo. Inflammation. 2014;37(5):1389–1400. doi:10.1007/s10753-014-9863-8

76. Ku S, Zhou W, Lee W, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of hyperoside in human endothelial cells and in mice. Inflammation. 2015;38(2):784–799. doi:10.1007/s10753-014-9989-8

77. Zhang Z, Zhang D, Du B, et al. Hyperoside inhibits the effects induced by oxidized low-density lipoprotein in vascular smooth muscle cells via oxLDL-LOX-1-ERK pathway. Mol Cell Biochem. 2017;433(1–2):169–176. doi:10.1007/s11010-017-3025-x

78. Fan Y, Chen Z-W, Guo Y, et al. Cellular mechanisms underlying Hyperin-induced relaxation of rat basilar artery. Fitoterapia. 2011;82(4):626–631. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2011.01.023

79. Li Z, Hu J, Li Y-L, et al. The effect of hyperoside on the functional recovery of the ischemic/reperfused isolated rat heart: potential involvement of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 signaling pathway. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;57:132–140. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.12.023

80. Yang Y, Li J, Rao T, et al. The role and mechanism of hyperoside against myocardial infarction in mice by regulating autophagy via NLRP1 inflammation pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. 2021;276:114187. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2021.114187

81. Wang X, Liu Y, Xiao L, et al. Hyperoside protects against pressure overload-induced cardiac remodeling via the AKT signaling pathway. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;51(2):827–841. doi:10.1159/000495368

82. Guo X, Zhang Y, Lu C, et al. Protective effect of hyperoside on heart failure rats via attenuating myocardial apoptosis and inducing autophagy. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2020;84(4):714–724. doi:10.1080/09168451.2019.1685369

83. Huang J, Zhou L, Chen J, et al. Hyperoside attenuate inflammation in HT22 cells via upregulating SIRT1 to activities Wnt/β-catenin and sonic hedgehog pathways. Neural Plast. 2021;2021:1–10. doi:10.1155/2021/8706400

84. Lee S, Park HS, Notsu Y, et al. Effects of hyperin, isoquercitrin and quercetin on lipopolysaccharide-induced nitrite production in rat peritoneal macrophages. Phytother Res. 2008;22:1552–1556. doi:10.1002/ptr.2529

85. Sun K, Luo J, Jing X, et al. Hyperoside ameliorates the progression of osteoarthritis: an in vitro and in vivo study. Phytomedicine. 2021;80:153387. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2020.153387

86. Zhou J, Zhang S, Sun X, et al. Hyperoside Protects HK-2 cells against high glucose-induced apoptosis and inflammation via the miR-499a-5p/NRIP1 pathway. Pathol Oncol Res. 2021;27. doi:10.3389/pore.2021.629829

87. Xu T, Wu X, Zhou Z, et al. Hyperoside ameliorates periodontitis in rats by promoting osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs via activation of the NF‐κB pathway. FEBS Open Bio. 2020;10:1843–1855. doi:10.1002/2211-5463.12937

88. Prenner L, Sieben A, Zeller K, et al. Reduction of high-affinity β 2-adrenergic receptor binding by hyperforin and hyperoside on rat C6 Glioblastoma cells measured by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2007;46:5106–5113. doi:10.1021/bi6025819

89. Jakobsa D, Hage-Hülsmann A, Prenner L, et al. Downregulation of b1-adrenergic receptors in rat C6 glioblastoma cells by hyperforin and hyperoside from St John’s wort. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2013;65:907–915. doi:10.1111/jphp.12050

90. Zheng M, Liu C, Pan F, et al. Antidepressant-like effect of hyperoside isolated from Apocynum venetum leaves: possible cellular mechanisms. Phytomedicine. 2012;19:145–149. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2011.06.029

91. Orzelska-Górka J, Szewczyk K, Gawrońska-Grzywacz M, et al. Monoaminergic system is implicated in the antidepressant-like effect of hyperoside and protocatechuic acid isolated from Impatiens glandulifera Royle in mice. Neurochem Int. 2019;128:206–214. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2019.05.006

92. Zhu ZM, Fan YJ, Pan Y, et al. Studies on the antidepressant-like effect of hyperoside on the possible mechanism of 5-HT system. J Changchun Normal Univ. 2018;37:83–87.

93. Yan Z, Chen-chen Z. Effect of hyperin on depressive behavior of rats induced by chronic unpredicted mild stress. Chin J New Drugs Clin Rem. 2017;36:150–156.

94. Li X, Wei CE, Zhao MB, et al. Experimental study of the total flavonoid in Hypericum perforatum on depression. China J Chin Mater Med. 2005;30:1184–1188.

95. Zeng K, Wang X-M, Ko H, et al. Hyperoside protects primary rat cortical neurons from neurotoxicity induced by amyloid β-protein via the PI3K/Akt/Bad/BclXL-regulated mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;672(1–3):45–55. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.09.177

96. Zeng K, Wang X, Fu H, et al. Protective effects and mechanism of hyperin on CoCl2-induced PC12 cells. China J Chin Mater Med. 2011;36:2409–2412.

97. Nam Y, Lee D. Ameliorating effects of constituents from cortex acanthopanacis radicis on memory impairment in mice induced by scopolamine. J Trad Chin Med. 2014;34(1):57–62. doi:10.1016/S0254-6272(14)60055-8

98. Han J. Mechanism of hyperoside- induced dilatation in middle cerebral arteries of rats subjected to cerebral ischemia reperfusion. Chin Pharm J. 2015;50:595–601.

99. Shanshan G, Shuo C, Zhiwu C. The H2S mechanism of Hyp against cerebral ischemia reperfusion injury in mice. Acta Univ Med Anhui. 2016;51:1292–1296.

100. Han J, Xuan JL, Hu HR, et al. Effects and mechanisms of hyperoside on vascular endothelium function in middle cerebral arteries of rats ex vivo. China J Chin Mater Med. 2014;39:4849–4855.

101. Jin-song L, Jian-hong C, Min-jie M. Hyperoside attenuated hypoxia-induced memory impairment by antioxidative activity. J Reg Anat Oper Surg. 2015;24:181–184.

102. Qiu J, Zhang T, Zhu X, et al. Hyperoside induces breast cancer cells apoptosis via ROS-Mediated NF-κB signaling pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:131. doi:10.3390/ijms21010131

103. Sun T, Liu Y, Li M, et al. Administration with hyperoside sensitizes breast cancer cells to paclitaxel by blocking the TLR4 signaling. Mol Cell Probes. 2020;53:101602. doi:10.1016/j.mcp.2020.101602

104. Lü P. Inhibitory effects of hyperoside on lung cancer by inducing apoptosis and suppressing inflammatory response via caspase-3 and NF-κB signaling pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016;82:216–225. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2016.05.006

105. Chen D, Wu Y-X, Qiu Y-B, et al. Hyperoside suppresses hypoxia-induced A549 survival and proliferation through ferrous accumulation via AMPK/HO-1 axis. Phytomedicine. 2020;67:153138. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2019.153138

106. Yang Y, Tantai J, Sun Y, et al. Effect of hyperoside on the apoptosis of A549 human non-small cell lung cancer cells and the underlying mechanism. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16(5):6483–6488. doi:10.3892/mmr.2017.7453

107. Jia X, Zhang Q, Xu L, et al. Lotus leaf flavonoids induce apoptosis of human lung cancer A549 cells through the ROS/p38 MAPK pathway. Biol Res. 2021;54(1). doi:10.1186/s40659-021-00330-w

108. Li J, Liao XH, Xiang Y, et al. Hyperoside and let-7a-5p synergistically inhibits lung cancer cell proliferation via inducing G1/S phase arrest. Gene. 2018;679:232–240. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2018.09.011

109. Hu Z, Zhao P, Xu H. Hyperoside exhibits anticancer activity in nonsmall cell lung cancer cells with T790M mutations by upregulating FoxO1 via CCAT1. Oncol Rep. 2020;43:617–624. doi:10.3892/or.2019.7440

110. Fu T, Wang L, Jin XN, et al. Hyperoside induces both autophagy and apoptosis in non-small cell lung cancer cells in vitro. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2016;37:505–518. doi:10.1038/aps.2015.148

111. Liu Y, Liu G-H, Mei JJ, et al. The preventive effects of hyperoside on lung cancer in vitro by inducing apoptosis and inhibiting proliferation through Caspase-3 and P53 signaling pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016;83:381–391. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2016.06.035

112. Yang Y, Sun Y, Guo X, et al. Hyperoside inhibited the migration and invasion of lung cancer cells through the upregulation of PI3K/AKT and p38 MAPK pathways. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2017;10:9382–9390.

113. Li Y, Wang Y, Li L, et al. Hyperoside induces apoptosis and inhibits growth in pancreatic cancer via Bcl-2 family and NF-κB signaling pathway both in vitro and in vivo. Tumor Biol. 2016;37(6):7345–7355. doi:10.1007/s13277-015-4552-2

114. Hou J, Qian J, Li Z, et al. Bioactive compounds from abelmoschus manihot L. alleviate the progression of multiple myeloma in mouse model and improve bone marrow microenvironment. OncoTargets and Therapy. 2020;13:959–973. doi:10.2147/OTT.S235944

115. Zhang N, Ying M-D, Wu Y-P, et al. Hyperoside, a flavonoid compound, inhibits proliferation and stimulates osteogenic differentiation of human osteosarcoma cells. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e98973. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0098973

116. Guo W, Yu H, Zhang L, et al. Effect of hyperoside on cervical cancer cells and transcriptome analysis of differentially expressed genes. Cancer Cell Int. 2019;19(1). doi:10.1186/s12935-019-0953-4

117. Li F, Yu F-X, Yao S-T, et al. Hyperin extracted from Manchurian rhododendron leaf induces apoptosis in human endometrial cancer cells through a mitochondrial pathway. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13(8):3653–3656. doi:10.7314/APJCP.2012.13.8.3653

118. Zhu X, Ji M, Han Y, et al. PGRMC1-dependent autophagy by hyperoside induces apoptosis and sensitizes ovarian cancer cells to cisplatin treatment. Int J Oncol. 2017;50(3):835–846. doi:10.3892/ijo.2017.3873

119. Jiang S, Xiong HS, Wu HK, et al. Regulatory effect of hyperoside on proliferation and apoptosis of hepatic carcinoma cell HepG2 via mitochondrial P53 /Caspase signaling pathway. Chin J Immunol. 2018;34:1832–1836.

120. Wei S, Sun Y, Wang L, et al. Hyperoside suppresses BMP-7-dependent PI3K/AKT pathway in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9(15):1233. doi:10.21037/atm-21-2980

121. Kong Y, Sun W, Wu P. Hyperoside exerts potent anticancer activity in skin cancer. Front Biosci. 2020;25(3):463–479. doi:10.2741/4814

122. Yang F, Liu M, Li W, et al. Combination of quercetin and hyperoside inhibits prostate cancer cell growth and metastasis via regulation of microRNA-21. Mol Med Rep. 2015;11(2):1085–1092. doi:10.3892/mmr.2014.2813

123. Li W, Liu M, Xu Y-F, et al. Combination of quercetin and hyperoside has anticancer effects on renal cancer cells through inhibition of oncogenic microRNA-27a. Oncol Rep. 2014;31(1):117–124. doi:10.3892/or.2013.2811

124. Zhang Y, Dong H, Zhang J, et al. Inhibitory effect of hyperoside isolated from Zanthoxylum bungeanum leaves on SW620 human colorectal cancer cells via induction of the p53 signaling pathway and apoptosis. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16(2):1125–1132. doi:10.3892/mmr.2017.6710

125. Guon TE, Chung HS. Hyperoside and rutin of Nelumbo nucifera induce mitochondrial apoptosis through a caspase-dependent mechanism in HT-29 human colon cancer cells. Oncol Lett. 2016;11(4):2463–2470. doi:10.3892/ol.2016.4247

126. Liu Z, Liu G, Liu X, et al. The effects of hyperoside on apoptosis and the expression of Fas/FasL and survivin in SW579 human thyroid squamous cell carcinoma cell line. Oncol Lett. 2017;14(2):2310–2314. doi:10.3892/ol.2017.6453

127. Wu L, Yang X-B, Huang ZM, et al. In vivo and in vitro antiviral activity of hyperoside extracted from Abelmoschus manihot (L) medik1. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2007;28(3):404–409. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7254.2007.00510.x

128. Li J, Huang H, Zhou W, et al. Anti-hepatitis B virus activities of Geranium carolinianum L. extracts and identification of the active components. Biol Pharm Bull. 2008;31(4):743–747. doi:10.1248/bpb.31.743

129. Rehmana S, Ashfaq UA, Ijaz B, et al. Anti-hepatitis C virus activity and synergistic effect of Nymphaea alba extracts and bioactive constituents in liver infected cells. Microb Pathog. 2018;121:198–209. doi:10.1016/j.micpath.2018.05.023

130. Jiang Z, Wang J, Liu C, et al. Hyperoside alleviated N-acetyl-para-amino-phenol-induced acute hepatic injury via Nrf2 activation. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2019;12(1):64–76.

131. Cai Y, Li B, Peng D, et al. Crm1-dependent nuclear export of bach1 is involved in the protective effect of hyperoside on oxidative damage in hepatocytes and CCl4-induced acute liver injury. J Inflamm Res. 2021;14:551–565. doi:10.2147/JIR.S279249

132. Choi J, Kim D-W, Yun N, et al. Protective effects of hyperoside against carbon tetrachloride-induced liver damage in mice. J Nat Prod. 2011;74(5):1055–1060. doi:10.1021/np200001x

133. Xing H, Fu R, Cheng C, et al. Hyperoside protected against oxidative stress-induced liver injury via the PHLPP2-AKT-GSK-3β signaling pathway in vivo and in vitro. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11. doi:10.3389/fphar.2020.01065

134. Sun B, Zhang R, Liang Z, et al. Hyperoside attenuates non-alcoholic fatty liver disease through targeting Nr4A1 in macrophages. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;94:107438. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107438

135. Guo X, Zhu C, Liu X, et al. Hyperoside protects against heart failure-induced liver fibrosis in rats. Acta Histochem. 2019;121(7):804–811. doi:10.1016/j.acthis.2019.07.005

136. Han N, Go J-H, Kim H-M, et al. Hyperoside regulates the level of thymic stromal lymphopoietin through intracellular calcium signalling. Phytother Res. 2014;28(7):1077–1081. doi:10.1002/ptr.5099

137. Liu J, Wang Y, Tu Z-C, et al. Bovine β-lactoglobulin covalent modification by flavonoids: effect on the allergenicity and human intestinal microbiota. J Agric Food Chem. 2021;69(24):6820–6828. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.1c02482

138. Ku S, Kim TH, Lee S, et al. Antithrombotic and profibrinolytic activities of isorhamnetin-3-O-galactoside and hyperoside. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;53:197–204. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2012.11.040

139. Song M, Hong M, Lee MY, et al. Selective inhibition of the cytochrome P450 isoform by hyperoside and its potent inhibition of CYP2D6. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;59:549–553. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2013.06.055

140. Zhu W, Xu Y-F, Feng Y, et al. Prophylactic effects of quercetin and hyperoside in a calcium oxalate stone forming rat model. Urolithiasis. 2014;42(6):519–526. doi:10.1007/s00240-014-0695-7

141. Sohn E, Kim J, Kim C-S, et al. Osteomeles schwerinae extract prevents diabetes-induced renal injury in spontaneously diabetic torii rats. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2018;2018:1–8. doi:10.1155/2018/6824215

142. Liu B, Tu Y, He W, et al. Hyperoside attenuates renal aging and injury induced by D-galactose via inhibiting AMPK-ULK1 signaling-mediated autophagy. Aging (Albany NY). 2018;10(12):4197–4212. doi:10.18632/aging.101723

143. Lee D, Shrestha S, Seo WD, et al. Structural and quantitative analysis of antioxidant and low-density lipoprotein-antioxidant flavonoids from the grains of sugary rice. J Med Food. 2012;15(4):399–405. doi:10.1089/jmf.2011.1905

144. Liaudanskas M, Viškelis P, Raudonis R, et al. Phenolic composition and antioxidant activity of Malus domestica leaves. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:10. doi:10.1155/2014/306217

145. Wu Y, Zheng L-J, Wu J-G, et al. Antioxidant activities of extract and fractions from receptaculum nelumbinis and related flavonol glycosides. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13(6):7163–7173. doi:10.3390/ijms13067163

146. Yao X, Zhang D-Y, Luo M, et al. Negative pressure cavitation-microwave assisted preparation of extract of Pyrola incarnata Fisch. rich in hyperin, 2′-O-galloylhyperin and chimaphilin and evaluation of its antioxidant activity. Food Chem. 2015;169:270–276. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.07.115

147. Azzouzi HE, Leptidis S, Doevendans PA, et al. HypoxamiRs: regulators of cardiac hypoxia and energy metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2015;26(9):502–508. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2015.06.008

148. Bećarević M. TNF-alpha and annexin A2: inflammation in thrombotic primary antiphospholipid syndrome. Rheumatol Int. 2016;36(12):1649–1656. doi:10.1007/s00296-016-3569-1

149. Li Q, Xie J, Wang B, et al. Overexpression of microRNA-99a attenuates cardiac hypertrophy. PLoS One. 2016;11:e148480. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0148480

150. Boukes GJ, van de Venter M. The apoptotic and autophagic properties of two natural occurring prodrugs, hyperoside and hypoxoside, against pancreatic cancer cell lines. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016;83:617–626. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2016.07.029

151. Verma N, Singh AP, Gupta A, et al. Antidiarrheal potential of standardized extract of rhododendron arboreum smith flowers in experimental animals. India J Pharmacol. 2011;43:689–693.

152. Li S, Zhang Z, Cain A, et al. Antifungal activity of camptothecin, trifolin, and hyperoside isolated from camptotheca acuminata. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53(1):32–37. doi:10.1021/jf0484780