Back to Journals » Journal of Pain Research » Volume 16

Polypharmacy and Excessive Polypharmacy Among Persons Living with Chronic Pain: A Cross-Sectional Study on the Prevalence and Associated Factors

Authors Zahlan G, De Clifford-Faugère G , Nguena Nguefack HL , Guénette L , Pagé MG , Blais L, Lacasse A

Received 21 March 2023

Accepted for publication 27 August 2023

Published 12 September 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 3085—3100

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S411451

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Timothy Atkinson

Ghita Zahlan,1 Gwenaelle De Clifford-Faugère,1 Hermine Lore Nguena Nguefack,1 Line Guénette,2,3 M Gabrielle Pagé,4,5 Lucie Blais,6 Anaïs Lacasse1

1Département des sciences de la santé, Université du Québec en Abitibi-Témiscamingue, Rouyn-Noranda, Quebec, Canada; 2Faculté de pharmacie, Université Laval, Quebec, Quebec, Canada; 3Centre de recherche, CHU de Québec - Université Laval, Quebec, Quebec, Canada; 4Centre de recherche, Centre hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal (CRCHUM), Montreal, Quebec, Canada; 5Département d’anesthésiologie et de médecine de la douleur, Faculté de médecine, Université de Montréal, Montreal, Quebec, Canada; 6Faculté de pharmacie, Université de Montréal, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

Correspondence: Anaïs Lacasse, Département des sciences de la santé, Université du Québec en Abitibi-Témiscamingue, 445, boul. de l’Université, Rouyn-Noranda, Qc, J9X 5E4, Canada, Tel +1 819 762-0971, 2722, Email [email protected]

Purpose: Polypharmacy can be defined as the concomitant use of ≥ 5 medications and excessive polypharmacy, as the use of ≥ 10 medications. Objectives were to (1) assess the prevalence of polypharmacy and excessive polypharmacy among persons living with chronic pain, and (2) identify sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with excessive polypharmacy.

Patients and Methods: This cross-sectional study used data from 1342 persons from the ChrOnic Pain trEatment (COPE) Cohort (Quebec, Canada). The self-reported number of medications currently used by participants (regardless of whether they were prescribed or taken over-the-counter, or were used for treating pain or other health issues) was categorized to assess polypharmacy and excessive polypharmacy.

Results: Participants reported using an average of 6 medications (median: 5). The prevalence of polypharmacy was 71.4% (95% CI: 69.0– 73.8) and excessive polypharmacy was 25.9% (95% CI: 23.6– 28.3). No significant differences were found across gender identity groups. Multivariable logistic regression revealed that factors associated with greater chances of reporting excessive polypharmacy (vs < 10 medications) included being born in Canada, using prescribed pain medications, and reporting greater pain intensity (0– 10) or pain relief from currently used pain treatments (0– 100%). Factors associated with lower chances of excessive polypharmacy were using physical and psychological pain treatments, reporting better general health/physical functioning, considering pain to be terrible/feeling like it will never get better, and being employed.

Conclusion: Polypharmacy is the rule rather than the exception among persons living with chronic pain. Close monitoring and evaluation of the different medications used are important for all persons, especially those with limited access to care.

Keywords: chronic pain, polypharmacy, excessive polypharmacy, prevalence, associated factors, determinants

Introduction

Defined as pain that persists or recurs for more than three months,1 chronic pain affects approximately 20% of the general population.2 This condition has significant impacts on the physical functioning, emotional well-being, and quality of life of those who live with it. In addition, chronic pain represents a significant economic burden on the people living with the condition, the healthcare system and the society, with an estimated cost in Canada of $40.4 billion per year.3,4

Although various physical and psychosocial approaches are recommended for chronic pain management (eg, exercise, meditation, psychotherapy),5 medications remain used by most people living with this condition (62–84%).6–8 Polypharmacy, which is the simultaneous use of several medications9,10 is common among persons living with chronic pain. Indeed, the pharmacological treatment of this condition is characterized by a combination of various analgesics and co-analgesics (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, opioids, antidepressants, anticonvulsants, muscle relaxants, topical anesthetics, cannabinoids, etc.),11,12 in addition to medications for the treatment of other medical conditions.13,14 Analgesics are the second most commonly used drug class in polymedicated persons.15 Also, painful symptoms have been identified as a determinant of polypharmacy.16–18 Several definitions of polypharmacy have been proposed, such as those focusing on at-risk situations (eg, excessive use of medications; using more medications than clinically indicated; using too many inappropriate medications)19 or numerical categorization (eg, ≥2, 3, 4 or 5 medications).9 The most common definition is the concomitant use of ≥5 medications (all indications combined).20 Excessive polypharmacy, on the other hand, is defined as the concomitant use of ≥10 medications.20

Polypharmacy may be necessary for treating persons with multimorbidity, such as the elderly or people living with chronic pain.21,22 Such “rational” polypharmacy,9 can lead to positive clinical outcomes by approaching diseases through multiple mechanisms of action.23 Still, it can also lead to potential problems, such as an increased risk of drug-related adverse events, drug interactions,24,25 and drug cascades (ie, when one drug is prescribed to treat the adverse effect of another drug, and the adverse effect has been interpreted as a new problem or disease).26 To name only these examples, drug–drug interactions can occur when over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are combined with aspirin, antidepressants and other commonly used medications.27 In addition to being associated with overdoses and deaths, opioids can interact with various CYP2D6 substrates and inhibitors drugs (eg, various antidepressants and antipsychotics often used by persons living with chronic pain) possibly leading to reduced analgesic effects, side effects, prescribing cascaded, withdrawal, and abuse.28 Opioids can also interact with benzodiazepines.29 In terms of health outcomes in the general population, polypharmacy has been shown to be associated with higher symptom burden, poor quality of life,30 presence of depression,31 dementia,32 and mortality.33

Prevalence estimates of polypharmacy in adults living with chronic pain range from 19% to 89% across available studies.18,23,34–37 However, some of them failed to use accepted definitions of polypharmacy and definitions of polypharmacy vary widely between studies. Furthermore, some studied specific populations (eg, people ≥65 years of age or with specific chronic pain conditions such as chronic headaches)18,23 and many studies investigated populations that do not necessarily reflect the reality of people living with chronic pain in the community (eg, populations in tertiary care, hospitalized people with comorbidities, or people receiving home care). Only one study among persons living with chronic pain was conducted in Canada (only among seniors).18 In addition, few studies have measured sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with polypharmacy among people living with chronic pain using multivariable approaches controlling for confounding (factors identified included age, ethnicity, and education level).23

To fill those knowledge gaps, the objectives of the present study were to (1) measure the prevalence of polypharmacy (the use of ≥5 medications) and excessive polypharmacy (≥10 medications) in a community sample of persons living with chronic pain, and (2) identify sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with excessive polypharmacy (vs <10 medications) in this population. For our second objective, we chose to identify factors associated with excessive polypharmacy instead of “regular” polypharmacy as almost all participants of our cohort reported ≥5 medications and as we found more relevant to depict the portrait (and potentially modifiable factors) of participants experiencing riskier pharmacotherapy.

Methods

Study Design and Data Source

The present study used data from the ChrOnic Pain trEatment (COPE) Cohort,38 a research infrastructure resulting from the online recruitment of 1935 persons living with chronic pain. The COPE Cohort aims at better understanding the real-world use of pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments among people living with chronic pain in the province of Quebec, Canada.38 Data were collected between June and October 2019. To be eligible, participants had to report having chronic pain (defined as persistent or recurrent pain for more than three months), be 18 years of age or older, reside in Quebec, and be able to complete an online questionnaire in French. The internet-based recruitment strategy (newsletters, emails, and Facebook® pain support groups) is described elsewhere.38 COPE Cohort participants were previously found to be comparable to random samples of Canadians living with chronic pain regarding age, employment, education, and pain characteristics. Women are, however, overrepresented (84% vs 55–65% in Canadian chronic pain random samples),38 justifying gender-stratified or gender-standardized statistics and multivariable analyses. The study protocol was approved by the research ethics committee of the University of Quebec in Abitibi-Témiscamingue and participants gave their informed electronic consent. The present study used self-reported data from participants who answered the questionnaire section about currently used medications (n = 1342).

Questionnaire and Variables

Participants were invited to complete a web-based questionnaire that included items used in previous research as well as validated composite scales. Items were inspired by the outcome domains and core measures recommended by the Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Assessment of Pain in Clinical Trials (IMMPACT),39,40 the Canadian Minimum Data Set for Research on Chronic Low Back Pain,41 as well as measures included in the Quebec Pain Registry.42 In addition to the variables prioritized by the research team (the balance between validity and parsimony was thoroughly assessed), all indicators identified as a minimum dataset by the Canadian Registry Working Group of the Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research Chronic Pain Network (SPOR CPN)43 were included in the questionnaire: pain location, circumstances surrounding onset, duration, frequency, intensity, neuropathic component, interference, physical function, anxiety and depressive symptoms, age, gender, and occupational status.

Polypharmacy and Excessive polypharmacy. The number of medications currently used was reported by participants. The exact list of medications used was not available. Specifically, participants were asked: “How many different medications do you currently use (whether prescribed or over-the-counter; whether they are for pain or any other health problem)?” This number was measured using a pull-down menu and was recategorized into polypharmacy (≥5 medications) and excessive polypharmacy (≥10 medications) according to the most common definitions found in the literature9,15,44 Self-reported medications currently used by persons with chronic pain have been found accurate.45

Factors associated with excessive polypharmacy and covariables. The diversity of variables in the COPE Cohort allowed for a comprehensive selection of sociodemographic and clinical factors. The choice of relevant variables was inspired by two models. First, the Andersen model46 was considered, which is widely used in studies of health care and drug utilization studies.47,48 It emphasizes on factors influencing health care utilization such as predisposing factors (eg, gender, age, education level, lifestyle), facilitating/inhibiting factors (eg, region of residence, having a family physician), and need factors (eg, self-reported symptoms, perceived general health). Secondly, the choice of variables was inspired by the biopsychosocial model of chronic pain,49 which underlies that biological, psychological, and social factors interact with the nervous system and impact the onset and experience of pain. Thus, the following sociodemographic and clinical variables were included in the present study: (1) Sociodemographic characteristics: Age, gender identity, gender roles according to the Bem Sex-Roles Inventory (BSRI) (feminine, masculine, androgynous, undifferentiated),50,51 country of birth (Canada vs other), occupational status, education level, and living in a remote area (yes/no); (2) Chronic pain characteristics: Generalized pain (yes/no), pain location(s) (eg, back, neck, shoulders, legs, hips; multisite pain was defined as two or more locations, including generalized pain), pain duration, pain intensity in the past seven days (0–10 numerical rating scale), neuropathic component according to the DN4 (yes/no),52 pain interference according to the Brief Pain Inventory,53 and agreeing with the statement “I feel that my pain is terrible and it’s never going to get any better” (this single item from the Pain Catastrophizing Scale54 is referred to as “catastrophizing” in the NIH Minimal Dataset for Chronic Low Back Pain55 and in the STarT Back Screening Tool);56 (3) Pain management indicators: Use of over-the-counter or prescription chronic pain medications or non-pharmacological treatments (yes/no), pain relief reported by participants in regard of their various currently used pain treatments (continuous 0–100% variable), and access to a trusted health professional for pain management (yes/no); (4) Health profile and lifestyle variables: psychological distress (Patient Health Questionnaire-4),57 perceived general health (12-Item Short Form Survey v2 subscale),58 physical functioning (12-Item Short Form Survey v2 subscale),58 feeling the need to reduce alcohol or drug consumption (yes/no), and cigarette smoking (never, past smoking, current smoking). This last set of variables was deemed to reflect the participants comorbidity profile.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to report the characteristics of our sample and to establish the prevalence of polypharmacy and excessive polypharmacy (numbers and proportions for categorical variables; means, standard deviations, medians and interquartile ranges for continuous variables). The prevalence of polypharmacy and excessive polypharmacy were compared across gender identity subgroups (female, male, and non-binary) and age subgroups, and bivariate comparisons (chi-square tests) were conducted to detect statistically significant differences (p < 0.05). As women are overrepresented in the COPE Cohort38 and sex/gender-differences have been found in terms of polypharmacy prevalence,10 gender identity-adjusted prevalence estimates were also computed using a random sample of Canadians living with chronic pain as the standard population.59

To answer the second objective (ie, “what are the sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with excessive polypharmacy?”), a multivariable logistic regression model was conducted. All the above-mentioned covariables were included in the multivariable regression model. The a priori selection of variables to include in our model follows the latest recommendation in that regard;60 this method was favoured over criticized selection techniques such as relying on bivariate regression analysis p-values60 or stepwise selection.61 Although including more variables requires larger sample sizes to achieve statistical power, our substantial sample allowed us this avenue. The fit of the model was analyzed using the Hosmer–Lemeshow test.62 Also, variance inflation factors (VIFs) below 5 were used to detect potential multicollinearity issues.63 The adjusted odd ratios (aORs) estimating the associations between independent variables and the likelihood of using ≥10 medications (vs <10), along with their 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) and p-values, were computed. A sensitivity analysis was performed to assess the impact of using the Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) for selecting independent variables to be included in the multivariable model (prevents overfitting that can be caused by including too many variables in the model). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics for Windows version 27 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

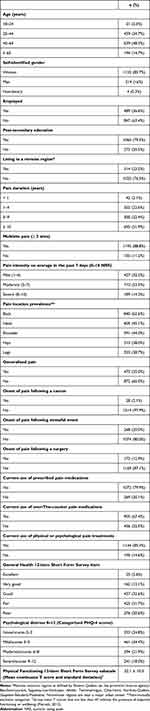

A total of 1342 participants out of 1935 in the COPE Cohort (69.3%) completed the questionnaire section about the number of prescriptions or over-the-counter medications used. No clinically important differences were observed between those included and excluded (n = 593) in terms of mean pain intensity, pain interference score, pain duration, or neuropathic pain screening (p > 0.05). Table 1 presents the characteristics of the sample. Many were between 45 and 64 years of age (48.3%) and 83.7% self-identified as women. Four persons self-identified as non-binary. The majority had post-secondary education (79.5%) and were not employed (63.4%). Multisite pain was very common (88.8%); the most common pain location was the back (62.6%). More than half of the participants reported pain duration of at least ten years (51.9%).

|

Table 1 Characteristics of Participants (n = 1342) |

On average, participants reported using six prescriptions or over-the-counter medications simultaneously (mean ± standard deviation: 6.4 ± 4.5; median: 5; interquartile range: 3–9). The prevalence of polypharmacy (≥5 medications) was 71.4% and excessive polypharmacy (≥10 medications) was 26% (Figure 1). When standardization was applied (gender identity-adjusted prevalence), those values remained similar (71.6% and 27%). Figures 2 and 3 present the prevalence of polypharmacy and excessive polypharmacy across age and gender identity subgroups (non-standardized prevalence). Both types of polypharmacy measures increased with age (p < 0.01). As for gender identity, 71.2% of women and 72.4% of men reported using five or more medications (p > 0.05). In addition, 31.3% of men reported excessive polypharmacy, which was found to be a slightly higher proportion than in women (25.0%), but this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.149) (Figure 3).

|

Figure 1 Prevalence of polypharmacy and excessive polypharmacy (n=1342). Note: Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. |

|

Figure 2 Prevalence of polypharmacy and excessive polypharmacy by age groups. Note: Chi-square tests comparing polypharmacy and excessive polypharmacy across age groups were significant (p < 0.001). |

Table 2 shows the estimates of the multivariable model conducted to study the associations between sociodemographic and clinical factors and excessive polypharmacy among people living with chronic pain. The Hosmer–Lemeshow test confirmed a well-fitted model (Chi-square: 11.9; p = 0.155). The factors associated with an increased likelihood of being in the excessive polypharmacy group were as follows: (1) being Canadian-born (aOR = 4.43, 95% CI: 1.38–14.21), (2) using prescribed pain medications (aOR = 4.44, 95% CI: 2.36–8.35), (3) reporting more severe pain intensity (aOR = 2.43, 95% CI: 1.33–4.41; ie, a clinically meaningful 2-point increase in this continuous variable leads to a 4.86 fold increase in the odds), and (4) reporting greater pain relief in regard of various currently used pain treatments (0–100%) (aOR = 1.01, 95% CI: 1.0–1.01; ie, a clinically meaningful 20% increase in this continuous variable leads to a 2.02 fold increase in the odds). Conversely, the factors associated with a decreased likelihood of reporting excessive polypharmacy were as follows: (1) using physical and psychological pain treatments (aOR = 0.58, 95% CI: 0.36–0.92), (2) reporting better general health (aOR = 0.95, 95% CI: 0.93–0.97), (3) reporting better physical functioning (aOR = 0.95, 95% CI: 0.93–0.96), (4) considering pain to be terrible and feeling like it will never get better (aOR = 0.64, 95% CI: 0.43–0.94), and (5) being employed (aOR = 0.57, 95% CI: 0.39–0.83).

|

Table 2 Results of the Multivariable Analysis Aiming at the Identification of Factors Associated with Excessive Polypharmacy |

The use of LASSO did not change the direction or the statistical significance of the association between polypharmacy and country of birth, use of prescribed pain medications, pain intensity, pain relief, general health, physical functioning, and employment. However, it allowed capturing an association which was of borderline statistical significance in the first model, ie, an association between reporting having access to a trusted health professional for pain management and an increased likelihood of being in the excessive polypharmacy group (aOR = 1.66, 95% CI: 1.10–2.45).

Discussion

The present study evaluated the prevalence of polypharmacy and excessive polypharmacy among a large sample of people living with chronic pain in Quebec, Canada. Polypharmacy was frequent (7 out of 10), and excessive polypharmacy, an even riskier situation, involved 1 in 5 participants. No Canadian study had yet characterized the situation in the general population of adults living with chronic pain. This kind of data is important to convince policymakers, catalyze investments and policy changes, and direct stakeholders towards the situation to motivate them to think about solutions. For example, our results underline the importance of periodic medication review, ie, structured evaluation of a patient’s medicines with the aim of optimizing medicines use and improving health outcomes; entails detecting drug-related problems and recommending interventions.64

Treating chronic pain can require combining chronic pain several drugs that act through different mechanisms.22 Persons living with chronic pain often consult several specialists in search of a cure, receiving a combination of drugs for chronic pain. In addition, they may have other comorbidities, which makes them vulnerable to polypharmacy.11,12 Given the side effects of taking several medications simultaneously and the complications that may arise, the present study also sought to evaluate the sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with excessive polypharmacy.

The present results suggest a prevalence of polypharmacy of 71.4% and, in its severe form, excessive polypharmacy, of 26%. Prevalence estimates vary widely in the literature, ie, frequency of polypharmacy among people living with chronic pain range from 19% to 89% and from 5% to 49% for excessive polypharmacy.18,22,23,30–33 Variations can probably be explained by the country where the study was conducted (eg, healthcare system, cultural differences), the characteristics of the population studied (age, type of pain, community-based vs tertiary care recruitment), the definition of polypharmacy used (≥5 vs other cut-offs), as well as the type of medications considered (prescribed vs over-the-counter). A noteworthy element is that the prevalence of polypharmacy found in our all-age sample of persons living with chronic pain (71% in 2019) is significantly higher than what is found in Quebec adults seen in primary care (32% in 2011)61 and even comparable to what would be found in Quebec seniors (73% in 2016).62

Few studies have investigated factors associated with excessive polypharmacy in people living with chronic pain using multivariable approach23 (none in Canada). Age was found to be positively associated with polypharmacy and excessive polypharmacy. In the literature, several studies have shown that the number of medications taken by members of the general population63,64 increases with age and that age is one of the most common risk factors for excessive polypharmacy. Polypharmacy and excessive polypharmacy have been shown to primarily affect those aged 65 and older.31 However, although the prevalence of polypharmacy and excessive polypharmacy increases with age, it nonetheless affects the younger age groups. Specifically, in the present sample, the ≥65 age group (n = 194) showed a prevalence of polypharmacy and excessive polypharmacy of 79% and 34%, respectively. The 18 to 24-year-old age group (n = 31) had a 65% prevalence of polypharmacy and a 16.1% prevalence of excessive polypharmacy. Although the size of this age group was limited, our results still highlight the importance of closely monitoring and evaluating the medications used in people living with chronic pain, regardless of their age (while keeping in mind that the risks do increase with age).

Previous studies in the general population have reported that women generally take more medications than men and that women show a higher prevalence of polypharmacy.64–66 However, such a difference was not statistically significant in the present study. Although our sample overrepresented women (84% vs 55–65% in Canadian chronic pain random samples;34 probably explained by the web-based recruitment method since women are known to use social media more often and to work more in front of a computer),67,68 gender identity-adjusted prevalence were not different than crude ones and our sample still allowed to make a precise estimation among men (n = 214, narrow confidence intervals).

The present study further sought to identify factors associated with excessive polypharmacy in people living with chronic pain. Keeping in mind that cross-sectional studies are susceptible to reverse causality, the result of the multivariable logistic regression suggested that higher pain intensity, using prescribed pain medications, more severe health status (general health and physical functioning), and having access to a trusted healthcare professional were associated with a higher risk of excessive polypharmacy. These results are in line with our expectations as more medications are often prescribed to persons with more severe pain and comorbidities. As expected, participants using non-pharmacological approaches (physical and psychological treatments) were less likely to report excessive polypharmacy, underlying the place and importance of a multimodal approach (physical and psychological approaches in addition to medication).69 Persons with access to healthcare also have more prescription opportunities. Independently from pain severity and the use of non-pharmacological approaches, participants reporting greater pain relief on a 0% to 100% scale were more likely to experience excessive polypharmacy. Although this result needs to be investigated further, it allows us to note that the use of more than 10 medications, although riskier, may be “rational” polypharmacy and lead to positive clinical outcomes in some cases (harnessing the combination of different analgesics and co-analgesics that act through various mechanisms, in addition to multimorbidity management). In a context where opioids prescribing is highly controversial and where patients often experience forced withdrawal and inadequate pain relief,70 rational polypharmacy offers an alternative approach by combining non-opioid medications and address the multidimensional nature of chronic pain while minimizing opioid-related risks. Implementing rational polypharmacy necessitates careful assessment, individualized treatment plans, and close monitoring to achieve optimal pain relief while mitigating unintended consequences.

Regarding the country of origin, an unexpected result was that participants born in Canada were more likely to experience excessive polypharmacy. Various ad hoc bivariate comparisons in our database suggest that this result is not explained by greater access to private drug insurance and different access to medication (N.B. private and public prescription drug insurance are the two only options in the province of Quebec as insurance is mandatory). This result can possibly be explained by the variability in the use of drugs between countries71,72 or the tendency to turn to traditional approaches,73,74 which can also vary from one country to another. Explanations could be further explored in a qualitative study focused on persons living with chronic pain’s experience.

In the present study, participants were invited to report if they considered pain terrible and felt like it will never get better. This single-item question used in our study is referred to as “catastrophizing” in the NIH Minimal Dataset for Chronic Low Back Pain51 and in the STarT Back Screening Tool,52 although it only covers one aspect of the well-validated and commonly used 13-item Pain Catastrophizing Scale.50 In the literature, high pain catastrophizing has been found to predict analgesic use.75–77 However, the participants in the present study who considered their pain to be terrible and who felt that it will never get better (high catastrophizing profile) were not found to experience more excessive polypharmacy. As this result departs from previous research and that variable was only retained in our main regression model (not with LASSO; probably as it is correlated with another variable), future investigations appear necessary.

Also, in our study, it was found that reporting being employed was associated with a decreased likelihood of reporting excessive polypharmacy. Our results are at odds with the literature, in which polypharmacy is not associated with employment among non-pain populations.78–80 As the analysis was adjusted for pain intensity (we could have argued that people less affected by pain are more likely to work), this association merits more attention in further studies.

Recommendations

Our results underline the importance of close monitoring and regular medication reviews in this population. However, because many persons with chronic pain do not have access to regular follow-ups by physicians, this can be challenging and underlines the importance of the involvement of other healthcare professionals such as pharmacists and nurse practitioners. People living with chronic pain could be targeted with personalized front-line interventions (eg, targeting people with poorer general health) and asked about the medications they are taking at each medical visit. Also, there is a need for persons with chronic pain to be better informed about risks and benefits of polypharmacy as well as the resources at their disposal in the event of questions or the need for an intervention. We suggest that community pharmacists should be put to good use for instance by being easily accessible healthcare professionals for following persons living with chronic pain and for optimizing their pharmacotherapy. Future longitudinal studies that take into account the specific types of medications a person is using in order to assess if polypharmacy is rational or irrational are necessary. Also, further studies are needed to better describe interventions aimed at optimizing the use of medications among people living with chronic pain.

Strength and Limitations

Several strengths deserve to be mentioned. First, the study design allowed us to recruit a large sample without geographic barriers, and COPE participants have been previously found to be comparable to random samples of Canadians living with chronic pain in terms of age, employment, education level, and pain characteristics. Although women are overrepresented in the Cohort, the comparison of crude and gender identity-adjusted prevalence estimates revealed no bias. Second, our sample was drawn from the community (not just healthcare users/patients). Third, our study used accepted definitions of polypharmacy and most variables were measured using validated and recognized measurement instruments. Fourth, a multivariable approach was used to investigate the associations between many factors that were never studied before, not to mention the application of sensitivity analyses. The main limitation of this study is that the detailed list of medications used by participants was not available for analysis and our polypharmacy measure relied on the self-reported number of medications used (eg, risk of underestimation or overestimation; not sure if participants included natural health products and multivitamins). Other limitations need to be considered when interpreting the study results. Indeed, the advertisements for the recruitment of participants as well as the questionnaire were only available in French. In addition, all data were self-reported which opens to memory bias, socially desirable responses, and under-reporting (eg, under-reporting of pain medication use by not considering adjuvant drugs). Also, the cross-sectional design limits the assessment of causal relationships. Although, validated measures of psychological distress, general health, and physical functioning were used, they remain proxies for exact comorbidities (not measured in the questionnaire).

Conclusion

Polypharmacy is very high in persons living with chronic pain (7 out of 10). Excessive polypharmacy, an even riskier situation, affects 1 in 5 people. Our results underline the importance of close monitoring and regular medication reviews in this population. We hope that our results will serve as an argument towards justification of resources for greater awareness among persons living with chronic pain and clinicians.

Abbreviations

CP, Chronic pain; US, United States; COPE, ChrOnic Pain trEatment; IMMPACT, Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Assessment of Pain in Clinical Trials; SPOR CPN, Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research Chronic Pain Network; BSRI, Bem Sex Role Inventory; BPI, Brief Pain Inventory; DN4, Douleur Neuropathique 4; NRS, Numeric rating scale; PHQ-4, 4-item Patient Health Questionnaire; SF-12, 12-Item Short Form Survey.

Data Sharing Statement

The Cope Cohort dataset is not readily available because participants did not initially provide consent to open data. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and conditionally to a proper ethical approval for a secondary data analysis. Programming codes can be obtained directly from the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

Ethical approval was provided by the Université du Québec in Abitibi-Témiscamingue’s research ethics committee (#2018-05-Lacasse, A.). All participants provided free and informed consent. Our study complies with the Tri-Council Policy Statement and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the study participants for their contribution to the research, and Ms. Véronique Gagnon, who was involved in the implementation, data cleaning and data management of the COPE Cohort. Special thanks to Ms. Geneviève Lavigne who provided assistance for scientific writing and English language editing.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

The implementation of the COPE Cohort was supported by the Quebec Network on Drug Research and the exploitation of its data was co-funded by the Quebec Pain Research Network, two thematic networks of the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé (FRQS).

Disclosure

In part of her Masters’ degree training, GZ (first author) received scholarships from the Fondation de l’Université du Québec en Abitibi-Témiscamingue (FUQAT) in partnership with the Pharmacie Jean-Coutu de Rouyn-Noranda (community pharmacy) and travel awards from the Quebec Pain Research Network (QPRN). At the time the study was conducted, AL held a Junior 2 research scholarship from the FRQS in partnership with the Quebec SUPPORT Unit (Support for People and Patient-Oriented Research and Trials) and MGP a Junior 1 research scholarship from the FRQS. The Chronic Pain Epidemiology Laboratory led by AL is funded by the FUQAT, in partnership with local businesses: the Pharmacie Jean-Coutu de Rouyn-Noranda and Glencore Fonderie Horne (copper smelter). LB received research grants from AstraZeneca, TEVA and Genentech, as well as consultation fees from AstraZeneca, TEVA and Genentech for projects unrelated to this study. MGP received honoraria from Canopy Growth and research funds from Pfizer Canada for projects unrelated to this study. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Treede RD, Rief W, Barke A, et al. Chronic pain as a symptom or a disease: the IASP classification of Chronic Pain for the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). Review. Pain. 2019;160(1):19–27. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001384

2. Andrew R, Derry S, Taylor RS, Straube S, Phillips CJ. The costs and consequences of adequately managed chronic non-cancer pain and chronic neuropathic pain. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t. Review. Pain Pract. 2014;14(1):79–94. doi:10.1111/papr.12050

3. Campbell Fiona MH, Choinière M, El-Gabalawy H, et al. Working together to better understand, prevent, and manage chronic pain: what we heard. Ottawa: Report by the Canadian Pain Task Force – Health Canada; 2020.

4. Chauvin M. Vivre avec une douleur chronique, c’est se battre pour garder l’espoir [Living with chronic pain means fighting to remain positive]. Soins la revue de reference infirmiere. 2017;62(815):34–35. French. doi:10.1016/j.soin.2017.03.022

5. Campbell Fiona MH, Choinière M, El-Gabalawy H, Laliberté J, Sangster M, Swidrovich J. Chronic pain in Canada: laying a foundation for action. Ottawa: Report by the Canadian Pain Task Force – Health Canada; 2019.

6. Andersson HI, Ejlertsson G, Leden I, Schersten B. Impact of chronic pain on health care seeking, self care, and medication. Results from a population-based Swedish study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53(8):503–509. doi:10.1136/jech.53.8.503

7. Toblin RL, Mack KA, Perveen G, Paulozzi LJ. A population-based survey of chronic pain and its treatment with prescription drugs. Pain. 2011;152(6):1249–1255. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2010.12.036

8. Choinière M, Dion D, Peng P, et al. The Canadian STOP-PAIN project–Part 1: who are the patients on the waitlists of multidisciplinary pain treatment facilities? Can J Anesth. 2010;57(6):539–548. doi:10.1007/s12630-010-9305-5

9. Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalisch-Ellett L, Caughey GE. What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):230. doi:10.1186/s12877-017-0621-2

10. Guillot J, Maumus-Robert S, Bezin J. Polypharmacy: a general review of definitions, descriptions and determinants. Therapies. 2020;75(5):407–416. doi:10.1016/j.therap.2019.10.001

11. Libert F, Adam F, Eschalier A, Brasseur L. Les médicaments adjuvants (ou co-analgésiques). Douleur Et Analgésie. 2006;19(4):91–97. doi:10.1007/s11724-006-0026-z

12. Oertel BG, Lotsch J. Clinical pharmacology of analgesics assessed with human experimental pain models: bridging basic and clinical research. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;168(3):534–553. doi:10.1111/bph.12023

13. Ferguson M, Svendrovski A, Katz J. Association between multimorbid disease patterns and pain outcomes among a complex chronic care population in Canada. J Pain Res. 2020;13:3045–3057. doi:10.2147/jpr.S269648

14. Scherer M, Hansen H, Gensichen J, et al. Association between multimorbidity patterns and chronic pain in elderly primary care patients: a cross-sectional observational study. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17(1):68. doi:10.1186/s12875-016-0468-1

15. Hovstadius B, Astrand B, Petersson G. Dispensed drugs and multiple medications in the Swedish population: an individual-based register study. BMC Clin Pharmacol. 2009;9(1):11. doi:10.1186/1472-6904-9-11

16. Jyrkka J, Enlund H, Korhonen MJ, Sulkava R, Hartikainen S. Patterns of drug use and factors associated with polypharmacy and excessive polypharmacy in elderly persons: results of the Kuopio 75+ study: a cross-sectional analysis. Drugs Aging. 2009;26(6):493–503. doi:10.2165/00002512-200926060-00006

17. Onder G, Liperoti R, Fialova D, et al. Polypharmacy in nursing home in Europe: results from the SHELTER study. J Gerontol a Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67(6):698–704. doi:10.1093/gerona/glr233

18. Ramage-Morin PL. Medication use among senior Canadians. Health Rep. 2009;20(1):37–44.

19. WHO Centre for Health Development. A Glossary of Terms for Community Health Care and Services for Older Persons. Kobe, Japan: WHO Centre for Health Development; 2004.

20. Hovstadius B, Petersson G. Factors leading to excessive polypharmacy. Clin Geriatr Med. 2012;28(2):159–172. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2012.01.001

21. Aggarwal P, Woolford SJ, Patel HP. Multi-morbidity and polypharmacy in older people: challenges and opportunities for clinical practice. Geriatrics. 2020;5(4):85. doi:10.3390/geriatrics5040085

22. Giummarra MJ, Gibson SJ, Allen AR, Pichler AS, Arnold CA. Polypharmacy and chronic pain: harm exposure is not all about the opioids. Pain Med. 2015;16(3):472–479. doi:10.1111/pme.12586

23. Ferrari A, Baraldi C, Licata M, Rustichelli C. Polypharmacy among headache patients: a cross-sectional study. Multicenter Study Observational Study. CNS Drugs. 2018;32(6):567–578. doi:10.1007/s40263-018-0522-8

24. Chang TI, Park H, Kim DW, et al. Polypharmacy, hospitalization, and mortality risk: a nationwide cohort study. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1–9. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-75888-8

25. Shi S, Mörike K, Klotz U. The clinical implications of ageing for rational drug therapy. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;64(2):183–199. doi:10.1007/s00228-007-0422-1

26. Nunnari P, Ceccarelli G, Ladiana N, Notaro P. Prescribing cascades and medications most frequently involved in pain therapy: a review. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021;25(2):1034–1041. doi:10.26355/eurrev_202101_24673

27. Moore N, Pollack C, Butkerait P. Adverse drug reactions and drug-drug interactions with over-The-counter NSAIDs. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2015;11:1061–1075. doi:10.2147/tcrm.S79135

28. Bain KT, Knowlton CH. Role of opioid-involved drug interactions in chronic pain management. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2019;119(12):839–847. doi:10.7556/jaoa.2019.136

29. Jones JD, Mogali S, Comer SD. Polydrug abuse: a review of opioid and benzodiazepine combination use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;125(1–2):8–18. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.07.004

30. Berndt S, Maier C, Schütz HW. Polymedication and medication compliance in patients with chronic non-malignant pain. Pain. 1993;52(3):331–339. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(93)90167-n

31. Schneider J, Algharably EAE, Budnick A, Wenzel A, Dräger D, Kreutz R. High prevalence of multimorbidity and polypharmacy in elderly patients with chronic pain receiving home care are associated with multiple medication-related problems. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:686990. doi:10.3389/fphar.2021.686990

32. Siebenhuener K, Eschmann E, Kienast A, et al. Chronic pain: how challenging are DDIs in the analgesic treatment of inpatients with multiple chronic conditions? PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0168987. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0168987

33. Taylor R, Pergolizzi V, J J, Puenpatom RA, Summers KH. Economic implications of potential drug-drug interactions in chronic pain patients. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;13(6):725–734. doi:10.1586/14737167.2013.851006

34. Lacasse A, Gagnon V, Nguena Nguefack HL, et al. Chronic pain patients’ willingness to share personal identifiers on the web for the linkage of medico-administrative claims and patient-reported data: the chronic pain treatment cohort. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2021;30(8):1012–1026. doi:10.1002/pds.5255

35. Turk DC, Dworkin RH, Allen RR, et al. Core outcome domains for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2003;106(3):337–345. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2003.08.001

36. Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Farrar JT, et al. Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2005;113(1–2):9–19. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.012

37. Lacasse A, Roy JS, Parent AJ, et al. The Canadian minimum dataset for chronic low back pain research: a cross-cultural adaptation of the National Institutes of Health Task Force Research Standards. CMAJ Open. 2017;5(1):E237–E248. doi:10.9778/cmajo.20160117

38. Choinière M, Ware MA, Pagé MG, et al. Development and implementation of a registry of patients attending multidisciplinary pain treatment clinics: the Quebec Pain Registry. Pain Res Manag. 2017;2017:8123812. doi:10.1155/2017/8123812

39. CPN. Chronic pain network annual report 2016/2017, Hamilton; 2017.

40. Van der Heyden J, Berete F, Renard F, et al. Assessing polypharmacy in the older population: comparison of a self‐reported and prescription based method. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2021;30(12):1716–1726. doi:10.1002/pds.5321

41. Lacasse A, Ware MA, Bourgault P, et al. Accuracy of self-reported prescribed analgesic medication use: linkage between the Quebec Pain Registry and the Quebec Administrative Prescription Claims Databases. Clin J Pain. 2016;32(2):95–102. doi:10.1097/AJP.0000000000000248

42. Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(1):1–10. doi:10.2307/2137284

43. Babitsch B, Gohl D, von Lengerke T. Re-revisiting Andersen’s behavioral model of health services use: a systematic review of studies from 1998–2011. Psychosoc Med. 2012;9:Doc11. doi:10.3205/psm000089

44. Gamboa CM, Colantonio LD, Brown TM, Carson AP, Safford MM. Race-sex differences in statin use and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol control among people with diabetes mellitus in the reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke study. Comparative Study Multicenter Study Observational Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(5). doi:10.1161/JAHA.116.004264

45. Gatchel RJ, Peng YB, Peters ML, Fuchs PN, Turk DC. The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: scientific advances and future directions. Psychol Bull. 2007;133(4):581–624. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.581

46. Bem SL. The measurement of psychological androgyny. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1974;42(2):155–162. doi:10.1037/h0036215

47. Fontayne P, Sarrazin P, Famose J-P. The Bem Sex-Role inventory: validation of a short version for French teenagers. Eur Rev Appl Psychol. 2000;50(4):405–416.

48. Bouhassira D, Attal N, Alchaar H, et al. Comparison of pain syndromes associated with nervous or somatic lesions and development of a new neuropathic pain diagnostic questionnaire (DN4). Pain. 2005;114(1–2):29–36. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2004.12.010

49. Cleeland CS. The brief pain inventory user guide; 2009. Available from: https://www.mdanderson.org/content/dam/mdanderson/documents/Departments-and-Divisions/Symptom-Research/BPI_UserGuide.pdf.

50. Sullivan MJ, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995;7(4):524. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.7.4.524

51. Deyo RA, Dworkin SF, Amtmann D, et al. Report of the NIH task force on research standards for chronic low back pain. J Pain. 2014;15(6):569–585. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2014.03.005

52. Bruyere O, Demoulin M, Brereton C, et al. Translation validation of a new back pain screening questionnaire (the STarT Back Screening Tool) in French. Arch Public Health. 2012;70(1):12. doi:10.1186/0778-7367-70-12

53. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Löwe B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(6):613–621. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613

54. Maruish ME. User’s Manual for the SF-12v2 Health Survey.

55. Moulin DE, Clark AJ, Speechley M, Morley-Forster PK. Chronic pain in Canada--prevalence, treatment, impact and the role of opioid analgesia. Pain Res Manag. 2002;7(4):179–184. doi:10.1155/2002/323085

56. Sourial N, Vedel I, Le Berre M, Schuster T. Testing group differences for confounder selection in nonrandomized studies: flawed practice. CMAJ. 2019;191(43):E1189–E1193. doi:10.1503/cmaj.190085

57. Katz MH. Multivariable Analysis: A Practical Guide for Clinicians and Public Health Researchers California.

58. Bursac Z, Gauss CH, Williams DK, Hosmer DW. Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Source Code Biol Med. 2008;3(1):17. doi:10.1186/1751-0473-3-17

59. Vatcheva KP, Lee M, McCormick JB, Rahbar MH. Multicollinearity in regression analyses conducted in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiology. 2016;6(2). 227. doi:10.4172/2161-1165.1000227

60. Huiskes VJ, Burger DM, van den Ende CH, van den Bemt BJ. Effectiveness of medication review: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Fam Pract. 2017;18(1):5. doi:10.1186/s12875-016-0577-x

61. Nguyen TN, Ngangue P, Haggerty J, Bouhali T, Fortin M. Multimorbidity, polypharmacy and primary prevention in community-dwelling adults in Quebec: a cross-sectional study. Fam Pract. 2019;36(6):706–712. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmz023

62. Gosselin ESM, Dubé M, Sirois C. Portrait de la polypharmacie chez les aînés québécois entre 2000 et 2016 [Portrait of polypharmacy among Quebec seniors between 2000 and 2016]. Institut national de santé publique du Québec, Québec; Gouvernement du Québec; 2020.

63. Veehof L, Stewart R, Haaijer-Ruskamp F, Jong BM. The development of polypharmacy. A longitudinal study. Fam Pract. 2000;17(3):261–267. doi:10.1093/fampra/17.3.261

64. Hajjar ER, Cafiero AC, Hanlon JT. Polypharmacy in elderly patients. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2007;5(4):345–351. doi:10.1016/j.amjopharm.2007.12.002

65. Bjerrum L, Sogaard J, Hallas J, Kragstrup J. Polypharmacy: correlations with sex, age and drug regimen. A prescription database study. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;54(3):197–202. doi:10.1007/s002280050445

66. Haider SI, Johnell K, Thorslund M, Fastbom J. Trends in polypharmacy and potential drug-drug interactions across educational groups in elderly patients in Sweden for the period 1992–2002. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;45(12):643–653. doi:10.5414/cpp45643

67. CEFRIO. L’usage des médias sociaux au Québec [The use of social media in Quebec]. Enquête NETendances; 2018.

68. Marshall KJ. Utilisation de l’ordinateur au travail. L’emploi et le Revenu en Perspective [Computer use at work. Employment and Income in Perspective]. Perspective. 2001;2(5):e0115.

69. Bushnell MC, Frangos E, Madian N. Non-pharmacological treatment of pain: grand challenge and future opportunities. Front Pain Res. 2021;2:696783. doi:10.3389/fpain.2021.696783

70. Comerci G Jr, Katzman J, Duhigg D. Controlling the Swing of the Opioid Pendulum. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(8):691–693. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1713159

71. Phill O’Neill JS. International comparison of medicines usage: quantitative analysis, United Kingdom; 2013: 36. Available from: https://www.lif.se/contentassets/a0030c971ca6400e9fbf09a61235263f/international-comparison-of-medicines-usage-quantitative-analysis.pdf.

72. Sarnak DO, Squires D, Kuzmak G, Bishop S. Paying for prescription drugs around the world: why is the US an outlier. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund), 2017; 2017: 1–14. Available from: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/documents/___media_files_publications_issue_brief_2017_oct_sarnak_paying_for_rx_ib_v2.pdf.

73. Burke A, Kuo T, Harvey R, Wang J. An international comparison of attitudes toward traditional and modern medicine in a Chinese and an American Clinic Setting. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2011;2011:204137. doi:10.1093/ecam/nen065

74. Rojas P, Jung-Cook H, Ruiz-Sánchez E, et al. Historical aspects of herbal use and comparison of current regulations of herbal products between Mexico, Canada and the United States of America. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(23):15690. doi:10.3390/ijerph192315690

75. Shiue KY, Dasgupta N, Naumann RB, Nelson AE, Golightly YM. Sociodemographic and clinical predictors of prescription opioid use in a longitudinal community-based cohort study of middle-aged and older adults. J Aging Health. 2022;34(2):213–220. doi:10.1177/08982643211039338

76. Finan PH, Carroll CP, Moscou-Jackson G, et al. Daily opioid use fluctuates as a function of pain, catastrophizing, and affect in patients with sickle cell disease: an electronic daily diary analysis. J Pain. 2018;19(1):46–56. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2017.08.010

77. Jensen MK, Thomsen AB, Højsted J. 10-year follow-up of chronic non-malignant pain patients: opioid use, health related quality of life and health care utilization. Eur J Pain. 2006;10(5):423–433. doi:10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.06.001

78. Haider SI, Johnell K, Thorslund M, Fastbom J. Analysis of the association between polypharmacy and socioeconomic position among elderly aged ≥77 years in Sweden. Clin Ther. 2008;30(2):419–427. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.02.010

79. Downing J, Taylor R, Mountain R, et al. Socioeconomic and health factors related to polypharmacy and medication management: analysis of a Household Health Survey in North West Coast England. BMJ Open. 2022;12(5):e054584. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-054584

80. Assari S, Bazargan M. Race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and polypharmacy among Older Americans. Pharmacy. 2019;7(2):41. doi:10.3390/pharmacy7020041

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.