Back to Journals » Clinical Epidemiology » Volume 8

Pilot study of participant-collected nasal swabs for acute respiratory infections in a low-income, urban population

Authors Vargas C, Wang L, Castellanos de Belliard Y, Morban M, Diaz H, Larson E, LaRussa P, Saiman L, Stockwell M

Received 6 September 2015

Accepted for publication 10 November 2015

Published 6 January 2016 Volume 2016:8 Pages 1—5

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S95847

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Henrik Sørensen

Celibell Y Vargas,1 Liqun Wang,1 Yaritza Castellanos de Belliard,1 Maria Morban,1 Hilbania Diaz,1 Elaine L Larson,2,3 Philip LaRussa,1 Lisa Saiman,1,4 Melissa S Stockwell1,5,6

1Department of Pediatrics, 2School of Nursing, 3Department of Epidemiology, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, 4Department of Infection Prevention and Control, NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital, 5Department of Population and Family Health, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, 6NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital, New York, NY, USA

Objective: To assess the feasibility and validity of unsupervised participant-collected nasal swabs to detect respiratory pathogens in a low-income, urban minority population.

Methods: This project was conducted as part of an ongoing community-based surveillance study in New York City to identify viral etiologies of acute respiratory infection. In January 2014, following sample collection by trained research assistants, participants with acute respiratory infection from 30 households subsequently collected and returned a self-collected/parent-collected nasal swab via mail. Self/parental swabs corresponding with positive reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction primary research samples were analyzed.

Results: Nearly all (96.8%, n=30/31) households agreed to participate; 100% reported returning the sample and 29 were received (median time: 8 days). Most (18; 62.1%) of the primary research samples were positive. For eight influenza-positive research samples, seven (87.5%) self-swabs were also positive. For ten other respiratory pathogen-positive research samples, eight (80.0%) self-swabs were positive. Sensitivity of self-swabs for any respiratory pathogen was 83.3% and 87.5% for influenza, and specificity for both was 100%. There was no relationship between level of education and concordance of results between positive research samples and their matching participant swab.

Conclusion: In this pilot study, self-swabbing was feasible and valid in a low-income, urban minority population.

Keywords: influenza, upper respiratory infection, influenza-like illness, self-swab, community-based

A Letter to the Editor has been received and published for this article.

Introduction

Community-based studies are an important component of surveillance for acute respiratory infections/influenza-like illness (ARI/ILI). Using nasal self-swabbing to obtain samples for laboratory analysis has advantages during outbreaks or pandemics, as this strategy would reduce the time required for health care professionals to obtain specimens, as well as lessen their risk of becoming infected. Furthermore, self-swabbing could be used to identify ARI/ILI etiologies in the community that might be missed from reliance on medically-attended disease surveillance.

Previous self-swab studies for ARI/ILI have demonstrated their feasibility.1–3 However, few have been performed in the USA, and the use of self-swabs in a low-income, minority, urban population has not been assessed. Understanding the feasibility and validity of nasal self-swabs in this population is important. First, it is a population at high risk for infection and transmission due to overcrowding.4,5 Second, being low-income, Latino, publicly insured, foreign born, and having a lower education level are factors associated with lower likelihood of having a primary health care provider and seeking care for illness.6,7 Therefore, the objective of this pilot study was to assess the feasibility and validity of unsupervised self- and/or parental-swabbing for children in a low-income, urban minority population.

Methods

This pilot study was a component of an ongoing 5-year community-based ARI/ILI surveillance study, which includes a cohort of 250 households.7 Participants are from a primarily immigrant Latino population in Northern Manhattan in New York City. Northern Manhattan is one of the most disadvantaged areas in New York City; 43.7% of the population receives federal income support.8 As part of the ongoing study, families answer twice-weekly text messages to report ARI/ILI-associated symptoms among household members. Phone calls are used by research staff to follow-up on positive reports. If ARI/ILI criteria are met, a home visit is scheduled and a nasal swab is obtained from symptomatic participants by the research staff.7

From January 7 to 23, 2014, after the swabs were collected for the primary study by the research staff, each participant was asked to obtain a nasal swab later that day, either from themselves (if they were ≥17 years old) or from their symptomatic child. The Columbia University Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved this study with use of an information sheet and verbal consent. For volunteers, the study team demonstrated how to obtain a nasal swab. Written instructions (English and Spanish) were also provided. Participants were provided with a self-swab kit and a pre-addressed, prestamped mailer that followed the US Postal Service guidelines for biological substances.9 Participants were advised that if the swab was not sent the day it was obtained, it should be stored in the refrigerator. The research staff followed up by telephone the next day to confirm that the self-swab was obtained and sent. Each participant obtaining the self-swab received a round-trip New York City MetroCard (value US$5.00) when the specimen was received.

To assess feasibility, we determined the proportion of households agreeing to perform the self-swab, the proportion returning the swab, and the number of days elapsed between when the participants received the kit and when the swab arrived in the laboratory. All swabs obtained by research staff were analyzed by a commercially available multiplex reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions (BioFire Diagnostics, Inc., Salt Lake City, UT, USA). The assay has a limit of detection (LOD) of 1–200 tissue culture infective dose (TCID)50/mL for influenza, and an LOD of 4–30,000 TCID50/mL for non-influenza viral pathogens, of which only rhinovirus/enterovirus has an LOD of more than 5,000 TCID50/mL. The LOD for bacterial respiratory pathogens ranges from 30 colony forming units (CFU)/mL to 4,000 CFU/mL.10 If the swab obtained for the primary research study was positive for a respiratory pathogen, the self-swab was also analyzed by multiplex reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. The percent of self-swabs positive for the same pathogen as the corresponding swab obtained by research staff was calculated. Chi-square tests were used to assess if there were differences in demographic factors (age, sex, English proficiency, born in the US/elsewhere, and educational level) between those with a positive research swab who also had a positive self-swab versus a negative self-swab. Finally, the sensitivity of the self-swab using the research swab as the gold standard was assessed. All analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics V22.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

We approached 31 households to take part in the pilot study and 30 (96.8%) agreed (28 unique households; two households took part twice). These represented 15 ill adults and 15 ill children (Table 1). All households reported in the follow-up call that they had obtained the sample, and we received 29 samples (96.7%) (most samples [n=28] by mail, and one specimen brought directly to the laboratory). Of those who mailed the specimen, most (78.6%) reported mailing it within 1 day; all reported mailing it within 2 days. The median time between the kit being dropped off and arrival to the laboratory was 8 days (range: 3–99 days).

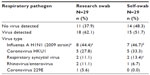

Of the 29 swabs received, 18 (62.1%, from seven adults and eleven children) had a corresponding research swab that was positive for a respiratory pathogen. Seven (87.5%) corresponding self-swabs were concordant with the positive research swabs for influenza, and eight (80.0%) corresponding self-swabs were concordant with the research swab for non-influenza pathogens (Table 2). The kappa statistic between research and self-swab was 0.84. There were no differences in demographic variables, including education level or days between drop-off and receipt of swabs, among participants whose self- and research-staff obtained swabs correlated versus those whose swabs did not correlate (Table 1). Of the self-swab samples that had a corresponding positive research swab, the longest time a self-swab sample took to arrive was 17 days; this swab was positive for respiratory syncytial virus and parainfluenza. The research swab was positive only for respiratory syncytial virus. Overall sensitivity for the self-swab to capture any respiratory pathogen was 83.3% (95% confidence interval [CI] 64%–102%), and 87.5% (95% CI 63%–112%) for influenza cases. Specificity was 100%, and negative and positive predictive values were 78.6% and 100%, respectively. Sensitivity to capture respiratory pathogens for a person taking their own swab was 71.4% (95% CI 32%–111%), and for a parent taking a swab of a child, was 90.9% (95% CI 73%–109%); sensitivity for influenza was 100% for someone taking their own self-swab, and 75.0% (95% CI 63%–112%) for a parent taking the swab.

Discussion

In this pilot study, we demonstrated that the use of self-swabbing for surveillance of respiratory pathogens is feasible and acceptable in a low-income, urban community. Nearly all who were approached agreed to participate and obtained and returned swabs. There was good concordance between nasal swabs obtained by research staff or by the participant.

This study also confirmed that standard US Postal Service mailings can be used to provide viable self-swab specimens. The feasibility of using the postal service is important, since other commercial shipping services may be less accessible to low-income populations due to the limited availability of drop-off locations, the need for someone to be available for home pickup and, furthermore, are more costly.3 Although this study was completed during the winter, which may have reduced sample degradation, a previous study demonstrated the integrity and quality of self-swabs sent via regular mail across seasons.11

While the collection of self-swab samples is useful for the surveillance of ill individuals and collection of samples of nonmedically attended infections, another potential use of self-swabbing in a household is to collect samples from asymptomatic individuals in affected households. Characterizing the level of asymptomatic infection is useful, as these individuals may also be contagious. In studies conducted during the 2009 influenza A H1N1 pandemic, up to 28% of those who were infected were asymptomatic.12–14 However, there are few data available on asymptomatic infection for seasonal influenza and other respiratory pathogens.12–14 Since serial swabbing would likely be needed to monitor the duration of asymptomatic shedding, it may be cost- and time-prohibitive for participants to be swabbed daily at a research site or by a health care worker in the household.

There were limitations to this study. Although there was high compliance with returning the self-swab samples, and all participants reported returning them within 2 days, there was wide variation in arrival time of mailed samples. It is not known whether participants sent samples later than reported, whether the postal service was slow, or whether the sample was delayed in the University’s central mailing office. In addition, this pilot study was conducted concordantly with an ongoing ARI/ILI surveillance study in which participants observed the research assistant perform the nasal swab, which may have improved self-swab technique. In this study, however, the research assistant was not present when the self-swab was taken, and it is both feasible and ideal to first instruct participants of the proper technique in a self-swab study. Further, participants were provided a round-trip New York City MetroCard (value US$5.00) for their time and effort; other populations might be less inclined to participate for this incentive or without an incentive. However, other studies, including those from other countries, have also demonstrated high compliance with self-swabs.15–17 This pilot study took place in a single community and should be repeated with a larger and more diverse population within this geographical area, as well as with populations from other geographical areas. A strength of this study is that there was the direct comparison of self-swab samples with research samples from the same participant.

In conclusion, self-swabbing was acceptable and feasible in a low-income, urban minority population.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Carrie Reed and Lyn Finelli from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The research swabs mentioned in this study were obtained as part of a project supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U01IP000618).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Akmatov MK, Pessler F. Self-collected nasal swabs to detect infection and colonization: a useful tool for population-based epidemiological studies? Int J Infect Dis. 2011;15(9):e589–e593. | |

Dhiman N, Miller RM, Finley JL, et al. Effectiveness of patient-collected swabs for influenza testing. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(6):548–554. | |

Thompson MG, Ferber JR, Odouli R, et al. Results of a pilot study using self-collected mid-turbinate nasal swabs for detection of influenza virus infection among pregnant women. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2015;9(3):155–156. | |

Lofgren E, Fefferman NH, Naumov YN, Gorski J, Naumova EN. Influenza seasonality: underlying causes and modeling theories. J Virol. Jun 2007;81(11):5429–5436. | |

US Department of Housing and Urban Development. Measuring Overcrowding in Housing. Washington DC: US Department of Housing and Urban Development; 2007. Available from: http://www.huduser.org/portal//publications/pdf/Measuring_Overcrowding_in_Hsg.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2015. | |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Monitoring the Nation’s Health. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2014. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_10/sr10_260.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2015. | |

Stockwell MS, Reed C, Vargas CY, et al. MoSAIC: Mobile Surveillance for Acute Respiratory Infections and Influenza-Like Illness in the Community. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;180(12):1196–1201. | |

Department of City Planning of New York, Community Portal [webpage on the Internet]. New York City: NYC Planning; 2014. Available from: http://www.nyc.gov/html/dcp/html/neigh_info/mn12_info.shtml. Accessed May 2, 2015. | |

United States Postal Service Packaging Instructions [webpage on the Internet]. Washington DC: United States Postal Service; 2015. Available from: http://pe.usps.com/widgets/hyperlinking/highlighted-viewserver.jsp?id=363&title=USPSPackagingInstruction6C&url=56.42.48.42%3A9080%2Ftext%2Fpub52%2Fpub52apxc_018.htm&links=UN3373–hit0. Accessed May 2, 2015. | |

Kanack K, Amiott E, Nolte F, et al. Analytical and Clinical Evaluation of the FilmArray® Respiratory Panel. 2010. Available from: http://biofiredx.com/media/Analytical-and-Clinical-Evaluation-of-the-FilmArray-Respiratory-Panel-pstr.pdf. Accessed October 27, 2015. | |

Alsaleh AN, Whiley DM, Bialasiewicz S, et al. Nasal swab samples and real-time polymerase chain reaction assays in community-based, longitudinal studies of respiratory viruses: the importance of sample integrity and quality control. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:1. | |

Suess T, Remschmidt C, Schink SB, et al. Comparison of shedding characteristics of seasonal Influenza virus (sub)types and influenza A(H1N1)pdm09; Germany, 2007–2011. PLoS One. 2012;7(12). | |

Papenburg J, Baz M, Hamelin ME, et al. Household transmission of the 2009 pandemic A/H1N1 influenza virus: elevated laboratory-confirmed secondary attack rates and evidence of asymptomatic infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(9):1033–1041. | |

Jackson ML, France AM, Hancock K, et al. Serologically confirmed household transmission of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus during the first pandemic wave – New York City, April-May 2009. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(5):455–462. | |

Cooper DL, Smith GE, Chinemana F, et al. Linking syndromic surveillance with virological self-sampling. Epidemiol Infect. 2008; 136(2):222–224. | |

Ip DK, Schutten M, Fang VJ, et al. Validation of self-swab for virologic confirmation of influenza virus infections in a community setting. J Infect Dis. 2012;205(4):631–634. | |

Esposito S, Molteni CG, Daleno C, et al. Collection by trained pediatricians or parents of mid-turbinate nasal flocked swabs for the detection of influenza viruses in childhood. Virol J. 2010;7:85. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.