Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

Organizational Error Tolerance and Change-Oriented Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Mediating Role of Psychological Empowerment and Moderating Role of Public Service Motivation

Received 19 July 2023

Accepted for publication 7 October 2023

Published 12 October 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 4133—4153

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S431373

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Mei-Chun Cheung

Mi Lin,* Menghua Xie,* Zhi Li

School of Public Policy and Administration, Chongqing University, Chongqing, People’s Republic of China

*These authors contributed equally to this work

Correspondence: Zhi Li, Email [email protected]

Purpose: Error management is an important element of organizational management research, and organizational error tolerance has gradually received attention from researchers in recent years. Most previous studies concluded that organizational error tolerance positively affects both the perceived organizational support and job performance of public sector employees, but few have examined the relationship between organizational error tolerance and change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior.

Methods: This research examines how organizational error tolerance affects change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior using an experimental approach (Study 1, N = 162 and Study 2, N = 228) and a field survey approach (Study 3, N = 377).

Results: The results indicate that organizational error tolerance increases psychological empowerment, which in turn increases change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior. Public service motivation plays a moderating role in this process. Specifically, the positive mediating effect of organizational error tolerance on change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior through psychological empowerment was not significant when the level of public service motivation was high, while it was significant when the level of public service motivation was low.

Conclusion: This study clarifies the mechanism and boundary conditions of the effect of organizational error tolerance on change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior, provides a more comprehensive and dialectical perspective for research on organizational error tolerance, and extends research on psychological empowerment and change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior.

Keywords: organizational error tolerance, psychological empowerment, change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior, public service motivation, organizational management, employee behavior

Introduction

The digital economy presents new challenges and opportunities for the public sector, which must constantly adapt to changes in the socioeconomic and technological environment. Innovation is crucial for the public sector to adapt to a changing environment1 and is a contributing factor to the quality of public services and problem-solving capabilities.2 Effectively motivating change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) among employees in the context of innovation is an important theoretical and practical issue to address the complex environment currently faced by the public sector.3 Change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior (CO-OCB) involves employees’ spontaneous participation in organizational change by proactively suggesting and taking positive actions to optimize the organization’s work processes and methods.4 The generation and realization of employee suggestions for optimization are beneficial for improving organizational performance,5 enabling continuous organizational development,6 and providing an effective response to increasing customer expectations and market changes.7 Therefore, identifying and promoting employees’ CO-OCB factors is crucial for the public sector.

Studies have examined the prediction of CO-OCB by workplace characteristics such as procedural justice4 leader-member exchange relationships,8 and perceived organizational support.9 Choi4 emphasizes that CO-OCB can be promoted within organizations through supportive leadership and an innovative atmosphere. Therefore, to improve employees’ CO-OCB, this study argues that it is crucial to create an error-tolerant work climate in an organization to create a supportive and innovative work environment and to develop superior knowledge without fear of the consequences of making mistakes. Research has shown that in organizations with high error tolerance, employees are allowed to engage in innovative activities at work without fear of failure, thereby satisfying the need for employee support.10 This shows that changes in employee attitudes and behaviors stem from the perception of organizational error tolerance. Therefore, this study concludes that there is a positive relationship between organizational error tolerance (OET) and CO-OCB.

CO-OCB is a risk-taking behavior in which employees may challenge the status quo and attempt to make constructive suggestions and changes in their work procedures and methods. Employees are motivated when they believe that the organization allows risky work behaviors and allows them to take risks,11 when they believe that they are empowered and autonomous, and when they experience increased psychological empowerment.12 Employees who believe they are empowered are also more articulate in their use of capabilities and resources, and they are more likely to engage in change-oriented behaviors at work.13 Therefore, this study examined how organizational error tolerance affects CO-OCB through psychological empowerment. Complex interactions between individual characteristics and the work environment determine work outcomes.14 In the public sector context, public service motivation (PSM) is often viewed as an important individual characteristic that leads to positive work outcomes (eg work engagement;15 work performance16) for public sector employees and is an important factor influencing employees’ organizational citizenship behavior.17 Therefore, this study examined how PSM affects the relationship between organizational error tolerance and psychological empowerment (CO-OCB).

Based on the above discussion, we propose and test a theoretical framework (eg Figure 1) that explains how and when organizational error tolerance promotes CO-OCB among public sector employees. The theoretical and practical implications of this study are twofold: first, this study introduces organizational error tolerance as an organizational factor that predicts CO-OCB. Prior research found that error tolerance in error management cultures and environments has favorable effects on individual work-related behaviors such as innovation,18 job performance,19 but we still know little about how employees’ perceptions of organizational error tolerance affect important work attitudes and behaviors. This study used a scenario-based experimental approach to validate the mechanism of organizational error tolerance in CO-OCB, which is an extension and enrichment of the research area on the mechanism of CO-OCB influence. Second, research has shown that the degree of influence of the organizational environment on employee behavior may depend on individual differences,20 and this study introduces PSM as a moderating variable based on the characteristics of the public sector. Thus, we tested the relationship between PSM and organizational error tolerance on CO-OCB, bridging the gap in the relationship between PSM and CO-OCB and expanding the boundary conditions of CO-OCB.

|

Figure 1 The theoretical model for this study. |

Organizational Error Tolerance and CO-OCB

Errors in the service industry are often difficult to accept due to high customer expectations.21 However, recent research has concluded that errors are inevitable and that effective error management is critical to organizational success.22 This approach emphasizes the steps to be taken after an error occurs and suggests various error-handling behaviors.23 An error management climate, on the other hand, applies the principles and practices of error management to processes in the organization, including discussing and sharing information about errors with colleagues, improving the ability to analyze and resolve errors, and asking for help when an error occurs,24 and is critical to reducing negative errors and promoting positive error consequences.25 Organizational error tolerance is at the heart of error management approaches26 and is defined as the condition that exists in an organization that allows its members to take risks, seek innovative solutions, and develop superior knowledge without fear of the consequences of making a mistake,27 with an emphasis on the organization’s tolerance of errors. In organizations with high fault tolerance, mistakes are not perceived negatively and risk-taking is allowed. Error tolerance is characterized by a work environment that meets the needs of employees to protect vulnerability and supportiveness.12

The development of science and technology and the increase in public demand place higher demands on public organizations to be innovative,28 which requires employees to display more CO-OCB.29 Studies have shown that work environment characteristics significantly predict CO-OCB,4 and we suggest that employees’ CO-OCB is influenced by organizational error tolerance. This is evidenced by the fact that, on the one hand, leaders in organizations with high organizational error tolerance tend to be more inclusive in the workplace.30 Research has shown that inclusive leadership promotes employees’ CO-OCB.31 In addition, organizational tolerance encourages employees to try new things and emphasizes the importance of pursuing innovative ideas without fear of failure or potential behaviors. The risk of risk-taking behavior of employees is reduced, which promotes CO-OCB.32 On the other hand, according to social interaction theory,33 the provision of resources by an organization induces rewarding behaviors in employees. Employees in organizations with high error tolerance experience greater discretion and trust in their work. As a result of reciprocity, employees actively participate in their work and suggest and adopt optimization measures as a reward to the organization.24 Based on this, this study argues that a public sector with high organizational error tolerance is more likely to motivate employees to exhibit CO-OCB, and therefore proposes the following hypothesis:

H1: organizational error tolerance has a positive effect on CO-OCB.

The Mediating Role of Psychological Empowerment

Employee’s psychological empowerment is influenced by an individual’s perception of the organizational climate.34 The concept of employee psychological empowerment comprises four fundamental dimensions aspects: meaning, competence, influence, and autonomy. Meaning refers to the extent to which employees perceive the value of the job or task; competence refers to the employee’s belief that he or she has the skills necessary to perform different tasks; autonomy refers to the discretion employees have while working; and influence refers to the employee’s perceived impact on the immediate work environment.35 Research has shown that both organizational support and trust promote employee psychological empowerment.14,36

Thus, employees’ perceptions of their organization are key factors in psychological empowerment. Organizational error tolerance is essentially an employee’s perception of the organization’s error tolerance. By creating an error-tolerant work environment, the organization makes employees feel supported and trusted by the organization, thus stimulating their sense of psychological empowerment. Moreover, high organizational error tolerance allows employees to make mistakes to a certain extent, which means that more discretion is given to employees and increases their level of psychological empowerment. By allowing employees to speak up, organizations ensure that they have the resources to initiate and make novel suggestions, thus leading them to participate in work decisions and increasing their confidence in performing certain tasks.37 Based on this, this study argues that public sector employees with high organizational error tolerance are more likely to experience psychological empowerment and therefore proposes the following hypothesis:

H2: organizational error tolerance has a positive effect on psychological empowerment.

Psychological empowerment, defined as intrinsic motivation,38 argues that employees’ intrinsic perceptions of empowering behaviors can have a motivational effect. The impact of psychological empowerment on employee’s workplace behaviors has received considerable attention from scholars. Studies have shown that psychological empowerment enhances employees’ work behaviors such as job performance,12 work engagement,39 and organizational citizenship behaviors.40

From a social exchange perspective, when employees have higher levels of psychological empowerment, their feelings toward the organization are more positive, and, in turn, they exhibit more organizational citizenship behaviors in return. Because empowered employees perceive themselves as having the ability to influence their work and work environment meaningfully, they are more likely to take the initiative to perform duties beyond the requirements of their jobs.41 When employees have a higher perception of psychological empowerment, they have more freedom at work and are more inclined to solve difficulties.42 In addition, psychological empowerment is a personal resource,43 and when employees have high levels of perceived psychological empowerment, they have sufficient psychological resources to mitigate the depletion of intrinsic resources due to challenging behaviors. At the same time, employees with high psychological empowerment are more aware of the meaning of their work and their ability to get the job done, which can lead to an inspired work ethic and more confidence in taking charge and solving challenging tasks,39 and employees are more likely to engage in transformative organizational citizenship behaviors. Based on this, this study argues that highly psychologically empowered public sector employees are more likely to exhibit high CO-OCB, and therefore proposes the following hypothesis:

H3: Psychological empowerment has a positive effect on CO-OCB.

In summary, this study argues that high organizational error tolerance allows employees to pursue innovative ideas and program implementation at work without fear of the consequences of making mistakes, which allows them to experience higher levels of psychological empowerment at work and to be more likely to generate and implement novel work ideas, thus effectively motivating their CO-OCB. In combination with H2 and H3, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4: Psychological empowerment mediates the relationship between organizational error tolerance and employee’s CO-OCB.

Moderating Effect of PSM

Public service motivation (PSM) is a universal altruistic motivation that refers to the tendency of individuals to be motivated primarily by the public sector or organization44 and emphasizes the beliefs, values, and attitudes of individuals to serve the interests of society beyond personal and organizational interests.45 Early research suggests that PSM consists of four dimensions: attraction to policymaking, commitment to the public good, self-sacrifice, and compassion.46 Among them, attraction to politics is expressed as an individual’s interest in politics and policy, commitment to the public interest is expressed as a strong willingness and desire to serve the public interest, compassion is expressed as an emotional response that motivates individuals to care for or protect others or society in a particular context, and self-sacrifice is expressed as a willingness to sacrifice personal interests for others or the public interest.47 Public service motivation has been demonstrated to be related to public sector employees’ job performance, including job satisfaction,48 job performance,16 willingness to leave,49 organizational citizenship behavior,50 and innovative work behavior.51

This study argues that there is a moderating effect of PSM between organizational error tolerance and psychological empowerment. First, the perceived meaningfulness of work brought about by psychological empowerment will facilitate the fit between employees’ personal values and organizational goals.52 Employees with high PSM will emphasize the importance of meaningful work and service to society compared to those with low PSM,53 and will tend to spend more time and energy working and finding and creatively solving problems. They tend to devote more time and energy to their work and identify and solve problems creatively. Therefore, employees with high PSM have a stronger perception of the meaning of their work and are less disturbed by organizational factors. Second, PSM reflects the intrinsic needs of individuals who desire to serve society54 and create social value through their actions.50 Public sector employees tend to believe that they are competent to provide public services. Third, in terms of the autonomy dimension, PSM is a key factor for public-sector employees to work autonomously and hard, be self-directed, and devote their energy to purposeful actions.55 Fourth, in the influence dimension, public service-driven employees are willing to maximize their work efforts to enhance organizational goals when they feel that their actions are important in promoting organizational development,56 and their perception of work influence does not diminish even when the organization’s error-tolerance resources are insufficient. Based on the above analysis, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H5: PSM moderates the relationship between organizational error tolerance and psychological empowerment; the positive relationship between organizational error tolerance and psychological empowerment is attenuated under the influence of high PSM relative to low levels of PSM.

It has been noted that there is a substitution effect between the influence of PSM on individuals in the organizational setting.20 In other words, the principle of reciprocity has less influence on individuals with high PSM than on those with low PSM. This may be because employees with high PSM value the intrinsic rewards of their work more and can compensate for the lack of external incentives. In the public sector, PSM drives employees to work positively and energetically, even in the face of strict organizational procedures, and to try different options to solve problems.57 Conversely, individuals with weak PSM are not sufficiently self-directed to contribute to the organization and are more dependent on the resources provided by the organization. Only when the organization provides sufficient error tolerance guarantees to ensure adequate resources for individuals, based on the principle of reciprocity, will individuals with low PSM exhibit more CO-OCB that drives organizational development. Additionally, employees with high PSM may overemphasize integration into public organizations and require a lot of energy to perform public service work at work, which will drain their enthusiasm,58 leaving them feeling exhausted and stressed, thus making it difficult to have the energy and enthusiasm to perform CO-OCB.

Based on the above analysis, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H6: PSM moderates the relationship between organizational tolerance and CO-OCB; that is, the positive relationship between organizational tolerance and CO-OCB will be attenuated under the influence of high PSM relative to low levels of PSM.

In summary, because psychological empowerment mediates the relationship between organizational tolerance and CO-OCB (H4) and the relationship between organizational tolerance and psychological empowerment is moderated by PSM (Hypothesis H5), we expected PSM to play a moderating role in determining the strength of the indirect relationship between organizational tolerance and CO-OCB through psychological empowerment. This indirect relationship was expected to be weaker when PSM was high. Therefore, the research hypothesis pf this study includes a moderated mediation process. The specific hypotheses are as follows:

H7: The indirect effect of organizational error tolerance on CO-OCB through psychological empowerment is moderated by PSM; the indirect relationship is weaker when PSM is high but stronger when PSM is low.

Study 1 an Experimental Study of Organizational Error Tolerance on Psychological Empowerment, Change-Oriented Organizational Citizenship Behavior

Study 1 was a scenario-based experiment with a sample of public-sector employees. In Study 1, we tested whether psychological empowerment and CO-OCB increased by manipulating organizational error tolerance to test H1, H2, H3, and H4.

Research Methodology

Research Sample

To facilitate the survey, we recruited 162 public sector employees from different regions of China to complete the experiment through Credamo, an online survey platform in China that provides the functional equivalent of the MTurk platform and demonstrates the reliability of the data collected through the MTurk platform.59 Of the participants, 53.1% were women, 55.6% were aged 35 years or younger, 57.4% had a bachelor’s degree, and 42.6% had a graduate degree.

Experimental Design and Procedures

First, all participants completed a questionnaire that included measures of OET, psychological empowerment, CO-OCB, and participant demographic variables. Subsequently, all participants were randomly assigned to either a high OET group (n = 81) or a low OET group (n = 81), and participant in both groups OET scores (t = −1.12, p = 0.265>0.05), psychological empowerment scores (t = −0.737, p = 0.462>0.05), and CO-OCB scores (t = −0.671, p = 0.503 >0.05) were not significantly different. Participants in both groups were asked to read a passage of scenario material. After completing the reading task, participants were asked to recall and describe in detail the content of the material, followed by the completion of a questionnaire that included measures of OET, psychological empowerment, and CO-OCB.

Manipulation Procedure for Organizational Error Tolerance

In the high organizational error tolerance group, we provided a piece of material describing the work climate in Township A and asked participants to imagine as much as possible that they were the main character in the material: Chen, an employee in Township A. The content of the material was adapted from manipulation procedures in existing studies60 and combined with organizational error tolerance scales27 with questions such as “Leaders tolerate mistakes when employees pursue innovative solutions” and “The company understands that making mistakes is part of taking risks.” Participants in the high organizational error tolerance condition received the following manipulated scenario:

The atmosphere in your organization is very enlightened, where minor mistakes are understood as long as they are not matters of principle, and objections or dissenting opinions are accepted as long as these things are not intentionally or repetitively harmful to the organization. Your superior is a person who pays attention to pioneering and innovation, and he often encourages his subordinates not to be afraid of making mistakes on the road to change and innovation and to be brave enough to explore and try. Your colleagues around you are active and aggressive at work, always thinking of ways to get the job done, and can take on and solve problems together when they encounter difficulties and make mistakes in their work. You will get the understanding of your superiors and colleagues for some small shortcomings and mistakes in your work.

Participants in the low organizational error tolerance condition received the following manipulated scenario: “The management requirements of your organization are very strict, and employees are punished for small mistakes they make at work. Few people will object or disagree with the ideas proposed by the organization or the leader. Your superior is a careful and cautious person who often emphasizes that his subordinates should strictly follow the system norms at work and should not make mistakes at work. Your colleagues around you in the work uphold the “more is better than less” thinking, in the work of the rules, but also “crowd out” in the work of those who do not follow the rules, afraid to follow the bad luck. You are often criticized and blamed by your superiors and colleagues for some minor shortcomings and mistakes in your work.”

Measurement Tools

We made slight modifications to the wording of the items, following Brislin’s61 two-way translation-back-translation procedure to ensure that the scales were adapted to research in our organizational context.

Psychological empowerment. The scale, proposed by Spreitzer38 and translated by Li and Shi,62 has been validated and applied by many scholars. The scale consists of 12 items, such as “In such an organization, I have a lot of autonomy in deciding how to do my job”, and “In such an organization, I can acquire all the skills I need to do my job”. The scale was scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = very non-conforming, 5 = very conforming), and the internal consistency coefficient α of the scale was 0.962.

CO-OCB: using the measurement tool developed by Vigoda-Gadot and Beeri,63 including “In such an organization, I try to correct inappropriate or erroneous work processes and practices in my organization”, “In such an organization, I try hard to adopt improved processes in my work”, and other 9 items. A 5-point Likert scale was used (1 = very non-conforming, 5 = very conforming), and the internal consistency coefficient α of the scale was 0.976.

Manipulation test: Organizational error tolerance: the scale developed by Weinzimmer and Esken27 was used to measure organizational tolerance for error, with five questions, including “In an organization where leaders tolerate mistakes as I/colleagues pursue innovative solutions” and “In an organization where leaders understand that making mistakes is part of the adventure”. The scale is based on a 5-point Likert scale. A 5-point Likert scale was used (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), and the internal consistency coefficient α of the scale was 0.939.

Study Results

Manipulation Check

First, the experimental manipulation was tested. The t-test showed that participants in the high organizational error tolerance group had significantly higher organizational error tolerance scores after reading the material (M = 4.31, SD = 0.39) than before reading the material (M = 3.11, SD = 0.96), t(81) = 10.435, p = < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.64. Participants in the low organizational error tolerance group had significantly lower organizational error tolerance scores after reading the material (M = 2.27, SD = 0.62) than before reading the material (M = 3.27, SD = 0.62), t(81) = 8.132, p =< 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.61.

After reading the material, participants in the high organizational error tolerance group had significantly different organizational error tolerance scores than those in the low organizational error tolerance group, t(162) = 25.180, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 3.94. Thus, Study 1 successfully manipulated OET.

Hypothesis Testing

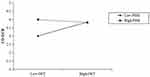

We used t-tests for the hypothesis analysis and found that Participants in the high organizational error tolerance group had significantly higher CO-OCB scores after reading the material (M = 3.98, SD = 0.80) than before reading the material (M = 3.46, SD = 1.14), t(81) = 3.356, p = < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.53. Participants in the low organizational error tolerance group had significantly lower CO-OCB scores after reading the material (M = 2.79, SD = 0.98) than before reading the material (M = 3.58, SD = 1.09), t(81) = 4.823, p = < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.76. In addition, participants in the high organizational error tolerance group scored significantly differently on CO-OCB than participants in the low organizational error tolerance group, t(162) = 8.582, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.33.

Therefore, Hypothesis 1 was verified. Specifically, as shown in Figure 2.

|

Figure 2 Effect of organizational error tolerance on CO-OCB. Abbreviations: OET, Organizational error tolerance; CO-OCB, Change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior. |

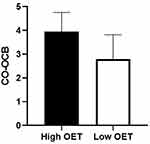

Participants in the high organizational error tolerance group had significantly higher psychological empowerment scores after reading the material (M = 3.77, SD = 0.83) than before reading the material (M = 3.43, SD = 1.14), t(81) = 2.158, p = 0.032 < 0.05, Cohen’s d = 0.34. Participants in the low organizational error tolerance group had significantly lower psychological empowerment scores after reading the material (M = 2.65, SD = 0.86) than before reading the material (M = 3.56, SD = 1.08), t(81) = 5.955, p = < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.93. Additionally, participants in the high organizational error tolerance group scored significantly differently on psychological empowerment than participants in the low organizational error tolerance group, t(162) = 8.457, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.33.

Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was confirmed. This is specifically shown in Figure 3.

|

Figure 3 Impact of organizational error tolerance on psychological empowerment. Abbreviations: OET, Organizational error tolerance; PE, Psychological empowerment. |

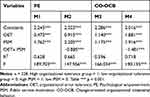

Correlation analyses of psychological empowerment and CO-OCB showed that r = 0.89, p < 0.001, indicating a significant correlation. General linear regression analysis was used to test H3 and H4, and the results are shown in Table 1. From Model 1, psychological authorization significantly affected CO-OCB (b = 0.945, p < 0.001), and H3 was verified. From Model 2, the dependent variable CO-OCB regressed on both the independent variable OET and the mediator variable psychological empowerment, with a significant coefficient on OET (b = 0.187, p < 0.05) and a significant coefficient on psychological empowerment (b = 0.893, p < 0.001). Psychological authorization partially mediated between OET and CO-OCB and H4 was supported. In addition, this study applied the SPSS plug-in PROCESS macro to test the mediating role, with a bootstrap replicated sampling number of 5000. the run results showed that psychological empowerment was included in the model analysis, and the direct effect of organizational error tolerance on CO-OCB = 0.187, SE = 0.091, with a 95% confidence interval CI = [0.0071, 0.3663] (excluding zeros); indirect effect = 1.003, SE = 0.128, 95% confidence interval CI = [0.7568, 1.2673] (excluding zeros). The results suggest that psychological empowerment mediates the relationship between OET and CO-OCB.

|

Table 1 General Linear Regression Results (Study 1) |

Study 2 Experimental Study to Investigate the Regulatory Effect of PSM

To clarify the moderating role of PSM, we examined whether the interaction between organizational error tolerance and PSM affects psychological empowerment and CO-OCB. Study 2 was a scenario-based experiment with a sample of public-sector employees. In Study 2, we manipulated organizational error tolerance and PSM to test whether their interaction increased psychological empowerment and CO-OCB, thus testing H5, H6, and H7.

Research Methodology

Research Sample

We recruited 380 public sector employees from different regions of China and completed an experiment using Credamo, an online survey platform. Of the participants, 51.1% were women, 56.8% were aged 35 years or younger, 63.7% had a bachelor’s degree or less, and 36.3% had a graduate degree.

Experimental Design and Procedures

A 2×2 two-factor between-subject design was used. All participants were first asked to complete the PSM measurement questionnaire and were then ranked according to their PSM scores; the top 30% of participants with PSM scores (n = 114) were selected as the high PSM group and participants in the bottom 30% of PSM scores (n = 114) were selected as the low-PSM group. The t-test results showed that the scores in the high PSM group (M = 4.57, SD = 0.17) were significantly higher than those of the participants in the low PSM group (M = 2.64, SD = 1.01), t(228) = 20.181, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 2.66.

Then, participants in the high PSM group were randomly assigned to either the high (n = 57) or the low (n = 57) organizational error tolerance group. Participants in the low PSM group were randomly assigned to either the high (n = 57) or low (n = 57) organizational error tolerance groups. All four groups were asked to read a piece of material.

Manipulation of organizational error tolerance: The manipulation of organizational error tolerance is divided into high and low organizational error tolerance groups. This manipulation procedure was consistent with that used in Study 1.

Measurement Tools

Psychological Empowerment: Consistent with Study 1. The internal consistency coefficient α of the scale was 0.970.

Change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior: Consistent with Study 1. The internal consistency coefficient α of the scale was 0.962.

PSM: The 5-item scale developed by Wright et al64 was used to measure motivation for public service, with representative items such as “It is more important for me to be able to contribute to society than to achieve personally” and “I will fight for the rights of others even if I am ridiculed”. The scale was scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), and the internal consistency coefficient α of the scale was 0.935.

Manipulation test: Organizational error tolerance is consistent with Study 1. The internal consistency coefficient α of the scale was 0.979.

Study Results

Manipulation Check

First, the experimental manipulation was tested. Participants in the high organizational error tolerance group scored significantly higher (M = 3.73, SD = 1.11) than those in the low organizational error tolerance group (M = 3.06, SD = 1.29; t(114) = 4.219, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.12). Thus, Study 2 was successful in manipulating organizational error tolerance.

Hypothesis Testing

The four experimental groups were subjected to descriptive statistics and ANOVA with post hoc analysis, and the results are shown in Table 2. The results showed that the four experimental groups differed significantly in psychological empowerment (F = 147.956, p < 0.001, partial eta squared = 0.665) and CO-COB (F = 190.155, p < 0.001, partial eta squared = 0.718).

|

Table 2 Analysis of Variance Results |

Correlation analyses of psychological empowerment and CO-OCB showed that r = 0.73, p < 0.001, indicating a significant correlation. General linear regression analysis was used to test H5 and H6, and the results are presented in Table 3. As shown in Table 3, Model 2, the interaction term between organizational error tolerance and PSM significantly affected psychological empowerment (b = −0.885, p < 0.001). When PSM was low, the psychological empowerment score of the high organizational error tolerance group (M = 2.94, SD = 1.16) was significantly higher than that of the low organizational error tolerance group (M = 2.02, SD = 0.63), t(114) = 5.241, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.99; when PSM was high, the psychological empowerment score of the high organizational error tolerance group (M = 4.26, SD = 0.19) was not significantly different from the low organizational error tolerance group (M = 4.23, SD = 0.19), t(114) = 0.865, p = 0.392 > 0.05, Cohen’s d = 0.16. This is shown in Figure 4. Thus, Hypothesis 5 was verified.

|

Table 3 General Linear Regression Results (Study 2) |

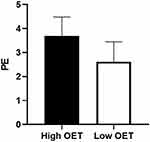

As shown in Model 4 of Table 3, the interaction terms of organizational error tolerance and PSM significantly affected CO-OCB (b = −1.481, p < 0.001). When the PSM was low, the CO-OCB score was significantly higher in the high organizational error tolerance group (M = 3.90, SD = 0.54) than in the low organizational error tolerance group (M = 2.02, SD = 0.57), t(114) = 18.081, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 3.39; when PSM was high, the CO-OCB scores were significantly higher in the high organizational error tolerance group (M = 4.33, SD = 0.19) than in the low organizational error tolerance group (M = 3.93, SD = 0.80), t(114) = 3.674, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.69. as shown in Figure 5. Thus, Hypothesis 6 was confirmed.

In this study, the SPSS PROCESS macro was applied to test H7, and the results are shown in Table 4, the running results show that the mediated effect index with moderation is −0.3043, SE = 0.0832, 95% confidence interval CI = [−0.4847, −0.1579] (excluding 0), which means that there is a significant mediated effect with moderation in favor of H7.

|

Table 4 Mediation Tests with Moderation (Study 2) |

Study 3 Full Model Questionnaire Research

Studies 1 and 2 provided strong causal evidence for the role of organizational error tolerance in psychological empowerment and CO-OCB and tested the moderating effect of PSM on the relationship between organizational error tolerance, psychological empowerment, and CO-OCB. Both studies validated the internal validity of the theoretical model but were limited in terms of external validity. Therefore, we extend the external validity of our findings to Study 3 by testing the overall research model using a multi-source questionnaire.

Research Sample

The survey was distributed electronically to public sector employees in China, and 1000 questionnaires were distributed to them. After eliminating questionnaires with missing data, identical answers to scale questions, and those with a short response time (less than 500 s), 937 valid questionnaires were returned, for a valid response rate of 93.7%. All questionnaires were completed anonymously and voluntarily, and a strict confidentiality system was implemented to ensure the truthfulness and objectivity of the data obtained. Among the participants, 459 (49.0%) were male and 478 (51.0%) were women; in terms of age, 94 (10.0%) were under 25 years old, 380 (40.6%) were 26–35 years old, 286 (30.5%) were 36–45 years old, 146 (15.6%) were 46–55 years old, and 31 people (3.3%); 124 people (14.3%) had less than bachelor’s degree, 499 people (53.3%) had a bachelor’s degree, and 304 people (32.4%) had a postgraduate degree.

Measurements

- Organizational error tolerance. Consistent with Study 1. The internal consistency coefficient α of the scale was 0.939.

- Psychological empowerment. Consistent with Study 1. The internal consistency coefficient α of the scale was 0.954.

- Change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior. Consistent with Study 1. The internal consistency coefficient α of the scale was 0.933.

- PSM was consistent with Study 2. The internal consistency coefficient α of the scale was 0.931.

Statistical Analysis Methods

In this study, SPSS 25.0, PROCESS plug-in, and AMOS 24.0 were used to analyze the sample data. First, the discriminant validity among the variables was tested by validating factor analysis, and the homophily bias problem was tested by Harman’s one-way test and the common method latent factor method. Then, the effect of organizational error tolerance on CO-OCB, the mediating effect of psychological empowerment, and the moderating effect of PSM were tested by stratified regression analysis. Finally, the bootstrap method was used to estimate the 95% confidence interval effect values to test the moderated mediation.

Analysis and Results

Validation Factor Analysis and Common Method Deviation Test

This study used Amos 24.0, to perform a validated factor analysis on four variables: organizational error tolerance, psychological empowerment, CO-OCB, and PSM; the results are shown in Table 5. The data from the four-factor model fit best compared to the other three competing models (X2 /df = 1.415, CFI = 0.992, GFI = 0.961, RMSEA = 0.021, SRMR = 0.0258), indicating that the four variables examined in this study have good discriminant validity and are four distinct constructs.

|

Table 5 Validity Analysis Table |

In this study, all variables were measured using a self-reported questionnaire; therefore, there may have been common method bias. To ensure rigor, we used Harman’s one-way test, and the results showed that there were four factors with characteristic roots greater than one. The variance explained by the largest factor was 38.757% (less than 40%); therefore, there was no serious common method bias. In addition, this study tested the changes in the model fit indicators after adding the common method latent factor. As shown in Table 5, the decreases in RMSEA and SRMR after adding CMV were much less than 0.5, and there was no significant change in the five-factor model fit index. The above analysis indicated that the common method bias was not significant in this study.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis of Each Variable

Correlation analysis was conducted for organizational error tolerance, psychological empowerment, CO-OCB, and PSM. The correlation values and significance levels between the variables are shown in Table 6.

|

Table 6 Descriptive Statistical Results and Correlation Analysis of the Main Variables |

SPSS (version 25.0) was used to perform a stratified regression analysis of the data, and the results are presented in Table 7. Model 4 showed a significant positive effect of organizational error tolerance on CO-OCB (b = 0.264, p < 0.001), supporting H1. Model 1 showed a significant positive effect of organizational error tolerance on psychological empowerment (b = 0.282, p < 0.001), supporting H2. Model 5 shows a significant positive effect of psychological empowerment on CO-OCB (b = 0.346, p < 0.001), and hypothesis H3 was supported.

|

Table 7 Stratified Regression Analysis |

Model 6 showed that the dependent variable CO-OCB was regressed on both the independent variable error tolerance and the mediating variable psychological, with significant coefficients for organizational error tolerance (b = 0.183, p < 0.001) and psychological empowerment (b = 0.286, p < 0.001). Psychological empowerment partially mediates the relationship between organizational error tolerance and CO-OCB, and H4 was supported. In addition, the SPSS plug-in PROCESS macro was used to test the mediating role, with a bootstrap repeated sample of 5000. The results showed that psychological empowerment was included in the model analysis, with a direct effect of organizational error tolerance on CO-OCB of 0.218, SE = 0.028, 95% confidence interval CI = [0.1622, 0.2735] (excluding 0), and an indirect effect of 0.110, SE = 0.020, 95% confidence interval CI = [0.0750, 0.1495] (excluding 0). These results suggest that psychological empowerment mediates the relationship between organizational error tolerance and CO-OCB. H4 was supported.

To test the moderating effect of PSM on the relationship between organizational tolerance and psychological empowerment, the interaction term was obtained by first centralizing organizational error tolerance and PSM, multiplying centralized organizational error tolerance by PSM, and then conducting a stratified regression test. The results are presented in Model 3 of Table 7. After controlling for the main effects of organizational error tolerance and psychological empowerment, the interaction between both organizational error tolerance and PSM has a significant effect on psychological empowerment (b = −0.269, p < 0.001), indicating that the moderating effect of PSM on the relationship between organizational error tolerance and psychological empowerment is significant. H5 was supported.

A further simple slope analysis was conducted to plot the interaction of the moderating variable public service motivation at high and low levels (mean plus or minus one standard deviation, respectively). As shown in Figure 6, at low levels of PSM, the positive predictive coefficient of organizational error tolerance for psychological empowerment was (b = 0.662, p < 0.001), while at high levels of PSM, the positive predictive coefficient of organizational error tolerance for psychological empowerment was not significant (b = 0.029, p = 0.723>0.05). These results suggest that this negative relationship is attenuated as the level of PSM increases.

Model 8 in Table 7 presents the results of examining the moderating effect of PSM on the relationship between organizational error tolerance and CO-OCB. After controlling for the main effects of organizational error tolerance and CO-OCB, the interaction of both organizational error tolerance and PSM had a significant effect on CO-OCB (b = −0.234, p < 0.001), indicating the moderating effect of PSM on the relationship between organizational error tolerance and CO-OCB. The moderating effect is significant. H6 was supported.

A further simple slope analysis was conducted to plot the interactions by dividing the moderating variable public service motivation into high and low levels (mean plus or minus one standard deviation, respectively). As shown in Figure 7, at low levels of PSM, the positive predictive coefficient significantly (b = 0.637, p < 0.001) predicted a positive effect of organizational error tolerance on CO-OCB; at high levels of PSM, the positive predictive coefficient of organizational error tolerance on CO-OCB was not significant (b = −0.031, p = 0.695 > 0.05). These results suggest that at increasing levels of PSM, the positive relationship between organizational error tolerance and CO-OCB was attenuated.

In addition, this study used the SPSS PROCESS macro to test the mediation effect with moderation. The results are shown in Table 8, which shows that the mediation effect index with moderation is −0.0456, SE = 0.0132, 95% confidence interval CI = [−0.0723, −0.0199] (excluding 0), which indicates that the mediation effect with moderation is significant and supports H7.

|

Table 8 Mediation Tests with Moderation |

Discussion

This study constructed a moderated mediation model for public sector employees through two experimental studies and one questionnaire study to examine the effects of organizational error tolerance on CO-OCB, the mediating role of psychological empowerment, and the moderating role of PSM. High organizational error tolerance was found to enable employees to experience higher psychological empowerment and exhibit higher CO-OCB. The positive effect of high organizational error tolerance on psychological empowerment and CO-OCB was moderated by individual characteristics of high PSM, while the indirect effect of organizational error tolerance on CO-OCB was attenuated.

Theoretical Contributions

First, it attempts to link organizational error tolerance with CO-OCB to create new working conditions for promoting CO-OCB among public sector employees. The results showed that organizational error tolerance can significantly and positively predict CO-OCB. Previous studies have shown that workplace characteristics such as team emotion65 and innovation climate4 can effectively promote CO-OCB; however, few efforts have been made to investigate the effect of organizational error tolerance on CO-OCB. Moreover, it has been widely verified that organizational error tolerance can enhance positive work attitudes, such as employee engagement66 and turnover propensity67 has been widely verified. Predictors of CO-OCB have also been studied, including organizational identity,8 empowering leadership,68, and the impact of organizational error tolerance on CO-OCB. However there is a lack of research on the relationship between organizational error tolerance and CO-OCB, which have developed independently, and both organizational error tolerance and CO-OCB contribute to positive work outcomes in the public sector, such as improved organizational performance.4,27 Therefore, this study extends the research on CO-OCB in the public sector by examining the possible predictive role of organizational error tolerance on CO-OCB in an organizational context, a finding that helps elucidate the underexplored relationship between organizational error tolerance and CO-OCB.

Second, this study verifies the effect of organizational error tolerance on employees’ psychological empowerment and CO-OCB using scenario-based tests and questionnaires.

Previous research has often focused on how employees react after an error occurs,23 that is, how errors are handled in the workplace.69 Error management encourages employees to communicate errors promptly, share their knowledge of errors, and learn from their own or others’ failures.70 However, little is known about how employees’ perceptions of organizational error tolerance affect their work attitudes. The present study is consistent with Frese and Keith’s26 study, which considers organizational error tolerance as the core of organizational error management and emphasizes employees’ perceptions of organizational error tolerance. Wang et al’s24 findings suggest that employees in organizations with high error tolerance generate positive psychological resources through perceived organizational support, which in turn has a positive impact. Organizations with high error tolerance can provide employees with opportunities to learn from their mistakes and reward open communication of errors, rather than punishing those who disclose or admit them.25 This allows employees to perceive more discretion and psychological safety in the organization, thereby promoting their perception of psychological empowerment. In other words, tolerating mistakes at work not only allows employees to feel comfortable speaking up or taking risks but also enhances their self-confidence in their ability to do their jobs (eg Wang et al23). According to social exchange theory, when employees perceive organizational support, they feel obligated to return it through positive attitudes and behaviors. Furthermore, based on the job demand-resource model, employees with higher job autonomy have more job resources71 and can improve their innovative work behaviors.72

Third, we examined how individual characteristics interact with organizational factors to influence psychological empowerment and CO-OCB by introducing PSM. In this study, we validated H5, and H6, and PSM as moderators in the process of organizational error tolerance influencing psychological empowerment and CO-OCB. Previous research suggests that when employees’ attributes and preferences match the characteristics of their work environment, they tend to produce more positive work attitudes and outcomes.73 That is, the work environment is important for public service-motivated employees; as employees’ personal-organizational fit increases, employees will have more opportunities to meet their PSM needs, and these PSM needs become a key component of their hard work in the public sector.74 However, some findings suggest that PSM has a substitution effect between the effects of the organizational environment on individuals.21 Our findings suggest that PSM buffers the positive effect of organizational error tolerance on CO-OCB. We argue that employees with high PSM have positive attitudes (eg organizational commitment75) and behaviors (organizational citizenship behaviors18) that tend to be internally driven and less influenced by the external environment, and that employees with high PSM emphasize the importance of meaningful work and service to society;53 they tend to spend more time and energy on the job and identify and creatively solve problems.

Moreover, some researchers have argued that public service motivation may have negative effects on public organizations,76 for example, higher public service motivation among employees is associated with lower job satisfaction due to increased stress.77 That is, employees with higher PSM are more likely to be overburdened in the pursuit of public service, triggering energy depletion, and no excess energy or attention to exhibit OCB.78 Although PSM affects employees’ work attitudes and behaviors, it is still unclear how the interaction between organizational factors and PSM affects them. Therefore, this study clarifies the mechanisms underlying the role of PSM and validates the relationship between PSM moderating organizational error tolerance and psychological empowerment, and the CO-OCB relationship, improving our understanding of this complex relationship.

Management Insights

This study has important practical implications for the public sector. First, creating a good organizational error-tolerant climate is an effective way to promote CO-OCB. First, organizations should create an error-tolerant climate in terms of “recovery from failure” and “learning and improvement”,23 emphasizing that organizational error management is a work process and method that motivates employees to pursue innovation. At the same time, support from leaders and colleagues for error management79 is advocated to facilitate employees’ timely reporting and sharing of errors. Second, organizations should create an organizational culture that supports innovation,5 so that employees can think positively about problems, develop new ideas and solutions, and receive praise and appreciation. Organizations should also provide opportunities for employees to provide feedback so that they can see their contributions and modify and improve their behavior based on feedback. In addition, organizations should ensure, both verbally and in action, that employees know they are empowered and trusted to make decisions. In an organizational culture, employees can listen to each other, offer perspectives, and tolerate when things go wrong. Organizations should support trial and error, encourage employees to try new things, provide maximum autonomy, and encourage employees to be innovative and creative thinkers.

Second, the results show that psychological empowerment is a contributing factor to employee performance in CO-OCB. Increasing the psychological empowerment of employees is crucial in the public sector.80 Leadership style is the best predictor of psychological empowerment81. Therefore, organizational leaders should make conscious attempts to trust employees, encourage their participation in the decision-making process, and empower them psychologically. Psychological empowerment does not rely solely on the influence of organizational leaders; there is evidence that employees’ psychological security82 is necessary to promote employees’ psychological empowerment. The complementary nature of employees and leaders can increase the overall effectiveness of psychological empowerment.

Finally, this study also discusses the positive effects of organizational tolerance on psychological empowerment; the CO-OCB of public sector employees is buffered by PSM. A dialectical perspective is needed to understand the role of PSM in public service motivation. These findings suggest that employees with high PSM can adapt to different organizational characteristics, and organizations should focus on PSM development in the long run. This is because public servants with low levels of PSM may not be able to cope well with job demands such as bureaucracy.83 The public sector can activate and develop PSM of employees through management approaches such as organizational support,84 organizational commitment,85 thematic training, learning, and education. More importantly, attention should be paid to selecting employees with high levels of PSM during the recruitment process.86

Research Gaps and Outlook

First, the experiments in Studies 1 and 2 lacked a neutral control group for the OET manipulation, while actual behavior was not measured. Further future research could involve participants in real work tasks and measure their actual behaviors or conduct actual training interventions in organizations. Second, to accurately understand employees’ psychological states and situational perceptions, all data were obtained from participants’ self-reports, which may subject the findings to homogeneous data, common method bias, and social approval effects. Subsequent studies can improve measurement validity by examining the evaluations of other members within the organization to increase the rigor of the study findings. Meanwhile, because organizational tolerance, psychological empowerment levels, and public service motivation vary over time, the causal relationships among the variables cannot be accurately assessed using data collected during the same period. Subsequent studies can verify the relationship between organizational tolerance and CO-OCB through longitudinal follow-up surveys. In addition, the sample of this study was limited to government employees in China, which has some external validity problems, and the findings cannot be generalized to other cultural backgrounds or industries. Therefore, future studies should be conducted in different cultural contexts or industries to confirm the hypothesized causal relationship.

Research Findings

Our situational experiments and full-model questionnaires suggest that organizational error tolerance increases psychological empowerment and enhances CO-OCB. This study provides new evidence on the working conditions that enhance CO-OCB and shows that organizational error tolerance can effectively enhance employees’ CO-OCB by increasing psychological empowerment. PSM provides a new perspective for analyzing this process while providing the public sector with management efforts by providing theoretical recommendations and practical guidance.

Data Sharing Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Ethical Approval

The original study has been performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at Chongqing University.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in this study.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the researchers for data collection and processing. We also thank all the survey participants in our study. We would like to thank Editage for English language editing.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Raudla R, Mohr Z, Douglas JW. Which managerial reforms facilitate public sector innovation? Public Admin. 2023;1–18. doi:10.1111/padm.12951

2. De Vries H, Bekkers V, Tummers L. Innovation in the public sector: a systematic review and future research agenda. Public Admin. 2016;94(1):146–166. doi:10.1111/padm.12209

3. de Geus CJC, Ingrams A, Tummers L, Pandey SK. Organizational Citizenship Behavior in the Public Sector: a Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Agenda. Public Admin Rev. 2020;80:259–270. doi:10.1111/puar.13141

4. De Clercq D. Organizational disidentification and change-oriented citizenship behavior. Eur Manag J. 2022;40(1):90–102. doi:10.1016/j.emj.2021.02.002

5. Shanker R, Bhanugopan R, van der Heijden BIJM, Farrell M. Organizational climate for innovation and organizational performance: the mediating effect of innovative work behavior. J Vocat Behav. 2017;100:67–77. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2017.02.004

6. Janssen O, van de Vliert E, West M. The bright and dark sides of individual and group innovation: a Special Issue introduction. J Organ Behav. 2004;25(2):129–145. doi:10.1002/job.242

7. Jong AD, De Ruyter K. Adaptive versus proactive behavior in service recovery: the role of self-managing teams. Decis Sci. 2004;35(3):457–491. doi:10.1111/j.0011-7315.2004.02513.x

8. S-B H, Lee S, Byun G, Dai Y. Leader narcissism and subordinate change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior: overall justice as a moderator. Soc Behav Pers. 2020;48(7):1–12. doi:10.2224/sbp.9330

9. Ghosh R, Reio TG, Haynes RK. Mentoring and organizational citizenship behavior: estimating the mediating effects of organization-based self-esteem and affective commitment. Hum Resour Dev Q. 2012;23(1):41–63. doi:10.1002/hrdq.21121

10. Wang X, Wen X, Paşamehmetoğlu A, Guchait P. Hospitality employee’s mindfulness and its impact on creativity and customer satisfaction: the moderating role of organizational error tolerance. Int J Hosp Manag. 2021;94:102846. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102846

11. Gong Y, Cheung SY, Wang M, Huang JC. Unfolding the proactive process for creativity: integration of the employee proactivity, information exchange, and psychological safety Perspectives. J Manag. 2012;38(5):1611–1633. doi:10.1177/0149206310380250

12. Liu X, Ren X. Analysis of the mediating role of Psychological Empowerment between Perceived Leader Trust and Employee Work Performance. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(11):6712. doi:10.3390/ijerph19116712

13. Taylor J. Goal setting in the Australian public service: effects on psychological empowerment and organizational citizenship behavior. Public Admin Rev. 2013;73(3):453–464. doi:10.1111/puar.12040

14. Quratulain S, Khan AK. Red tape, resigned satisfaction, Public Service Motivation, and negative employee attitudes and behaviors: testing a model of moderated mediation. Rev Public Pers Admin. 2015;35(4):307–332. doi:10.1177/0734371X13511646

15. Ding M, Wang C. Can public service motivation increase work engagement?-A meta-analysis across cultures. Front Psychol. 2022;13:1060941. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1060941

16. Stefurak T, Morgan R, Johnson RB. The relationship of public service motivation to job satisfaction and job performance of emergency medical services professionals. Public Pers Manag. 2020;49(4):590–616. doi:10.1177/0091026020917695

17. Piatak JS, Holt SB. Disentangling altruism and public service motivation: who exhibits organizational citizenship behaviour? Public Manag Rev. 2020;22(7):949–973. doi:10.1080/14719037.2020.1740302

18. Fischer S, Frese M, Mertins JC, Hardt-Gawron JV. The role of error management culture for firm and individual innovativeness. Appl Psychol. 2018;67(3):428–453. doi:10.1111/apps.12129

19. Klamar A, Horvath D, Keith N, Frese M. Inducing error management culture – evidence from experimental team studies. Front Psychol. 2021;12:716915. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.716915

20. Potipiroon W, Faerman S. What difference do ethical leaders make? Exploring the mediating role of interpersonal justice and the moderating role of public service motivation. Int Public Manag J. 2016;19(2):171–207. doi:10.1080/10967494.2016.1141813

21. Cheng BL, Gan CC, Imrie BC, Mansori S. Service recovery, customer satisfaction and customer loyalty: evidence from Malaysia’s hotel industry. Int J Qual Serv Sci. 2019;11(2):187–203. doi:10.1108/IJQSS-09-2017-0081

22. Wang X, Guchait P, Paşamehmetoğlu A. Tolerating errors in hospitality organizations: relationships with learning behavior, error reporting and service recovery performance. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag. 2020;32(8):2635–2655. doi:10.1108/IJCHM-01-2020-0001

23. Edmondson AC, Verdin PJ. The Strategic Imperative of Psychological Safety and Organizational Error Management. In: Hagen J, editor. How Could This Happen? Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. 2018. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-76403-05

24. Wang X, Guchait P, Paşamehmetoğlu A. Why should errors be tolerated? Perceived organizational support, organization-based self-esteem and psychological well-being. J Contemp Hosp Manag. 2020;32(5):1987–2006. doi:10.1108/IJCHM-10-2019-0869

25. van Dyck C, Frese M, Baer M, Sonnentag S. Organizational error management culture and its impact on performance: a two-study replication. J Appl Psychol. 2005;90(6):1228–1240. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1228

26. Frese M, Keith N. Action errors, error management, and learning in organizations. Annu Rev Psychol. 2015;66:661–687. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015205

27. Weinzimmer LG, Esken CA. Learning from mistakes: how mistake tolerance positively affects organizational learning and performance. J Appl Behav Sci. 2017;53(3):322–348. doi:10.1177/0021886316688658

28. Demircioglu MA, Hameduddin T, Knox C. Innovative work behaviors and networking across government. Int Rev Admin Sci. 2023;89(1):145–164. doi:10.1177/00208523211017654

29. Jang E. Sustainable workplace: impact of authentic leadership on change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior and the moderating role of perceived employees’ calling. Sustainability. 2021;13(15):8542. doi:10.3390/su13158542

30. Yuan H, Li Y, Zheng J. The impact of inclusive leadership on employees’ innovative behaviors in Chinese Internet technology companies: the mediating role of error management climate and self-efficacy. Korean Acad Leadersh. 2022;13(2):39–65. doi:10.22243/tklq.2022.13.2.39

31. Younas A, Wang D, Javed B, Zaffar MA. Moving beyond the mechanistic structures: the role of inclusive leadership in developing change-oriented organizational citizenship behaviour. Can J Adm Sci. 2021;38(1):42–52. doi:10.1002/cjas.1586

32. Iqbal Z, Ghazanfar F, Hameed F, Mujtaba G, Swati MA. Ambidextrous leadership and change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior: mediating role of psychological safety. J Public Aff. 2022;22(1). doi:10.1002/pa.2279

33. Blau PM. Exchange and Power in Social Life. Prentice Hall; 1964.

34. Thomas KW, Velthouse BA. Cognitive elements of empowerment: an “interpretive” model of intrinsic Task Motivation. AMR. 1990;15(4):666–681. doi:10.5465/amr.1990.4310926

35. Pradhan RK, Panda M, Jena LK. Transformational leadership and psychological empowerment: the mediating effect of organizational culture in Indian retail industry. J Enterpr Inf Manag. 2017;30(1):82–95. doi:10.1108/JEIM-01-2016-0026

36. Maan AT, Abid G, Butt TH, Ashfaq F, Ahmed S. Perceived organizational support and job satisfaction: a moderated mediation model of proactive personality and psychological empowerment. Future Bus J. 2020;6(1). doi:10.1186/s43093-020-00027-8

37. Younas A, Wang D, Javed B, Haque AU. Inclusive leadership and voice behavior: the role of psychological empowerment. J Soc Psychol. 2022;1–17. doi:10.1080/00224545.2022.2026283

38. Spreitzer GM. Psychological, empowerment in the workplace: dimensions, measurement and validation. Acad Manag J. 1995;38(5):1442–1465. doi:10.2307/256865

39. Monje-Amor A, Xanthopoulou D, Calvo N, Abeal Vázquez JP. Structural empowerment, psychological empowerment, and work engagement: a cross-country study. Eur Manag J. 2021;39(6):779–789. doi:10.1016/j.emj.2021.01.005

40. Ginsburg L, Berta W, Baumbusch J, et al. Measuring work engagement, psychological empowerment, and organizational citizenship behavior among health care aides. Gerontologist. 2016;56(2):e1–e11. doi:10.1093/geront/gnv129

41. Khusanova R, Choi SB, Kang S-W. Sustainable workplace: the moderating role of office design on the relationship between psychological empowerment and organizational citizenship behaviour in Uzbekistan. Sustainability. 2019;11(24):7024. doi:10.3390/su11247024

42. Javed B, Abdullah I, Haque AU, Rubab U. Inclusive leadership and innovative work behavior: the role of psychological empowerment. Acad Manag Proc. 2018;2018(1):15780. doi:10.5465/AMBPP.2018.15780abstract

43. Juyumaya J. How psychological empowerment impacts task performance: the mediating role of work engagement and moderating role of age. Front Psychol. 2022;13:889936. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.889936

44. Perry JL, Wise LR. The motivational bases of public service. Public Admin Rev. 1990;50(3):367. doi:10.2307/976618

45. Vandenabeele W. Toward a public administration theory of public service motivation: an institutional approach. Public Manag Rev. 2007;9(4):545–556. doi:10.1080/14719030701726697

46. Perry JL. Measuring public service motivation: an assessment of construct reliability and validity. J Public Admin Res Theor. 1996;6(1):5–22. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024303

47. Wang TM, van Witteloostuijn A, Heine F. A moral theory of Public Service Motivation. Front Psychol. 2020;11:517763. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.517763

48. Breaugh J, Ritz A, Alfes K. Work motivation and public service motivation: disentangling varieties of motivation and job satisfaction. Public Manag Rev. 2018;20(10):1423–1443. doi:10.1080/14719037.2017.1400580

49. Bright L. Does perceptions of organizational prestige mediate the relationship between public service motivation, job satisfaction, and the turnover intentions of federal employees? Public Pers Manag. 2021;50(3):408–429. doi:10.1177/0091026020952818

50. Molines M, Mifsud M, El Akremi A, Perrier A. Motivated to serve: a regulatory perspective on public service motivation and organizational citizenship behavior. Public Admin Rev. 2022;82(1):102–116. doi:10.1111/puar.13445

51. Nguyen NTH, Nguyen D, Vo N, Tuan LT. Fostering public sector employees’ innovative behavior: the roles of servant leadership, public service motivation, and learning goal orientation. Admin Soc. 2023;55(1):30–63. doi:10.1177/00953997221100623

52. Wright BE, Pandey SK. Public service motivation and the assumption of person-organization fit: testing the mediating effect of value congruence. Admin Soc. 2008;40(5):502–521. doi:10.1177/0095399708320187

53. Houston DJ, Cartwright KE. Spirituality and public service. Public Admin Rev. 2007;67(1):88–102. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00699.x

54. Perry JL, Hondeghem A, Wise LR. Revisiting the motivational bases of public service: twenty years of research and an agenda for the future. Public Admin Rev. 2010;70(5):681–690. doi:10.1111/.2010.0

55. Ryan RM, Deci EL. From ego depletion to vitality: theory and findings concerning the facilitation of energy available to the self. Soc Pers Psychol Compass. 2008;2(2):702–717. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00098.x

56. Van Loon N, Kjeldsen AM, Andersen LB, Vandenabeele W, Leisink P. Only when the societal impact potential is high? A panel study of the relationship between public service motivation and perceived performance. Rev Public Pers Admin. 2018;38(2):139–166. doi:10.1177/0734371X16639111

57. Montani F, Courcy F, Battistelli A, de Witte H. Job insecurity and innovative work behaviour: a moderated mediation model of intrinsic motivation and trait mindfulness. Stress Health. 2021;37(4):742–754. doi:10.1002/smi.3034

58. Heinemann LV, Heinemann T. Burnout research: emergence and scientific investigation of a contested diagnosis. SAGE Open. 2017;7(1). doi:10.1177/2158244017697154

59. Qin X, Ren R, Zhang Z-X, Johnson RE. Considering self-interests and symbolism together: how instrumental and value-expressive motives interact to influence supervisors’ justice behavior. Pers Psychol. 2018;71(2):225–253. doi:10.1111/peps.12253

60. Horvath D, Keith N, Klamar A, Frese M. How to induce an error management climate: experimental evidence from newly formed teams. J Bus Psychol. 2023;38(4):763–775. doi:10.1007/s10869-022-09835-x

61. Brislin RW. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J Cross Cult Psychol. 1970;1(3):185–216. doi:10.1177/135910457000100301

62. Li CP, Shi K. The effects of distributive and procedural fairness on job burnout. J Psychol. 2003;05:677–684.

63. Vigoda-Gadot E, Beeri I. Change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior in public administration: the power of leadership and the cost of organizational politics. J Public Admin Res Theor. 2012;22(3):573–596. doi:10.1093/jopart/mur036

64. Wright BE, Christensen RK, Pandey SK. Measuring public service motivation: exploring the equivalence of existing global measures. Int Public Manag J. 2013;16(2):197–223. doi:10.1080/10967494.2013.817242

65. Shin Y, Kim M, Lee S-H. Positive group affective tone and team creative performance and change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior: a moderated mediation model. J Creat Behav. 2019;53(1):52–68. doi:10.1002/jocb.166

66. Aggarwal A, Lim WM, Jaisinghani D, Nobi K. Driving service-oriented organizational citizenship behavior through error management culture. Serv Ind J. 2022;1–40. doi:10.1080/02642069.2022.2147160

67. Jung HS, Yoon HH. Error management culture and turnover intent among food and beverage employees in deluxe hotels: the mediating effect of job satisfaction. Serv Bus. 2017;11(4):785–802. doi:10.1007/s11628-016-0330-5

68. Li M, Liu W, Han Y, Zhang P. Linking empowering leadership and change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior: the role of thriving at work and autonomy orientation. J Organ Change Manag. 2016;29(5):732–750. doi:10.1108/JOCM-02-2015-0032

69. Yao S, Wang X, Yu H, Guchait P. Effectiveness of error management training in the hospitality industry: impact on perceived fairness and service recovery performance. Int J Hosp Manag. 2019;79:78–88. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.12.009

70. Guchait P, Lee C, Wang C-Y, Abbott JL. Impact of error management practices on service recovery performance and helping behaviors in the hospitality industry: the mediating effects of psychological safety and learning behaviors. J Hum Resour Hosp Tourism. 2016;15(1):1–28. doi:10.1080/15332845.2015.1008395

71. Li Y, Tuckey MR, Bakker A, Chen PY, Dollard MF. Linking objective and subjective job demands and resources in the JD-R model: a multilevel design. Work Stress. 2022;1–28. doi:10.1080/02678373.2022.2028319

72. De Spiegelaere S, Van Gyes G, Van Hootegem G. Not all autonomy is the same. different dimensions of job autonomy and their relation to work engagement and innovative work behavior: not all autonomy is the same. Hum Factors Man. 2016;26(4):515–527. doi:10.1002/hfm.20666

73. Prysmakova P. Contact with citizens and job satisfaction: expanding person-environment models of public service motivation. Public Manag Rev. 2021;23(9):1339–1358. doi:10.1080/14719037.2020.1751252

74. Wright B Toward understanding task, mission and public service motivation: a conceptual and empirical synthesis of goal theory. In:

75. Potipiroon W, Ford MT. Does public service motivation always lead to organizational commitment? Examining the moderating roles of intrinsic motivation and ethical leadership. Public Pers Manag. 2017;46(3):211–238. doi:10.1177/0091026017717241

76. Giauque D, Ritz A, Varone F, Anderfuhren-Biget S. Resigned but satisfied: the negative impact of public service motivation and red tape on work satisfaction. Public Admin. 2012;90(1):175–193. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9299.2011.01953.x

77. Bakker AB. A job demands-resources approach to public service motivation. Public Admin Rev. 2015;75(5):723–732. doi:10.1111/puar.12388

78. Pooja AA, De Clercq D, Belausteguigoitia I. Job stressors and organizational citizenship behavior: the roles of organizational commitment and social interaction: job stressors and organizational citizenship behavior. Hum Resour Dev Q. 2016;27(3):373–405. doi:10.1002/hrdq.21258

79. Guchait P, Paşamehmetoğlu A, Dawson M. Perceived supervisor and co-worker support for error management: impact on perceived psychological safety and service recovery performance. Int J Hosp Manag. 2014;41:28–37. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2014.04.009

80. García-Juan B, Escrig-Tena AB, Roca-Puig V. Psychological empowerment: antecedents from goal orientation and consequences in public sector employees. Rev Public Pers Admin. 2020;40(2):297–326. doi:10.1177/0734371X18814590

81. Schermuly CC, Creon L, Gerlach P, Graßmann C, Koch J. Leadership styles and psychological empowerment: a meta-analysis. J Leadersh Organ Stud. 2022;29:73–95. doi:10.1177/15480518211067751

82. Han S, Liu D, Lv Y. The influence of psychological safety on students’ creativity in project-based learning: the mediating role of psychological empowerment. Front Psychol. 2022;13:865123. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.865123

83. Mussagulova A. Predictors of work engagement: drawing on job demands-resources theory and public service motivation. Aust J Public Admin. 2021;80(2):217–238. doi:10.1111/1467-8500.12449

84. Crucke S, Kluijtmans T, Meyfroodt K, Desmidt S. How does organizational sustainability foster public service motivation and job satisfaction? The mediating role of organizational support and societal impact potential. Public Manag Rev. 2022;24(8):1155–1181. doi:10.1080/14719037.2021.1893801

85. Camilleri E. Towards developing an organisational commitment – public service motivation model for the Maltese public service employees. Public Policy Admin. 2006;21(1):63–83. doi:10.1177/095207670602100105

86. Lapworth L, James P, Wylie N. Examining public service motivation in the voluntary sector: implications for public management. Public Manag Rev. 2018;20(11):1663–1682. doi:10.1080/14719037.2017.1417466

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.