Back to Journals » Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment » Volume 11

Optimal management of night eating syndrome: challenges and solutions

Authors Kucukgoncu S, Midura M, Tek C

Received 26 January 2015

Accepted for publication 21 February 2015

Published 19 March 2015 Volume 2015:11 Pages 751—760

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S70312

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Roger Pinder

Suat Kucukgoncu, Margaretta Midura, Cenk Tek

Department of Psychiatry, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA

Abstract: Night Eating Syndrome (NES) is a unique disorder characterized by a delayed pattern of food intake in which recurrent episodes of nocturnal eating and/or excessive food consumption occur after the evening meal. NES is a clinically important disorder due to its relationship to obesity, its association with other psychiatric disorders, and problems concerning sleep. However, NES often goes unrecognized by both health professionals and patients. The lack of knowledge regarding NES in clinical settings may lead to inadequate diagnoses and inappropriate treatment approaches. Therefore, the proper diagnosis of NES is the most important issue when identifying NES and providing treatment for this disorder. Clinical assessment tools such as the Night Eating Questionnaire may help health professionals working with populations vulnerable to NES. Although NES treatment studies are still in their infancy, antidepressant treatments and psychological therapies can be used for optimal management of patients with NES. Other treatment options such as melatonergic medications, light therapy, and the anticonvulsant topiramate also hold promise as future treatment options. The purpose of this review is to provide a summary of NES, including its diagnosis, comorbidities, and treatment approaches. Possible challenges addressing patients with NES and management options are also discussed.

Keywords: night eating, obesity, psychiatric disorders, weight, depression

Introduction

Stunkard et al1 first discussed Night Eating Syndrome (NES) in 1955, describing it as morning anorexia that is characterized by breakfast skipping, evening hyperphagia, and/or insomnia. NES is characterized by a delayed pattern of food intake in which the patient consumes at least 25% of his or her total daily calories after dinner and/or during nocturnal awakenings.2

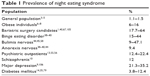

The prevalence of NES is estimated to be 1.1%–1.5% in the general population3–5 and 6%–16% in obese individuals (Table 1).6–8 NES is also associated with several psychiatric disorders and sleep problems.9–14 Despite the growing literature, NES often goes unrecognized in clinical settings, and management options are still in their infancy. The purpose of this review is to provide a summary of NES, including its diagnosis, comorbidities, and treatment approaches. Possible challenges of this unique disorder and management options are discussed.

| Table 1 Prevalence of night eating syndrome |

Diagnosis and assessment of NES

Over the past two decades, NES has been researched in various populations and under various definitions.4,13,15–19 Lack of a standardized definition of NES has impeded recognition of the syndrome, and made it difficult to compare studies done on the disorder.20 Recently, in 2010, diagnostic criteria for NES were proposed to address this limitation.21 NES was also listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition (DSM-V).22 Diagnostic criteria for NES include: 1) recurrent episodes of night eating, as manifested by eating after awakening from sleep or by excessive food consumption following the evening meal, 2) awareness of those eating episodes, and 3) significant distress or impairment caused by the disorder. Exclusion criteria are binge-eating disorder or another mental disorder, as well as medical disorders or medication that might better explain the disordered eating pattern.22

NES is not yet widely recognized by medical professionals.23,24 NES shares some features with other psychiatric disorders, particularly with eating disorders and sleep disorders such as sleep related eating disorders (SRED). However, there are some important differences between NES and these disorders. Therefore, proper diagnosis of NES was suggested as the most important issue when identifying NES and providing optimal management for patients with NES.25 The lack of knowledge of NES in clinical settings may lead to lack of recognition of the syndrome and inappropriate treatment approaches. In order to increase awareness and recognition of NES, Stunkard and Allison26 suggest information campaigns.

Self-report questionnaires and semistructured diagnostic tools including Night Eating Questionnaire (NEQ), Night Eating Syndrome Questionnaire (NESQ), Night Eating Diagnostic Questionnaire (NEDQ), Night Eating Symptom Scale (NESS), Eating Disorder Examination (EDE), and Night Eating Syndrome History and Inventory (NESHI) can be used for the assessment of NES.27 The NEQ is widely used and is a well-recognized self-assessment measure for NES screening.28 The NEQ consists of 14 questions concerning morning anorexia, nocturnal ingestions, evening hyperphagia, mood, and sleep. The positive predictive value (PPV) of a score of 25 or greater is reported as 40.7%; the PPV of a score of 30 or greater is reported as 72.7%. The negative predictive value was high for cut scores of both 25 (95.2%) and 30 (94.0%).28 The NEQ has been adapted to other languages including German,24 Spanish,29 Hebrew,30 Arabic,31 and Turkish.32 The NEQ is also ideal for assessing symptom changes that may occur over the course of NES treatment.

Due to the high number of false positive rates associated with using the NEQ in special populations (such as in obese individuals and gastric bypass patients), use of additional interview tools to diagnose NES has been suggested.20 The NESHI is a semistructured interview, which also includes the NEQ in interview format. The NESHI includes questions about the history of NES symptoms, the amount of food eaten per day, sleep patterns, mood symptoms, life stressors, weight and diet history, and previous treatment of NES.20,33 Food and sleep records, dietary recalls, actigraphy, and polysomnography can also be used to document further information about eating and sleeping patterns.27 Health professionals working with vulnerable populations, such as obese individuals and psychiatric patients, should be encouraged to use NES assessment tools.

Night eating syndrome and eating disorders

NES is more common in patients with other eating disorders (ED), particularly in those with binge-eating disorder (BED) and bulimia nervosa (BN), than in the general population. Furthermore, individuals with NES are also more likely to have other EDs. The estimated prevalence of NES among patients with EDs ranges from 5% to 44%.8,34,35

Extensive research has been conducted to evaluate the relationship between NES and BED.8,21,36–38 NES has been reported to exist in 15%–44% of patients with BED.38–40 Previous studies reported that individuals with NES and BED experience more impairment on psychopathology, weight, and eating habits than individuals with NES or BED alone do.8,34,40,41 There are, however, few studies that have investigated the relationship between NES and anorexia nervosa or BN.42–45 The prevalence of NES was estimated to be 9%–47% in patients with BN.44,45 Therefore, it is important to evaluate NES in patients with abnormal eating habits or other EDs.

High comorbidity rates and various degrees of symptom overlap between NES and other EDs have started a debate regarding the conceptualization of NES. Some researchers conceptualized NES as a subtype of other EDs, whereas others classified NES as a distinct disorder among EDs.46 Despite similarities, NES can be differentiated from other EDs by eating pattern, calories consumed during day, absence of compensatory behavior, and impaired sleep.20 For instance, NES has a time pattern (nightly) whereas BED does not. Moreover, the food intake during binge episodes is greater than the amount of food consumed in NES.25

Overall, studies show that NES and other EDs have affected a large number of people. Therefore, the distinctions between these disorders and consequent treatments are needed. It is also suggested to use assessment tools, such as the NEQ, for basic evaluation of all patients with EDs. Further research is required to identify the clinical significance of symptom overlap between NES and EDs. Finally, patients with both NES and other EDs may also require more intensive treatment approaches. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) may be an effective treatment approach among patients with NES and other EDs. To our knowledge, the only CBT study was a case series of five patients with NES and BED. In this study, the CBT approach improved sleep habits, level of psychopathology, and weight.46,47 Future clinical trials are essential for this challenging population.

Night eating syndrome and psychiatric disorders

Research in patients with NES has also shown association between the syndrome and various psychopathologies, particularly depression.37,48–51 In brief, patients with NES were shown to be more likely to meet lifetime criteria for major depressive disorders,52 anxiety disorders,52 and substance abuse.52,53 Cross-sectional studies showed that patients with NES have higher depressive and anxiety symptoms than non-NES individuals do.7,9,54 On the other hand, relatively less research has been conducted in patients with psychiatric disorders investigating NES. The estimated prevalence of NES in psychiatry patients was reported higher than in the general population: 12.4%–22.4% in psychiatric outpatients,13,55,56 25% in overweight patients with serious mental illness,12 12% in obese patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders,10 and 21.3% in patients with depression.9

Psychiatric symptoms may also increase NES symptoms and complicate the management of NES. Given the link between NES and psychiatric disorders, it is important to identify psychiatric symptoms in patients with NES, and refer them to a psychiatrist if needed. In mental health settings, patients with psychiatric disorders who also have NES may be unaware of NES and not seek treatment.57 Therefore, mental health professionals should be aware of the risk for NES in their patients. Screening and assessment tools for NES may help professionals identify these patients. For instance, individuals who meet criteria for major depressive disorder and complain about abnormal eating behaviors should be evaluated for NES. To our knowledge, no treatment study has been conducted for the treatment of NES in psychiatric disorders. Clinicians should consider individualized treatment options such as SSRI medications, CBT, relaxation exercises, and lifestyle interventions.

Night eating syndrome and sleep

NES may cause and/or trigger sleep disturbances. Likewise, insomnia and sleep disturbances may precede NES. Existing literature shows that patients with NES experience difficulties initiating and maintaining sleep. NES has also been associated with low sleep efficiency.6,9,10,58,59 Possible moderators of sleep problems in patients with NES are disrupted sleep from nocturnal eating episodes and insomnia. NES patients with sleep problems respond to standard treatments of NES, particularly SSRIs. It should be noted that attempts to treat sleep problems with hypnotic medications may produce a confusional state during which NES symptoms may also occur.25

Sleep problems are also common among individuals with psychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety, and schizophrenia. Recent literature suggests that the link between NES and sleep continues to emerge,60 and primary sleep difficulties should thus be an important focus of clinical attention in psychiatric patients with NES.9,10 In addition to evaluating eating patterns, it is recommended to take into consideration the presence of primary sleep difficulties among patients with NES. Besides utilizing treatment options such as SSRIs and CBT, establishing sleep hygine may also improve sleep problems in patients with NES.

Although nocturnal eating episodes are an important feature of NES, these episodes are not solely occurring in NES. Sleep related eating disorder (SRED) is characterized as recurrent episodes of involuntary eating and drinking during sleep, and is considered as parasomnia rather than an eating disorder.61 Like NES, SRED is associated with other sleep problems, depression, eating disorders, and obesity.42,61,62 Furthermore, both disorders have a chronic course and may run in families. Despite these similarities, SRED can be differentiated from NES by the unawareness of nocturnal eating episodes, higher comorbidity with other sleep disorders such as sleepwalking and restless legs syndrome, and the association with sedative hypnotic medications such as zolpidem and triazolam. Unusual consumption of inedible foods and/or substances is also seen in patients with SRED, whereas the most common food choices in NES are breads, sandwiches, and sweets.61,62 Different treatments are suggested for NES and SRED. NES is treated with SSRIs whereas SRED is treated with benzodiazapines, mood stabilizers (eg, topiramate), or dopaminergic medications. Finally, it should be noted that some patients with nocturnal eating problems might be unable to differentiate between NES and SRED.63 Therefore, a thorough sleep history is essential to differentiate NES from SRED. Complete medication and substance use history are required to rule out secondary causes of unawareness during nocturnal eating episodes.64 Further sleep analysis such as polysomnography or videopolysomnography may be helpful in especially complicated cases.

Night eating disorders and obesity

Since NES was first described, studies have reported inconsistent findings regarding the relationship between NES and obesity. Some epidemiological3,65 and cross-sectional studies that were mainly conducted in obese or psychiatric populations reported no connection between NES and obesity.6,7,40,56,67 Conversely, there are studies that showed a positive relationship between NES and obesity.5,9,34,67 Longitudinal studies showed significant weight gain among night eaters, which supports the argument that NES may be a risk factor for obesity development in the future.68,69 There is also evidence that the relationship between NES and obesity is moderated by some demographical factors such as age and sex.20,50,68,70 Contradictory findings may be due to the use of varied diagnostic criteria for evaluating NES, narrow body mass index (BMI) ranges within homogeneous populations, and small sample sizes. Nonetheless, although some previous studies supported the relationship between NES and obesity, the nature of the relationship still remains unclear.71 Therefore, future studies are needed to augment our understanding about the possible relationship between NES and obesity.

Another main concern of NES is its impact on weight loss management. Given the relationship between NES, sleep problems, and depressive symptoms, patients with NES may have difficulties managing weight loss. In fact, NES was first described among individuals with unsuccessful weight loss management.1 Limited research has produced inconsistent results on the influence of NES on weight loss management.7,54,72,73 Research performed on bariatric surgery patients showed no association between NES and weight loss.72,73 Conversely, research conducted with overweight individuals entering a weight loss program showed that NES impaired weight loss management among obese individuals.7 In this study, it is reported that patients with NES struggle with caloric restriction in the context of weight loss.7 It should be noted that these samples also included high rates of BED comorbidity. BED comorbidity might also lead to challenges in weight loss management among patients with NES. Recently, it has been shown that higher emotional eating behaviors moderate the relationship between NES, BED, and body mass index. It is suggested that the differences in emotion regulation between the individuals with NES might lead to an inconsistent result.74

Available data from cross-sectional and longitudinal studies provide an unclear picture of the effects of NES on weight loss management. Recent behavioral and clinical trials showed that the treatment of NES symptoms leads to significant weight loss in patients with NES.75–78 These findings suggest the presence of deleterious effects of NES on weight loss management. Therefore, it is important to address NES symptoms in weight loss approaches.

Night eating syndrome and diabetes

There are few studies that have examined the relationship between NES and diabetes mellitus (DM). Depending on the applied diagnostic criteria for NES and on the study samples, NES was estimated to exist in among 3.8%–12.4% of patients with DM.14,35,79 Previous studies provided mixed results on the relationship between NES and glycemic control among patients with DM. There is some evidence that night eating was associated with poorer diet control, poorer glucose monitoring, and obesity in individuals with DM.80 Some studies showed higher HbA1C levels in patients with NES and DM than in those with only DM,79,80 whereas others found no difference in HbA1C levels between these groups.35 These mixed results do not allow any conclusions to be drawn about the relationship between NES and DM. More study is clearly required regarding the influence of NES in DM management.

Treatment of night eating syndrome

As awareness of NES has grown, research has focused on treatment options for NES. Although treatment studies of NES are still in their early stages, various treatment approaches have been applied to NES, including pharmacologic treatment, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), light therapy, and muscle relaxation strategies (Table 2).30,47,51,75–78,81–89 These studies aimed to improve NES symptoms, especially evening hyperphagia and nocturnal eating episodes, but also mood symptoms and weight loss.

Pharmaceutical treatment of NES

Previous studies suggested that the serotonin system, with its role in appetite, food intake, and circadian rhythms,90,91 might have an active role in the pathophysiology of NES.51,78,92 Lundgren et al93 reported higher levels of serotonin transporter in the temporal lobe of the midbrain in night eaters. Elevations in serotonin transporter levels have been shown to lead to dysfunctions in postsynaptic serotonin transmission.91 These dysfunctions may impair satiety and circadian rhythms, thus leading to NES.94

Based on the relationship between NES and the serotonin system, clinical trials mainly focused on antidepressant medications, particularly SSRIs, in the treatment of NES. One case series81,84 reported improvements in night eating symptoms with paroxetine, and fluvoxamine treatments. Effects of sertraline and escitalopram on NES have been tested in two double blind randomized (DBR) placebo-controlled77,88 and three open label clinical trials.51,75,78 Uncontrolled studies with sertraline showed that the treatment improved NES symptoms, mood symptoms, and quality of life in patients with NES. Both, caloric intake after the evening and weight reduced with sertraline treatment in these studies.51,78 Similar to the uncontrolled studies, in an 8-week DBR clinical trial,77 sertraline treatment significantly improved NES symptoms and quality of life and decreased caloric intake after the evening meal when compared to placebo. There were two clinical trials conducted with escitalopram.75,88 In a 12-week DBR placebo-controlled study of escitalopram conducted with 31 patients with NES, improvements in night eating symptoms were reported. Patients on escitalopram had also lost a modest 0.43±0.7 kg at week 12. However, these improvements were not significant between the drug and placebo groups.88 A lack of significant findings between the placebo and escitalopram groups may be partly attributed to differential response rates by race88 and the small sample size.75 Recently, an open label escitalopram study reported significant improvements in NES symptoms and depressive symptoms in patients with NES.75 Although mean weight loss was around 2 kg in the whole sample, 13 out of 31 patients gained more than 0.9 kg during the study. Even though we have a limited theoretical basis for using SSRI medications for NES, at this point, these findings suggest that sertraline and escitalopram can be used as first-line treatment approaches for NES. Future randomized controlled studies using other SSRIs and selective noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors are essential.

Previous studies showed that patients with NES experience attenuation of the nocturnal rise in plasma melatonin levels.48 Although this finding was not replicated later,92 two case studies reported the beneficial effects of agomelatine, a selective melatonin agonist, on NES and depressive symptoms without the presence of adverse side effects.86,87 Agomelatine is also a weak serotonin 5-HT2C receptor antagonist. While its melatonin agonism is considered to normalize the sleep–wake cycle, synergistic effects of melatonin agonism and serotonin antagonism are believed to reduce depressive and anxious symptoms.95,96 This dual action mechanism was suggested to improve NES by reducing nocturnal eating episodes, and also by improving sleep problems and depressive symptoms.86,87 Considering the low side effect profiles, melatonin and other melatonin agonists such as agomelatine and ramelteon can be options for NES treatment. Future controlled trials with melatonin agonists are required.

Three case reports have shown the beneficial effects of topiramate, a GABA agonist and glutamatergic antagonist, in treatment of NES.30,85,97 In these case reports, it was shown that adding topiramate treatment to ongoing treatments improved NES symptoms and led to significant weight loss. However, after dose reduction or treatment discontinuation, NES symptoms had returned in these patients. The mechanism of action by which topiramate is beneficial for night eating is unclear, but it was attributed to the well-known anorexigenic effect of topiramate.97 Topiramate has prominent side effects such as cognitive impairment and kidney stones, and thus should be used with caution.

Collectively, limited pharmaceutical studies suggested that SSRI medications, (particularly sertraline and escitalopram), melatonergic medications, and topiramate may be effective for the treatment of NES. Finally, to date there are no guidelines or data on the duration of the therapeutic benefit of medications on NES.98 It is recommended that a medication treatment be used for no fewer than 8 weeks before determining if it is either successful or unsuccessful in treating NES. If effective, the medication should be continued for at least a year before trying to phase it out over the course of 2–3 months.99

Psychological interventions for NES

Besides pharmacological treatments, psychological interventions have also been applied in NES treatment.47,76,89 In a randomized controlled trial, it is reported that 1-week abbreviated progressive muscle relaxation training (PMR) decreased self-reported levels of state anxiety, perceived stress, evening appetite, and morning anorexia. Recently, Vander Wal et al100 have tested the effectiveness of PMR, education, and exercise therapy for the treatment of NES. In this randomized study, all three interventions (educational, educational + PMR, PMR + exercise) reduced the symptoms of NES. These findings suggest that PMR may be beneficial in the treatment of NES.89,100

CBT has been demonstrated as an effective treatment for many psychiatric disorders, including depression, eating disorders, and insomnia. Anecdotal notes and experiments in patients with NES revealed that NES is associated with some cognitive distortions such as believing one is unable to sleep unless eating beforehand, specific food cravings, and feeling anxious or agitated.101–103 Recently, Allison et al76,101 introduced a cognitive behavioral treatment by adapting the CBT protocols for BED and behavioral weight loss.25 Core components of CBT can be summarized as follow: 1) psychoeducation about NES and healthy eating, 2) eating modification, 3) relaxation strategies, 4) establishing sleep hygiene, 5) cognitive restructuring, 6) improving physical activity, and 7) establishing social support.20 The primary aim of CBT in the context of NES is to correct the delay in circadian eating rhythms, while simultaneously interrupting the relationship between erroneous cognitions and night eating and sleep.25

Recently, clinical outcomes of CBT for NES have been reported.47,76 In a preliminary study, five patients with NES and BED received 10 sessions of CBT and 2 sessions of sleep related intervention.47 Three out of the five patients finished the CBT sessions in this study. Preliminary results indicated improvements in sleep habits, level of psychopathology, and weight. Thus far, only one uncontrolled CBT trial has been conducted in patients with NES.76 In this trial, 14 out of 25 patients received 10 hours of CBT sessions over 12 weeks. CBT treatment produced significant reductions in evening hyperphagia, number of nocturnal eating episodes, total caloric intake, and depressive symptoms. Interestingly, CBT reduced the amount of eating most significantly during nocturnal ingestions, but not during the period after dinner. This finding suggests that CBT treatment for NES may be more effective in reducing nocturnal ingestions than evening hyperphagia.104 Overall, CBT for NES appears to be a promising treatment. However, it should be noted that previous CBT studies were conducted with small sample sizes. There is need for future randomized controlled trials with larger samples. Comparison studies of CBT with other treatment strategies are needed, and the effectiveness of combining pharmaceutical treatments with CBT should also be tested in future studies. Although the aforementioned CBT treatments showed improvements in mood symptoms, the effect of psychiatric comorbidities on CBT outcome is unknown in patients with NES. Therefore, studies of the impact of comorbidity on treatment response may be necessary. Given the complexity of diagnosis and accompanying mood and sleep problems, treatment of NES should be individualized to the patient.

Conclusion

NES is a unique disorder that has complex associations with obesity, psychiatric disorders, endocrine and metabolic disturbances, and sleep problems. Recognizing NES and identifying comorbid conditions is important in providing relevant treatments, and thus preventing the deleterious effects of this disorder in the long-term. It is suggested that health professionals working with high-risk individuals, such as individuals with eating concerns, obesity, depressive symptoms, or sleep problems, apply screening tools for NES in clinical settings. Pharmaceutical treatment options (eg, SSRIs, melatonergic medications) and/or psychological interventions (eg, CBT, behavioral interventions, relaxation exercises) can be considered as treatment options for NES. Finally, further research is essential to elucidate the assessment, conceptualization, comorbidities and, most importantly, the treatment for NES.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by grant number 1R01 DK093924 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIHDDK) at the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Stunkard AJ, Grace WJ, Wolff HG. The night-eating syndrome; a pattern of food intake among certain obese patients. Am J Med. 1955;19(1):78–86. | ||

O’Reardon JP, Ringel BL, Dinges DF, et al. Circadian eating and sleeping patterns in the night eating syndrome. Obes Res. 2004;12(11):1789–1796. | ||

Rand CS, Macgregor AM, Stunkard AJ. The night eating syndrome in the general population and among postoperative obesity surgery patients. Int J Eat Disord. 1997;22(1):65–69. | ||

Striegel-Moore RH, Dohm FA, Hook JM, Schreiber GB, Crawford PB, Daniels SR. Night eating syndrome in young adult women: prevalence and correlates. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;37(3):200–206. | ||

de Zwaan M, Muller A, Allison KC, Brahler E, Hilbert A. Prevalence and correlates of night eating in the German general population. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e97667. | ||

Ceru-Bjork C, Andersson I, Rossner S. Night eating and nocturnal eating-two different or similar syndromes among obese patients? Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25(3):365–372. | ||

Gluck ME, Geliebter A, Satov T. Night eating syndrome is associated with depression, low self-esteem, reduced daytime hunger, and less weight loss in obese outpatients. Obes Res. 2001;9(4):264–267. | ||

Stunkard A, Berkowitz R, Wadden T, Tanrikut C, Reiss E, Young L. Binge eating disorder and the night-eating syndrome. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1996;20(1):1–6. | ||

Kucukgoncu S, Tek C, Bestepe E, Musket C, Guloksuz S. Clinical features of night eating syndrome among depressed patients. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2014;22(2):102–108. | ||

Palmese LB, Ratliff JC, Reutenauer EL, Tonizzo KM, Grilo CM, Tek C. Prevalence of night eating in obese individuals with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2013;54(3):276–281. | ||

Gallant AR, Lundgren J, Drapeau V. The night-eating syndrome and obesity. Obes Rev. 2012;13(6):528–536. | ||

Lundgren JD, Rempfer MV, Brown CE, Goetz J, Hamera E. The prevalence of night eating syndrome and binge eating disorder among overweight and obese individuals with serious mental illness. Psychiatry Res. 2010;175(3):233–236. | ||

Lundgren JD, Allison KC, Crow S, et al. Prevalence of the night eating syndrome in a psychiatric population. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):156–158. | ||

Hood MM, Reutrakul S, Crowley SJ. Night eating in patients with type 2 diabetes. Associations with glycemic control, eating patterns, sleep, and mood. Appetite. 2014;79:91–96. | ||

Allison KC, Wadden TA, Sarwer DB, et al. Night eating syndrome and binge eating disorder among persons seeking bariatric surgery: prevalence and related features. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2006;2(2):153–158. | ||

Goel N, Stunkard AJ, Rogers NL, et al. Circadian rhythm profiles in women with night eating syndrome. J Biol Rhythms. 2009;24(1):85–94. | ||

Marshall HM, Allison KC, O’Reardon JP, Birketvedt G, Stunkard AJ. Night eating syndrome among nonobese persons. Int J Eat Disord. 2004;35(2):217–222. | ||

Striegel-Moore RH, Franko DL, Thompson D, Affenito S, Kraemer HC. Night eating: prevalence and demographic correlates. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006;14(1):139–147. | ||

Striegel-Moore RH, Thompson D, Franko DL, et al. Definitions of night eating in adolescent girls. Obes Res. 2004;12(8):1311–1321. | ||

Vander Wal JS. Night eating syndrome: a critical review of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012;32(1):49–59. | ||

Allison KC, Lundgren JD, O’Reardon JP, et al. Proposed diagnostic criteria for night eating syndrome. Int J Eat Disord. 2010;43(3):241–247. | ||

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. | ||

Goncalves MD, Moore RH, Stunkard AJ, Allison KC. The treatment of night eating: the patient’s perspective. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2009;17(3):184–190. | ||

Meule A, Allison KC, Platte P. A German version of the Night Eating Questionnaire (NEQ): psychometric properties and correlates in a student sample. Eat Behav. 2014;15(4):523–527. | ||

Allison KC, Tarves EP. Treatment of night eating syndrome. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2011;34(4):785–796. | ||

Stunkard A, Allison K. Treatment of the Night Eating Syndrome. In: Preedy VR, Watson RR, Martin C, editors. Handbook of Behavior, Food and Nutrition. New York, NY: Springer; 2011. | ||

Lundgren J. The night eating syndrome: an overview In: Preedy VR, Watson RR, Martin C, editors. Handbook of Behavior, Food and Nutrition. New York, NY: Springer; 2011. | ||

Allison KC, Lundgren JD, O’Reardon JP, et al. The Night Eating Questionnaire (NEQ): psychometric properties of a measure of severity of the Night Eating Syndrome. Eat Behav. 2008;9(1):62–72. | ||

Moize V, Gluck ME, Torres F, Andreu A, Vidal J, Allison K. Transcultural adaptation of the Night Eating Questionnaire (NEQ) for its use in the Spanish population. Eat Behav. 2012;13(3):260–263. | ||

Cooper-Kazaz R. Treatment of night eating syndrome with topiramate: dawn of a new day. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32(1):143–145. | ||

Hamid MS, Allison KC. Psychometric characteristics of the Night Eating Questionnaire in a Middle East population. Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47(6):660–665. | ||

Atasoy N, Saracli O, Konuk N, et al. The reliability and validity of Turkish version of the Night Eating Questionnaire in psychiatric outpatient population. J Anatolian Psychiatry. 2014;15(3):238–247. | ||

Lundgren JD, Allison KC, Vinai P, Gluck ME. Assessment instruments for night eating syndrome. In: Lundgren JD, Allison KC, Stunkard AJ, editors. Night Eating Syndrome: Research, Assessment, and Treatment. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2012. | ||

Colles SL, Dixon JB, O’Brien PE. Night eating syndrome and nocturnal snacking: association with obesity, binge eating and psychological distress. Int J Obes (Lond). 2007;31(11):1722–1730. | ||

Allison KC, Crow SJ, Reeves RR, et al. Binge eating disorder and night eating syndrome in adults with type 2 diabetes. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007;15(5):1287–1293. | ||

Adami GF, Meneghelli A, Scopinaro N. Night eating and binge eating disorder in obese patients. Int J Eat Disord. 1999;25(3):335–338. | ||

Allison KC, Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Stunkard AJ. Binge eating disorder and night eating syndrome: a comparative study of disordered eating. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(6):1107–1115. | ||

Greeno CG, Wing RR, Marcus MD. Nocturnal eating in binge eating disorder and matched-weight controls. Int J Eat Disord. 1995;18(4):343–349. | ||

Grilo CM, Masheb RM. Night-time eating in men and women with binge eating disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2004;42(4):397–407. | ||

Napolitano MA, Head S, Babyak MA, Blumenthal JA. Binge eating disorder and night eating syndrome: psychological and behavioral characteristics. Int J Eat Disord. 2001;30(2):193–203. | ||

Allison KC, Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Stunkard AJ. High self-reported rates of neglect and emotional abuse, by persons with binge eating disorder and night eating syndrome. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(12):2874–2883. | ||

Winkelman JW. Sleep-related eating disorder and night eating syndrome: sleep disorders, eating disorders, or both? Sleep. 2006;29(7):876–877. | ||

Lundgren JD, Shapiro JR, Bulik CM. Night eating patterns of patients with bulimia nervosa: a preliminary report. Eat Weight Disord. 2008;13(4):171–175. | ||

Lundgren JD, McCune A, Spresser C, Harkins P, Zolton L, Mandal K. Night eating patterns of individuals with eating disorders: implications for conceptualizing the night eating syndrome. Psychiatry Res. 2010;186(1):103–108. | ||

Tzischinsky O, Latzer Y. Nocturnal eating: prevalence, features and night sleep among binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa patients in Israel. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2004;12(2):101–109. | ||

Latzer Y, Tzischinski O. Night eating syndrome research, assessment, and treatment. In: Lundgren JD, Allison KC, Stunkard AJ, editors. Night Eating Syndrome Research, Assessment, and Treatment. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2012. | ||

Edelstein R, Rabin O, Hason M, Givon M, Alon S, Kabakov O. CBT for patients with BED and NES. Paper presented at: Israeli Annual Conference for ATID Nutrition Association; 2010; Bar Ilan University, Israel. | ||

Birketvedt GS, Florholmen J, Sundsfjord J, et al. Behavioral and neuroendocrine characteristics of the night-eating syndrome. JAMA. 1999;282(7):657–663. | ||

Calugi S, Dalle GR, Marchesini G. Night eating syndrome in class II–III obesity: metabolic and psychopathological features. Int J Obes (Lond). 2009;33(8):899–904. | ||

Gluck ME, Venti CA, Salbe AD, Votruba SB, Krakoff J. Higher 24-h respiratory quotient and higher spontaneous physical activity in night- time eaters. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2011;19(2):319–323. | ||

O’Reardon JP, Stunkard AJ, Allison KC. Clinical trial of sertra- line in the treatment of night eating syndrome. Int J Eat Disord. 2004;35(1):16–26. | ||

Lundgren JD, Allison KC, O’Reardon JP, Stunkard AJ. A descriptive study of non-obese persons with night eating syndrome and a weight- matched comparison group. Eat Behav. 2008;9(3):343–351. | ||

Striegel-Moore RH, Franko DL, Thompson D, Affenito S, May A, Kraemer HC. Exploring the typology of night eating syndrome. Int J Eat Disord. 2008;41(5):411–418. | ||

Dalle GR, Calugi S, Ruocco A, Marchesini G. Night eating syn- drome and weight loss outcome in obese patients. Int J Eat Disord. 2011;44(2):150–156. | ||

Saracli O, Atasoy N, Akdemir A, et al. The prevalence and clinical features of the night eating syndrome in psychiatric out-patient popula- tion. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;57:79–84. | ||

Kucukgoncu S, Bestepe E. Night eating syndrome in major depression and anxiety disorders. Arch Neuropsychiatry. 2014;51(4):368–375. | ||

Rempfer MV, Murphy ME. Night eating syndrome and other psychiatric disorders. In: Lundgren JD, Allison KC, Stunkard AJ, editors. Night Eating Syndrome Research, Assessment, and Treatment. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2012. | ||

Winkelman JW. Clinical and polysomnographic features of sleep-related eating disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(1):14–19. | ||

Rogers NL, Dinges DF, Allison KC, et al. Assessment of sleep in women with night eating syndrome. Sleep. 2006;29(6):814–819. | ||

Howell MJ, Crow SJ. Nocturnaleatingandsleepdisorders.In:Lundgren JD, Allison KC, Stunkard AJ, editors. Night Eating Syndrome Research, Assessment, and Treatment. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2012. | ||

American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders. 3rd Ed. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014. | ||

Howell MJ, Schenck CH. Treatment of nocturnal eating disorders. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2009;11(5):333–339. | ||

Vetrugno R, Manconi M, Ferini-Strambi L, Provini F, Plazzi G, Montagna P. Nocturnal eating: sleep-related eating disorder or night eating syndrome? A videopolysomnographic study. Sleep. 2006;29(7):949–954. | ||

Auger RR. Sleep-related eating disorders. Psychiatry. 2006;3(11): 64–70. | ||

Striegel-Moore RH, Franko DL, May A, Ach E, Thompson D, Hook JM. Should night eating syndrome be included in the DSM? Int J Eat Disord. 2006;39(7):544–549. | ||

Adami GF, Campostano A, Marinari GM, Ravera G, Scopinaro N. Night eating in obesity: a descriptive study. Nutrition. 2002;18(7–8): 587–589. | ||

Aronoff NJ, Geliebter A, Zammit G. Gender and body mass index as related to the night-eating syndrome in obese outpatients. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001;101(1):102–104. | ||

Andersen GS, Stunkard AJ, Sorensen TI, Petersen L, Heitmann BL. Night eating and weight change in middle-aged men and women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28(10):1338–1343. | ||

Gluck ME, Venti CA, Salbe AD, Krakoff J. Nighttime eating: com- monly observed and related to weight gain in an inpatient food intake study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(4):900–905. | ||

Meule A, Allison KC, Brahler E, de Zwaan M. The association between night eating and body mass depends on age. Eat Behav. 2014; 15(4):683–685. | ||

Colles SL, Dixon JB. The relationship of night eating syndrome with obe- sity, bariatric surgery, and physical health. In: Lundgren JD, Allison KC, Stunkard AJ, editors. Night Eating Syndrome Research, Assessment, and Treatment. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2012. | ||

Powers PS, Perez A, Boyd F, Rosemurgy A. Eating pathology before and after bariatric surgery: a prospective study. Int J Eat Disord. 1999;25(3):293–300. | ||

Colles SL, Dixon JB, O’Brien PE. Grazing and loss of control related to eating: two high-risk factors following bariatric surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008;16(3):615–622. | ||

Meule A, Allison KC, Platte P. Emotional eating moderates the relation- ship of night eating with binge eating and body mass. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2014;22(2):147–151. | ||

Allison KC, Studt SK, Berkowitz RI, et al. An open-label efficacy trial of escitalopram for night eating syndrome. Eat Behav. 2013; 14(2):199–203. | ||

Allison KC, Lundgren JD, Moore RH, O’Reardon JP, Stunkard AJ. Cognitive behavior therapy for night eating syndrome: a pilot study. Am J Psychother. 2010;64(1):91–106. | ||

O’Reardon JP, Allison KC, Martino NS, Lundgren JD, Heo M, Stunkard AJ. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of sertraline in the treatment of night eating syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(5): 893–898. | ||

Stunkard AJ, Allison KC, Lundgren JD, et al. A paradigm for facilitating pharmacotherapy at a distance: sertraline treatment of the night eating syndrome. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(10):1568–1572. | ||

Schwandt B, de Zwaan M, Jager B. Co-morbidity between type 2 dia- betes mellitus and night eating. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2012;62(12):463–468. | ||

Morse SA, Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Hirsch IB. Isn’t this just bed- time snacking? The potential adverse effects of night-eating symptoms on treatment adherence and outcomes in patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(8):1800–1804. | ||

Spaggiari MC, Granella F, Parrino L, Marchesi C, Melli I, Terzano MG. Nocturnal eating syndrome in adults. Sleep. 1994;17(4):339–344. | ||

Friedman S, Even C, Dardennes R, Guelfi JD. Light therapy, obesity, and night-eating syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(5):875–876. | ||

Friedman S, Even C, Dardennes R, Guelfi JD. Light therapy, non- seasonal depression, and night eating syndrome. Can J Psychiatry. 2004;49(11):790. | ||

Miyaoka T, Yasukawa R, Tsubouchi K, et al. Successful treatment of nocturnal eating/drinking syndrome with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;18(3):175–177. | ||

Tucker P, Masters B, Nawar O. Topiramate in the treatment of comorbid night eating syndrome and PTSD: a case study. Eat Disord. 2004;12(1):75–78. | ||

Milano W, De Rosa M, Milano L, Capasso A. Agomelatine efficacy in the night eating syndrome. Case Rep Med. 2013;2013:867650. | ||

Milano W, De Rosa M, Milano L, Riccio A, Sanseverino B, Capasso A. Successful treatment with agomelatine in NES: a series of five cases. Open Neurol J. 2013;7:32–37. | ||

Vander Wal JS, Gang CH, Griffing GT, Gadde KM. Escitalopram for treatment of night eating syndrome: a 12-week, randomized, placebo- controlled trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32(3):341–345. | ||

Pawlow LA, O’Neil PM, Malcolm RJ. Night eating syndrome: effects of brief relaxation training on stress, mood, hunger, and eating patterns. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27(8):970–978. | ||

Clifton PG, Kennett GA. Monoamine receptors in the regulation of feed- ing behaviour and energy balance. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2006;5(3):293–312. | ||

Frazer A. Pharmacology of antidepressants. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1997;17(Suppl 1):2S–18S. | ||

Allison KC, Ahima RS, O’Reardon JP, et al. Neuroendocrine profiles associated with energy intake, sleep, and stress in the night eating syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(11):6214–6217. | ||

Lundgren JD, Newberg AB, Allison KC, Wintering NA, Ploessl K, Stunkard AJ. 123I-ADAM SPECT imaging of serotonin transporter binding in patients with night eating syndrome: a preliminary report. Psychiatry Res. 2008;162(3):214–220. | ||

Stunkard AJ, Allison KC, Lundgren JD, O’Reardon JP. A biobehav- ioural model of the night eating syndrome. Obes Rev. 2009;10(Suppl 2): 69–77. | ||

de Bodinat C, Guardiola-Lemaitre B, Mocaer E, Renard P, Munoz C, Millan MJ. Agomelatine, the first melatonergic antidepressant: dis- covery, characterization and development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9(8):628–642. | ||

Laudon M, Frydman-Marom A. Therapeutic effects of melatonin receptor agonists on sleep and comorbid disorders. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15(9):15924–15950. | ||

Winkelman JW. Treatment of nocturnal eating syndrome and sleep-related eating disorder with topiramate. Sleep Med. 2003;4(3):243–246. | ||

Patel KR, O’Reardon JP, Cristancho MA. Pharmacological treatment of night eating syndrome. In: Lundgren JD, Allison KC, Stunkard AJ, editors. Night Eating Syndrome Research, Assessment, and Treatment. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2012. | ||

O’Reardon JP, Peshek A, Allison KC. Night eating syndrome: diagnosis, epidemiology and management. CNS Drugs. 2005;19(12):997–1008. | ||

Vander Wal JS, Maraldo TM, Vercellone AC, Gagne DA. Education, progressive muscle relaxation therapy, and exercise for the treatment of night eating syndrome. A pilot study. Appetite. Epub February 4, 2015. | ||

Allison KC. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Manuel for Night Eating Syndrome. In: Lundgren JD, Allison KC, Stunkard AJ, eds. Night Eating Syndrome Research, Assessment, and Treatment. New York: The Guilford Press; 2012. | ||

Vinai P, Allison KC, Cardetti S, et al. Psychopathology and treatment of night eating syndrome: a review. Eat Weight Disord. 2008;13(2):54–63. | ||

Vinai P, Cardetti S, Studt S, et al. Clinical validity of the descriptor. “Presence of a belief that one must eat in order to get to sleep” in diagnosing the Night Eating Syndrome. Appetite. 2014;75:46–48. | ||

Allison KC. Cognitive-behavioral therapy and night eating syndrome. In: Lundgren JD, Allison KC, Stunkard AJ, editors. Night Eating Syndrome Research, Assessment, and Treatment. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2012. | ||

Mitchell JE, King WC, Courcoulas A, et al. Eating behavior and eating disorders in adults before bariatric surgery. Int J Eat Disord. 2015;48(2):215–222. | ||

Orhan FO, Ozer UG, Ozer A, Altunoren O, Celik M, Karaaslan MF. Night eating syndrome among patients with depression. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2011;48(3):212–217. |

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.