Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 15

Negative Influences of Differentiated Empowering Leadership on Team Members’ Helping Behaviors: The Mediating Effects of Envy and Contempt

Authors Sun F, Li X, Akhtar MN

Received 3 November 2021

Accepted for publication 21 December 2021

Published 6 January 2022 Volume 2022:15 Pages 9—20

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S346470

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Mei-Chun Cheung

Fang Sun,1 Xiyuan Li,1 Muhammad Naseer Akhtar2

1Economics and Management School, Wuhan University, Wuhan, People’s Republic of China; 2Royal Docks School of Business and Law, The University of East London, London, UK

Correspondence: Xiyuan Li

Economics and Management School, Wuhan University, Wuhan, 430072, People’s Republic of China

Tel +86-27-68752551

Email [email protected]

Purpose: Given the popularity of empowerment practices among scholars and practitioners, this research examines whether a manager’s differentiated empowering leadership negatively affects team members’ helping behaviors and, if so, how.

Methods: The authors conducted one multi-source and time-lagged survey (with 44 managers and 212 team members) and two scenario-based experiments (with 120 participants in Study 2 and 121 participants in Study 3) to test the research model.

Results: Team managers’ differentiated empowering leadership decreases team members’ helping behaviors. In particular, for team members who receive less empowerment, differentiated empowering leadership may decrease their helping behaviors by eliciting their envy. For team members who receive more empowerment, differentiated empowering leadership may decrease their helping behaviors by inducing their contempt.

Conclusion: This research introduces the concept of differentiated empowering leadership in response to calls to investigate the dark side of empowering leadership. It reveals that unequal distribution of authority among team members by managers can undermine employee relations and elicit negative emotions of envy and contempt, thereby decreasing employees’ helping behaviors.

Keywords: differentiated empowering leadership, envy, contempt, helping behavior

Introduction

With increasingly fierce competition in the external business world,1 managers cannot quickly or effectively cope with the management challenge by relying only on their own knowledge, skills, and experience. Accordingly, there is a growing awareness that managers should increase their companies’ effectiveness and flexibility by empowering their subordinates.2 In their leadership development programs, companies such as Google, Microsoft, and LinkedIn have long trained their managers on empowerment. Given this trend among practitioners, organizational behavior and organizational psychology researchers are paying greater attention to the empowering behaviors of managers (ie, empowering leadership) and have conducted dozens of studies in this area.2

Empowering leadership is defined as managers’ behaviors in fostering employee autonomy, authority, and self-responsibilities. As this research stream progresses, a group of influential scholars have found two main gaps that require further research. First, researchers should further consider the dark side of empowering leadership.2,3 To date, the majority of studies have focused on the positive effects of empowering leadership. For instance, research has found that managers’ empowering behaviors can increase employee performance,4 as well as extra-role behaviors.5 However, increasing evidence suggests that empowering leadership is not always beneficial in workplace contexts.6,7 Hence, Cheong et al (2019) have called for closer examination of whether and how managers’ empowering behaviors might cause outcomes that are less positive or even negative.2

Second, research on the configural properties of empowering leadership should be carried out in the team context.8 Given the popularity of team-oriented work structure in the workplace,9 the growing but still limited body of research on empowering leadership in that context has focused exclusively on the influence of shared empowering leadership on employee attitudes and behaviors.2 In a team, shared empowering leadership involves the team manager treating team members equally and granting each of them a similar degree of autonomy, authority, and support.10 However, a manager is more likely to empower different team members differently than to empower without distinction.11 Research in connection with variation in managers’ empowering behaviors toward different team members is beginning to emerge, but remains insufficient. In theory building and empirical studies, scholars of organizational psychology are seeking to complement research based on the perspective of shared team properties (reflecting experiences, attitudes, perceptions, or behaviors that are held in common by all team members, ie, shared empowering leadership) with an emphasis on configural team properties (reflecting the array, pattern, or variability of individual experiences, cognitions, and behaviors within a team, ie, differentiated empowering leadership).12 Accordingly, to obtain a more thorough understanding of the impact of empowering leadership, we should examine the effects of differentiated empowering leadership.

We find that team members’ helping behaviors are important outcomes that may be affected by managers’ differentiated empowering leadership. Helping behaviors among team members contribute to the maintenance of good interpersonal relationships, which are beneficial for team operation and effectiveness.13 Recently, researchers have started to explore the effects of shared empowering leadership on helping behavior.10 However, our knowledge of this relationship is far from complete, and further studies are required.10 One way to advance our understanding of the relationship is to investigate whether and how differentiated empowering leadership, which is different from shared empowering leadership in that it is based on the perspective of configural team properties, can affect helping behaviors. Specifically, drawing on social comparison theory and the literature regarding envy and contempt, we propose that the underlying mechanism that links differentiated empowering leadership and team members’ helping behaviors is negative emotion (in particular, envy and contempt). Managers can affect employees’ behaviors by influencing their emotions.14,15 Variation in a team manager’s empowerment toward different team members can induce intense feelings of emotion, affecting team members’ intention to help others. In summary, we seek to address the issues mentioned above by exploring the following research questions:

RQ1. Can differentiated empowering leadership by team managers negatively influence team members’ helping behaviors?

RQ2. Are emotions (ie, envy and contempt) the underlying mediating mechanisms that link differentiated empowering leadership and team members’ helping behaviors?

Our findings contribute to research on empowering leadership and will be of value to practitioners using empowerment. First, this study contributes to the literature on the unintended influences of empowering leadership by exploring whether and how managers’ differentiated empowering leadership can decrease team members’ helping behaviors. Thus, a better and more thorough understanding of the impact of empowering leadership is obtained. Second, this study enriches the research on the underlying mechanism of the effects of empowering leadership by clarifying the mediating roles of negative emotions (here, envy and contempt) in linking differentiated empowering leadership and team members’ helping behaviors. Third, this study clarifies how empowering leadership works within a team by using the configural team property perspective to construct an idea of differentiated empowering leadership. Last, the findings of this study provide insights for managers on how to empower their members in the team context.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. The second section delineates the rationale we used to develop our hypotheses. The third section presents the empirical testing of our hypotheses. The fourth section draws conclusions from the research findings, discusses their theoretical and practical implications, and notes their limitations. Figure 1 illustrates our overall research model.

|

Figure 1 Proposed research model. Notes: A solid arrow indicates a direct relationship, and dotted arrows indicate indirect relationships. |

Theory and Hypotheses

Differentiated Empowering Leadership and Social Comparison Theory

Before we frame our hypotheses, it is necessary to define differentiated empowering leadership. In line with previous research,8,16,17 we define it as the extent to which a team manager exhibits varying levels of empowering behaviors toward team members. Differentiated empowering leadership is high when managers distribute power, autonomy, and authority unequally among their team members. In contrast, differentiated empowering leadership is low when managers empower their team members in an identical and equal way. According to leader–member exchange theory, a team manager can develop differentiated exchange relationships (high vs low quality) with each team member by giving varying amounts of authority and support.18

Social comparison theory suggests that people have an innate motivation to draw comparisons with similar others in order to evaluate themselves or reduce uncertainty.19 Depending on the target of comparison, social comparison can be classified as upward20 or downward.21 Upward social comparison is comparison with those considered to be superior on a given characteristic, whereas downward social comparison is comparison with those considered to be inferior on a specific characteristic.20,21 If a team manager distributes authority, such as decision-making and work autonomy, among team members in a highly unequal way (ie, creates a situation with highly differentiated empowering leadership), each member’s status within the team may be differentiated. Some team members will receive abundant empowerment, while the others will receive little empowerment. Team members with more empowerment then become the insiders of the team manager and are in a superior position within the team.8 Team members with less empowerment are considered the outsiders of the team manager and hold inferior positions in the team.8

Direct Effect of Differentiated Empowering Leadership on Helping Behavior

We propose that managers’ differentiated empowering leadership has a negative direct effect on team members’ helping behaviors for two reasons. First, according to social comparison theory, individuals tend to define themselves through comparison with other individuals. Team members who receive more empowerment can be considered (or self-classified) as insiders of their team manager. In contrast, team members with less empowerment can be considered (or self-classified) as outsiders. This faultline created by the team manager’s high degree of differentiated empowerment can cause tension between team members.22 Prior research has indicated that leader–member exchange (LMX) differentiation, which is similar to differentiated empowering leadership, can induce conflict between insiders and outsiders.23 Second, balance theory proposes that the contrasting quality of relationships between different manager–member dyads can cause a deterioration in member–member relationships.24 Chiniara and Bentein (2018) found that LMX differentiation can have a negative effect on team cohesion.25 As team members’ relationships become estranged, they may refuse to help each other.

Although no prior empirical research has investigated the relationship between differentiated empowering leadership and helping behaviors, studies on similar concepts provide evidence that supports our argument. For example, despotic leaders, who have a great degree of authority, may be more likely to empower each team member differently. Zhou et al (2021) found that despotic leadership negatively affects employees’ job satisfaction, and employees who are not satisfied with their jobs are less likely to help their colleagues.26 Chen and Zhang (2021) noted that LMX relational separation can reduce employees’ intentions to carry out altruistic behaviors such as helping.27 Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Team managers’ differentiated empowering leadership has a negative effect on team members’ helping behaviors.

We next seek to clarify the underlying mechanisms for this phenomenon. Integrating social comparison theory with the concepts of envy and contempt, we speculate that differentiated empowering leadership can induce nuanced and different negative emotions among team members according to the extent of the empowerment they receive from their team managers. Specifically, differentiated empowering leadership can elicit feelings of envy on the part of team members who receive less empowerment. In contrast, differentiated empowering leadership can induce contempt among team members who receive more empowerment. With the combination of these mechanisms, both emotions, envy and contempt, can reduce the intention of each team member to help the others. We articulate these two mediation mechanisms in the following sections.

The Mediating Role of Envy Among Team Members with Less Empowerment

Drawing on social comparison theory and the literature on envy, we argue that, among team members with less empowerment, envy can mediate the relationship between managers’ differentiated empowering leadership and team members’ helping behaviors. Envy is a typical emotional reaction elicited by social comparison, especially upward social comparison with a superior target in a domain that one values.28 The occurrence of envy depends on the following two conditions: First, two persons are similar or close to each other; Second, one person has something that the other person values but does not have.29 On this basis, we argue that team members who have less empowerment are likely to experience envy resulting from upward social comparison with team members who have more empowerment. As part of a team, members interact frequently and should be considered nominally equal in status; hence, they are similar and comparable. Moreover, in the workplace, the authority that is distributed by team managers is something that all of the team members care about and is often used as a basis for comparison.

Thus, team members with less empowerment may envy those who have more opportunities for participative decision-making and greater work autonomy. Team members with less empowerment are likely to have feelings of envy because of the substantial gap in authority and status compared to others in the team who have high degrees of differentiated empowering leadership. Pelled (1996) observed that group members may experience unpleasant feelings because of the social comparison process.30 More directly, Lee (2001) argued that subordinates who have poor exchange relationships with their supervisors will be jealous of colleagues who have good exchange relationships with their supervisors.31 Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2a: For team members with less empowerment, differentiated empowering leadership is positively associated with their emotion of envy.

We further argue that team members who are envious may further suppress their intention to help others. Envy is a painful feeling of emotion.32 Cohen-Charash and Muller (2007) suggested that people who experience envy tend to ease their emotion by narrowing the gap between themselves and the person they envy.29 Scholars have pointed out that one way to equalize status is to hurt the envied person through counterproductive work behaviors,32 or by undermining them.33 However, engaging in malicious harm is highly risky and may be punished formally (eg, with a low performance rating) or informally (eg, through shunning or retaliation) by the organization and its managers.34 As a result, an envious team member may be more inclined to choose a way to equalize status that their organization and managers will not easily detect. One such way is refusing to help those who are envied.

In a team context, there is a high level of task interdependency among team members.35 If an envious team member chooses not to help a team member he/she envies, this may lead to poor performance from both parties. Nevertheless, the envious member may succeed in decreasing the envy-provoking advantage that the envied team member has, and this will help to ease the experience of envy. In this connection, empirical research indicates that envy can inhibit the helping behaviors of employees. For example, Kim et al (2010) found that employees with strong feeling of envy decreased their organizational citizenship behaviors.36 Sun et al (2021) found that envious employees were less likely to help the coworkers they envied.37 Hence, we predict that envy has a negative effect on team members’ helping behaviors: the stronger the feeling of envy, the fewer helping behaviors they will conduct. Integrating these considerations with Hypotheses 1 and 2a, we propose the following indirect effect hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2b: For team members with less empowerment, envy mediates the negative effects of differentiated empowering leadership on helping behaviors.

The Mediating Role of Contempt Among Team Members with More Empowerment

Drawing on social comparison theory, we propose that team members who have more empowerment are inclined to experience emotions of contempt resulting from downward social comparison with team members who have less empowerment. Contempt is an emotional experience that implies disdain for and social exclusion of another person or group.38 It is a typical emotional reaction after downward social comparison.39 As team members with less empowerment have less authority, such as decision-making or work autonomy, they are considered the outsiders of the team managers. Drawing on the dynamic social model of contempt, team members who have more empowerment may experience a sense of superiority, leading them to despise team members who have less empowerment.40

Accordingly, the large gap in power and status caused by a high degree of differentiated empowering leadership is likely to induce emotions of contempt among members with more empowerment toward those with less empowerment. Sias and Jablin (1995) argued that high-status members disrespect low-status members in groups with high levels of LMX variability,41 and Tse et al (2013) found empirical support for this argument.42 Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3a: For team members with more empowerment, differentiated empowering leadership is positively associated with their emotion of contempt.

We argue that team members who experience feelings of contempt may suppress their intention to help their disrespected colleagues for the following reasons. First, once an individual has formed feelings of contempt toward someone else, they will try to distance themselves from that person or even exclude them from their social network.40 Although task interdependence makes it impossible for team members to isolate someone else within the team completely, the emotion of contempt can motivate them to reduce interpersonal interaction with the target of the contempt.38 Consequently, for team members who have more empowerment, the emotion of contempt may reduce their interpersonal interactions with and intention to assist team members who have less empowerment.

Second, research on the motivational effect of helping behaviors has demonstrated that gaining the favor of receivers of help and building good interpersonal relationships are two essential motivators.43 Thus, because of their emotion of contempt, team members who have more empowerment have less motivation to help team members who have less empowerment. Hence, we speculate that contempt is negatively related to team members’ helping behaviors: the stronger the feeling of contempt, the less helping behavior they will conduct. Schriber et al (2017) argued that individuals with dispositional contempt tend to be cold.44 More directly, Tse et al (2013) found that employees who experience feelings of contempt were less likely to help their colleagues.42 Integrating these considerations with Hypotheses 1 and Hypothesis 3a, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3b: For team members with more empowerment, contempt mediates the negative effects of differentiated empowering leadership on helping behaviors.

Research Approach

We employed one field survey and two scenario experiments. In Study 1, a field survey with a multi-source and time-lagged design, we examined the main effect of team managers’ differentiated empowering leadership on team members’ helping behaviors (testing Hypothesis 1). Field survey is a method used extensively in organizational psychology and management research, and it has high external validity.45 However, Study 1 did not test the underlying mediating mechanisms directly, and its design does not permit causal conclusions to be drawn. To address these limitations, we conducted two scenario-based experiments, a method that has high internal validity and can be used to test causal conclusions. Specifically, in Studies 2 and 3, we manipulated differentiated empowering leadership to explore its indirect effects on team members’ helping behaviors by increasing the less empowered team members’ emotion of envy (testing Hypotheses 2a and 2b) or by increasing the more empowered team members’ emotion of contempt (testing Hypotheses 3a and 3b) see Appendix for all of our research instruments.

Study 1

Participants and Design

We collected data from a large beverage chain corporation with stores in many provinces in China (mainly in the eastern region). Each store had an independent team with a team manager (the store manager) and several team members, which met the sample requirements of this study. With the approval of the company’s executive manager, we invited 50 stores at random to participate in our survey. We emphasized the voluntary nature of their participation and guaranteed complete confidentiality to all participants. All surveys were administered electronically using mobile phones, and labeled IDs (eg, Leader 1 for the team manager of Team 1 and member 1–1 for a member of Team 1) were used to match the data.

We invited 262 employees and 50 managers from the 50 stores to complete our survey at Time 1. After two weeks, as some team managers and members did not respond at Time 2, the final sample consisted of 212 team members and 44 team managers from 44 stores. Of the 212 team members, 59.4% were female. Their mean age was 26.65 (SD = 7.38), and their average job tenure was 1.35 years (SD = 1.42). The majority (81.6%) had received senior high school or higher education. Of the 44 team managers, 54.5% were female. Their average age was 29.39 (SD = 5.53), and their average job tenure was 3.82 years (SD = 3.72). All of them had received senior high school or higher education.

Measures

The original English questionnaires were translated into Chinese using back-translation processes.46 Unless otherwise indicated, we used 7-point Likert scales (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) to collect the responses to each item.

Differentiated empowering leadership. Differentiated empowering leadership is a configural team property. In line with Li et al (2015, 2017),8,16 we evaluated it using the coefficient of variance (ie, by dividing the within-team standard deviation of empowering leadership by the mean score of empowering leadership of all the members). This measurement was used by Wu et al (2010) in their study of differentiated transformational leadership.17 The team members rated their team manager’s empowering leadership using six items from Chen and Aryee’s (2007) delegation scale.47 A sample item is “My team manager does not require that I get his/her input or approval before making decisions” (Cronbach’s α = 0.9).

Helping behaviors. Team managers rated team members’ helping behaviors using a 7-item scale developed by Podsakoff et al (1997).48 A sample item is “Help each other out if someone falls behind in his/her work” (Cronbach’s α = 0.89).

Control variables. Previous research has found that an individual’s perception of empowering leadership could affect their helping behaviors.5 We therefore controlled for perceived empowering leadership rated by team members using Chen and Aryee’s (2007) 6-item scale.47 In addition, in line with previous research,16 we included age, gender, job tenure, and education level in the analyses as control variables.

Results

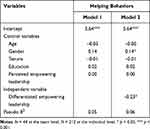

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, and correlations of all the variables. Before the hypothesis testing, we carried out a collinearity test. The results showed that the variance inflation factor (VIF) scores of all the predictors were below 5,49 indicating that collinearity is not an issue in this study. The nested structure of the data and the significant between-team variances in helping behavior (ICC(1) = 0.42) justified the use of hierarchical linear modeling in the analyses.50 To handle missing data in Study 1, we used the mean imputation method. To facilitate the interpretation of the results, we grand-mean centered all the variables at the team level and group-mean centered all the variables at the individual level (with the exception of gender, a dummy variable).51 Table 2 presents the findings of our analyses. The results for Model 2 suggest that differentiated empowering leadership had a negative effect on team members’ helping behaviors (β = –0.23, p < 0.05), which supports Hypothesis 1.

|

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics, Reliabilities, and Correlations in Study 1 |

|

Table 2 Hierarchical Linear Modeling Results in Study 1 |

Study 1, a field survey with three-wave manager–member paired data from 212 team members and their 44 team managers, supports our hypothesized main effect that team managers’ differentiated empowering leadership decreases team members’ helping behaviors. However, Study 1 did not directly test the underlying mechanisms for that effect, and its design does not allow causal conclusions to be drawn. To address these limitations, we conducted two scenario-based experiments (Studies 2 and 3).

Study 2

Participants, Procedures, and Measures

The scenario-based experiments of Studies 2 and 3 were implemented via an online survey platform. In Study 2, a total of 130 participants with work experience were recruited via an online advertisement and were rewarded with 10 Chinese yuan (about 1.55 US dollars) for their participation. We employed a two-scenario design, and all participants were assigned at random to one of these two conditions: high versus low levels of differentiated empowering leadership. It is worth emphasizing that all the participants in Study 2 were manipulated as less empowered team members.

Participants read one of the following scenarios, which served as the manipulation of differentiated empowering leadership:

Scenario 1 (high differentiated empowering leadership): Ms. Xu is the manager of your team, who likes to empower her team members. She often invites some specific members to discuss team issues, and they have more opportunities to participate in decision-making. Ms. Xu makes most of your team’s work plans and strategies after consulting those specific members, and the opinions expressed by the remaining team members are not taken seriously. In addition, those specific members have high levels of work autonomy, such as how and when to complete their work. You belong to a group of members with relatively less empowerment.

Scenario 2 (low differentiated empowering leadership): Ms. Xu is the manager of your team, who likes to empower her team members. She often invites all team members to discuss team issues. Although some specific team members have more opportunities to participate in the discussion, all members have decision-making authority to a certain extent. Ms. Xu makes most of your team’s work plans and strategies after consulting all members. Although the opinions of some specific members are more valued, the voices of all members can be heard more or less. In addition, although some members have more rights to determine their own work procedures, all team members have a certain level of work autonomy, such as how and when to complete your work. You belong to a group of members with relatively less empowerment.

Next, we asked the participants to answer the following questions. First, we asked them to evaluate their emotion of envy on a 9-item scale adapted from Cohen-Charash’s (2009) episodic envy scale (sample item: “I have a grudge against team members with more empowerment”; 1 = strongly disagree, 9 = strongly agree; α = 0.87).52 Second, the participants rated their intentions to help using six items that fit more closely with our experiment and were adapted from the classic scale developed by Williams and Anderson (1991) (sample item: “I will help them if those more empowered team members are absent”; 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree; α = 0.9).53 Third, we conducted a manipulation check using one item, “The authority our team manager gives to different members varies greatly” (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). The data for 10 participants were not included in the analyses because their response time was less than 1 minute, which indicated a lack of reliability. As a result, we retained a sample of 120 participants eligible for analysis, with 60 participants in each of the two scenarios.

Results

Manipulation check. t-test results showed that participants’ perceived degree of differentiated empowering leadership in Scenario 1 was significantly higher than in Scenario 2 (M Scenario 1 = 5.30, SD = 1.42; M Scenario 2 = 4.20, SD = 1.85; t (118) = 3.66, p < 0.001). Thus, our manipulations of differentiated empowering leadership were effective.

Hypothesis testing. t-test results showed that the participants in Scenario 1 reported higher feelings of envy than participants in Scenario 2 (High differentiated empowering leadership condition: M Scenario 1 = 5.26, SD = 1.52; Low differentiated empowering leadership condition: M Scenario 2 = 4.08, SD = 1.32; t (118) = 4.56, p < 0.001), which supports Hypothesis 2a. t-test results also showed that the participants in Scenario 1 reported lower intention to help than participants in Scenario 2 (High differentiated empowering leadership condition: M Scenario 1 = 3.77, SD = 1.5; Low differentiated empowering leadership condition: M Scenario 2 = 4.49, SD = 1.04; t (118) = –3.06, p < 0.01), which supports Hypothesis 1.

We transformed the independent variable, namely differentiated empowering leadership, into a dummy variable (1 = high degree of differentiated empowering leadership, 0 = low degree of differentiated empowering leadership). We then used PROCESS software (Hayes, 2018) to test the mediation effect of Hypothesis 2b.54 The results of our analysis indicate that envy played a mediating role in linking differentiated empowering leadership and helping behaviors (indirect effect = –0.24, 95% CI = [–0.55, –0.01]), which supports Hypothesis 2b. In summary, the results of Study 2 indicate that, for team members with less empowerment, differentiated empowering leadership reduced their intention to help team members who have more empowerment, and their emotion of envy mediated this negative effect.

Study 3

Participants, Procedures, and Measures

In a similar vein, in Study 3, we recruited 136 participants and assigned them at random to one of the two scenario experiments. However, all the participants in Study 3 were manipulated as team members with more empowerment. The procedures of Study 3 were similar to those of Study 2. Participants read the scenario for one of the two conditions, which served as the manipulation of differentiated empowering leadership. The two scenarios were almost the same as those used in Study 2, with the exception of the last sentence, which was rewritten as You belong to a group of members with relatively more empowerment.

As in Study 2, we then asked the participants to evaluate their contempt emotion and their intention to help. Participants first rated their emotion of contempt using eight items adapted from the contempt scale developed by Schriber et al (2017) (sample item: “I often feel like that the less empowered team members are wasting my time”; 1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree; α = 0.74).44 Second, participants evaluated their intention to help using the same scale as in Study 2 (sample item: “I will help them if those less empowered team members are absent”; 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree; α = 0.87). Third, we conducted a manipulation check using the same item as we used in Study 2. We excluded 15 participants whose response times were less than 1 minute. As a result, we retained a sample of 121 participants eligible for analysis, with 61 participants in Scenario 1 and 60 in Scenario 2.

Results

Manipulation check. t-test results showed that participants’ perceived degree of differentiated empowering leadership in Scenario 1 was significantly higher than in Scenario 2 (M Scenario 1 = 5.16, SD = 1.5; M Scenario 2 = 4.58, SD = 1.39; t (119) = 2.21, p < 0.05), indicating the effectiveness of our manipulations of differentiated empowering leadership.

Hypothesis testing. t-test results revealed that the participants in Scenario 1 reported higher feelings of contempt than the participants in Scenario 2 (High differentiated empowering leadership condition: M Scenario 1 = 2.52, SD = 0.7; Low differentiated empowering leadership condition: M Scenario 2 = 2.09, SD = 0.55; t (119) = 3.79, p < 0.001), which supports Hypothesis 3a. t-test results also showed that the participants in Scenario 1 reported lower intention to help than participants in Scenario 2 (High differentiated empowering leadership condition: M Scenario 1 = 4.71, SD = 1.2; Low differentiated empowering leadership condition: M Scenario 2 = 5.26, SD = 0.98; t (119) = –2.78, p < 0.01), which further supports Hypothesis 1. We used the same method to test Hypothesis 3b. The results showed that the mediation effect of contempt was significant (indirect effect = –0.16, 95% CI = [–0.41, –0.01]), which supports Hypothesis 3b. In summary, Study 3 showed that, for team members with more empowerment, differentiated empowering leadership reduced their intention to help those less empowered, and their contempt emotion mediated this negative effect.

Discussion

Theoretical Implications

First, this study extends the literature on empowering leadership by adopting a holistic view of leadership.55 The results determine the negative effects of differentiated empowering leadership on helping behaviors, thereby supporting Hypothesis 1 and responding to calls for more attention to the dark side of empowering leadership. Although the majority of research on empowering leadership has focused on its positive outcomes,3 researchers have started to explore its potential non-positive and even negative results to secure a more comprehensive understanding of its influences.7,56 Specifically, drawing on social comparison theory, we demonstrate that differentiated empowering leadership has negative influences on helping behaviors. These results advance our understanding of the overall effects of empowering leadership and contribute to the burgeoning research on the unintended influences of a popular leadership style that is broadly seen as positive (eg, transformational leadership).57 Although there is no prior research on the relationship between differentiated empowering leadership and helping behaviors, studies of similar concepts support our findings. For example, Chen and Zhang (2021) demonstrated that LMX relational separation can be detrimental to the altruistic behaviors of subordinates.27 Similarly, Wang et al (2017) found that LMX differentiation can decrease employees’ organizational citizenship behaviors (such as helping).58

Second, our research demonstrates that for team members with low empowerment, envy is the underlying mechanism that links differentiated empowering leadership and helping behaviors. This finding supports Hypotheses 2a and 2b. Although no prior research has examined this particular mediating relationship, support for our findings can be found in a number of studies. For example, Thompson et al (2018) found that supervisors’ differentiation of subordinates elicits emotions of jealousy,59 while Sun et al (2021) demonstrated that envious employees reduce their helping behaviors toward their coworkers.37 We also confirmed that for team members with high empowerment, contempt mediates the negative effects of differentiated empowering leadership on helping behaviors, which supports Hypotheses 3a and 3b. Again, prior studies provide support for this conclusion. For example, Sias and Jablin (1995) argued that in groups with high levels of LMX variability, high-status members disrespect low-status members,41 while Tse et al (2013) found that employees who experience feelings of contempt reduce their helping behaviors.42 By integrating social comparison theory with the literature on envy and contempt, our research demonstrates that emotional mechanisms are essential in explaining the influence of empowering leadership on employees’ outcomes.

Third, by adopting a configural view, our research answers the call to explore the influences of empowering leadership in the team context.8 With team structure used by a growing number of companies, scholars have begun to examine team-level empowering leadership more closely.16 However, to date, most studies have simply grafted individual-level theories and research paradigms onto team-level research, ignoring the frequent interactions among team members that can impact their perceptions of managers’ empowerment.2,8 Here, however, we capture a more nuanced picture of the interactions between empowering managers and team members by adopting a perspective on configural team properties. Specifically, we offer the new knowledge that the harmful effects of differentiated empowering leadership on team members’ helping behaviors may be due to negative emotions aroused in the interaction processes.

Practical Implications

Team managers can benefit from the insights our research provides into how to empower team members. Managers should be very cautious about the empowerment strategies they employ within the team. Because of the intensity of their interactions, team members know each other very well. The extent of the empowerment of different members is far from a private matter between the manager and the target member; it is an open secret among the team members. The extent of the decision-making authority and work autonomy distributed by team managers is something that all team members care about and is often used as a basis for comparison. Our research suggests that if team managers empower different team members unequally, tensions among team members are likely. Members with less empowerment will envy members with more empowerment, while members with more empowerment will despise members with less empowerment. The accumulation of these negative emotions will split the team and further reduce team members’ helping behaviors. Rasool et al (2021) found that a toxic workplace environment is harmful to employee engagement.60 Harassment and ostracism, which can be induced by team members’ emotions of envy or contempt, are typical characteristics of the toxic workplace environment. Therefore, team managers should empower their members equally and identically.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study has several limitations. First, although we used a time-lagged and multi-source design to minimize common method variance, the cross-sectional design in Study 1 prevents us from making causal inferences. We addressed this limitation by conducting two scenario-based experiments (Studies 2 and 3) that allowed us to draw causal conclusions; we also encourage future research to employ longitudinal designs to validate our model. Second, we used two scenario experiments to examine the mediation effects of envy and contempt. Although the internal validity of our experiment design is good, we encourage future research to increase external validity by using the experienced sampling method. Third, we focused on the direct and indirect effects of differentiated empowering leadership on team members’ helping behaviors. We therefore encourage future research to explore the boundary conditions of our research framework. For example, it has been argued that emotional intelligence is good for social interaction.61 Future research in the team context can therefore explore whether the negative effects of differentiated empowering leadership on members’ helping behaviors is attenuated when managers have a high level of emotional intelligence.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first study drawing on the configural view to explore the negative effects of empowering leadership on helping behaviors. In line with our predictions, the results of a survey and two scenario experiments suggest that differentiated empowering leadership decreases team members’ helping behaviors. Specifically, for team members who receive less empowerment, differentiated empowering leadership can decrease their helping behaviors by increasing their emotion of envy. For team members who receive more empowerment, differentiated empowering leadership can decrease their helping behaviors by increasing their emotion of contempt.

Ethical Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Before commencing the data collection, the study was approved by the Research Project Ethical Review Committee of Social Sciences Faculty at Wuhan University. According to our research design, the study did not violate any legal regulations or standard ethical guidelines. We introduced our research purpose, goals, and plans to each participant and got their consent. Additionally, we emphasized that all the participants could reject any questions or withdraw from the study at any time. Lastly, their anonymity and confidentiality were assured.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Zhou X, Rasool SF, Ma D. The relationship between workplace violence and innovative work behavior: the mediating roles of employee wellbeing. Healthcare. 2020;8(3):332. doi:10.3390/healthcare8030332

2. Cheong M, Yammarino FJ, Dionne SD, Spain SM, Tsai CY. A review of the effectiveness of empowering leadership. Leadersh Q. 2019;30(1):34–58. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.08.005

3. Sharma PN, Kirkman BL. Leveraging leaders: a literature review and future lines of inquiry for empowering leadership research. Group Organ Manage. 2015;40(2):193–237. doi:10.1177/1059601115574906

4. Amundsen S, Martinsen ØL. Empowering leadership: construct clarification, conceptualization, and validation of a new scale. Leadersh Q. 2014;25(3):487–511. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.11.009

5. Raub S, Robert C. Differential effects of empowering leadership on in-role and extra-role employee behaviors: exploring the role of psychological empowerment and power values. Hum Relat. 2010;63(11):1743–1770. doi:10.1177/0018726710365092

6. Hao P, He W, Long L-R. Why and when empowering leadership has different effects on employee work performance: the pivotal roles of passion for work and role breadth self-efficacy. J Leadersh Organ Stud. 2018;25(1):85–100. doi:10.1177/1548051817707517

7. Humborstad SW, Nerstad CGL, Dysvik A. Empowering leadership, employee goal orientations and work performance: a competing hypothesis approach. Pers Rev. 2014;43(2):246–271. doi:10.1108/PR-01-2012-0008

8. Li S-L, Huo Y, Long LR. Chinese traditionality matters: effects of differentiated empowering leadership on followers’ trust in leaders and work outcomes. J Bus Ethics. 2017;145(1):81–93. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2900-1

9. Mathieu J, Maynard MT, Rapp T, Gilson L. Team effectiveness 1997–2007: a review of recent advancements and a glimpse into the future. J Manag. 2008;34(3):410–476. doi:10.1177/0149206308316061

10. Li N, Chiaburu DS, Kirkman BL. Cross-level influences of empowering leadership on citizenship behavior: organizational support climate as a double-edged sword. J Manag. 2017;43(4):1076–1102. doi:10.1177/0149206314546193

11. Mills P, Ungson G. Reassessing the limits of structural empowerment: organizational constitution and trust as controls. Acad Manage Rev. 2003;28(1):143–153. doi:10.2307/30040694

12. Klein KJ, Kozlowski SW. From micro to meso: critical steps in conceptualizing and conducting multilevel research. Organ Res Methods. 2000;3(3):211–236. doi:10.1177/109442810033001

13. Van Der Vegt GS, Bunderson JS, Oosterhof A. Expertness diversity and interpersonal helping in teams: why those who need the most help end up getting the least. Acad Manage J. 2006;49(5):877–893. doi:10.5465/AMJ.2006.22798169

14. Kim M, Beehr TA, Prewett MS. Employee responses to empowering leadership: a meta-analysis. J Leadersh Organ Stud. 2018;25(3):257–276. doi:10.1177/1548051817750538

15. Weiss HM, Cropanzano R. Affective events theory: a theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. In: Staw BM, Cummings LL, editors. Research in Organizational Behavior: An Annual Series of Analytical Essays and Critical Reviews. US: Elsevier Science/JAI Press; 1996:1–74.

16. Li S-L, He W, Yam KC, Long LR. When and why empowering leadership increases followers’ taking charge: a multilevel study in China. Asia Pac J Manag. 2015;32(3):645–670. doi:10.1007/s10490-015-9424-1

17. Wu JB, Tsui AS, Kinicki AJ. Consequences of differentiated leadership in groups. Acad Manage J. 2010;53(1):90–106. doi:10.5465/amj.2010.48037079

18. Liden RC, Erdogan B, Wayne SJ, Sparrowe RT. Leader-member exchange, differentiation, and task interdependence: implications for individual and group performance. J Organ Behav. 2006;27(6):723–746. doi:10.1002/job.409

19. Festinger LA. Theory of social comparison processes. Hum Relat. 1954;7(2):117–140. doi:10.1177/001872675400700202

20. Collins RL. For better or worse: the impact of upward social comparison on self-evaluations. Psychol Bull. 1996;119(1):51–69. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.119.1.51

21. Wills TA. Downward comparison principles in social psychology. Psychol Bull. 1981;90(2):245–271. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.90.2.245

22. Lau DC, Murnighan JK. Demographic diversity and faultlines: the compositional dynamics of organizational groups. Acad Manage Rev. 1998;23(2):325–340. doi:10.2307/259377

23. Li AN, Liao H. How do leader–member exchange quality and differentiation affect performance in teams? An integrated multilevel dual process model. J Appl Psychol. 2014;99(5):847–866. doi:10.1037/a0037233

24. Heider F. The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations. New York: Wiley; 1958.

25. Chiniara M, Bentein K. The servant leadership advantage: when perceiving low differentiation in leader-member relationship quality influences team cohesion, team task performance and service OCB. Leadersh Q. 2018;29(2):333–345. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.05.002

26. Zhou X, Rasool SF, Yang J, Asghar MZ. Exploring the relationship between despotic leadership and job satisfaction: the role of self efficacy and leader–member exchange. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):5307. doi:10.3390/ijerph18105307

27. Chen S, Zhang C. What happens to a black sheep? Exploring how multilevel leader–member exchange differentiation shapes the organizational altruism behaviors of low leader–member exchange minority. Group Organ Manage. 2021;46(6):1073–1105. doi:10.1177/1059601121998584

28. Gilbert DT, Giesler RB, Morris KA. When comparisons arise. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69(2):227–236. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.69.2.227

29. Cohen-Charash Y, Mueller JS. Does perceived unfairness exacerbate or mitigate interpersonal counterproductive work behaviors related to Envy? J Appl Psychol. 2007;92(3):666–680. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.3.666

30. Pelled LH. Demographic diversity, conflict, and work group outcomes: an intervening process theory. Organ Sci. 1996;7:615–631. doi:10.1287/orsc.7.6.615

31. Lee J. Leader-member exchange, perceived organizational justice, and cooperative communication. Manage Commun Q. 2001;14(4):574–589. doi:10.1177/0893318901144002

32. Lieberman MD, Eisenberger NI. Pains and pleasures of social life. Science. 2009;323(5916):890–891. doi:10.1126/science.1170008

33. Duffy MK, Scott KL, Shaw JD, Tepper BJ, Aquino K. A social context model of envy and social undermining. Acad Manage J. 2012;55(3):643–666. doi:10.5465/amj.2009.0804

34. Spector PE, Fox S. The stressor-emotion model of counterproductive work behavior. In: Fox S, Spector PE, editors. Counterproductive Work Behavior: Investigations of Actors and Targets. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 2005:151–174.

35. Kozlowski SWJ, Bell BS. Work groups and teams in organizations. In: Borman WC, Ilgen DR, Klimoski RJ, editors. Handbook of Psychology: Industrial and Organizational Psychology. New York: Wiley-Blackwell; 2003:333–375.

36. Kim S, O’Neill JW, Cho HM. When does an employee not help coworkers? The effect of leader–member exchange on employee envy and organizational citizenship behavior. Int J Hosp Manag. 2010;29(3):530–537. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2009.08.003

37. Sun J, Li W-D, Li Y, Liden RC, Li S, Zhang X. Unintended consequences of being proactive? Linking proactive personality to coworker envy, helping, and undermining, and the moderating role of prosocial motivation. J Appl Psychol. 2021;106(2):250–267. doi:10.1037/apl0000494

38. Fischer AH, Roseman IJ. Beat them or ban them: the characteristics and social functions of anger and contempt. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;93(1):103–115. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.93.1.103

39. Melwani S, Mueller JS, Overbeck JR. Looking down: the influence of contempt and compassion on emergent leadership categorizations. J Appl Psychol. 2012;97(6):1171–1185. doi:10.1037/a0030074

40. Fischer A, Giner-Sorolla R. Contempt: derogating others while keeping calm. Emot Rev. 2016;8(4):346–357. doi:10.1177/1754073915610439

41. Sias PM, Jablin FM. Differential superior–subordinate relations, perceptions of fairness, and coworker communication. Hum Commun Res. 1995;22(5):38. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.1995.tb00360.x

42. Tse HHM, Lam CK, Lawrence SA, Huang X. When my supervisor dislikes you more than me: the effect of dissimilarity in leader–member exchange on coworkers’ interpersonal emotion and perceived help. J Appl Psychol. 2013;98(6):974–988. doi:10.1037/a0033862

43. Spitzmuller M, Van Dyne L. Proactive and reactive helping: contrasting the positive consequences of different forms of helping. J Organ Behav. 2013;34(4):560–580. doi:10.1002/job.1848

44. Schriber RA, Chung JM, Sorensen KS, Robins RW. Dispositional contempt: a first look at the contemptuous person. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2017;113(2):280–309. doi:10.1037/pspp0000101

45. Rasool SF, Samma M, Wang M, Zhao Y, Zhang Y. How human resource management practices translate into sustainable organizational performance: the mediating role of product, process and knowledge innovation. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2019;12:1009–1025. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S204662

46. Brislin RW. Translation and content analysis of oral and written material. In: Triandis HC, Berry JW, editors. Handbook of Cross-Cultural Psychology. Boston: Allyn & Bacon; 1980:389–444.

47. Chen ZX, Aryee S. Delegation and employee work outcomes: an examination of the cultural context of mediating processes in China. Acad Manage J. 2007;50(1):226–238. doi:10.5465/amj.2007.24162389

48. Podsakoff PM, Ahearne M, Mackenzie SB. Organizational citizenship behavior and the quantity and quality of work group performance. J Appl Psychol. 1997;82(2):262–270. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.82.2.262

49. Chatterjee S, Hadi AS, Price B. Regression Analysis by Examples. 3rd Edition. New York: Wiley VCH; 2000.

50. Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001.

51. Hofmann DA, Griffin MA, Gavin MB. The application of hierarchical linear modeling to organizational research. In: Klein KJ, Kozlowski SWJ, editors. Multilevel Theory, Research, and Methods in Organizations: Foundations, Extensions, and New Directions. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2000:467–511.

52. Cohen‐Charash Y. Episodic envy. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2009;39(9):2128–2173. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2009.00519.x

53. Williams LJ, Anderson SE, Satisfaction J. Organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. J Manag. 1991;17(3):601–617. doi:10.1177/014920639101700305

54. Hayes AF. Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: quantification, inference, and interpretation. Commun Monogr. 2018;85(1):4–40. doi:10.1080/03637751.2017.1352100

55. Avolio BJ, Walumbwa FO, Weber TJ. Leadership: current theories, research, and future directions. Annu Rev Psychol. 2009;60(1):421–449. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163621

56. Cheong M, Spain SM, Yammarino FJ, Yun S. Two faces of empowering leadership: enabling and burdening. Leadersh Q. 2016;27(4):602–616. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2016.01.006

57. Anderson MH, Sun PYT. The downside of transformational leadership when encouraging followers to network. Leadersh Q. 2015;26(5):790–801. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2015.05.002

58. Wang L, Wan J, Liu Z, Ma X. Shared leadership and team effectiveness: the examination of LMX differentiation and servant leadership on the emergence and consequences of shared leadership. Hum Perform. 2017;30(4):155–168. doi:10.1080/08959285.2017.1345909

59. Thompson G, Buch R, Glasø L. Follower jealousy at work: a test of Vecchio’s model of antecedents and consequences of jealousy. J Psychol. 2018;152(1):60–74. doi:10.1080/00223980.2017.1407740

60. Rasool SF, Wang M, Tang M, Saeed A, Iqbal J. How toxic workplace environment effects the employee engagement: the mediating role of organizational support and employee wellbeing. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(5):2294. doi:10.3390/ijerph18052294

61. Iqbal J, Qureshi N, Ashraf MA, Rasool SF, Asghar MZ. The effect of emotional intelligence and academic social networking sites on academic performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2021;14:905–920. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S316664

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.