Back to Journals » Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment » Volume 13

Multicenter, open-label, exploratory clinical trial with Rhodiola rosea extract in patients suffering from burnout symptoms

Received 19 August 2016

Accepted for publication 25 November 2016

Published 22 March 2017 Volume 2017:13 Pages 889—898

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S120113

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Roger Pinder

Siegfried Kasper,1 Angelika Dienel2

1Universitätsklinik für Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie, Medizinische Universität Wien, Wien, Austria; 2Dr Willmar Schwabe GmbH & Co. KG, Karlsruhe, Germany

Purpose: This study is the first clinical trial aiming to explore the clinical outcomes in burnout patients treated with Rhodiola rosea. The reported capacity of R. rosea to strengthen the organism against stress and its good tolerability offer a promising approach in the treatment of stress-related burnout. The aim of the treatment was to increase stress resistance, thus addressing the source rather than the symptoms of the syndrome and preventing subsequent diseases associated with a history of burnout. The objective of the trial was to provide the exploratory data required for planning future randomized trials in burnout patients in order to investigate the clinical outcomes of treatment with R. rosea dry extract in this target group.

Methods: The study was planned as an exploratory, open-label, multicenter, single-arm trial. A wide range of rating scales were assessed and evaluated in an exploratory data analysis to generate hypotheses regarding clinical courses and to provide a basis for the planning of subsequent studies. A total of 118 outpatients were enrolled. A daily dose of 400 mg R. rosea extract (WS® 1375, Rosalin) was administered over 12 weeks. Clinical outcomes were assessed by the German version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory, Burnout Screening Scales I and II, Sheehan Disability Scale, Perceived Stress Questionnaire, Number Connection Test, Multidimensional Mood State Questionnaire, Numerical Analogue Scales for different stress symptoms and impairment of sexual life, Patient Sexual Function Questionnaire, and the Clinical Global Impression Scales.

Results: The majority of the outcome measures showed clear improvement over time. Several parameters had already improved after 1 week of treatment and continued to improve further up to the end of the study. The incidence of adverse events was low with 0.015 events per observation day.

Discussion: The trial reported here was the first to investigate clinical outcomes in patients suffering from burnout symptoms when treated with R. rosea. During administration of the study drug over the course of 12 weeks, a wide range of outcome measures associated with the syndrome clearly improved.

Conclusion: The results presented provide an encouraging basis for clinical trials further investigating the clinical outcomes of R. rosea extract in patients with the burnout syndrome.

Keywords: burnout, clinical study, Rhodiola rosea

Introduction

The burnout syndrome poses an increasing challenge to socioeconomics in the Western world.1 This study reports an exploratory clinical trial investigating clinical outcomes of Rhodiola rosea treatment in patients suffering from burnout symptoms.

The core indicators of the syndrome are subjective perceptions of chronic demand-related stress with subsequent emotional exhaustion and decreased performance in work-related or self-set tasks.1–9 Reported symptoms of burnout are manifold, comprising not only psychiatric or mood disorders such as fatigue, cynicism, impaired sexual life, lack of concentration, or a generally negative attitude toward work, but also somatic symptoms such as headaches, hypertonia, or irritable stomach.6,9 It is also agreed that the development of the syndrome bears a considerable risk of subsequent serious mental or somatic disorders, among which depression, anxiety, and cardiovascular conditions are the most prevalent indications associated with a history of burnout.3,10–13

Support in preventing and alleviating stress reactions is offered by adaptogenic substances which are reported to potentially enhance individual stress tolerance.14–18 R. rosea is one of the most popular herbal medicinal plants with adaptogenic properties.19 As in all adaptogens, the pharmacodynamic characteristics of R. rosea include near-non-toxicity and a nonspecific effect that increases the resistance of the organism to adverse biochemical and physical factors.14 Unlike proper central nervous system stimulants, R. rosea is reported to enhance the performance without causing a subsequent substantial decrease in work capacity and to provide mental stimulation combined with emotional stabilization.12,18,20–22

The roots and rhizomes of R. rosea contain several medically active compounds, that is, phenolic acids, triterpenes, monoterpenes, flavonoids, phenylethanol derivatives, and the phenylpropanoids such as rosavin, rosin, and rosarin. The latter have as yet only been found in R. rosea.23 R. rosea’s dry extract has a long tradition as a herbal medicinal product administered for alleviating stress-related symptoms such as fatigue or sensation of weakness.14

Based on this knowledge, various clinical trials have recently assessed R. rosea in subjects with stress-related conditions. Edwards et al demonstrated not only a clinically relevant improvement in subjects suffering from life-stress symptoms after administration of R. rosea extract but also the safety of the drug.24 Other trials evaluating the effects of R. rosea extract in improving the physical and mental performance under stressful conditions confirm and support these findings.25,26

Investigating the effects of R. rosea on burnout-related symptoms, Olsson et al demonstrated the superiority of R. rosea extract over placebo in alleviating mental fatigue as measured by the Pines burnout scale.27 A German noninterventional study conducted in 128 general practitioner (GP) practices including 330 patients with two or more burnout indicator symptoms, as assessed on a basic, self-rating questionnaire, also reported a considerable alleviation of these symptoms after the administration of R. rosea extract for 8 weeks.28 Beneficial effects of R. rosea extract on emotional instability and somatization as symptoms of mild to moderate depression were demonstrated by Darbynian et al.29 This is of particular interest as these symptoms – when associated with stress – are also regarded as indicators of burnout.6,9

Both traditional knowledge and the results of these recent studies support the use of R. rosea for stress-related symptoms such as fatigue or lack of performance. These findings suggest that R. rosea might also be beneficial in burnout and that further testing of the drug in patients suffering from this stress-related syndrome is warranted.

The trial reported here not only investigated individual aspects of stress-related conditions and indicators of burnout but aimed to cover as many aspects as possible, including individual perceptions of stress and exhaustion, and to compare these with objective assessments. Thus, a rounded set of criteria for the evaluation of the clinical course in burnout was provided. This trial is therefore the first to investigate the clinical outcomes of R. rosea treatment in patients with predefined burnout symptoms based on numerous specific criteria and measurements.

Objective

The trial presented in this study is the first to investigate the clinical outcomes of the drug treatment in patients suffering from burnout syndrome. The principal objective of the trial was therefore to describe the therapeutic impacts as well as the safety and tolerability of R. rosea extract applied in this target group, thus providing exploratory data as a basis for future randomized trials.

Methods

According to its exploratory design, which aimed to evaluate the study data on a descriptive level, the trial was set up as an open-label, single-arm, multicenter study. Control groups and randomization were therefore unnecessary. The trial was conducted at four centers in Vienna (Austria): Vienna University Hospital and three GP practices. Signed informed consent was obtained from the participants before any trial-related action was performed. The clinical trial number for this study is ISRCTN31235821. The clinical trial was approved by the Ethikkommission der Medizinischen Universität Wien und des AKH, Borschkegasse 8b/E06, A-1090 Wien, Vienna, Austria, which officiated as the responsible ethics committee. Planning, execution, and analysis of the trial were carried out in accordance with national regulations in Austria and the ICH Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice (GCP).

Participants

The trial aimed to recruit 120 male and female employees or subjects with comparable stress burdens (eg, home caring of handicapped or demented family members) aged 30–60 years suffering from burnout symptoms.

Outcome measures

Since no data are available in this study-specific target population, the following broad spectrum of outcome measures was employed to evaluate the clinical courses in patients suffering from burnout symptoms.

The Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI-D),1 seven Numerical Analogue Scales (NASs) of subjective stress symptoms, one NAS to assess the “overall satisfaction with sexual life,” the Burnout Screening Scales (BOSS I and BOSS II),30 the Patient Sexual Function Questionnaire (PSFQ),31,32 and the Perceived Stress Questionnaire (PSQ).33 The Clinical Global Impressions Scale (CGI)34 were used to assess the severity of the disorder and its change from baseline, clinical outcomes, and the tolerability of the study medication. Mood and well-being were measured by means of the Multidimensional Mood State Questionnaire (MDMQ).35 These tools were all self-rating instruments. In addition, the following objective scales were employed: the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS)36 to assess the negative impact of the burnout symptoms on the patient’s work, social life, and family, and the Number Connection Test (NCT)37 to assess speed of executive function.

Eligibility

The inclusion criteria were as follows: moderate degree of burnout with an emotional exhaustion level of 1.81–2.80 and a reduced personal performance level of 3.90–4.79 according to the MBI-D, at least three perceived life stress symptoms with a severity between 5 and 8 points as assessed on NASs of subjective stress symptoms, a CGI item 1 score <4, and >5 points on the NAS for impairment of sexual life.

Patients with any of the following characteristics were excluded: Participation in other experimental drug trials within 12 weeks before enrollment, current hospitalization, risk of suicide or item 3 of the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D)38 >2, history or evidence of substance abuse or dependence, history of Axis I disorders according to DSM-IV, nonmedical psychiatric treatment at least 4 weeks before the study, intake of any prescribed psychotropic medication within 1 year before enrollment, and known hypersensitivity to R. rosea extract or any ingredient of the drug under study.

Concomitant treatment prohibited for study participants also included treatment for neurodegenerative diseases, centrally acting antihypertensive medication (exception: beta-blockers on dosage stable for at least 4 weeks), and muscle relaxants.

Laboratory tests and electrocardiogram (ECG) were assessed for abnormalities. Existing cardiovascular, respiratory, cerebrovascular, or metabolic disorders as well as infections, epilepsy, Parkinson’s disease, and progressive diseases such as cancer precluded inclusion. Subjects with generalized anxiety disorder according to module O of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI)39 or major depression according to module A of the MINI and having a total score ≥16 on the HAM-D (17-item version) at screening were also excluded from the trial.

Intervention

The active ingredient of the preparation is a proprietary dry ethanolic (60% w/w) extract from R. rosea roots (1.5–5:1) (WS® 1375, Rosalin; which is the active substance of Vitango®, manufactured by Dr Willmar Schwabe GmbH & Co, KG, Germany). Evidence from previously conducted clinical trials24,26,29 indicates the 400 mg/day dosage of study medication chosen for this study to be in an effective and a safe administration range.

After the determination of trial eligibility, the patients were screened for inclusion and exclusion criteria on day-2. Patients were enrolled upon meeting all the criteria, and written informed consent was obtained from all the patients. After the baseline visit (day 0), patients underwent a treatment with 200 mg of R. rosea extract administered twice daily over a treatment duration of 12 weeks. Patients were asked to take one 200 mg tablet before breakfast and one before lunch with a glass of water.

Regular visits were scheduled for days 0 and 7 as well as for weeks 4 (telephone interview), 8, and 12 (termination visit). Given the comparatively long treatment duration chosen for the trial, this schedule of visits was set in order to allow the investigators to capture data regarding both short-term and delayed impacts of the study medication.

All the outcome variables were measured at screening and at week 12. BOSS I was additionally assessed at week 8, whereas BOSS II, NASs for subjective stress symptoms, NCT, MDMQ, and CGI were additionally assessed at day 7 and week 8.

Safety and tolerability were assessed by physical examination, vital sign measurements, 12-lead ECG, and laboratory tests at screening and end of treatment. The patients were asked about adverse events (AEs) and concomitant medication at every visit. The severity and causal relationships of AEs with the test drug were classified by the respective investigator according to standards set by ICH-GCP.

Statistical methods

The rating scales were assessed and evaluated in an exploratory data analysis in order to support the results of earlier trials regarding the treatment of mental and physical symptoms of stress and overwork such as fatigue and exhaustion. Therefore, no hypotheses were formulated and no formal estimation of sample size accounting for type I error rate, power, standard deviation, and effect size was done. Because of the exploratory characteristics of the trial, no adjustments for multiplicity were applied.

The sample size of 120 participants was regarded as sufficient in order to obtain primary information about the clinical outcomes in the target group and to derive estimates regarding variability. Calculations were based on a one-group multivariate repeated measures design for a two-sided test, five time points, and a descriptive significance level α=0.5. This results in a power of 80% to detect a minimum standardized difference of 0.5 when recruiting 120 participants – including a 10% dropout rate.40

The absolute and relative intra-individual changes during the time courses of the outcome parameters were evaluated. Descriptive statistics were computed to describe the empirical distributions, 95% confidence intervals for the expected values and medians were calculated, and descriptive P-values associated with appropriate statistical tests were presented. In order to analyze not only the main effects but also the interaction effects on various outcome variables, for example, between time and gender, repeated measurement analysis of variance was applied. Statistical analysis was performed by a CRO using the SAS® statistical software package (Statistical Analysis System; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA, Version 9.1.3).

The analysis was primarily based on the full analysis set (FAS) including all participants who had received at least one dose of R. rosea and who had had at least one post-screening measurement on one of the rating scales (MBI-D, BOSS I+II, NAS, PSQ, NCT, SDS, MDMQ, PSFQ, and CGI). In addition, a per-protocol (PP) analysis was performed including those patients of the FAS without major protocol violations. Safety variables were assessed for the safety population which included all patients who were given study medication at least once.

Results

Participant flow

In total, 131 patients were screened and 118 patients were finally included in the study and received the investigational treatment at least once. The first patient was included on July 21, 2011, and the last visit of the last patient was conducted on October 24, 2012. One patient was lost to follow-up without any post-baseline measurement. Thus, 117 patients could be included in the FAS. During the treatment phase, 18 patients (15.3%) terminated the study prematurely. Major protocol violations were observed in 49 patients; therefore, a total of 68 patients were included in the per-protocol set (PPS). Most of the major protocol violations were due to reduced visit schedule compliance (n=30).

In the following, only the outcome data of the FAS are shown since the analysis of the FAS and the PPS revealed similar results. The disposition of patients and analysis data sets are illustrated in Figure 1.

| Figure 1 Disposition of patients and analysis of data sets. |

Demographic characteristics

The analysis of the MINI assessments showed that 4/117 patients (3.4%) reported a former episode of major depression, 8/117 (7%) had a low suicidal risk, whereas a current panic attack, a current agoraphobia, and a current bulimia nervosa were reported by one patient each. No further neuropsychiatric disorders were detectable among the FAS members. The analysis of the HAM-D showed an average total score (± standard deviation) of 10.2±2.5 points at screening, which indicates only mild depressive symptoms in the FAS cohort. 40/117 patients (34.2%) had already been treated for stress-related complaints in the past. The average duration of stress was 2.7±3.0 years. Demographic data are summarized in Table 1.

| Table 1 Demographic data: absolute (relative) frequency and mean ± standard deviation, FAS (N=117) |

The overall treatment compliance evaluated according to the number of tablets dispensed and returned in relation to the respective number of treatment days, was high. In the FAS, the average compliance was 98.6%±6.1% with a median of 99.4%.

Clinical outcomes

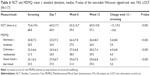

A decrease by 0.4±1.2 and 0.3±1.0 points, respectively, was observed in the MBI-D subscales “depersonalization” and “emotional exhaustion” between screening and week 12. No change could be detected in the subscales “involvement” and “personal accomplishment” (Table 2).

Figure 2 illustrates the time courses of the NASs for subjective stress symptoms. All the seven items showed significant improvement between screening and week 12, with the greatest change occurring during the first week of treatment (P<0.001, two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test, FAS, and last observation carried forward [LOCF]). Subscores with the most obvious change were “exhaustion,” “impaired concentration,” and “somatic symptoms,” with a decrease by 3.1±2.8, 2.5±2.6, and 2.4±2.5 points, respectively, at week 12.

| Figure 2 NAS for subjective stress symptoms. |

All subscores of the PSQ as well as the total PSQ global score distinctly decreased between screening and end of the intervention period. The PSQ subscores with the greatest change after 12 weeks of administration of R. rosea were “lack of joy,” “tension,” and “fatigue,” which improved by 2.8±4.1, 2.4±2.6, and 2.4±3.0, respectively (Table 3).

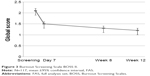

Table 4 summarizes the total average values for the BOSS I and II assessments before and after the intervention period. The global scores as well as all subscales had improved at week 8 and also until week 12. The BOSS II interim measurement at day 7 showed an alleviation of symptoms (Table 4 and Figure 3).

| Figure 3 Burnout Screening Scale BOSS II. |

The NAS score for Impairment of Sexual Life improved considerably, as well as most of the items of the PSFQ. The improvement of the “ability to have and/or maintain an erection” was marked though not statistically significant, while the “ability to ejaculate” and “relevance of sexual functioning for current wellbeing” remained mainly unchanged. For both the items, mild impairment had been reported at screening (Table 5).

NCT values increased distinctly between screening and week 12. All the three subscales of the MDMQ also showed marked improvement from screening to week 12 (Table 6).

The global impairment score measured by the SDS decreased from 17.8±5.8 at screening to 12.4±7.7 at week 12 (P<0.001). There was also a trend toward the reduction in the subscore “work days lost” (1.0±2.3 vs 0.6±1.3, P=0.063) and a significant reduction in the second subscore “days being underproductive” (2.5±2.4 vs 1.5±1.8, P<0.001 for the two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test, FAS, LOCF).

The CGI scores for therapeutic effects showed a “marked” improvement in 49/117 (41.9%) patients after 12 weeks of treatment, whereas the improvement of symptoms was reported to be “moderate” in 26/117 (22.2%), and “minimal” in 30/117 (25.6%) of the patients. In 8/117 patients (6.8%), symptoms were rated as unchanged or worse. Comparable results were obtained for the rating of global improvement after the treatment period, which was reported to be “very much,” “much,” or “minimally” the case in 41/117 (35.0%), 26/117 (22.2%), and 34/117 (29.1%) patients, respectively. The mean “severity” score had significantly dropped from 3.4±0.7 at screening to 2.4±1.1 at week 12 (P<0.001).

In addition to the overall analysis, all rating scales were analyzed with regard to gender and age subgroups (separated by the median) for both the FAS and PPS. In summary, all relevant changes in outcome variables for the whole study population could also be confirmed within each subgroup.

Safety

The participants representing the safety population were given the investigational product between 3 and 98 days with a mean treatment duration of 81.3±18.0 days. A total of 145 AEs, which were either reported by the trial participants or revealed by the investigator at scheduled visits, were observed in 70/118 (59.3%) patients during the active treatment phase and a subsequent 7 days risk phase. AE intensity was predominantly rated as mild (59/145 [40.7%]) or moderate (68/145 [46.9%]), and severe (18/145 [12.4%]). For 46/145 AEs (31.7%), a causal relationship with the investigational product could not be excluded but was assessed as “unlikely” in 41/46 (89.1%) cases. A causal relationship with the study drug was rated “possible” in 5/46 (10.9%) subjects who reported head pressure, light-headedness, nausea, feeling irritated, and eye swelling. One serious adverse event (SAE) occurred in a male subject who had to be hospitalized for 3 days due to urinary tract infection after cystoscopy. The SAE was assessed as “not related” to the investigational product and had resolved at the end of the study. Except for this case of hospitalization, no other SAE was reported. The calculated overall incidence of AEs per observation day was 0.015 and was found to be low during the whole study period. None of the safety laboratory parameters presented a significant mean change during the course of the study. The AEs are summarized in Table 7.

Discussion

Most of the outcome variables assessed in this trial demonstrated relevant improvement over time with considerable changes already being detectable after the first week of R. rosea administration.

As stress-induced exhaustion is regarded as an essential precondition to burnout development, this outcome was of central interest in the evaluation of study assessments. The level of “emotional exhaustion” as assessed by the MBI-D at screening was moderate and improved clearly over the time of the intervention. Likewise, the PSQ-assessed “fatigue” value and the subscore “exhaustion,” as assessed by the respective NASs, had already clearly improved by day 7 and further decreased until the end of the intervention. Furthermore, the other subscales assessed by the NASs for subjective stress symptoms underwent significant improvement, which suggests an increase in coping ability and a decrease in subjectively perceived demand after the intervention.

Mood-related results improved in a similar way with “lack of joy” undergoing the greatest improvement among the values assessed by PSQ. Accordingly, there was a clear improvement of the value “loss of zest for life” as assessed by NAS, suggesting a diminished tendency toward stress-related depressive mood.

Overall, the data obtained by PSQ and the NASs for subjective stress symptoms demonstrate improvement in all the assessed values, which was most pronounced within the first week of treatment and continued slowly afterwards. The values most closely associated with burnout were among those with greatest improvement. The results suggest a development toward re-establishment of a demand–resource balance, thus supporting the findings from earlier placebo-controlled trials that investigated the clinical outcomes of R. rosea treatment for stress-related symptoms25–27 and for the symptoms of depression.29

Although the MBI-D subscale “depersonalization” improved over time, there was no detectable improvement in the scales “involvement” and “personal accomplishment.” This result is in contrast to the marked improvement in the NCT, which objectively measures executive function and performance, and the clearly improved alertness value, as measured by the MDMQ. The contradiction between self-rating and objective outcome regarding “personal accomplishment” is in line with what is known about the essential role of individual perception of achievement in burnout, which often deviates from objective evaluation.5

The BOSS assessment results demonstrate that over the 12-week course of treatment the subjective perception of different aspects of life (profession, own person, family, and friends) as well as physical, cognitive, and emotional complaints improved clearly. The average global and subvalues of the BOSS I and the BOSS II assessments thus reflect a perception of reduced global- and aspect-related stress burdens.

Comparing the results of BOSS I and II with a representative normative German sample clearly shows that at the beginning of the study the participants reported clinically relevant psychological, physical, and psychosocial complaints (global score T-values 65 and 63 for BOSS I and II, respectively). This global score finally decreased to a normal value after the 12-week treatment phase with R. rosea (global T-value 54 and 53 for BOSS I and II, respectively).

Increased sexual interest and functioning as determined by the NAS for Impairment of Sexual Life and the PSFQ are obvious and indicate an alleviation of stress-induced impairment of sex life after the intervention. These results are in line with earlier findings on the causal relationship of life-stress, anxiety, and depression with sexual dysfunction41,42 and support the assumption of an impairing effect of burnout on sexual functioning.

The evaluation of therapeutic effects as assessed by the respective CGI item before and after the intervention period shows that at least a minimal improvement of the disorder is reported by the vast majority of patients (105/117 or 89.7%). This suggests therapeutic efficacy of R. rosea extract in burnout.

Despite the observed quick and distinct improvement of most of the outcome parameters during the first week of intervention, which might at first glance not seem to be in accordance with what is known about the usually rather slow process of burnout therapy, it is still in line with what is known about the gradual development of burnout.6 In this context, the outcomes of the PSQ and NAS assessment suggest that the reduction of core values such as exhaustion, fatigue, and subjective stress perception during the treatment with R. rosea extract might be an important first step toward a continuous alleviation of burnout symptoms, thus inhibiting the exacerbation of the syndrome and preventing the development of subsequent disorders such as depression or physical illness.

The lack of a control in the trial reported here must be considered a limitation. The results thus remain preliminary and may not be considered confirmatory. Nevertheless, the considerable improvements found for most of the outcome measures reveal positive trends in burnout therapy. No symptom alleviation can be expected without treatment. The trial results are therefore important to help generate hypotheses for further research and provide bases for confirmatory study design, endpoints, and methodologies.43

The steady and substantial alleviation of the majority of the burnout symptoms assessed was statistically relevant for the variables evaluated for the FAS as early as 1 week after the start of treatment. The consistent overall results were further confirmed by the analyses of the PPS, subgroup analyses, and repeated measurement analyses. The results obtained are in line with the findings from previously conducted clinical trials on the clinical outcomes of R. rosea in different aspects of the burnout syndrome such as stress and depression.

The number and nature of AEs that occurred during the trial indicate a favorable safety profile of R. rosea in patients suffering from burnout symptoms, which is also underlined by the remarkably high treatment compliance.

Conclusion

The trial reported here was the first to investigate clinical outcomes in patients suffering from burnout symptoms when treated with R. rosea. During administration of the study drug over the course of 12 weeks, a wide range of outcome measures associated with the syndrome clearly improved. The consistent data obtained support the claim that the results of this open-label exploratory study are in line with previous findings on the alleviation of life-stress and burnout symptoms by application of R. rosea. The results presented therefore provide an encouraging basis for future RCTs further investigating the clinical outcomes of R. rosea extract in patients with the burnout syndrome.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the investigators who took part in this trial. They thank Christine Weidl who provided support in medical writing. All the authors contributed equally to the preparation of the manuscript.

Disclosure

Siegfried Kasper has received grant/research support, consulting fees, and/or honoraria within the last 3 years from Angelini, AOP Orphan Pharmaceuticals AG, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Janssen, KRKA-Pharma, Lundbeck, Neuraxpharm, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, Schwabe, and Servier. Dr Dienel is an employee of Dr Willmar Schwabe GmbH & Co. KG.

References

Korczak D, Kister C, Huber B. Differentialdiagnostik des Burnout-Syndroms. Schriftenreihe Health Technology Assessment, vol 105. Köln: DIMDI; 2010. | ||

Freudenberger, HJ. Staff burn-out. J Soc Issues. 1974;30:159–165. | ||

Positionspapier der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie, Psychotherapie und Nervenheilkunde (DGPPN) zum Thema Burnout (07.03.2012). Available from: https://www.dgppn.de/aktuelles/detailansicht/article//positionspap-1.html. Accessed April 1, 2016. | ||

Demerouti E, Bakker AB, de Jonge J, Janssen PPM, Schaufeli WB. Burnout and engagement at work as functions of demand and control. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2001;27:279–286. | ||

Maslach C. Burnout: The Cost of Caring. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1982. | ||

Weber A, Jaekle-Reinhard A. Burnout syndrome: a disease of modern societies? Occup Med. 2000;50:512–517. | ||

Plieger T, Melchers M, Montag C, Meermann R, Reuter M. Life stress as potential risk factor for depression and burnout. Burnout Res. 2015;2:19–24. | ||

Taris TW, Le Blanc PM, Schaufeli WB, Schreurs PJG. Are there causal relationships between the dimensions of the Maslach Burnout Inventory? A review and two longitudinal tests. Work Stress. 2005;19:238–255. | ||

Schaufeli W, Enzmann D. The Burnout Companion to Study and Practice. A Critical Analysis. London: Taylor & Francis; 1998. | ||

Mommersteeg P, Heijnen CJ, Kavelaars A, van Doornen LPJ. Immune and endocrine function in burnout syndrome. Psychosom Med. 2006; 68:879–886. | ||

Limm H, Gündel H, Heinmüller M, et al. Stress management interventions in the workplace improve stress reactivity: a randomized controlled trial. Occup Environ Med. 2011;68:126–133. | ||

Ploss O. Naturheilkunde bei funktionellen Erkrankungen: Von Reizdarm bis Burn-out-Syndrom. Stuttgart: Thieme; 2012. | ||

Honkonen T, Ahola K, Pertovaara M, et al. The association between burnout and physical illness in the general population – results from the Finnish Health 2000 Study. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61:59–66. | ||

EMA/HMPC/232100/2011. Community herbal monograph on Rhodiola rosea L., rhizoma et radix 27 May 2012. Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC). London: EMA; 2012. | ||

Selye H. The general adaptation syndrome and the diseases of adaptation. J Clin Endocrinol. 1946;6:117–231. | ||

Lazarev NV. General and specific in action of pharmacological agents. Farmacol Toxicol. 1958;21:81–86. | ||

Panossian AG, Wikman G, Sarris J. Rosenroot (Rhodiola rosea): Traditional use, chemical composition, pharmacology and clinical efficacy. Phytomedicine. 2010;17:481–493. | ||

Brekhman II, Dardymov IV. New substances of plant origin which increase nonspecific resistance. Ann Rev Pharmacol. 1969;9:419–430. | ||

EMA/HMPC/102655/2007. Reflection paper on the adaptogenic concept 8 May 2008. Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC). London: EMA; 2008. | ||

Brown RP, Gerbarg PL, Ramazanov Z. Rhodiola rosea. A phytomedicinal overview. Herbal Gram. 2002;56:40–52. | ||

Panossian AG, Wagner H. Stimulating effect of adaptogens: an overview with particular reference to their efficacy following single dose administration. Phytother Res. 2012;10:819–838. | ||

WHO. Revised Draft Monography on Radix Rhodiolae roseae. Geneva: WHO; 2005. | ||

Dubichev AG, Kurkin BA, Zapesochnaya GG, Vornotzov ED. Study of Rhodiola rosea root chemical composition using HPLC. Khim Prirodn Soedin. 1991;5(2):188–193. | ||

Edwards D, Heufelder A, Zimmermann A. Therapeutic effects and safety of Rhodiola rosea Extract WS® 1375 in subjects with life-stress symptoms – results of an open-label study. Phytoter Res. 2012;26:1220–1225. | ||

Spasov AA, Wikman GK, Mandrikov VB, Mironova IA, Neumoin VV. A double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of the stimulating and adaptogenic effect of Rhodiola rosea SHR-5 extract on the fatigue of students caused by stress during an examination period with a repeated low-dose regimen. Phytomedicine. 2000;7:85–89. | ||

Darbinyan V, Kteyan A, Panossian AG, Gabrielian E, Wikman G, Wagner H. Rhodiola rosea in stress-induced fatigue – a double-blind cross-over study of a standardized extract SHR-5 with a repeated low-dose regimen on the mental performance of healthy physicians during night duty. Phytomedicine. 2000;7:365–371. | ||

Olsson EM, von Schéele B, Panossian AG. A randomized, double-blind-, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study of the standardized extract SHR-5 of the roots of Rhodiola rosea in the treatment of subjects with stress-related fatigue. Planta Med. 2009;75:105–112. | ||

Goyvaerts B, Bruhn S. Rhodiola rosea Spezialextrakt SHR-5 bei Burnout und Erschöpfungssyndrom. EHK. 2012;61:79–83. | ||

Darbynian V, Aslanyan G, Amroyan E, Gabrielyan E, Malmström C, Panossian A. Clinical trial of Rhodiola rosea L. extract SHR-5 in the treatment of mild to moderate depression. Nord J Psychiatry. 2007;61:343–348. | ||

Hagemann W, Geuerich K. BOSS Burnout-Screening-Skalen, Manual. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 2009. | ||

Philipp M, Delini-Stula A, Baier D, Kohnen R, Scholz HJ, Laux G. Assessment of sexual dysfunction in depressed patients and reporting attitudes in routine daily practice: results of the post-marketing observational studies with moclobemide, a reversible MAO-A inhibitor. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 1999;3:257–264. | ||

Philipp M, Tiller JWG, Baier D, Kohnen R. Comparison of moclobemide and SSRIs on sexual function in depressed adults. Eur Neuropsychopharm. 2000;10:305–314. | ||

Levenstein S, Prantera C, Varvo V, et al. Development of the perceived stress questionnaire: a new tool for psychosomatic research. J Psychosom Res. 1993;37:19–32. | ||

Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare Public Health Service Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration; 1976. | ||

Steyer R, Schwenkmezger P, Notz P, Eid M. MDBF – Mehrdimensionaler Befindlichkeitsfragebogen (Multidimensional Mood Questionnaire). Göttingen: Hogrefe; 1997. | ||

Sheehan DV, Harnett-Sheehan K, Raj BA. The measurement of disability. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996;11(Suppl 3):89–95. | ||

Oswald WD, Roth E. Der Zahlen-Verbindungs-Test (ZVT). Ein sprachfreier Intelligenz-Test zur Messung der “kognitiven Leistungsgeschwindigkeit”[The Number Connection Test. A non-verbal intelligence test to measure cognitive speed of performance]. 2nd ed. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 1987. | ||

Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosur Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. | ||

Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33. | ||

Guo X, Johnson WD. Sample sizes for experiments with multivariate repeated measures. J Biopharm Stat. 1996;6:155–176. | ||

Stulhofer A, Træen B, Carvalheira A. Job-related strain and sexual health difficulties among heterosexual men from three European countries: the role of culture and emotional support. J Sex Med. 2013;10:747–756. | ||

Træen B, Martinussen M, Öberg K, Kavli H. Reduced sexual desire in a random sample of Norwegian couples. Sex Rel Ther. 2007;22:303. | ||

EMA/CPMP/ICH/291/95: ICH Topic E 8: General Considerations for Clinical Trials. London; 1998. |

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.