Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 17

Mothers’ Perceived Co-Parenting and Preschooler’s Problem Behaviors: The Mediating Role of Maternal Parenting Stress and the Moderating Role of Family Resilience

Received 15 December 2023

Accepted for publication 27 February 2024

Published 5 March 2024 Volume 2024:17 Pages 891—904

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S451870

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Mei-Chun Cheung

Jingjing Zhu, Shuhui Xiang, Yan Li

Shanghai Institute of Early Childhood Education, Shanghai Normal University, Shanghai, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Yan Li, Shanghai Institute of Early Childhood Education, Shanghai Normal University, No. 100 Guilin Road, Shanghai, 200234, People’s Republic of China, Email [email protected]

Introduction: Problem behaviors in preschoolers signals social adjustment challenges. This study investigates the mediating role of parenting stress in the relationship between co-parenting and these behaviors, and examines how family resilience impacts this dynamic.

Methods: A detailed survey was conducted with 1279 mothers of 3-6-year-olds in Shanghai, China, focusing on co-parenting, family resilience, parenting stress, and children’s behaviors. We employed SPSS 26 for initial tests and the Hayes PROCESS macro in SPSS 23.0 for advanced analysis, using bootstrap methods to assess mediation and moderation effects.

Results: The analysis revealed that maternal parenting stress mediates the relationship between co-parenting and children’s problem behaviors. Specifically, unsupportive co-parenting or low levels of supportive co-parenting heightened maternal stress, which in turn increased children’s problem behaviors. Family resilience was found to moderate this relationship, buffering the impact of unsupportive co-parenting on maternal stress. High family resilience levels were associated with lower parenting stress, regardless of co-parenting quality.

Conclusion: These findings highlight the importance of enhancing family resilience and supportive co-parenting to mitigate parenting stress and reduce problem behaviors in children. It has practical implications for developing family-centred interventions and policies to strengthen family resilience and co-parenting skills.

Keywords: co-parenting relationships, family resilience, parenting stress, problem behaviors, preschool children

Introduction

Problem behaviors in preschool deviating from typical developmental norms encompass both externalizing (eg, aggression) and internalizing dimensions (such as anxiety),1 which are early indicators of social adaptation challenges. Without appropriate attention and intervention, these behaviors can escalate into more severe issues, including social communication difficulties, academic underachievement, and potential development of antisocial behaviors.2–4 Moreover, studies indicate that early problem behaviors in preschoolers can lead to long-term risks, such as delinquency in adolescence and adulthood.3,4

There was a significant association between co-parenting relationships and children’s problem behaviors, and interventions to improve co-parenting skills reduced children’s problem behaviors.5–9 The spillover hypothesis10 and subsequent studies11,12 emphasize the indirect impact of co-parenting on children via parenting stress. Partner support in co-parenting can mitigate conflicts and reduce parenting stress.13 Additionally, family resilience is vital in managing parenting stress,13,14 suggesting its potential moderating role in the co-parenting-parenting stress dynamic. Thus, this study examines the interplay between co-parenting, family resilience, parenting stress, and preschoolers’ problem behaviors, contributing novel insights into the mechanisms underlying these relationships.

Co-Parenting Relationships and Problem Behaviors

Within the framework of family systems theory, co-parenting, a distinctive family subsystem, plays a pivotal role in shaping the adjustment of parents and children when families encounter risks.15,16 Co-parenting describes how parents’ collaborative management of child-rearing responsibilities encompasses supportive and unsupportive forms.17–20

The ecological model of co-parenting suggests that supportive co-parenting, characterized by mutual reinforcement and respect, positively influences child development.21 In contrast, unsupportive co-parenting, involving conflict and undermining, negatively impacts children’s adjustment.18,21 For instance, Zhang et al observed that supportive co-parenting had a negative predictive impact on externalizing problem behaviors in preschoolers,8 while Camisasca et al demonstrated a correlation between co-parenting conflict and problem behaviors in children aged 3–10.6 Furthermore, emotional security theory posits that exposure to parental conflict may induce emotional distress and insecurity in children, subsequently jeopardizing their psychological well-being.22,23 A study by Westrupp et al conducted a decade-long follow-up involving 3696 children and their families, revealing a significant link between early childhood experiences of parental conflict and children’s mental health in early adolescence.24 Therefore, we hypothesize that supportive co-parenting reduces, while unsupportive co-parenting increases, problem behaviors in children.

The Mediating Role of Parenting Stress

Parenting stress, as defined by Abidin (1990),2 is the result of the pressures experienced by parents, influenced by a combination of internal and external factors, and manifested in various aspects of parental roles and interactions with their children. Parenting stress is a prevalent issue within the parenting population,25 with mothers particularly susceptible to increased anxiety in challenging environments.26

Crucially, parenting stress often triggers negative parental attitudes and maladaptive parenting styles, exacerbating children’s behavioral issues. In scenarios of heightened stress, parents may adopt authoritarian or permissive approaches, imposing stricter discipline or resorting to corporal punishment, which can escalate negative parent-child interactions.27 Increased stress levels may also prompt controlling behaviors, such as verbal abuse or excessive criticism, potentially leading to child rejection and further behavioral problems.28 Notably, early childhood exposure to elevated parenting stress has long-term detrimental effects on positive development. This assertion is supported by a longitudinal study tracking 835 parent-child pairs from ages 1 to 3, which revealed that parenting stress at age 1 significantly predicted problem behaviors at age 3.29

The process model of the determinants of parenting highlights social support’s role in moderating parenting behavior and mitigating stress.30,31 Social support encompasses providing emotional support, delivering instrumental assistance, and providing social expectations. Within this framework, co-parenting emerges as a key aspect of social support, closely linked to parenting stress.18 One study discovered that supportive co-parenting significantly and negatively predicted parenting stress.32 Supportive co-parenting, involving emotional support such as love and acceptance from a partner, can directly or indirectly influence parenting.30 For instance, research by Thullen and Bonsall (2017) involving 113 children aged 5–13 and their parents indicated that parents experienced lower levels of parenting stress when they received increased validation and support from their partners, reducing the likelihood of conflicts related to parenting.33 Additionally, the ecological model of co-parenting posits that co-parenting influences parenting stress and moderates external familial risks.18

This study investigates how parenting stress mediates the influence of varying co-parenting relationships (supportive and unsupportive) on children’s problem behaviors.

The Moderating Role of Family Resilience

Family resilience, which refers to a family’s ability to cope with life’s stresses and adversities, including the family’s skills and adaptability to cope with challenges, is critical to maintaining family functioning and promoting healthy family dynamics in times of stress.34–37 This study will examine how it moderates the relationship between co-parenting relationships and parenting stress. Research demonstrates a significant inverse relationship between family resilience and parenting stress,13,38 as evidenced in studies involving low-income Brazilian families.14 The higher the levels of family resilience, the lower the levels of parenting stress perceived by parents. The importance of individual cognitive assessments of stress and family coping mechanisms in this dynamic is highlighted by Lazarus (1993) and later supported by researchers.39 Specifically, these components contribute to stress formation and serve as key indicators of family resilience.40,41 Therefore, integrating empirical and theoretical perspectives suggests that increased family resilience can reduce parenting stress.

The conceptual framework of family risk and resilience, alongside the model of family well-being, theoretically supports the investigation into how family resilience moderates the impact of co-parenting on parenting stress.42,43 This framework suggests that resilience enables families to navigate adversities effectively, such as those presented by COVID-19, thereby cushioning caregivers from the adverse effects on their well-being, particularly regarding parenting stress.43 The focus is on the interplay between the challenges posed by external risk factors and the mitigating influence of family resilience on parental well-being. Furthermore, within the context of the model of family well-being, family resilience is recognized as an integral component, contributing to overall family health and stability.42 Consequently, families with robust resilience exhibit less negative impact from external stressors on parental stress levels. Family well-being is a cornerstone of developmental parenting (eg, co-parenting).42 It implies that family resilience could affect the quality of parental co-parenting significantly. Based on these models, family resilience may play a role in modulating the impact of co-parenting on parenting stress. This modulation could occur through two potential pathways: one in which family resilience directly influences parenting stress and another in which it influences the quality of co-parenting, subsequently impacting parenting stress.

Consequently, we hypothesized that family resilience might mitigate the parenting stress that unsupportive co-parenting places on mothers, influencing children’s behaviors. Specifically, the influence of parenting stress on children’s problem behaviors may be dampened as less stressed parents are inclined to provide more positive support to their children.

The Present Study

Although the link between intra-family dynamics (eg, co-parenting relationships) and child behavior has been explored in existing research, family resilience as a moderating variable and the mediating role of maternal parenting stress have not been fully understood—the present study endeavours to fill this gap. In response, this study conducted an in-depth examination of the connection between co-parenting relationships and problem behaviors in preschool children. A conceptual model illustrating the study’s framework is depicted in Figure 1.

|

Figure 1 Overview of the hypothesized moderated mediation model. |

The influence of traditional Chinese cultural norms and established family roles has led to mothers being more involved in child-rearing activities, often resulting in elevated parenting stress.44 This increased involvement of mothers in parenting tasks contributes to a more pronounced impact of maternal parenting stress on preschool children’s behavioral issues.12,45 Consequently, this study focuses primarily on mothers’ perceptions of co-parenting and their experiences of parenting stress. Additionally, research indicates that factors such as the number of children and grandparental involvement in childcare can notably influence parenting stress.46,47 Therefore, variables including the child’s gender, age, only-child status, and grandparental involvement are incorporated as control variables in examining the influence of co-parenting relationships on preschool children’s problem behaviors.

The study had three primary objectives: (1) to explore the relationship between mothers’ perceptions of co-parenting and problem behaviors in preschool children; (2) to investigate the mediating role of parenting stress in the association between co-parenting and children’s problem behaviors; and (3) to explore the moderating role of family resilience in the link between co-parenting and parenting stress. Understanding these dynamics is critical to designing effective family interventions and support strategies to help reduce problem behaviors in preschool children.

In conclusion, this study aims to fill a gap in understanding the roles of maternal parenting stress and family resilience within co-parenting dynamics. Focusing on mothers, it examines the intricate relationships between co-parenting, parenting stress, family resilience, and problem behaviors in preschool children. Including relevant variables, such as child gender, age, and grandparental involvement, offers a comprehensive view of these dynamics.

Methods

Participants

Following the receipt of informed consent from kindergartens, teachers, and parents and the endorsement of the theoretical academic committee, a structured online survey was conducted targeting mothers of preschoolers. The data collection period is from 1 May to 10 June 2022. Participants were e-mailed a survey link through which they completed informed consent and a baseline online survey via Qualtrics. Preschool teachers were first trained by master’s degree students in preschool education (ie, teachers were instructed on how to complete the scale), and then trained preschool teachers provided detailed instructions to the children’s mothers. These educators were crucial in facilitating the mother’s understanding of the survey process, ensuring they could independently complete the questionnaires. This survey aimed to evaluate aspects such as family resilience and the problem behavior of preschool children, in addition to the mothers’ experiences of parenting stress. Once completed, these questionnaires were efficiently collected for analysis.

The study employed convenience sampling and involved participants from six kindergartens in Shanghai, encompassing various educational settings. This selection included one “model” kindergarten, two kindergartens classified as “first-level”, and three designated as “second-level”. In China, public kindergartens are categorized into four tiers: “model”, “first-level”, “second-level”, and “third-level”, with “model” kindergartens representing the highest standard of quality. This tier is followed by “first-level” and “second-level”, while “third-level” kindergartens are considered the baseline standard. The composition of our sample provides a comprehensive representation of the varying levels of kindergarten education prevalent in Shanghai.

A total of 1335 questionnaires were distributed in this survey. After deleting 53 invalid questionnaires (with apparent regular responses), 1279 valid questionnaires remained, with an effective rate of 95.81%. There were 664 girls (51.92%) and 615 boys (48.08%), with an average age of 53.48±14.84 months. The educational levels of the participating mothers varied, with a small segment of 47 mothers (3.67%) reporting high school (technical secondary school) or below education. A larger proportion of 206 mothers (16.11%) had completed junior college. The majority, 785 participants (61.38%), held a bachelor’s degree, and a significant number, 241 mothers (18.84%), had attained a master’s degree or higher. The average age among the mothers was 33.68 years, with a standard deviation of 7.32.

Measures

Co-parenting Relationships

The assessment of mothers’ perceptions of their co-parenting relationship was conducted using the Chinese version of the Parents’ Perceptions of the Co-parenting Relationship (PPCR) scale.20,48 This scale, comprising 14 items, is divided into two distinct subscales. The first, supportive co-parenting, consists of 7 items, such as “My partner backs me up when I discipline the child”, with a high Cronbach’s α reliability of 0.96. The second subscale addresses unsupportive co-parenting behaviors, also with 7 items, for instance, “My partner criticizes my parenting behavior in front of the child”, demonstrating a Cronbach’s α of 0.95. Responses were elicited on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“never”) to 5 (“always”). The interpretation of the scores is straightforward: higher scores on either subscale indicate a more robust perception of supportive or unsupportive co-parenting behaviors by the mother. Notably, the Chinese adaptation of this scale has been revised for contextual relevance and has established its reliability and validity.48

Parenting Stress

In this study, mothers were asked to complete the Parenting Stress Index (PSI),49 a comprehensive tool designed to assess various dimensions of parenting stress. The PSI encompasses three subscales: parental distress (eg, “Being tied down by parenting responsibilities after the birth of the child”), parent-child dysfunctional interaction (eg, “The child rarely smiles happily when playing with the child”), and difficult child (eg, “Feeling that the child is emotional and often unhappy”). Each subscale consists of 12 distinct items that capture different aspects of the maternal experience, such as the sense of being overwhelmed by parenting duties, the quality of interaction with the child, and the child’s behavioral challenges. Respondents rated these items on a 5-point scale from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”), with higher scores reflecting increased stress levels experienced by mothers. The scale’s internal consistency, as indicated by Cronbach’s α of 0.94, confirms its reliability in Chinese contexts.50

Problem Behavior

The study also involved mothers completing the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ),51,52 focusing on four key subscales: emotional symptoms, peer problems, hyperactivity/inattention, and conduct problems. These subscales were amalgamated into a comprehensive behavior problem scale comprising 20 items, such as “frequently losing temper or making a scene”, rated on a three-point scale (1 = “not consistent”, 3 = “completely consistent”). Higher scores on this scale indicate more pronounced problem behaviors in preschool children. In this context, the scale demonstrated a Cronbach’s α of 0.76, verifying its reliability and validity for assessing Chinese preschool children’s behaviors.53

Family Resilience

Mothers of the children participated in the survey using the Shortened Chinese Version of the Family Resilience Assessment Scale.41,54 This scale encompasses various domains such as family communication and problem solving, represented by 23 items like “Our family structure is flexible in dealing with the unexpected”. It also evaluates the family’s capacity for utilizing social resources, reflected in 3 distinct items, and their ability to maintain a positive outlook through 6 specific items. Responses were recorded on a five-point scale, ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”), with higher scores denoting greater family resilience. The scale’s Cronbach’s α coefficient in this study was 0.99, indicating its high reliability and the validity of its application in the context of Chinese children.55

Analytical Strategy

Using SPSS 26 for data examination, initial tests, including t-tests, were conducted to assess gender-based variations and the interconnections among the variables of interest. For a deeper analysis, the Hayes PROCESS macro (version 3.3), applied within the IBM SPSS Statistics 26.0, facilitated the assessment of the influence of co-parenting relationships (supportive and unsupportive co-parenting) on children’s behavioral issues. Parenting stress was examined as a mediator, while family resilience was considered a moderator within this context. The analysis, employing bootstrap estimation with 5000 samples, yielded 95% Confidence Intervals for the effects along paths “a” (between predictor and mediator), “b” (between mediator and outcome), “c” (total effect), and “d” (direct effect), thus determining the presence of mediation, which is confirmed if zero is not within the 95% confidence interval.56

Results

Common Method Bias Test

Harman’s one-factor test was conducted to consider the potential for common method bias due to all data being mother-reported in this research.57 The analysis revealed thirteen distinct common factors, each with eigenvalues exceeding 1. Notably, the first common factor explained 29.53%, substantially below the 40% threshold. This outcome suggests the absence of significant common method bias in the data, supporting the validity of the findings.

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 outlines the descriptive statistics and intercorrelations of the variables studied. T-test results revealed a notable gender disparity in problem behaviors, with boys showing higher mean scores (Mboy = 1.51, SD = 0.26) compared to girls (Mgirl = 1.44, SD = 0.25), a statistically significant difference (t = 0.12, p = 0.00). The analysis also indicated a significant inverse relationship between the age of children and both problem behaviors and parenting stress. Additionally, being an only child and the level of grandparent involvement emerged as factors negatively correlated with problem behaviors. These variables, including gender, age, only child status, and grandparent involvement, were therefore accounted for as control variables in the subsequent analytical processes.

|

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics and Intercorrelations for All Study Variables |

Table 1 highlights several significant correlations involving family resilience, parenting behaviors, and co-parenting relationships. Notably, family resilience demonstrated a substantial negative correlation with both unsupportive co-parenting, problem behaviors and parenting stress, alongside a positive correlation with supportive co-parenting practices. Furthermore, a notable positive relationship was observed between parenting stress and both problem behaviors and unsupportive co-parenting, contrasted by a negative association with supportive co-parenting. Additionally, problem behaviors showed a negative correlation with supportive co-parenting and a positive relationship with unsupportive co-parenting.

The Mediating Role of Parenting Stress

The principal objective of the present study was to investigate the mediating role of parenting stress in the relationships between supportive and unsupportive co-parenting and problem behaviors. The findings are presented in Figures 2 and 3.

|

Figure 2 The mediating model of parenting stress on problem behaviors through supportive co-parenting. Note: ***p<0.001. |

|

Figure 3 The mediating model of parenting stress on problem behaviors through unsupportive co-parenting. Note: ***p<0.001. |

In Figure 2, a significant effect (path “a”) of supportive co-parenting on parenting stress was observed, revealing a negative relationship. Specifically, higher levels of supportive co-parenting were associated with lower levels of parenting stress (β = −0.25, t = −9.07, p = 0.00). Furthermore, it was found that supportive co-parenting significantly and negatively predicted problem behaviors (β = −0.18, t = −6.56, p = 0.00). In contrast, parenting stress significantly and positively predicted problem behaviors (β = 0.37, t = 14.42, p = 0.00).

As depicted in Figure 3, the analysis revealed a significant influence of unsupportive co-parenting on parenting stress (path “a”), where increased levels of unsupportive co-parenting were associated with heightened parenting stress (β = 0.36, t = 13.71, p = 0.00). In addition, unsupportive co-parenting was found to be a significant predictor of problem behaviors in children (β = 0.13, t = 4.69, p = 0.00). Crucially, the role of parenting stress as a mediating factor was substantiated; it not only predicted problem behaviors significantly (β = 0.39, t = 14.54, p = 0.00) but also altered the relationship between unsupportive co-parenting and problem behaviors. Including the mediator, the direct effect of unsupportive co-parenting on problem behaviors was notably reduced and became statistically insignificant. This shift is demonstrated by the total effect (path “c”) being 0.13 and the direct effect (path “d”) being 0.01, with the value “zero” falling within the 95% confidence interval. It indicates a significant mediating effect of parenting stress in this relationship.

This analysis employed estimation based on 5000 bootstrapped samples to assess the mediating variable and provide 95% Confidence Intervals for model coefficients. The results are presented in Tables 2 and 3.

|

Table 2 Path Coefficient Analysis of Mediation Model (Supportive Co-Parenting) |

|

Table 3 Path Coefficient Analysis of Mediation Model (Unsupportive Co-Parenting) |

In Table 2, the results revealed that the direct effect value was 0.09, the indirect effect value was 0.09, and the total indirect effect value was 0.18. Additionally, the value of “zero” fell outside the 95% confidence interval for path “e” (indirect effect of supportive co-parenting on problem behaviors) and path “d” (direct effect of supportive co-parenting on problem behaviors). These findings suggest that parenting stress is partially mediated between supportive co-parenting and problem behaviors.

In Table 3, the results indicated that the direct effect value was 0.01, the indirect effect value was 0.14. The total indirect effect value was 0.13. Furthermore, the value of “zero” fell outside the 95% confidence interval for path “e” (indirect effect of unsupportive co-parenting on problem behaviors). In comparison, it fell within the 95% confidence interval for path “d” (direct effect of unsupportive co-parenting on problem behaviors). These results imply that parenting stress fully mediated the relationship between unsupportive co-parenting and problem behaviors.

The Moderating Role of Family Resilience

The objective of the subsequent analyses was to investigate the moderating influence of family resilience in the relationships between supportive and unsupportive co-parenting and parenting stress, with the inclusion of controls for gender, age, involvement of grandparents, and only child status. The regression results are presented in Table 4.

|

Table 4 Effects of Co-Parenting Relationships, Family Resilience in Relation to Parenting Stress |

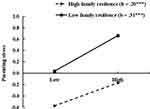

The results revealed significant interaction effects concerning parenting stress between unsupportive co-parenting and family resilience. However, no significant moderating effect of family resilience was found in the relationship between supportive co-parenting and parenting stress. To further elucidate these significant two-way interactions, simple slope analyses were conducted for unsupportive co-parenting at high and low family resilience values (1 SD above and 1 SD below the mean), following the approach outlined by Aiken et al.58 The results of the simple slopes are visually presented in Figure 4. As depicted in Figure 4, unsupportive co-parenting exhibited a negative association with parenting stress for mothers characterized by high family resilience (b = 0.20, t = 5.89, p = 0.00). Similarly, this association was significant for mothers characterized by low family resilience (b = 0.31, t = 9.18, p = 0.00).

|

Figure 4 Interaction between unsupportive co-parenting and family resilience on parenting stress. |

Discussion

This study aimed to explore the indirect impact of Chinese mothers’ perceptions of co-parenting on children’s problem behaviors, with maternal parenting stress as a mediating factor, while considering family resilience as a moderator in this pathway. In accordance with the assumptions of the process model of the determinants of parenting,30 it is posited that co-parenting can indirectly influence child development, specifically problem behaviors, through its impact on parenting stress. Furthermore, drawing from the conceptual framework of family risk and resilience and the model of family well-being,42,43 this research sought to investigate the potential moderating role of family resilience in the relationship between co-parenting and parenting stress.

The findings further enrich the literature focusing on child development by suggesting that mothers’ perceptions of co-parenting indirectly influence children’s problem behaviors through mothers’ parenting stress. At the same time, family resilience can influence children’s problem behaviors by moderating the impact of co-parenting on parenting stress and, ultimately.

Co-Parenting Relationships and Problem Behaviors

This study discovered a robust relationship between supportive co-parenting and problem behaviors in preschool children, with a significant negative association. Conversely, unsupportive co-parenting displayed a significant positive relationship with problem behaviors in these children. In other words, when supportive co-parenting exhibited higher levels and unsupportive co-parenting was lower, preschool children demonstrated fewer problem behaviors. These findings are consistent with the results of studies conducted in various cultural contexts6,8 and support the ecological model of co-parenting.18

Supportive co-parenting contributes to creating a low-stress, harmonious family environment for children. Such a positive and well-functioning family environment proves conducive to enhancing children’s psychological well-being, thereby reducing the incidence of their externalized problem behaviors.8,59 Following social learning theory, observation and imitation play a pivotal role in children’s social learning.60 When mothers actively co-parent with their partners, having calm, cooperative, and supportive interactions, children are inclined to model and internalize these relational patterns. This results in more prosocial behaviors and a decreased likelihood of problem behaviors.61,62 This research underscores the importance of promoting supportive co-parenting practices for preschool teachers or professionals working with families. Creating a low-stress, harmonious family environment enhances children’s psychological well-being and reduces the likelihood of problem behaviors. Moreover, professionals must encourage parents to model positive relational patterns and provide guidance on effective co-parenting strategies. This approach can help cultivate a conducive family environment that supports children’s social learning and overall development.

Incorporating parenting stress as a mediating variable in the analysis altered the direct impact of co-parenting’s impact on problem behaviors in children. The inclusion of this mediator significantly diminished the direct influence of supportive co-parenting on problem behaviors. Notably, for unsupportive co-parenting, the direct effect on problem behaviors ceased to be significant, underlining the importance of the mediating role of parenting stress. This finding underscores that parenting stress is a crucial intermediary between various co-parenting relationships and the manifestation of problem behaviors in preschool children.

The Mediating Role of Parenting Stress

Maternal parenting stress plays a mediating role in the relationship between co-parenting and preschoolers’ problem behaviors. Specifically, it partially mediates the link between supportive co-parenting and problem behaviors and fully mediates the connection between unsupportive co-parenting and problem behaviors. Precisely, as supportive co-parenting levels increase and unsupportive co-parenting decreases, maternal parenting stress diminishes. This reduction in parenting stress contributes to a decrease in preschoolers’ problem behaviors. These findings are consistent with the results of studies conducted in various cultural contexts63,64 and substantiate the process model of the determinants of parenting.30 Co-parenting is a distinctive form of social support within the family system, which can significantly influence maternal parenting stress.30 Families with higher levels of supportive co-parenting and lower levels of unsupportive co-parenting have sufficient supportive resources. Mothers within these families receive love and acceptance from their partners and valuable assistance, including parenting advice and shared parenting tasks. These resources aid mothers in addressing parenting challenges, alleviating parenting distress, and ultimately reducing parenting stress.8,30 Mothers often bear a disproportionate parenting burden within the family, rendering them more susceptible to parenting stress stemming from external pressures.

The study highlights that increased parenting stress can lead to more significant challenges in meeting the developmental needs of preschool children, a factor contributing to the rise in children’s problem behaviors.12,45,65 Furthermore, within the context of low-income families, a heightened state of maternal parenting stress tends to create a less nurturing emotional atmosphere. This tension often escalates child problem behaviors, with emotional contagion being a key mechanism in this process.66 The emotional environment influenced by maternal stress thus plays a critical role in shaping the behavioral outcomes in children. As a result, mothers who receive substantial support from their partners have a reduced parenting burden, facilitating the establishment of mutual support systems, collaborative problem-solving, and consistent parenting rules. These factors contribute to lowered maternal parenting stress levels,67 making mothers less likely to resort to harsh physical punishments. It, in turn, fosters a positive family atmosphere and reduces children’s problem behaviors.45,66

Professionals can apply this knowledge by developing and implementing programs to enhance co-parenting skills, promote positive communication, and provide strategies for stress management. Moreover, early childhood educators can play a vital role by observing children’s behavior in educational settings, identifying signs of stress or distress that may be linked to family dynamics, and providing targeted support or referrals to family counselling services. Community workers can also contribute by offering resources and services that support families in building stronger co-parenting relationships, such as family therapy or parenting classes.

The Moderating Role of Family Resilience

The findings suggest family resilience moderated the relationship between unsupportive co-parenting and parenting stress. However, it did not demonstrate a moderating effect on the association between supportive co-parenting and parenting stress. Specifically, family resilience acted as a protective factor, mitigating the adverse effects of unsupportive co-parenting on parenting stress.

In the context of family resilience’s moderating role, it was observed that negative perceptions of co-parenting and parenting stress exhibited a significant and positive correlation for both mothers with high and low levels of family resilience. This outcome is consistent with the conceptual framework of family risk and resilience and models of family well-being,42,43 supporting the idea that family resilience serves as a protective mechanism for mothers in demanding circumstances, such as situations involving unsupportive co-parenting. Family resilience effectively mitigates the detrimental effects of unsupportive co-parenting on mothers’ levels of parenting stress.

In line with the conceptual framework of family risk and resilience and models of family well-being,42,43 families with higher levels of family resilience promote positive communication and mutual support among their members. As a result, parents within these families are more inclined to support each other in parenting matters, thereby reducing instances of unsupportive co-parenting. Simultaneously, when unsupportive co-parenting levels are elevated, parents report lower levels of parenting stress, a finding corroborated by prior research.63

The study’s results indicate that family resilience is a protective factor, explicitly moderating the impact of unsupportive co-parenting on parenting stress. However, it does not significantly alter the effects of supportive co-parenting on stress levels. This finding underscores the importance of nurturing family resilience to buffer the negative consequences of unsupportive co-parenting practices for professionals such as early childhood educators and community workers. It suggests that programs and interventions to strengthen family resilience could be particularly beneficial for families experiencing high levels of unsupportive co-parenting. By focusing on building resilience, professionals can help families develop coping strategies that mitigate parenting stress, potentially leading to more positive outcomes for children. Furthermore, early childhood educators can use these insights to provide targeted support to families, emphasizing the development of resilient family dynamics. On the other hand, community workers might focus on creating supportive environments that foster family resilience, offering resources and workshops that address coping mechanisms and resilience-building techniques. Overall, the study highlights the critical role of family resilience in moderating the effects of unsupportive co-parenting on parenting stress, offering a valuable direction for interventions to support families and enhance child well-being.

Conclusion

Several limitations should be acknowledged in this study. First, the data were exclusively obtained through mothers’ reports. Although the Harman one-way test was performed in this study and verified no significant common method bias, the correlation between the variables may have been exaggerated. Therefore, to mitigate this limitation, future research efforts should consider incorporating diverse measurement techniques, such as behavioral observations or peer reports. Additionally, the relationship between co-parenting relationships, children’s problem behaviors, parenting stress, and family resilience could also be explored in the future in different cultural contexts. Secondly, it is noteworthy that all participants in this study were mothers from Shanghai, a super Tier 1 city and one of the most developed urban centers in China. As a result, the sample may only partially represent Chinese parents. Thus, to enhance the generalizability of findings, forthcoming studies should include parents from various cities to present a more comprehensive perspective on Chinese parenting experiences. Furthermore, this research adopted a cross-sectional research design, enabling the examination of relationships between variables at a single time. For a deeper understanding of how co-parenting relationships impact the developmental outcomes of preschoolers, future investigations are encouraged to employ longitudinal research methodologies, which can provide insights into the effects over time. In addition, this study focuses exclusively on the significant role of mothers in family dynamics and child-rearing. Given the crucial involvement of fathers and the characteristic participation of grandparents in Chinese cultural settings, future research should also consider the participation of fathers or other caregivers.

The current study uncovered that parenting stress mediates the association between co-parenting and children’s problem behaviors. Additionally, family resilience emerged as a pivotal moderator in the relationship between unsupportive co-parenting and children’s problem behaviors. These findings emphasize the importance of considering parenting stress and family resilience in the intricate dynamics between co-parenting and child problem behavior. The results of this investigation provide novel insights for developing potential interventions, policies and support strategies to enhance preschool children’s social adjustment.

Data Sharing Statement

The data and materials used during the current study are available from the corresponding author (Yan Li) on reasonable request.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Shanghai Normal University. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Acknowledgments

We are really grateful to the participating children, parents, and teachers.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Jingjing Zhu, Shuhui Xiang and Yan Li. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Shuhui Xiang and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal heto which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This work was supported by STI 2030-Major Projects (No. 2022ZD0209000) and the National Social Science Foundation for Youth (Grant No. 21CSH048).

Disclosure

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Lv Q, Chen H, Wang L. A review of studies on children’s problem behaviors and related parental rearing factors. J Psychol Sci. 2003;2003(01):125–127. doi:10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.2003.01.035

2. Abidin RR. Introduction to the special issue: the stresses of parenting. J Clin Child Psychol. 1990;19(4):298–301. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp1904_1

3. Bor W, McGee TR, Fagan AA. Early risk factors for adolescent antisocial behavior: an Australian longitudinal study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2004;38(5):365–372. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1614.2004.01365.x

4. Bulotsky-Shearer RJ, Fantuzzo JW. Preschool problem behaviors in classroom learning situations and literacy outcomes in kindergarten and first grade. Early Child Res Q. 2011;26(1):61–73. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2010.04.004

5. Cabrera NJ, Scott M, Fagan J, Steward-Streng N, Chien N. Coparenting and children’s school readiness: a mediational model. Fam Process. 2012;51(3):307–324. doi:10.1111/j.1545-5300.2012.01408.x

6. Camisasca E, Miragoli S, Covelli V. Dallo stress economico al malessere psicologico dei minori durante la pandemia da Covid-19: quale ruolo per il conflitto co-genitoriale e le pratiche educative autoritarie? Maltrattamento E Abuso all’Infanzia. 2021;23(1):13–27. doi:10.3280/MAL2021-001002

7. Powe F, Mallise CA, Campbell LE. A first step to supporting the coparenting relationship and reducing child behavior problems: a delphi consensus study. J Child Fam Stud. 2022;1–17. doi:10.1007/s10826-021-02090-3

8. Zhang L, Guo F, Chen Z, Yuan T. Relationship between paternal co-parenting and children’s externalizing problem behavior: the chain mediating effect of maternal parenting stress and maternal parenting self-efficacy. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2023;31(04):928–933. doi:10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2023.04.032

9. Zhao F, Wu H, Li Y, Zhang H, Hou J. The association between coparenting behavior and internalizing/externalizing problems of children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(16):10346. doi:10.3390/ijerph191610346

10. Erel O, Burman B. Interrelatedness of marital relations and parent-child relations: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 1995;118(1):108. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.108

11. Berryhill MB, Soloski KL, Durtschi JA, Adams RR. Family process: early child emotionality, parenting stress, and couple relationship quality. Pers Relat. 2016;23(1):23–41. doi:10.1111/pere.12109

12. Liu Y, Deng H, Zhang G, Liang Z, Lu Z. Association between parenting stress and child problem behaviors: the mediation effect of parenting styles. Psychol Dev Educ. 2015;31(3):319–326. doi:10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2015.03.09

13. Kim I, Dababnah S, Lee J. The influence of race and ethnicity on the relationship between family resilience and parenting stress in caregivers of children with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2020;50:650–658. doi:10.1007/s10803-019-04269-6

14. Silva ÍD, Cunha KD, Ramos EM, Pontes FAR, Silva SS. Family resilience and parenting stress in poor families. Estud Psicol. 2020;38:e190116. doi:10.1590/1982-0275202138e190116

15. Karela C, Petrogiannis K. Risk and resilience factors of divorce and young children’s emotional well-being in Greece: a correlational study. J Educ Dev Psychol. 2018;8(2):2. doi:10.5539/jedp.v8n2p68

16. Minuchin P. Families and individual development: provocations from the field of family therapy. Child Dev. 1985;56(2):289–302. doi:10.2307/1129720

17. Chen BB. The relationship between Chinese mothers’ parenting stress and sibling relationships: a moderated mediation model of maternal warmth and co-parenting. Early Child Dev Care. 2020;190(9):1350–1358. doi:10.1080/03004430.2018.1536048

18. Feinberg ME. The internal structure and ecological context of coparenting: a framework for research and intervention. Parent Sci Pract. 2003;3(2):95–131. doi:10.1207/s15327922par0302_01

19. McHale JP, Lindahl KM. Coparenting: A Conceptual and Clinical Examination of Family Systems. Washington, WAS: American Psychological Association; 2011. doi:10.1037/12328-000

20. Stright AD, Bales SS. Coparenting quality: contributions of child and parent characteristics. Fam Relat. 2003;52(3):232–240. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2003.00232.x

21. Solmeyer AR, Feinberg ME. Mother and father adjustment during early parenthood: the roles of infant temperament and co-parenting relationship quality. Infant Behav Dev. 2011;34(4):504–514. doi:10.1016/j.infbeh.2011.07.006

22. Davies PT, Woitach MJ. Children’s emotional security in the interparental relationship. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2008;17(4):269–274. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00588.x

23. Song S. Co-parenting, parenting, and preschool children’s adjustment [Doctoral dissertation]. Texas Tech University; 2020.

24. Westrupp EM, Brown S, Woolhouse H, Gartland D, Nicholson JM. Repeated early-life exposure to inter-parental conflict increases risk of preadolescent mental health problems. Eur J Pediatr. 2018;177:419–427. doi:10.1007/s00431-017-3071-0

25. Fang Y, Luo J, Boele M, Windhorst D, van Grieken A, Raat H. Parent, child, and situational factors associated with parenting stress: a systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022;1–19. doi:10.1007/s00787-022-02027-1

26. Avery AR, Tsang S, Seto EY, Duncan GE. Differences in stress and anxiety among women with and without children in the household during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health. 2021;9:688462. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.688462

27. Mak MCK, Yin L, Li M, Cheung RYH, Oon PT. The relation between parenting stress and child problem behaviors: negative parenting styles as mediator. J Child Fam Stud. 2020;29(11):2993–3003. doi:10.1007/s10826-020-01785-3

28. Han JW, Lee H. Effects of parenting stress and controlling parenting attitudes on problem behaviors of preschool children: latent growth model analysis. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2018;48(1):109–121. doi:10.4040/jkan.2018.48.1.109

29. Cherry KE, Gerstein ED, Ciciolla L. Parenting stress and children’s behavior: transactional models during Early Head Start. J Fam Psychol. 2019;33(8):916–926. doi:10.1037/fam0000574

30. Belsky J. The determinants of parenting: a process model. Child Dev. 1984;55:83–96. doi:10.2307/1129836

31. Crnic K, Low C. Everyday stresses and parenting. In: Bornstein M, editor. Handbook of Parenting Volume 5 Practical Issues in Parenting. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002:242–268.

32. Durtschi JA, Soloski KL, Kimmes J. The dyadic effects of supportive coparenting and parental stress on relationship quality across the transition to parenthood. J Marital Fam Ther. 2017;43(2):308–321. doi:10.1111/jmft.12194

33. Thullen M, Bonsall A. Co-parenting quality, parenting stress, and feeding challenges in families with a child diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2017;47(3):878–886. doi:10.1007/s10803-016-2988-x

34. Bailey SJ, Letiecq BL, Visconti K, Tucker N. Rural native and European American custodial grandparents: stressors, resources, and resilience. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2019;34:131–148. doi:10.1007/s10823-019-09372-w

35. Herbell K, Breitenstein SM, Melnyk BM, Guo J. Family resilience and flourishment: well-being among children with mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders. Res Nurs Health. 2020;43(5):465–477. doi:10.1002/nur.22066

36. Walsh F. A family resilience framework: innovative practice applications. Fam Relat. 2002;51(2):130–137. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2002.00130.x

37. Walsh F. Family resilience: a developmental systems framework. Eur J Dev Psychol. 2016;13(3):313–324. doi:10.1080/17405629.2016.1154035

38. Plumb JC. The impact of social support and family resilience on parental stress in families with a child diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Pennsylvania Scholarly Commons; 2011. Available from: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations_sp2/14.

39. Lazarus RS. From psychological stress to the emotions: a history of changing outlooks. Annu Rev Psychol. 1993;44(1):1–21. doi:10.1146/annurev.ps.44.020193.000245

40. Hill R. Families Under Stress: Adjustment to the Crises of War Separation and Return. New York, NY: Harper; 1949. doi:10.2307/2572778

41. Li Y, Zhao Y, Zhang J, Lou F, Cao F. Psychometric properties of the shortened Chinese version of the family resilience assessment scale. J Child Fam Stud. 2016;25(9):2710–2717. doi:10.1007/s10826-016-0432-7

42. Newland LA. Family well-being, parenting, and child well-being: pathways to healthy adjustment. Clin Psychol. 2015;19(1):3–14. doi:10.1111/cp.12059

43. Prime H, Wade M, Browne DT. Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am Psychol. 2020;75(5):631. doi:10.1037/amp0000660

44. Ji Y, Wu X, Sun S, He G. Unequal care, unequal work: toward a more comprehensive understanding of gender inequality in post-reform urban China. Sex Roles. 2017;77(11):765–778. doi:10.1007/s11199-017-0751-1

45. Liu L, Wang M. Parental parenting stress and internalizing problem behavior in children: mediating of corporal punishment. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2018;26(01):63–68. doi:10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2018.01.015

46. Hong X, Liu Q. Parenting stress, social support and parenting self-efficacy in Chinese families: does the number of children matter? Early Child Dev Care. 2021;191(14):2269–2280. doi:10.1080/03004430.2019.1702036

47. Luo Y, Qi M, Huntsinger CS, Zhang Q, Xuan X, Wang Y. Grandparent involvement and preschoolers’ social adjustment in Chinese three-generation families: examining moderating and mediating effects. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;114:105057. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105057

48. Chen BB. Chinese adolescents’ sibling conflicts: links with maternal involvement in sibling relationships and coparenting. J Res Adolesc. 2019;29(3):752–762. doi:10.1111/jora.12413

49. Abidin R, Flens JR, Austin WG. The Parenting Stress Index. In: Archer RP, editor. Forensic Uses of Clinical Assessment Instruments. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2006:297–328. doi:10.1037/t02445-000

50. Geng L, Ke X, Xue Q, et al. Maternal parenting stress and related factors in mothers of 6-month infants. Chin Pediatr Integr Tradit West Med. 2008;27(6):457–459.

51. Du Y, Kou J, Coghill D. The validity, reliability and normative scores of the parent, teacher and self-report versions of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire in China. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Ment Health. 2008;2(1):1–15. doi:10.1186/1753-2000-2-8

52. Goodman R. Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(11):1337–1345. doi:10.1097/00004583-200111000-00015

53. Zhu J, Ooi LL, Li Y, et al. Concomitants and outcomes of anxiety in Chinese kindergarteners: a one-year longitudinal study. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2017;52:24–33. doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2017.06.006

54. Sixbey MT. Development of the Family Resilience Assessment Scale to Identify Family Resilience Constructs. University of Florida; 2005.

55. Huang H, Wang X. The effect of family socioeconomic status on migrant preschool children’s problem behaviors: the chain mediating role of family resilience and child-parent relationship. J Psychol Sci. 2022;45(2):315–322.

56. Hayes AF. PROCESS: a versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling [White paper]. Available from http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf.

57. Zhou H, Long L. Statistical remedies for common method biases. Adv Psychol Sci. 2004;2004(06):942–950. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1671-3710.2004.06.018

58. Aiken LS, West SG, Reno RR. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. New York, NY: SAGE; 1991.

59. Wang Z, Cheng N. Co-parenting and the influence on child adjustment. Advances in Psychological Science. 2014;22(6):889–901. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1042.2014.00889

60. Akers RL, Jennings WG. Social learning theory. In: Piquero AR, editor. Handbook of Criminological Theory. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell; 2015:230–240. doi:10.1002/9781118512449.ch12

61. Belsky J. Early human experience: a family perspective. Dev Psychol. 1981;17(1):3. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.17.1.3

62. Rosencrans M, McIntyre LL. Coparenting and child outcomes in families of children previously identified with developmental delay. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2020;125(2):109–124. doi:10.1352/1944-7558-125.2.109

63. Camisasca E, Miragoli S, Di Blasio P, Feinberg M. Pathways among negative co-parenting, parenting stress, authoritarian parenting style, and child adjustment: the emotional dysregulation driven model. J Child Fam Stud. 2022;31(11):3085–3096. doi:10.1007/s10826-022-02408-9

64. Choi MK, Doh HS, Kim MJ, Shin N. Investigating the relationship among co-parenting, maternal parenting stress, and preschoolers’ anxiety and hyperactivity. J Fam Better Life. 2013;31(2):25–39. doi:10.7466/JKHMA.2013.31.2.025

65. Tsotsi S, Broekman BF, Shek LP, et al. Maternal parenting stress, child exuberance, and preschoolers’ behavior problems. Child Dev. 2019;90(1):136–146. doi:10.1111/cdev.13180

66. Denham SA, Mitchell-Copeland J, Strandberg K, Auerbach S, Blair K. Parental contributions to preschoolers’ emotional competence: direct and indirect effects. Motiv Emot. 1997;21:65–86. doi:10.1023/A:1024426431247

67. Fagan J, Lee Y. Longitudinal associations among fathers’ perception of coparenting, partner relationship quality, and paternal stress during early childhood. Fam Process. 2014;53(1):80–96. doi:10.1111/famp.12055

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.