Back to Journals » Advances in Medical Education and Practice » Volume 14

Mentoring the Wellbeing of Specialist Pediatric Palliative Care Medical and Nursing Trainees: The Quality of Care Collaborative Australia

Authors Slater PJ , Herbert AR

Received 11 October 2022

Accepted for publication 7 February 2023

Published 3 March 2023 Volume 2023:14 Pages 183—194

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S393052

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Md Anwarul Azim Majumder

Penelope J Slater,1 Anthony R Herbert2,3

1Oncology Services Group, Queensland Children’s Hospital, Children’s Health Queensland Hospital and Health Service, Brisbane, QLD, Australia; 2Paediatric Palliative Care Service, Queensland Children’s Hospital, Children’s Health Queensland Hospital and Health Service, Brisbane, QLD, Australia; 3Centre for Children’s Health Research, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Correspondence: Penelope J Slater, Oncology Services Group Level 12b, Queensland Children’s Hospital, Children’s Health Queensland Hospital and Health Service, 501 Stanley St, South Brisbane, QLD, 4101, Australia, Email [email protected]

Background: The Quality of Care Collaborative Australia (QuoCCA), working across 6 tertiary centers throughout Australia, builds capability in the generalist and specialist pediatric palliative care (PPC) workforce, by providing education in metropolitan and regional areas. As part of the education and mentoring framework, Medical Fellows and Nurse Practitioner Candidates (trainees) were funded by QuoCCA at four tertiary hospitals throughout Australia.

Objective: This study explores the perspectives and experiences of clinicians who had occupied the QuoCCA Medical Fellow and Nurse Practitioner trainee positions in the specialised area of PPC at Queensland Children’s Hospital, Brisbane, to identify the ways in which they were supported and mentored to maintain their wellbeing and facilitate sustainable practice.

Methods: Discovery Interview methodology was used to collect detailed experiences of 11 Medical Fellows and Nurse Practitioner candidates/trainees employed by QuoCCA from 2016 to 2022.

Results: The trainees were mentored by their colleagues and team leaders to overcome challenges of learning a new service, getting to know the families and building their competence and confidence in providing care and being on call. Trainees experienced mentorship and role modelling of self-care and team care that promoted wellbeing and sustainable practice. Group supervision provided dedicated time for reflection as a team and development of individual and team wellbeing strategies. The trainees also found it rewarding to support clinicians in other hospitals and regional teams that cared for palliative patients. The trainee roles provided the opportunity to learn a new service and broaden career horizons as well as establish wellbeing practices that could be transferred to other areas.

Conclusion: Collegial interdisciplinary mentoring, with the team learning together and caring for each other along common goals, contributed immensely to the wellbeing of the trainees as they developed effective strategies to ensure their sustainability in caring for PPC patients and families.

Keywords: palliative care, wellbeing, mentoring, specialist

Introduction

Even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, medical and nursing staff were at higher risk than the general population of work-related stress, burnout and mental illness, mostly related to higher demands (in quality and complexity) in an environment of decreasing resources.1 The pandemic has compounded those issues and risks of trauma and suicide are of great concern.2

This concern has been acknowledged by many of the professional associations in Australia, including the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons (RACS)3 and the Royal Australasian College of Physicians (RACP), who actively promoted wellbeing resources.4 Palliative Care Australia developed a comprehensive guide to self care with the specific aim of preventing burnout and building resilience for all staff who provided palliative care. They quoted Dr Rachel Naomi Remen:

The expectation that we can be immersed in suffering and loss daily, and not be touched by it, is as unrealistic as expecting to be able to walk through water without getting wet.5

The Quality of Care Collaborative Australia (QuoCCA), with its remit to provide national pediatric palliative care (PPC) education since 2015, heard the concerns of healthcare professionals to be able to maintain their wellbeing while providing PPC. The most requested education topics were related to staff support/coping, self care, clinical debriefing, professional boundaries and grief / bereavement.6 In an evaluation of the longer term outcomes of the education provision, staff reported the emotional toll of being involved in the PPC cases, highlighting the importance of ongoing support for sustainable practice through the tertiary team and local wellbeing strategies.7 A major theme in interviews with health professionals and educators involved in QuoCCA education was sustaining wellbeing, including emotional wellbeing, finding meaning and purpose in the work and finding a supportive tribe.8

The awareness of the concerns of health professionals delivering PPC motivated the QuoCCA Project to include strategies to support wellbeing and sustainability, in addition to clinical skills, in the QuoCCA education and mentoring framework for Medical Fellows (MF) and Nurse Practitioner (NP) trainees. These positions were funded at four hospitals (Queensland Children’s Hospital, Brisbane (QCH); Sydney Children’s Hospital, Randwick; John Hunter Children’s Hospital, Newcastle and Women’s and Children’s Network, Adelaide).

Mentoring of general medical trainees is widely practiced and beneficial at varying career stages.9 One clear advantage to mentoring is that it can facilitate development in aspects not often included in formal training, such as wellbeing, life balance, empathy and relationship management.10,11 Mentoring has also been found to improve confidence and stress management, encourage critical reflection, and improve connections with colleagues through networking.9,11 Nurse mentoring programs also have the potential to sustainably strengthen the nursing workforce.12 A review of 69 nursing mentoring programs from 11 countries found that mentoring, as well as improving clinical skills, provided learnings around emotional support, socialising the mentees into the workplace, building trust, providing career guidance, and improving networks.12 Nurse mentoring in Australia is seen as a way of valuing multigenerational staff; interacting with them in a meaningful way so they feel supported and engaged.13

Although these and other studies showed the opportunities to promote wellbeing through mentoring, it was unknown how this could be applied in the context of the specialised area of PPC through the QuoCCA education and mentoring framework.14 The purpose of this study was to explore the perspectives and experiences of clinicians who had occupied the QuoCCA MF and NP trainee positions in the specialised area of PPC to identify the ways in which they were supported and mentored to maintain their wellbeing and facilitate sustainable practice.

Methods

Research Instrument

This study utilized Discovery Interview (DI) methodology to explore the perspectives of MF and NP candidates (or trainees) employed by QuoCCA working in the QCH specialist tertiary Paediatric Palliative Care Service (PPCS).

DI methodology was developed by the National Health Service in the United Kingdom as a service improvement tool and patient involvement mechanism for progressing patient-centered services.15–17 Discovery Interviews consisted of a one to one, open interview technique that enabled the collection of detailed experiences of participants with the content driven by the interviewees.15,17 This methodology had been implemented in the QCH oncology service since 2012 and benefits had been demonstrated for exploring the experience of both consumers and staff.18 DIs allowed the interviewee to freely relay their experience, discussing aspects that were important to them, rather than being steered by questions posed by an interviewer. The methodology thus allowed all the aspects of wellbeing to be explored for the purposes of the study aim.

Research Procedure and Samples

All the past Queensland based QuoCCA MF and NP trainees were contacted by email or in person to participate in interviews. The participants were self-selected as per convenience sampling related to their availability and accessibility for an interview as trainees moved back to their substantive position or on to different hospitals.

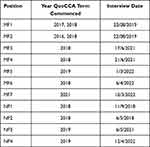

DIs were undertaken between September 2018 and April 2022 with 7 MFs and 4 NPs trainees who had completed their term of employment with QuoCCA. Their resulting consent and interview occurred at differing timeframes after the completion of their QuoCCA role (Table 1). Note that some completed more than one term in the QuoCCA trainee positions.

All interviews were conducted by the QuoCCA National Project Advisor (PJS), who was trained in undertaking Discovery Interviews, in a meeting room at the participant’s workplace or via phone/videoconference. Participation was voluntary and the interviewee was assured they could stop the interview at any time. The interviewee was taken through a participant information sheet and consent form, which was signed and witnessed, and instructions given about how to revoke an interview from the pool. The participants were informed both in writing and verbally about how the data would be used in the study, including publication of de-identified responses.

A “spine” guided the interviewee through their story based on key stages of their experience of the service (Box 1).17 The spine was based on the spine developed for the Oncology Services Group by the DI interviewers and trainers, reflecting overall stages of care, treatment and outcomes, expressed in plain English and not leading the interviewee into specific topics. The interviewer could use this spine as a prompt to facilitate the interviewee to tell their story and talk about whatever they felt was important in those areas in the journey of being a health professional in PPC. Clarifying questions were kept open and did not guide the interviewee down any particular path.

|

Box 1 QuoCCA Discovery Interview Spine for Health Professionals |

The interview duration was determined by the interviewee. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed by a professional transcription service and de-identified (for patient, family, clinicians and location).

The reporting for this qualitative study was guided by the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies (COREQ).19 To align with the intention of the DI methodology an inductive thematic analysis was conducted.20 This methodology ensured the voice and experience of individual participants was retained while simultaneously allowing for collective themes. Transcriptions were analyzed drawing on the phases described by Braun and Clarke: generating initial codes through immersion in the data; sorting codes into sub themes; refinement of themes in collaboration with the co-author; and finalizing a thematic map of the data.21 Microsoft Excel was used to record and count the results under themes and sub themes with associated quotes, and to arrange the records under appropriate sub themes as they emerged.

The protocol for this project was approved by the Children’ Health Queensland Human Research and Ethics Committee (HREC/16/QRCH/55).

Results

QuoCCA employed 31 MFs throughout Australia to June 2022; 15 being based in Queensland. Most of these were full time and most had 6 month terms (although some part time fellows had 12 month terms). Five NP candidates were employed in Queensland. Most were employed part time at 0.4 to 0.6 full time equivalent for terms varying from 6–12 months (one was 3 months).

The source and subsequent positions for each trainee were varied: the Medical Fellows were mostly Registrars (that is, training doctors) from QCH or other hospitals. Three of them were specifically training in PPC, while others were wanting to gain experience and exposure to PPC as they undertook other specialty training in pediatrics (eg emergency, oncology, general pediatrics). The Nurse Practitioner trainees came from other departments within QCH or other hospitals, where they were Nurse Practitioners or Clinical Nurse Consultants. They had various levels of previous experience in PPC. One of them subsequently transitioned from working in the Emergency Department to the PPCS in a permanent position.

Seven MFs (two males and five females) and four NP candidates (all females) who had been employed in Queensland were interviewed over the period 2018 to 2022 (Table 1). As there was only one or two MFs or NPs employed at a time, the collection of the 11 interviews for this study took place over several years (Table 1). The average interview time was 32 minutes, ranging from 16 to 59 minutes. The trainees’ experiences went well beyond PPC clinical education, as they became immersed in the nature of care provided by the service and found various means as individuals and with the team, to sustain their practice.

There were several themes that arose from the interviews: challenges of the role as the trainee commenced, self-care, team care, caring for families as a team, group and individual supervision, supporting colleagues external to the team, and career insights and planning.

Challenges of the Role

The majority of the trainees had come from another service area, either generalist or specialist, and now had to learn the skills associated with PPC.

It had taken me a while to... get used to it – I almost felt like a student. Going from being very confident to not, and thinking, am I actually contributing? Feeling like I know nothing. What am I doing? … But then to remind myself; no, this is why I’m doing it. NP2

Working part time could be a challenge; one interviewee found it took a good six months for them to find their feet and contribute. It was also difficult to finish things off and find continuity from week to week.

So having that extra time … is really valuable, because it means I feel like now I can actually contribute and can build on those skills that I’m learning. NP2

Getting to know the families in the service was a priority. The families had expectations that the clinician they were interacting with would know their child, even if they had not been in contact with the service for some time.

As a newbie and trying to learn the intricacies of each family, let alone what’s wrong with the child … feeling inadequate or that I don’t have that knowledge, which is hard. NP2

Being on call was a particular challenge for those new to the area. The trainee was concerned that they may not know the background of the child to assess them appropriately, especially if it was an emergency situation.

Whether or not you were going to get a phone call in the middle of the night … that was a bit confronting for me. Especially when I didn’t know the families or I hadn’t actually done that process before. But I still think it’s a privilege to be involved with the families during that time. NP4

One trainee talked about doing home visits where you had never met the family and the family had been working with another team member.

I don’t think it was the ideal, probably for the families as well, in that they were meeting people that they had never met in a very vulnerable time … so I did my best to engage with families and provide the support … that’s tricky if you’ve been liaising or having deep conversations with one team member. NP3

At the start, the trainees needed to develop their own strategies to communicate with families, to introduce the concept of palliative care and have conversations around death and dying. Communication with families was one of the most requested topics at QuoCCA education, and evaluated well, as it gave a much needed level of confidence to clinicians.

I was probably a bit nervous at the start … I didn’t think I had the right language for talking about death and dying … and the [team] were all very supportive in the fact that you let [the family] choose the words that they want to use …. And you just mirror them back, so that’s a much less confronting way for families to hear it. MF5

Self Care

The interviewees commented on strategies that they had implemented to support themselves and maximise the opportunity they had in their roles. This was underpinned by a good level of personal reflection, self-awareness and the ability to reflect on the nature of the work.

You’re dealing with suffering and distress and death and then it makes you look at your own life, I guess. It’s hard not to get affected by looking after and trying to relieve suffering. And it may be … obvious tangible suffering but then there’s the global suffering that happens, that can be difficult. MF1

Practicing and normalising self care was important to sustain the interviewees, along with support from their team colleagues.

I have my own self-care plan … And some weeks are harder than others. So you can get a run … looking after a family … that was a particularly difficult case… So looking out for each other and being able to talk about that and not feel like you’re being silly. It’s important. NP2

Team Care

Trainees were impacted when providing care to families in the context of suffering, distress and death. Partnering with a senior clinician provided a foundation for their support.

Working alongside someone who’s had many, many years’ experience … I definitely feel very well supported. NP2

The whole team had a valuable role in providing a good learning environment for trainees. The mode of operation was interdisciplinary, with collaboration and mutual respect. The trainees benefited from this team approach to care, which gave them an avenue for discussion and supportive peer review.

Having two senior medical fellows is really helpful from a support point of view, in that you would have the other person to talk to … also from a practical point of view, having to prescribe. MF5

It would be very rare that you would ever meet a family on your own. You would always have the support of …one of the other consultants plus or minus a nurse. MF5

Trainees found it draining when there was ongoing challenge without a good outcome for a family. Support and guidance for moral distress was important when providing care for a child with a low quality of life. Informal support for trainees was provided through discussions with the Consultant and other team members, and with the whole team during regular meetings. Difficult cases affected the whole team and they could look out for each other and discuss their perspectives. It was important for the team members to be self-aware about how the work was impacting their interactions with families and other members of the team.

Being a small team which worked quite efficiently, you sort of knew each other, and were able to work in a quite supportive environment. I think the availability of having a multidisciplinary team and quite senior people around, experienced, empathetic, and because I think the compassion fatigue was quite a prominent issue. MF4

One example of this was when one trainee was caring for a long term challenging family, and was offered relief from another team member to enable them to have time to refresh and rejuvenate.

With the high stress context of the team, dysfunctional moments could arise, and one trainee suggested that people be mindful of the energy they were bringing to the team, as emotional work required emotional intelligence.

What’s really great about pall care is that I think they recognise that those small arguments are often reflective of something much bigger. And so instead of just having a small argument about the coffee cups, you’d say ‘Actually, I’m reflecting more, I think I’m really stressed about that interaction that I had with this parent and I probably just focused that onto something that I can control, like that coffee cup.’ And that requires a lot more emotional intelligence that the average punter. MF5

You have to be in control of your own emotions and know what you’re bringing, like your preconceived ideas or if you’ve had a bad morning …. Make sure you’re being mindful about … what energy you’re bringing to the patients and the team, because it can cause some issues if you’re not in control of yourself. MF5

The team provided the support for the trainees that reinforced the meaning and purpose of their roles.

It’s always the people you work with, isn’t it, that really are the immense support and I think it’s been … such a lovely team. It’s a team that is focused just for one goal really, and that is to give the person dying and their family the quality of life and the experience they deserve at the end. MF1

Caring for Families

Trainees found meaning in their work in being able to support and care for families, from their first introduction to the palliative care service to supporting them after the death of the child.

That ability to support people is an amazing privilege. It was a very satisfying family to support because it was really complicated, very difficult. But you could really achieve things. MF3

The family was met and supported as a team in home visits and consultations, using the different strengths and skill sets of the team. The common goal was to improve quality of life and provide a good experience for the family in meeting their needs. In this context, the trainees could also work through the benefits of ongoing treatment with the families and were supported by the team to discuss any moral distress.

It’s a point of moral distress amongst clinicians about providing high level support for a child who really has a very low quality of life, but you always see them when they’re at their worst. And the families don’t, and they have different perspectives and they follow this child and they’re very invested in it …. That’s complicated and half your care isn’t for the child … much more the family mental health at that time. MF3

I had a couple of cancer patients who in the beginning were really not accepting and I kind of learned some techniques to straddle that …. Them seeing we were doing everything we could to keep that child at home and happy to try new therapies, knowing fully well they were completely futile. They weren’t futile for the family… the fact that we were trying to do that was meaningful for the family. They felt like they had done everything and I think that is really important for families. MF5

Supervision

The provision of formal group supervision allowed dedicated time for the team to reflect on what went well and not so well and do some team planning. It enabled the trainees to be vulnerable and talk about strategies to deal with complex trauma, feel heard and refresh with the team. Team members had opportunities to reflect on self and team care in the sessions. Regular death reviews by the team were also useful in providing a space for closure, especially for patients they had known for a long time, and to work through their experience.

They also had sessions and workshops on how to deal with stress and compassion fatigue … how different people deal with complex trauma is different and it’s sometimes hard to keep the human away from the cold personality of just being a medic, because we are intertwined as human beings, sometimes it gets into us and having a forum to talk about it in a non-judgemental way was quite good. MF4

… having more formal supervision, I thought was very valuable and I did learn a lot and helped that dedicated time of reflection and teamwork and trying to plan and move forward … that bit of self care and just thinking around the way that you then process things slightly differently … how we’re stressed and what our different reactions are and how we outwardly show that … talking around understanding some of the dynamics at times … you’re also then learning from them and that indirectly helps you through their reflection. MF6

We did a formal supervision with a clinical psychologist … we just like brainstormed all the things that go well in palliative care, things that don’t go well... then talked about it and I really loved that … it was dedicated time just to reflect and that is almost unheard of in any other clinical space … and it made people feel heard and listened to in a non-threatening environment … palliative care needs formalised ongoing supervision because they deal with too much trauma to not have it. And even if they think they don’t need it, that probably means they need it even more. MF5

Trainees suggested regular individual support from a psychologist and formal clinical debriefing.

If you had identified two or three individuals who might be going through a hard period of time and if there was a psychologist who could spend half an hour, twenty minutes on a one-to -one basis, because it’s harder to open up or debrief on things when you’re sitting in a group of twenty. MF4

Supporting External Colleagues

As the trainees were supported in their roles, they also were able to support colleagues external to the team, including those within the hospital, statewide regional teams and the national QuoCCA team.

But palliative care is also there to support the clinicians because they were often having a lot of emotional distress with the death … we were doing psychological interventions on the clinicians, just by listening to them and hearing about how hard it was and highlighting all the things they’d done really well and supporting them through the death process... because it doesn’t happen very often. MF5

The trainees were involved in meaningful and collaborative conversations with other units within the hospital as PPCS collaborated in the care of the patient and may see the family in between consultations with the specific clinical team.

Palliative care is very good at not being negative about other units …. And that requires a lack of ego … acknowledge how much knowledge and skill each individual team has and what they bring and then, how we can work together as a team to bring the best outcome for the patient … we’re very happy to have collaborative conversations. So there’s no blaming, there’s no ‘You should have done this’ … just cut all that ego out of it and just say, ‘Where are we now? How can we best help this patient’? MF5

QuoCCA trainees could support the regional team with emotional distress, by listening to their experience and providing or suggesting psychological interventions. Trainees found it rewarding to support regional teams, who were always grateful. This built trust and rapport between regional and tertiary teams, cemented relationships, and improved referrals. There was a good sense of comradery and teamwork even if the support was only provided through phone or email.

Career Planning

QuoCCA gave the opportunity to trainees to be immersed in a different service and expand their horizons regarding their future work in health care. One trainee realised that they wanted to come back and do further training in PPC as they found the work enjoyable and rewarding.

Palliative care has always been one of my main interests. And I saw the opportunity to work through QuoCCA project to increase my knowledge of the non-oncology palliative care conditions across the service... so it was an opportunity to broaden my knowledge base and to see the processes from a tertiary perspective. NP3

So it really cemented …. that I wanted to do paeds pall care training … you’ve only got one chance to make such a small different on the long term … that has inspired me to want to make … a terrible situation better as we can so that those that are left behind can continue living. MF6

Overall the feedback on the trainees’ experience were positive.

I think it was a good opportunity … even if it’s not the area that you choose to work in … we deal with people in all different stages and so that was good experience … Sometimes going and doing something else to expand your horizons a little bit, and get some new skills, but also insight into what other things you can do with your job… NP4

The experience of providing PPC encouraged some trainees to make the best of their life, including an appropriate balance of their career and family, and ensuring they improved the sustainability and satisfaction from their career.

Discussion

This study gave medical and nursing trainees in PPC an opportunity to reflect on the support provided for their wellbeing within the QuoCCA education and mentoring framework. This was shared in relation to their experience of the various stages of caring for children with life limiting illnesses and their families.

Mentoring has been shown, not only to have a positive impact on quality of care outcomes, but also clinician wellbeing, self-confidence, empowerment, career advancement, workplace culture, staff engagement and retention in high, medium and low income countries.22–24

In critical care nurses, mentoring enabled the development of autonomy and independence, resulting in personal and professional growth and increased self-esteem and confidence in mentees.25 Mentoring as part of a resilience intervention for forensic nurses expanded networks and career development opportunities, increased confidence and competence at problem-solving, and built higher levels of resilience, well-being, and self-confidence.26

Mentoring programs are increasingly used in medical schools as part of the curriculum and show similar benefits to those in healthcare settings in the management of stressful situations and life balance.27,28

A review of the relationship between mentoring and doctor’s health and wellbeing found that team relationships, networking and wellbeing (including confidence and stress management) were all positively impacted through mentoring.29 Wellbeing support for staff in specialised services through mentoring also has a flow on effect of improved relationships with all stakeholders and better quality of care.11 In particular, individualised mentoring, interdisciplinary education and shadowing of the clinical practice of experienced staff develops enduring interdisciplinary relationships.30

A Caring Mentoring Model introduced to nurses in Pakistan resulted in senior nurses forming a “meaningful and reflective relationship with the nurses beyond the cognitive and interactive understanding to improve employee experience leading to enhanced patient experience”.31 Through a sense of belonging, pastoral care and support for personal and professional development, mentoring can provide a way to prevent burnout and compassion fatigue.13

A randomised controlled study of junior doctors showed that mentoring provided them with a supportive community that helped them professionally and well as personally.10,32 It positively impacted stress, morale, job satisfaction and wellbeing.32 Belonging to a team and connecting with others in the workplace addresses a core need for team members and makes them feel valued and supported.33

One of the components that ensures joy at work proposed by the Institute of Healthcare Improvement was teamwork and camaraderie.34 They suggested psychological personal protective equipment for healthcare including pairing workers together in a buddy system and making peer support services available.35 An education and mentoring framework that proactively supports wellbeing through team cohesion and collaboration empowers these protective features in the workplace.

MF and NP trainees in PPC in this study reported that the QuoCCA education and mentoring framework supported the development of sustainable practice through self and team care, working together as a team to support families and regional health practitioners, and career planning. This positive experience of mentoring arose from supportive leadership and a collaborative interdisciplinary team that focused on shared principles of family centered holistic care. Team based mentoring in QuoCCA was found to be valuable in supporting the trainees’ wellbeing, which was strengthened further through group supervision. Although some studies have found challenges of professional boundaries related to NP roles in the context of medical mentorship,36 this study showed a synergistic relationship between the NP and MF trainees as well as medical team members, which underpinned their confidence and support in their new role.

Challenges experienced by trainees were addressed by the team as they collaboratively mentored each new clinician to adopt the skills required, provided information on families in their care, had handovers to discuss family situations, and were available for back up and support for on-call work. The standard practice of the team was to prioritise self and team care, supporting each other and the families together, and role modelling positive wellbeing strategies for the trainees to encourage sustainability. Formal individual and group supervision was also valuable in providing avenues for the team to discuss any issues, celebrate successes and plan for the next few months. The QuoCCA trainees in turn mentored the wellbeing of general health practitioners in regional areas.8

Career Development

The QuoCCA positions fostered the interest of trainees who wished to pursue PPC as a career path or have PPC as a special interest in their career. Mentoring programs can have a large component of career pathway support and assist the recruitment and retention of trainees to under-subscribed specialities.27 Mentored trainees report higher confidence and job satisfaction, as well as better networks and career progression.30,37

As the wellbeing and support strategies developed in the QuoCCA trainee positions became business as usual, these roles became more attractive, encouraging recruitment, sustainability and retention. Specialised providers of PPC, and the medical and nursing professions, can only benefit from a wellbeing emphasis as provided in the QuoCCA Project.

Implications and Conclusion

Supporting the wellbeing of clinicians should be multi-faceted and multi-level to address the differing needs of individuals and teams.38 Self care is an important foundation and should be supported along with team and organisational level strategies to facilitate resilience and long term sustainability. It is important that organisational leadership shows that it is listening and being responsive to the needs of healthcare workers’ wellbeing, especially in challenging areas.39,40

As the QuoCCA trainees relayed their experience, they showed the value of mentoring from their colleagues and leaders to promote wellbeing. Wellbeing was not just an individual responsibility, but was role modelled through the care and mentoring provided to new clinicians by the whole team, as they supported trainees to be comfortable and confident in their care of children and families. The trainees experienced the prioritisation and support of individual and team wellbeing as business as usual, enabling them to fully engage in the care of patients and families and the meaning and satisfaction arising from their work.

This study has shown the value of mentoring to support the wellbeing of trainees for a specialist service. A standard program of work has been recommended for the QuoCCA education and mentoring framework.14 This should include strategies for personal wellbeing, professional issues, life balance, management of distress, networking and career counselling.41

The mentoring of the QuoCCA MF and NP trainee roles supported self and team care, and promoted the wellbeing, professional and personal development and career progression of the trainees. Collegial interdisciplinary mentoring, with the team learning together and caring for each other, contributed immensely to the wellbeing of the trainees.

Limitations and Future Research

This study shares authentic experiences of health professionals who were working in medical and nursing trainee specialist positions in PPC. The richness of these voices informs future mentoring approaches within the PPCS and QuoCCA. A limitation of this study saw recruitment of interviews limited to one Australian state. Greater diversity of experiences would be captured through inclusion of health professionals that represent the particular nuances of each Australian state.

Recruitment to the interview process was low, which reflected low numbers of PPC specialist trainee positions generally, but also funding and researcher capacity as QuoCCA funding mostly covered education activities. Thus the research was conducted over a number of years. The DI methodology does not require a specific sampling regime, as each interview is a rich source of information as the health professional tells their unique story.

Recruitment was interrupted by the ending of the 3-year phases of funding, for example, the 2017 recruitment was followed by a brief gap in funding. It is also acknowledged that the study period spanned the COVID pandemic, which impacted on the background wellbeing of all participants. However, children’s health services and particularly PPC services across Australia were not significantly impacted by the pandemic other than having reduced staffing during peak infection periods. In Queensland, the greatest impact of COVID on staffing commenced in 2022 after the employment term of most of the trainees interviewed.

This study described the wellbeing support experienced by clinicians training in PPC. Future research should examine a quantitative measure of wellbeing and retention in clinicians through their journey with the PPC team.

Acknowledgments

Gratitude goes to the medical and nursing staff in Queensland who provided their time to share extensive insights in interviews related to their experience with QuoCCA education and mentoring for this study. Thank you to all the members of the QCH Paediatric Palliative Care Service for supporting their colleagues that were new to the service. This study was guided through discussions with the project leads throughout Australia for the Quality of Care Collaborative Australia, particularly Dr Sharon Ryan and Dr Susan Trethewie.

Funding

The QuoCCA Project was undertaken through funding from the Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care provided from National Palliative Care Projects operating under the Chronic Disease Prevention and Service Improvement Fund, commencing with grant funding round H1314G012.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Kinman G, Teoh K. What Could Make a Difference to the Mental Health of UK Doctors? A Review of the Research Evidence. Technical Report. Kent: Society of Occupational Medicine & The Louise Tebboth Foundation; 2018. Available from: https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/24540/.

2. Kinman G, Teoh K, Harriss A. Supporting the well-being of healthcare workers during and after COVID-19. Occup Med. 2020;70(5):294–296. doi:10.1093/occmed/kqaa096

3. Surgeon wellbeing. [homepage on the Internet]. Melbourne: royal Australasian College of Surgeons. Available from: https://www.surgeons.org/en/about-racs/surgeons-wellbeing.

4. Wellbeing. [homepage on the Internet]. Sydney: royal Australasian College of Physicians; 2022. Available from: https://www.racp.edu.au/fellows/wellbeing.

5. Self Care Matters. [homepage on the Internet]. Canberra: palliative Care Australia; 2022. Available from: https://palliativecare.org.au/resource/resources-self-care-matters/.

6. Slater PJ, Herbert AR, Baggio SJ, et al. Evaluating the impact of national education in pediatric palliative care: the Quality of Care Collaborative Australia. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2018;9:927–941. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S180526

7. Slater PJ, Osborne CJ, Herbert AR. Ongoing value and practice improvement outcomes from pediatric palliative care education: the Quality of Care Collaborative Australia. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2021;12:1189–1198. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S334872

8. Donovan LA, Slater PJ, Baggio SJ, McLarty AM, Herbert AR. Perspectives of health professionals and educators on the outcomes of a national education project in pediatric palliative care: the Quality of Care Collaborative Australia. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2019;10:949–958. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S219721

9. Taherian K, Shekarchian M. Mentoring for doctors. Do its benefits outweigh its disadvantages? Med Teach. 2008;30:e95–e99. doi:10.1080/01421590801929968

10. Filho FLL, de Azevedo FVA, Augusto KL, de Oliveira Silveira HS, da Costa FAM, Alves KPB. Mentoring experience in medical residency: challenges and experiences. Rev Bras Educ Med. 2021;45(3):e0131. doi:10.1590/1981-5271v45.30-20210082.ING

11. Wilson G, Larkin V, Redfern N, Stewart J, Steven A. Exploring the relationship between mentoring and doctors’ health and wellbeing: a narrative review. J R Soc Med. 2017;110(5):188–197. doi:10.1177/0141076817700848

12. Hoover J, Koon AD, Rosser EN, Rao KD. Mentoring the working nurse: a scoping review. Hum Resour Health. 2020;18(1):52. doi:10.1186/s12960-020-00491-x

13. Goodyear C. Supporting successful mentoring. Nurs Manag. 2018;49–53. doi:10.1097/01.NUMA.0000531173.00718.06

14. Slater PJ, Herbert AR. Education and mentoring of specialist pediatric palliative care medical and nursing trainees: the Quality of Care Collaborative Australia. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2023, Jan 26;14:43–60 doi:10.2147/AMEP.S393051.

15. Wilcock PM, Stewart Brown GC, Bateson J, Carver J, Machin S. Using patient stories to inspire quality improvement within the NHS modernization agency collaborative programmes. J Clin Nurs. 2003;12:422–430.

16. Bridges J, Gray W, Box G, Machin S. Discovery interviews: a mechanism for user involvement. Int J Older People Nurs. 2008;3:206–210.

17. NHS I. Learning from Patient and Carer Experience. A Guide to Using Discovery Interviews to Improve Care. Leicester, UK: NHS Modernisation Agency; 2009.

18. Slater PJ, Philpot SP. Telling the story of childhood cancer: an evaluation of the discovery interview methodology conducted within the Queensland Children’s Cancer Centre. Patient Intell. 2016;2016:39–46.

19. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–357.

20. Cruickshank M, Wainohu D, Stevens H, Winskill R, Paliadelis P. Implementing family-centred care: an exploration of the beliefs and practices of paediatric nurses. Aust J Adv Nurs. 2005;23:31–36.

21. Braun V, Clarke V, Terry G. Thematic analysis. Qual Res Clin Health Psychol. 2014;24:95–114.

22. Abdullah G, Rossy D, Ploeg J, Davies K, Higuchi SL, Stacey D. Measuring the effectiveness of mentoring as a knowledge translation intervention for implementing empirical evidence: a systematic review. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2014;11(5):284–300.

23. Schwerdtle P, Morphet J, Hall H. A scoping review of mentorship of health personnel to improve the quality of care in low and middle-income countries. Glob Health. 2017;13:77. doi:10.1186/s12992-017-0301-1

24. Dirks JL. Alternative approaches to mentoring. Crit Care Nurse. 2021;41(1):e9–e16.

25. Sibiya MN, Ngxongo TSP, Beepat SY. The influence of peer mentoring on critical care nursing students’ learning outcomes. Int J Workplace Health Manag. 2018;11(3):130–142. doi:10.1108/IJWHM-01-2018-0003

26. Davey Z, Jackson D, Henshall C. The value of nurse mentoring relationships: lessons learnt from a work-based resilience enhancement programme for nurses working in the forensic setting. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2020;29:992–1001. doi:10.1111/inm.12739

27. Nimmons D, Giny S, Rosenthal J. Medical student mentoring programs: current insights. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2019;10:113–123.

28. Webb J, Brightwell A, Sarkar P, Rabbie R, Chakravorty I. Peer mentoring for core medical trainees: uptake and impact. Postgrad Med J. 2015;91:188–192.

29. Wilson G, Larkin V, Redfern N, Stewart J, Steven A. Exploring the relationship between mentoring and doctor’s health and wellbeing: a narrative review. J Royal Soc Med. 2017;110(5):188–197.

30. Levine S, O’Mahony S, Baron A, et al. Training the workforce: description of a longitudinal interdisciplinary education and mentoring program in palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2017;53(4):728–737. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.11.009

31. Hookman AA, Lalani N, Sultan N, et al. Development of an on-job mentorship programme to improve nursing experience of compassionate care. BMC Nurs. 2021;20:175. doi:10.1186/s12912-021-00682-4

32. Chanchlani S, Chang D, Ong JSL, Anwar A. The value of peer mentoring for the psychosocial wellbeing of junior doctors: a randomised controlled study. Med J Aust. 2018;209(9):401–405.

33. Sigurdsson EL. The wellbeing of health care workers. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2021;39(4):389–390. doi:10.1080/02813432.2021.2012352

34. Perlo J, Balik B, Swensen S, Kabcenell A, Landsman J, Feeley D. IHI Framework for Improving Joy in Work. IHI White Paper. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2017. Available from: https://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/IHIWhitePapers/Framework-Improving-Joy-in-Work.aspx.

35. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. A Guide to Promoting Health Care Workforce Well-Being During and After the COVID-19 Pandemic. Boston, Massachusetts: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2020. Available from https://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Publications/guide-to-promoting-health-care-workforce-well-being-during-and-after-The-COVID-19-pandemic.aspx.

36. Barton TD. Clinical mentoring of nurse practitioners: the doctors’ experience. Br J Nurs. 2013;15:15. doi:10.12968/bjon.2006.15.15.21689

37. Ong J, Swift C, Magill N, et al. The association between mentoring and training outcomes in junior doctors in medicine: an observational study. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e020721. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020721

38. Moreno-Milan B, Breitbart B, Herreros B, Olaciregui Dague K, Cristina Coca Pereira M. Psychological well-being of palliative care professionals: who cares? Palliat Support Care. 2021;19(2):257–261. doi:10.1017/S1478951521000134

39. Slater PJ, Edwards RM, Badat AA. Evaluation of a staff well-being program in a pediatric oncology, hematology and palliative care services group. J Healthc Leadersh. 2018;10:67–85. doi:10.2147/JHL.S176848

40. Søvold LE, Naslund JA, Kousoulis AA, et al. Prioritizing the Mental Health and Well-Being of Healthcare Workers: an Urgent Global Public Health Priority. Front Public Health. 2021;9:679397. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.679397

41. Yeung M, Nuth J, Stiell IG. Mentoring in emergency medicine: the art and the evidence. CJEM. 2010;12(2):143–149.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.