Back to Journals » Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment » Volume 11

Mental health status, aggression, and poor driving distinguish traffic offenders from non-offenders but health status predicts driving behavior in both groups

Authors Abdoli N, Farnia V, Delavar A, Dortaj F, Esmaeili A, Farrokhi N, Karami M, Shakeri J, Holsboer-Trachsler E, Brand S

Received 5 June 2015

Accepted for publication 6 July 2015

Published 10 August 2015 Volume 2015:11 Pages 2063—2070

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S89916

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Roger Pinder

Nasrin Abdoli,1,2 Vahid Farnia,3 Ali Delavar,4 Fariborz Dortaj,4 Alireza Esmaeili,5 Noorali Farrokhi,4 Majid Karami,6 Jalal Shakeri,3 Edith Holsboer-Trachsler,7 Serge Brand7,8

1International University of Imam Reza, Mashhad, Iran; 2Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran; 3Substance Abuse Prevention Research Center, Psychiatry Department, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran; 4Allameh Tabataba’i University, Tehran, Iran; 5Police University, Tehran, Iran; 6Baharestan Research Center, Kermanshah Transportation Terminal, Kermanshah, Iran; 7Center for Affective, Stress and Sleep Disorders, Psychiatric Clinics of the University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland; 8Department of Sport and Health Science, Sport Science Section, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland

Background: In Iran, traffic accidents and deaths from traffic accidents are among the highest in the world, and generally, driver behavior rather than technical failures or environmental conditions are responsible for traffic accidents. In a previous study, we showed that among young Iranian male traffic offenders, poor mental health status, along with aggression, predicted poor driving behavior. The aims of the present study were twofold, to determine whether this pattern could be replicated among non-traffic offenders, and to compare the mental health status, aggression, and driving behavior of male traffic offenders and non-offenders.

Methods: A total of 850 male drivers (mean age =34.25 years, standard deviation =10.44) from Kermanshah (Iran) took part in the study. Of these, 443 were offenders (52.1%) and 407 (47.9%) were non-offenders with lowest driving penalty scores applying for attaining an international driving license. Participants completed a questionnaire booklet covering socio-demographic variables, traits of aggression, health status, and driving behavior.

Results: Compared to non-offenders, offenders reported higher aggression, poorer mental health status, and worse driving behavior. Among non-offenders, multiple regression indicated that poor health status, but not aggression, independently predicted poor driving behavior.

Conclusion: Compared to non-offenders, offenders reported higher aggression, poorer health status and driving behavior. Further, the predictive power of poorer mental health status, but not aggression, for driving behavior was replicated for male non-offenders.

Keywords: driving behavior, aggression, health status, male traffic offenders, non-offenders, replication

Introduction

Compared to Western countries (Switzerland: 3.4/100,000 people per annum; Germany: 4.3/100,000 people per annum; Unites States: 11.6/100,000 people per annum), traffic deaths in Iran are tremendously higher (24,1/100,000 people per annum).1,2 Traffic accidents are the main cause of injuries requiring surgical intervention,3 and the second largest cause of mortality in Iran.4–6

Further, given that worldwide it has been estimated that 90%–95% of road crashes can be attributed to driver behavior and not to technical malfunctions,7 it would seem to be of particular importance to focus on the determinants of driver behavior.

One focus of research has been on associations between personality traits and driving behavior.8–11 The main pattern to emerge from this is an association between poor driving behavior and trait anxiety,11 excitement seeking,8 narcissism,10 and antagonism, negative affectivity, and disinhibition.9 This approach thus points to a particular constellation of personality traits as the source of poor driving behavior. More specifically, Hilton et al12 reported associations between severe and very severe self-reported symptoms of depression and increased road accidents among professional heavy goods vehicle drivers. To explain this association, Hilton et al12 supposed that not symptoms of depression per sé, but the lack of concentration and poor sleep might have an unfavorable impact on driving behavior. Further, Scott-Parker et al13 showed that among novice drivers, symptoms of depression predicted risky behavior, while in a further analysis, Scott-Parker et al14 reported that not symptoms of depression, but anxiety predicted risky driving among female but not male novice drivers. Thus, risky driving behavior seemed to be associated with symptoms of depression12,13 and anxiety14 among professional drivers12 and novice drivers.13,14

Another line of research has examined the association between poor driving behavior and aggression. Thus, aggressive driving is acknowledged as a contributor to motor vehicle accidents, and the Manchester Driving Behavior Questionnaire (DBQ15) explicitly includes aggressive reactions (ie, aggressive violations and ordinary violations) as factors adversely affecting driving. In this regard, an overlap with the personality traits of antagonism, negative affectivity, and disinhibition has also been observed.9 Similarly, Stephens and Sullman16 identified trait aggression as a predictor of crash-related behaviors among drivers from the United Kingdom and the Irish Republic. Not surprisingly, aggressive forms of expression were higher for drivers who reported initiating road rage incidents, and total scores for aggressive expression were also higher for drivers who reported recent crash-related events, such as loss of concentration, losing control of their vehicle, moving violations, near-misses, and major crashes.16

Turning to the relation between driving behavior and mental health status, there is rather less research. Possis et al17 showed that among veterans, poor and risky driving behavior and poor mental health status were associated. Other researchers18 have focused on the association between general mental health status and driving ability among the elderly. Also, in a previous study,19 we showed that poor mental health status was associated both with poor driving behavior and aggression, while aggression was also associated with poor driving behavior. However, when both were entered in a regression equation, only poor health status emerged as a predictor of poor driving behavior.

Given that the previous study19 was among the first to report this pattern of results, the first aim of the present study was to replicate these findings. To do so, these associations were investigated among a sample of traffic non-offenders. Further, differences between traffic offenders and non-offenders with respect to driving behavior and health status have not so far been examined. The second aim of the present study was therefore to compare the mental health status, aggression, and driving behavior of male traffic offenders with those of non-offenders.

To summarize, traffic accidents make a substantial contribution to the high mortality rates and health care costs in Iran. Psychological processes that might explain the high rate of traffic accidents include those related to poor health status, aggression, and socio-demographic characteristics. However, to our knowledge, no study has yet compared the mental health status, aggression, and driving behavior of Iranian male traffic offenders and non-offenders. The aims of the present study were therefore twofold: 1) to replicate previous findings19 and 2) to compare the above-mentioned variables, and also the socio-demographic characteristics, of traffic offenders with those of non-offenders. In our view, the present study has the potential to contribute to a better understanding of the psychological mechanisms and socio-demographic factors underlying traffic accidents, and to help focus efforts to reduce traffic accidents in Iran.

We hypothesized first that, compared to non-traffic offenders, traffic offenders would report poorer mental health status, more aggression, and poorer driving behavior. Second, we expected to replicate our previous findings19 with non-offenders: poor mental health status, aggression, and poor driving behavior would also be associated among non-offenders, and poor mental health status but not aggression would predict poor driving behavior.

Methods

Sample

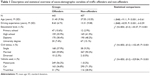

A total of 850 male participants (mean age =34.34 years, standard deviation =10.31; range: 15–70 years; median: 32.00 years) took part in the present study. Of these, 443 (50.95%) were traffic offenders, and 407 (49.05%) were traffic non-offenders. Sample characteristics are reported in Table 1. Participants were recruited from February to October 2014 in the Police Center of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran. Traffic offenders had to undergo a brief medical and psychological check because they had recently violated traffic regulations on at least three separate occasions, and because they had the highest number of points on their driving licenses according to police reports. Participants were fully informed about the aims and scope of the present study, and they were assured that all data were anonymized in the analyses and study reporting. Inclusion criteria for traffic offenders were: 1) male sex; 2) non-accidental traffic violations on at least three separate occasions and taken to the police station for prosecution; 3) willing and able to complete written questionnaires; and 4) giving written informed consent. Inclusion criteria for the non-offenders group were: 1) male sex; 2) lowest number of negative points on driving license; that is to say: no accidents or traffic penalties within the last 10 years; 3) candidate for the international driving license; 4) willing and able to complete written questionnaires; and 5) giving written informed consent. Exclusion criteria for both groups were: 1) not willing or not able to complete written questionnaires; 2) severe health issues such as psychiatric disorders or somatic disorders; and 3) a history of substance abuse. The Review Board of the University of Imam Reza of Mashhad (Mashhad, Iran) approved the study, which was conducted following the rules laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki.

| Table 1 Descriptive and statistical overview of socio-demographic variables of traffic offenders and non-offenders |

Tools

Socio-demographic and driver-related information

This questionnaire asked for sex, age (years), highest educational level (primary school, high school, diploma, university degree), civil status (single, married, divorced/widowed), years of driving experience (years), and vehicle driven when traffic violations occurred (motorcycle, car, truck/bus).

Driving behavior

Participants completed the Manchester DBQ15 (Farsi version: Oreyzi Samani and Haghayegh20). The DBQ is a self-rating questionnaire consisting of 50 items measuring aberrant driving behaviors, and focuses on aggressive violations (eg, “Sound your horn to indicate your annoyance with another road user”; “Become angered by another driver and give chase with the intention of giving him/her a piece of your mind”), ordinary violations (eg, “Disregard the speed limit on a residential road/motor way”; “Overtake a slow driver on the inside”; “I drive so close to the car in front that it would be difficult to stop in an emergency”), errors (eg, “Underestimate the speed of an oncoming vehicle when overtaking”; “Fail to check your rear-view mirror before pulling out, changing lanes, etc”), and lapses (eg, “Attempt to drive away from the traffic lights in third gear”; “Forget where you left your car in a car park”; “Intending to drive to destination A, you “wake up” to find yourself on the road to destination B”). Responses are given on six-point Likert scales ranging from zero (= never) to five (= nearly all the time), with higher mean scores reflecting more numerous violations, errors, and lapses (Cronbach’s alpha =0.89).

General health

Participants completed the General Health Questionnaire21 (Farsi version: Malakouti et al22). The General Health Questionnaire is a self-rating questionnaire to identify psychological distress. It consists of 28 items and assesses anxiety, insomnia, depression, social dysfunction, and somatic health. Typical items are: “I’m afraid to lose control”; “I have no hope”; “I feel useless”; “I’m sweating a lot”. Answers are given on four-point Likert scales ranging from zero (= not at all) to three (= more than usual), with higher sum scores reflecting more severe health issues (Cronbach’s alpha =0.89).

Aggression

Participants completed the Aggression Questionnaire23 (Farsi version: Zahedi24). The Aggression Questionnaire is a self-rating questionnaire consisting of 29 items focusing on physical aggression, verbal aggression, anger, and hostility. Typical items are: “I have become so mad that I have broken things”; “I have threatened people I know”, or “I have trouble controlling my temper”. Answers are given on seven-point Likert scales ranging from one (= extremely uncharacteristic of me) to seven (= extremely characteristic of me), with higher scores reflecting a higher tendency toward aggressive behavior (Cronbach’s alpha =0.85).

Statistical analysis

First, two t-tests and three chi-square tests were performed to explore differences between offenders and non-offenders in socio-demographic characteristics. Next, a series of multivariate ANCOVAs was performed with group (offenders vs non-offenders) as the independent factor, age, driving experience, educational level, civil status, and vehicle driven as covariates, and mental health status, aggression, and driving behavior as dependent variables. Additionally, to replicate previous findings,19 correlations were computed between the main variables of driving behavior, aggression, health status, age, and driving experiences. Further, as in the previous study, multiple regression analyses were performed with driving behavior (aggressive violations, ordinary violations, errors, and lapses) as dependent variable and aggressive traits (physical aggression, verbal aggression, anger, hostility, and total score) and health status (anxiety and insomnia, depression, social dysfunction, physical health, and total health score) as predictors. Effect sizes were reported for t-tests (Cohen’s d) and for ANCOVAs (partial eta squared [η2]), with 0.059≥ η2 ≥0.01 indicating small (S), 0.13≥ η2 ≥0.06 indicating medium (M), and η2 ≥0.14 indicating large (L) effect sizes.

The nominal level of statistical significance was set at alpha =0.05. Statistical computations were performed with SPSS® 20.00 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) for Apple®.

Results

Socio-demographic variables and driving experiences

Table 1 reports the descriptive and statistical indices of socio-demographic and driving experiences-related information for offenders and non-offenders.

Compared to non-offenders, offenders were younger, single, reported less driving experience and poorer educational level, and drove a motorcycle as their most used vehicle. Accordingly, age, driving experience, civil status, educational level, and motorcycle use were introduced as covariates in the following analyses.

Mental health status, aggression, and driving behavior of offenders and non-offenders

Table 2 reports the descriptive and statistical indices of mental health status, aggression, and driving behavior, comparing between offenders and non-offenders.

Compared to non-offenders, and after controlling for age, driving experience, educational level, civil status, and vehicle used, offenders reported poorer mental health status (higher symptoms of anxiety, depression and insomnia, social dysfunction, physical health, and higher total score), higher aggression (physical aggression, verbal aggression, anger, hostility, and total sum score), and poorer driving behavior (lapses, errors, aggressive violations, and ordinary violations).

Associations between mental health, aggression, and driving behavior among non-offenders

To replicate our previous observations,19 correlations were calculated between mental health, aggression, and driving behavior among non-offenders (Table 3). Aggression was associated with poor driving behavior, as was poor health status. Aggression and health status were also associated with each other.

| Table 3 Descriptive and correlative overview of aggression, health, driving behavior, and age and driving experience |

Predicting driving behavior

To predict driving behavior, multiple regression analyses were executed with driving behavior as the dependent variable, and with aggression traits and health status as predictors.

Poor health status (anxiety and insomnia, depression, social dysfunction, total score; betas from 0.55 to 0.69, P<0.001 r from 0.47 to 0.55; R2 from 0.22 to 0.30; F [1, 848] = from 32.40 to 53.20, P<0.001), but not aggression (betas from 0.01 to 0.10, P>0.15 r from 0.02 to 0.09; R2 from 0.0004 to 0.0081; F [1, 848] <0.05, P>0.40), independently predicted poor driving behavior (aggressive violations, ordinary violations, errors, and lapses).

Discussion

The key findings of the present study were that compared to non-offenders, Iranian males traffic offenders were young singles with less driving experience, lower educational level, motorcycle users, reporting poorer mental health status, more aggression, and poorer driving behavior. Further, we replicated previous findings in showing that poor mental health status, but not aggression, predicted poor driving behavior. The current findings add to the literature, showing that socio-demographic, psychological, and driving behavior-related dimensions best characterized male traffic offenders and that mental health status again proved to be the main predictor of driving behavior.

Two hypotheses were formulated and each of these is considered in turn.

We hypothesized first that, compared to non-traffic offenders, traffic offenders would have poorer mental health status, more aggression, and poorer driving behavior, and this was fully confirmed. Therefore, we were able to replicate previous studies that have reported similar findings. Possis et al,17 Morris et al,18 Hilton et al,12 Scott-Parker et al,13,14 and Abdoli et al19 showed that poor mental health status in terms of symptoms of anxiety, depression and insomnia, and social dysfunction were associated with poor driving behavior. We believe the present pattern of results adds to the current literature in an important way, given that to the best of our knowledge these associations have been observed only once19 among Iranian male traffic offenders.

The data available from this study do not provide any direct insight into the underlying cognitive-emotional processes involved, though in our view concepts derived from cognitive psychology might help to explain these associations. First, the working memory model advanced by Baddeley and Hitch25 claims that working memory as part of the human memory system is responsible for keeping current information available while also retrieving information from long-term memory. Working memory also directs and controls concentration, understood as current capacity to focus cognitive-emotional resources on a specific task. Working memory also elaborates and brings into consciousness cognitive-emotional processes, so-called current concerns, highly involved in current information elaboration. Current concerns refer to personal needs, thoughts, worries, and often unresolved issues. Following the theoretical framework of Baddeley and Hitch,25 working memory is limited in the speed, accuracy, and amount of information that may be elaborated within a specific time frame. Accordingly, working memory is unable to store, direct, modulate, elaborate, or focus all information at the same time. Therefore, it seems plausible that people with higher levels of anxiety and depression, more social issues, and poorer sleep are less accurate in everyday motor skills and behavior such as driving. In brief, and though we cannot confirm this with the present data, we believe that elevated health difficulties lead to poorer driving behavior due to the limited capacity of working memory. We also note that performance in neuropsychological assessments is lower in people suffering from psychiatric disorders, and one psychological explanation for this focuses on the impaired capacity of working memory.25,26 Other frameworks to describe and explain selective attention derived from cognitive psychology may also be helpful here:26 1) for example, both trait-based anxiety and situation-related anxiety have been found to affect attention;27–29 2) overall arousal affects attention (and therefore also driving behavior) in that, for instance, drowsiness, tiredness, fatigue, and being under sedative medication may dramatically limit attention; 3) task difficulty has an impact on selective attention; thus, even if rather speculative, driving a motorcycle might be more difficult and complex than driving a car, in that the former both allows and demands a greater degree of freedom and choice in traffic behavior, while dramatically also increasing the risk of traffic accidents; and 4) amount of practice also impacts on selective attention (and driving behavior), and data confirm that, compared to non-offenders, traffic offenders had less driving experience.

We hypothesized second, that among non-offenders, poorer mental health status, more aggression, and poorer driving behavior would also be associated, and this was fully confirmed. Further, as expected, we were also able to confirm that poor mental status, but not aggression, predicted poor driving behavior. Therefore, we were able to replicate previous findings19 and can claim that this particular pattern of results appears to be robust. At present, there is no adequate theoretical framework available to account for this pattern of results. We note, however, that cognitive performance is dramatically decreased, for instance in patients suffering from panic disorder,30 major depressive disorder,31 and post-traumatic stress disorder.32 Further, in the absence of such a framework, we advance the following possibility. Drawing on Lazarus and Folkman’s33 concept of coping with stress, aggression, and aggressive expression could be regarded as emotion-focused coping strategies (in contrast to problem-focused strategies). Further, symptoms of anxiety, depression, and social dysfunction might also be considered as emotion-focused coping strategies in that a person seems to be unable to solve problems or to eliminate stressors but tries only to cope with the emotions related to stress. Variance in aggression and aggressive expression may overlap considerably with variance in symptoms of anxiety and depression, and aggressive traits may be treated as a specific aspect of health status. Future studies might focus on the extent to which aggressive traits and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and insomnia do indeed share common variance.

In conclusion, if we assume that behavior is both the result of and the starting point for cognitive-emotional processes; the present findings suggest that poor driving behavior might be both the result of and the starting point for complex cognitive-emotional processes comprising poor mental health status and aggression.

Despite the intriguing findings, several limitations warn against overgeneralizations of the present results. First, the study is cross-sectional and precludes by definition any conclusions as regards causal direction in the associations between health status, aggression, and driving behavior. In this regard, it seems likely that there are reciprocal processes between driving behavior and cognitive-emotional processes. Second, we relied entirely on self-reports. Given that self-reports can be biased, future studies should also include experts’ ratings. This holds particularly true for psychological health, as it might be expected that psychiatric disorders such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and substance abuse might affect driving behavior. Third, the present pattern of results might be due to further latent, but unassessed dimensions that could have biased two or more variables in the same direction. In this regard, future studies might introduce impulsive behavior/impulse control skills as possible factors. Fourth, given that only males were assessed, we cannot say whether the present pattern of results would also hold for female drivers. Fifth, no objective physiological data were collected; such data might have allowed us to illuminate the underlying neurophysiological processes linking aberrant driving behavior, poor health status, and aggression. Sixth, the data do not provide any insight into possible work-related, stress-related, or motivational issues underlying current driving behavior, health status, or aggression. Though highly speculative, one might anticipate that work load, job insecurity, family strain, financial issues, and other stressors have an impact on the cognitive-emotional processes involved in stress, anxiety, and depression. If we take into account that being single and having low educational attainment were associated with poor health status, it is possible that the socio-economic consequences34 of lower educational attainment might underlie or at least contribute to higher cognitive-emotional stress, lower health status, and poorer driving behavior. Last, we did not distinguish between participants from urban and rural areas, though it is conceivable that specific rural and urban traffic characteristics may have an influence in driving behavior.

Conclusion

Among a large sample of male Iranian participants, traffic offenders, relative to non-traffic offenders, were younger, more likely to be single, with lower education, more often driving motorcycles, and reporting poorer mental health status, increased aggression, and poorer driving behavior. Further, poor mental health status, but not aggression, predicted poor driving behavior, a pattern of results also observed among non-offenders, suggesting therefore a robust pattern of associations.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nick Emler (University of Surrey, Surrey, UK) for proofreading the manuscript. The present work is the doctoral thesis of Nasrin Abdoli.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

World Health Organization (WHO). Global Status Report on Road Safety 2013: Supporting A Decade of Action. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO); 2013. | ||

Moradi S, Khademi A. Survey of victims of car accidents year 1387. J Forensic Med (Persian). 2009;15:21–28. | ||

Zargar M, Kaji A, Karbkhsh M, Zarei MR. Epidemiology study of facial injuries during a 13 month of trauma registry in Tehran. Indian J Med Sci. 2004;58:109–114. | ||

Montazeri A. Road-traffic-related mortality in Iran. A descriptive study. Public Health. 2004;118:110–113. | ||

Zangooei Dovom H, Shafahi Y, Zangooei Dovom M. Fatal accident distribution by age, gender and head injury, and death probability at accident scene in Mashhad, Iran, 2006–2009. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2013;20(2):121–133. | ||

Naghavi M, Shahraz S, Bhalla K, et al. Adverse health outcomes of road traffic injuries in Iran after rapid motorization. Arch Iran Med. 2009;12:284–294. | ||

Rumar K. The role of perceptual and cognitive filters in observed behavior. In: Evans L, Schwing RC, editors. Human Behaviour and Traffic Safety. New York NY: Plenum Press; 1985:151–165. | ||

Mallia L, Lazuras L, Violani C, Lucidi F. Crash risk and aberrant driving behaviors among bus drivers: the role of personality and attitudes towards traffic safety. Accid Anal Prev. 2015;79:145–151. | ||

Beanland V, Sellbom M, Johnson AK. Personality domains and traits that predict self-reported aberrant driving behaviours in a southeastern US university sample. Accid Anal Prev. 2014;72:184–192. | ||

Edwards BD, Warren CR, Tubré TC, Zyphur MJ, Hoffner-Prillaman R. The validity of narcissism and driving anger in predicting aggressive driving in a sample of young drivers. Hum Perform. 2013;26:191–210. | ||

Pourabdian S, Azmoon H. The relationship between trait anxiety and driving behavior with regard to self-reported Iranian accident involving drivers. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4:1115–1121. | ||

Hilton MF, Staddon Z, Sheridan J, Whiteford HA. The impact of mental health symptoms on heavy goods vehicle drivers’ performance. Accid Anal Prev. 2009;41:453–461. | ||

Scott-Parker B, Watson B, King MJ, Hyde MK. The influence of sensitivity to reward and punishment, propensity for sensation seeking, depression, and anxiety on the risky behaviour of novice drivers: a path model. Br J Psychol. 2012;103:248–267. | ||

Scott-Parker B, Watson B, King MJ, Hyde MK. A further exploration of sensation seeking propensity, reward sensitivity, depression, anxiety, and the risky behaviour of young novice drivers in a structural equation model. Accid Anal Prev. 2013;50:465–471. | ||

Reason J, Manstead A, Stradling S, Baxter J, Campbell K. Errors and violations on the road: a real distinction? Ergonomics. 1990;33:1315–1332. | ||

Stephens AN, Sullman MJ. Trait predictors of aggression and crash-related behaviors across drivers from the United Kingdom and the Irish Republic. Risk Anal. 2015. | ||

Possis E, Bui T, Gavian M, et al. Driving difficulties among military veterans: clinical needs and current intervention status. Mil Med. 2014;179:633–639. | ||

Morris JN, Howard EP, Fries BE, Berkowitz R, Goldman B, David D. Using the community health assessment to screen for continued driving. Accid Anal Prev. 2014;63:104–110. | ||

Abdoli N, Farnia V, Delavar A, et al. Poor mental health status and aggression are associated with poor driving behavior among male traffic offenders. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015. | ||

Oreyzi Samani SHR, Haghayegh SA. Psychometric properties of the Manchester driving behavior questionnaire. Payesh. 2010;9:21–28. | ||

Goldberg DP. Manual of the General Health Questionnaire. Windsor: NFER Publishing; 1978. | ||

Malakouti SK, Fatollahi P, Mirabzadeh A, Zandi T. Reliability, validity and factor structure of the GHQ-28 used among elderly Iranians. Int Psychogeriatr. 2007;19(4):623–634. | ||

Buss AH, Perry M. The aggression questionnaire. J Pers Social Psychol. 1992;63:452–459. | ||

Zahedi S. Construction and validation of a scale for measuring aggression. J Edu Psychol. 2001;3:73–102. | ||

Baddeley AD, Hitch G. Working memory. In: Bower GH, editor. The Psychology of Learning and Motivation: Advances in Research and Theory. New York: Academic Press. 1974:47–89. | ||

Sternberg RJ, Sternberg K. Cognitive Psychology. 6th ed. Belmont CA: Wadsworth; 2009. | ||

Eysenck MW, Byrne A. Anxiety and susceptibility to distraction. Pers Ind Diff. 1992;13:793–798. | ||

Eysenck MW, Calvo MG. Anxiety and performance: the processing efficiency theory. Cog Emot. 1992;6:409–434. | ||

Eysenck MW, Graydon J. Susceptibility to distraction as a function of personality. Pers Ind Diff. 1989;10:681–687. | ||

Alves MR, Pereira VM, Machado S, Nardi AE, Oliveira e Silva AC. Cognitive functions in patients with panic disorder: a literature review. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2013;35:193–200. | ||

Evans VC, Iverson GL, Yatham LN, Lam RW. The relationship between neurocognitive and psychosocial functioning in major depressive disorder: a systematic review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75:1359–1370. | ||

Qureshi SU, Long ME, Bradshaw MR, et al. Does PTSD impair cognition beyond the effect of trauma? J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;23:16–28. | ||

Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal and Coping. New York: Springer; 1984. | ||

Tapp A, Pressley A, Baugh M, White P. Wheels, skills and thrills: a social marketing trial to reduce aggressive driving from young men in deprived areas. Accid Anal Prev. 2013;58:148–157. |

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.