Back to Journals » International Journal of Women's Health » Volume 15

Maternal Strangulated Diaphragmatic Hernia with Gangrene of the Entire Stomach During Pregnancy: A Case Report and Review of the Recent Literature

Authors Chae AY, Park SY, Bae JH , Jeong SY, Kim JS, Lee JS, Kim SJ, Lee SJ , Lee SH

Received 26 July 2023

Accepted for publication 8 November 2023

Published 15 November 2023 Volume 2023:15 Pages 1757—1769

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S432463

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Elie Al-Chaer

Ah Yeong Chae,1 So Yeon Park,1 Jung Hyun Bae,1 So Yeon Jeong,1 Ji Su Kim,1 Jeong Soo Lee,2 Soo Jin Kim,2 Soo Jeong Lee,3 Sang Hun Lee3

1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea; 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Eulji University, Nowon Eulji Medical Center, Seoul, Korea; 3Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Ulsan University Hospital, Ulsan, Korea

Correspondence: Sang Hun Lee, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Ulsan University Hospital, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, 290-3 Joenha-Dong, Dong-Gu, Ulsan, 682-714, Korea, Tel +82-052-250-8786, Fax +82-052-250-7163, Email [email protected]

Background: Bochdalek hernia (BH) of congenital diaphragm hernia is infrequently seen in adults. Strangulation of the diaphragm hernia has been recognized as a severe complication. Among several factors, pregnancy is an important cause of diaphragm hernia’s deterioration. However, nausea, vomiting, and upper abdominal pain are often considered non-specific pregnancy-related symptoms.

Case Presentation: We report a case of a 39-year-old (gravida II, para I) multigravida woman with a delayed diagnosis of strangulated herniated viscera complicating total gastric gangrene at 26+1 weeks’ gestation. The preoperative diagnosis was confirmed by an X-ray examination and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). After identifying the size and severity of the herniated contents through video-assisted thoracoscopy (VAT), we immediately converted to abdominal laparotomy. Antenatal corticosteroids were administered simultaneously with diagnosis to promote fetal maturity. The fetal condition was maintained well in the maternal uterus during the operation. Careful monitoring of the fetus and the mother’s clinical conditions should be performed during expectant management to achieve delayed delivery after maternal surgical correction. Delivery was completed through cesarean delivery at 27+1 weeks of gestation.

Conclusion: Despite the rarity of maternal Bochdalek hernias during pregnancy, early diagnosis and appropriate treatment via multidisciplinary care are essential for maternal and fetal outcomes.

Keywords: strangulation, Bochdalek hernia, pregnancy

A Letter to the Editor has been published for this article.

A Response to Letter by Professor Augustin has been published for this article.

Introduction

Diaphragmatic hernia, which was first described in 1610 through Ambroise Paré’s necropsy findings, is categorized into three types: congenital, acquired, and traumatic. Congenital types include posterolateral (Bochdalek) or substernal (Morgagni) portions, while acquired types include the esophageal hiatus (hiatal) or the aortic or caval openings. Bochdalek hernia (BH) of congenital diaphragm hernia (CDH) is considered a life-threatening disease in neonatal infants with a prevalence of 0.8 to 5/1000.1 However, Mullins et al reported in a previous paper that the incidence of asymptomatic adult Bochdalek hernia was 0.17% based on 13,138.2 Despite the rarity of maternal Bochdalek hernias during pregnancy, pregnancy is associated with one factor that suddenly exacerbates symptoms of asymptomatic adult Bochdalek hernia.3 Therefore, if diagnosis and treatment are delayed, the results may be poor outcomes due to obstruction, perforation, ischemia, gangrene, or necrosis of internal organs.4 This is the rare case of delayed delivery of a pregnant patient who survived after antenatal surgery for a congenital diaphragmatic hernia with gangrene of the entire stomach.

Case Report

A 39-year-old woman (gravida 2, para 1) at 26+1 weeks’ gestation visited our emergency room with severe epigastric pain accompanied by projectile vomiting. The patient had been suffering from epigastric pain for the last two months. A few days ago, before she came to the emergency room, she could not even drink water due to vomiting and nausea. On arrival at the emergency department, she had blood pressure of 95/72 mmHg, pulse rate of 160/ min, body temperature of 37 0.2° C, and respiratory rate of 20/ min. An abdominal examination showed left-side tenderness and a gravid uterus. Laboratory parameters had a white cell count of 21,960/µL, hemoglobin of 11.1 g/dL, platelet count of 253,000/µL, D-dimer of 4.61 µg/mL, and C-reactive protein of 14.70 mg/dL. Chest X-ray revealed the left hemidiaphragmatic eventration accompanied by multiple passive collapses in the left lung. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen was requested for a definitive diagnosis. A Levin tube was inserted as the patient waited for the MRI examination. Through the MRI reporting, the stomach and distal transverse colon had herniated in the left intrathorax (Figure 1). The gastroesophageal junction and the duodenal bulb were squeezing and stretching, and the spleen’s anterior displacement was shown (Figure 1). As a result of evaluating the fetal condition in the uterus through an emergency obstetric ultrasound such as echocardiography and Doppler, the fetal condition was good. The estimated fetal weight was 988g, the presentation was breech, the fetal heartbeat rate was 150/min, and the fetal movement was normal. The patient underwent surgery under emergency conditions in the cardiothoracic and general surgery departments. Laparoscopic surgery was attempted first, but the surgical team switched to open surgery because of a large amount of bloody fluid and severe stomach and spleen infarction. The left posterior diaphragm had a defect of more than 10cm (Figure 2). The entire stomach and the splenic flexure of the transverse colon were found inside the left hemithorax. When the contents of the diaphragmatic hernia were moved manually into the abdomen, the stomach showed a totally ischaemic change with gangrene (Figure 2). Therefore, the total gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y esophagojejunostomy were performed. Additionally, severe splenomegaly and necrotic changes in the spleen were found. A splenectomy was performed. Later on, primary closure of the diaphragmatic defect and chest tube insertion at the anterior axillary line of the 9th intercostal space was performed. Meanwhile, fetal monitoring by portable Doppler was performed during surgery. After surgery, she was treated in the intensive care unit for three days and then transferred to a general ward. The patient received a tocolytic agent by continuous intravenous infusion of ritodrine to inhibit preterm labor. However, on the 7th day after surgery, the patient had to have a cesarean delivery due to labor pain. The baby was born at 1110g at 27+1 gestational weeks. (The Apgar score was 6 at 1 min and 7 at 5 min after birth.) Two months later, the patient was discharged with a pigtail inserted in the left subphrenic space. Abdominal computerized tomography (CT) was performed and revealed a 6-cm width of complicated fluid collection on the day after the cesarean delivery (Figure 3). One month after discharge from the hospital, the pigtail was removed. One year later, an outpatient abdominal CT showed no diaphragmatic hernia recurrence (Figure 3).

|

Figure 2 (A) Perioperative photograph showing a large defect in the left posterior dome of the diaphragm. (B) Postoperative photograph showing necrosis of the entire stomach. |

Discussion

We reported a case of a multigravida woman who had strangulated herniated viscera, complicating total gastric gangrene in 2nd trimester. Brown et al announced that pregnancy causes symptomatic Bochdalek hernia in an adult.3 Choi et al5 systemically reviewed case reports and case series reporting maternal Bochdalek hernia in pregnant women, in which mean age at diagnosis accompanying symptoms are 28.5 years, the parity was primigravida (43%), multiparous (36%), and unknown (21%), and the gestational age was antenatal period (65%) and postpartum including intrapartum (35%). These hernia defects can easily occur during delivery but can occur without delivery in the second or third trimester of pregnancy.

Pregnancy suddenly exacerbates symptoms of asymptomatic adult Bochdalek hernia regardless of gestational age.3 Pregnant women with symptoms should undergo emergency surgery regardless of their gestational age. However, it is debatable whether to choose conservative or surgical treatment for accidentally recognized asymptomatic Bochdalek hernia of pregnant women. On maternal Bochdalek hernia during pregnancy, Choi et al5 found that obstruction, perforation, ischemia, gangrene, or necrosis of the herniated organ accounted for 44%. Obstruction, perforation, ischemia, gangrene, or necrosis of the herniated organ increases maternal (11% of collected cases)6,7 and fetal-neonatal mortality (21% of collected cases).6–9

Therefore, many authors argue that immediate treatment under elective surgery is needed regardless of gestational age.10 For pregnant women before gestational 36 weeks, maternal expectant management of pregnancy maintenance is important until delivery after emergent surgery, which delays delivery until full administration of antenatal corticosteroids, and in a previous study, maternal expectant management periods ranged from 3 days to 13 weeks. In this case, after the surgical approach of the total gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y esophagojejunostomy. We achieved an additional one-week extension of the gestation period until delivery by uncontrolled preterm labor after steroid loading and fetal maturation during expectant management, including close monitoring of the fetal and maternal clinical conditions.

Proper nutrition support is important because it can be related to the morbidity of pregnant women and fetuses. Therefore, nutrition support can be supplied through a nasogastric tube, jejunostomy, or parenteral feeding through peripheral or central intravenous vessels. Recommendations for dietary allowance for pregnant women are 2200–2900 kcal/day with 7.6 g/day protein, 175 g/day carbohydrates, and additional vitamin-mineral supplement requirements.11 Our patient maintained NPO for five days until the bowel movements recovered. The alternative option for this NPO period was taken into account as total parenteral nutrition (TPN; smofkabiven 80 cc/hr; 2074 kcal/day) via a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) to achieve the objective target calories for pregnancy nutrition (2100 kcal/day) of the 2nd trimester through counseling of NST (nutrition support team). However, it should be considered that complications of parenteral nutrition occur frequently and may be severe if clinicians do not change to enteric feeding. As a result, she took earlier delivery at 27+1 weeks by cesarean delivery due to fetal breech presentation and uncontrolled preterm labor within 7 days after maternal emergent surgical repair by visceral incarceration.

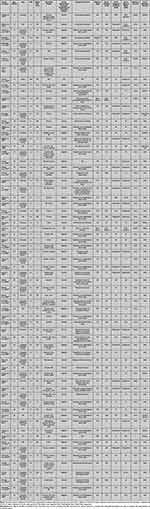

Finally, in Table 1, we summarized the clinical features, treatment approaches, and adverse outcomes for mothers and fetuses/neonates in all documented cases associated with maternal diaphragmatic hernia, including congenital (Bochdalek hernia), hiatal, and traumatic hernia during pregnancy. From a clinical perspective, through the reviewed 69 cases, this is the first case of delayed delivery of a pregnant patient who survived after antenatal surgery for a congenital diaphragmatic hernia with gangrene of the entire stomach. Etiological classification of diaphragmatic hernia was 32 (46%) congenital hernia,7,9,10,12–39 6 (9%) hiatal hernia,40–45 17 (25%) traumatic hernia,21,23,46–57 1 congenital hernia combined with hiatal hernia,7 13 (19%) unspecified type.11,58–69

|

Table 1 The Current Literature on a Diaphragmatic Hernia During Pregnancy |

From the reviewed 69 cases, diaphragmatic hernia demonstrated maternal death in 10% (7/69) of the cases (including 1 case that died within 1 hour on admission) and fetal deaths in 17% (12/69) of cases (FDIU, 2; stillborn, 8; death after birth, 2). Out of 29 cases with signs of bowel obstruction, ischemia, and perforation of herniated organs,7,9,16–18,22–24,26,28,30,35,37,41,44,46,48,49,53–57,60,64,66,67 there were 6 maternal deaths and 7 fetal deaths (FDIU, 1; stillborn, 4; death after birth, 2). Our data showed that there were 68% (17/25) in 1st and the 2nd trimester, 32% (8/25) in the third trimesters for delayed delivery after surgery with hernia diagnosis, 20% (2/10) in 1st and 2nd trimesters, and 80% (8/10) in 3rd trimesters for simultaneous delivery with surgery. It is important to recognize that premature birth has been reported in 26 of the 69 cases of diaphragmatic hernia,7,9–11,21,23,24,26–29,32,38,39,41,49–51,55,56,60,64,65,70 resulting in 2 maternal and 7 fetal deaths.

Conclusion

Any delay in diagnosing and treating abdominal herniated viscera’s strangulation will lead to a poor outcome by obstruction, perforation, ischemia, gangrene, or necrosis of visceral organ. Therefore, maternal diaphragmatic hernias during pregnancy should undergo surgical repair under elective surgery through multidisciplinary cooperation. Providing adequate nutritional support for mothers and fetuses during postoperative pregnancy management care is crucial to reducing morbidity and mortality.

Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

The patient reported in this manuscript has agreed in written informed consent to participate in this study and to publish details of her case and accompanying photographs. Institutional approval is not required to publish the case details in accordance with local legislation and institutional requirements.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank our patients and all the participating investigators involved in the conduct of this study.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation, or all these areas; took part in drafting, revising, or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

No funding sources were involved in this study.

Disclosure

All authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. McGivern MR, Best KE, Rankin J, et al. Epidemiology of congenital diaphragmatic hernia in Europe: a register-based study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2015;100(2):F137–44. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2014-306174

2. Mullins ME, Stein J, Saini SS, Mueller PR. Prevalence of incidental Bochdalek’s hernia in a large adult population. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177(2):363–366. doi:10.2214/ajr.177.2.1770363

3. Brown SR, Horton JD, Trivette E, Hofmann LJ, Johnson JM. Bochdalek hernia in the adult: demographics, presentation, and surgical management. Hernia. 2011;15(1):23–30. doi:10.1007/s10029-010-0699-3

4. Hedblom CA. THE SELECTIVE SURGICAL TREATMENT OF DIAPHRAGMATIC HERNIA. Ann Surg. 1931;94(4):776–785. doi:10.1097/00000658-193110000-00031

5. Choi JY, Yang SS, Lee JH, et al. Maternal bochdalek hernia during pregnancy: a systematic review of case reports. Diagnostics. 2021;11(7). doi:10.3390/diagnostics11071261

6. Hodge K. Diaphragmatic hernia complicated by gastric ulcer and pregnancy. Br J Radiol. 1950;23(273):573. doi:10.1259/0007-1285-23-273-573-b

7. Osborne W, Foster C. Diaphragmatic hernia complicating pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1953;66(3):682–684. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(53)90087-8

8. Flood JL. Foramen of Bochdalek hernia in pregnancy. J Indiana State Med Assoc. 1963;56:32–34.

9. Gimovsky ML, Schifrin BS. Incarcerated foramen of Bochdalek hernia during pregnancy. A case report. J Reprod Med. 1983;28(2):156–158.

10. Kurzel RB, Naunheim KS, Schwartz RA. Repair of symptomatic diaphragmatic hernia during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;71(6):869–871.

11. Chen Y, Hou Q, Zhang Z, Zhang J, Xi M. Diaphragmatic hernia during pregnancy: a case report with a review of the literature from the past 50 years. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2011;37(7):709–714. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0756.2010.01451.x

12. Thompson J, Le Blanc LJ. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: visceral strangulation complicating delivery. Am J Surg. 1945;67(1):123–130. doi:10.1016/0002-9610(45)90335-7

13. Pearson SC, Pillsbury SG, Mccallum M. Strangulated diaphragmatic hernia complicating delivery. J Am Med Assoc. 1950;144(1):22–24. doi:10.1001/jama.1950.62920010004006b

14. Hushlan S. Diaphragmatic hernia in pregnancy; significance and danger. Conn State Med J. 1951;15(11):969.

15. Hobbins W, Hurwitz C. Incarcerated diaphragmatic hernia of the colon occurring during pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 1953;249(19):773–774. doi:10.1056/nejm195311052491905

16. Reed MW, De Silva PH, Mostafa SM, Collins FJ. Diaphragmatic hernia in pregnancy. Br J Surg. 1987;74(5). doi:10.1002/bjs.1800740540

17. Toorians AW, Drost-Driessen MA, Snellen JP, Smeets RW. Acute hernia of Bochdalek during pregnancy. Hyperemesis for the first time in a third pregnancy? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1992;71(7):547–549. doi:10.3109/00016349209041449

18. Hill R, Heller MB. Diaphragmatic rupture complicating labor. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;27(4):522–524. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(96)70248-2

19. Ortega-Carnicer J, Ambros A, Alcazar R. Obstructive shock due to labor-related diaphragmatic hernia. Crit Care Med. 1998;26(3):616–618. doi:10.1097/00003246-199803000-00042

20. Genc MR, Clancy TE, Ferzoco SJ, Norwitz E. Maternal congenital diaphragmatic hernia complicating pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(5):1194–1196.

21. Williams M, Appelboam R, McQuillan P. Presentation of diaphragmatic herniae during pregnancy and labour. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2003;12(2):130–134. doi:10.1016/S0959-289X(02)00189-9

22. Barbetakis N, Efstathiou A, Vassiliadis M, Xenikakis T, Fessatidis I. Bochdaleck’s hernia complicating pregnancy: case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(15):2469–2471. doi:10.3748/wjg.v12.i15.2469

23. Eglinton TW, Coulter GN, Bagshaw PF, Cross LA. Diaphragmatic hernias complicating pregnancy. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76(7):553–557. doi:10.1111/j.1445-2197.2006.03776.x

24. Luu TD, Reddy VS, Miller DL, Force SD. Gastric rupture associated with diaphragmatic hernia during pregnancy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82(5):1908–1910. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.02.083

25. Pai S, Balu K, Madhusudhanan J. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia complicating pregnancy: a case report. Internet J Gynecol Obstet. 2007;9:1.

26. Rajasingam D, Kakarla A, Jones A, Ash A. Strangulated congenital diaphragmatic hernia with partial gastric necrosis: a rare cause of abdominal pain in pregnancy. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61(9):1587–1589. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2005.00763.x

27. Palanivelu C, Rangarajan M, Maheshkumaar G, Parthasarathi R. Laparoscopic mesh repair of a Bochdalek diaphragmatic hernia with acute gastric volvulus in a pregnant patient. Singapore Med J. 2008;49(1):e26–e28.

28. Sano A, Kato H, Hamatani H, et al. Diaphragmatic hernia with ischemic bowel obstruction in pregnancy: report of a case. Surg Today. 2008;38(9):836. doi:10.1007/s00595-007-3718-y

29. Hunter JD, Nimmagadda J, Quayle A. Maternal congenital diaphragmatic hernia causing cardiovascular collapse during pregnancy. Br J Hosp Med. 2009;70(3):166–167. doi:10.12968/hmed.2009.70.3.40573

30. Islah M, Jiffre D. A rare case of incarcerated bochdalek diaphragmatic hernia in a pregnant lady. Med J Malay. 2010;65(1):75–76.

31. Morcillo-López I, Hidalgo-Mora JJ, Baamonde A, Díaz-García C. Gastric and diaphragmatic rupture in early pregnancy. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2010;11(5):713–715. doi:10.1510/icvts.2010.246140

32. Ngai I, Sheen -J-J, Govindappagari S, Garry DJ. Bochdalek hernia in pregnancy. Case Rep. 2012;2012:bcr2012006859.

33. Hamaji M, Burt BM, Ali SO, Cohen DM. Spontaneous diaphragm rupture associated with vaginal delivery. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;61(8):473–475. doi:10.1007/s11748-012-0146-8

34. Kawashima K, Nakahata K, Negoro T, Nishikawa K. “Spontaneous” Rupture of the Maternal Diaphragm. Anesthesiology. 2013;118(2):445. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e31825d95ed

35. Wieman E, Pollock G, Moore BT, Serrone R. Symptomatic right-sided diaphragmatic hernia in the third trimester of pregnancy. J Soc Laparoend Surg. 2013;17(2):358. doi:10.4293/108680812X13517013318157

36. Ali SA, Haseen MA, Beg MH. Agenesis of right diaphragm in the adults: a diagnostic dilemma. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2014;56(2):121–123. doi:10.5005/ijcdas-56-2-121

37. Debergh I, Fierens K. Laparoscopic repair of a Bochdalek hernia with incarcerated bowel during pregnancy: report of a case. Surg Today. 2014;44(4):753–756. doi:10.1007/s00595-012-0441-0

38. Hernández-Aragon M, Rodriguez-Lazaro L, Crespo-Esteras R, Ruiz-Campo L, Adiego-Calvo I, Campillos-Maza J. Bochdalek diaphragmatic hernia complicating pregnancy in the third trimester: case report. Obstet Gynaecol Cases. 2015;2. doi:10.23937/2377-9004/1410057

39. Reddy M, Kroushev A, Palmer K. Undiagnosed maternal diaphragmatic hernia–a management dilemma. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):1–5. doi:10.1186/s12884-018-1864-4

40. Gorbach AC, Reid DE. Hiatus hernia in pregnancy. New Engl J Med. 1956;255(11):517–519. doi:10.1056/NEJM195609132551107

41. Craddock D, Hall J. Strangulated diaphragmatic hernia complicating pregnancy. Br J Surg. 1968;55(7):559–560. doi:10.1002/bjs.1800550717

42. Fardy HJ. Vomiting in late pregnancy due to diaphragmatic hernia. Case report. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1984;91(4):390–392. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1984.tb05930.x

43. Fleyfel M, Provost N, Ferreira JF, Porte H, Bourzoufi K. Management of diaphragmatic hernia during pregnancy. Anesth Analg. 1998;86(3):501–503.

44. Rubin S, Sandu S, Durand E, Baehrel B. Diaphragmatic rupture during labour, two years after an intra-oesophageal rupture of a bronchogenic cyst treated by an omental wrapping. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2009;9(2):374–376. doi:10.1510/icvts.2009.203075

45. Chen X, Yang X, Cheng W. Diaphragmatic tear in pregnancy induced by intractable vomiting: a case report and review of the literature. J Mat Fet Neonat Med. 2012;25(9):1822–1824. doi:10.3109/14767058.2011.640371

46. Diddle A, Tidrick R. Diaphragmatic hernia associated with pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1941;41(2):317–321. doi:10.1016/S0002-9378(41)91184-5

47. Bernhardt LC, Lawton BR. Pregnancy complicated by traumatic rupture of the diaphragm. Am J Surg. 1966;112(6):918–922. doi:10.1016/0002-9610(66)90151-6

48. Dudley AG, Teaford H, Gatewood TS. Delayed traumatic rupture of the diaphragm in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1979;53(3 Suppl):25S–27S.

49. Mitchell R, Teare A. Traumatic diaphragmatic hernia in pregnancy. South Af Med J. 1983;63(13):474.

50. Rabinovici J, Czerniak A, Rabau MY, Avigad I, Wolfstein I. Diaphragmatic rupture in late pregnancy due to blunt injury. Injury. 1986;17(6):416–417. doi:10.1016/0020-1383(86)90087-2

51. Henzler M, Martin ML, Young J. Delayed diagnosis of traumatic diaphragmatic hernia during pregnancy. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17(4):350–353. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(88)80780-7

52. Maddox P, Mansel R, Butchart E. Traumatic rupture of the diaphragm: a difficult diagnosis. Injury. 1991;22(4):299–302. doi:10.1016/0020-1383(91)90010-C

53. Lacayo L, Taveras JM, Sosa N, Ratzan KR. Tension fecal pneumothorax in a postpartum patient. Chest. 1993;103(3):950–951. doi:10.1378/chest.103.3.950

54. Dietrich CL, Smith CE. Anesthesia for cesarean delivery in a patient with an undiagnosed traumatic diaphragmatic hernia. Anesthesiology. 2001;95(4):1028–1031. doi:10.1097/00000542-200110000-00038

55. Indar A, Bornman P, Beckingham I. Late presentation of traumatic diaphragmatic hernia in pregnancy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2001;83(6):392.

56. Jai SR, Bensardi F, Hizaz A, Chehab F, Khaiz D, Bouzidi A. A late post-traumatic diaphragmatic hernia revealed during pregnancy by post-partum respiratory distress. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2007;276(3):295–298. doi:10.1007/s00404-007-0347-z

57. Riad M, Shervington J, Woodward Z. Maternal death due to ruptured diaphragmatic hernia. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;29(7):669. doi:10.1080/01443610903078888

58. DeLee S, Gilson B. Diaphragmatic hernia complicating the puerperium. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1941;41(5):904. doi:10.1016/S0002-9378(41)90889-X

59. Bourgeois GA, Hood WT. Strangulated Diaphragmatic Hernia Complicating Pregnancy: report of a Case. New Engl J Med. 1949;241(4):150–151. doi:10.1056/NEJM194907282410406

60. Wolfe CA, Peterson MW. An unusual cause of massive pleural effusion in pregnancy. Thorax. 1988;43(6):484–485. doi:10.1136/thx.43.6.484

61. Kaloo PD, Child A, Child A. Postpartum diagnosis of a maternal diaphragmatic hernia. Austra New Zeal J Obstet Gynaecol. 2001;41(4):461–463. doi:10.1111/j.1479-828X.2001.tb01333.x

62. Hamoudi D, Bouderka M, Benissa N, Harti A. Diaphragmatic rupture during labor. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2004;13(4):284–286. doi:10.1016/j.ijoa.2004.04.001

63. Hanekamp LA, Toben FM. A pregnant woman with shortness of breath. Neth J Med. 2006;64(3):84–95.

64. Agarwal P, Ash A. Gastric volvulus: a rare cause of abdominal pain in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;27(3):313–314. doi:10.1080/01443610701241183

65. Osman I, McKernan M, Rae D. Normal vaginal delivery following rupture of the maternal diaphragm in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;27(6):625–627. doi:10.1080/01443610701554247

66. Ting JYS. Difficult diagnosis in the emergency department: hyperemesis in early trimester pregnancy because of incarcerated maternal diaphragmatic hernia. Emerg Med Austral. 2008;20(5):441–443. doi:10.1111/j.1742-6723.2008.01119.x

67. Schwentner L, Wulff C, Kreienberg R, Herr D. Exacerbation of a maternal hiatus hernia in early pregnancy presenting with symptoms of hyperemesis gravidarum: case report and review of the literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;283(3):409–414. doi:10.1007/s00404-010-1719-3

68. Benson CC, Valente AM, Economy KE, et al. Discovery and management of diaphragmatic hernia related to abandoned epicardial pacemaker wires in a pregnant woman with {S, L, L} transposition of the great arteries. Congenit Heart Dis. 2012;7(2):183–188. doi:10.1111/j.1747-0803.2011.00547.x

69. Flamée P, Pregardien C. Tension gastrothorax causing cardiac arrest. CMAJ. 2012;184:1.

70. Chen Y, Bai J, Guo Y, Zhang G. The simultaneous repair of an irreducible diaphragmatic hernia while carrying out a cesarean section. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4(9):771–772. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2013.06.002

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.