Back to Journals » International Journal of General Medicine » Volume 12

Knowledge and practice of dry powder inhalation among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a regional hospital, Nepal

Authors Baral MA

Received 3 April 2018

Accepted for publication 14 June 2018

Published 24 December 2018 Volume 2019:12 Pages 31—37

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S165659

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Video abstract presented by Baral.

Views: 1291

Mira Adhikari Baral

Department of Nursing, Pokhara Campus, Tribhuvan University, Institute of Medicine, Pokhara, Nepal

Purpose: Dry powder inhalation is a cornerstone of treatment in patients with COPD. This study was undertaken to study the knowledge and practice of dry powder inhalation among such patients.

Patients and methods: The current study was a cross-sectional study conducted in Western Regional Hospital, Pokhara, Nepal. The study was conducted among 204 COPD patients (outpatients and inpatients) aged ≥20 years who had been using rotahaler, a dry powder inhaler device, and a purposive sampling technique was used. Data were collected from February 28, 2016, to March 26, 2016. A questionnaire was administered by the interviewer to assess the knowledge about dry powder inhaler (DPI) and inhalation while a Dutch Asthma Foundation observation checklist for rotahaler was used to evaluate the practice of dry powder inhalation. The collected data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and inferential statistics (chi-square test).

Results: Findings from the study showed that a low proportion of the respondents had accurate knowledge and correctly practiced inhalation technique (3.9%). However, majority of the respondents (77.5%) performed the critical steps correctly. The correct practice of dry powder inhalation was associated with younger age (p=0.008), urban residence (p=0.024), and literacy (p=0.012). The practice was comparatively more accurate among those who received practical classes/demonstration on the inhalation technique from health care providers (p<0.001).

Conclusion: Based on the study findings, it was concluded that COPD patients attending Western Regional Hospital possessed satisfactory knowledge but poor technique of dry powder inhalation. The most important modifiable factor for incorrect practice was a lack of demonstration on inhalation technique by the health care provider. Therefore, it is necessary for health care providers to supplement verbal instruction on dry powder inhalation with demonstration and re-demonstration from the patients to improve the knowledge and practice of dry powder inhalation for COPD patients.

Keywords: knowledge, practice, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, dry powder inhalation, rotahaler

Introduction

COPD is a life-threatening disease. It is a lung disease characterized by chronic obstruction of lung airflow that interferes with normal breathing and is not fully reversible. Chronic bronchitis and emphysema fall under COPD.1 It is an increasing cause of morbidity and mortality and an economic burden on the health care system.2,3 An estimated annual death rate of 3 million people (5%) occurs due to COPD, which makes it the fourth leading cause of death in the world.4 Approximately 90% of these deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries.4 By 2020, COPD is anticipated to become the third leading cause of death in the world.5 In Nepal, COPD is prevalent among 18.3% of total adults.6 Hospital-based prevalence showed that COPD comprises 43% of non-communicable disease and 2.56% of all hospitalizations in Nepal.7 Pharmacological therapies for COPD include bronchodilators (beta 2 agonists), antimuscarinic drugs/anticholinergics, corticosteroids, methylxanthines, and phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors. Among these drugs, bronchodilators, anticholinergics, and corticosteroids are best administered through aerosol therapy.5,8,9 Aerosol treatment, which is the main stay of treatment in COPD has many advantages over oral intake, as inhalation promotes the supply of drugs directly to the affected site and has fewer side effects. Moreover, the action of the drug is rapid, and a smaller dose of the drug is required to achieve a therapeutic effect.10 Inhaler devices are required to deliver the aerosol drugs to the targeted site. These include pressurized metered-dose inhalers (pMDIs), dry powder inhalers (DPIs), and mist inhalers.11 These inhalers have their own advantages and disadvantages. DPI is commonly used among patients with a higher inspiratory flow rate to disperse the drug to the targeted site. It is easy to use as no coordination is required between the activation of the inhaler and inhalation.12–14 The devices that are generally used for the inhalation of drugs among COPD patients in Nepal are DPIs, pMDI, and mist inhalers. DPIs commonly used in Nepal include rotahaler, diskus, and revolizer. Among them, rotahaler is a very commonly used DPI device. The effectiveness of the inhaled drug depends on how correctly one inhales aerosol drugs through the inhaler device. An incorrect inhalation technique results in inadequate drug delivery to the lungs and hence worse COPD outcomes.2,3,15 Although a correct technique for inhalation is necessary to achieve the effectiveness of the drug, a large proportion of patients undergoing inhalation treatment through the use of a rotahaler do not use the correct inhalation technique. A systematic study has shown that poor inhalation technique ranges from 4% to 94%.16 The resultant outcome is frequent COPD exacerbations, hospital admissions, and economic burden.2,3,15,16 Studies have shown that various factors affect the inhalation technique of patients. These include their age, sex, educational status, occupation, area of residence, duration of disease, associated comorbid conditions, poor inhalation instruction, and poor monitoring of the inhalation technique of the patients.17–20

Although the rotahaler is a preferred DPI device among physicians in Nepal, limited attempts have been made to study how well COPD patients use the device. Moreover, these studies have been conducted at the central level. The increasing burden of COPD in Nepal and the escalating use of DPI for its treatment without due consideration to evaluation of the patients’ skill in regard to its correct use has become a serious concern in creating an effective treatment of COPD and achieving goals of national policy regarding a 25% reduction in the burden of non-communicable disease by 2020.

With this view of the aforementioned facts and interest in the topic, the present study was undertaken to assess the level of knowledge and practice of dry powder inhalation among COPD patients in a regional-level hospital.

Patients and methods

Research design: cross-sectional study

Study setting

The study site was Western Regional Hospital, which is a government hospital of Nepal that is located in Ramghat, Pokhara. It is a 350-bedded hospital and is also a tertiary hospital for the western region of Nepal (16 districts). This setting was selected for the study because of its feasibility and approachability. Moreover, it serves population from 16 districts, which increase the generalizability of the result.

Study design and study population

A hospital-based cross-sectional study was conducted. The study population was the patients who were those diagnosed with COPD (post-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1] <80% and the ratio of FEV1 to forced vital capacity <.070 on spirometry after the inhalation of bronchodilator) by physicians whose medical examination card notes the final diagnosis as COPD and attending medical outpatient department (OPD) or those admitted in medical ward of Western Regional Hospital aged ≥20, and who had been taking dry powder inhalation with a rotahaler as the treatment prior to the date of data collection. From these patients, those who did not consent to participate in the study and/or who had other obstructive diseases (asthma, bronchiectasis, and cystic fibrosis) were excluded from the study.

Sample size and sampling procedure

The sample size was based on a single population estimation formula.21 Based on the findings in Tribhuvan University (TU) Teaching Hospital, Nepal, the percentage of patients who demonstrated a correct inhalation technique was 14%.18 Assuming the prevalence of correct DPI (rotahaler) use among COPD patients, with allowable error of 5% at 95% CI, and adding 10% non-response rate, the final sample size was 204.

Western Regional Hospital was purposively selected as the study site. A purposive sampling technique was used and focused on the sampling of COPD patients. Adult patients diagnosed COPD, who had been using a rotahaler since the last 1 month were identified using the examination card and the laboratory and radiological findings of the patients. They were then consecutively selected and enrolled in the study.

Research instrument

An interviewer-administered questionnaire was used to collect information on socio-demographic variables, and knowledge on safe handling of the rotahaler while an observation checklist was adapted from Dutch Asthma Foundation to examine the practice of the rotahaler. The questionnaire was developed by the researcher herself with help from an extensive study, consultation with peers, and chest physicians.

The content validity of the instrument to assess the inhalation technique was ascertained by adopting the standard checklist by the Dutch Asthma Foundation after intense study and consultation with peers and medical consultants. Likewise, the content validity of the questionnaire was ascertained by constructing the tool after intense study, consultation with peers, and chest experts. An effort was made to make questions clear, set in an orderly manner, and easy to understand. Questionnaire was prepared in the English language and further translated into the Nepali language by the researcher; cross-checked by bilingual expert; the questionnaire was then back-translated again to English by a bilingual expert to maintain stability. Pre-testing of the instrument was conducted on 21 COPD patients in Bharatpur Hospital who met the sample criteria to identify the clarity, adequacy, and consistency of the tool.

The reliability analysis of the tool was performed by calculating Cronbach’s α value. The Cronbach’s α value of the questionnaire was 0.89.

Data collection procedure

Data were collected from February 28, 2016, to March 26, 2016 by the researcher herself. An exit interview technique was adopted for data collection. The patients who exited from the OPD and who were COPD patients who had been using a rotahaler were identified through the examination card and diagnostic tests carried out. The purpose of the study was explained, and informed verbal and written consent was collected with information about the nature of the study and the participants’ role in the research. Finger prints were taken from the illiterate respondents after the verbal consent. The questionnaire was administered by the interviewer in a separate room in the OPD (between the OPD time of 9 am and 2 pm). Regarding knowledge, the frequency of correct answer on each question was given the score of 1. Then, assessment of the dry powder inhalation technique was conducted using the rotahaler with placebo rotacaps in the same room.

A similar assessment was carried out in the ward at the bedside of the patients (before 9 am and after 2 pm). Practice was examined using the rotahaler checklist developed by the Dutch Asthma Foundation. The performance of each of the steps of rotahaler use was labeled a correct inhalation technique if the respondent correctly performed each of the steps of the checklist. The performance was labeled incorrect if the patient could not perform the steps correctly and/or missed some of the steps. After examination of the inhalation technique, the incorrect method adopted by the patient was explained to the patient. After that, the patients were shown a video of the correct inhalation technique.

Data processing and analysis

The collected data were organized, coded, and entered in SPSS software, version 16. The data were analyzed by using descriptive statistics, such as frequency, percentage, mean, and SD to assess the socio-demographic information, knowledge, and practice of rotahaler. Inferential analysis was conducted using a chi-square test to assess the association of practice of rotahaler with socio-demographic characteristics and health care provider-related aspects. The level of significance was considered at 5% with p<0.05 and a 95% CI.

Regarding knowledge, the frequency of correct answer on each of the questions was given the score of 1 and converted into a percentage. Practice was measured on the basis of correct completion of sequential steps for dry powder inhalation by using rotahaler checklist. The performance of dry powder inhalation was labeled a correct inhalation technique if the respondent correctly performed all of the steps of the checklist. The performance was labeled incorrect if the patient could not perform any or some of the critical and/or general steps.

Ethical consideration

The study was conducted after the approval of the proposal from the Institutional Review Board, Institute of Medicine (IOM) and the executive director of the Western Regional Hospital. No vulnerable members were included in the study. Informed verbal and written consent was acquired prior to data collection. Written consent from the illiterate population was taken through collection of a thumb print. Data were collected in a separate room nearby OPD to maintain privacy. There was no risk involved to the participants. The participants benefited by being provided with an opportunity to observe correct inhalation technique in a video. Confidentiality of the respondents was maintained by coding the answers. Collected information was used only for the purpose of the study, and the information was not misused for other purposes. Regarding safety considerations, no harmful treatment was conducted on the respondents.

Results

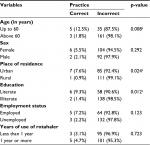

Background characteristics of respondents

The study showed that nearly half (49.5%) of the rotahaler users belonged to the 61–70 years age group. The overall mean and SD of the age of those users was 67.22+9.92. More than half of the COPD patients using rotahalers were females (53.9%) and from rural areas (54.9%). More than two-thirds of them were illiterate (68.6%) and unemployed (66.2%). Among the literates, the maximum number (42.2%) of DPI users had basic education. The majority (48%) of the respondents had used the rotahaler for less than a year (Table 1).

| Table 1 Background characteristics of patients using rotahaler Note: Mean age ± SD (in years)=67.22±9.92. |

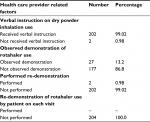

Health care provider-related factors affecting knowledge and practice of dry powder inhalation among COPD patients

Regarding instruction, nearly all (99.02%) of the rotahaler users got verbal instruction regarding the use of the rotahaler. However, only 13.2% of the respondents had observed a demonstration of dry powder inhalation from health care providers. Less than 1% of the respondents were given an opportunity for re-demonstration and were observed doing re-demonstration by the care providers at their first use of the rotahaler; however, none of them were rechecked on their inhalation technique during their follow-up visits (Table 2).

| Table 2 Health care provider-related factors affecting knowledge and practice of dry powder inhalation among COPD patients |

Knowledge about DPI and inhalation among COPD Patients

The majority of the DPI users (89.2%) had correct knowledge about the storage of rotacaps. They were aware that rotacaps should be kept in a cool place away from moisture, and four-fifths of them (80.4%) were aware that they should take a slow deep breath while inhaling the drug. However, only 11.7% of them possessed the correct knowledge on holding breath for 10 seconds after deep inhalation of the drug (Table 3).

| Table 3 Knowledge about dry powder inhalation among COPD patients |

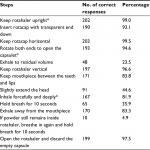

Stepwise practice of dry powder inhalation through the rotahaler among COPD patients

Regarding practice, the item most correctly performed by the rotahaler users was keeping the Rotacap horizontal (99.5%) followed by keeping the rotahaler upright (99%) and opening the rotahaler and discarding the empty capsule (97.5%). In contrast, the least correctly performed step was breathing in again and holding the breathe for 10 seconds (4.9%), which is also a combination of steps. In regard to the single step, the most frequently committed error was exhaling to residual volume (76.5%) followed by holding the breath for 10 seconds (64.1%) (Table 4). Regarding the essential steps, the majority of the COPD patients correctly performed the step “Keep rotahaler upright” (99%) followed by “Rotate both ends to open the capsulet” (94.6%) (Table 4). Most of the patients (77.5%) performed all the essential items correctly. However, 22.5% of them could not correctly perform 1 or more of the crucial steps. In respect to all the steps of the dry powder inhalation, a minority (3.9%) of the patients demonstrated the use of the rotahaler correctly, while most of them (96.1%) performed the steps incorrectly (Table 4).

| Table 4 Stepwise practice of dry powder inhalation through the rotahaler among COPD patients Note: *Denotes essential steps. Until these steps are performed, drugs cannot enter to the lungs. |

Association of background variables with practice of dry powder inhalation

The practice of dry powder inhalation was statistically significant with age of the rotahaler users (p=0.008). Patients up to the age of 60 years demonstrated the correct use of the rotahaler compared with those >60 years of age. Similarly, practice was significantly associated with the place of residence (p=0.024). Those who were from urban areas practiced inhalation technique more correctly than those from rural area. Education of the patients was significantly associated with practice of rotahaler; literate patients performed the inhalation technique more correctly than illiterate ones (p=0.012). However, no significant association was observed in the practice of DPI in terms of sex (p=0.292), employment status (p=0.123) and years of use of rotahaler (p=0.723) (Table 5).

| Table 5 Association between background variables and the practice of dry powder inhalation among COPD patients Note: ap<0.05 (statistically significant). |

Association of health care provider related factors with practice of dry powder inhalation

There is statistically significant association of practice of dry powder inhalation with a demonstration of dry powder inhalation by health care providers (p=0.001). Those who received a demonstration on the use of the rotahaler from health care providers performed the inhalation more accurately than those who did not (Table 6).

| Table 6 Association between health care provider-related factors and the practice of dry powder inhalation among COPD patients Note: aP<0.05 (statistically significant). |

Discussion

In this study, the results regarding knowledge and practice are quite alarming, as the majority of the rotahaler users possessed satisfactory knowledge on the rotahaler and its use, whereas 96.1% of those users performed the inhalation technique incorrectly. This could have occurred because of the poor instruction from health care providers, lack of questioning attitude in Nepalese patients, and their negligence or inability to read the instruction leaflet provided in the drug box.

The majority of rotahaler users (96.1%) could not correctly complete all the steps of dry powder inhalation through the rotahaler. Regarding the essential items, 77.5% of the users performed all the essential steps correctly. The least correctly performed step according to the Dutch Asthma Foundation checklist for rotahaler was while taking the second breath, which is a combination of the following steps: exhaling to residual volume, keeping mouthpiece between teeth and lips, breathing in again, and holding breath for 10 seconds (4.9%). Regarding the single step, most commonly committed error was not being able to exhale to residual volume (76.5%). Similar results have been reported in other studies.18,19,22,23 The second most frequently committed error was not being able to hold one’s breath for 10 seconds (64.1%). This result can be attributed to poor instruction, and a lack of supervision and follow-up check on dry powder inhalation technique by health care providers, the quality of instruction from the health care providers, and their emphasis on item skills.

In regard to the essential items, the most frequently committed error was in the step, inhale forcefully and deeply.18,23,24 This error halts the deposition of inhaled drug into the lungs, resulting in poor treatment outcome. However, this result contrasts with the study by van der Palen et al, which showed that the most frequent error was keeping the rotahaler upright.22 This inconsistency may be associated with the quality of instruction from the health care providers and their emphasis on item skills.

Regarding practice, the correct use was associated with younger age (p=0.008),18,24–26 an urban area of residence (p=0.024),20 and literacy (p=0.012).18,20,26–29 Poor coordination and decline in cognition with increasing age may have resulted in a poor inhalation technique. Therefore, the elderly population required frequent checking and training of inhalation technique. Similarly, the quality of health care services may be poor among the rural residents, leading to poor knowledge and practice of inhalation technique. In regard to education, higher level of education may have increased better understanding, confidence, and critical analysis, which, in turn, could enhance better learning of the inhalation techniques.

Similarly, poor inhalation technique in this study was significantly associated with no practical class/demonstration on dry powder inhalation by health care providers (p<0.001).19,20,22,24,25,27,28,30 This result signifies the need for health care personnel to practically demonstrate the technique for dry powder inhalation and conduct re-demonstrations from the patients at each visit to ensure that the patients are taking the drugs accurately, and the best results of the treatment can be achieved.

Conclusion

It is concluded that COPD patients using the rotahaler and attending Western Regional Hospital possessed a satisfactory level of knowledge and poor practice of dry powder inhalation. Regarding practice, the most commonly performed error among rotahaler users is not exhaling prior to inhalation followed by the inability to hold one’s breath for 10 seconds. However, practice of essential items of the inhalation procedure is better compared with the practice of all of total items.

A poor practice of dry powder inhalation is linked to the elderly age group, illiteracy, rural area of residence, and no demonstration on the inhalation technique by health care providers. The poor level of knowledge and practice of dry powder inhalation thus revealed a serious concern to be considered for the effective treatment of COPD.

Limitations

This study was a cross-sectional small-scale study conducted by adopting a nonprobability sampling technique among COPD patients who attended a single setting. Therefore, this result has limited generalizability. Moreover, this study did not include drug-specific concerns of care in the assessment of knowledge because of the constraints of time. Therefore, this study cannot be generalized to patients using corticosteroids as their inhaled aerosol drugs.

Implications

The result of this study can be a guide to health care providers to improve their instruction on dry powder inhalation, including the demonstrations focused on the frequently committed errors. This result can also be helpful for hospitals to develop and enforce a health teaching protocol for COPD patients, which includes clear instruction and demonstration and re-demonstration on the use of the rotahaler.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge Sashidhar Baral, Yam Bahadur Rana, Manoj Koirala, and Bishow Baral who helped with the translation of the tool, and Bikash KC for assistance in data analysis. Thanks is also given to Bhagwati KC, Sarala Shrestha, and all the faculty of TU, IOM, Pokhara Campus, as well as those who helped me in this study. This study was self-funded by the researcher.

Author contributions

The author has herself contributed to developing the proposal, collecting the data, analyzing the data, writing the report, gave final approval of the version to be published. The author is accountable for all aspects of work.

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

World Health Organization. Chronic Respiratory Diseases. Geneva: Switzerland; 2017. Available from: http://www.who.int/respiratory/copd/definition/en/. Accessed May 15, 2017. | ||

Guarascio AJ, Ray SM, Finch CK, Self TH. The clinical and economic burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the USA. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;5:235–245. | ||

Blasi F, Cesana G, Conti S, et al. The clinical and economic impact of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a cohort of hospitalized patients. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e101228. | ||

World Health Organization. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Fact sheet N°315. Geneva: Switzerland; 2015. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs315/en/. Assessed March 2, 2016. | ||

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Pocket Guide To COPD Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention: A Guide for Health Care Professionals; 2017. | ||

World Health Organisation. Chronic Respiratory Diseases. Switzerland: Geneva; 2017. Available from: http://www.who.int/gard/publications/chronic_respiratory_diseases.pdf. Assessed March 17, 2017. | ||

Bhandari GP, Angdembe MR, Dhimal M, Neupane S, Bhusal C. State of non-communicable diseases in Nepal. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:23. | ||

Alifano M, Cuvelier A, Delage A, et al. Treatment of COPD: from pharmacological to instrumental therapies. Eur Respir Rev. 2010;19(115):7–23. | ||

Montuschi P. Pharmacological treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2006;1(4):409–423. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2707800/. Assessed December 13, 2016. | ||

Bonini M, Usmani OS. The importance of inhaler devices in the treatment of COPD. COPD Res Pract. 2015;1(1):9.0. | ||

National Asthma Council Australia. Australian Asthma Handbook: Inhaler devices and technique; 2017. Available from: http://www.asthmahandbook.org.au/management/devices. Assessed August 10, 2017. | ||

Schwarz E, Redeker M, Mohrlang C, et al. Criteria Used by German Pulmonologists for the Selection of an Inhaler. Value Health. 2016;19(7):A703–A704. | ||

Virchow JC. Guidelines versus clinical practice--which therapy and which device? Respir Med. 2004;98 Suppl B:S28–S34. | ||

Dolovich MB, Dhand R. Aerosol drug delivery: developments in device design and clinical use. Lancet. 2011;377(9770):1032–1045. | ||

Lavorini F, Mannini C, Chellini E. Challenges of inhaler use in the treatment of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2012;7:495–502. | ||

Lavorini F. The challenge of delivering therapeutic aerosols to asthma patients. ISRN Allergy. 2013;2013:102418. | ||

Hesselink AE, Penninx BW, Wijnhoven HA, Kriegsman DM, van Eijk JT. Determinants of an incorrect inhalation technique in patients with asthma or COPD. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2001;19(4):255–260. | ||

Pun S, Prasad GK, Bharati L. Assessment of inhalation techniques in copd patients using metered-dose inhaler and rotahaler at a tertiary care hospital in Nepal. Int Res J Pharm. 2015;6(5):288–293. | ||

Shrestha S, Sapkota B, Ghimirey A, Shakya R. Impact of counseling in inhalation technique (rotahaler) in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Int Res J Pharm. 2013;3(3):442–449. | ||

Aydemir Y. Assessment of the factors affecting the failure to use inhaler devices before and after training. Respir Med. 2015;109(4):451–458. | ||

Pant PP. Biostatistics. Bhotahity, Kathmandu: Vidarthi Pustak Bhandar; 2012. | ||

van der Palen J, Klein JJ, Kerkhoff AH, van Herwaarden CL. Evaluation of the effectiveness of four different inhalers in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 1995;50(11):1183–1187. | ||

van Beerendonk I, Mesters I, Mudde AN, Tan TD. Assessment of the inhalation technique in outpatients with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease using a metered-dose inhaler or dry powder device. J Asthma. 1998;35(3):273–279. | ||

Sapkota D, Amatya YR. Assessment of rotahaler inhalation technique among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a teaching hospital of Nepal. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2017;5(1):11–17. | ||

Ansari M, Rao BS, Koju R, Shakya R. Impact of pharmaceutical intervention on inhalation technique. Kathmandu University Journal of Science, Engineering and Technology. 2005;1(1). | ||

Chorão P, Pereira AM, Fonseca JA. Inhaler devices in asthma and COPD--an assessment of inhaler technique and patient preferences. Respir Med. 2014;108(7):968–975. | ||

Melani AS, Bonavia M, Cilenti V, et al. Inhaler mishandling remains common in real life and is associated with reduced disease control. Respir Med. 2011;105(6):930–938. | ||

Sestini P, Cappiello V, Aliani M, et al. Prescription bias and factors associated with improper use of inhalers. J Aerosol Med. 2006;19(2):127–136. | ||

Arora P, Kumar L, Vohra V, et al. Evaluating the technique of using inhalation device in COPD and bronchial asthma patients. Respir Med. 2014;108(7):992–998. | ||

Manandhar A, Malla P, Nijan U. Assessment of inhalation technique and the impact of intervention in patients with Asthma or Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in Nepal. World J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2016;5(2):619–681. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.