Back to Journals » Advances in Medical Education and Practice » Volume 11

Knowledge and Attitudes Towards Abortion and Euthanasia Among Health Students in Papua New Guinea

Authors Kolodziejczyk I , Kuzma J

Received 9 September 2020

Accepted for publication 23 November 2020

Published 15 December 2020 Volume 2020:11 Pages 977—987

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S281199

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Prof. Dr. Balakrishnan Nair

Iwona Kolodziejczyk,1 Jerzy Kuzma2

1Centre for Learning and Teaching, Divine Word University, Madang, Papua New Guinea; 2Medical Department, Divine Word University, Madang, Papua New Guinea

Correspondence: Iwona Kolodziejczyk

Centre for Learning and Teaching, Divine Word University, P.O. Box 483, Madang 511, Papua New Guinea

Tel +675 70407734

Email [email protected]

Purpose: The purpose of this study was to explore knowledge and attitudes of health program students towards ethical issues pertaining to the beginning and the end of human life, and associations between these attitudes and demographic variables.

Participants and Methods: The study took a mixed-method approach with self-administered survey questionnaires and in-depth interviews. A total of 88 students participated in the survey, and 10 students participated in interviews. The study was conducted among students in the Health Extension Program at a Christian university in Papua New Guinea.

Results: Students showed a higher acceptance of abortion than euthanasia. More year-4 students presented significantly deeper knowledge of euthanasia and abortion compared to year-1 students. There were no gender differences regarding knowledge and attitude towards these two bioethical issues. The majority of students opposed the idea of women’s right to abortion, which is attributed mainly to socio-cultural reasons. The qualitative analysis indicated a very strong perception that having children ‘defines’ womanhood and also revealed general disapproval of any form of euthanasia. A low level of acceptance of various forms of euthanasia is associated with a respect for older people in Melanesian society and beliefs that ancestors’ support is required for achieving prosperity in life.

Conclusion: The study offered a comprehensive description and analysis of students’ knowledge and attitudes towards ethical issues pertaining to the beginning and the end of human life. Presented a low level of knowledge towards bioethical issues, together with a small proportion of the knowledge gained from lectures and tutorials, indicated inadequate teaching of bioethics and calls for further improvement. In the perspective of rapid social and cultural changes in the Papua New Guinea society, further studies on changing attitudes towards bioethics issues would be valuable.

Keywords: bioethics education, health students, abortion, euthanasia, developing country

Introduction

Health professionals encounter and have to solve ethical issues in day-to-day practice. Their knowledge and attitudes towards abortion and euthanasia are influenced by their education as well as the cultural values of the society and religious beliefs.

Bioethical Study and Students’ Attitudes Towards Abortion and Euthanasia

The importance of bioethics in medical programs is well acknowledged.1–6 Ranasinghe et al2 accentuate that comprehensive ethical training is necessary to prepare future health workers to anticipate and make decisions when faced with ethical dilemmas in daily practice. Woloschuk et al7 observe that knowledge obtained during years of study impacts attitudes and in turn, attitudes guide behavior. In addition, while students progress in their years of study, they are expected to further develop their moral reasoning4 and equip themselves with tools “to analyze ethical issues and formulate a cogent and well-defended position”5 (p2). Casini et al8 describe the medical practice as “a minefield of ethical challenges” (p. 364) where often life and death decisions have to be reached quickly. Years of training in bioethical issues should prepare students to constructively identify, evaluate and resolve bioethical issues that arise in clinical practice.

Two vital bioethical issues that future health officers will deal with are issues pertaining to the beginning and the end of life. Understanding what the knowledge and attitudes towards these issues are among students entering health programs may help to better shape health programs’ curricula to better equip them for inevitable future dilemmas. Studies done in various parts of the world draw a broad picture of medical students’ attitudes towards these issues.

Reports from various parts of the world show differences in medical students’ attitudes towards abortion. In Jamaica, 64% of the medical students have a positive attitude toward abortion.9 In Brazil, 51% accept abortion for genetic reasons, and 23% accept abortion for failed contraception.5 In Spain, a pro-abortion attitude was declared by 44%.10 Studies done among Polish students show high acceptance of abortion for legalized reasons: 90% when pregnancy is an effect of crime; 85% when pregnancy threatens mother’s life and 80% when a severe defect in the fetus is detected; total prohibition of abortion was supported by 4% of the students.11 Similarly, South African students agree to legalization of abortion if a woman’s physical or mental health is endangered by pregnancy (83% and 69%, respectively); if the fetus has a congenital defect or malformation (65%); if the pregnancy was the result of rape or incest (64% and 52%, respectively); and if a woman is not married (62%); 22% of the students are against abortion regardless the reason.12

Similarly, various attitudes are reported in the studies on issues pertaining to the end-of-life. Acceptance of euthanasia was declared by 41% of the medical students in Brazil.5 Euthanasia under some circumstance (ie terminal illness) was supported by 52% of the Greek students13 and 80% of the UK students.14 Interestingly, studies done in one country over extended periods of time demonstrate changes in students’ attitudes. In Poland, research in 2005 and 2009 recorded a drastic change in students’ attitudes towards euthanasia with 82% and 58% respectively definitively rejecting the possibility of performing the act of euthanasia while 6% and 29% respectively were undecided; in 2013, 88% of the medical students declared that they would not perform a euthanasia act, but at the same time almost 60% supported the legalization of euthanasia if certain criteria are met.11

The major factors associated with variations in medical students’ attitudes towards issues pertaining to the beginning and the end of life are cultural values and religious beliefs,5,10,14 medical school characteristics including type of university,5,15 the year of study6,11 and gender.13,14

As reminded by Bamberger and Guinan,16 the development of medical ethics commenced from the time of Hippocrates (the Hippocratic oath). A number of important socio-political events of the second half of the 20th century led to the development of bioethics and adoption of Codes of Medical Ethics8 that are supposed to be adhered to by all in the health profession. Without disputing the importance of universal norms, globalization and immigration have led to the realization of differences in the practice of medicine in different parts of the world as well as an appreciation of culturally driven responses to bioethical issues, including issues pertaining to the beginning and the end of human life.17 Religious beliefs and cultural values are recognized as important factors shaping future health professionals’ attitudes to bioethical issues.5 Thus, the next section discusses how culture and personal beliefs guide health professionals’ responses to the issues of abortion and euthanasia.

Social Values and Beliefs and Doctors’ Attitudes to Abortion and Euthanasia

Doctors’ attitudes on the ethical issues pertinent to the beginning and end-of-life are associated to values, beliefs and the philosophy of life prevalent in all societies but can vary from country to country. To illustrate this, there is a difference between German and Israeli perspectives of end-of-life care. The German accentuates the doctor’s duty to respect the patient’s autonomy and right to self-determination, while the Israeli concentrate on the doctor’s duty to respect the sanctity of life.18 Acceptance of euthanasia among doctors working under different circumstances and socio-cultural settings also varies significantly. The rates of acceptance for euthanasia internationally range from 1% in Japan,19 9% in Nepal,20 9.8% in Hawaii,21 15% in Sudan,22 30–39% in the UK,23,24 and over 40% in France, Switzerland and Canada.25–27 A survey among physicians in nine European countries and Australia showed that 70–99% would be willing to withdraw chemotherapy and intensify symptomatic treatment at patients’ requests. About half would be willing to deeply sedate patients to alleviate suffering until the patient’s death. Generally, doctors are considered to be less inclined to undertake active steps leading to patient death.28

The Cultural Context of the Study

In Melanesian cultures, older members of the community are often treated with high respect. Grown children have an unquestioned duty to provide for their aged parents. This moral obligation is enforced by beliefs in dead ancestors living in the spirits world and that to maintain good relations with the ancestor living in a world of spirits is an integral part of living in harmony with the whole cosmos.29 Hence, it would appear to be at odds with traditional Melanesian cultures. Regarding the ethical issues pertaining to the beginning of life, in various ethnic groups, there were reports of traditional acceptance of abortive procedures (using herbs or jumping) even to the degree of killing a new-born baby in the case of extramarital relations or twins.30 Despite official illegality of abortion in Papua New Guinea (PNG), there have been reported cases of using both modern and traditional methods of abortion.31–33 Thus, both in the past and present, there has been some degree of its acceptance for abortion in Melanesian culture.33

In PNG, rapid social change and development in medicine are bringing some of these ethical issues such as contraception, abortion, prolongation of life for critically ill and unjust distribution of resources in health to the forefront of social debate. Health workers in PNG are likely to become key stakeholders in the bioethical debate in the country. Yet, the authors are not aware of any study on the knowledge, attitudes and values connected with bioethical issues among health students or personnel in PNG. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to explore knowledge and attitudes of health program students at one university in Papua New Guinea towards the beginning and end-of-life bioethical issues as well as possible relations between the attitudes and as identified in literature demographic variables.

The purpose of the study was trifold; to determine the variability of attitudes of health students on abortion and euthanasia, to explore the association between demographic factors and attitudes towards abortion and euthanasia, and to examine the relationship between the year of the study and attitudes.

Participants and Methods

A convergent parallel mixed-methods design was used to answer the research questions guiding this study.34 As entailed by this approach, qualitative and quantitative data were collected concurrently, analyzed independently, and results were interpreted together.

Prior to actual data collection, a small pilot survey (10 questionnaires and two interviews) was conducted to validate the data collection tools. A pilot study checked for appropriateness and understanding, and revisions were made to improve the clarity of wording in questionnaire and interview protocol questions, and flow of the instrument. Then, quantitative data were collected from health students through a self-administered questionnaire. The questionnaire consisted of the following parts: demographic features including the level of religiosity, knowledge of the issues, and attitudes towards abortion and euthanasia.

The qualitative data were collected by in-depth interviews conducted among the same health student participants. Owing to the sensitivity of the subject matter, and respect for the privacy of participants, individual interviews were deemed the most appropriate method for qualitative data collection. It has also been suggested that qualitative research is required to better understand participants’ views. Interviewers, who have experience in qualitative research methods, conducted the interviews in English. The duration of the interview was approximately half an hour and was held in a private setting. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim for textual analysis.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee at DWU. The study adhered to the principles of the Helsinki Declaration. There was no potential harm caused to participants, and confidentiality and anonymity were safeguarded. Written informed consent was obtained from all interviewees.

The study was conducted at a Christian university in Papua New Guinea. The participating students were studying in the Health Extension Program, which prepares them to become primary clinical workers in rural areas. Cluster sampling was deemed appropriate for quantitative study as it involved student cohorts which are “natural groupings of people”35 (p1) in the educational context. To be able to explore if the knowledge and attitude about bioethical issues change through the years of study, all students in the first and the last year of studies were invited to participate. A total of 88 students participated in the survey; 46 of them from year-1 and 42 from year-4.

In the qualitative strand, a self-selection sampling method was used.36 During the distribution of the questionnaire, students were informed about the qualitative study and invited to participate in the interviews. Ten students volunteered to discuss their attitudes and traditional perspectives on abortion and euthanasia. Participants of our study were from a Christian university which understandably raises some concerns regarding selection bias.

All quantitative data were recorded and analyzed with SPSS 16. The Chi-square test for independence was used to determine whether there was an association between independent categorical variables. The variables measured included sex, age, year of study, level of religiosity, and knowledge on abortion and euthanasia. A p-value of less than 0.05 was deemed significant.

The qualitative data were analyzed using a thematic analysis approach. Initial categories for analyzing data were drawn from the interview guide, and themes and patterns emerged after reviewing the data. The computer software package QDA Minor Lite was used to facilitate sorting and data management. The transcripts were coded by the research team and then cross-checked for code variations. The data were then reviewed for significant trends, and cross-cutting themes were identified. Triangulation of the data from the quantitative and qualitative strands was performed at the inference phase.

Results

Both qualitative and quantitative strands of the study provided the data to explore different aspects of PNG health students’ attitudes and knowledge pertaining to the beginning and the end-of-life issues.

As indicated, a total number of 88 students took part in the study. Table 1 outlines several demographic features of the sample.

|

Table 1 Demographic Features of the Study Sample |

Analysis of the collected data included inquiry along with demographic features as reported in the following sections.

Health Students’ Knowledge

A twofold approach was used to create a full profile of health students’ knowledge about the beginning and the end-of-life issues: first, they were asked about the perception of their knowledge and then their actual knowledge was tested by asking them to associate terms like “euthanasia”, “passive euthanasia”, and “physician-assisted suicide” with provided definitions. Table 2 shows how students across both groups (year-1 and year-4) assessed their knowledge about abortion and euthanasia.

|

Table 2 Health Students’ Perception of Knowledge About Issues Pertaining to Beginning and End-of-Life |

Generally, year-4 students perceived their knowledge higher in all items compared to year-1 students. However, Chi-square test showed statistically significant difference in knowledge perception between year-1 and year-4 with regards to euthanasia (χ2(3) = 14.056; p = 0.003) and abortion (χ2(3) = 8.326 p=0.04) (Table 2).

Considering that the term “euthanasia” could be viewed as a “novelty” in medical ethics in PNG, participants were tested on their actual knowledge of different aspects of the term. Thirty-two percent of participating students admitted that they do not know what euthanasia is, and only 3.6% declared they know a lot about it. When testing their actual knowledge, questions differentiated between different forms of euthanasia (Table 3).

|

Table 3 Health Students’ Knowledge About Some Issues Pertaining to End-of-Life |

There were no differences between year-1 and year-4 students and between genders in their actual knowledge about different forms of euthanasia.

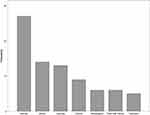

When asked about the main source of knowledge about bioethical issues (Figure 1), the students chose the internet (31%; n=27) and books (16%; n=14). A lecture, as the main source of knowledge, was chosen only by 13 participants (15%). Interestingly, there were differences in terms of the main source of knowledge about bioethical issues between different levels of study. Although the internet was considered a first choice among student at both levels, it was the first choice of almost half of year-4 students (45%) and only the fourth choice of year-1 (22.5%). On the other hand, church played a more dominant role for the students in year-1 of which 18% chose it as the primary source of knowledge compared with only 5% in year-4.

|

Figure 1 Sources of knowledge about bioethical issues among health students in Papua New Guinea. |

Health Students’ Attitudes Toward Bioethical Issues

Students were asked about their attitudes toward bioethical issues pertaining to the beginning and the end of life as well as to some ethical issues that they will face in their professional practice. Different issues are presented separately to allow a closer analysis of the results.

Students’ Attitudes Toward Bioethical Issues Pertaining to the Beginning of Life

As presented in Table 4, out of the number of issues pertaining to the beginning of human life, the majority of students (70.5%) opposed the idea of women’s right to abortion because of social reasons.

|

Table 4 Health Students’ Attitudes Toward Bioethical Issues Pertaining to the Beginning of Life |

Further analysis with Pearson Chi-square test showed that there were significant differences in attitudes towards some of the issues pertaining to the beginning of life between the students in the first and the fourth years of study. More of year-4 (67%) than of year-1 (39%) would agree that abortion should be allowed when pregnancy is threatening mother’s life (χ2=11.07; p=0.01; two sided). Similarly, more of year-4 students (48%) than year-1 (31%) would agree that abortion should be allowed when pregnancy is the result of rape or abuse (χ2=10.18; p=0.02; two sided). Twenty-six percent of year-4 students compared to 11% of year-1 students would agree that abortion should be allowed because of the mother’s mental sickness (incapacities) (χ2=7.65; p=0.05; two sided).

No gender differences were found in relation to students’ attitudes toward bioethical issues pertaining to the beginning of human life.

Among those who were uncertain if abortion should be allowed when pregnancy is a risk to mother’s health, the majority would allow it only if there was a risk of mother’s death; two participants declared that they would allow a mother to make a decision.

The qualitative analysis provided further insights into the quantitative finding in relation to students’ attitudes toward bioethical issues pertaining to the beginning of life. The majority of those who opposed the idea of a woman’s right to abortion because of a social reason used powerful language calling abortion “a murder or killing an innocent life” (year-4 male student). It has been noted that those who used such strong language indicated that the primary source of their knowledge about bioethical issues was derived from church services. Other students described a child as innocent and a gift from God. Yet others supported their argument that abortion for social reasons is unethical because it is against the Bible and God’s law. To better understand such argumentation, it should be pointed out that all participants except for one considered themselves as believers; within this group 36% described themselves as active in their churches, following their faith and church rules and principles while 60% said they occasionally attend the church services and sometimes do not follow the rules and principles of their religion.

Other arguments against abortion refer to the students’ family values. One of the female students said “Having a child will show my love for my husband and for my family. By having a child, we are bringing pride to a family”.

However, even those who said that they would never abort their own child were willing to perform an abortion in the case of pregnancy resulting from rape.

Reflecting on the perception about abortion by their generation and by that of their parents, the interviewees thought they were different. They admitted that technology and especially the internet plays a vital role in creating their view about the world. One of the female students reported: “The past generation maintained their culture and their beliefs. They were strong. As they grew in the village, they all knew what was right and what was wrong. They did not have situations of unwanted pregnancies. But these days, we have these unwanted pregnancies because of how we think, we are getting ourselves into anything we want to do without considering that we have our cultures and our belief“.

Students’ Attitudes Toward Bioethical Issues Pertaining to the End-of-Life

Generally, more than half of the students opposed most of the questions asked about forms of euthanasia and assisted suicide (Table 5). Some of the students provided explanations for their choices. The two most common were: ending someone’s life is 1) murder and against God’s law, and 2) against professional ethics.

|

Table 5 Health Students’ Attitudes Toward Bioethical Issues Pertaining to the End-of-Life |

However, there seems to be uncertainty as to how to react to the idea to perform euthanasia on terminally sick patients upon their or their family’s request. Only 43% were against the idea, and 30% were undecided. The most common explanations for their choice of “depends” were “too much suffering endured by a patient” and “no prospect for the patient to get better”. However, even in such a difficult situation, the family request must be supported with the patient’s will to die.

Further analysis with Pearson Chi-square test showed that there were neither gender nor study level differences in attitudes towards issues pertaining to the end-of-life.

The qualitative analysis further confirmed the quantitative findings in terms of general disapproval of any form of euthanasia. Most of the participants believed that euthanasia is taking someone’s life, and this was not ethically good. However, one of the interviewees said she had never heard the term euthanasia so when filling the questionnaire, she searched about it on the internet, and she understood that euthanasia is related to assisting seriously sick people by ending their pain. In this context, she believed euthanasia was acceptable.

Similarly, to the results in the survey, the interviewees were prone to assist the terminally ill patients in ending their life if there was no other way to ease their pain. However, there was an interesting distinction made between “a terminally sick person” and “a terminally sick friend or family member”. While it was considered possible to assist “another person” the interviewees were not inclined to assist a close friend or a family member. One of the interviewees explained: “Seeing my family member or anyone close to me is like seeing myself in this suffering and I wouldn’t kill myself” (female student).

All of the interviewees affirmed that they believe their parents and grandparents “treasured life, they all valued life” (female student). Thus, they would never agree to take another person’s life because someone was sick. One of the male students explained that in his culture, people used to believe that “every person has time to die. So if he or she suffers a lot, let them do their time”.

Discussion

Euthanasia

Our study showed limited knowledge increasing with years of study among health students on topics related to the end-of-life issues such as euthanasia, physician-assisted suicide and therapeutic sedation. This may be connected with the low relevance of these issues in the local cultural context. As pointed by Nongkas & Tivinarlik,29 local beliefs that harmony with deceased ancestors living in the spiritual world is essential to the peace and benefits in life calls for great respect towards the elderly and moves euthanasia to a very distant and irrelevant position. Cultural beliefs and values provide a reference to approach end-of-life issues. One can presume that different cultural and religious values in societies are responsible for large differences in the acceptance of euthanasia. Our findings showing that, generally, the acceptance of euthanasia increases with years of training are in line with similar results from Poland11 and the UK,14 where students in the final year of study were more likely to support various actions related to euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide. Like our study, others reported a higher general acceptance of euthanasia than a willingness to take an active part in ending a patient’s life.37,38

Another factor related to the attitude towards end-of-life issues were religious beliefs. A high religious affinity to one of the Christian churches among our study participants could be an additional factor contributing to a high level of rejection of euthanasia. In this manner, this study complements the findings of numerous studies, which confirm that peoples’ commitment to religious beliefs were less in favor of assisted suicide and euthanasia.5,14,23,37,39 Conversely, gender was not associated with attitudes towards euthanasia and assisted suicide neither in this study nor others.5,13,14,23 The different results were found in Australia, where female doctors were more opposed to euthanasia than their male colleagues.25

Abortion

While our findings reveal a higher acceptance of abortion compared to euthanasia, Musgrave and Soundry,40 in a study conducted among participants of an international midwifery conference, observed a positive relationship between their attitude to abortion and active euthanasia. Though the majority (70%) of health students in our study were opposed to abortion for social reasons; however, they postulated that abortion should be legal in cases of rape (96%), a risk to the woman’s life or health (91%), congenital anomalies (86%), and mental incapacities (63%). Such results correspond with the broader body of knowledge. Similar attitudes were demonstrated by students in Jamaica,9 Brazil,5 Poland.11

Generally, we recorded that the acceptance of abortion for all reasons increased with years of study. Likewise, Agnihotri, Agnihotri and Jeebun41 reported that views of medical students are changing with the year of their study, more year-4compared to year-1 medical students accepted abortion. Another factor influencing agreement for abortion was religious affiliation and values.5,42–44 O’Grady et al45 concluded that religious adherence was the strongest determinant of an Irish medical student’s perspective on the ethics of abortion.

Training in Bioethics

Surprisingly, we found that only a small proportion of students gained their knowledge of bioethical issues from lectures. While teaching of bioethics in health programs is well established in developed countries, in developing countries, bioethics is being introduced only recently to major health programs but needs further development.46 Furthermore, bioethical programs taught in developed countries cannot be just copied to the bioethics programs in developing countries. This is because current ethical issues such as, euthanasia, surrogate motherhood, genes therapy, stem cells and organ transplantation which, are relevant to high-income countries, are not important in most developing countries. Rather than copying bioethical programs from industrialized countries, more appropriate is adapting bioethics discussions to the priority needs of developing countries such as, just distribution of health resources, establishing health priorities and cultural adaptation of policies.47–50 The World Health Organization calls for stronger cross-cultural emphasis in medical training. Training in bioethics should enhance physicians’ ability to navigate culturally sensitive ethical issues and improve the quality of patient care.17,51 In teaching professional ethics, Hicks et al52 pointed out the role of a “hidden curriculum”, in other words, the role of model clinicians providing an example of ethical behavior. Another study emphasized the need for complementing a formal bioethics program by multidisciplinary solving of ethical problems in clinical practice and medical research.53

Conclusion

The study offered a comprehensive description and analysis of PNG students’ knowledge and attitudes towards ethical issues pertaining to the beginning and the end of human life. Students showed a higher acceptance of abortion than euthanasia. More year-4 students presented significantly deeper knowledge of euthanasia and abortion compared to year-1 students. There were no gender differences regarding knowledge and attitude towards these two bioethical issues. The majority of students opposed the idea of women’s right to abortion, which is attributed mainly to socio-cultural reasons. The qualitative analysis indicated a very strong perception that having children “defines” womanhood and also revealed general disapproval of any form of euthanasia. There was a much lower level of acceptance of various forms of active euthanasia compared to the acceptance of abortion. This was suggested to be associated with a respect for older people in Melanesian society and beliefs that ancestors’ support is required for achieving prosperity in life.

Health students presented a low level of knowledge towards bioethical issues, and together with a small proportion gaining their knowledge from lectures and tutorials, this indicated inadequate teaching of bioethics and called for further improvement. In the perspective of rapid social and cultural changes in the Papua New Guinea society, further studies on changing attitudes towards bioethics issues would be valuable.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Hariharan S, Jonnalagadda R, Walrond E, Moseley H. Knowledge, attitudes and practice of healthcare ethics and law among doctors and nurses in Barbados. BMC Med Ethics. 2006;7(1):1–9. doi:10.1186/1472-6939-7-7

2. Ranasinghe AWIP, Fernando B, Sumathipala A, Gunathunga W. Medical ethics: knowledge, attitude and practice among doctors in three teaching hospitals in Sri Lanka. BMC Med Ethics. 2020;21:69. doi:10.1186/s12910-020-00511-4

3. Fillus IC, Rodrigues CFA. Knowledge of medical ethics and bioethics by medical students. Rev Bioética. 2019;27(3):482–489. doi:10.1590/1983-80422019273332

4. Serodio A, Kopelman BI, Bataglia PUR. The promotion of medical students’ moral development: a comparison between a traditional course on bioethics and a course complemented with the Konstanz method of dilemma discussion. Int J Ethics Educ. 2016;1:81–89. doi:10.1007/s40889-016-0009-8

5. Lucchetti G, de Oliveira LR, Leite JR, Lucchetti ALG. Medical students and controversial ethical issues: results from the multicenter study SBRAME. BMC Med Ethics. 2014;15:85. doi:10.1186/1472-6939-15-85

6. Brajenović-Milić B, Ristić S, Kern J, Vuletić S, Ostojić S, Kapović M. The effect of a compulsory curriculum on ethical attitudes of medical students. Coll Antropol. 2000;24(1):47–52.

7. Woloschuk W, Harasym PH, Temple W. Attitude change during medical school: a cohort study. Med Educ. 2004;38:522–534. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2929.2004.01820.x

8. Casini M, Meaney J, Midolo E, Cartolovni A, Sacchini D, Spagnolo AG. Why teach bioethics and human rights to health professions undergraduates? JAHR. 2014;5/2(10):349–368. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004916

9. Matthews G, Atrio J, Fletcher H, Medley N, Walker L, Benfield N. Abortion attitudes, training, and experiences among medical students in Jamaica, West Indies. Contracept Reprod Med. 2020;5(1). doi:10.1186/s40834-020-00106-9

10. Alvargonzález D. Knowledge and attitudes about abortion among undergraduate students. Psicothema. 2017;29(4):520–526. doi:10.7334/psicothema2017.58

11. Korzeniewska-Eksterowicz A, Przysło Ł, Kȩdzierska B, Stolarska M, Młynarski W. The impact of pediatric palliative care education on medical students’ knowledge and attitudes. Sci World J. 2013;2013:1–9. doi:10.1155/2013/498082

12. Wheeler SB, Zullig LL, Reeve BB, Buga GA, Morroni C. Attitudes and intentions regarding abortion provision among medical students in South Africa. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2012;38(3):154–163. doi:10.1363/3815412040

13. Kontaxakis VP, Paplos KG, Havaki-Kontaxaki BJ, et al. Attitudes on euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide among medical students in Athens. Psychiatriki. 2009;20(4):305–311.

14. Pomfret S, Mufti S, Seale C. Medical students and end-of-life decisions: the influence of religion. Future Health J. 2018;5(1):25–29. doi:10.7861/futurehosp.5-1-25

15. Tey NP, Yew S, Low W, et al. Medical students’ attitudes toward abortion education: Malaysian perspective. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):1–7. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052116

16. Bamberger B, Guinan P. What do medical students think about medical ethics? UIC-COM student medical ethics questionnaire. Linacre Q. 2012;79(3):275–281. doi:10.1179/002436312804872703

17. Greenberg RA, Kim C, Stolte H, et al. Developing a bioethics curriculum for medical students from divergent geo-political regions. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:193. doi:10.1186/s12909-016-0711-4

18. Schicktanz S, Raz A, Shalev C. The cultural context of patient’s autonomy and doctor’s duty: passive euthanasia and advance directives in Germany and Israel. Med Health Care Philos. 2010;13(4):363–369. doi:10.1007/s11019-010-9262-3

19. Miyashita M, Hashimoto S, Kawa M, Kojima M. Attitudes towards terminal care among the general population and medical practitioners in Japan. Japan J Public Health. 1999;46(5):391–401.

20. Adhikari S, Paudel K, Aro AR, Adhikari TB, Adhikari B, Mishra SR. Knowledge, attitude and practice of healthcare ethics among resident doctors and ward nurses from a resource poor setting, Nepal. BMC Med Ethics. 2016;17(1):1–8. doi:10.1186/s12910-016-0154-9

21. Siaw LK, Tan SY. How Hawaii’s doctors feel about physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia: an overview. Hawaii Med J. 1996;55(12):296–298.

22. Ahmed AM, Kheir MM, Abdel Rahman A, Ahmed NH, Abdalla ME. Attitudes towards euthanasia and assisted suicide among Sudanese doctors. East Mediterr Health J. 2001;7(3):551–555.

23. Lee W, Price A, Rayner L, Hotopf M. Survey of doctors’ opinions of the legalization of physician assisted suicide. BMC Med Ethics. 2009;10(1). doi:10.1186/1472-6939-10-2

24. Ward BJ, Tate PA. Attitudes among NHS doctors to requests for euthanasia. Br Med J. 1994;308(6940):1332–1334. doi:10.1136/bmj.308.6940.1332

25. Marini MC, Neuenschwander H, Stiefel F. Attitudes toward euthanasia and physician assisted suicide: a survey among medical students, oncology clinicians, and palliative care specialists. Palliat Support Care. 2006;4(3):251–255. doi:10.1017/S1478951506060329

26. Peretti-Watel P, Bendiane MK, Pegliasco H, et al. Doctors’ opinions on euthanasia, end of life care, and doctor-patient communication: telephone survey in France. Br Med J. 2003;327:595. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7415.595

27. Rousseau S, Turner S, Chochinov HM, Enns MW, Sareen J. A national survey of Canadian psychiatrists’ attitude toward medical assistance in death. Can J Psychiatry. 2017;62(11):789–794. doi:10.1177/0706743717711174

28. Onwutaeka-Philipsen B, Fisher S, Cartwright C, et al. End-of-life decision making in Europe and Australia: a physician survey. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:921–929. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.8.921

29. Nongkas C, Tivinarlik A. Melanesian indigenous knowledge and spirituality. Contemp PNG Stud DWU Res J. 2004;1:57–68.

30. Jenkins C. The National Sexual and Reproductive Health Research Team. Papua New Guinea: National study of sexual and reproductive knowledge and behavior; 1994.

31. Asa I, de Costa C, Mola G. A prospective survey of cases of complications of induced abortion presenting to Goroka hospital, Papua New Guinea. ANZJOG. 2012;52(5):491–495. doi:10.1111/j.1479-828X.2012.01452.x

32. McGoldrick AI. Termination of pregnancy in Papua New Guinea: the traditional and contemporary position. PNG Med J. 1981;24(2):113–120.

33. Valley LM, Homiehombo P, Keely-Hanku A, Whittaker A. Unsafe abortion requiring hospital admission in the Eastern Highlands of Papua New Guinea: a descriptive study of women’s health care workers’ experiences. Reprod Health. 2015;12(22). doi:10.1186/s12978-015-0015-x

34. Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research.

35. Sedgwick P. Cluster sampling. BMJ. 2014;348. doi:10.1136/bmj.g1215

36. Khazaal Y, Van Singer M, Chatton A, et al. Does self-selection affect samples’ representativeness in online surveys an investigation in online video game research. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(7):e164. doi:10.2196/jmir.2759

37. Jacobs RK, Hendricks M. Medical students’ perspectives on euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide and their views on legalizing these practices in South Africa. S Afr Med J. 2018;108(6):484–489. doi:10.7196/SAMJ.2018.v108i6.13089

38. Ozcelik H, Tekir O, Samancioglu S, Fadiloglu C, Ozkara E. Nursing students’ approaches toward euthanasia. OMEGA J Death Dying. 2014;69(1):93–103. doi:10.2190/OM.69.1.f

39. Verbakel E, Jaspers E. A competitive study on permissiveness toward euthanasia. Public Opin Q. 2010;74(1):109–139. doi:10.1093/poq/nfp074

40. Musgrave CF, Soudry I. An exploratory pilot study of nurse-midwives’ attitudes toward active euthanasia and abortion. Int J Nurs Stud. 2001;38(4):493–494. doi:10.1016/S0020-7489(01)00027-X

41. Agnihotri AK, Agnihotri S, Jeebun N. Study of medical students’ attitudes towards physician-assisted suicide in Mauritius. Indian J Libr Inf Sci. 2008;1(1):21–23.

42. Freeman E, Coast E. Conscientious objection to abortion: Zambian healthcare practitioners’ beliefs and practices. Soc Sci Med. 2019;221:106–114. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.12.018

43. Gleeson R, Forde E, Bates E, Powell S, Eadon-Jones E, Draper H. Medical students’ attitudes towards abortion: a UK study. J Med Ethics. 2008;34(11):783–787. doi:10.1186/s12909-016-0711-4

44. Steele R. Medical students’ attitudes to abortion: a comparison between Queen’s University Belfast and the University of Oslo. J Med Ethics. 2009;35(6):390–394. doi:10.1136/jme.2008.026344

45. O’Grady K, Doran K, O’Tuathaigh CMP. Attitudes towards abortion in graduate and non-graduate entrants to medical school in Ireland. Br Med J. 2016;42:201–207. doi:10.1136/jfprhc-2015-101244

46. Ogundiran TO. Enhancing the African bioethics initiative. BMC Med Educ. 2004;4(1). doi:10.1186/1472-6920-4-21

47. Barchi F, Singleton KM, Magama M, Shaibu S. Building locally relevant ethics curricula for nursing education in Botswana. Int Nurs Rev. 2014;61(4):491–498. doi:10.1111/inr.12138

48. Olweny C. Bioethics in developing countries: ethics of scarcity and sacrifice. J Med Ethics. 1994;20:169–174. doi:10.1136/jme.20.3.169

49. Raja AJ, Wikler D. Bioethics in developing countries. J Health Popul Nutr. 2001;19(1):4–5.

50. UNESCO. Asia Pacific Perspectives on Bioethics Education. In: Calderbank D, Macer DRJ, eds. Bangkok: UNESCO; 2008.

51. Nelson WA, Gardent PB, Shulman E, Splaine ME. Preventing ethics conflicts and improving healthcare quality through system redesign. BMJ Qual Saf. 2010;19(6):526–530. doi:10.1136/qshc.2009.038943

52. Hicks LK, Robertson DW, Robinson DL, Woodrow SI. Understanding the clinical dilemmas that shape medical students’ ethical development: questionnaire survey and focus group study. Br Med J. 2001;322:709–710. doi:10.1136/bmj.322.7288.709

53. Mohammad M, Ahmad F, Rahman SZ, Gupta V, Salman T. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of bioethics among doctors in a tertiary care government teaching hospital in India. J Clin Res Bioeth. 2011;2:118. doi:10.4172/2155-9627.1000118

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.